Power in the Age of Intelligence

Or, strategy for those who plan to benefit from abundance

Welcome to the 737 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 258,985 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Wednesday!

Émile Borel once said that given enough time, a bunch of monkeys banging on typewriters would come up with Shakespeare. And yet, despite the innumerable X Articles on software moats in the face of AI, I haven’t read a single one that’s satisfying.

I think it’s because thinking about software moats, how a software company might protect itself from abundant code, is the wrong frame altogether, and that the more interesting and relevant frame is which companies, SaaS, hardware, or otherwise, stand to benefit the most from newly abundant inputs.

Those companies, not vibe coders, are the ones that point solutions should be worried about. They will win enormous market shares and fortunes. They will come to dominate large industries by using new technology to compete, capturing the High Ground, and expanding further outward than companies with lesser technological tools could have ever dreamed of. They will be the Standard Oils of this era.

This essay is about those companies.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Silicon Valley Bank

In 2025, crypto returned to the financial mainstream. It is, as they say, so back.

What’s ahead for 2026? I’m glad you asked. Silicon Valley Bank is out with their annual crypto outlook, featuring proprietary insights and data from over 500+ crypto clients. We love a bank that banks crypto.

Silicon Valley Bank makes five predictions for the year ahead, including:

Institutional capital goes vertical with increased VC investment and corporate adoption.

M&A posts another banner year after the highest-ever deal count in 2025.

Real-World Asset (RWA) tokenization goes mainstream on prediction market strength.

Last year, Silicon Valley Bank predicted that stablecoins would be the big breakout use case. That was correct. They think that will continue this year, too. Read their take on what comes next, free:

Power in the Age of Intelligence

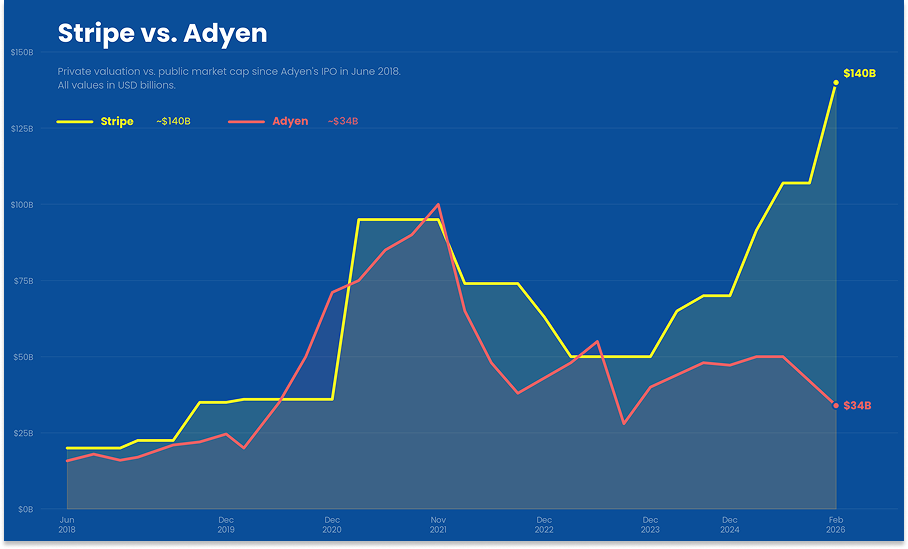

One of the more head-scratching anomalies in the market is the valuation gap between Stripe and Adyen. The two payments companies handle similar amounts of Total Payment Volume. Stripe is growing faster. Adyen reports exceptional margins and cash conversion. Stripe is reportedly doing a tender offer at a $140 billion valuation in the private markets. Adyen is valued at $34 billion in the public markets. There are a number of theories for why this is the case, most of which boil down to: VCs are idiots, as they’ll find out if Stripe ever goes public.

Ramp versus Brex is another example of the same idea. Ramp was most recently valued at $32 billion in the private markets. Brex, which had been valued at $12 billion in the private markets, sold to Capital One for $5.15 billion. Ramp is doing more revenue and growing faster, but not 6x more revenue or 6x faster. Once again, the actual market disagrees with the VCs.

Or does it?

I have a different theory, one that neatly fits those two cases, the SaaSpocalypse, SpaceX’s $1.25 trillion valuation, and even the evolving structure of venture capital itself: winner takes more.

The history of business is basically the history of increasing concentration of value, accelerated in spurts by technological change. Centuries ago, firms operated within cart-hauling distance of their customers, creating a system of local monopolies. A brewer in 1800 served a single town, if that. Canning, railroads, telegraphs, mass production, electrification, containerization, planes, and the internet, among other technologies, expanded companies’ available market, and winners captured a greater and greater share of value.

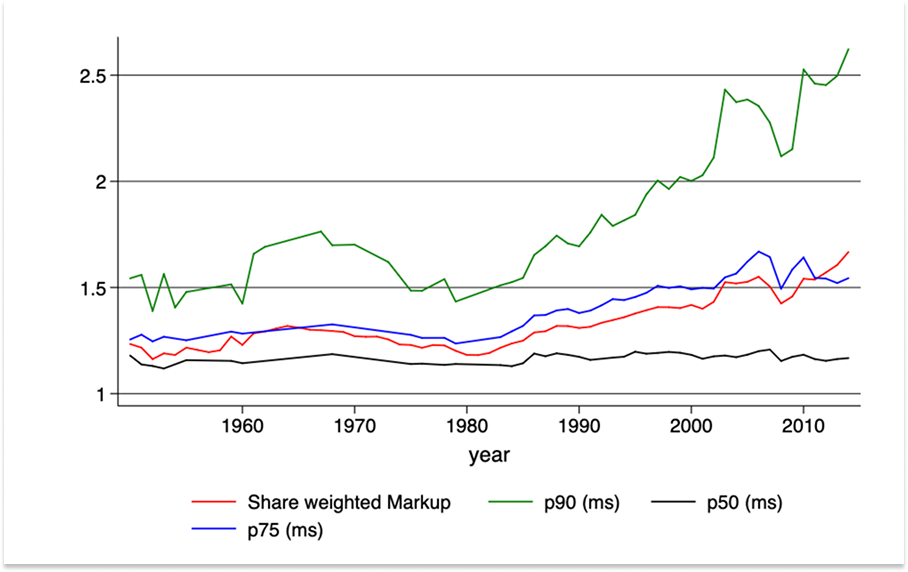

Economic data backs this up.

In a 2020 paper, Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout found that aggregate markups rose from 21% above marginal cost to 61% between 1980 and the late 2010s, and this increase was driven almost entirely by the upper tail of the distribution; median firm markups barely changed, while the 90th-percentile markups surged.

In The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms, Autor et al. find that industry sales concentration trends up over time across measures, and it rises more in sales than in employment, what Brynjolfsson et al. call “scale without mass.” In their account, this shift reflects reallocation toward superstar firms with high markups and profits and low labor shares.

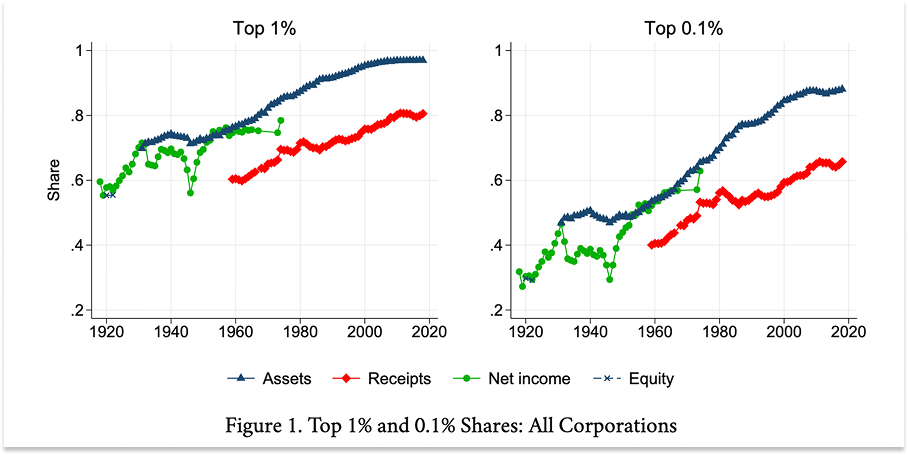

A 2023 paper by Spencer Y. Kwon, Yueran Ma, and Kaspar Zimmermann at UChicago, 100 Years of Rising Corporate Concentration, uses IRS Statistics of Income to show that the top 1% of U.S. corporations by assets accounted for about 72% of total corporate assets in the 1930s and about 97% in the 2010s. The top 0.1% of U.S. corporations by assets increased its share of total corporate assets from 47% to 88% over the same period. Power laws within power laws.

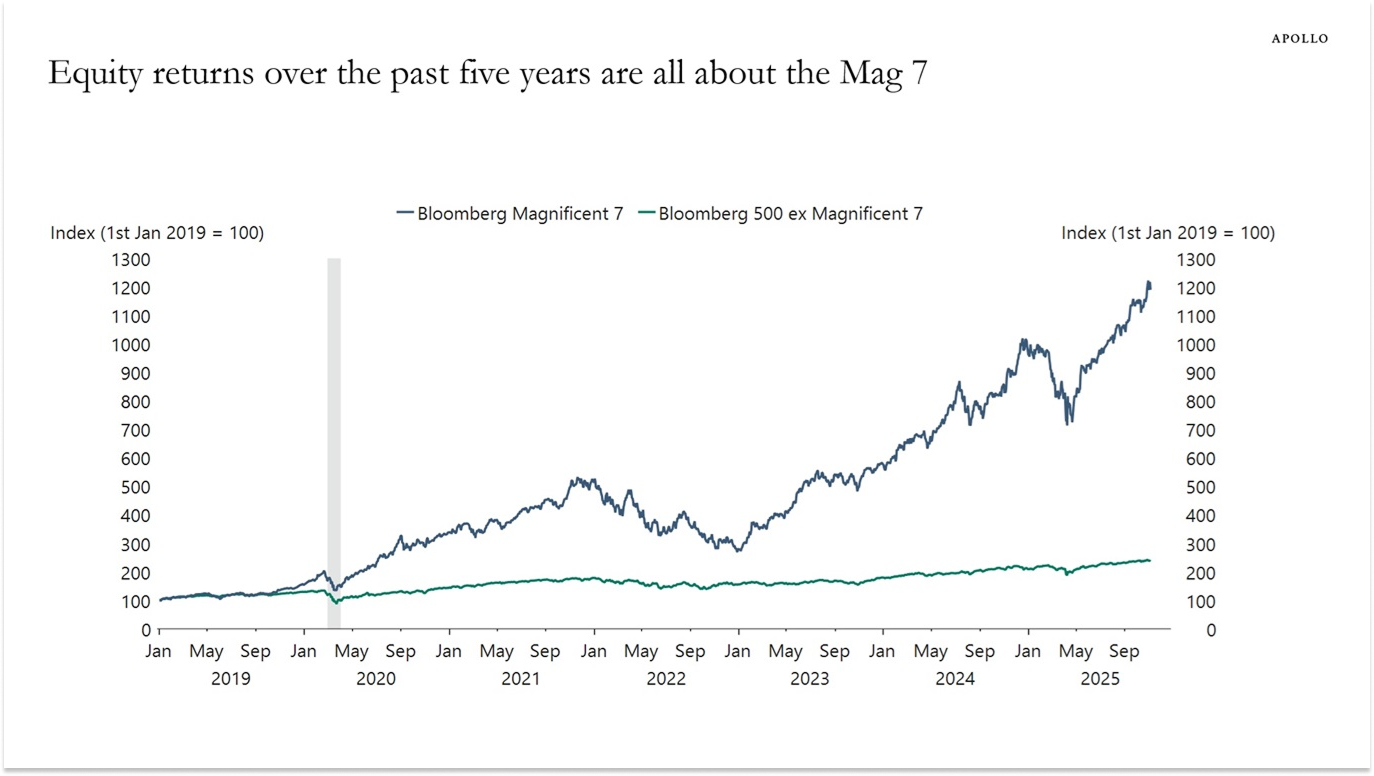

Today, the Magnificent 7 accounts for one-third of the market cap of the S&P 500, and Apollo showed that those seven companies are driving the vast majority of equity returns.

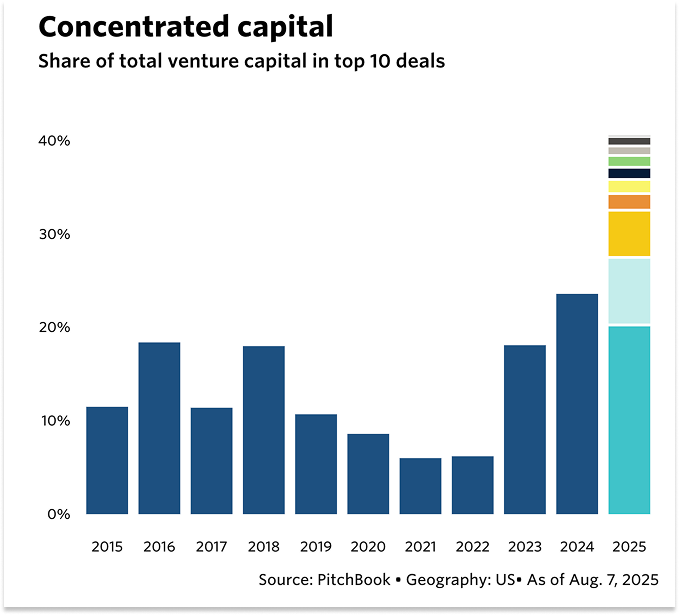

Venture capital is responding to this information as you would expect. Per Pitchbook, as of August last year, 41% of all VC dollars deployed in the US in 2025 went to just ten companies. Per Axios, more recent Pitchbook data shows that “The estimated aggregate valuation of unicorns hasn’t actually changed too much — $4.4 trillion vs. $4.7 trillion at the end of 2025 — because the top 10 companies account for around 52% of value (up from only 18.5% in 2022 and the highest such figure in a decade).”

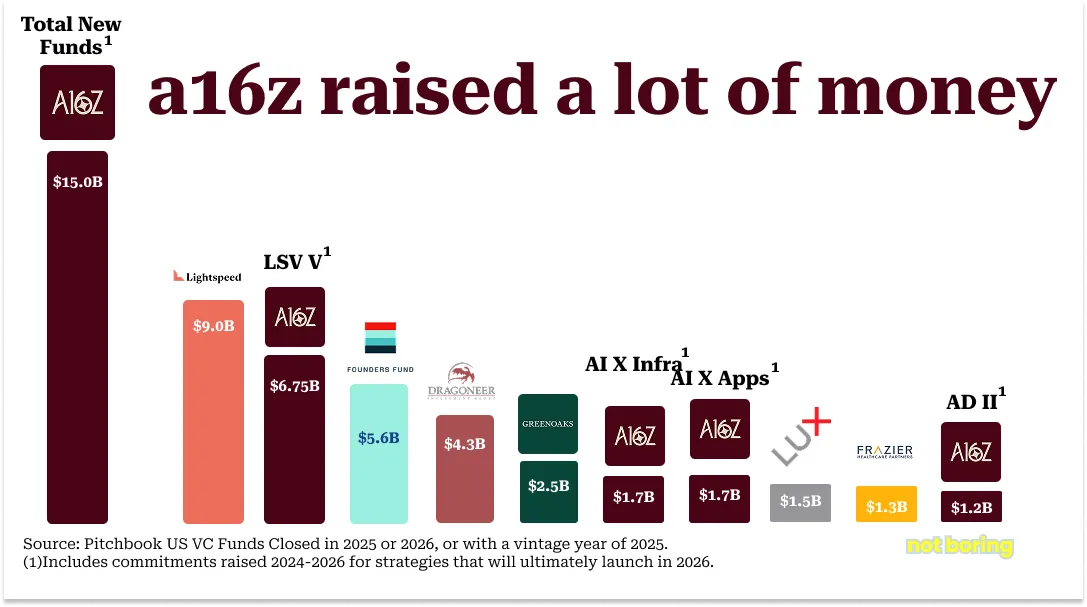

Venture capital firms themselves are concentrating. As I wrote in a16z: The Power Brokers, “a16z accounted for over 18% of all US VC funds raised in 2025.” Just yesterday, Thrive announced that it raised $10 billion: $1 billion for early-stage investments, and $9 billion for late-stage investments, which is the kind of split you put in place if you believe your winners are going to keep winning.

The theory for investing in very large funds like a16z, Founders Fund, Thrive, General Catalyst, and Greenoaks is that they are best positioned to win large allocations in the handful of companies that matter, and that those companies will capture most of the value in this vintage. Notably, all five of the firms I just mentioned are investors in Stripe, and three of the five (Founders Fund, Thrive, and General Catalyst) are investors in Ramp.

All of that data suggests increasing concentration. Through this lens, the SaaSpocalypse (the violent sell-off in software stocks) is less about software writ large dying, and more about point solution software finally facing economic gravity. They are no longer getting a free pass simply for having a good business model.

The past few decades of software exceptionalism have been an exception based on a business model so sweet and capabilities so universally useful that the rules of strategy, while not wholly unimportant, were less consequential than normal. A venture capitalist could look at a standard set of SaaS metrics (ARR, growth rate, net retention rate, gross margin, LTV:CAC, Rule of 40, etc…) and underwrite whatever new business they encountered to them. This is why you hear things like “Here’s how much ARR you need to raise a Series A.” The companies are basically all the different flavors of the same thing.

There are, of course, idiosyncrasies between selling software to professional services firms and selling software to energy companies, for example, but the basic model is the same. Invest upfront to hire engineers, write software to make someone’s job easier, and sell the software to as many customers as possible at high margins. Different industries may need software to do different things, have different buyers, be larger or smaller, be more or less willing to pay, and be more or less expensive to acquire. A bigger, less crowded market with a strong need and a high willingness to pay is better than the opposite. But figuring that out is relatively straightforward. Since software operates at the edge of value in most industries, and does not attempt to strike at its core or compete with it, it doesn’t require thorough competitive analysis.

Since the SaaSpocalypse, people have gotten AI to write tens of thousands of words on which types of software companies have moats given AI and posted the resulting essays to X. They’ve gotten a little more specific than “SaaS is good.” Data is a moat, or a particular type of data at least. Or it isn’t, maybe, because The Agent Will Eat Your System of Record. Certainly, dealing with regulatory hair earns you a moat. No?

Most of the takes I’ve seen miss what matters.

On paper, Stripe and Adyen have basically the same moats, as do Ramp and Brex. I love a good hardware moat more than the next guy, as I’ve been writing since The Good Thing About Hard Things in July 2022, before ChatGPT or Claude Code but when it was clear that good software alone would offer no moat. I was too unspecific in that piece, too. Some hardware businesses will get very large, and others will fail. Hardware itself isn’t a moat. Good luck making LFP cells in America.

No, what matters is becoming the leader in your industry in a way that is incredibly specific to that industry and in such a way that your business benefits from, instead of being threatened by, abundant improvements in general purpose technologies like AI and batteries.

What matters now is the same stuff that has always mattered but that software forgave for a while: own the scarce, defensible asset in an industry and use it as the High Ground from which to dominate. Ricardo said this.

If you’re a startup, and you don’t already own the scarce asset, then you need to identify the constraint holding the industry back, focus everything on breaking it, and expand from there.

History’s most influential military strategist, Carl von Clausewitz, said this. He called it Schwerpunkt, the center of gravity. “The first task, then, in planning for a war is to identify the enemy’s center of gravity, and if possible trace it back to a single one,” he wrote in On War. “The second task is to ensure that the forces to be used against that point are concentrated for a main offensive.”

For our purposes, the Schwerpunkt is the constraint you attack. The High Ground is the scarce and valuable position you win by breaking it. Moats are what keep others from taking it.

Even while forces must be concentrated against the Schwerpunkt, our attackers must plan for victory before it is won. The company that breaks the constraint needs to build the complementary assets (the distribution, the manufacturing, the customer relationships) to capture the value from its own innovation. Otherwise, its competitors will.

David Teece argued this in 1986, in Profiting from Technological Innovation. The paper, he wrote, “Demonstrates that when imitation is easy, markets don’t work well, and the profits from innovation may accrue to the owners of certain complementary assets, rather than to the developers of the intellectual property. This speaks to the need, in certain cases, for the innovating firm to establish a prior position in these complementary assets.” Which is the point I am making: innovation alone, software or hardware, isn’t enough.

Figuring out which companies might capture the Schwerpunkt and use it as a High Ground from which to expand is an entirely different kind of underwriting, impossible to do in a spreadsheet alone, even with Claude in Excel.

Companies that don’t own the High Ground face existential risk from technological progress. If you’re just selling point solution software, then software abundance is a threat. Hardware isn’t necessarily the moat people think it is, either, even if it’s less susceptible to AI, because AI isn’t the only technology improving rapidly. “Hardware is a moat” is the same kind of lazy thinking that “SaaS is the greatest business of all time” is. If you’re selling better mouse traps, you’re at risk every time someone builds a slightly better mouse trap.

Similarly, incumbents that currently own the High Ground but can’t wield modern technology face existential risk from those who can. This is why there is such a large opportunity for startups today. New technologies mean old constraints are finally attackable, and it’s likely to be newer companies doing the attacking.

Companies that do own the High Ground, on the other hand, and are tech-native, benefit from technological progress, just as land owners captured the gains from more farming labor and better farming tools, but more pronounced, because these modern landowners will corner the best talent, the most capital, and the richest veins of distribution. A glib way to put it is that a Ramp engineer with an AI will build something better than a CFO with an AI, no matter how good the AI gets. It’s not the vibe coders you should be worried about.

Newly abundant resources can have opposite effects on your business depending on your position, and it is likely to be the company with the High Ground wielding those resources that dooms the companies in weaker positions. Ask Slack how it felt to compete with Microsoft Teams; companies like Microsoft can now build a lot more “Teams.”

The game on the field is all about understanding who can own the High Ground in a given industry.

The moats are the same as they’ve always been. Study 7 Powers. When you’re starting out, you need to understand what your moats might be, but in order for moats to matter, you need to have something worth protecting. You need to own the High Ground.

If we really are living through the most consequential technology revolution in history, why are you spending so much time hand-wringing about protecting small, old castles when you could be thinking about how to build history’s most magnificent businesses?

The abundant inputs keep getting cheaper. The scarce asset keeps getting more valuable. The companies that own the latter and leverage the former will become larger than ever before.

These businesses themselves are scarce assets, valued on their strategic importance and industry size, because the opportunity is no longer to sell software into industries in order to marginally improve them, but to win those industries and capture their economics.

If your aim is to build or invest in these companies, old heuristics will do you no good. You need a brain of your own, some sweat on your brow, and some good ol’ fashioned strategy frameworks to help you reason about the opportunity at hand.

This essay is a guide to thinking through where power might concentrate, for those willing to think. If winner takes more, it’s about what it takes to build, or invest in, the companies that have a shot at winning large industries. And it’s about how to position yourself to gain strength from technological progress instead of running from it while throwing weak “moats” in your wake.

It is about Power in the Age of Intelligence.

A Tale of Two Industrial Revolutions

Or, it’s about Power in any age of rapid technological change, really.

While the advances we are experiencing today feel unprecedented, my thesis has been that we are going through a modern version of the Industrial Revolution.

Then, machines did what only human muscles could previously. Now, machines are doing what only human brains could previously, in new bodies built to house those brains. This is The Techno-Industrial Revolution.

So it is useful to study Rockefeller, Carnegie, Swift, and Ford. None created an industry from scratch. They all fit this pattern: identify the Schwerpunkt in an existing industry, break it, seize High Ground, integrate outward, dominate.

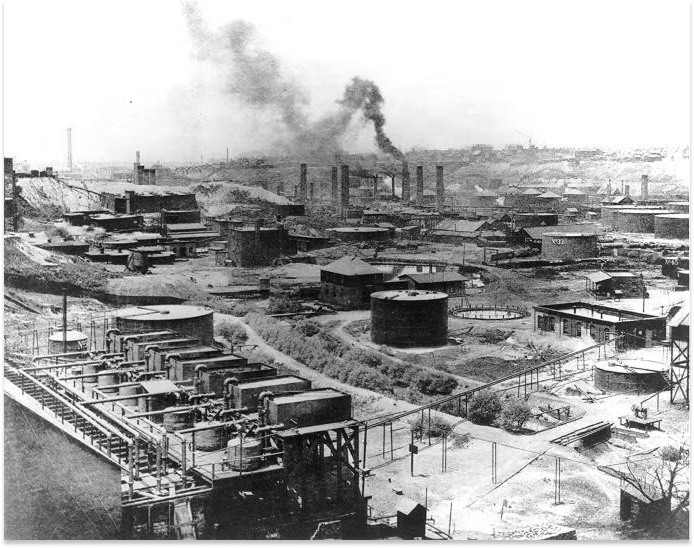

Standard Oil

When John D. Rockefeller met the oil industry, it was young, valuable, and incredibly volatile. Oil itself was abundant. There were a lot of refineries – roughly 30 in his hometown of Cleveland alone when he got to work – but their quality was inconsistent, and their processes were inefficient. Per Austin Vernon, “Refining methods were so inefficient in the mid-1860s that a barrel of oil (42 gallons) sold for almost the same price as a gallon of refined kerosene. Today, the price ratio of refined products to crude oil is ~1.25x instead of 42x.”

There was one big constraint to the profitable growth of the oil industry – the volatility – which could only be broken through scale and control. To get to scale and control, Rockefeller needed to drive down costs to capture the market. Refining was the place to get scale, given its inefficiency and the fact that, per Vernon, “A typical rule of thumb in chemical engineering is that capital costs increase sublinearly with capacity, usually by (capacity ratio)^0.6. A plant with double the output is only 50% more expensive to build, and operating costs tend to follow similar trends.”

So in partnership with chemist Samuel Andrews, one of the first people to distill kerosene from oil, Rockefeller continued to improve the kerosene yield. At the same time, he aggressively grew revenue and lowered costs by eating the whole cow, so to speak. He sold the non-kerosene byproducts others threw out (paraffin wax, naphtha, and gasoline) and used some of the fuel oil to power his own plants. He also integrated into barrels (by buying an oak tree forest and a barrel-making shop).

As it lowered costs and delivered a more consistent product, Rockefeller’s refinery (the predecessor to Standard Oil) grew, and as it grew, it lowered costs. Vernon again:

Standard Oil and its predecessor firms increased production ~20x between 1865 and the end of 1872, meaning their costs could have fallen more than 85%. At that point, they were the largest refiner in the world with a double-digit share of capacity, and it was their game to lose. If we understand this short period, then we know how the company eventually won.

The company that would become Standard Oil won the High Ground by breaking the constraint. Then it integrated outward, horizontally and vertically.

By 1870, Standard Oil was a joint stock company capitalized with $1 million that owned 10% of the oil trade in the United States. Rockefeller got busy acquiring struggling refineries or putting them out of business, increasing scale and efficiency in the process. Rockefeller also did favorable deals with the railroads, which Vernon argues actually had less to do with Standard Oil’s success than did its growing scale and efficiency. He kept growing, acquiring refiners in Pennsylvania, New York, and New England. He vertically integrated into pipelines (which replaced railroads), into distribution, into retail (ExxonMobil and Chevron are Standard successors), and into production itself.

By the late 1880s, Standard Oil controlled 90% of American refining, a share it held until it was broken up in 1911, when its $1.1 billion market cap represented 6.6% of the entire US stock market. To hear Vernon explain it, the outcome was a fait accompli by the time he’d attacked the Schwerpunkt and gained the High Ground in the 1860s.

Carnegie Steel

Andrew Carnegie’s story is so similar it’s almost suspicious. Like Rockefeller, Carnegie didn’t invent his product (steel); Bessemer did. Like Rockefeller, Carnegie realized the constraint to steel’s growth was inefficiency and inconsistency. Like Rockefeller, Carnegie hired a chemist (in his case, to measure what was happening inside the furnaces) and obsessed over cost, which he knew was the only thing he could control:

Show me your cost sheets. It is more interesting to know how well and how cheaply you have done this thing than how much money you have made, because the one is a temporary result, due possibly to special conditions of trade, but the other means a permanency that will go on with the works as long as they last.

His chemical knowledge allowed Carnegie to run his furnaces hotter and longer than anyone else, producing more steel at lower cost. His cost obsession lowered costs further. Low cost, high quality steel was the High Ground.

And from there, he integrated outward. Backward into coke (Frick) and iron ore (the Mesabi Range), into railroads to transport raw materials, and forward into finished products. He certainly didn’t sell his services and know-how to incumbents; he used them to destroy competitors on price until US Steel bought him out for $480 million in 1901 (roughly $18 billion today) to create the first billion-dollar corporation in history.

“Congratulations, Mr. Carnegie,” JP Morgan told him upon closing, “you are now the richest man in the world.”

Swift Meats

Gustavus Swift, like Rockefeller, would also “eat the whole cow.” He just did it later in his arc, and more literally.

The constraint was this: only about 60% of a live animal’s mass is edible, and meat goes bad. Which meant that, prior to the 1870s, the meat industry shipped 1,000 pound live cattle by rail from wherever they were raised to wherever they were going to be eaten. They paid by the pound (an extra 40%), had to feed animals to keep them alive and healthy, and lost some to death in transit anyway.

So Swift, building on early experiments by Detroiter George Hammond, hired an engineer to design him a refrigerated railcar. Then, he could slaughter the beef in Chicago and ship the cuts to their final table much more efficiently. Railroads, not wanting to lose livestock shipping cash cow, refused to pull his cars, so Swift leased his own and partnered with smaller lines to move them. Then, he built icing stations along the routes, and replenished them with ice he contracted directly with ice harvesters in Wisconsin and other cold midwestern states. By necessity, he built the whole cold chain from scratch.

This combination of centralized slaughter in Chicago and cold chain to the coast was his High Ground. He was forced into vertical integration because none of the pieces made sense on their own, but once he had it, he used it to drive down costs.

Like Rockefeller, Swift was appalled by waste, and because he controlled his own slaughterhouses, he could do something about it: he turned cow byproducts into soap, glue, fertilizer, sundries, even medical products, which allowed him to increase revenue and lower prices. He also maximized his refrigerated cars by stacking butter, eggs, and cheese beneath the swinging carcasses of dressed beef heading East.

By 1884, after only six years in operation as a slaughterer, Swift had become the second largest meatpacking firm in the US. By 1900, the meatpacking industry, unconstrained, had grown to become the second largest in the country to iron and steel.

Ford

It was a visit to a Chicago slaughterhouse that inspired Henry Ford’s assembly line. “Along about April 1, 1913, we first tried the experiment of an assembly line,” Ford writes in My Life and Work. “We tried it on assembling the flywheel magneto. I believe that this was the first moving line ever installed. The idea came in a general way from the overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef.”

Ford didn’t invent the automobile. By 1908, there were hundreds of American car companies selling expensive, hand-built machines to the wealthy. A typical car cost $2,000-$3,000, or roughly two and a half years’ wages for an average worker. Manufacturing costs were the constraints to the nascent automobile industry’s growth, so manufacturing costs were Ford’s Schwerpunkt.

Ford broke the constraint with the moving assembly line. Before it, a single worker assembled a complete flywheel magneto in about 20 minutes. Ford split the work across 29 operations, cutting the time to 13 minutes. Then he raised the line eight inches and cut it to seven minutes. Then he adjusted the speed of the line and cut it to five. The same progression played out across the whole car: total assembly time fell from over 12 hours per chassis to 93 minutes.

That manufacturing capability was the High Ground. The Model T launched in 1908 at $850, already half the price of the competition. As the assembly line improved, Ford kept cutting: $550 by 1913, $360 by 1916, below $300 by 1924. What had been 18 months’ wages for an average worker became four months’.

From that High Ground, Ford integrated ferociously. Rubber plantations in Brazil. Iron mines and timberland in Michigan. A glass plant, a railroad, a steel mill, even soybean farms for plastic components. All of it flowed into the Rouge River complex, where raw materials entered one end and half of the finished cars on the world’s roads rolled out the other.

The result was that Ford’s sales went from 12,000 in 1909 to half a million in 1916 to over two million in 1923. At its peak, more than half the cars in the world were Fords.

Across the Industrial Revolution’s most successful entrepreneurs, there was a clear pattern that looks almost nothing like how you’d think about scaling a SaaS business: identify the Schwerpunkt in an existing industry, break it, seize High Ground, integrate outward, dominate.

Pause for a second. Think about how people are telling you to analyze businesses today. Would those AI-generated moat lists, or the equivalent for their time, have given you any advantage whatsoever in identifying Rockefeller, Carnegie, Swift, or Ford, let alone becoming one of them? It is never that easy, and it always takes work.

I want you to feel those examples, because what’s old is new again. The biggest companies in the world today are executing against the same framework, in ways that are specific to their industry.

SpaceX Goes Vertical

The funny thing about today’s biggest software companies is just how much they spend on hardware. This year, the world’s four largest companies that started as software companies plan to spend an estimated $600-700 billion on data center buildouts, equivalent to roughly 2% of US GDP, a level of infrastructure buildout comparable to laying America’s railroads in the 1850s.

Amazon, an online bookseller, will spend $200 billion. Google, the search engine giant, will spend $175-185 billion. Meta, the social network for college students, will spend $115-135 billion. And Microsoft, which makes operating systems and office applications, will spend $100-150 billion.

Except, of course, that’s not what those businesses are. They are technology conglomerates that used the early internet to break the Schwerpunkt in their respective industries, gain their respective High Grounds, and integrate outward so far that they’re all running into each other at this new frontier. And despite their best efforts and hundreds of billions of dollars spent on terrestrial data centers, Elon Musk still thinks we’re going to need to put them in space.

SpaceX

Before SpaceX, the constraint in the space industry was cost to orbit. SpaceX broke the constraint with reusable rockets, drove costs down an order of magnitude, and quite literally gained the High Ground. From there, it integrated outward into Starlink communications satellites, which it can launch more cheaply than competitors because it owns the rockets and which fund the development of even bigger Starship rockets, which bring the cost per kg to launch things into orbit down even further. SpaceX used vertical integration the same way Rockefeller did: it is simultaneously its own largest customer and its own cheapest supplier. Casey Handmer’s The SpaceX Starship is a very big deal is an excellent read on the topic.

In 2023, Elon Musk founded xAI to build maximally truth-seeking AI. He then merged it with X (née Twitter). xAI got a late start, and it doesn’t have the best models yet, but what it is best in the world at is building data centers very fast. So the world took note when Elon said that we’d never be able to build enough data centers on earth to meet demand for AI, and that we will need to start building them in space.

So on February 2nd, 2026, SpaceX announced that “SpaceX has acquired xAI to form the most ambitious, vertically-integrated innovation engine on (and off) Earth, with AI, rockets, space-based internet, direct-to-mobile device communications and the world’s foremost real-time information and free speech platform.” According to Musk, SpaceX will get the data centers it needs in space via ~10,000 Starship launches per year, or roughly one per hour, every hour. Simultaneously, it will also build a self-growing Moon city, from which it plans to build a mass driver in order to make a terawatt per year of more worth of AI satellites, far more energy than Rockefeller could have conceived of, en route to eventually colonizing Mars and fulfilling SpaceX’s mission to “extend consciousness and life as we know it to the stars.”

It remains to be seen whether the High Ground will also give SpaceX a decisive advantage in the AI race, but it certainly demonstrates that the stakes have grown since the Industrial Revolution, even as the strategy has remained the same.

But no matter how that plays out, SpaceX (and Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, Apple, Tesla, NVIDIA, OpenAI, and Anthropic) aren’t going to eat everything, or else I wouldn’t be investing in startups.

The Hunt for the High Ground

Boulton and Watt did not capture the entire value of the Industrial Revolution they steam powered, although they did vertically integrate, Boulton into the Soho Manufactory, the steam engine-based Gigafactory of its day, and Watt, via his son, into steamships. Nor did Rockefeller eat everything in the internal combustion era of the Revolution despite owning the oil on which it all ran.

In addition to Rockefeller (oil), Boulton and Watt (steam engine), Carnegie (steel), Swift (meatpacking), and Ford (automobiles), the Industrial Revolution gushed multi-generational wealth for the Vanderbilts (railroads), Morgans (finance), Sears and Roebucks (retail), Havemayers (sugar), McCormicks (agricultural equipment, sadly unrelated), Westinghouses (power), Otises (elevators), Pullmans (luxury rail cars), Bells and Vails (telecommunications), Pulitzers and Hearsts (publishing), Eastmans (photography), Kelloggs (processed food), Pillsburys (milling), Singers (sewing machines), Nobles (Dynamite), DuPonts (chemicals), and Dukes (tobacco). This list is incomplete.

What’s notable is the diversity of industries that produced these fortunes. Machines made “labor” more abundant, and the companies that seized upon the technological innovation to break the Schwerpunkt in their specific industry, gain the High Ground, and expand were all wildly successful. Far from simply defending against mechanization, they seized the complementary assets to which value flowed as key inputs became abundant.

There are clear differences between AI, developed by huge labs and distributed at the speed of bits, and Industrial Era machine-filled factories, but I expect the Techno-Industrial Era to play out similarly. Each industry has unique constraints and resulting High Grounds, very few of which can be cracked and captured with digital intelligence alone.

The diversity that creates unique opportunities in each industry, however, makes underwriting those opportunities a different and more difficult beast than underwriting SaaS companies, which are more homogenous. There is no list, no spreadsheet, no agreed-upon metrics that will tell you which will become today’s Standard Oils. There is only the evaluation of constraints and hunt for High Grounds.

Instead of a list, then, let me give you my favorite example: Base Power Company.

Base Power Company

Base Power Company doesn’t just make batteries. It buys cells (the commoditized piece of the value chain), manufactures battery packs, installs them on homes (starting in Texas), writes software to coordinate them, trades in the power market, and partners with utilities to help balance the grid. Base is built on the type of logic companies (and their investors) will need to exercise if they want to compete in the modern era, and it goes something like this.

We want to fix power. What’s the bottleneck? The grid. Companies are competing to build power generation and the electric machines that consume that power, and the better they do, the more strain there will be on the grid. The grid is the chokepoint. So how do you fix the grid? Laying new transmission and distribution is slow and expensive, and the grid we have is already structurally underutilized because it’s built to serve peak demand, so to smooth it out, you need batteries. Where should you put the batteries? Centralized battery farms are helpful, but they need to wait in interconnect queues, which makes them slower to turn on, and those batteries still need to distribute power to end users when demand peaks, which means they don’t fully solve the bottleneck. So you need to put the batteries right next to demand. Fill them up when the grid has capacity, and use them to smooth demand when demand is high. And if you want to put batteries next to demand (homes, to start), where is the best place in the country to do that? Texas, which operates its own deregulated grid, ERCOT, is volatile (which means potential for higher trading profits and greater need on the part of customers and utilities), and is regulatorily friendly. So you start by putting batteries on the homes of early adopters within Texas. Those slots are scarce - it would take a lot for a customer to rip and replace their batteries, and no one is installing two companies’ batteries. Then, connect them with software, improve the grid and each customer’s experience with more batteries on the network, and use the richest source of demand available in the country to begin to scale. Bring manufacturing in-house, continue to improve the batteries, decrease their costs, get more efficient at installing them, connect more of them, sign more early adopter utilities, get more scale. At which point, it’s hard to imagine a viable way to beat Base at its own game. Then, expand. Integrate upstream into grid hardware and generation and downstream into electronic devices to sell into customers with whom you’ve built trust. Expand geographically, leveraging scale, experience, and software to offer a better product than a potential competitor attempting to grab a foothold by starting in the next-best market. Keep expanding. Dominate. Expand some more.

There are a couple things I want you to take away from that paragraph.

First, it is a very long paragraph. This is not simple or easy. I think investors bemoaning the Death of SaaS are in part sad that the era of underwriting software businesses on known, straightforward metrics is over. Underwriting the biggest companies of this generation will be a much more bespoke process. The time has come to move from simple analysis to strategy. It is not a coincidence that my first Deep Dive on Base was structured as a walk through the evolution of the strategy memos that Zach and Justin wrote before touching a single atom.

Second, as technology improves – from AI to the Electric Stack – the vast majority of the returns will accrue to the companies that figure out the right place to attack and execute violently against their conviction. A simple way to think about this is that better software is more valuable to Base than it is to a smaller competitor, to a battery farm operator, or to a power generation company, as is better hardware. Better robots for manufacturing and logistics would make Base faster and more profitable, and making the game more CapEx intensive would give it an advantage over would-be competitors.

The lesson from Base is not that hardware is a moat, or that you should put your product next to Texans’ homes.

It’s that you need to deeply understand the problem you’re trying to solve, the constraint that’s bottlenecking it, how you’re going to unblock it with technology (and why now?), and how you might expand to capture the market once you do. It applies differently in every industry.

For airlines, the constraint is the engine: today’s turbofan engines carry planes as fast and efficiently as they can. Everything bad in air travel is downstream of that. So Astro Mechanica is building a new engine that is faster and efficient at every speed. But certifying a commercial airline is a long and expensive process, so Astro plans to sell into Defense first, then build private supersonic planes (which are cheaper to certify and can be cost-competitive with first class tickets immediately), then build larger supersonic planes that are cost-competitive with commercial air travel, and use the advantage in speed and cost to build its own full-stack airline, from booking to flight.

For internet, the constraint is the architecture: incumbent telcos froze their architectures around early-2000s assumptions about what was expensive, locked themselves into passive optical networks and vendor dependence, and now spend billions every few years on upgrades that still deliver shared, degraded bandwidth with no redundancy. They do zero R&D. So Somos Internet is rebuilding the full stack from scratch: an Active Ethernet architecture borrowed from data centers, physically simple with complexity pushed to software, that delivers dedicated bandwidth to every home at a fraction of the CapEx. As it grows, Somos eats more of its supply chain: “It’s been this never-ending game of doing something janky, getting credibility, doing crazier stuff, getting more resources, getting smarter people so that we can fix the things that were messed up in the janky past iteration,” Forrest explained. “Then gaining credibility to get more resources to get cooler people to do crazier stuff. It’s like this self-sustaining fission process.” Somos is expanding geographically, into new markets, vertically, by making its own hardware and laying its own fiber, and horizontally, building hydro-powered data centers. From the position of delivering one of the few home utilities everyone pays for, better, faster, and cheaper than incumbents, it plans to expand what it offers the customers with whom it’s built trust and loyalty. Maybe one day, it will offer batteries and power. Maybe one day, it will use its growing cash position to enter the United States.

There are a lot of similarities between Base and Somos: both own a core home utility and deliver it better than incumbents, which earns them the right to expand. But there are differences, too. Base is starting in the very best market for its technology, because that’s where the need is greatest and the regulatory environment is friendliest. If Somos started somewhere like New York City, it would be caught up in red tape and slow, expensive telco lawsuits for years; so it’s starting in a high-need, regulatorily friendly environment and building up cash for bigger battles. And Astro’s approach is almost entirely different from both Base’s and Somos’, apart from using better technology, now feasible thanks to Curve Convergence, to break a constraint and capture the High Ground. For one thing, people go to planes, so Astro can’t capture their real estate in the same way that Base or Somos can.

There I go with the long paragraphs again. Fine. There is endless nuance to this.

I am talking my own book here, not because I think my portfolio companies are the only businesses that will succeed in the Age of Intelligence, but because I understand their strategies much more thoroughly. Very smart people will disagree with me on each industry’s Schwerpunkts and potential High Grounds. And even once you’ve done all this work on paper, so much comes down to execution. Will the team that identified the right strategy be the same one that can build against it to capture the opportunity? Only time will tell. That’s what makes this so much fun - it’s not obvious!

What is obvious, and I hope clear at this point, is that there is no one answer, no handy guide that will tell you how to win in the Age of Intelligence. Which means that there is also not one business model.

A Note on Business Models

While the “Death of SaaS” is overblown, what I hope this freak out does is to end the default investor assumption that every business should try to be a SaaS business.

A week before the sell-off, I met with three separate founders who told me that investors didn’t like their businesses because they weren’t SaaS. In two cases, the founders were building services businesses – traditionally a huge venture red flag. In all three, they believed the technology they were building was so good that they could use it to compete directly with incumbents instead of selling them software that made them marginally more productive.

During the sell-off, Flexport’s Ryan Petersen tweeted that everyone “smart” had told him to just build SaaS. The idea being that it would be easier to sell to freight forwarders instead of actually becoming a freight forwarder and competing.

Other founders quote tweeted him saying they’d been given, and ignored, the same advice, including Cover’s Alexis Rivas, whose company builds houses. I’m not even sure what selling software would look like here.

This is not because investors are dumb. Selling software has real advantages, and those advantages are legible more quickly. Two of those three founders I spoke to said that they had competitors who were selling software and generating a lot of revenue quickly, which is why investors thought they should be doing the same.

In the past, that was a logical discussion to have: should you try to sell software to generate lots of high gross margin revenue in the near-term in a way that’s legible to downstream capital so that you can continue to raise and hopefully give yourself time to develop moats, or should you try to compete directly, with better technology and a chance at better economics within whatever your industry’s business model is, even if those economics are worse than SaaS economics, in pursuit of the larger and ultimately more impactful shot at winning and reshaping your industry?

In most cases, that is no longer a debate. AI squeezes it from both sides. From one side, SaaS is a more competitive, less defensible business; there will be enough competitive noise that it’s harder to establish traditional moats like network effects and switching costs, and customers big and sophisticated enough to actually pay a lot and make use of your tool may opt to build something custom themselves. From the other, the technology is so powerful in the right hands that it should provide a stronger force with which to attack the Schwerpunkt than deterministic software could have. In other words, it is more likely than ever that a technology-native new entrant can defeat incumbents, assuming their technology actually addresses the industry’s key constraint.

What this means is that investors need to get comfortable with a wider range of business models to accommodate whichever is the right one for the industry in which a company operates. This does not mean that they should treat all business models equally now. Instead, they need to stop blind pattern matching altogether.

Services businesses might still be terrible for most businesses, but exactly the right model for some. Stripe clearly shouldn’t be a services business; maybe an AI-native law firm should. Selling hardware to incumbents might be a bad business model, not simply because hardware is hard, but because buyers have all the power in a particular industry, or because existing suppliers have locked buyers into whole sticky ecosystems. What might be better is to use that better hardware as the High Ground from which to integrate and compete.

A question I would like to see more investors asking instead of “Why not sell SaaS” is:

If your technology is so good, why aren’t you using it to compete?

Some companies find out that selling software to incumbents is the wrong model only through trial-and-error. My favorite example here is Earth AI.

Earth AI developed AI models to identify drilling targets for mining explorers back before AI was a thing, and sold it to explorers for a very good price at high margins. The challenge was: they never heard back from their customers. Many went bust - exploration is a notoriously binary business - which meant they stopped paying; retention was hard. Many others just had no incentive to report back, which meant that Earth AI wasn’t learning which of its targets were good and bad, which meant that it couldn’t improve its models. So it bought its own rig and went to customer sites to go find out for itself, and then it realized that it could build better rigs, and combine them with better models, and just compete directly. As I wrote in my Deep Dive:

The same thing that makes exploration customers bad customers – slowness, unwillingness to adopt technology – makes them very attractive competitors, if your tech actually works as well as you say it does. If you’re willing to vertically integrate – to do exploration, and drilling, and maybe even extraction – you might be able to build the most efficient explorer out there.

To be clear, Earth AI’s current business model is much more confusing than selling software. It has to invest in rigs up front, stake deposits, put teams on site to prove them out, and keep proving feasibility until a downstream miner wants to buy a stake in the deposit or buy the whole deposit outright and pay Earth AI a royalty, at which point, it becomes one of the most beautiful business models there is. Mining royalty & streaming companies have some of the highest market caps per employee in the world. Franco Nevada is worth $48 billion with just 41 employees, good for $1.2 billion per employee! Earth AI has the potential to build up a similar portfolio at a much lower cost basis because it is willing to dig.

The point is, maybe you drill mineral deposits in Australia to build a portfolio of mines, maybe you buy cells, manufacture battery packs, install them on homes, and make money by becoming a Retail Electric Provider, trading power, and selling ancillary services, maybe you hire expensive humans, make them much more efficient, and sell their time, maybe you even sell software!

Whatever you need to do to break the constraint, gain the High Ground, and win your industry is what dictates the business model you should pursue.

You Can Even Sell Software, As Long as You Win

Sometimes, the Gods smile on an essay. As I was writing this, Stripe co-founder John Collison released the latest episode of his podcast, Cheeky Pint. His guest: Eric Glyman, the CEO of Ramp.

Responding to John’s first question, Eric described Ramp’s evolution in terms that should now sound familiar. A few years ago, Ramp’s gross profit was over 90% card interchange. Today, the non-card businesses, including bill payments, treasury, procurement, travel, and software, will comprise the majority of Ramp’s contribution profit.

Ramp used a card, software, and counter-positioning to attack what it viewed as the Schwerpunkt in corporate spend (the fact that everyone was selling money, and no one was selling time) and win the transaction layer, the High Ground from which it is now expanding to eat every point solution a finance team touches.

Throughout the conversation, he lays out from his inside view exactly how and why this is happening. Everything flows from earning the High Ground. Ramp has data that no one else has and that no new entrant can accumulate more quickly. As it adds more intelligence, it gets more data. It’s built the things that are too expensive to replicate with more tokens – “I think the fitness function for companies becomes can you actually do things in such a way where even if you could spend tokens on it, it would take more tokens to create the thing or do that work than the system that you’ve built to drive that outcome.” – and is happily spending tokens to build everything else. And as it adds more features, it grows. The company now “powers more than 2% of all corporate and small business card transactions in the United States.” The larger its share, the more it learns, the more it makes, and the more tokens it can throw at eating adjacent opportunities, which keep feeding the machine.

This is why Ramp is valued at $32 billion while Brex sold for $5.15 billion. It is why Stripe is worth multiples of Adyen. It is why Base, only two years old, was valued at $4 billion.

The ownership of the scarce position in an industry is itself a scarce asset. The market, whether it uses this language or not, is including in its valuation the belief that from that position, you can eat an industry.

In doing so, they are leaning on history and economic data. Once Rockefeller smoothed refining’s volatility and began to get scale advantages in the 1860s, it was fait accompli. Once SpaceX drove down the cost of putting mass in orbit, and used that advantage to build a telecommunications cash cow that it could use to reinvest in cheaper launch, it became the leading candidate to win whatever economically valuable use cases required putting a lot of mass in orbit. Before Elon realized space data centers were going to be a thing, he’d won the right to win space data centers.

If you are confident in your analysis of the constraint and High Ground in an industry, and of which company is best positioned to break the former to win the latter, you can pay a premium under the assumption that more of that industry’s economic value will flow to the leader. That trend - increasing concentration of economic value - is a long and stable one, accelerated by new technologies.

Today, our new technologies are more powerful and general purpose than ever before, which means that the ability of category leaders who are able to wield those technologies is greater than ever before. They are levered to the pace of technological progress.

If AI gets smarter, Stripe and Ramp can eat more adjacencies, faster. If battery cells get more efficient, Base can offer a better service to its retail and utility customers. As power electronics continue to improve, Astro Mechanica can build faster, more efficient engines.

Whether SaaS is dead is one of the least interesting questions in the world. SaaS as a wellspring of valuable businesses, almost regardless of those businesses’ actual power, was a historical anomaly.

That doesn’t mean software is dead. We will see software businesses become some of the largest businesses in history, just as we will see hardware and even services businesses that dwarf Standard Oil’s size. Economic inputs are becoming more abundant, which means that more value will flow to the scarce complementary assets. This will continue as long as the abundance does.

The question that matters now is how you plan to win your industry. Everything else follows.

Power in the Age of Intelligence flows to the winners. Winners take more.

That’s all for today. We’ll be back in your inbox Friday with a Weekly Dose.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Another banger—well done

Great read! Have you seen any opps to invest in Base?