Ramp at $1 Billion

Inside the Time Company: Saving Time, Compounding Over Time, Fighting Time

Welcome to the 1,324 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 249,839 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Tuesday!

One of my goals for this newsletter (and Not Boring Capital) is to find a handful of generational companies as early as possible, write their story in chapters over time, and then publish the whole thing as a book when they IPO.

Ramp is the model. I first wrote about the company in December 2020, when it was valued at $300 million and doing something in the single-digit millions in revenue. Even then, it was obvious that something special was happening, and I invested both personally, before I had a fund, and then through Not Boring Capital.

But early hype often fades. What’s been most remarkable in writing about Ramp three times since is that each time, the new reality outruns the old hype.

Ramp is the rare company that gets better and moves faster with time.

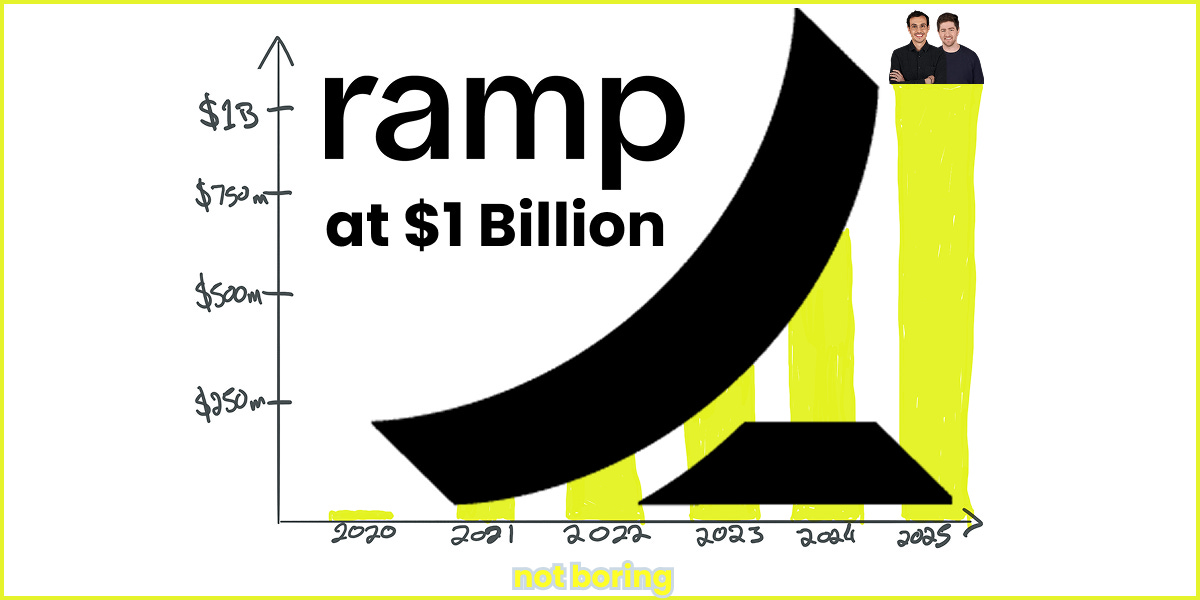

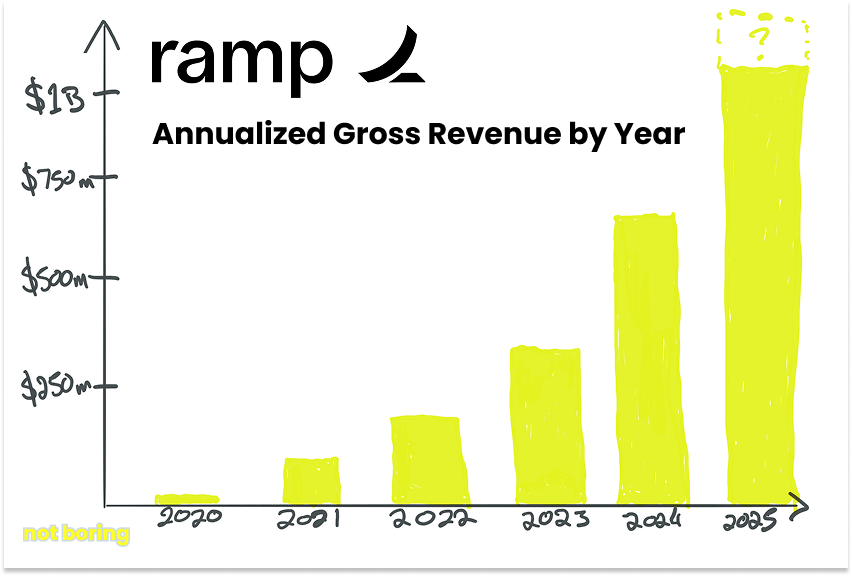

Today, Ramp is announcing that it’s crossed $1 billion in annualized gross revenue while doubling year-over-year and generating positive cash flow. In celebration, I’m taking another snapshot in time to look at where the company has been, where it is today, and what it might grow into in the fullness of time.

This is the latest chapter in a story I’ve been writing for years, and plan to keep writing for many years to come.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Framer

Framer gives designers superpowers.

Framer is the design-first, no-code website builder that lets anyone ship a production-ready site in minutes. Whether you’re starting with a template or a blank canvas, Framer gives you total creative control with no coding required. Add animations, localize with one click, and collaborate in real-time with your whole team. You can even A/B test and track clicks with built-in analytics.

Ready to build a site that looks hand-coded without hiring a developer? Launch your site for free at Framer dot com, and use code NOTBORING for a free month on Framer Pro.

Ramp at $1 Billion

A little over four years ago, on April 8, 2021, I wrote about Ramp’s Double-Unicorn Rounds.

At the time, Ramp was just two years old. In the piece, we announced that Ramp had raised not one, but two rounds. D1 led a $65 million financing at a $1.1 billion valuation. Stripe came in with $50 million at $1.6 billion.

I knew that that would seem crazy on its face, a real-time symptom of COVID-era excess: a company that young raising at those valuations in that structure. So I wrote a section in the Deep Dive titled “Has Venture Capital Lost Its Mind?” which argued that no, it hadn’t, or at least, that Ramp’s back-to-back fundraises weren’t proof that it had.

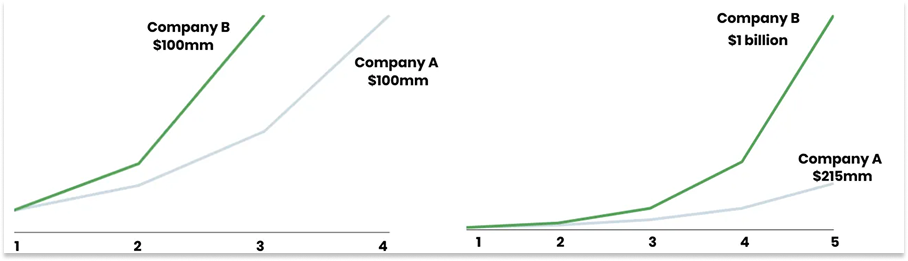

The logic was: growth matters, and it matters more the longer it lasts.

Take two companies, Company A and Company B. Company A reaches $100 million in four years, growing 115%. Company B takes three years, growing at 216%. In year five, Company A will be at $215 million in revenue. Company B will be 5x higher: $1 billion.

Back then, of course, the $1 billion revenue number was hypothetical. I was just making a point that growth trajectory matters.

Today, it is not.

Today, Ramp is announcing that it has crossed $1 billion in annualized gross revenue.

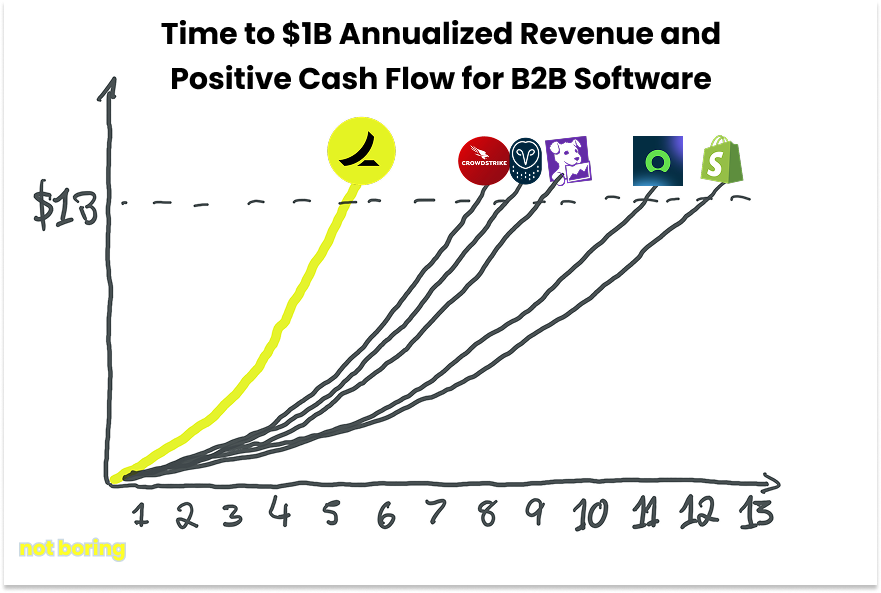

That milestone, achieved in just six years since incorporation, five-and-a-half since product launch, and three-and-a-half since crossing $100 million in annualized gross revenue (annualized revenue), is extraordinary on its own.

That the company is roughly doubling revenue year-over-year crossing the milestone is even more noteworthy. According to an analysis that Founders Fund Partner Amin Mirzadegan shared with me, it puts Ramp among an elite group of companies - Snowflake, AppLovin, CrowdStrike, OpenAI, and Anthropic - that have grown at this pace while crossing both $500 million and $1 billion in revenue.1 The rest of the group sports valuations north of $75 billion.

In the four previous Deep Dives I’ve written on Ramp, a common theme and question has been: “Wow, Ramp is growing really fast! But can they keep it up??”

That is still a question, but each year that they keep it up, the answer becomes more apparent: yes, they can keep it up, even if it seems improbable based on the classical model of business physics.

Now, the much more interesting questions to ask about Ramp are how they continue to grow so fast, and maybe more importantly, what happens to the business as it grows.

We live in an age of hypergrowth. You can’t open up twitter without hearing about a new company that just became the fastest company ever to $100 million in ARR. Each announcement, though, adds to a growing sense of unease: that none of this is sustainable. Companies burn unsustainable amounts of cash growing products with poor unit economics.

Which makes this next announcement all the more notable:

Ramp is generating operating cash flow.

Which makes sense, because Ramp’s value proposition to its customers is that it will make them more efficient. Efficiency is the result of saving time and money. And if Ramp is all about making other companies more efficient, they better be efficient themselves!

Ramp has crossed $1 billion in annualized revenue while doubling revenue in the past year and generating operating cash flow.

Among all the B2B companies who have crossed $1 billion in revenue at any speed while cash flow positive, Ramp has achieved this milestone years faster than anyone else.

I’ve written about a lot of the things that have contributed to putting Ramp in such great company. Counterpositioning against points-happy incumbents. Engineering-led everything. Trajectory and velocity. Owning the transaction layer. Mission, structure, and talent.

More than any company I’ve ever met, though, the Ramp story is really a story about time.

Ramp is a business focused on saving time that gets better with time.

The Time and Money Company

Time is money. This is an old adage, a Ramp marketing tagline, and the truth.

No company is more obsessed with the relationship between time and money than Ramp.

The business started as a brainstorm about time to money. More specifically, as Ramp CEO Eric Glyman shared on My First Million, after he and Ramp CTO Karim Atiyeh sold their first startup, Paribus, to Capital One, and after they put in a year of making sure the acquisition paid off for the acquirer, they started to think about what to do next.

During that process, they set a goal: to build a company that could be worth $1 billion in 18 months.

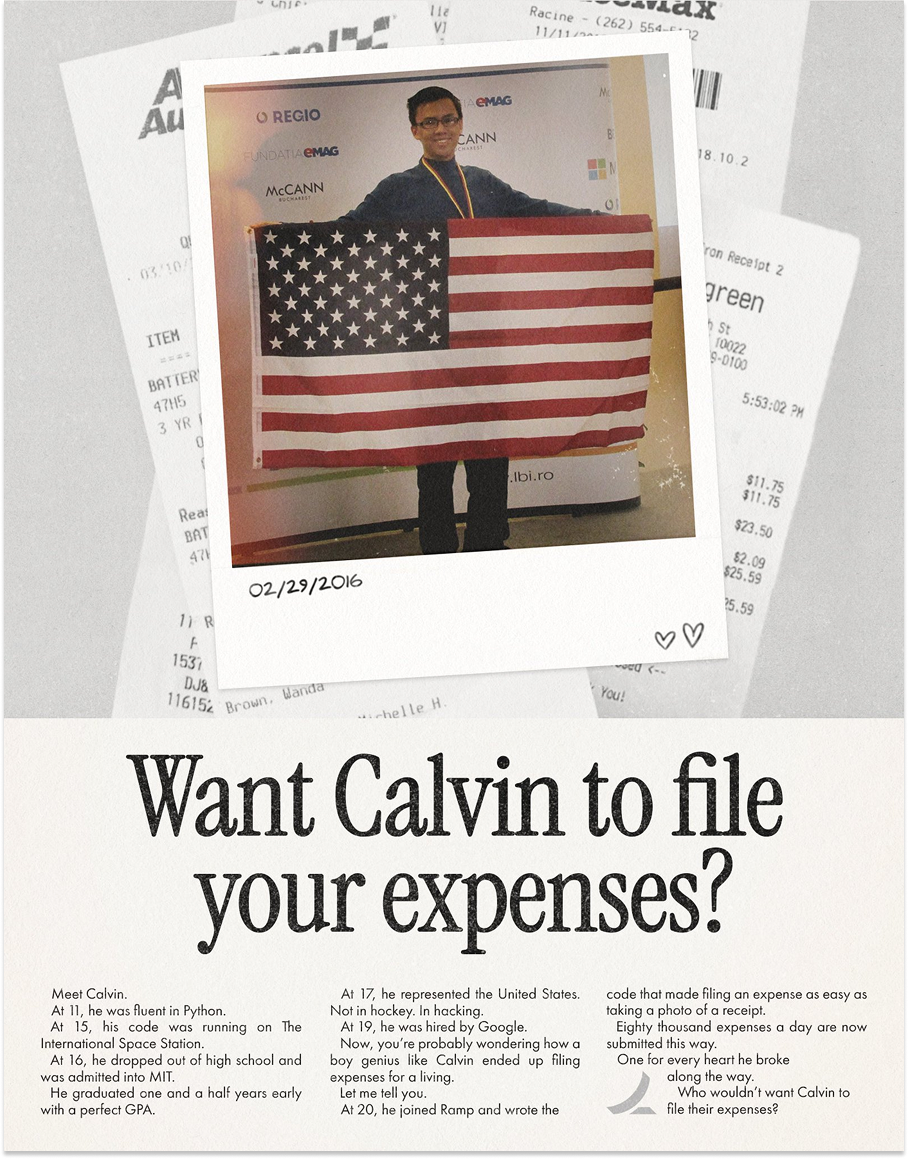

Never mind that no New York City company had ever done that. Calvin Lee, Ramp’s founding engineer turned Swiss-Army-Knife-If-Swiss-Army-Knives-Included-the-Best-Version-of-Each-Tool, looked it up later and found that no New York City company had ever hit the $1 billion mark within three years, let alone 18 months.

Luckily, Calvin looked it up in 2021, after Ramp was valued at $1 billion at just two-years-old. Sometimes it’s better not to know something’s impossible.

At the time of the double-unicorn rounds in April 2021, Eric told Sam Parr, Ramp was doing something like $10 million in annualized revenue. If you viewed Ramp as a snapshot, at that point or almost any point in its history, its valuation seemed crazy. D1 gave it a 110x revenue multiple. Stripe, the next day, valued it at 160x annualized revenue.

A year later, in March 2022, the 2021 valuation didn’t seem crazy at all. Ramp had crossed $100 million in annualized revenue, which meant it was valued at 16x annualized revenue. Then, Keith Rabois at Founders Fund led a round at a new crazy valuation: $8.1 billion, or an 81x annualized revenue multiple.

The markets tanked soon thereafter, and while most companies tried to hold on to their ZIRP-era valuations for dear life, Ramp was one of the first to take its medicine, raising $300 million at a $5.5 billion valuation in August 2023. A company so relentlessly focused on time can’t hold on to the past; it needs to take stock of the present and once again look forward.

As 49ers Head Coach Bill Walsh wrote, and as Eric and Calvin referenced in our conversations, The Score Takes Care of Itself. Get the inputs right, and the outputs follow, in time.

To that end, market conditions be damned, or even perhaps because the value proposition – saving time and money - was more compelling when cash stopped flowing so freely, Ramp continued to grow. Between its $8.1 billion 2022 round and its $5.5 billion 2023 round, it grew annualized revenue three times, to $300 million.

The revenue multiple compressed: under 18.3x on a trailing basis; on a forward basis, Ramp was practically free. Because it kept growing and growing. By June 2024, its revenue approached half-a-billion American Dollars. Its valuation, in its May 2024 funding led by Khosla and Founders Fund, followed: $7.65 billion, good for an annualized revenue multiple of 15.9x.

Then Ramp, by Ramp standards, went quiet. Heads down, growing.

When it popped back up after ten months in the desert in March 2025 to announce a secondary sale at a $13 billion valuation, Ramp called itself “The Time and Money Company.” It ended that quarter above $700 million in annualized revenue. The tender valued the company at 18x revenue. It also meant that the investors who invested at $7.65 billion a year earlier were now sitting at ~10x annualized revenue.

Ramp has not stayed quiet since.

In June, Ramp announced a new round of funding at $16 billion, led by Founders Fund, at an 18.2x annualized revenue multiple.

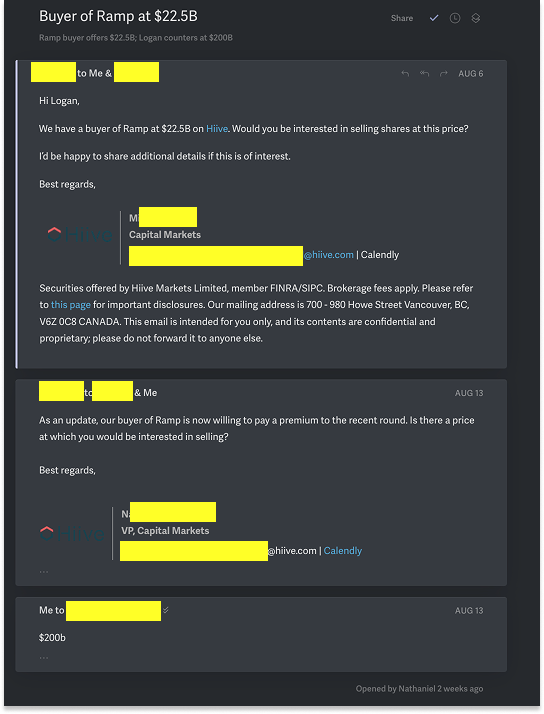

The next month, in July, Ramp announced another $500 million of funding at $22.5 billion, led by ICONIQ, at 24x revenue.

Even at this price, my friend Logan Bartlett, a Managing Director at Redpoint who’s led the firm’s investments in Ramp, has no desire to sell. Is there a price at which he would be interested in selling? $200 billion.

The pace at which Ramp raises can seem overwhelming, but it’s deeply rational. Instead of raising dilutive, multi-billion dollar rounds every couple of years, they raise more frequently in smaller chunks.

It’s not how most companies do it, but it’s how you’d do it if you were a Time Company, if you were confident that the growth would continue.

Plus, the fundraising announcements actually contribute to the growth; Eric told me that each raise contributes to an uplift in excitement, which shows up in marketing qualified leads (MQLs) and sales qualified leads (SQLs) and ultimately, in closed won customers (CW). There’s some “efficient frontier of fundraising,” he half-joked, and no company rides it better than Ramp.

Already, with today’s announcement of $1 billion in annualized revenue, the price looks a little cheaper. In time, it will look cheaper still. In fact, last quarter, Ramp had its fastest growth quarter in a year. This quarter is on pace to beat it.

As Amin at Founders Fund put it, “Ramp should exit 2025 growing faster than it did in 2024, at effectively double the scale. That is very, very rare. And they’re generating cash.”

It’s like solar cost curves: even optimistic forecasts prove not to be optimistic enough.

This is hard to grok, even for those whose job it is to analyze and write about these things. Just yesterday, after I’d written the full draft of this Deep Dive, Anita Ramaswamy at The Information wrote an article arguing that because Ramp is a fintech, and not a SaaS company, “investors are at risk of overvaluing” it.

Ramaswamy made some classic mistakes.

First: understanding Ramp’s business model, which is evolving as it adds new products. The company expects to to have over 30% of its contribution profit come from SaaS, Bill Pay, Treasury, Procurement, Travel, and more by the end of the year.

Not all gross revenue is created equal. Because Ramp keeps more of its gross revenue than many other fintechs, and because it has added higher-margin products like Plus and Travel, it generates operating cash flow on its $1 billion in annualized gross revenue.

Second: comparing Ramp’s current revenue multiple to public companies’ next twelve months’ estimated revenue:

Ramp’s latest fundraising implies [Ramp is] hitting those software-like margins. Fortune reported the company’s $1 billion in annualized revenue last week. At Ramp’s latest valuation, that means investors are paying more than 22 times revenue for the company. That is well above the roughly 13 times next 12 months’ estimated revenue that software companies ServiceNow and Rubrik, with 70% gross margins, trade at.

Third (and most classically): underestimating Ramp’s growth:

Still, even assuming Ramp grows at, say, 50%, for another year, it would still be expensive. At the $22.5 billion valuation, its multiple would be around 15 times, higher than Rubrik and ServiceNow.

Ramp does not expect to grow just 50% over the next year, and it certainly doesn’t plan to stop growing after that. If Ramp continues at its current pace, it’s trading at a discount to the 13x NTM revenue multiple investors are paying for Rubrik and ServiceNow, two businesses that have guided towards much lower NTM revenue growth rates: 34% and 20%, respectively.

It made me happy to read that article because it proved that Ramp is still misunderstood, which means I still have a job to do. Today, we will work to understand.

The thing about Ramp is that it continues to grow faster, for longer, than people expect, and the business continues to get stronger and more durable with time.

Three Flavors of Time

We talk about time as if it’s one thing, as if it marches on unimpeded, unchangeable, even though we know that that’s not how time works.

As an object moves faster, its time appears to slow down. If I sent you to a distant planet and back on a spaceship flying at 99% of the speed of light, and you experienced ten years on the ship, I would be dead by the time you got back. From my perspective, your 10-year journey would have taken 70 years. Einstein grokked this.

Carlo Rovelli, in The Order of Time, goes even further. He argues that time as we experience it is not fundamental to the universe's structure; it emerges from more basic physical processes and our particular perspective as observers within the system. “The idea that a well-defined now exists throughout the universe is an illusion,” he writes, “an illegitimate extrapolation of our own experience.”

Less trippily, but perhaps more immediately alarmingly, Gurwinder wrote in a recent substack, How Social Media Shortens Your Life, that spending time on social media speeds up our sense of time and effectively shortens our lives.

Time is more malleable than most of us normally consider.

Ramp, more than any other company I know, considers time’s malleability. Its recipe is a blend of three flavors of time:

Saving Time

Compounding Over Time

Fighting Time

It builds products that save customers time. These products compound over time, and strengthen each other. And as an organization, Ramp is designed to fight the entropy that normally comes with time.

Understanding those three flavors of time, then, is the best way I’ve found to understand Ramp.

Saving Time

One of the reasons that Ramp has been able to grow so fast for so long, as Eric will readily admit, is that it is playing in an almost bottomlessly large market.

Even after all of the growth to date, “98.5% of businesses in America don’t use Ramp’s core product,” Eric is happy to point out, “and that number is misleading, because nearly 100% don’t use the additional products Ramp is building. So our real market share is closer to 0%.”

There are roughly 15 million businesses in the United States, 3.5 million of which have five or more full-time employees, 2.8 million of which use cards. Ramp serves just north of 45,000 of them. Visa estimates that businesses in the US spend >$40 trillion per year, of which $2.1 trillion is spent on cards.

According to Visa, there is $145 trillion of annual business spend up for grabs globally. Money itself is the largest TAM there is. Visa, relevantly, wrote, “In the $145 trillion of B2B, go spend time with like the function inside your company that is doing buyer supplier payments, and you will just, you might be surprised at how much manual work is still going on there.”

But entering an existing market that large is a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, it is large. There is room for growth, and for many winners.

On the other hand, it is competitive. There are many competitors chasing that growth. AmEx is a $230 billion business. JPMorgan Chase, the country’s largest bank, is an $835 billion business. Other startups are fighting for that growth, too.

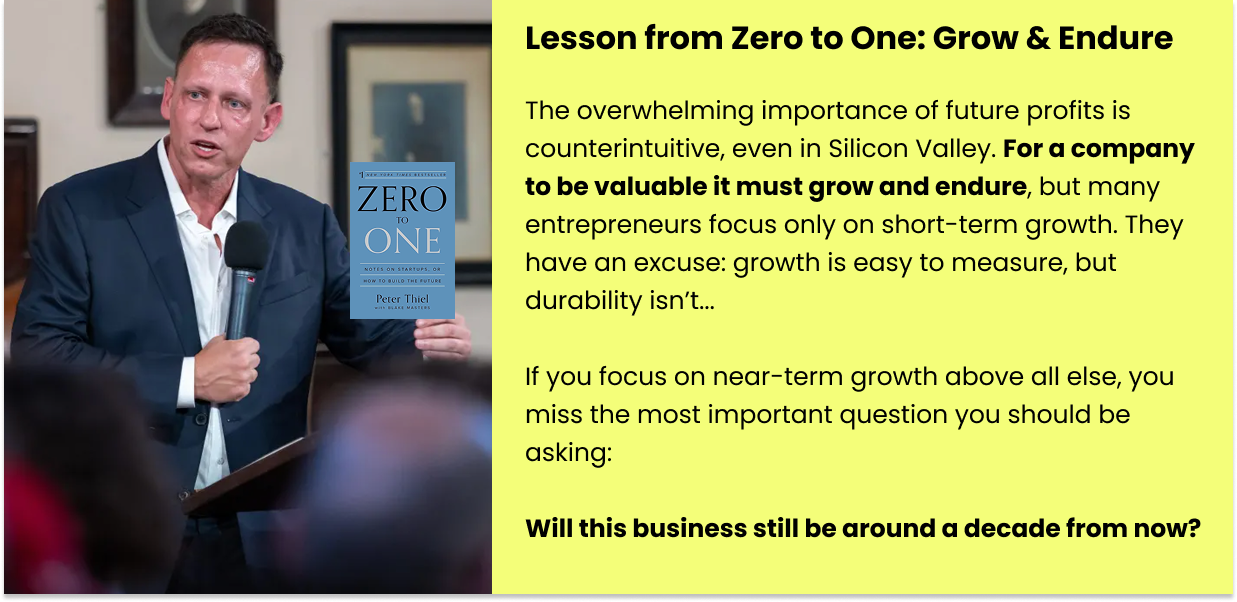

As Ramp investor Peter Thiel famously wrote in Zero to One, “Competition is for losers.”

And yet…

As we’ve covered since the beginning, when Eric and Karim set out to figure out what to build next, they realized that while the corporate card market seemed saturated, there were two wide open attack vectors:

Saving Customers Money. This was classic counter-positioning. Since card companies make more money the more money their customers spend, they’re all incentivized to get customers to spend more, so they offer points and rewards. But businesses do better if they spend more efficiently, so what if you built a business that helped them do that?

Saving Customers Time. Existing card companies, even startups, were sales and marketing-driven. There was an opportunity to build a product and engineering-driven financial software company, starting with a card, whose products helped companies get back the one thing they can’t buy more of: time.

Those vectors are related. Plowing interchange revenue (the ~2% card companies make when you use their card to pay) back into better software instead of points and rewards meant that Ramp could use the card as a wedge into all sorts of products that help save time and money, which, as a product and engineering-company, they were best-positioned to build.

This is a surprisingly deep insight.

One of my favorite ways to spot an exceptional founder is to see how deep down all of their industry’s rabbit holes they’re able to go. Sometimes, when you talk to Eric, or hear him speak on a podcast, because he’s so nice, you can forget how sharp he is.

But when we were chatting the other day, and I asked him what he’s been able to learn from AmEx about building a brand, he went deep. If you’ll allow me the slight digression, I think it’s a useful glimpse into how Eric and Ramp think.

In a 2007 speech at the Economic Club, former AmEx CEO (and current Ramp investor) Ken Chenault shared an important idea that Eric has taken to heart: great companies understand that their product and their brand are separate things. The products you sell work in service of the brand you promise.

“Many once-great companies lost to time” - there it is again - “thought they were selling products and things – and you do want to sell amazing things that work well and make peoples’ lives better - but the once-great got lost in the form factor, in being the finest horse and buggy manufacturer when the car came,” Eric said.

AmEx has been around for nearly 170 years and started as a pony express.

“What does horse-driven delivery have to do with cards and points?” he asked.

“They weren’t selling spots on the back of a horse-drawn carriage. They were selling trust.”

The thing that you wanted to transport, or the money that you wanted to move, was going to get there. You could count on American Express to deliver it for you.

Then came travelers' cheques. Even in a strange, foreign land, you could trust that with AmEx, your money would work.

Then came credit cards. Anywhere you go, AmEx will make sure your money works.

Now it’s worth 60x what it was four decades ago, because it’s evolved its products to meet the standard of its brand.

“Think about the brand over time,” he said. “In the ‘80s, ‘Membership has its privileges.’”

“Today, ‘Powerful Backing.’ There’s always been this element of trust, and of ego. Wherever you are, you know that AmEx has got your back, that membership matters, and that you can always count on AmEx.”

Think about the experience of calling AmEx as a member since 1997.

“You’ll call, and you won’t wait, and someone will be on the other end of the line, and they’ll say, ‘Hello, Mr. McCormick. Thank you for being a member since 1997.’ That’s cachet.”

The idea that “you matter more here,” he said, is a big part of the AmEx brand.

AmEx’s is an ‘80s idea of luxury: “The Bentley, the Platinum Card. Of course they pick up your call, get you the best table, get you cool tickets. It’s almost an old-world luxury, Mad Men luxury.”

“But I would argue,” and I had not yet realized that this was going to be an essay on time, or, therefore obviously, discussed it with Eric, “this idea is sort of stuck in time.”

What Ramp realized, and AmEx didn’t, is that time changes, and time is different now than it was in the 1980s.

“What’s changed,” Eric said, “is that now there’s a constant assault on your time.”

On a Saturday morning in the ‘80s, no one could call your cell phone – you didn’t have one. Now they can. Emails can get you. Notifications on social media can get you. Work is always there with you, in your pocket.

Things just keep piling up, and people want things that help them fight back.

“It was luxurious back then to be able to call and have AmEx solve a problem for you. Now, it’s more luxurious not to have to call in the first place.”

“Not having to do an expense report, having the tedious stuff done for you so you can actually live your life. Trust and luxury are good, but you need to understand what luxury actually is today. Luxury today is time.”

Since Ramp was founded in 2019, though, AmEx’s stock has tripled, even though if you look at the AmEx website in the Wayback Machine, and look at the products and cards they were selling then, they’re the same as when Ramp was founded.

What happened was that AmEx got serious about consumer rewards and lost focus on business customers: Resy reservations, CLEAR, WalMart+, hotel credits, live events. They upped their annual membership fee from $540 to $695 and … practically no one left. The money just dropped to their bottom line. Today, they’re booking millions of tables per week. If you want to go to the US Open in style, or to Carbone, you need AmEx Platinum. They reinvented themselves as a consumer membership company, refocused on who they were, and it turned out incredibly well.

Practically, for Ramp, this means they entered a seemingly crowded Corporate Card market, but what they found was a large market with no one else focused on the new luxury that is time.

And if you look at the other categories that Ramp has expanded into, the same thing is true. In expense management, SAP bought Concur in 2009 and left it somewhere near the bottom of the priority stack. If you’ve used Concur, it is not focused on saving you time. In Bill Pay, you know how I feel about bill.com, and my sentiment is not, “Wow, these guys save me a lot of time.” There are countless other companies in these categories owned by PE and more focused on near-term bottom line than on saving customers time.

With trillions of dollars of market cap and tens of trillions of dollars of spend on the line, Ramp keeps finding markets surprisingly bereft of competitors focused on the thing they believed matters most to businesses: time.

Enduring companies don’t confuse the product with the brand. They build products in service of the brand promise. Ramp’s brand promise is that it will save businesses time. So they build products to do just that.

When we spoke recently, Karim reiterated this point. It was the first thing he said:

“For every product we build, and everything we do, the goal is always, ‘How can we save more time for customers?’”

“Even in very early Ramp, when we built our mobile app…” he said, “think about mobile apps built at the time. They were all about trying to get MAUs and DAUs. That might be right for social media, but we had the totally opposite metric: how can people spend as little time as possible in the app? When someone clicks in the app, what are they trying to do, and how can we make that faster?”

Diego Zaks, Ramp’s VP of Design, says that the company’s goal remains for its customers to NOT spend time on Ramp. They benchmark against this internally: how much time are customers spending on the platform and how can we consistently make that go down over time? The goal is that the more powerful Ramp becomes, the less time you spend on it. This is where AI comes in and is why they’re so focused on agentic work.

“This is true for all of the new products we build,” Karim went on.

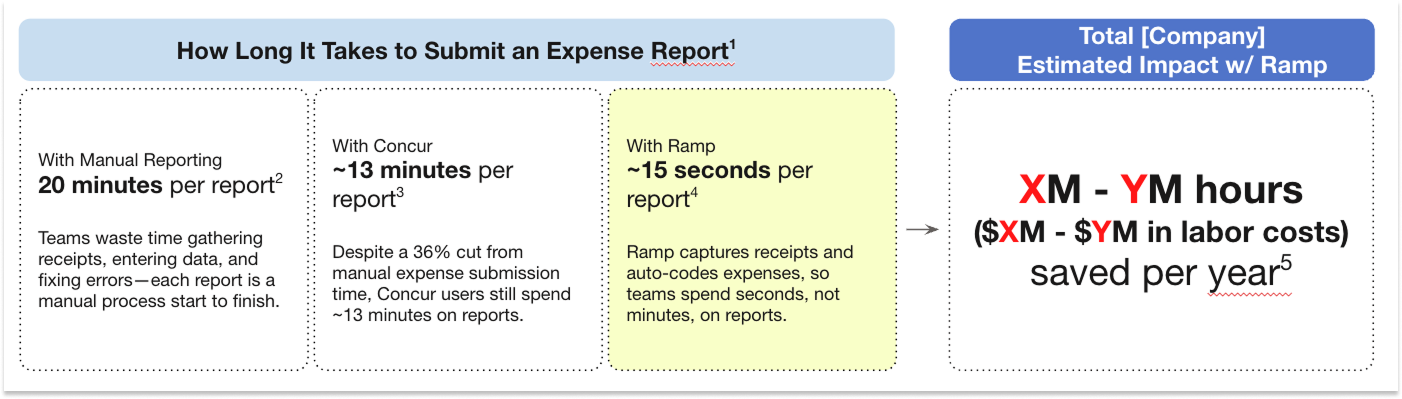

It started with Card and Expense Management. If your expense management software was tied to your card, could see each transaction, you can turn “a complicated guessing problem into a simpler matching problem” and save hours of back and forth. As a result of that and many improvements since, Ramp can reduce the time it takes to submit an expense report by 98%.

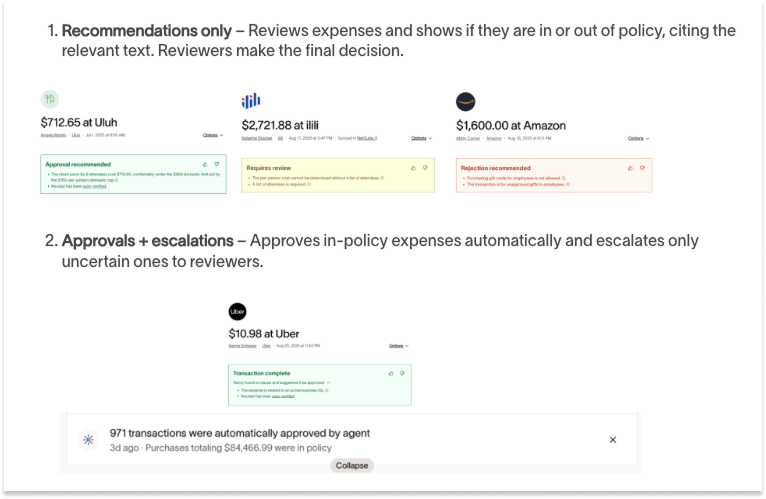

Today, Ramp’s Policy Agents can proactively review expenses based on a company’s expense policy and merchant details, and either make recommendations to human approvers or approve all of the in-policy expenses and only elevate questionable ones to humans. So far they can eliminate human review for 85-90% of them, and the product just launched two months ago.

These seem like small things, but if you’ve had to submit or approve expense reports, or god forbid had to chase down employees to submit receipts, you know how much time this stuff takes - both directly and indirectly, in lost focus. This is an issue for everyone, at every level, even for very expensive people.

Susan Li, Meta’s CFO, told John Collison on a recent episode of Cheeky Pint that the company is looking into ways to automate rote operational work, “and I say this as a person who is like a very expensive machine learning model for approving expenses. I'm not certain that when I approve expenses I'm really adding a lot of deep human intelligence to this process. I'm scanning for a fairly checklistable set of things. And yet I get multiple expenses every day.”

Susan Li’s reported total compensation in 2024 was $27.2 million. Assuming she works something like 70 hours per week, each hour she spends doing expenses costs the company north of $7,000. More importantly, she makes that money because she’s one of the best in the world at doing the non-expense-report-approval parts of her job. Every hour she spends doing an expense report is an hour that she is not spending on more strategic work, on decisions that could move the $2 trillion company’s market cap by tens of billions of dollars.

Then there is the strife, which we have talked about since the beginning of Ramp, caused by the finance team needing to chase down employees to submit their expenses. This is so prevalent that Ramp focused on receipt chasing in its first non-Super Bowl national TV commercial:

And as an Eagles fan, Lord knows I don’t want to pull Saquon Barkley off the field to do expense reports.

These commercials are resonating for the simple reason that Eric and Karim were right: people care a lot more about saving time than other card and expense management companies appreciated.

It is telling that Bryan Johnson, the man behind the Don’t Die movement, runs his company Blueprint on Ramp. Even the man who plans to live forever doesn’t want to waste time filing receipts.

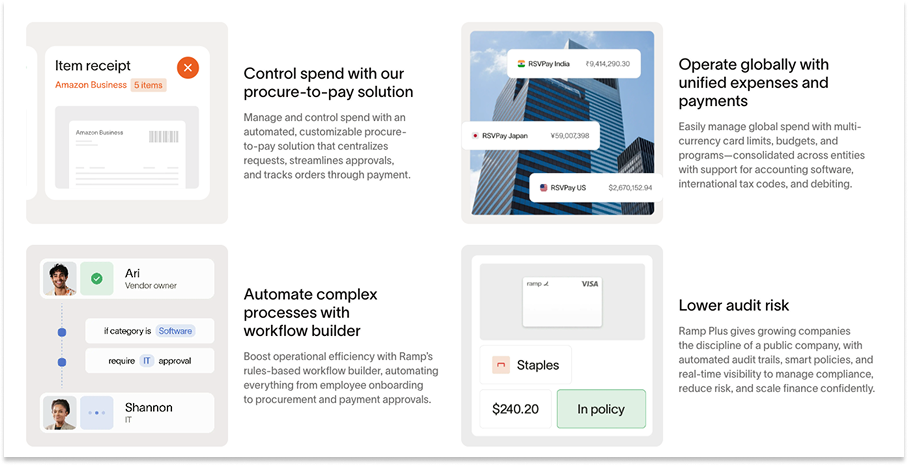

But card and expense management weren’t the only timesucks in the finance org, so next, Ramp added Bill Pay, then Procurement, then Travel, then Treasury. Ramp’s mid-market and enterprise software solution, Plus, adds more power and automation to each of these products, through traditional software features that enterprises need, and increasingly through Agents.

I’ve written about these products before, in Ramping Up, and about how building AI into their workflows will move from saving time to just doing the work, in Ramp & the AI Opportunity. I’ll tell you how those business lines are doing in the next section, but the point for now is that each one saves companies time and money, and they save even more time and money when used together.

Bill Pay can process invoices with 99% accuracy from an email forward, collect approvals, pay right from Card, Treasury, or external accounts, and sync them with your accounting software.

Travel lets employees book flights or hotels that are within policy for their specific level (the CEO might be able to fly first class, the analyst premium economy), can stop out-of-policy bookings on the Card before they ever go through, and then turn everything spent on the card during the trip into one Expense Report.

Karim told me that Ramp can take expense, AP, travel, and procurement policies from customers in whatever written form they’re in, automatically map them into the Ramp system, and start doing things like evaluating every invoice for whether it’s in-policy nearly immediately. This means that companies don’t just save time once Ramp is up and running; they start saving time during implementation.

I asked Google Gemini to “Analyze data from G2, Capterra, and implementation partner reports on the average setup and implementation time for SAP Concur, Coupa, and NetSuite versus Ramp. Express the difference in business days and required personnel,” in a fresh chat, with no mention that I was writing about Ramp. I tried to make it rough but unbiased. This is what it came back with:

The upshot is that by maniacally focusing on saving businesses time and money, Ramp has been successful in saving businesses time and money. Per the company, to date, it has saved businesses $10 billion and 27.5 million hours.

That brings us to one last thing that’s important to note, on the subject of Saving Time, which will bridge us into our second flavor, Compounding Over Time.

Those $10 billion and 27.5 million hour numbers are so large in aggregate as to be hard to pin meaning to. But they’re an aggregate of the time and money savings of many individual companies, each of which Ramp has data on, and each of which Ramp is focused on saving more time and money for.

What that data means is that Ramp can use what it’s learned to sell to new accounts and expand within existing ones.

For new accounts, by understanding how many credit cards the company would use, how much money it might spend, and how many expense reports it might submit, it can walk in the door knowing how much time and money it could save the company with just card and expense management.

Next-generation card controls that “surgically and automatically block non-compliant, out-of-policy transactions at the point of purchase, prior to payment” save customers anywhere from 3.5-8.8% in prevented spend. If you’re spending $10 million per year, that’s $350-880k saved.

Spend request workflows that decide who can spend and how much, set default limits for each employee, and approve new funds on a per-request basis reduce spend another 1.7-4.6%, for $170-460k.

Expense automations that reduce time spent on expense reports by 98% can save a company that submits 10,000 expense reports per year over 3,000 hours, or more than an employee and a half’s worth of time.

From the jump, the ROI is clear: save $500k - $1.4 million, and 1.5 employees’ time, per year.

This is true for expansion within existing accounts, too. Karim told me, because Ramp has so much data on how each of its customers spends and operates, and on how all of its customers spend and operate, its Account Managers can go to their accounts and say, “We know you process this many bills and spend this much time on procurement, but if you started using Ramp this way, or set up this feature, this is how much time you’d save. And your time is valuable, so the ROI is there.”

For a product that lands with a card, which makes money on interchange, provides software for free, and demonstrates such clear savings once it gets to work, adding other Ramp products becomes a no-brainer.

Roy Luo, a General Partner at ICONIQ, which led Ramp’s last $500 million round at a $22.5 billion valuation, told me that the resonance of this value proposition is one of the things that jumped out to him in talking to Ramp’s customers.

“I can’t tell you the number of times customers would say, ‘I can’t believe this stuff is free,” he said. “I loved Ramp because they’re an application and AI platform monetizing through a card, but the card was never really the product. It’s genius, super smart; it reduces a lot of barriers to sell and win.”

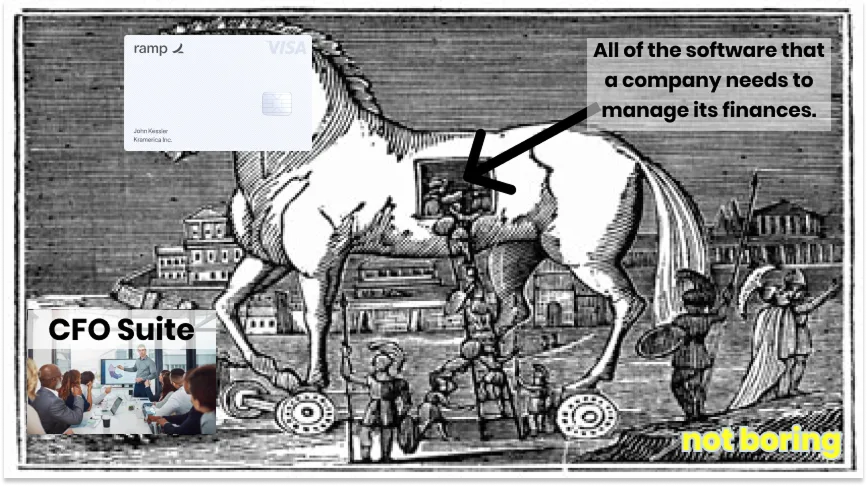

But the card is just the entry point. In my first Deep Dive on Ramp, I wrote, “The corporate card, then, is a Trojan Horse directly into a company’s finances.”

The idea that time is the new luxury, that you could build a really big business really quickly by saving companies time and money, is an excellent starting point and strong counter-positioning. But translating that idea into a web of specific products, people, go-to-market motions, and implementations is how you compound over time.

Compounding Over Time

That Ramp has grown incredibly fast to this point is not up for debate. It is growing at a speed for its scale that very few companies ever have.

But it’s hard to look at the landscape of early stage venture-backed companies today and believe that growth is invariably good, or that it will inevitably last. In many instances, although it’s never fully clear which until after the fact, investors pay high prices for growth that has already occurred, when the very pace of that growth contains the seeds of its deceleration.

This is the question that I wanted to discuss with Eric when we spoke about doing this piece: the durability of Ramp’s growth.

I come into all of these Ramp Deep Dives excited about the company. That’s why I’ve written so many of them. Ramp is a special one, and it moves so fast that I learn something new each time.

There is also a point in the process of writing each of these at which I get even more excited about the company. Something clicks. In Ramp’s Double-Unicorn Rounds, it was the company’s velocity and trajectory, the realization I opened this essay with, that if a company is growing fast enough, seemingly insane valuations soon become sane. In Ramping Up, it was that transactions are jumping off points for new applications; that, for example, when companies spend on Travel on the card, it puts Ramp in position to build a better Travel product. In Ramp & the AI Opportunity, it was that a company built to save time and money was perfectly positioned to take advantage of incorporating AI into its workflows; built well, and paired with the ability to pay, AI could just do a lot of the work.

This time, what’s clicked for me is Ramp’s unusual combination of velocity and durability, that the business is built to compound at high speeds for a long time.

What’s amazed me across these opportunities to study Ramp is just how consistent and fruitful the core idea has been, and how each passing year adds new layers and S-Curves that move in that same direction.

John Coogan, the co-host of TBPN and long-time Ramp supporter, told me that one of the most underappreciated things about Ramp is that they’ve avoided “launching slop product extensions by basically trusting how big that one core thing can be.” That means that instead of wasting energy on short-term shiny new things, Ramp can focus all of its energy in one direction, on compounding on the core.

When I asked Calvin how they’ve managed to be so consistent, he brought up a word that I’ve never heard a company use to describe itself: correctness.

“The founders and leaders and Ramp are still paranoid about quality and velocity, and also about correctness,” he said.

I asked him to tell me more, because correctness seems like something that every company just kind of automatically wants. If a value is only useful if someone else might hold the opposite value, it’s hard to imagine a company valuing incorrectness. What makes correctness practical at Ramp?

“Everyone wants to be correct, but not everyone is smart enough to be correct,” Calvin explained. “But there’s a process version of this”:

For example, there’s a bad version of move fast and break things where you just spasm. It’s important to think before you code. We have a core principle around scoping: a short but decisive process to make sure you build something that a customer actually wants to use. To waste all of that engineering time would be downright tragic. So we try to avoid those sorts of things.

Avoiding stupidity is a lot easier than seeking brilliance. We are good at calling out when things are idiotic. Karim is particularly good at this. We have a good culture of internal debate.

It comes down to having smart people who care and work hard. You can be more correct by doing more work. Also, just caring. When people are bold and wrong once, we respect it a little. But you keep it up and we’re just going to remember you were wrong.

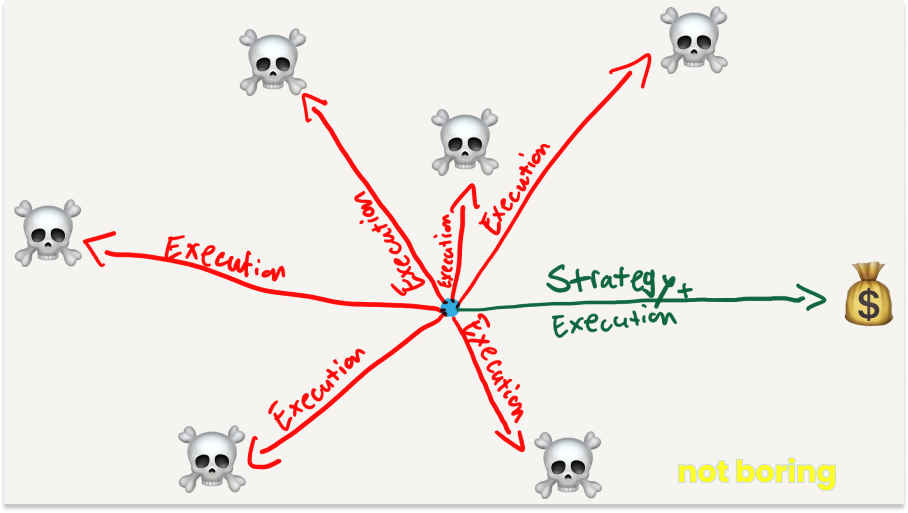

Talking to Calvin and starting to write this section, I realized that one of the reasons I’m so drawn to Ramp, and one of the reasons I keep writing about it, is that it is the perfect real-time case study of the argument I made in In Defense of Strategy.

I wrote In Defense of Strategy in July 2023, when AI companies were starting to grow really fast out of the gate, and when a sentiment started to grow alongside them: that strategy was for wimps, and that speed of execution was the only thing that mattered.

I disagreed, arguing that “companies that are the best at execution are precisely the ones for which strategy is most important. They’re the only ones that have a shot.”

“The better you are at execution,” I wrote, “the faster you can run in any direction. A good strategy helps you run fast in the right direction.”

Plenty of companies have executed their way into a good strategy - they got a bunch of smart people in a room, tried a lot of things, listened to customers, learned, and iterated towards the right strategy, against which they then executed.

That can work, although executing without a strategy means that you are forced to make a trade-off: either you can grow fast and then realize what you’ve built is not defensible, obliterating the value of your startup, or you can bounce around more slowly until you get to something that can grow fast, defensibly.

But you can’t do what Ramp has done – grow both fast and durably, from Day 1 – without both forming a clear strategy and executing against it at high velocity.

In that same Strategy essay, I tried to show why strategy - a diagnosis (there is an opening for a financial software company that helps customers save time and money), a guiding policy (“For every product we build, and everything we do, the goal is always, ‘How can we save more time for customers?’”), and coherent actions (all of the specific things Ramp does to save customers time and money) - means bigger, more durable companies, faster.

Startups have an “uncertainty window” - a period during which what they’re doing is uncertain enough that others won’t copy - which can be extended by what Hamilton Helmer calls counter-positioning, “the practice of developing your business model such that incumbents have conflicting incentives preventing them to compete effectively.” For Ramp, that was saving time and money instead of offering points and rewards.

During this uncertainty window, they can either use a limited set of coherent actions to aimlessly execute – the “bad version of move fast and break things where you just spasm” - or use them strategically, in one direction, such that they compound: “A good diagnosis and guiding policy channels and coordinates those limited actions so that they can compound on each other.”

Execution and velocity are important. By moving fast, Ramp earned more actions during its uncertainty window, and earns more actions in any given time period now that it’s moved outside of the uncertainty window. But it is the fact that these actions are coherent, guided by correctness, that lets them compound into a business that gets more durable with time.

It is unsurprising that Ramp, a company that counts the days since its founding (today is Day 2,367), understands this better than anyone.

Which is an easy claim to make, but I understand if you won’t simply believe me without the numbers.

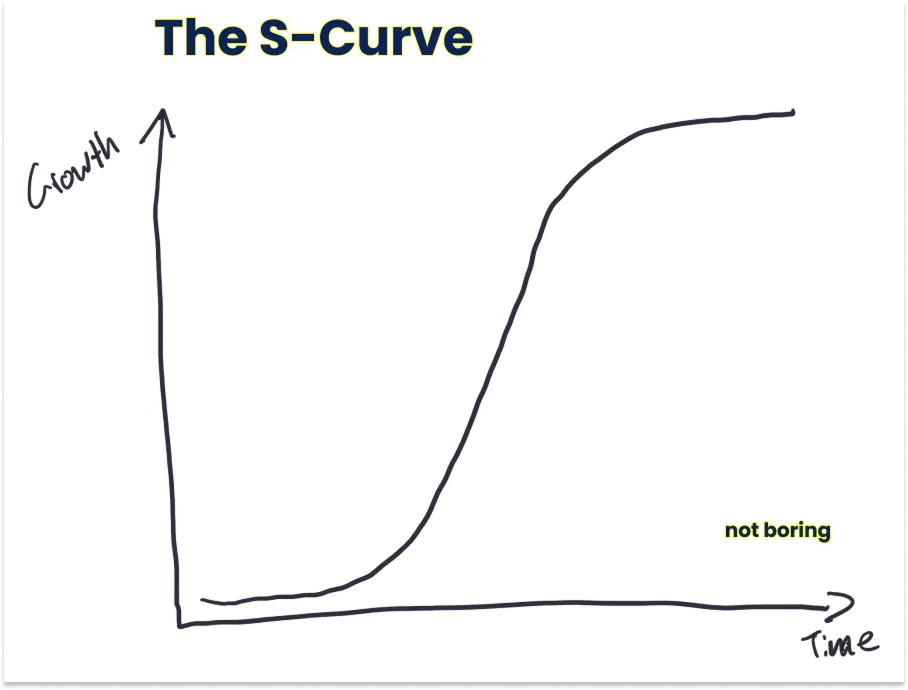

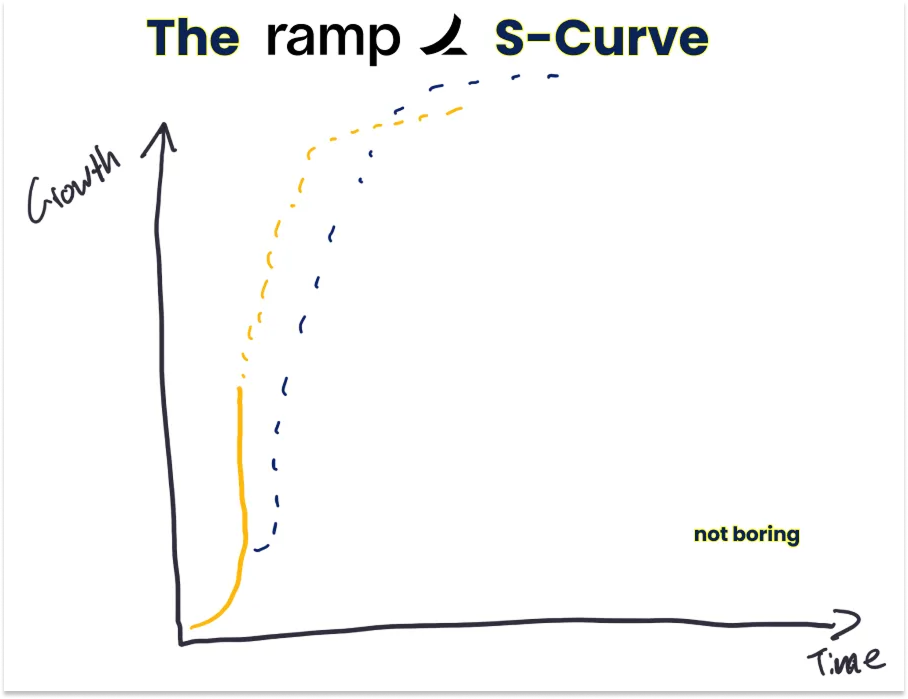

The best way to think about Ramp’s business is as a series of S-Curves, each of which compounds on the others and, because Ramp has focused on releasing core, non-slop products, each of which enhances the others.

As I wrote in Ramping Up, “A typical S-Curve describes the idea that a product’s growth normally starts slow, accelerates for a period of time, and inevitably slows down at maturity once it’s saturated the market. It looks something like this.”

Card is Ramp’s first S-Curve, and it is still in the growth phase. By picking the competitive but massive corporate card market as its first market, Ramp picked a market in which it could grow for a very long time.

As of July, Card had over 45,000 active customers and is growing through both new customers and through increased spend among existing customers. It is an impressive and compounding business in its own right.

But in that same March 2022 Deep Dive, I wrote that “as Ramp’s first major non-card product, Bill Pay has the potential to build the next S-Curve for the business.”

Bill Pay has realized that potential. It is the next S-Curve.

Roy at ICONIQ, who has studied and invested in this space for over a decade, told me that what Ramp has been able to do with Bill Pay is very rare.

“In the world of Office of the CFO tech,” he explained, “there are very few companies that have truly captured lightning in a bottle twice organically. Everyone else bought their way into the next act. But Bill Pay is very special. To have the success that product has had, you would have had to study the space for a decade to appreciate how hard it is to do this twice, organically.”

Over the past year, Bill Pay’s TPV has tripled and is now higher than Card.

Across Bill Pay and Card, Ramp is now at $100 billion in TPV, almost double where they were in March ($55 billion) and 10x higher than the $10 billion in TPV the company reached in January 2023. Put another way, in the over two years from January 2023 to March 2025, Ramp grew TPV by $40 billion. They increased TPV by more than that - $45 billion - in the past six months.

It makes sense that Bill Pay is growing faster, and getting bigger, than Card. Recall that of the greater than $40 trillion businesses in America spend, only $2.1 trillion, well under 10%, is spent on cards. Money moves through invoices.

Within Ramp specifically, Bill Pay also benefits from Ramp’s existing customer relationships. “Bill Pay and Card are both on the payables side, they’re expense related” Roy pointed out. “So there are natural synergies to the budget, wallet, people, and champions you sell into. If the guy down the hall loves the Card product, it makes selling Bill Pay more natural.”

This is one of the sneaky advantages to Coogan’s point about focusing on the core. It means you are often talking to the same buyer, who already loves the product they use with you. It means Ramp’s Account Managers already have trust when they say, “If you start using Bill Pay in this way, we can save you this many million dollars and this many hundred hours.”

That shows up in the attach rates. Bill Pay specifically is used by one in three Ramp Card customers, and that number is both beating plan and growing. Roy called Bill Pay’s attach rates “absolutely insane,” when something like 10-15% attach rates would be very good.

This is how S-Curves compound.

And Ramp keeps adding S-Curves.

Ramp Plus is a natural fit with Card and Bill Pay. It provides software that gives customers more of the functionality they need to save time and money, including many of the agentic products that Ramp is rolling out.

Launched in July 2023, Ramp Plus is newer than Card and Bill Pay, and it is growing even faster. It is an early proof point of the company’s thesis, which Eric expressed in our last Deep Dive, that being in the business of making other businesses more profitable can be very valuable.

Plus also makes Ramp’s business stronger and more diverse. It is the first Ramp product that looks like a traditional software product: recurring revenue, software gross margins.

Even newer and faster-growing are Treasury and Travel.

Treasury, launched January 2025, has already exceeded $1.5 billion in assets under management.

With Treasury, Ramp has “woven cash management into your AP workflow, so every dollar you’re not spending is earning — automatically.” The bet is that companies will want to keep at least some of their cash where they spend it, so that Ramp can maximize the time that it’s earning yield and customers can save time making money.

And Ramp can also help companies spend that money smarter.

Travel, launched in June 2024, has grown booking volume 6x YoY. Ramp monetizes this volume through commissions, like traditional online travel agencies (OTAs), with OTA-like margins.

With Procurement, as more Ramp customers spend through Ramp, it can help them spend smarter by applying what they’ve learned about what companies are paying for products, and by streamlining workflows.

On top of all of these S-Curves, Ramp is adding in agentic AI to the AI that has powered the products behind the scenes.

The goal is to understand the work being done, and have multiple agents get to work on it in parallel to get it done faster.

We will discuss this further in “Fighting Time” below, but it hints to another way that Ramp compounds: the more customers it has using more products, the better it can understand their business and the more actions it can take on the business’ behalf, which means more time and money saved. That means more revenue, contribution profit, and cash flow, and it also means stickier customers.

All told, over 50% of Ramp’s customers now use two or more Ramp products, and multi-product adoption is ramping faster, too.

This has all sorts of implications for the durability, scale, and speed of Ramp’s business.

First, and most simply, customers who use multiple products are stickier. This is true for most businesses; what makes Ramp unique is just how quickly customers adopt multiple products.

Second, if you believe Ramp’s premise that saving customers time and money creates healthier customers, then customers that use multiple Ramp products will stay in business longer and grow faster, which lowers churn and increases LTV.

Third, when customers use more products, their LTV increases, which means you can spend more to acquire them, which means you grow faster and beat point solutions.

Eric explained the logic:

Take a customer in any product category: Card and Expense Management, Bill Pay, Travel. If you think you will be able to cross-sell, then you can outspend any point solution to acquire them. It is totally rational to pay $3k to acquire a customer that a point solution can only spend $2k to acquire. That’s when the flywheel really starts getting going.

When you combine fast-growing maturing S-Curves with faster-growing new S-Curves, you can maintain high growth at scale.

“If you look at our TPV YoY growth, a year ago, we were growing 2.4x,” Eric said. “This year, we are growing 2.4x. At any point in time, we’re growing just as fast off a much larger base.”

As the business grows, its mix does, too, and the business gets stronger. At the end of 2023, less than 5% of Ramp’s run rate contribution profit (RR CP) was non-Card, at the end of 2024, roughly 20% was non-Card, and the company expects that roughly a third of RR CP will be non-Card at the end of this year.

If there’s one thing people remember from Thiel’s Zero to One, it’s that idea that “Competition is for losers.” Ramp has shown that competition can be fine; if you’re competing on the right dimension in a large enough market, it can actually be a good thing. People are familiar with cards. That makes them an easier entry point. From there, by proving that it’s able to save time and money, Ramp can expand to new products, making the business stronger as it grows.

Instead, Eric said, there are two important ideas from Zero to One, although most people focus on the first part. Since the value of a company is based on the present value of things that will happen many years in the future:

Growth is more important than most people think, even though people think growth is important.

Growth is conditioned on the durability of it.

As Thiel wrote:

The overwhelming importance of future profits is counterintuitive, even in Silicon Valley. For a company to be valuable it must grow and endure [emphasis Thiel’s], but many entrepreneurs focus only on short-term growth. They have an excuse: growth is easy to measure, but durability isn’t. Those who succumb to measurement mania obsess about weekly active user statistics, monthly revenue targets, and quarterly earnings reports. However, you can hit those numbers and still overlook deeper, harder-to-measure problems that threaten the durability of your business.

If you focus on near-term growth above all else, you miss the most important question you should be asking: will this business still be around a decade from now?

In its sixth year, Ramp is proving that it is both fast-growing and durable. That all comes back to saving time.

“On the surface, it looks like Ramp is selling money,” Eric said. “But Ramp sells time. Books that close themselves, expenses that do themselves, money that flows to higher yield. Money is a great way to make money, but it’s hard to sell. It’s better to sell time. It’s bad to have your best salesperson doing expense reports. It’s cheaper to hire Ramp to do it.”

“What’s core for Ramp is: do you love the product? If you do, and we get more of your spend, we get a natural take: store more funds, move more money, enable more software actions on it. We can monetize through software, or through your next business trip, take a little interchange and a commission.”

If Ramp saves customers time, then over time, it wins more of their business. Counterintuitively, that means that it can grow faster, and do even more for each customer, which spins the flywheel faster. This is how you build a business that compounds over time by saving customers time.

On its current trajectory, it seems that Ramp will still be around a decade from now, and that it will be a much bigger business than it is today.

But Ramp itself is growing. It has over 1,200 employees now. And while time allows for compounding, it also invites sclerosis.

In order for time to work with you, you have to fight to ensure it doesn’t work against you.

Fighting Time

There is a tension that comes with time, one that comes for all companies: time creates entropy. Companies get bigger. They hire more people. They have more to lose. So they respond with bureaucracy. More meetings. More stringent approval processes. Those things compound, too. And as a result, they get slower. They lose the thing that got them there in the first place. They become a Big Company.

This is a well-known phenomenon that, despite the fact that excellent startups with phenomenal leaders are aware of it and actively try to fight it, still comes for the best companies.

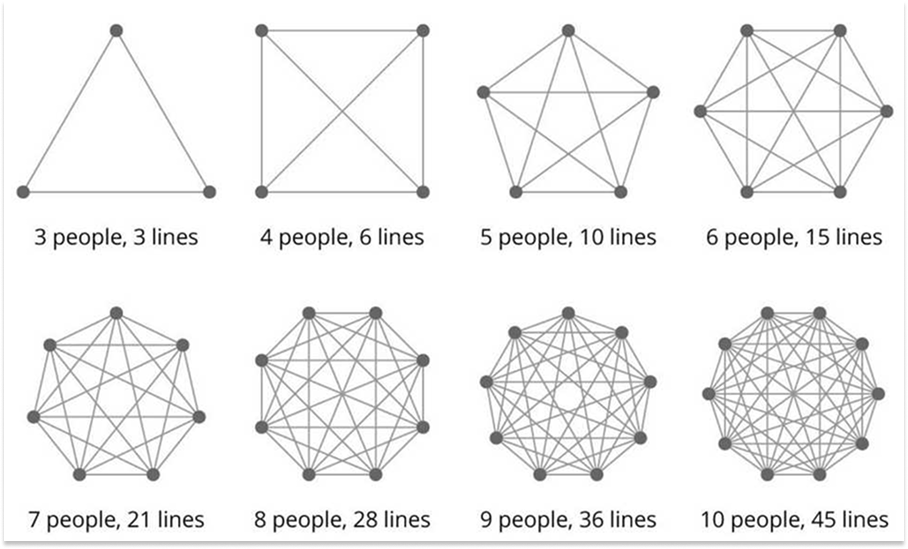

The core essay in Fred Brooks’ 1975 The Mythical Man-Month explains Brook’s Law: adding people to late software projects makes them even later, because communication overhead grows exponentially with team size. I remember Ben Nevile, Breather’s CTO, drawing these graphs with a Sharpie to demonstrate the point.

My friend Alex Komoroske made a presentation titled Coordination Headwind: How Organizations Are Like Slime Mold while working as Head of Corporate Strategy at Stripe after spending thirteen years at Google. Two companies that, at their founding, would be two of the companies you would have bet would avoid the scaling sclerosis, and yet, from the inside, he said, “This happens in every successful organization over time.”

It’s worth flipping through the 160 slide presentation (it’s quick). It shows that even with the most well-intentioned, talented, and team-oriented people, the math just works against a project’s success the bigger it gets.

That Ramp, at 1,200 people and $1 billion in annualized revenue across multiple product lines, seems to have avoided this fate thus far, then, is remarkable and worthy of study.

When you do, it actually makes a lot of sense: Ramp is entirely focused on saving companies time and money, and it applies many of the things that it does in service of that goal to Ramp itself.

There is a bit of a chicken-and-egg here: is Ramp so intensely focused on making itself more efficient because its mission is to make other companies more efficient, or do both come from the same egg, Eric and Karim’s obsession with saving time and money, first for consumers, then for businesses, and for Ramp itself?

Whichever way you resolve the paradox, Ramp wants to make an example of Ramp. In a recent company all-hands, Ramp reminded the team of a goal it set for itself in January:

And they reminded them of what that would look like:

How Ramp runs itself, then, optimistically, is a preview of what well-run companies might look like in the future, if things go right: more productive big companies behaving like small companies.

So how do they do it?

When I spoke to Karim, I asked him this question explicitly: “How do you avoid getting slow and bureaucratic as you get bigger?”

His answer was simple: “By reducing the cost of coordination as much as possible.”

Then he gave me a hypothetical example.

When you think about the procurement workflow at a lot of companies, you have this chain of jobs that needs to get done to achieve an outcome. Step 1: fill out this form. Step 2: legal review. Step 3: IT review. Etc…

The problem is that the IT person might be on vacation, or legal only finds out about the form two days later. Time is wasted because chaining is inherently slow. This rhymes with a point that Komoroske makes in Coordination Headwinds: each step in the chain reduces the project’s overall probability of success, because people are human. “But of course humans aren’t robots,” he wrote, pre-ChatGPT.

The reason, Karim said, that you don’t just run all of these processes in parallel – legal review, IT review, etc… – is that peoples’ time is very expensive. You don’t want to run an IT review on something that ends up failing legal review. It’s a waste of time and money.

But what about agents? If the marginal cost of an agent’s time is practically zero, why not just have six different agents run the process immediately and in parallel? Then, something that took weeks could take minutes. These time savings compound, too.

That was a hypothetical example. Then, he gave me three real ones.

Ramp’s product and engineering teams, which we talk about in every piece because of their absurd shipping velocity, have gotten even faster with agents. Today, Ramp’s engineers are more than 50% more productive than they were in 2024, as measured by commits per engineer.

Coding has been AI’s breakout use case in the enterprise. Just yesterday, Cognition announced a new $10.2 billion valuation. It is unsurprising that Ramp is taking advantage of engineering productivity gains.

What is more remarkable, and speaks to Ramp’s potential to make entire organizations more efficient, is that Ramp has been able to bring these efficiency gains to its entire organization.

Take marketing, which now reports into Karim. “Before I jumped into marketing,” he said, “I applied the Elon algorithm (1. Make requirements less dumb, 2. Delete the part or process, 3. Simplify and optimize, 4. Accelerate cycle time, and 5. Automate.) What are the different steps?”

Take briefs, he said. When people wanted brand or creative work, the brand team had one interface: write me a brief. They all had the same format, they were reviewed once a week by the team, and during that review, 1-2 people would decide how to allocate the team’s limited resources.

“No matter what you wanted to do in marketing, anything at all,” he recalled, “it would take a week, even if it takes less time to do the thing than write the brief.”

Say you’re on the SEO team, generating a lot of articles…

It’s crazy that you need to write a brief for each one. What if you took the process the brand team follows and turned it into software, a tool that you give to everyone in marketing, so when anyone wants to generate an image, video, colors, fonts, etc… they can do that on their own? So we built that. If something reaches a certain level of virality, great, humans can go and polish the last 20%. But basic assets are completely unblocked.

Then he gave me my favorite example, about a lunch.

A couple of months ago, Karim was trying to book a lunch for the Applied AI team. He asked his EA to set it up, and two days later, when he hadn’t heard anything, he asked what was going on. His EA said she was waiting on legal review. He asked, “Reviewing what?”

Turns out, because the booking was over a certain size, the restaurant sent over a legal contract. “It was very basic, and my mind immediately went to, ‘This is ridiculous. Why are we doing this?’”

So he worked with the legal team, and now for things like this, Ramp just auto-signs and sends an addendum to the counterparty, puts the ball back in their court. “Most people just say: this is fine, we just had to do the contract, we’re not going to argue on the details.”

This is a little example, but in a growing company, there are thousands of these little examples, and not only do they add up, they compound. If the legal team is working on the restaurant contract, they’re not working on something more important. If marketing is waiting on a brief, they’re not acquiring that next customer, wasting precious days until that customer signs up for a Card, then Bill Pay, then, with 99% probability, becomes a customer for a long time.

Technology can help. AI, specifically, can help, by doing a bunch of the routine work that a lot of people end up doing because they have to but don’t love doing, like briefs and lunch contracts, like expense reports.

But knowing where to apply AI in the first place takes people who are obsessed with this.

“I don’t know if we’d want to put this in the piece,” Calvin told me, making me really want to put it in the piece, “but Karim has a hobby of huddling the teams at 2am. When we need to get something done, Eric calls me on the weekends, and we make it happen. They still care about the outcomes; that’s the most fundamental thing.”

Ramp cares more about the outcomes than the things that big companies typically care about, like looking good to others in the industry, or doing things “the right way.” Being wrong is OK, as long as you’re wrong fast. “The secret to building great products faster,” Eric said, “is to reduce cycle time.” Diego says it well here:

In each one of these pieces, I ask Redpoint MD Logan Bartlett for his take. Normally, they’re outlandish, like “I don’t want to be quoted saying Ramp is the perfect B2B company because that’s ridiculous… but it is” or “I won’t sell for less than $200b” (although, respect).

This time, though, he was also more serious. He shared why he thinks Ramp has been able to avoid the ravages of time:

As companies get bigger, there’s more and more of a need to get things right when they ship a product. The expectations are higher than that of a start-up and so are the stakes. You have brand credibility associated with this new thing and so you want so badly to get it right because you don’t want to dilute how you’re perceived. Elements of the classic innovators dilemma.. and yet Ramp doesn’t care? Or hasn’t fallen victim to it?

They hire people who care about excellence but they’re willing to try and fail on stuff which allows them to succeed. This coupled with entrepreneurially hiring and autonomy seem to me to be the secret sauce of acting like a small disruptor at scale for Ramp.

This is why, for example, when he was already running one of the fastest-shipping product and engineering teams in tech, Karim stepped in and added marketing to his plate.

This is one of the most surprising changes since the last time I wrote about Ramp. When I was talking to Eric about sponsoring Not Boring last year, he looped in… Calvin, who I was not expecting to see on the marketing team.

Calvin was a founding engineer at Ramp, whose resumé, according to this tweet from Eric, included:

Admitted into MIT at age 16

Code running on the International Space Station

Top 20 in the country in the Putnam Math Competition

And here he was negotiating a small newsletter sponsorship deal.

When I asked Calvin what he was doing in marketing, he said that good marketing looks a lot like product building, structure-wise. “It has the same tripartite structure: Performance Marketing is Engineering, Brand Marketing is Design, and Product Marketing is… Product.”

When you put really great engineers in marketing, he continued, there’s a lot they can do.

In Ramp’s case, he said, “We have implemented AI everywhere we can: videos and good looking static content, without a drop in quality. We’ve really optimized targeting across channels. We run experiments day in and day out, with more rigor on the experimental side.”

When I asked Karim a similar question - why put engineers on marketing? - he cited “pragmatic problem solving.”

“One thing that’s really different now (with AI) is that the value of skill and subject matter expertise is now relatively lower than the value of will. It’s a lot easier to learn to do something now. If you really like an ad, you can write your new ad in the same style. Really, in marketing, we’re now a lot more focused on: you have an idea, you want to bring it to life, how do you do that as fast as possible? On the creative side, you can learn a lot from history if you’re more focused on results than on winning awards.”

One tangible outcome of this pragmatic approach is that Ramp’s marketing team is now much more focused on marketing to companies that don’t look like Ramp, the millions of non-venture-backed-fast-growing-tech-companies that drive a huge portion of the economy.

This is something that Amin at Founders Fund noted in our conversation.

“People in Silicon Valley are pretty obsessed with selling to other tech companies,” he said. “Ramp zagged, and said, ‘Let’s sell to people who don’t traditionally get this kind of love.’ Energy, education, home services, sports - areas that traditional Silicon Valley go-to-market (GTM) says, ‘Don’t focus on these areas.’”

And when Ramp goes in, Amin said, they go all-in. “Ramp has quintessential adaptability - adapt or die - where they see opportunity present itself and focus their bazooka of talent on seizing it.”

This is how, for example, Ramp made a Super Bowl ad in just seven days:

Targeting non-Silicon Valley companies means going all-in on non-Silicon Valley tactics, too.

Calvin calls this a “counterpositioning philosophy. If everyone is shifting their marketing to AI, think about the things that are going to stand out, the things that can’t be done with AI.”

Of course, Ramp’s engineering-led marketing team uses AI too, probably more heavily than most marketing teams. “Both extremes are good,” Calvin said. “Go heavy into AI, or into the things that AI will never replace.”

Targeting the non-tech market early is a way of fighting time, too. It’s an effort to get ahead of the fact that early adopters eventually dry up, that at some point, you need to cross the chasm. Ramp is leaping over it. With success in those harder-to-reach but larger markets, the compounding will continue more smoothly than it otherwise would.

All of this is true. Fighting time internally means that Ramp can continue to move fast long past the time when most companies begin to slow down. Fighting time externally - by understanding that even the most successful startups tend to briefly sputter out at $10 billion in revenue, once they’ve run out of the usual targets - means that Ramp can continue compounding far longer than most companies do.

But I think there’s something more going on here: Ramp actually just cares about saving time and money, about eliminating the bloat that weighs down companies, and weighs the economy down with them.

A few minutes after I got off my call with Karim the other day, he texted me a link to this tweet.

This is the kind of shit that drives him nuts.

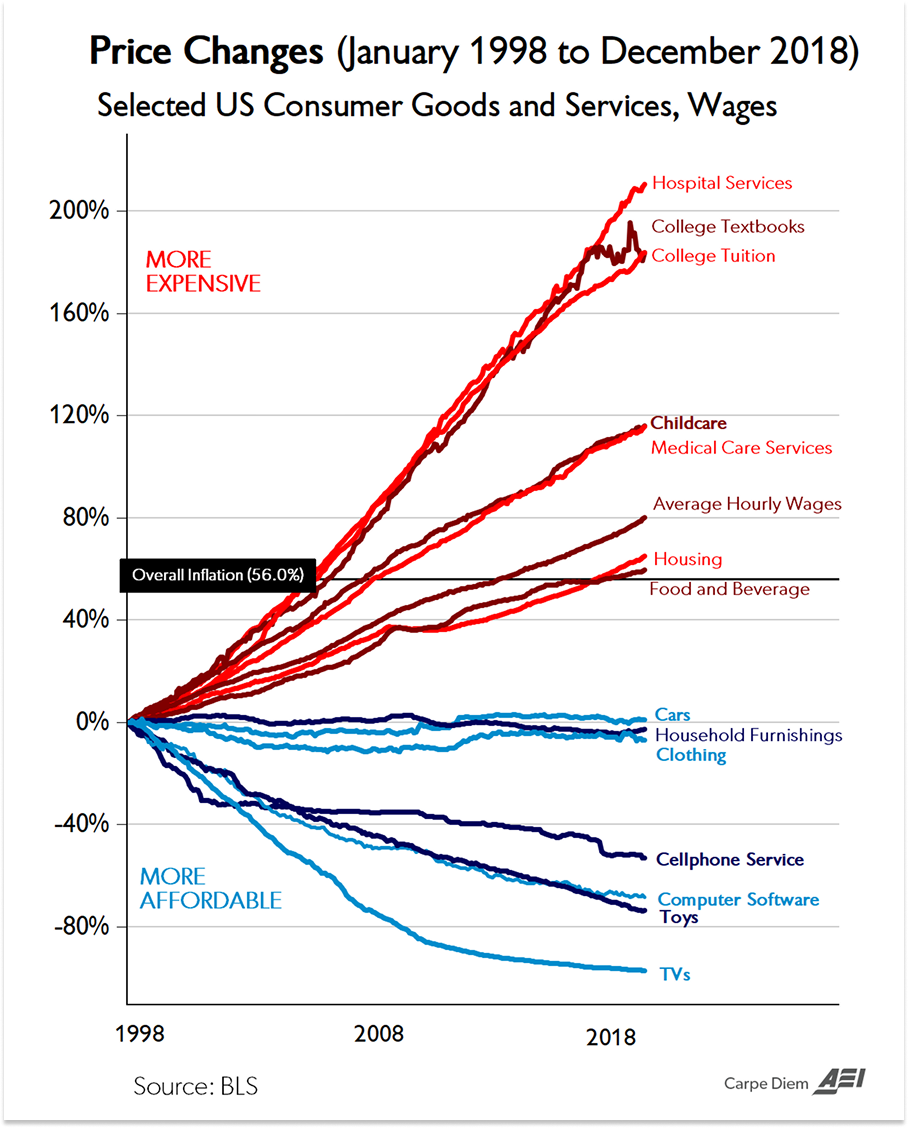

On our call, he mentioned a different but related chart, this one that’s familiar to a lot of people in tech, a symbol for the idea that anything on which tech is allowed to work its magic gets cheaper over time, while every industry that lets bureaucracy win gets more and more expensive.

The chart he texted me afterwards was the “why.”

“Education and healthcare outcomes haven’t gotten better in the past twenty years. What are we spending on?” he asked. And answered: “Very little money is going to educators and doctors, but a lot is going to administrative bullshit.”

This is what time does, left to its own devices. It makes organizations grow. And as they grow, their coordination costs grow exponentially, and suddenly, the number of administrators in the healthcare system has grown 30x more than the number of physicians. More people to do more work created by having more people, ad infinitum. It is clearly unsustainable.

“This is really where we’re applying a lot of our expertise and product building,” Karim said. “How do we get 80-90% of the bullshit work to go down so that organizations can do the thing that they exist to do?”

Ramp, then, is a laboratory for the change that it wants to prosecute across the economy, from Silicon Valley to Dallas, Texas, in all of the big cities and small towns where bloat drags us down.

“I don’t think Ramp is going to shrink as a company,” he said. “We will just be able to do a lot more, faster. It won’t take another 140 years to build AmEx. We can do it faster, with fewer people, doing more than AmEx is able to do.”

Similarly, applying tools like Ramp, he believes, “won’t make organizations not want to grow; but it will make the productivity of each additional person a lot higher.”

If Ramp can keep fighting time within Ramp and winning, the plan is to ship products at high velocity to help all of the other companies, and the whole economy, fight time and win, too.

A Matter of Time

Financial success compounds. We have seen that throughout this Deep Dive. It is how we started the Deep Dive. Two companies, growing at different rates, end up in vastly different places over time. Ramp is a real-time case study.

I think the gap is even wider than it appears, and that that will become evident in the months and years ahead.

The reason is that capabilities compound, too. Ramp has built, and continues to build, a suite of products that save customers time and money. It is the company’s founding bet, its raison d’etre.

And now, as it incorporates AI into more and more of its products, it is in the right place and right time to save companies so much time and money that it would be fiduciarily irresponsible not to use Ramp.

One reason is obvious: if Ramp continues to save companies more time and more money, not using Ramp is like lighting time and money on fire. It’s even worse if your competitors are using Ramp. Ramp wants to do to them what it’s doing to itself: using software and talented people to make them incredibly productive at any scale.

The other reason is less obvious, and it has to do with the nature of time.

Time, Einstein tells us, is not absolute. It is relative.

Time was a different thing in the 1980s. On a Saturday morning in the ‘80s, no one could call you. Time was different even five years ago.

“Most businesses don’t have real-time visibility into their finances,” Karim told me, when I asked him when it will become ridiculously irresponsible for companies not to use Ramp. They’ve been OK waiting for month-end close to understand their financials. “They’ve gotten away with it because the world moved a little more slowly. A view of finances that’s a month or two old has been fine, because it’s taken three to six months to change something anyway.”

“Now,” he said, “the world is moving faster and faster. Switching costs are going down. Coordination costs are going down. If your business moves like a massive cruise ship, that was fine in the old world. It’s not anymore.”

“If you want a real-time, to-the-minute view of your finances, the only way to do that is by using Ramp, and generating live balance sheets and cash flow statements.”

That sounds like exactly the type of thing a co-founder of a company would say about his company’s product, but it’s also how he’s running his own company. Karim is as paranoid about this stuff as he believes others should be.

I asked the other people I spoke with a similar question: when does it become irresponsible not to use Ramp?

There are things that the company needs to build.

Calvin pointed to improvements coming in procurement for non-tech businesses.

Eric said that Ramp will need to keep expanding internationally. “Ramp works basically everywhere. We have more than eighty countries with Ramp cardholders, and every month people are spending with Ramp in every country except sanctioned ones,” he said. “We’ve started issuing cards in other currencies, and we’re onboarding Canadian companies.”

To serve multinational companies, and uninational companies in the world’s many markets, to begin to add to its near-zero international market share, it will need to grow its footprint as rapidly as its product suite.

But, maybe predictably at this point in the Deep Dive, the most common answer I heard is that it’s already a no-brainer; that actually doing the legwork to sign up all of the customers who could benefit from switching to Ramp, many of whom are under long contracts with other card companies, will just take time.

“One enterprise wanted to sign a fifteen year agreement with us,” Eric said, “which leads me to believe that they’re used to fifteen year agreements with other companies. Some of our adoption will just come from waiting for those fifteen year agreements to expire.”

“The biggest thing we’re fighting right now,” he said, “is inertia. Our win rate in head-to-head deals when a customer makes a switch is high. When we lose, it’s most often due to a ‘no decision’ or ‘seems cool, we’ll come back when we’re ready to switch.’”

Ramp needs to grow awareness. More direct mailers, events, TV ads, Deep Dives, and, most importantly, word-of-mouth. These things take time.

Ramp still isn’t in every conversation when large companies are thinking about going with the brands they’ve used forever, like AmEx and Chase. But for newer vintages, the percentage of companies talking to Ramp is growing.

“If you win 20% of new cohorts, it might not look obvious to people how much of this is happening,” Eric said. “It takes years to show up.”

All of which is to say, at this point in Ramp’s journey, getting really big, doing $1 billion of revenue in a month, and then in a week, and then maybe even faster, is just a matter of time.

Job’s not finished.

Thanks to Eric, Karim, Calvin, Lindsay, Fax, Will, Amin, Logan, Roy, John, and the Ramp team for your time and insights.

That’s all for today. We’ll be back in your inbox on Friday with a Weekly Dose.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

B2B company list consists of ~100 public companies in the Meritech Software index. Ramp, Crowdstrike and Snowflake using run-rate revenue; Applovin using both LTM revenue and FY revenue from publicly available financials, with FF extrapolation. Criteria for inclusion on page - crossing both $500M and $1B revenue thresholds with at least 70% y/y growth rate, with minimum 25% revenue CAGR from 2022-2025E (to control for anomalous Covid growth pull-forward)

Pissed I’m a retail investor. I would’ve invested in Ramp back in 2023, when I was writing up a $BILL short and discovered them.

Sorry it It took me so long to get to reading this my backlog was a bit insane.

Packy, I love these Ramp Deep Dives. They are so powerful. I think there's something really important about revisiting an amazing growth company and telling its story chapter by chapter. Amazing lessons in here, if everyone will take the "time" to read them.