Thatch

Curing American healthcare through incentives and choice

Welcome to the 2,123 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 251,962 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Wednesday! Since our last essay, we crossed the quarter-million subscriber mark. A huge thanks to all of you for reading Not Boring.

Today’s Deep Dive is a long time in the making.

Since Not Boring Capital invested in Thatch in early 2022, I have been talking to the company’s founders, Chris and Adam, about doing a Deep Dive when the time was right.

The time is right now.

For the first time since World War II, America has a real shot at fixing its healthcare system. A 2020 regulation called ICHRA lets employers give employees tax-free dollars to spend on whatever insurance plan and healthcare services work best for them.

It sounds small, a quirk in the tax code. But little tax code quirks are how we got into this mess (WWII wage freezes leading to employer insurance), and how we got out of a similar one (401(k)s replacing pensions). And as we speak, legislation is being introduced that would make ICHRA permanent under a new name, CHOICE, and provide businesses with a $1,200 per employee tax credit for offering it.

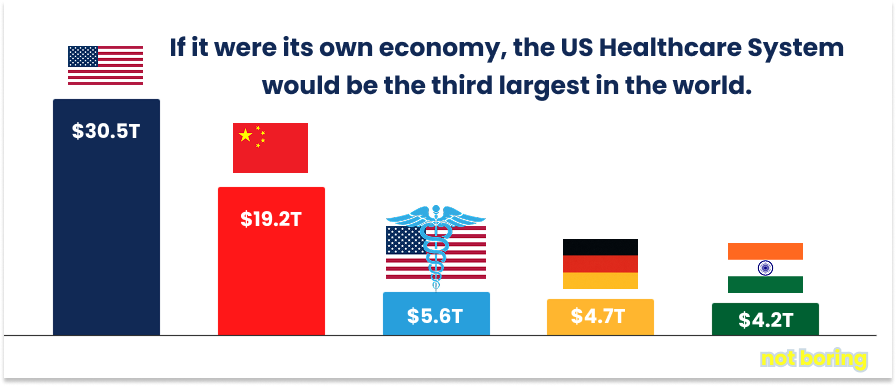

ICHRA can decouple insurance from employment, give people control over their health, and unleash free markets on a $5.6 trillion system.

Thatch builds infrastructure to make ICHRA work. Because of how insurance works, the more members Thatch covers, the better and cheaper the plans become. With enough scale, Thatch can help decouple insurance from employment, align incentives towards long-term health, and bring down costs.

Which means that you can help fix American health insurance by considering Thatch for your business.

American healthcare seems hopelessly broken. It’s not. Thatch can help fix it.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Silicon Valley Bank

SVB’s new State of the Markets H2 2025 report highlights a complex and uneven recovery across the innovation economy. While some sectors are experiencing renewed growth, others face persistent challenges with stagnant deal activity, depressed valuations and limited exits.

Startups that raised capital last year did so with tight financial discipline — but runway is still a concern with 50% of VC-backed tech companies having less than a year of cash remaining.

Download the report today for a deeper understanding of these trends and gain strategic insights for navigating the second half of the year.

Thatch

In May, I was catching up with Chris Ellis and Adam Stevenson, the founders of Thatch, when they told me a story.

Chris and Adam had recently spoken to someone at a health insurer about whether they’d offer things like Prenuvo screens that might catch cancer and improve outcomes (at lower cost).

They wouldn’t, the insurer said.

“If I catch that person’s cancer,” he explained, “They’ll leave their job in 2.5 years and go to a competitor insurer.”

In other words, the insurance provider that someone gets through their job isn’t incentivized to save that person’s life because that person might switch jobs, and if they do, the initial insurer is left holding the bag on the treatment cost while the next insurer reaps the benefit of covering a now-healthy member. The numbers say the insurer just needs to let the cancer odds ride.

That should make you angry. Because you’re probably insured by one of these insurers, too.

This is one of the many, many things that should make you angry about, and embarrassed by, the American healthcare system. It’s bad enough that it’s expensive, but after all that money, your life is not their top priority!

But who do you get mad at?

The insurer is just doing their job. If they loosen things up, they either lose money and go out of business, or everyone’s health insurance premiums go up.

The employer is doing their job, too. They’re just offering health insurance to attract and retain the very best people. If they don’t, how could they possibly compete in the talent marketplace?

Run through this exercise with each of the players involved, and you end up mad at a system, tilting at windmills.

So how do you change a whole system?

“Show me the incentives,” Charlie Munger said, “and I’ll show you the outcome.”

The American healthcare system is a layer-cake of misaligned incentives so complex that attempts to fix it by changing one thing here or another there often make things worse. It is the rare non-socialist system (the only one in the OECD that doesn’t guarantee health coverage to its citizens) that makes you think the socialists may be on to something, after all.

At least, when the government is responsible for healthcare, there is one payer, which reduces administrative burden (America pays 7.6% of healthcare costs on administration vs. a 3.8% OECD average) and, more importantly, aligns incentives. If a Swedish person gets cancer at any point in her life, the Swedish government is on the hook, regardless of which company she happens to be working for when the bad news comes.

The original sin of American health insurance is that our insurance is tied to our employer. America is the only developed nation in which:

Your employer chooses your insurer.

You lose that insurer when you leave your job.

Private insurers make coverage decisions based on expected customer lifetime value.

That lifetime value is artificially capped at ~2.5 years (average job tenure).

As constructed, the American system manages to combine the worst aspects of market-based and employment-based systems while capturing the benefits of neither. In fact, it mixes in the worst aspects of socialist healthcare, too: because many chronic conditions get really costly as people age, taxpayers often foot the bill for the private insurers’ short-termism via Medicare.

That we are in this mess is an accident of history, a corporate response to World War II-era incentives that froze wages and tax-advantaged defined benefits, that has been codified and coagulated into an increasingly sticky mess over the intervening seven decades. The misaligned incentives in health insurance compound, and are compounded by, everything else broken in American healthcare, from pharmaceutical pricing to hospital consolidation to what we eat.

The way out of this mess is the same way America finds its way out of any mess too complex for top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions: by using new regulation to unleash the twin powers of free market capitalism and American consumer choice.

That is how we replaced pensions with 401(k)s.

That is what Chris and Adam built Thatch to do for healthcare.

Thatch is rewiring the incentives in the American healthcare system by giving individuals choice under the Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement (ICHRA).

Through ICHRA, employers can offer their employees a defined contribution, or allowance, towards healthcare each year, tax-free. With those dollars, employees can choose their own individual insurance plans, which they can keep even after they switch jobs, and spend on any health-related expense that they believe is best for them and their family.

ICHRA has all sorts of implications.

Employers are no longer stuck with group plans (the longstanding existing system in which employers choose a single plan for all of their employees) whose premiums continue to skyrocket because no one is incentivized to see them come down. In 2005, it cost $12,214 to insure a family of four in a typical employee-sponsored health plan. Today, it costs $35,119. That 6.1% annual growth has far outpaced inflation, even while contributing to it. Over the past 20 years, wages in America have grown 84%; healthcare costs have grown 188%.

Healthcare’s ridiculously high costs are bad because they’re directly high, but also because they keep people stuck in safe jobs that offer good benefits instead of starting new businesses or pursuing their passions. The opportunity costs extracted by healthcare don’t show up in the numbers, but they’re high, too.

With ICHRA, employees can now choose their own plans, no longer saddled with the lowest common denominator option. They can pick the one that works best for them and their family. And they can pick the job that works best for them and their family.

They can also choose to spend their allowance on the things that they believe will improve their health, save their lives, and even bring new life into the world, things like cancer screenings, Function diagnostics, Oura rings, therapy, TrueMed, Eight Sleep mattresses, or IVF. Many of these are currently inaccessible to virtually all Americans due to their cost.

And by giving employees the ability to choose individual plans, they also give them the chance to bring their plans with them from job to job, and even when they’re between jobs. Your insurance is no longer tied to your job, and you can keep the same insurer for decades, assuming they do a good job for you. All of a sudden, that insurer is incentivized to make sure that you stay healthy: you’ll pay them for longer, and if you catch something like cancer early, it will cost them a lot less to fix it now than to pay for less effective and more expensive treatments later.

When I spoke to Chris and Adam in May, it was the day after I’d written Everything is Technology, one of the main points of which was that technology companies can replace seemingly permanent institutions surprisingly quickly. Humans used horses to get around for thousands of years, then boom, Model T, and within a decade, New York’s streets were horseless.

So Chris and Adam were excited: this was exactly how they thought about the healthcare system, they told me.

Healthcare in America seems hopelessly broken. It’s not. Nothing is.

Thatch’s mission is “to build a healthcare system people love.”

And you know what? I think they just might pull it off.

There is no team better equipped to bring ICHRA to the people. While the program has a ton of potential, it’s also hard for companies to administer and for employees to use. Without good products, more choice can just mean more mess.

Employers are required to define budgets, handle reimbursements, ensure regulatory compliance, manage payroll, provide guidance to employees, and juggle countless other details. Employees need to obtain coverage themselves, submit reimbursements, and manage their own budget themselves. Freedom isn’t free.

What Chris and Adam realized, though, is that “the hardest parts of making ICHRA work are primarily fintech problems: managing budgets, issuing funds, remitting and tracking payments, handling adjudication.”

So Chris, an MIT cancer researcher turned biotech salesperson, and Adam, a former founder and early Stripe employee, brought together a team of top performers from Stripe, Ramp, Rippling, and even the former CEO of UnitedHealthcare Pacific Northwest, to build the financial and operational infrastructure necessary to abstract away ICHRA’s complexity.

It’s early, but it’s working.

Since I invested in the a16z-led Seed round in 2022, Thatch raised a $38 million Series A in July 2024 and a $40 million Series B in March 2025. Both rounds were led by Index Ventures, with participation from a16z and General Catalyst (which bought an entire healthcare system in 2024).

“When a reputable venture firm leads two consecutive rounds of investment in a company,” Andreessen told me [Tad Friend, for an excellent 2015 New Yorker Profile, Tomorrow’s Advance Man], “Thiel believes that that is ‘a screaming buy signal,’ and the bigger the markup on the last round the more undervalued the company is.”

Jahanvi Sardana, the Index Ventures Partner who led both of the firm’s investments in Thatch, told me that for Index to lead the Series A and Series B for the same company so quickly has only happened once in the firm’s history. “Wiz was the only other one,” she said, referring to the five-year-old cybersecurity company that Google recently bought for $32 billion in cash.

Thatch grew revenue 8x last year. It’s on pace to 4x again this year, conservatively.

That number may be very conservative if the government passes standalone CHOICE bills, which look to be coming in the Senate and the House, that would give employers a $1,200 per employee tax credit to implement ICHRA, or as the proposed bill rebrands it, CHOICE. A separate bill, the Small Business Health Options Awareness Act of 2025, was introduced last week to require the Small Business Administration (SBA) to provide more outreach and education on ICHRA to small businesses. Gary Daniels, the former UHC Pacific Northwest CEO who is now the Chief Growth Officer at Thatch, told me that if passed, CHOICE “will kill small business group insurance. The entire industry will have to rotate into it.”

All of which means that Thatch really does have the opportunity to elevate US healthcare, by giving individuals control over their own healthcare spending, saving businesses money, and aligning insurer incentives.

Like products with network effects, systems tied together by a certain set of incentives are incredibly hard to change, until they’re not. As network effects and incentives unwind, they fall with speed proportional to their original strength.

Because of how insurance works, as people switch from group to individual plans, group plans get more expensive and individual plans get less expensive, which causes more people to switch, which accelerates the vicious (from the perspective of the incumbents) or virtuous (from the perspective of all of the rest of us) cycle.

In this Deep Dive, we’ll cover exactly how this mechanism works by talking about how the healthcare system currently works, how we got here, how it’s starting to change, and what Thatch is building to accelerate the change. Then we’ll imagine a world with better healthcare.

There is no law of physics that says that American healthcare needs to suck. So eventually, it won’t. Thatch is pulling eventually forward.

The Thatch Thesis

We are going to dive into a dizzying amount of detail about the American healthcare system. As we do, it’s helpful to keep the Thatch thesis in mind. Here’s how I think about it.

The Thatch thesis is that free markets with aligned incentives can, over time, fix healthcare, and that by providing the infrastructure to make free healthcare markets work, Thatch can unlock and capture a tremendous amount of value.

Currently, 154 million Americans are covered by employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) under plans that cost $1.3 trillion annually. These employer-linked plans are typically not ideal for employers (costs increasing and unpredictable), employees (not personalized, can’t take it with them), or the system (no one is incentivized for long-term health).

ICHRA has the potential to fix many of the issues with health insurance today.

For employers, it is a defined contribution and can offer better perks to employees while saving money.

For employees, they can choose the plan that best suits their and their families’ needs, and spend on the things that matter to them; a young person who never goes to the doctor might choose a low-cost plan and spend the balance through Thatch’s marketplace.

For the system, it incentivizes insurers to optimize for long-term health, and introduces free market competition.

That last point on competition is crucial. As ICHRA membership scales, insurers (carriers) will offer increasingly tailored plans and compete in the marketplace. While ESI plans are full of bloat - Mario Schlosser, Oscar’s co-founder and President of Technology, told me that in large employer markets, vendors will charge $8 per member per month (PMPM) just for monthly billing, and multiple dollars PMPM to maintain the plan’s mobile app - in the individual market, every cent PMPM matters. And because employees will have excess healthcare budget to spend, their dollars can go to a growing number of consumer health startups who can build better individualized products.

But ICHRA is too complex for almost any business or employee to manage on their own. For it to succeed, it needs a product like Thatch.

Thatch makes ICHRA simple.

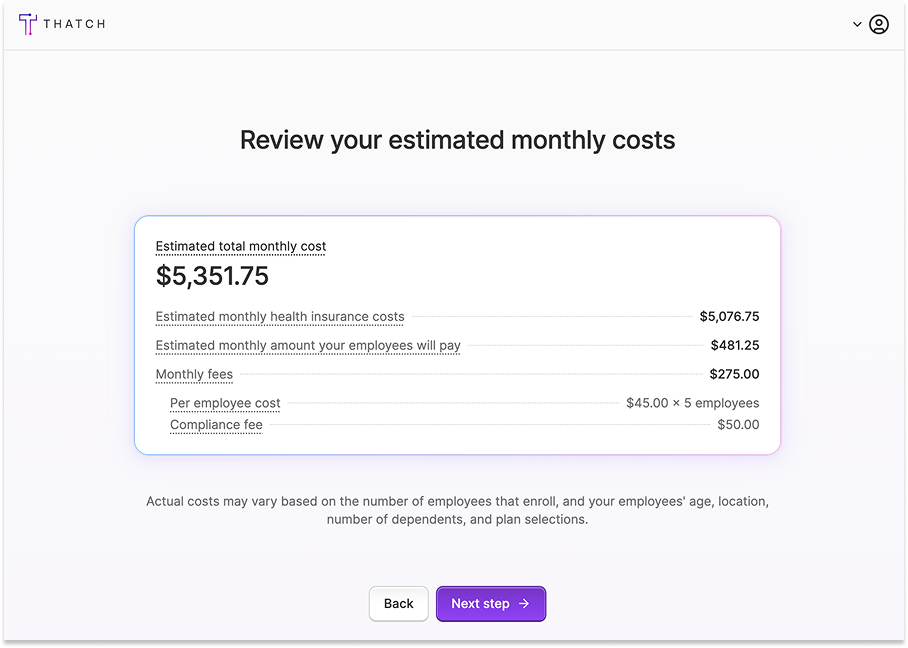

Before even signing up, employers can enter some information about their employees to understand potential costs and coverage. Employers connect their payroll and set a healthcare budget. Employees get a Thatch card and choose any health insurance plan they want, and can spend remaining funds on health services from glasses to therapy to scans in Thatch’s Marketplace. Thatch handles all the compliance, payments, reimbursements, and complexity that made ICHRA impossible for most companies to implement themselves. It’s extremely complex under the hood so that it can be incredibly simple for users.

By handling all of the financial and operational complexity of ICHRA – compliance, payroll, payments, plan selection, marketplace, and more – with modern software and products, Thatch can both accelerate ICHRA adoption and make money in a number of different ways.

Thatch can monetize through subscriptions, interchange, commissions, and a marketplace take rate. They do well if the ecosystem does well.

“Thatch’s is a win-win-win business model that’s hard to find,” Julie Yoo, the a16z Partner who led the firm’s investments in Thatch, explained. “Usually in healthcare, business models are: you get screwed on multiple fronts and eke out one way to make money. Thatch uniquely benefits from everyone else doing well.”

It is a situation well-suited for Thatch’s founders, who are as nice as any founder this side of Ramp’s Eric Glyman. “I like to back mama’s boys, like Chris,” Jahanvi joked, seriously. “The fact that you care about somebody more than you care about yourself is a good indicator because you have to care about your company more than yourself.”

Chris and Adam are two people you want to see win. They bonded over the shared tragedy of losing parents to cancer, decided to build a company to enable precision medicine for every cancer patient by helping them access precision oncology trials, and realized, because of the way the incentives work, that if you really want to cure cancer, and fix American healthcare more broadly, you’ve got to fix the incentives first.

So that is what they are doing. They are two people you want to see win building a company that America needs to see win.

And you can help Thatch win, and help fix American healthcare, by winning for your employees. With Open Enrollment coming up, I would encourage you to check out Thatch for your business.

The more members in the individual market, the better the plans get. If it reaches escape velocity, ICHRA could be the rare healthcare experience that gets better and cheaper with time.

ICHRA is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to change the way healthcare works in America.

Jonathan Swerdlin, the founder of Function Health, was clear about what’s happening: “This is where the world is going, and everything is going to bend towards it. The transformation is happening in politics, tech, and culture. Now, people are getting the opportunity to make better decisions for themselves. It is not a trend. It’s an evolution.”

What might stop the evolution, I asked. “Nothing man. Fucking nothing. Nothing’s going to stop this.”

So this is the story of the evolution of healthcare in America, and how you build a company to accelerate something that, once started, fucking nothing can stop.

A Brief History of Health Insurance (and Defined Benefits)

To understand how we get out of this mess, we need to understand how we got into it in the first place.

“It was started 80 years ago as a result of soldiers and personnel coming back from war,” former Aetna and current Oscar Health CEO Mark Bertolini told Patrick O’Shaughnessy on a recent episode of Invest Like the Best.

What had happened was, Congress passed the Stabilization Act in 1942, giving the President the authority to freeze wages and salaries to combat inflation during World War II. Franklin Delano Roosevelt invoked these new powers the very next day with an Executive Order which applied to “all forms of direct or indirect remuneration to an employee,” including but not limited to salaries and wages, as well as “bonuses, additional compensation, gifts, commissions, fees, and any other remuneration in any form or medium whatsoever.”

FDR then slipped in what may be the most consequential parenthetical in history: “(excluding insurance and pension benefits in a reasonable amount as determined by the Director).”

Employer-sponsored insurance found itself in the right place at the right time. It was a relatively new phenomenon. In 1883, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced the world’s first system of employer-based insurance. German employers and employees contributed to sickness funds that in turn pay for employees’ healthcare needs from state-run or private providers. This came to be known as the Bismarck Model.

In 1948, Lord Beveridge established the first system in which the government provided health care for all its citizens through tax payments. In the Beveridge Model, many of the hospitals and providers themselves are government owned and operated.

With the introduction of the Beveridge Model, nearly every Bismarck system became universal, meaning that even with private insurance and providers in place, the government supported those who couldn’t pay through taxation.

Today, nearly every developed country uses some version of Bismarck (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Czech Republic, South Korea, Netherlands), Beveridge (UK, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, New Zealand), or a hybrid of the two (France, Hungary, Slovakia).

I say “nearly,” because that is not how it works in the United States.

The desire to pool risk in order to avoid catastrophic ruin seems to be fundamental. In the same year (1787) and in the same city (Philadelphia) that the Constitutional Convention met to draft the U.S. Constitution, two African American ministers, founded The Free African Society, America’s first mutual aid society, to provide burial assistance, support for widows and orphans, care for the sick, financial assistance during hardship, and moral and social support to freed slaves in the city.

The concept spread. By 1920, one in three American men belonged to fraternal societies that, among other things, provided “cradle to grave” benefits including medical care, sick pay, and burial insurance for approximately one day’s wages annually.

Around the same time, hospitals were modernizing. No longer simply charity-supported “shelters for the sick poor,” in order to make the capital and operating investments necessary to provide modern services such as surgery and medical laboratories, hospitals began relying on charges instead of charity. This created a problem: many patients were unable to pay, which meant many hospitals were unable to collect.

This seemed to be a challenge perfectly suited to insurance. Insurers in America were already charging premiums to protect against risks they could calculate, like fires, hurricanes, and even loss of income due to illness. They couldn’t, however, figure out how to underwrite medical expenses. The issue was that medical expenses lie within the control of the insured; those with insurance could choose to buy more, and more costly, medical care on the pool’s dime. This “moral hazard” kept insurers away from health insurance.

Insurers weren’t incentivized to take on that risk, but hospitals were. They were the ones stuck footing the bad debt created by patients’ inability to pay.

So in 1929, at Baylor University in Texas, executive vice president Justin Ford Kimball combed through data from a successful sick pay fund he’d established for teachers a decade earlier to determine how he might solve the health insurance problem. He saw that teachers in the plan used, on average, about 15 cents per month on hospitalizations. “With hospitalizations on the rise,” writes Helen Jerman, “Kimball decided to assume that teachers would use triple that amount; then, to be safe, he rounded up, to 50 cents per month.” In exchange for that monthly premium, teachers got access to 21 days of hospital care at Baylor Hospital.

Within months, 75% of Dallas teachers enrolled in the plan that would become the basis of a nationwide network of “Blue Cross” plans. By 1940, six million Americans had joined Blue Cross plans, laying the foundation for private insurance in America.

Although the insurance was private, the American Medical Association fought it as “socialized medicine,” fearing a loss of autonomy over fees. As the plans spread anyway, doctors created their own “Blue Shield” plans, starting with the California Physicians Service in 1939.

FDR entered the White House in the midst of the birth of private health insurance in the US, and of the Great Depression. Not one to shirk from having his government pay for things, FDR entertained the idea of nationalizing healthcare as part of his plan for Social Security, but didn’t pursue it. The AMA would have had a strong case that this really was “socialized medicine” and could have tanked Social Security with their opposition.

This, then, was the state of the health insurance landscape when America entered World War II. Health insurance was growing, paid for by individuals, not employers or the government.

Then, FDR froze wages but not benefits.

Follow the incentives. No longer able to compete for talent on wages, companies competed by offering pensions and health benefits.

An EO is just an EO, but in 1943, the IRS codified it by ruling that employees didn’t owe taxes on employer-provided pensions and health benefits, amplifying this incentive at a time when taxes on corporate profits reached 80-90%.

By 1946, 30% of Americans had health coverage, compared to just 9.6% in 1940. By 1950, 9.8 million Americans received company pensions, up from just 4 million in 1940.

The postwar period cemented this accidental system through deliberate policy choices. The 1954 Internal Revenue Code formally codified the tax exemption for employer health contributions, making them fully deductible for businesses while excluding them from employees’ taxable income, creating a permanent tax subsidy that now costs over $300 billion annually.

By 1958, the year my mom was born, approximately 75% of the 123 million Americans with private coverage obtained it through employment, establishing a pernicious path dependency that we are stuck in to this day.

A lot has happened since 1958, but mostly all within this employer-first path. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the compromise that was Medicare and Medicaid into existence, combining Democratic proposals for hospital insurance (Medicare Part A), Republican proposals for voluntary physician insurance (Medicare Part B), and expanded state programs for the poor (Medicaid). Facing growing healthcare inflation in the 1970s, President Richard Nixon signed the HMO Act of 1973, requiring employers to offer health maintenance organizations (HMOs), with smaller, more restricted provider networks, if available locally.

The “managed care” revolution actually kind of worked, at least financially: HMO enrollment grew from 9.1 million people in 1980 to 58.2 million in 1995, and between 1993 and 2000, healthcare’s share of personal consumption actually declined, from 14.6% to 13.6%.

But as the old adages go, “you get what you pay for” and “there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.” HMOs were cheaper because they offered a worse product. The focus on cost led to headline-making atrocities like “drive-through deliveries” in which women were sent home 24 hours after giving birth, cancer patients being denied experimental treatments, and people literally dying while waiting for out-of-network referrals.

In a booming, labor-tight economy, employees demanded choice, and they got it.

Employers began offering Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs), which allow members to use out-of-network providers by paying more out of pocket, as a recruiting weapon. PPOs grew from just 11% of plans in 1988 to become the dominant model by the early 2010s.

Predictably, however, with PPOs, healthcare inflation resumed its upward march. Employer premiums, which had been growing ~3% per year in the 1990s, grew 10-15% per year in the 2000s. And now, as we’ve learned and as you are probably painfully aware, it costs an average of $35,119 to insure a family of four.

So are we just stuck with the consequences of a situation-specific decision made in the midst of the largest war in human history? Are employees just doomed to suboptimal coverage and employers to ever-increasing costs forever?

I don’t think so, and I planted a little seed earlier that we’ll now water a bit.

Recall that in response to Executive Order 9250, employers began offering health insurance and pensions.

Does your employer still provide you with a pension today?

From Defined Benefit to Defined Contribution

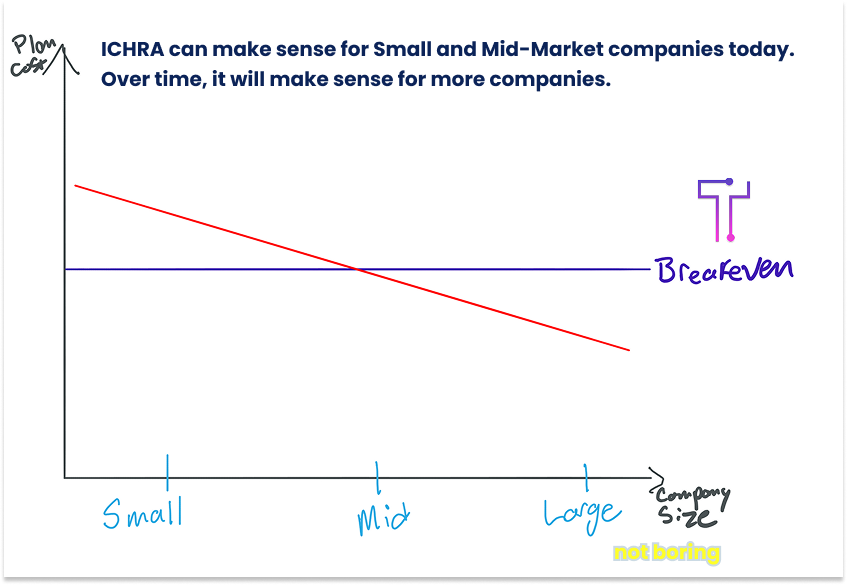

If you wanted to summarize the bull case for ICHRA, and for Thatch, in one chart, it would be this:

Just as World War II era decisions led to the rise of employee sponsored insurance, which offered defined benefits, those same decisions kickstarted the growth of defined benefit pension plans. Employers couldn’t offer wage or salary increases, but they could offer pensions with defined benefits tax-free.

And they did. Between 1945 and 1975, the amount of assets in defined benefits pension plans grew nearly twelve-fold, from $20 billion at the end of the War to $235 billion three decades later.

Under defined benefit pensions, employers guarantee workers a specific monthly payment in retirement, typically based on salary or wage and years of service to the company. The employer is responsible for investing enough, tax-free, to meet the obligations to their employees regardless of market performance or how long the retiree lives. The employer bears all of the investment risk and must make up any shortfalls from their balance sheet if the fund’s assets can’t cover the promised, or defined, benefits.

In retrospect, that’s an insane promise to have made, and predictably, companies came to struggle under the weight of their pension plans.

By the 1970s and 1980s, a bunch of factors combined to make defined benefit pensions unsustainable for employers, including:

People Lived Longer: In 1945, an American expected to live until they were 65. By 1975, that had increased to 72.5, and by 1985 to 74.7. Each extra year of life, while a blessing, meant another unexpected year that the company had to meet its monthly payments.

Markets Got More Volatile: The Oil Crisis, stagflation, and market crashes of the 1970s left companies exposed. The 29.7% decline in the S&P 500 was the largest annual drop since before America entered World War II. Despite weak returns and high inflation, employers still owed their retired employees what they’d promised.

Competition from Unburdened New Entrants: This difficulty was compounded by the fact that incumbents with decades’ worth of pension liabilities faced competition from new entrants who were free of that drag. In the late 1970s, Chrysler and Bethlehem Steel, among many others, cited pension costs as a key reason they struggled against foreign competition.

New FASB Rules Brought Things to a Head: Still, many companies could hide their liabilities and worry only about what they had to pay out each month. In 1985, however, new FASB rules required companies to show pension liabilities on their balance sheets, exposing massive unfunded liabilities to investors.

By happy accident, however, the government accidentally buried a solution in the Revenue Act of 1978. Section 401(k) was a tiny provision hidden deep in the Act meant to solve a specific technical problem with executive bonus deferrals:

“A profit-sharing or stock bonus plan shall not be considered as not satisfying the requirements of subsection (a) merely because the plan includes a qualified cash or deferred arrangement.”

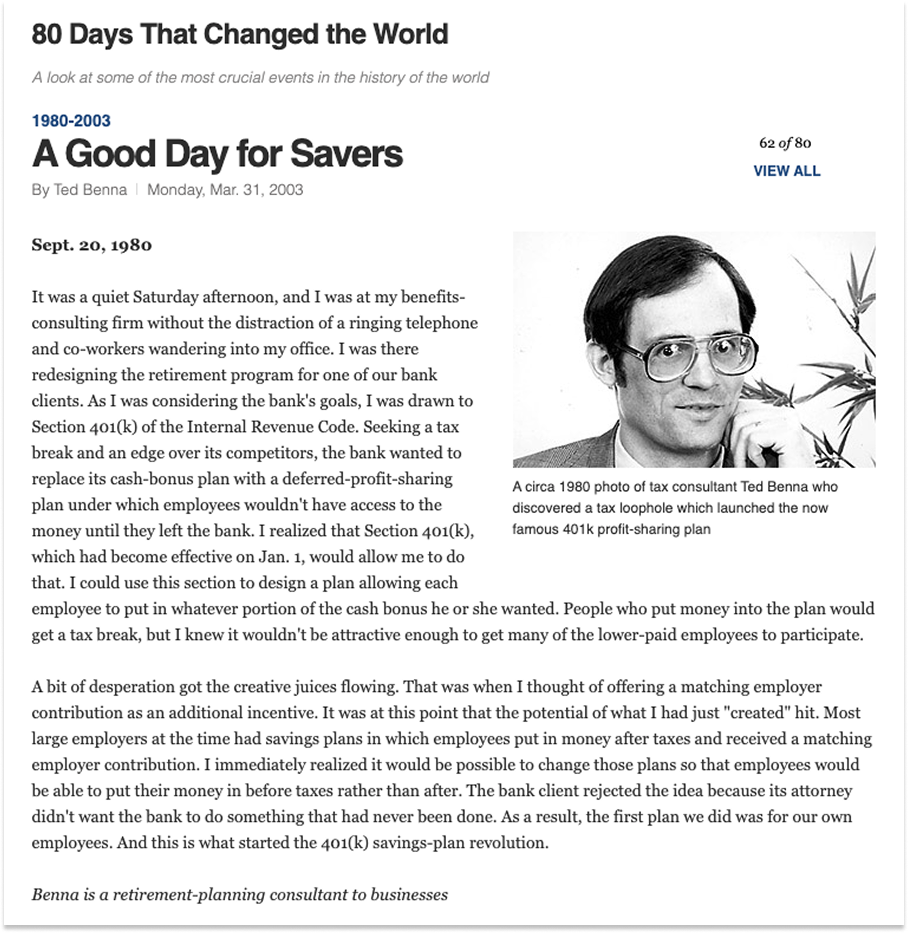

The magic was in what the language didn’t say - it didn’t limit it to executives, didn’t cap contribution amounts aggressively, and didn’t prevent employer matching - omissions upon which a benefits consultant in Pennsylvania named Ted Benna seized on one of what TIME Magazine would call one of the “80 Days That Changed the World.”

Benna’s plan combined employee salary deferrals, employer matching contributions, and existing rules for profit-sharing plans to create something in which ordinary workers and executives alike could save pre-tax dollars with an employee match.

The IRS approved Benna’s interpretation in 1981 and ignited a firestorm in retirement savings. Companies quickly realized that 401(k)s solved a number of problems in one fell swoop:

Employees got an immediate tax deduction instead of having to wait as they did with pensions, and gained control over their investment decisions.

Employers got predictable costs and no long-term liabilities.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle loved it. Republicans liked individual ownership and Democrats liked expanding retirement coverage.

In just two years from the IRS interpretation, by 1983, nearly half of all large firms in the US offered 401(k)s. By 1995, they had accumulated more assets than traditional private pensions. Today, “Americans held $13.0 trillion in all employer-based DC retirement plans on June 30, 2025, of which $9.3 trillion was held in 401(k) plans.”

As it stands, more than three-quarters of private retirement assets are held in defined contribution plans, and the share is growing rapidly. Most defined benefits assets are legacy dollars in legacy plans. Today, over 90% of private retirement plan dollars go to direct contributions, and my hunch is the 10% going to defined benefits are part of plans that legacy companies are unable to get rid of. Your startup doesn’t offer a pension.

So why, in a Deep Dive on healthcare, did I just spend 850 words on 401(k)s? Why is all of the above bullish for ICHRA and Thatch?

ICHRA has the potential to do to employer-sponsored healthcare what 401(k) did to employer-funded retirement savings.

This is not a reach.

Exactly two trillion-dollar accidents emerged from the Stabilization Act of 1942: employer-sponsored defined benefit pensions and employer-sponsored defined benefits insurance.

Both grew dramatically.

Both caused very similar problems.

The problems created by defined benefits retirement plans were solved by the free market response to an initially-underappreciated 1978 regulation that shifted the industry to defined contribution.

The problems created by the other remain both unsolved and critically important to solve; an underappreciated 2019 regulation that incentivizes defined contribution may hold the key.

Healthcare is complex, but it is not uniquely complex. Markets are mind-numbingly complex as well.

From the perspective of a person living in 1975, the unfunded liabilities problem likely seemed almost impossibly hard to solve. You can’t simply make returns better by wishing that they were so. And how do you solve the complex coordination problem among employers, employees, and even unions around retirement benefits? Your company just stops offering pensions. Great. Guess what. You lose your employees to a company that does. There is no top-down solution.

But markets, ignited by regulation, can work. Show it the incentives, and the market will get to work creating the inevitable outcome.

So while healthcare seems unfixable today, there is precedent. And if the flint that started the 401(k) fire was Section 401(k) of the Revenue Act of 1978, the flint that will start the right-sizing of healthcare may be the Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement.

Introducing ICHRA

An Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement (ICHRA) is a defined contribution health benefit. Employers give employees a tax-free allowance to spend on a health plan of their choosing from the individual market.

An ICHRA is the 401(k) of healthcare. It’s a clear, predictable contribution from the employer with total choice and ownership on the part of the employee. Instead of employers choosing plans that kind of work for their average employee, they just fund the ability for each employee to choose what works best for them.

That might mean using the full allowance on a low-deductible Platinum plan if you’re older or expect to have kids that year, or it might mean getting a high-deductible Bronze plan and spending the balance on qualified medical expenses, anything from glasses to LASIK to therapy, if you’re young and healthy.

ICHRAs, done right, seem like the Holy Grail of health insurance. So what, I asked Bruce Johnson, Thatch’s Head of Policy, took them so long?

“We didn’t even have an individual market that was affordable until the ACA (Affordable Care Act) in 2010,” he told me. “In the scheme of policy, and in the face of 80 years of doing things one way - group plans - ICHRA came very fast.”

While HRAs (Health Reimbursement Accounts), which let employers set up a tax-advantaged arrangement to reimburse employees for qualified medical expenses and health insurance premiums, have been around since an IRS ruling formalized them in 2002, no one really used them. In the beginning, employees didn’t have many good options to spend their HRA dollars on: the individual health insurance marketplace in most states was a mess, and the plans that were offered had all sorts of issues. Insurers could deny coverage or charge exorbitant premiums based on a person’s pre-existing conditions. There was no guarantee of coverage, and plans often had limited benefits.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 both set out to create a robust individual marketplace and effectively killed HRAs.

The ACA did create an individual insurance marketplace with new rules that prohibited pre-existing condition discrimination, standardized benefits, and offered subsidies, delivered through a shiny new website (remember the Healthcare.gov debacle)?

At the same time, its market reforms required all health plans to cover a list of “essential health benefits” and prohibited annual dollar limits on those benefits. HRAs, by their very design, have annual dollar limits (the fixed amount the employer contributes). This put standalone HRAs in direct violation of ACA regulations. As a result, most HRAs had to be “integrated” with a traditional group health plan, meaning they could only be used for out-of-pocket expenses like copays and deductibles, not for paying for an individual health plan. This took away their primary advantage as an alternative to traditional employer-sponsored insurance.

In response to these limitations, the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 created the Qualified Small Employer HRA (QSEHRA), a limited form of HRA specifically for small businesses. It was a step in the right direction, but with significant limitations. It was only for small businesses, and came with an annual contribution cap. Uptake, therefore, was limited.

But the idea was good, and it was one that found rare bipartisan support.

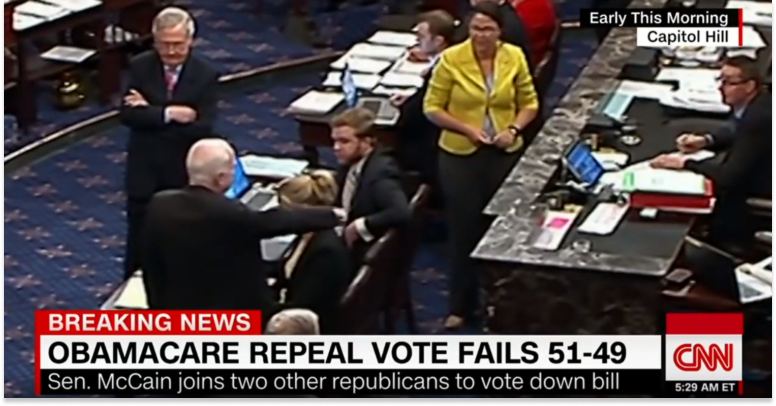

That is a minor miracle. Almost as soon as he entered office, President Trump set to work trying to “repeal and replace” the ACA. That effort failed when John McCain gave it the thumbs down, while Mitch McConnell looked on, shell-shocked.

With repeal off the table, the Trump administration worked to weaken the ACA. It removed the individual mandate penalty in the 2017 tax bill. It shortened open enrollment periods and slashed marketing budgets for ACA marketplaces.

But later that year, that same administration began the process that led to ICHRA, which fundamentally depends on and strengthens the individual insurance markets that the ACA created.

In October 2017, Trump issued Executive Order 13813, Promoting Healthcare Choice and Competition Across the United States, instructing the Secretaries of Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services, to develop regulation that would expand the use and availability of HRAs. By October of 2018, they proposed regulation to allow two new types of HRAs:

Excepted Benefit HRA: Employers can contribute up to $1,800 in conjunction with group plans to cover out-of-pocket costs and certain premiums.

HRAs Integrated with Individual Insurance Coverage: This is what would become ICHRA.

The HRA rule was finalized in June 2019, including both the EBHRA and the newly named ICHRA, which went into effect on January 1, 2020.

The timing seemed catastrophic, at the time.

Just weeks later, COVID-19 shut the world down. Employers laid off millions of employees; it was so bad out there that one of my first Not Boring essays, Schumpeter’s Gale, was an attempt to make the optimistic case for unemployment. The last thing on HR departments’ minds was switching their remaining employees onto new and untested health plans, and the healthcare industry was in crisis mode itself. Insurers, brokers, and hospital systems were triaging and surviving. Meanwhile, the individual insurance marketplaces ICHRA depends on were themselves in chaos; no one knew what COVID would do to risk pools or pricing.

The timing could not have been better, in retrospect.

COVID exposed the weaknesses of employer-sponsored insurance with brutal clarity. Millions of Americans lost health insurance right when they needed it most.

Personally, I’d quit my job in late 2019 and had just run out of COBRA when I got COVID in March 2020; unemployed and uninsured, I rode it out in our small Brooklyn apartment at a time when we had no idea how serious COVID could be instead of risking uncovered hospital bills. The absurdity of tying healthcare to employment had never been more apparent, to me or to the country.

The pandemic was terrible for insurers, too.

“COVID messed everything up and we’re still dealing with the fallout,” a16z’s Julie Yoo told me. “Carriers continue to not be able to predict utilization rates across the system. People who didn’t get surgeries are doing it now. People who didn’t get screened for cancer during COVID are dealing with more advanced cancer now.”

Perfect timing for something new.

Still, Julie was honest about the fact that “every five years or so, there’s another wave of ‘This is unaffordable! Costs keep growing!’ But the fix never actually happens.”

Mario at Oscar Health, which I wrote about in January 2022, expressed caution, as well: “We’ve been here before. ACA, private exchanges. The US healthcare system has shown remarkable inertia.”

But Julie, Mario, and everyone else I’ve spoken to, believe that ICHRA really will be different.

“It all ties to: how practical are the solutions?” Mario explained. “Private exchanges were impractical because employees had to go to carriers and make deals. ICHRA is more practical.”

Julie, too, is optimistic. “There’s really been this two to five year confluence of factors that have broken the wall,” she said, “and now we’re starting to see true innovation happen.”

Enter Thatch.

Thatch’s Journey to ICHRA

When Will Manidis first introduced me to Chris and Adam, and when Not Boring Capital invested in Thatch, they were building a way for patients to access precision oncology trials.

The problem was personal to them, as both Chris and Adam had lost parents to cancer, and their experience working in cancer research, biotech, healthcare, and fintech made them uniquely well-suited to solve the problem.

As Chris recounted on the Pear Healthcare Playbook podcast, though, speaking with cancer patients, they realized that most actually weren’t looking for new clinical tools. They liked their oncologists. What they kept saying was that paying for care was frustrating and expensive. For a team experienced in healthcare and fintech, that seemed like a problem they might be able to solve. So they started talking to people again.

At one point that September, they asked me to share what they were working on on Twitter so they could find more people to speak with. I’ve never been more flooded with requests. Clearly, they’d hit on something.

Not clinical trials, then. Something to do with healthcare payments.

While they were figuring out what exactly that something was, Chris and Adam were also doing all of the administrative stuff any new company needs to do to get itself up and running, like insuring its growing employee base.

Experience shapes awareness. Awareness shapes reality.

Millions of people have gone through the experience of setting up insurance for their companies. Practically all of them have found it painful in one way or another. The percentage of them that have tried to do something about it rounds to zero.

“For employers, healthcare spend is one of the top five budget line items, they can’t control it, and it always goes up,” former Google Chief Human Resources Officer (CHRO) Laszlo Bock, one of the architects of modern Silicon Valley people practices, told me. “Every year, Aetna sends an email and says, ‘Premiums are going up 8% or 12% this year.’ Startups are always cash constrained, and healthcare is the one lever they have zero control over.”

Thanks to their unique set of experiences, though, Chris and Adam realized they might be able to exert some control.

The first thing that makes Chris and Adam unique is their almost irreverent belief that healthcare can be fixed. Having seen at a young age that the healthcare system doesn’t always work, they don’t view it with the same religious awe that others might. While modern medicine is a miracle, the system we’ve built around it can and should be improved.

“I actually think we don’t have as many entrepreneurs in healthcare today because how could you want to disrupt something you venerate or hold in such high esteem?,” Chris said on the Pear podcast. “Sometimes, having a bad experience early on opens up a window to question the things we take for granted.”

This belief is why Chris and Adam went into healthcare in the first place, and why they decided to start a company together to improve the system.

Then, there was a bit of lucky coincidence, or synchronicity, in the form of well-timed terrible experiences with health insurance.

The week that Chris left his job to start Thatch, he tore his achilles. After surgery, he showed up to physical therapy and was turned away because his insurance company had clawed back charges for his treatment and said that he owed $20,000. Dealing with insurance was almost as painful as tearing the tendon that connected his calf to his heel.

Limping and unable to do physical therapy, Chris still had a company to run, which meant hiring people and giving them insurance. From the beginning, founded when it was in the middle of a pandemic, Thatch has been a remote company, which added complexity to an already complex process.

Originally, Thatch selected an insurance plan based in Austin, where Chris lives, but the plan didn’t work for everyone on even a small early team. One employee wanted to keep using Kaiser, which he’d used and loved in a past job (Kaiser is one of the rare examples of a health system people love; both a health system and an insurer, its incentives are aligned with those of its patients). Another employee, based in New York, found that the plan didn’t cover any of her doctors, including the primary care physician he’d seen for years. One-size-fits-all plans fit almost no one on the team.

So they switched plans, and in the process, while on a long-anticipated and rare vacation with his mother to Japan, Chris got texts from his employees complaining that they couldn’t see their doctors or pick up prescriptions. Coverage had lapsed during the transition. On the other side of the world, Chris woke up at 3am Tokyo time to call the insurer and get the coverage reinstated (he couldn’t, of course, just do it online).

They kept looking for something that would work for their employees, an annoying back-office distraction while they spoke to customers to figure out exactly what Thatch should be building.

That’s when Chris and Adam learned about ICHRA.

Here was a regulation that solved exactly the problems they’d just suffered through - the one-size-fits-none coverage, the lapsed transitions, the employees who couldn’t keep their doctors – and the problems with cost unpredictability that they would inevitably face if their company grew.

But ICHRA was so complex to implement that even they, with deep healthcare and fintech experience, struggled to make it work. If they couldn’t figure it out easily, a normal business wouldn’t stand a chance.

With awareness earned through experience, Chris and Adam could see that ICHRA’s time had come, and that they could pull it forward.

ICHRA’s Why Now?

I am a simple man. I think that the most important question when evaluating a startup is “Why Now?” As I wrote in Better Tools, Bigger Companies:

People are smart. We’ve solved most of the challenges that are possible to solve given the tools currently at our disposal, give or take a little given the fact that we’re also good at getting in our own way. So we build new tools to tackle new challenges.

That’s why investors like to ask, “Why now?” What new technology (or regulation or societal shift, but mainly technology) makes it possible for you to solve this now better than anyone else in all of human history has been able to?

In that essay, I was dismissive of regulation and societal shifts, because the vast majority of large startup outcomes come as a result of a technological shift. This is why I’ve been so focused on Vertical Integrators and hard tech companies; the cost of the technologies in the Electric Stack continue to drop, and their performance continues to improve, making it possible to build companies on products that are better, faster, and cheaper than what the incumbents offer. We’ve had software and the internet for a while; most of the biggest problems that can be solved with software, have been.

Every once in a while, though, changing regulation and societal shifts create the conditions to build something truly massive and societally important with existing technology.

I believe that ICHRA, and our breaking healthcare system, is one of those opportunities. I will lay out the Why Now for ICHRA and then cover how Thatch is both seizing and accelerating the rare opportunity to transform a multi-trillion dollar system.

First, we need to understand why something like this hasn’t happened yet, why, as Mario said, “The US healthcare system has shown remarkable inertia.” Why, specifically, most companies haven’t switched from group insurance to individual.

When I asked Chris and Adam this question, Chris gave me a simple way to think about it. “The switching costs of moving to a new type of insurance plan are really high,” he said, “so companies don’t switch unless their insurance costs are rising even faster.”

This insight is really useful in thinking about who will switch to ICHRA, and when. For most businesses, the decision of which health insurance plan to offer employees is based on how much it will cost them per employee per month to provide a certain level of coverage.

That graph is obviously dramatically oversimplified. In reality, are so many variables that I have to put them in a footnote1 to maintain the flow, and even in the footnote, I probably captured ~5% of the complexity.

All of which is to say, that graph is not entirely accurate because it’s impossible to make a single graph both comprehensible and accurate. But it’s a useful model that roughly represents the state of play today:

The higher the group premiums relative to individual premiums, and the easier it is to navigate ICHRA, the more likely it is a company will switch.

ICHRA makes a lot of sense for small businesses.

It’s starting to make sense for mid-market businesses.

It doesn’t yet make sense for large businesses.

From this simple model, we can start to play with different variables and understand “Why Now?” for ICHRA, or more specifically, when ICHRA will make sense for which types of businesses.

The biggest Why Now for ICHRA is simply that insuring employees is getting increasingly expensive, and unpredictably so, for employers.

From about 2010-2024, Chris said, we were in a low background inflation environment. Because healthcare costs normally increase at 2-3% higher than inflation, companies had been seeing their costs rise 6-7%, right in line with the 2025 Milliman Medical Index average.

Today, however, group insurance is getting so expensive that it is overcoming switching costs.

In early September, the Wall Street Journal published an article, Health Insurance Costs for Businesses to Rise by Most in 15 Years, that shared benefits consultants’ surveys which found that employers expect their healthcare costs to rise 9.2-9.5% in 2026.

Those are averages. Chris told me that some smaller companies are seeing their healthcare costs rise as much as 30% in one year. The WSJ spoke with Troy Morris, the CEO of 20-person Kall Morris Inc., who said that the cost of his company’s health plan grew 20% for the year starting August 1st, after a 9% increase last year.

There are many commonly-cited reasons costs are going up faster now than before:

Inflation: Healthcare costs are super-inflationary, so when inflation grows, healthcare costs grow even faster.

COVID Overhang: As discussed, the healthcare system is still dealing with the fallout from COVID. People are undergoing treatments that they delayed, and dealing with health issues stemming from delayed treatments, like increased cancer rates among the working-age population.

GLP-1s: Even though most employers don’t cover GLP-1s for weight loss, the drug’s popularity and high cost is overwhelming those who do offer it for weight loss, and for eligible conditions like diabetes and obesity, which is a big number! According to KFF, “Over 2 in 5 (42%) adults under 65 with private insurance could be eligible for GLP-1 drugs, based on current Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications.”

Administrative Costs: There’s that chart that we discussed in our latest Deep Dive on Ramp, that shows that the growth in the number of healthcare administrators has far outpaced the growth in the number of physicians since 2010.

It’s only gotten worse since. According to Physicians for a National Health Program, “Since managed care went into effect in 1970, the number of doctors in America has risen approximately 200%. But the number of healthcare managers (administrators) has risen over 3,800%... There are now 10 administrators for every physician in the United States.” Stuff like pre-approvals, meant to keep costs down, inflated the number of people needed to manage stuff like pre-approvals instead.

Then there’s AI, which, hopefully, at some point, will help solve some of these problems, but for now, is mainly making life more expensive for insurers. Julie at a16z pointed out that, “All of a sudden, because of AI, providers are really good at submitting claims and getting paid.”

Companies like Abridge, which offers “enterprise-grade AI for clinical conversations,” are marketing on the idea that they make doctors lives easier, but they’re selling on the idea that if AI is listening to all of a provider’s conversations, it can catch everything that the provider should be billing for and code it appropriately.

V Bento, the founder of Sword Health, explained that healthcare solutions only achieve widespread adoption when they align with the economic realities that the healthcare world faces. “Either they unlock new revenue streams or lower costs,” he said, “and they have to do that without compromising quality of care. That’s the only way solutions get adopted.”

“In earnings calls, healthcare company executives are talking about providers getting better at claim submission, basically admitting that people were getting underpaid,” Julie told me. “It will break the healthcare system in its current form if they have to actually pay out claims.”

“All of these weird esoteric things are creating this total breaking point that calls for the redesign of insurance,” she continued, citing risk-adjustment corrections in Medicare, and their associated abuse, and the same thing happening in Medicaid. It’s all very in the weeds. Her simple takeaway was this:

“Everything [in the incumbent healthcare system] is breaking.”

What does breaking look like?

It looks like higher premiums and an increased willingness to look for alternatives.

In response to such insane increases, the WSJ writes, a “WTW [Willis Towers Watson] survey, which was performed this summer and largely focused on bigger employers, found that 60% were planning to look at replacing their health insurer or pharmacy-benefit manager in the next few years. It also found that nearly a third of employers surveyed are giving priority to new plan designs that could include changes such as limits on access to certain doctors or hospitals.”

To Chris’ point, the rise in healthcare costs are overwhelming switching costs. Six out of ten large employers plan to switch in the next few years. At the same time, employers are looking to limit their plans to decrease costs, a rerun of the HMO playbook. When employees inevitably get mad about limited provider access, they should demand plans that give them choice.

Over time, this becomes a virtuous cycle, or a vicious one, depending on which side you’re on.

So Why Now?

First, there is regulation. ICHRA provides a much-needed alternative to group plans that didn’t exist until five years ago.

Then, there are societal shifts.

COVID, AI, GLP-1s, administrative bloat… all of the biggest buzzwords of this decade have combined to jack up healthcare costs faster than they’ve risen in the last two decades, providing the force necessary to overcome corporate inertia.

And on top of all of that, outcomes are still bad and incentives are still misaligned! Insurers don’t want to pay for GLP-1s because they won’t get the benefit of healthier members in a decade. They don’t want to pay for cancer screenings because another insurer will profit from the life they paid to save. All that money, and it’s not even well-spent on keeping us healthy.

That’s why, Jonathan at Function Health said, “This is not a trend. This is an evolution. For the first time, people are getting agency over their health. It’s a transformation happening in politics, government, and culture.”

“The fact is,” he said, “this is a cultural movement. It’s as much a cultural as a technological thing.”

But another fact is that ICHRA has challenges, too. It is incredibly complex to administer, and that complexity is more than most businesses are able to manage on their own.

This is what Chris and Adam realized when they first tried to implement ICHRA for Thatch, which is why they decided to put Thatch to work on making ICHRA work.

Infra for ICHRA

The simplest way to think about Thatch is as infrastructure for ICHRA.

The beauty of ICHRA lies in the choice it provides.

The complexity of ICHRA lies in the choice it provides.

To start, ICHRA lets employers give their employees tax-free dollars to spend on any individual insurance plan they choose. There are hundreds of carriers, though, and without software to simplify the process, figuring out which to choose would go something like this.

Employer tells employee they have $1,000 per month to spend on healthcare.

Employee goes to each individual insurance carrier website individually to get information on each plan.

Employee builds a spreadsheet or something to compare plans.

Employee picks a plan and pays for the premium on their own credit card, fronting hundreds of dollars each month.

Employee submits receipt for reimbursement each month.

Employers enter receipts into the payroll system for reimbursement.

Employee, if aware, keeps track of how much they have left after premiums to spend on other covered healthcare services, figures out exactly what is covered, pays for any of those services on their own credit card, and submits receipts.

Employer determines whether those costs were actually covered, and if so, reimburses employee.

Employer manages the ongoing reporting and compliance necessary to offer ICHRA.

When Chris and Adam began looking at offering ICHRA to their team, they looked at other companies that existed to make sense of the process, like TakeCommand and Remodel. Both companies were founded in the mid-2010s to help companies manage earlier HRAs and QSEHRAs, but neither, Chris and Adam realized, had built the infrastructure to make the process seamless. In most cases, they were an Excel-based in-between for brokers, carriers, and employers; better than nothing, but not right for Thatch. Given the high manual costs to serve customers, they ignored the sub-20 employee segment of the market in which Thatch lived in its early days.

Jahanvi at Index had been on the lookout for an ICHRA play ever since Mario at Oscar had told her about it in the very early days. She hadn’t found anything worth backing.

“Early ICHRA companies were very hairy services plays, only focused on cost savings,” she said. “Cost savings weren’t the only thing that mattered. I’d talk to brokers and they’d tell me that even when they found good savings with ICHRA, it was too tough to manage, especially with payroll and expecting employees to float premiums.”

“We tried to offer ICHRA to our own employees,” Adam said, “and realized that it was totally broken.”

Crucially, though, they noticed that it was broken not in some “healthcare is broken what’re ya gonna do” kind of way, but in a way that they were familiar with. It was broken in the way that financial services were broken when Adam got to Stripe in 2015, but a little worse, or like the way healthcare software was when he left Humana a decade ago after four years in enterprise information security.

“When I came to Stripe,” he said, “I used to think that financial services and healthcare were similarly shitty, that both had really shitty APIs.” That was too kind to healthcare. “Healthcare usually doesn’t even have APIs.”

He asked me to imagine a spectrum on which all of the different institutions you might interact with live. On one end are “extremely promiscuous” companies with open APIs with which anyone can integrate. Crypto might be the extreme example here. Financial institutions are in the middle; their codebase may be in COBOL, but they’re open to integrating. On the other end are companies that design systems that are impossible to integrate with without speaking with a human and even inking an enterprise agreement. Healthcare lives here.

Having spent the past seven years tackling “very complicated” financial services integrations at Stripe, why not go after “nearly-impossible” healthcare integrations?

After a year of speaking to customers and dealing with their own insurance headaches, that’s what Chris and Adam decided to do. Instead of rushing to market with a duct-taped solution, they spent over a year in the guts of the system, rewiring everything to talk to each other.

“My thesis on ICHRA was: this is really a product problem, and market timing really matters,” Jahanvi told me. Those two ideas - product and timing - are related, and explain Thatch’s strategy, which goes a little something like this.

Thatch as ICHRA Aggregator

The main benefit of ICHRA is choice. Employers at thousands of companies can choose the insurance plans and healthcare benefits that work best for them from among hundreds of options.

That means that ICHRA demands a neutral platform that connects to all of the parties involved in the system.

The largest opportunity in ICHRA, and, if ICHRA proves as important as I think it will, maybe in all of healthcare, is to build the ICHRA Aggregator.

In Defining Aggregators, Ben Thompson describes the three levels of Aggregators, plus a fourth Super Aggregator classification.

All Aggregators have the following three characteristics:

A Direct Relationship with Users

Zero Marginal Costs for Serving Users

Demand-driven Multi-sided Networks with Decreasing Acquisition Costs

“Aggregation is fundamentally about owning the user relationship and being able to scale that relationship,” Thompson writes, “That said, there are different levels of aggregation based on the aggregator’s relationship to suppliers.”

Level 1 Aggregators, like Netflix, acquire their supply. Level 2 Aggregators, like Uber, do not own supply but incur transaction costs in bringing suppliers onto the platform. They “typically operate in industries with significant regulatory concerns that apply to the quality and safety of suppliers.” Level 3 Aggregators, like Google, do not own supply and do not incur transaction costs in acquiring it.

Thatch is a textbook Level 2 Aggregator.

It has a direct relationship with users. Employees and employers interact with Thatch directly through its app, card, and portal to choose and pay for plans and health services.

It has near-zero marginal costs. Thatch’s core product is software and payments rails (APIs, card, automated enrollment/payroll flows), which scale digitally. Each incremental employer and employee adds minimal variable cost relative to the underlying insurance spend borne by carriers and providers.

It has demand-driven multi-sided network effects with decreasing acquisition costs. Thatch aggregates employers and employees on one side and carriers, brokers, and health services (e.g., Sword, Oura, Prenuvo) on the other via its marketplace. As more demand shows up, more suppliers integrate, and offer more products, reinforcing the flywheel.

It is Level 2 specifically because while it doesn’t own its supply - insurance plans, providers, or services - it does incur transaction costs to bring supply onto the network in the form of integrations, often with companies that rarely integrate.

In the short-term, as Thompson writes, “This limits supply growth which ultimately limits demand growth.” In the long-term, however, it makes Thatch more defensible.

For Thatch, that looked like spending a year building integrations with many of the nation’s biggest carriers directly and payroll providers like ADP (and more), not to mention the financial and compliance rails underpinning it all.

Because of the way carriers view integrations, by getting there first, Thatch may be the only, or one of maybe three, platforms with which each carrier integrates. Missing APIs are a pain until they become a moat. The same is true on the payroll side. From a product perspective, it doesn’t make sense for a payroll provider’s website to show 100 healthcare options; they just want to show the best.

“One thing we did differently,” Adam said, “is that we started by building everything self-serve. Any business can come to Thatch, connect their bank and payroll system, set a budget, and get going in less than 10 minutes.”

Because of those early choices, Thatch is able to serve the entire ICHRA market, including the sub-20 person companies that need it most today but are least equipped to manage it themselves and have been ignored by incumbent HRA platforms. Today, 65% of the insurance process is automated, with a line of sight to 90%, so Thatch doesn’t incur the steep costs of serving small customers that others do.

For larger customers – everyone from Jersey Mike’s to mid-market trucking companies to leading AI labs – Thatch’s sales team can help think through all of the intricacies of switching plan types and shifting responsibility to individual employees.

In these early days for both Thatch and ICHRA, the company is almost entirely focused on customer experience. That, they believe, kicks off an Amazon-like flywheel that makes both Thatch and ICHRA inevitable.

Because ICHRA isn’t quite inevitable, yet.

Challenges with ICHRA

For one thing, while it enjoys support from both Republicans and Democrats, there is always the chance that it can be killed. Healthcare is a divisive political issue, and as Chris put it, “ICHRA’s blessing and its curse is that it’s tied to the ACA.”

It is a blessing because it taps into and shares risk pools with the ACA’s individual markets. It is a curse because the ACA is one of the most heated political issues of this century to date.

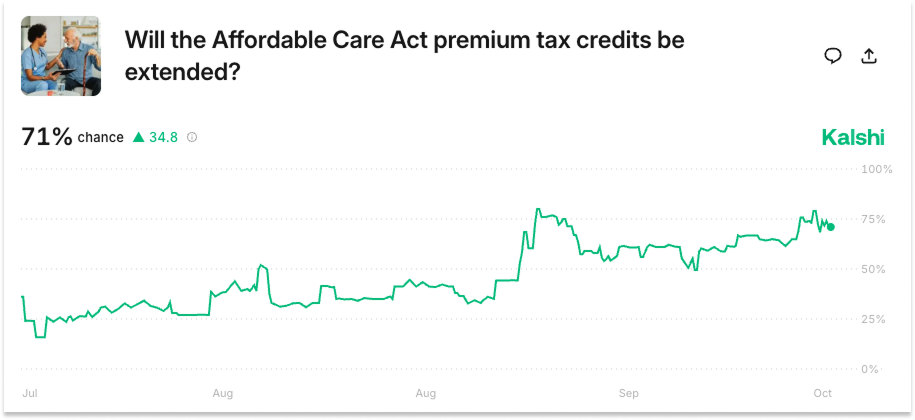

More practically and immediately, individual rates are tied to the ACA’s individual markets. As those markets grow, rates should come down; ICHRA is part of the ACA risk pool. At the same time, though, rates are subject to political dealing. As I write this, the US government just entered a shutdown in large part due to Democratic opposition to the Republicans’ plan to end the ACA’s premium tax credits, which could push individual rates up by 2-3%.

Everything in insurance, Thatch’s Gary Daniels told me, is “a matter of volume,” and 2026 could be rough on volumes because of policy uncertainty. If people think rates are going to go up, then individual plans make economic sense for less of the market, which means a smaller risk pool, which means rates actually do go up. “Cost is always the core driver,” Gary said.

That said, it still seems likely that the credits will be extended by the end of the year. A Kalshi prediction market on the extension rose from a low 15% chance in July to a 79% chance pre-shutdown, and remains at 71%.

In fact, it is looking increasingly likely that the government will accelerate ICHRA adoption.

While a provision to turn ICHRA into law as “CHOICE,” and provide employers with a $100 per employee per month tax credit for enrolling in ICHRA, was struck in the late rounds of negotiation on the Big Beautiful Bill, it seems that a standalone CHOICE bill, with the tax credit in place, could hit the floor imminently. Two weeks ago, a separate bill, the Small Business Health Options Awareness Act of 2025, was introduced which would require the SBA to provide more outreach and education on ICHRA to small businesses.

If either or both of these pass, Thatch will be in an enviable position: the government will be marketing ICHRA to small businesses and incentivizing its adoption with tax credits. Because it has spent years building self-serve infrastructure, Thatch will be best positioned to deal with the flood of demand if this happens.

Gary told me that he normally falls asleep pretty quickly at night, but the thing that’s been keeping him up is how to deal with all of that volume without messing up.

When you fuck up and people can’t get enrollment and they have a sick kid and you can’t help them… that’s the worst thing you can do is impact someone negatively when they need care. I remind our people: our #1 priority is to not mess up that experience.

Fortunately, no one else in the industry has built what Adam has built. That we can quote, install, and have an incredible experience with no one being engaged.

That technology will be critical. If a CHOICE bill passes this year, Gary said that 2025 small business volumes could be 4x higher than anticipated, all squeezed into the last couple of months of the year. We have seen what this kind of demand can do to health insurance systems before. Luckily, Adam and the team he’s built are a whole lot better than whoever built the original healthcare.gov.

Volume, whether driven by a Bill or by time, will be the key to solving the other major challenge ICHRA faces: plan quality and coverage limitations.

The individual health insurance market today faces a fundamental adverse selection problem that significantly limits plan quality and coverage options. With approximately 24 million Americans enrolled in ACA marketplace plans as of 2024 (less than 8% of the U.S. population), carriers operate in a constrained risk pool that makes offering comprehensive benefits financially untenable.

This is a real concern. When Mario at Oscar recently asked one innovative HR leader why they don’t yet offer ICHRA, the response was blunt: “All of the ACA plans suck. They’re high-deductible, they don’t cover certain drugs.”

He told me that while there are great plans – Oscar’s whole business is individual market plans – “that’s still a real argument compared to large group plans. Take fertility benefits; there’s not a single ACA plan that offers IVF.”

The economics are straightforward: when any carrier offers enhanced benefits like fertility coverage, they immediately attract a disproportionate share of high-cost members without sufficient healthy enrollees to balance the risk, creating an unsustainable “death spiral” that forces them to either withdraw the benefit or exit the market entirely. “If you’re the one local plan that does offer IVF,” Mario explained, “everyone who needs IVF will go to you and you will go underwater.”

More generally, Mario, who is a strong believer in ICHRA and the one who turned Jahanvi on to it in the first place, is worried that ICHRA could become viewed as “this low-end disruption thing, where it becomes this cheap option for employers.”

There’s no reason that has to be the case, though. When I asked him how he would solve the IVF issue and the cheap plan issue, he pointed to Thatch’s role as an Aggregator.

“Thatch needs to go to employers and say, ‘If you want to offer ICHRA, and you don’t like your local network – the drugs, doctors, etc… - I will go to Oscar and United and whoever and get them to design the plan for you.”

This is a crucial point! The infrastructure matters, but infrastructure can’t fix a broken $5.6 trillion system alone. What matters is how Thatch’s aggregation reshapes supply.

How Thatch Can Help ICHRA Win With Scale

I have been an investor in Thatch for over three years, and it’s one of those companies that I get more excited about every time I talk to the founders.

But this realization - that by aggregating demand and giving individuals choice, they can influence where money flows in healthcare - is the thing that made me believe the investment will be a fund returner and the company will rewire US healthcare.

One of the most powerful attributes of being an Aggregator is that controlling demand allows you to reshape supply.

Uber doesn’t employ its drivers, but its rating system incentivizes drivers to provide a certain level of service. Airbnb doesn’t own its homes, but its rating system incentivizes owners to provide the best experience possible. Google doesn’t own the websites it indexes, but there is an entire industry, search engine optimization, whose job it is to shape websites in a way that will please Google’s algorithm. A similar dynamic exists for each Aggregator.

Similarly, every Aggregator both drives and benefits from scale. The more drivers on Uber, the shorter the wait time, the better the experience, the more demand. The more homes on Airbnb, the more choices in a given market, the better the experience, the more demand. From the driver or homeowner’s perspective, the more customers on Uber or Airbnb, the stronger the signal to come online and provide a better experience.

The core insight behind Thatch is that, with employee-funded individual markets, a similar dynamic can exist in healthcare.

The core issues with the individual market today are size and adverse selection.

The individual market is 24 million members compared to the 154 million people in employee-sponsored group insurance. Many of these 24 million people today are those who can’t get employer coverage because they’re unemployed, gig workers, or between jobs or who have pre-existing conditions and require ACA protection. In short, they are lower-income and more expensive to cover.

This creates a vicious cycle. Carriers price plans defensively because the risk pool skews sick and poor. Higher prices drive away healthy people who have any other option. The risk pool gets worse. Plans get more expensive and offer fewer benefits. The cycle continues.

But ICHRA breaks this cycle by bringing employed, insured people into the individual market.

The math is compelling. If even 10% of the employer market shifts to ICHRA, that’s 15 million people added to the individual risk pool, a 60% increase. More importantly, these are exactly the lives carriers want: employed, with steady income, and critically, with the full spectrum of health needs that makes insurance actuarially sound.

As Thatch explains in an internal strategy memo, “The fundamental principle of insurance is simple: the larger the risk pool, the better the pricing and superior selection due to increased competition.”

Combining this insight with the observation that we made earlier – that ICHRA with Thatch is currently a better option for many small businesses and an increasing number of mid-market businesses – we can understand Thatch as a series of flywheels as it grows the number of members covered.

There is an Amazon-like flywheel that Chris and Adam reference when talking about their business:

The better the customer experience, the faster we grow our employer and member base, which in turn attracts carriers and marketplace partners to the platform, with better and cheaper products. These better and cheaper products (relative to traditional group products) will attract more employers, and their members, perpetuating the flywheel.

There is a bit of a twist, because of how insurance works. Since risk pools are often based on group size, and because pool size influences price and selection, you can think of this flywheel spinning in progressively larger markets, almost capturing enough momentum from one to tackle the next.

This is another critically important thing to understand about Thatch.