Welcome to the 2,104 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 39,996 (so close!) smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen here or on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Secureframe

Secureframe helps companies get enterprise ready by streamlining SOC 2 and ISO 27001 compliance. Secureframe allows companies to get compliant within weeks, rather than months and monitors 40+ services, including AWS, GCP, and Azure.

Whether you’re an enterprise or a small startup, if you want to sell into enterprises, you’re going to need to be compliant. Secureframe makes the process faster and easier, saving their customers an average of 50% on audit costs and hundreds of hours of time.

Secureframe’s team of compliance experts and auditors are happy to help answer any questions and give you an overview of SOC 2 or ISO 27001, even if you don't need it today. Schedule a demo and learn how:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

Today’s post is one that I’ve been wanting to write for a while, made timely by some big funding news last week. It’s Fantasy M&A Time.

So throw on Epidemic hit Faster Car:

And let’s get to it.

Soundtrack the World

(You can click on ☝️ to go straight to the full post online)

Back in April 2019, a recruiter reached out to me about a role I might be interested in: Managing Director, North America at Epidemic Sound. I’d never heard about Epidemic before. It was a fast-growing Swedish music company, but not that fast-growing Swedish music company. But I was itching to leave Breather and I decided to take the interview. After an hour in the office, I was sold.

Epidemic Sound’s mission is to “soundtrack the world.” It commissions artists to make music, which it licenses royalty-free to content creators who want to avoid dealing with all of the messiness of music labels and Performing Rights Organizations (PROs). The team was sharp, passionate, strategically savvy, well-read, and Swedish. The company had patiently grown for ten years and was beginning to bring its two ecosystems -- creators and musicians -- together in powerful ways. It was a dream job.

I didn’t get it. Epidemic went with Spotify’s former Australia Head, Kate Vale. Told you they were smart; that was very obviously the right call.

In July 2019, Epidemic raised $20 million at a $370 million valuation. Last week, Epidemic announced a massive $450 million raise at a $1.4 billion valuation from Blackstone and EQT, a solid 12x increase from the reported €100 million valuation at the time of my interview.

After I left the first day of interviews, my first thought was, “Spotify needs to buy this company.” The time wasn’t right then, though. Now, even at a 12x higher price tag, I think it is.

Spotify is coming off of a phenomenal year. It’s stock price has more than doubled year-over-year. It’s rolling out new features and products at a rapid clip. Its podcast Streaming Ad Insertion is showing early signs of working. And it’s charging labels to get their artists’ songs heard by more listeners. At 40% music streaming market share, the labels need to play ball with Spotify.

In late February, it hosted its “Stream On” event and Analyst Q&A. Without explicitly saying it, Spotify is slowly increasing its power over the record labels to whom it pays out the majority of its revenue. Things are going well for Spotify, but that arrangement is a thorn in Spotify’s side. It depresses margins.

Spotify backward integrated into supply via podcasts, and it should do it again in the core of its business, music streaming, by acquiring Epidemic Sound. That’s right, it’s Fantasy M&A time. I’ll tell you a little about Spotify, a little about Epidemic, and then walk through the rationale of a merger.

Spotify’s Problem with Labels

Spotify Streams On

Enter Epidemic Sound

Spotify x Epidemic

The logic for the deal starts with Spotify’s long-standing problem with labels.

Spotify’s Problem with Labels

Spotify changed the music industry by working with the music industry.

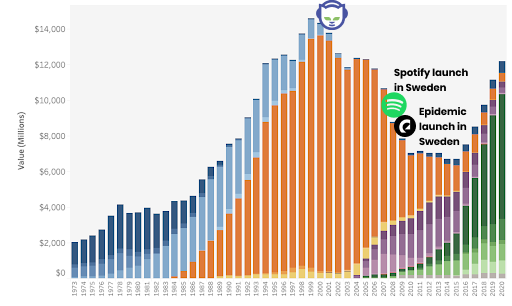

In 2001, Napster let people download songs for free, which predictably crushed sales. From a 1999 peak of $14.6 billion, the US music industry shrank to $11.8 billion by the time Daniel Ek founded Spotify in 2006, and another $3 billion to $8.8 billion by the time it launched in Sweden in 2008.

The music industry sued Napster into oblivion, but the genie was out of the bottle. Spotify wrangled the entropy Napster created, and more broadly that a new form of digital distribution made inevitable. Spotify worked with the labels, and listeners could pay one monthly subscription fee (or listen to some ads) to access most of the world’s music in one easy-to-use interface. That came with a cost for Spotify -- they had to pay the labels the majority of the revenue they brought in through subscriptions and ads.

Music labels, the biggest of which are Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group, do a few important things for artists: A&R Support and Funding, Marketing and Promotion, Distribution, and Admin. Until recently, making a high-quality recording of a song required expensive studio time, sound engineers, and producers. Getting that song out to people required expensive distribution and the right relationships with radio stations, record stores, or Digital Service Providers (DSP) like Spotify, Apple Music, or Tidal. All of that cost money, which most new musicians don’t have.

So they sign with labels. The label pays the artist upfront (an advance) and pays for all of the upfront costs of making, marketing, and distributing an album or song. In exchange, they get paid first when the artists start making money. After the labels recoup their costs, they pay the artist a percentage of revenue on an ongoing basis. Artists generally make 13-20% of ongoing revenue from major labels that paid them an advance, and can make up to 50% with smaller indie labels that don’t pay advances.

Labels have traditionally made the most money in the music value chain. To see why, let’s look at an example. Take an artist who signed with a major record label, and assume they’ve paid back the advance and upfront costs and receive 15% of streaming royalties.

For simplicity, let’s say Spotify makes $10 billion total, and this artist’s songs make up 0.1% of all streams (meaning its share of revenue is $10 million), and that Spotify pays out 70% of revenue to the labels (in range with reality).

Here’s how the payments flow from the $10 million attributable to the artist:

Spotify pays out $7 million and keeps $3 million (30% gross margin)

The Label makes $5.95 million of the $7 million (85%)

The Artist makes $1.05 million of the $7 million (15%)

Plus, the labels own the valuable back catalogs (unless they sell them off to an investor; see Taylor Swift v. Scooter Braun). That gives them massive leverage over Spotify and the artists. If Spotify wants the songs that its listeners want to listen to, it needs to work with the labels.

In Earshare: The Idiot’s Guide to Investing in Spotify, I wrote about the predicament that Spotify was in coming into 2020:

In its current state, it is essentially a marketplace business with little leverage over the supply side, the labels who own the valuable back-catalogs of music that the demand-side of the marketplace demands. Spotify pays about 70% of subscription revenues out to the labels for the right to stream their artists’ music...

Adding to the complexity, as part of its early licensing deals, Spotify gave 18% of its equity to the record labels. Most of the labels have sold off their stakes, but Universal Music Group still owns roughly 3.5% of the company. If it sells, it will split the money with its artists.

For most of Spotify’s life, it’s been in a weird spot with the labels: it, along with other DSPs, have been largely responsible for saving the music industry, but the labels still hold most of the power, and therefore, most of the economics.

Even as the music industry has recovered on the back of streaming -- according to Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, global music industry revenue was at $17 billion in 2008, when Spotify launched, hit a nadir of $14 billion in 2014, and rebounded to $20 billion in 2019, $11.4 billion of which came from streaming -- Spotify’s gross margins remained flat at around 25% thanks to payouts to labels.

In 2019 and 2020, Spotify began an aggressive push to take leverage back from the labels by investing heavily in audio content the labels couldn’t touch: podcasts.

Between February 2019 and November 2020, Spotify spent $1 billion to acquire podcast technology and content, not including exclusive deals with Michelle and Barack Obama, Kim Kardashian, DC Comics, and others, the terms of which were not disclosed.

Spotify’s strategy here -- backward integration -- is not new in streaming. Netflix is the poster child there. For the first 16 years of its life, Netflix did deals with studios for non-exclusive rights to their content. Then, in 2013, it successfully released its first major original show, House of Cards, the rights for which it paid $100 million. That year, Netflix spent a total of $2.4 billion on original content. This year, Netflix is expected to spend $19 billion. The more Netflix spends on original content, the better its margins get. In 2012, its gross margins were 26.5%. According to Atom Finance, its gross margins are expected to hit 43.3% this year.

Most people agree that Spotify’s push into podcasts is an attempt to do something similar: the higher proportion of time Spotify listeners spend on podcasts versus music, the less of its revenue it has to pay labels. This is quasi-true for now; while the details aren’t public, podcasts might not impact the amount of money Spotify pays labels under current agreements, but more podcast time means more leverage for Spotify in the next round of negotiations.

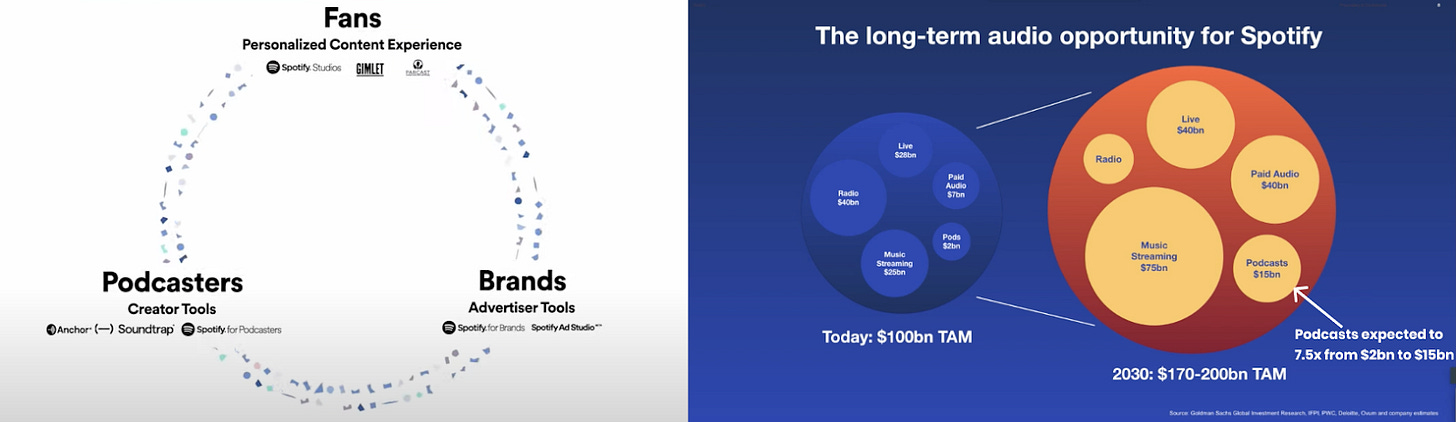

Podcasts are big and growing. Spotify isn’t just stealing share from market-leader Apple in podcasting; it’s stealing from radio and expanding the podcast ad market. Spotify thinks it can grow podcasting into a $15 billion industry. To start, it’s bringing podcasting up to par with other ad formats through Streaming Ad Insertion, first in its original & exclusive podcasts, and next, thanks to its Megaphone acquisition, to any podcast via the recently announced Spotify Audience Network.

The market clearly understands and appreciates the argument. When I wrote about Spotify last March, it was trading at $137. A year later, it’s more than doubled to $279.

Not everyone is convinced, though. In January, Citi put a sell rating on the stock, citing no material benefit in app downloads or gross Premium subscriptions from the podcast push.

In my humble opinion, Citi is looking at it the wrong way: the move isn’t about short-term download numbers or Premium subscription sales; it’s about:

Shifting earshare from nearly 100% label-dependent music to a mix of music and podcasting,

Slowly diversifying the revenue mix,

Proving it can build businesses without middlemen,

Building up leverage,

And ultimately, using that leverage to improve margins.

As I wrote last March, Ek has always been focused on winning audio long-term. He fully expects podcasts to become an increasingly important part of that mix, and is investing accordingly, but music will always be the key. Spotify expects streaming music to be a $75 billion market by 2030, 5x the size of podcasts. If Spotify is to achieve its 30-40% long-term gross margin target, it’s going to need to fight the labels on their home turf.

Spotify Streams On

Spotify’s stated mission is, “To unlock the potential of human creativity by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art, and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it.”

Its externally-unspoken business mission is to build as much leverage over the music labels as humanly and algorithmically possible, and one day cut them out for everything except their back catalogs. It’s finally getting the scale it needs to act.

In 2014, Spotify was a small fry. Pandora led the nascent music streaming market with a 31% share; Spotify came in fourth at 6%. By 2019, Pandora was effectively dead at 2%, and Spotify sat alone atop the leaderboard at 36% market share, twice Apple Music’s. During its Stream On event, it pegged its own share at 40%.

Labels can certainly hurt Spotify by pulling their catalogs, but now, Spotify can inflict even more damage on labels if it chooses to. For now, it’s mutually assured destruction, but it’s becoming less mutual, and Spotify’s destruction less assured, by the day.

On the surface, Spotify is a friendly company. Its whole Stream On event was a celebration of the artists, songwriters, and podcasters who have built lives on top of the platform. Ek never came out and said, “We need you less and less, labels.” But Spotify is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and if you watch the event closely enough, you’ll see veiled threats everywhere.

Ek opened the event with a speech in which he talked about the state of the industry when Spotify was born (not good) and how streaming saved the day:

Over the past decade and a half, what we’ve seen and helped drive is an audio renaissance. And I use that word intentionally. It really is a renaissance, and what it is not is a restoration. We’re moving forward, not turning the clock back. People love to look back fondly on the music industry two decades ago, the era of the record store and the FM radio, a time before piracy. And I understand the nostalgia, I get it…. But what really strikes me is how limiting it was...

Case in point, back in 2002, just over 30,000 albums were released in the U.S., and only 8,000 sold more than 1,000 copies, representing 98% of sales of new releases. By comparison, in 2020, 1.8 million albums were released on Spotify in the U.S., and six times as many albums represented 98% of the streams for these releases. So it's not just the possibility that more artists can be heard by a global audience, it is that more artists are being heard.

Ek’s opening remarks, and the full event, are worth watching in their entirety.

Ek spoke softly and almost sweetly, but he sent a message to the labels: “We’re never going back to the world you dominated. Your power is waning.” It’s clear in the numbers: there are 60x more new albums and 6x as many successful albums today than there were 20 years ago. The easier it is to release an album, and the more successful artists there are, the less power middlemen have.

Over the next 100 minutes, Spotify dropped subtle clues about the labels’ diminishing power. Today, Spotify is the unquestioned audio aggregator, which allows it to do all of the things that labels can do, at scale, more cheaply.

Recall what a label does: A&R Support and Funding, Marketing and Promotion, Distribution, and Admin. Spotify quietly flexed its capabilities in each area throughout the event (we’re going to ignore Admin - Spotify has dashboards and payments).

A&R Support and Funding

Charleton Lamb on Spotify’s Marketplace Team talked up the capabilities of Soundtrap, a 2017 Spotify acquisition that gives creators a collaborative recording studio in the cloud, and the ability to find any person you’d need to produce a high-quality song via the marketplace. Recording doesn’t need to be expensive, and a marketplace for talent replaces gatekeepers who “know a guy.”

The role of A&R as tastemaker is weakening, too. Popular artist Khalid talked about his experience uploading Location to Spotify, getting picked up by the Mellow Bars playlist, and rocketing from 8k monthly listeners to half a million to 24 million to the #1 most-streamed artist on Spotify. Location now has over 1 billion streams. Khalid signed with RCA Records -- the label is not yet obsolete -- but he surely did so on better terms than he would have without Spotify.

Marketing and Promotion

The balance of power is clearly shifting in Spotify’s favor here, as evidenced by the fact that labels are now paying Spotify for better placement and a better chance at inclusion in playlists. Everything with enough eyeballs eventually becomes an advertising business.

Additionally, Spotify’s RADAR program finds and supports up-and-coming artists from around the globe with marketing and editorial support. Spotify takes out billboards to promote artists on its platform, and lets artists promote ticket sales and merch through Spotify. Increasingly, Spotify is part of any new album’s marketing plan, and artists are even adjusting songs to fit Spotify’s model.

Plus, as Matthew Ball wrote, Spotify has the data to market better than the artists or labels themselves:

Spotify and Apple Music have not just the majority of an artists’ fans on their platforms, but also the greatest insight into these fans. No one can do a better job of reaching Beyoncé fans than Spotify — including Beyoncé. And it costs the company nothing to reach them.

Distribution

Music distribution is digital now. Getting played on the radio is less and less important, and record stores are practically non-existent. Spotify playlists are the new record store shelves. As Spotify pointed out time and again, getting on the right playlist can make an artist’s career.

Playlist inclusion is based on a combination of algorithms and human editorial that Spotify’s Chief R&D Officer Gustav Söderström called “Algotorial.” With 8 million creators creating more than 70 million tracks, 4.5 billion playlists, and 2 million podcasts, all of which can be mixed and matched to create personalized experiences for Spotify’s 345 million listeners, labels aren’t as well-suited for modern distribution as Spotify itself is.

But they can pay for it. In an overt example of the shift in power, Spotify highlighted Marquee, which lets artists’ teams pay to sponsor music recommendations. Marquee gives songs an extra boost with the algorithm, but doesn’t guarantee inclusion. Now, if labels want to give their artists the best shot at getting listens, they can pay Spotify directly.

Increasingly, these tools are becoming self-serve. Spotify for Artists lets artists and their team submit pitches to Spotify’s playlist editors for inclusion, and Marquee is opening up a self-serve platform after being restricted to a small test pool. The more democratized these tools, the more power Spotify has over the labels.

Alec Benjamin, whose Let Me Down Slowlyhas 766 million streams, said, “I can either sign a record deal or do this by myself. That’s not a choice I would have had before.” Lauv, the I Like Me Better artist with over 1 billion streams on Spotify, put it more bluntly than Spotify’s team could itself: “To be able to do that without having to sign to a major label, to be able to fund the operation internally, is so sick.”

Spotify is the aggregator in audio. Increasingly, it’s where the listeners are, which means that talented artists can find an audience with or without a label. As Ek explains the flywheel:

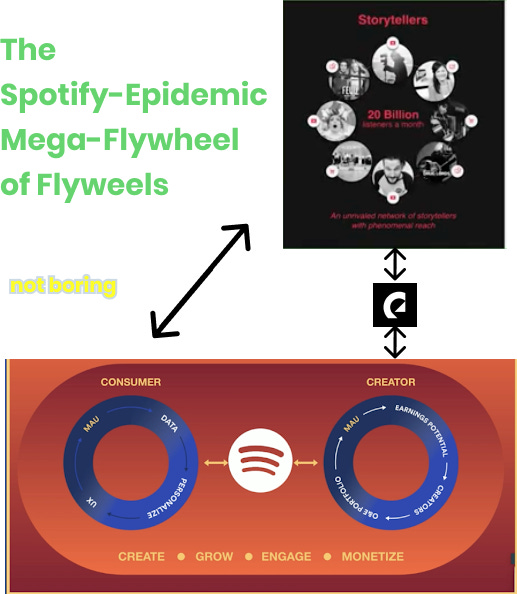

A more connected, more engaged community of listeners creates more demand, and more opportunities for artists and podcasters to make a living, and the more people creating, the more there is for people to discover. It's a virtuous cycle, a flywheel.

Presenting to analysts in a Q&A after the event, he shared this graphic:

Spotify changed the way music is distributed and consumed, and it’s slowly but surely making the labels less important, but its flywheels tell only half of the modern music distribution story.

Enter Epidemic Sound

Epidemic Sound’s mission is to soundtrack the world. It commissions music from artists, and licenses it royalty-and-headache free for content creators to use in the stories they tell.

Spotify is B2C Music, Epidemic is B2B and B2B2C Music. Spotify directly connects Creators and Consumers, Epidemic Sound connects Storytellers and Musicians. Spotify is a subscription marketplace, Epidemic is a SaaS business.

Spotify changed the music industry by working with the music industry. Epidemic Sound decided to skip that and build its own “completely new music industry.”

Remember how an artist typically gets paid when their song streams on Spotify from earlier? It’s complex, but things get so much messier when the artist’s song is embedded in a YouTube or TikTok video, played in the background of a movie or TV show, or piped into your favorite store.

Licensing a song for use in an online video, movie, or store was historically a nightmare. Labels owned the rights to songs, and Performing Rights Organizations (PROs) enforced royalty collections for every play, which was a huge headache for everyone involved. I have a friend who worked on a digital streaming platform that shut down, and a year after they closed up shop, the last thing they were still dealing with were music royalty claims.

Epidemic Sound launched in Sweden in 2009 to make the whole process dead simple.

The company started small, commissioning tracks and licensing them to Swedish TV and commercial producers. One night, the story goes, co-founder and CEO Oscar Höglund was sitting at home flipping through channels, and heard Epidemic’s music on each and every one. They were ready to scale.

To do that, they identified their two customers: Storytellers and Musicians.

For Storytellers, who were used to dealing with all sorts of licensing and royalty headaches, they set out to make the process as simple as possible. As Höglund describes it:

We built a completely new music industry from scratch. We didn’t invite the PROs and we didn’t invite the labels, and they were furious. We re-engineered how you produce music. We re-engineered the product, the business model, and we got rid of everything that was tied to reporting.

One monthly fee gave Storytellers the right to a catalog of tracks and sound effects, all rights included, without ever having to worry about royalties again. They turned a confusing variable cost into a straightforward fixed cost, and attracted movie and TV producers, Netflix (they soundtracked Narcos), YouTubers like PewDiePie and thousands more, Multi-Channel Networks (MCNs, groups of YouTube channels), ad agencies, podcasters, Twitch streamers, commercial producers, and more. They even worked with restaurant and store chains to provide royalty-free music to pipe into physical locations.

For Musicians, they turned variable and unpredictable revenue into a clear upfront payment. Epidemic commissioned tracks with certain attributes, and interested artists could accept the gigs and create based on clear parameters. Before Li Jin popularized the idea of the Creator Economy Middle Class, Epidemic made it possible for musicians to earn a living somewhere between playing shows every night and making it big. An artist might get paid $5,000 per track, directly from Epidemic, with no label in the middle.

Epidemic built two networks, Storytellers and Musicians, and then something happened. As Höglund told an audience in 2018: “the network effects started giving network effects on top of each other.” As Storytellers’ videos took off on YouTube, TikTok, Twitch, and more, commenters started asking, “What’s that song?!”

Epidemic decided to lean in, streamed the songs to Spotify and other DSPs, and posted links in the comments. They drove thousands, then millions of streams, which brought in “a shitload of money.” This is what got me so excited about the business when I interviewed.

Because they owned the rights, they could do what they wanted with the money, so they decided to split streaming revenue 50/50 with Musicians (recall that most major labels pay 13-20%). That meant Musicians had both a comfortable floor and a high ceiling, which attracted more Musicians, which meant better music, which attracted more Storytellers, which meant more money. The flywheel was spinning.

Even better, Storytellers pay Epidemic to do their distribution for them! That’s massive. Marketing and distribution is the labels’ biggest cost, and Epidemic gets it better than free. When Storytellers’ videos succeed, Epidemic succeeds with them.

At the time Höglund described the dual flywheels in 2018, he said Epidemic’s songs were getting played 20 billion times per month. Last week, when TechCrunch announced Epidemic’s unicorn round, they wrote, “YouTube videos using music from Epidemic Sound artists are played 1.5 billion times each day,” not including plays across TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, Twitch, podcasts, on TV, in stores, or on Spotify itself. That’s 45 billion plays per month on YouTube alone across Epidemic’s library of 32,000 tracks.

Epidemic Sound’s songs are sneaky popular on Spotify, too. In 2017, the music industry got very angry with Spotify for putting so many “fake” Epidemic songs in its playlists. Music Business Worldwide wrote an article called, “WHY SPOTIFY’S FAKE ARTISTS PROBLEM IS AN EPIDEMIC. LITERALLY.” The problem, as one music label exec explained it, is that by including Epidemic’s tracks in playlists, Spotify was “watering down our beer.” Since it pays out royalties based on a percentage of overall plays, the argument went, Spotify was able to pay label-backed artists less by pumping more Epidemic streams into the pool.

Epidemic pushed back and said that there was nothing fake about the songs. They were popular on YouTube so Epidemic uploaded them to Spotify, they became popular, got picked up in playlists, and got more popular. Spotify paid out royalties to Epidemic just like they would to a traditional label.

But it makes you think, if the criticisms had been right: more Epidemic songs, lower royalty payments to the labels, higher margins. That sounds like Spotify’s unspoken business goal -- lower label dependency and improve margins -- doesn’t it?

Fantasy M&A: Spotify x Epidemic Sound

Spotify and Epidemic have made sense as a pair for a long time. Some of the reasons are obvious and a little on the nose:

They’re both Swedish (Sweden is a music tech powerhouse), and share investors.

Epidemic’s songs are very popular on Spotify already -- I’ve been listening to Epidemic’s playlists while writing this, and I’ve recognized a ton of songs from other playlists.

The two companies have complementary databases and algorithms that could be used not only to build better recommendations for listeners, but also better recommendations for Musicians. Spotify/Epidemic could reduce the risk in making music, at scale.

Epidemic’s mission has always been to “Soundtrack the Internet.” Look what Spotify says on its Investor Relations page:

Those are all bonuses. There are two main reasons Spotify should acquire Epidemic: acquiring Epidemic would help Spotify solve its biggest challenge, and double down on its biggest strength.

Solving Spotify’s Biggest Challenge

Spotify’s biggest challenge is its margin profile. It’s essentially a subscription marketplace business with flat gross margins dictated by the labels. It gets very little operating leverage with scale - every time a song is played, ~70% goes to the label, whether it’s the only song or the 100 billionth song played that month.

That’s the reason that it’s worth only $53 billion as the world’s most popular audio company, and why its Enterprise Value / Revenue ratio is only 5.5x compared to Netflix’s 9.5x. That’s why it’s spent so much money to backward integrate in podcasting, where it has the high upfront cost, low marginal cost structure that makes tech investors go gaga.

Epidemic Sound, on the other hand, is a high-margin SaaS business. It pays for music upfront, and millions of Storytellers pay Epidemic every month for access to an ever-expanding catalog of tracks. That’s operating leverage. As I wrote in one of my first ever essays, The Rise of the Natively Integrated Company:

They took principal risk from the outset in order to better control the product and produce outsized margins. They leveraged the quality and ease of their product to attract demand, used that demand to build more quality supply, and used that supply strategically expanding into new verticals. Epidemic Sound is a Natively Integrated Company.

By acquiring Epidemic Sound, Spotify would backward integrate into owning supply, improve its margins, and own a platform on top of which it could build its own modern label.

To hit its long-term goal of 30-40% gross margins, it’s going to need to keep a much bigger portion of music streaming revenue. Assuming that music streaming is a 5x bigger market than podcasting in 2030, as Spotify does, it would be impossible to get to 40% gross margins on the back of podcasting alone. For years, people have suggested that Spotify might start its own label one day to get there; acquiring Epidemic does that in one fell swoop.

The time wasn’t right before. Spotify hasn’t had enough power over the labels to do it. It does now, as it cheerily threatened throughout Stream On.

Had Spotify tried to acquire Epidemic when I interviewed in 2019, the labels could have pulled their artists’ music in protest; today, I don’t think they could. Instead, labels will continue to work with Spotify on their back catalogs and biggest stars, while Spotify and Epidemic could create a new type of label that puts more money in smaller artists’ pockets by replacing much of what a label does manually with software.

Doubling Down on Spotify’s Biggest Strength

Spotify’s biggest strength is that it is the single biggest distribution channel for artists. It’s the audio aggregator. Spotify and its playlists are half of the modern music distribution playbook.

The other half is discovery through Storytellers. The youths don’t find new music on the radio; they find new music on TikTok, YouTube, Snap, and Twitch. Acquiring Epidemic would let Spotify leverage Epidemic’s Storyteller distribution machine.

Artists who sign with Spotify / Epidemic could easily get their songs played across YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Twitch, and other video platforms. As virtual worlds become more abundant, and AR takes off, there will be limitless opportunities for soundtracking, which mean limitless opportunities to drive traffic back to Spotify. Today, Spotify can’t play in that space with its own music, because it doesn’t have its own music. A Spotify / Epidemic label could.

This is where the two companies’ sets of flywheels could interact to create an unrivaled marketing and distribution machine:

Just as Snap has Bitmoji as its Trojan Horse into other platforms, Spotify’s original & exclusive music could be its Trojan horse into the world’s streaming videos, video games, and physical locations. It would give Spotify full 360 ownership of modern music distribution and marketing. Beautifully, what today is the label’s biggest cost would actually become a profit center for Spotify. That’s impossible to compete with.

If done right, Spotify and Epidemic could truly Soundtrack the World. The combined company would generate absurd margins, build an unrivaled distribution machine, and put more money, more reliably in musicians’ pockets.

The history of the modern internet isn’t about rebuilding old models online; it’s about fundamentally reshaping the way industries work. Typically, that’s meant cutting out the middleman. Music labels, which got hit by the internet hardest and first, have actually held on the longest because back catalogs of music are the most valuable back catalogs in media and entertainment. There’s no substitute for the Beatles.

But the fact remains that today’s new artists don’t need labels nearly as much as new artists did a couple of decades ago. Artists have the talent, brand, and direct connection with fans. Spotify and Epidemic bring the A&R, distribution, and marketing. The artists and the Aggregators make the money, the middle gets cut out. It’s a shining example of Power to the Person.

Ek was right. This is an audio renaissance; there’s no going back.

Thanks to my brother Dan for editing. Go follow him on Twitter for NYC love.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

No newsletter Thursday - see you next week!

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Great post. What are the Spotify economics like for artists when they are using the self-serve tools and not working with a label?

Hi Packy,

First of all, I love the content you're putting out. I've been following you for some time and you remain my most exciting read of the week!

I've been having problems with the email version though. I normally forward all my blogs to Instapaper to avoid inbox clutter and have all my reading in one location, but your posts are often too long for Instapaper. Do you know if there is a way to get around this?

Thanks,

Henry