a16z: The Power Brokers

a16k word essay on a16z on the day of a15b fundraise

Welcome to the 310 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since Tuesday! Join 256,606 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

This article reflects the views and opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views or beliefs of a16z. Investment returns are included throughout this article. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See related fund returns and disclosures at the end of this piece.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Friday! IT’S TIME TO WRITE about a16z.

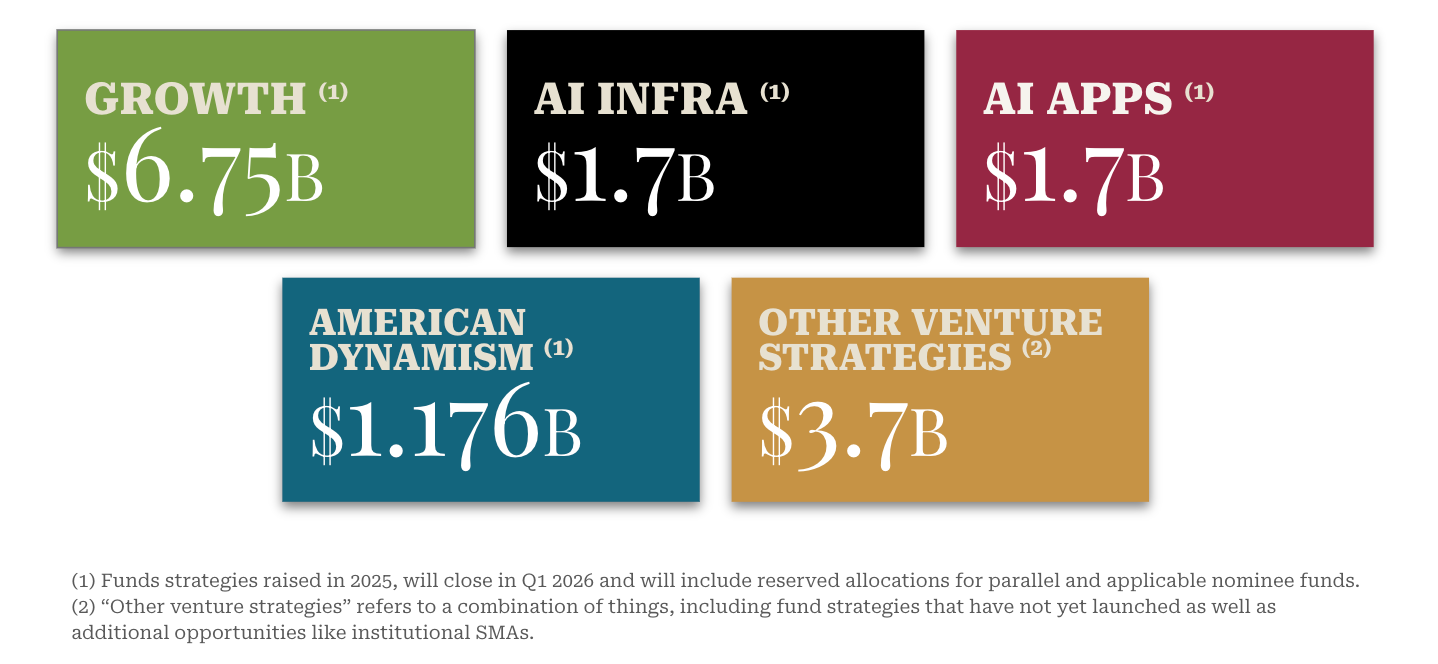

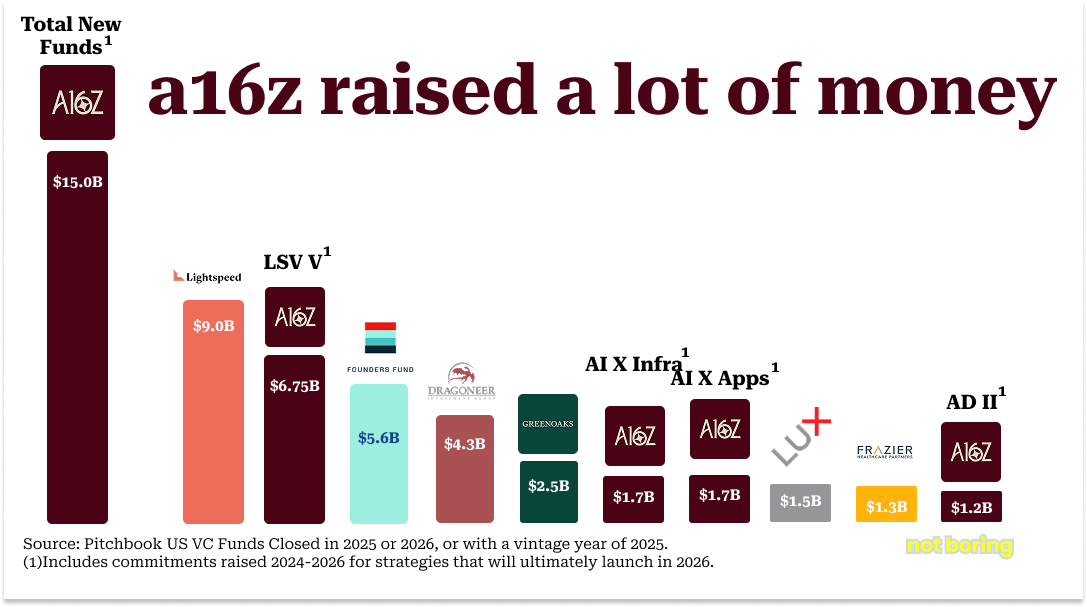

Today, a16z is announcing $15 billion in fresh funds.

To commemorate the occasion, I’m writing a Deep Dive on the Firm. I spoke with Firm’s GPs, LPs, ~$200 billion worth of portfolio founders, reviewed documents and presentations, and analyzed returns data for a16z’s funds since inception (see appendix with disclosure information at the end).

There is a lot of writing on the internet about what’s wrong with a16z’s approach. You probably know the arguments. They’ve followed the firm since inception.

I think it is much more interesting to understand just what it is that all of these smart people who have been right in the past think it is that they’re doing now.

And look, I am about as far from an unbiased observer as anyone without an @a16z.com email address could be.

For more than two years, I was an advisor to a16z crypto (but am currently not compensated by the firm). Marc Andreessen and Chris Dixon are LPs in not boring capital. From time to time, I am on the same cap table as a16z. I am friends with a lot of people in the Firm and with most of the New Media team. I partner with, like, and respect these people.

But look, we’re not counting on me to analyze whether a16z’s pitch at this moment in time is worth investing in. Sophisticated institutional LPs have decided, to the tune of $15 billion, to do so. It will take a decade to know whether they made the right decision, and nothing either I or any hypothetical critic could say will change that outcome, just as it hasn’t in the past.

What I can hopefully bring is a way to think about what a16z actually is from my unique experience. I think a16z is the best-marketed Firm in venture. It can, and does, tell a story about itself. Based on my experience, I can tell you that its story is consistent with its actions. The things that a16z says about itself to the public are the same things it trains its team on internally. The pitch it makes is the same one it’s made since its first Offering Memorandum. And you will be able to judge the returns for yourself.

There are a lot of great venture capital funds and investors, some of the best of whom have been profiled recently. Their approaches and successes are increasingly well-appreciated and well-understood.

But a16z is doing something different, bigger, less… understated. It doesn’t feel like venture capital is supposed to, in part, I think, because I don’t think a16z cares if it’s doing “venture capital.” It just wants to BUILD the future and eat the world.

To read the full Deep Dive in your browser, click here.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Vanta

Compliance is painful, but if ya want to grow, ya gotta do it. Luckily, Vanta’s got you covered.

Get Vanta’s Compliance for Startups Bundle here, and get back to growing.

a16z: The Power Brokers

“I’m living in the future so the present is my past,

My presence is a present kiss my ass.” – Kanye West, Monster

Andreessen Horowitz hears your feedback.

That it’s too loud. That it should shut up and dribble, politically speaking. That you don’t agree with a recent investment or two. That it is unbecoming to Quote Xeet the Pope. That there is no way it will ever generate a reasonable return for LPs on such enormous funds.

a16z does hear you. It has been hearing you, at this point, for nearly two decades.

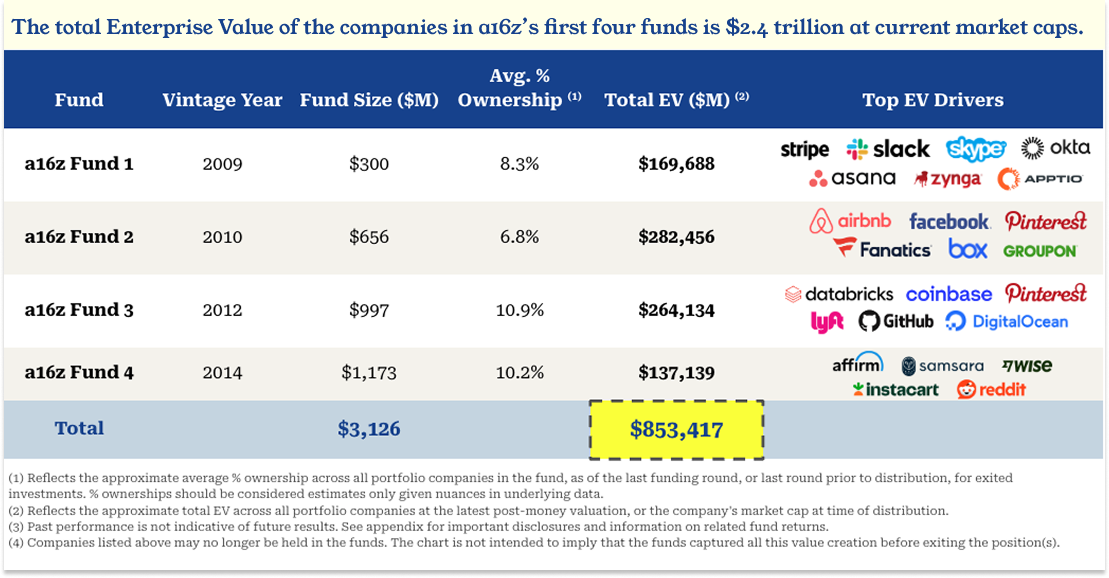

Like in 2015, when New Yorker writer Tad Friend sat down to breakfast with Marc Andreessen while writing Tomorrow’s Advance Man. Friend had just heard from a rival VC who wanted to get a word in - that a16z’s funds were so large, and ownership percentages so small1, that to get 5-10x aggregate returns across its first four funds, they’d need their aggregate portfolio to be worth $240-480 billion.

“When I started to check the math with Andreessen,” Friend writes, “He made a jerking-off motion and said ‘Blah-blah-blah. We have all the models—we’re elephant hunting, going after big game!’”

I want you to keep that image in your mind. To preempt Marc’s reaction to the reaction you’re about to have to the next paragraph.

Today, a16z is announcing that it has raised $15 billion across all of its strategies, bringing its total regulatory assets under management (RAUM) to over $90 billion.

In a year in which venture fundraising was dominated by a small number of large firms, a16z raised more than the next two funds - Lightspeed ($9B) and Founders Fund ($5.6B2) - raised in 2025, combined.

In the worst VC fundraising market in five years, a16z accounted for over 18% of all US VC funds raised in 20253. In a year in which it took the average VC fund 16 months to close their fund, a16z took just over three months from start to finish.

Split up, four of a16z’s individual funds would be in the 2025 top 10 among entire firms’ raises: Late Stage Venture (LSV) V would be #2, Fund X AI Infra and Fund X AI Apps would be tied for 6th, and American Dynamism (AD) II would be tenth.

One could argue that this is way too much money for a venture fund to deploy with any reasonable expectation of generating outsized returns. To which, I imagine, a16z collectively makes a jerking-off motion and says, “Blah blah blah.” It is elephant hunting, going after big game!

Today, across all their funds, a16z is an investor in 10 of the top 15 private companies by valuation: OpenAI, SpaceX, xAI, Databricks, Stripe, Revolut, Waymo, Wiz, SSI, and Anduril.4

It has invested in 56 unicorns over the prior decade through its funds, more than any other firm.5

Its AI portfolio includes 44% of all AI unicorn enterprise value, also more than any firm.6

And from 2009-2025, a16z led 31 early rounds of eventual $5b companies, 50% more deals than the two next closest competitors.

It has all the models. It has the track record, now, too.

Below is the aggregate portfolio value of those first four funds, the ones that would have had to be worth $240-480 billion to clear that rival VC’s hurdle. Combined, a16z Funds 1-4 had a total enterprise value of $853 billion at distribution or latest post-money valuation7.

And that was just at the time of distribution. Facebook alone has added more than $1.5 trillion in market cap since!

Some form of this pattern keeps playing out: a16z makes a crazy bet on the future. Those in the know say it’s stupid. Wait some years. Turns out it’s not stupid!

a16z raised its $300 million Fund I in 2009 on the heels of the Global Financial Crisis, touting an operating platform to support founders. “We visited a lot of our VC friends and many of them said it was a really dumbass idea and we should definitely not pursue it and it’s been tried before and it didn’t work,“ Ben recalls. Today, nearly every significant VC has some flavor of platform team.

When it invested $65 million of that fund alongside Silver Lake and other investors to acquire Skype from eBay for $2.7 billion in 2009, “everyone said it was an undoable deal due to IP risk” (eBay was in litigation with Skype’s founders over the technology at the time of the deal). Ben recounted the skepticism in a blog post less than two years later when Microsoft acquired Skype for $8.5 billion.

Marc and Ben raised a $650 million Fund II in September 2010, and proceeded to make large late-stage investments in companies like Facebook ($50 million at $34 billion), Groupon ($40 million at $5 billion), and Twitter ($48 million at $4 billion), betting the IPO window would open. Rivals bristled to The Wall Street Journal in a classic, A Venture-Capital Newbie Shakes Up Silicon Valley, that private share deals were just not what venture capitalists did (the now-common practice was so new that the word “secondary” makes no appearance). Matt Cohler, a Benchmark partner, dropped this banger: “There’s also money to be made in pork bellies and oil futures, but that’s not what we do.” In November 2011, Groupon IPO’d, opening at $17.8 billion. In May 2012, Facebook IPO’d at $104 billion. And in November 2013, Twitter IPO’d, closing its first day at $31 billion.

By the time Marc and Ben raised a $1 billion Fund III and a $540 million parallel opportunities fund in January 2012, the criticism shifted to a familiar one: scale. a16z’s funds represented 7.5% of all US VC dollars raised in 2012, while VC kind of sucked. The 2014 Harvard Business School Case Study on a16z notes a 2012 Kauffman Foundation report which found that, “Venture capital has delivered poor returns for more than a decade.” In 2012, VC investments returned an average of 8.9% to the S&P 500’s 20.6% per Cambridge Associates. Legendary venture capitalist Bill Draper said, “The growing consensus about venture capital in Silicon Valley is that too many funds are chasing too few truly great companies.” Which certainly rhymes with today.

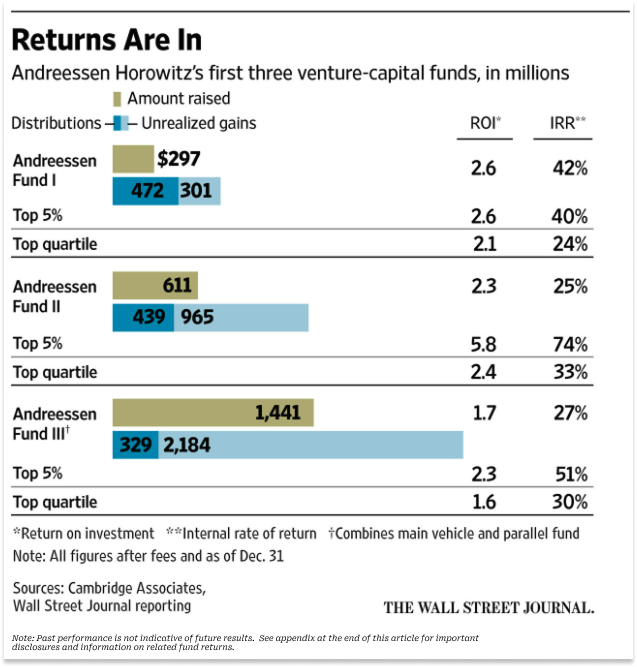

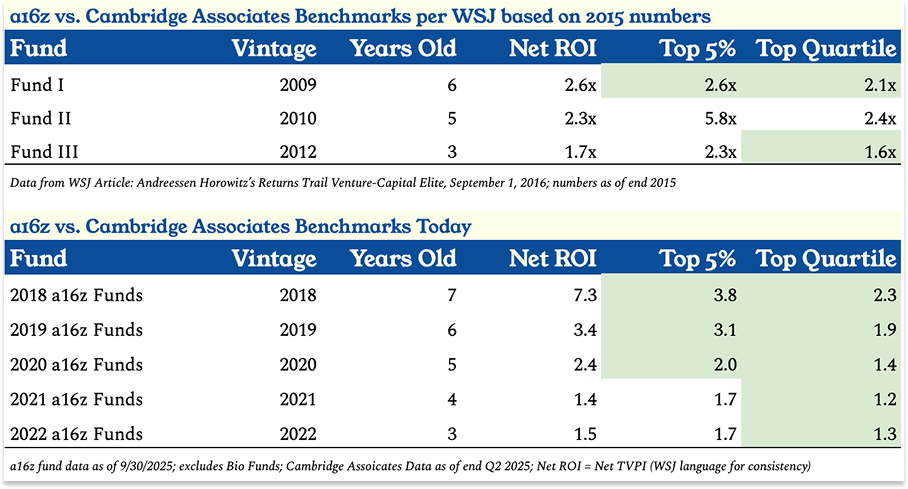

In 2016, The Wall Street Journal published an article that Acquired’s David Rosenthal called “so clearly a hit piece planted by rival venture firms” titled Andreessen Horowitz’s Returns Trail Venture-Capital Elite, when its funds were seven, six, and four years old, respectively. It showed that while AH Fund I was a top 5% VC fund, AH II was merely top quartile, and AH III was actually slightly outside of the top quartile.

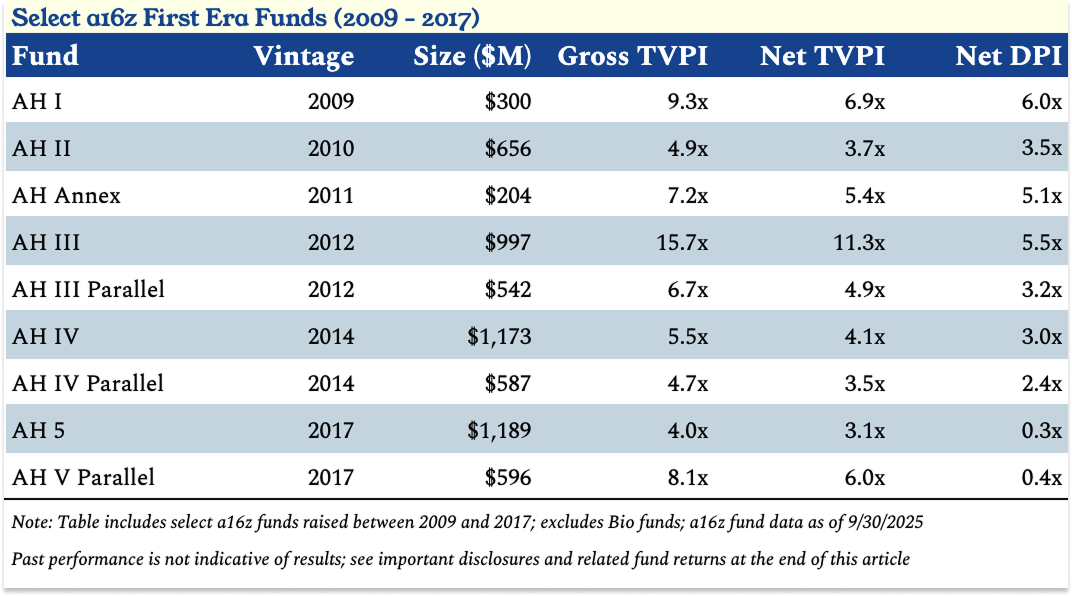

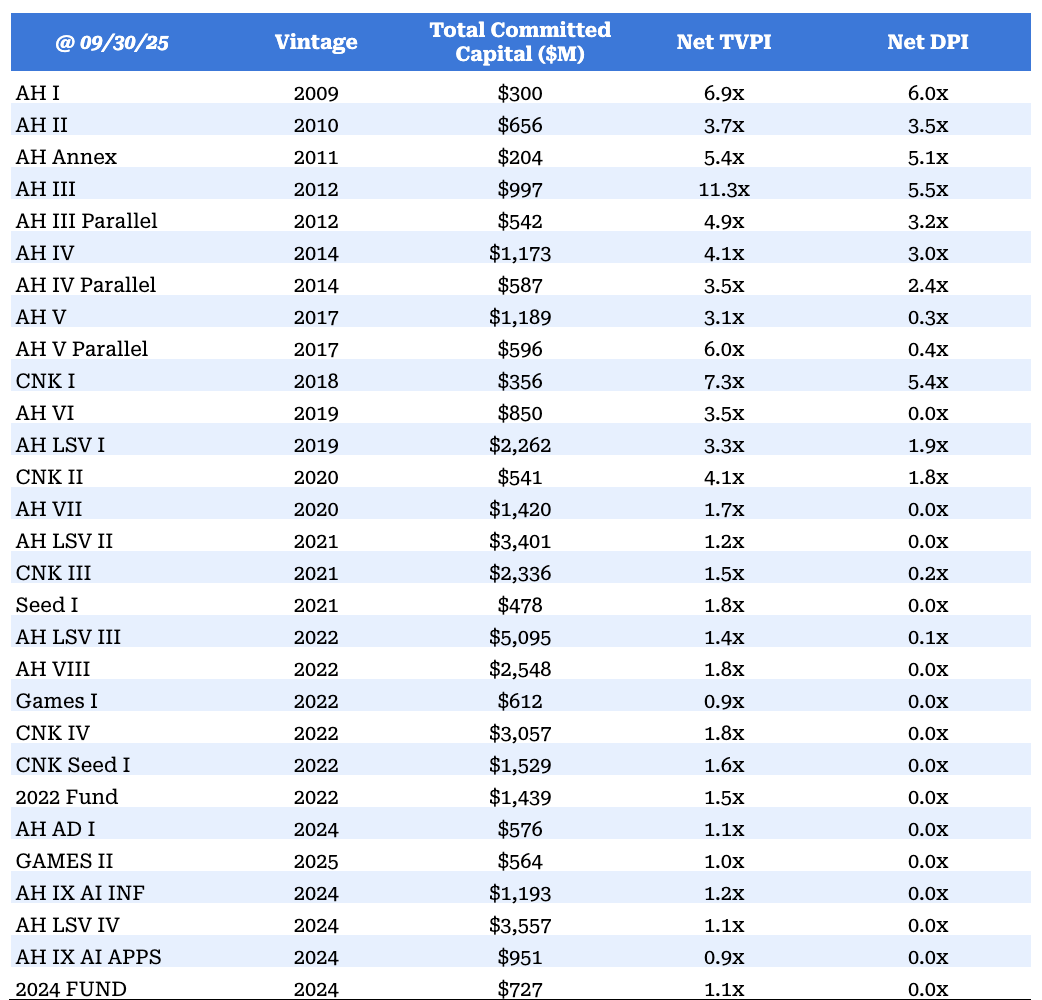

Which is funny, in hindsight, because that fund, AH III, is a monster fund: sitting at an 11.3x Net TVPI (total value to paid-in capital after fees) as of September 30 2025, and when you include the parallel fund, it’s at a 9.1x Net TVPI.

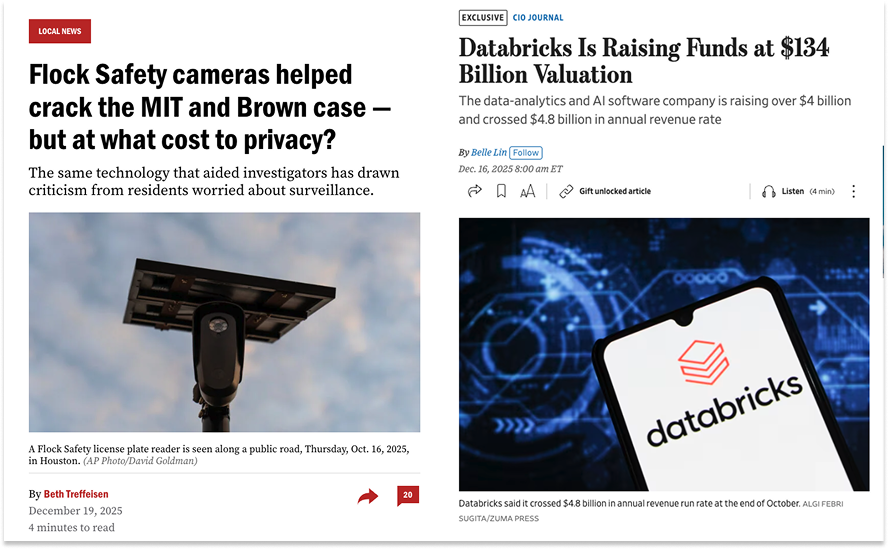

AH III includes Coinbase, which resulted in distributions of $7 billion gross to a16z LPs across the funds it’s in, Databricks, Pinterest, GitHub, and Lyft (although not Uber, proof positive that one sin of omission trumps every sin of commission), and I believe is one of the best performing large venture funds of all time. Since Q3 2025, Databricks (currently a16z’s largest position) raised at $134 billion, which means Fund III’s performance is even stronger now (assuming other positions have not decreased). a16z has already distributed $7 billion net to LPs from AH III and AH III Parallel with nearly as much in Unrealized Value still on the table.

Much of that unrealized value sits in one company, Databricks: a big data company that was very small, still a few months away from hitting the half-billion-dollar valuation mark, when the WSJ was writing off a16z in 2016. Databricks represents 23% of a16z’s Net Asset Value (NAV) across all funds.

Spend any time around a16z and you will hear the name Databricks a lot. In addition to being its largest position (and what must be a top three largest dollar position in all of venture capital), its story is the cleanest example of how a16z operates at its best.

Databricks & the a16z Formula

There are some things about the Firm we haven’t discussed yet that are useful to understand before we start talking about Databricks.

First, a16z is founded and run by engineers. Not just founders, engineer-founders. This influences how they designed the Firm (to feast on scale and network effects), and also how they pick markets and the companies within them.

Second, there is perhaps no bigger investing sin at a16z than investing in second best. If you miss a winner early, you can always invest in a later round. If you invest in second best, you lock yourself out from investing in the winner. This is true even if the eventual winner isn’t yet born.

Third, once a16z believes it has identified the category winner, the classic a16z move is to give it more money than it thought it needed. Everyone makes fun of them for that move.

These three things have been true since the Firm’s earliest days.

Back in the early 2010s, just a couple of years into the founding of Andreessen Horowitz, Big Data was the Big Thing (you remember this) and the era’s dominant Big Data framework was Hadoop. Hadoop used a programming model called MapReduce (originally developed by Google) to distribute computing across clusters of cheap commodity servers instead of on expensive specialized hardware. It ~*Democratized Big Data*~ and a wave of companies sprung up to facilitate and capitalize on that democratization. Cloudera, founded in 2008, raised $900 million in 2014, leading a year in which investment in Hadoop companies had quintupled to $1.28 billion. Hortonworks, spun out of Yahoo!, IPO’d that year.

Big data, big dollars. And a16z made none of them.

Ben Horowitz, the “z” in a16z, didn’t like Hadoop. A computer science major before he was CEO of LoudCloud/OpsWare, Ben didn’t think Hadoop was going to be the winning architecture. It was notoriously difficult to program and manage, and Ben thought it was poorly suited for the future: every step in a MapReduce computation wrote intermediate results to disk, which made it painfully slow for iterative workloads like machine learning.

So Ben sat out the Hadoopla. And Marc, Jen Kha told me:

Was just giving him so much shit, because at that point, Hadoop was taking over the headlines, and he was like, ‘We fucking missed it. We totally bungled this. We dropped the ball.’

And Ben was like, ‘I don’t think this is the next architectural shift.’

Then finally, when Databricks came around, Ben said, ‘This might be it.’ And he of course just bet the farm on it.

Databricks came around just in time and just down the road in UC Berkeley.

Ali Ghodsi and his family fled Iran in 1984 during the Iranian Revolution and moved to Sweden. His parents bought him a Commodore 64, which he used to teach himself how to code, well enough, in fact, to get invited to UC Berkeley as a visiting scholar.

At Berkeley, Ali joined the AMPLab, where he was one of eight researchers, including thesis advisors, Scott Shenker and Ion Stoica, working to implement the idea in Ph.D. student Matei Zaharia’s thesis paper and build Spark, an open source software engine for big data processing.

The idea was to “replicate what the big tech companies did with neural networks without the complex interface.” Spark set the world record for data sorting speed and the thesis won the award for best computer science dissertation of the year. True to academic form, they released the code for free, and barely anyone used it.

So starting in 2012, the eight met for a series of dinners, over which they decided to team up to start a company on top of Spark. They called it Databricks. Seven of the eight joined as cofounders, and Shenker signed on as an advisor.

Databricks, the team thought, would need a little money. Not a lot, but some. As Ben recounted to Lenny Rachitsky:

When I met with them they were like, ‘We need to raise $200,000.’ And I knew at the time that what they had was this thing called Spark and the competitor was something called Hadoop, and Hadoop had very well-funded companies already running towards it, and Spark was open source, so the clock was ticking.

He also realized that as academics, the team would be pre-disposed to doing something small. “Professors in general… it’s a pretty big win if you start a company and you make $50 million. Like you’re a hero on campus,” he told Lenny.

Ben had bad news for the team: “I’m not going to write you a check for $200,000.”

He also had really good news for the team: “I’ll write you a check for $10 million.”

His reasoning was, if you’re going to build a company, “You need to build a company. You need to really go for it if you’re going to do this. Otherwise, you guys should stay in school.”

They decided to drop out. Ben upped the check size and a16z led Databricks’ Series A at a $44 million post-money valuation. It owned 24.9% of the company.

This initial encounter - Databricks asking for $200k, a16z going much, much bigger - set a pattern. When a16z invests in you, they believe in you.

When I asked him about a16z’s impact, Ali was unequivocal: “I don’t think Databricks would be around today if it wasn’t for a16z. And Ben specifically. I don’t think we would be around. They truly believed in us.”

In the company’s third year, it was only doing $1.5 million in revenue. “It was far from clear that we would make it,” Ali recalls. “The only person that truly believed it was going to be worth a lot was Ben Horowitz. Much more so than us. Mind you, like, much more than me. To his credit.”

Belief is a cool thing to have. It’s even more valuable when you have the power to make it self-fulfilling.

Like in 2016, when Ali was trying to get a deal done with Microsoft. From his perspective, with overwhelming demand to have Databricks on Azure, it was a no-brainer. He asked some of his VCs for introductions to Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, which they did, but then those introductions got “buried in executive assistant loops.”

Then Ben introduced Ali to Satya properly. “I had an email from Satya saying, ‘We’re absolutely interested in having a very deep partnership,’” Ali recalls, “adding his lieutenants, and their lieutenants. Within a couple hours, I had 20 emails in my inbox, from Microsoft employees who I had tried to talk to before, and they were all like, ‘Hey, when can we meet?’ And it was like, ‘Okay, this is different. This is going to happen.’”

Or in 2017, when Ali was trying to recruit a senior sales executive to keep the foot on the gas. The executive wanted change of control provisions in his contract – essentially, accelerated vesting if the company gets acquired.

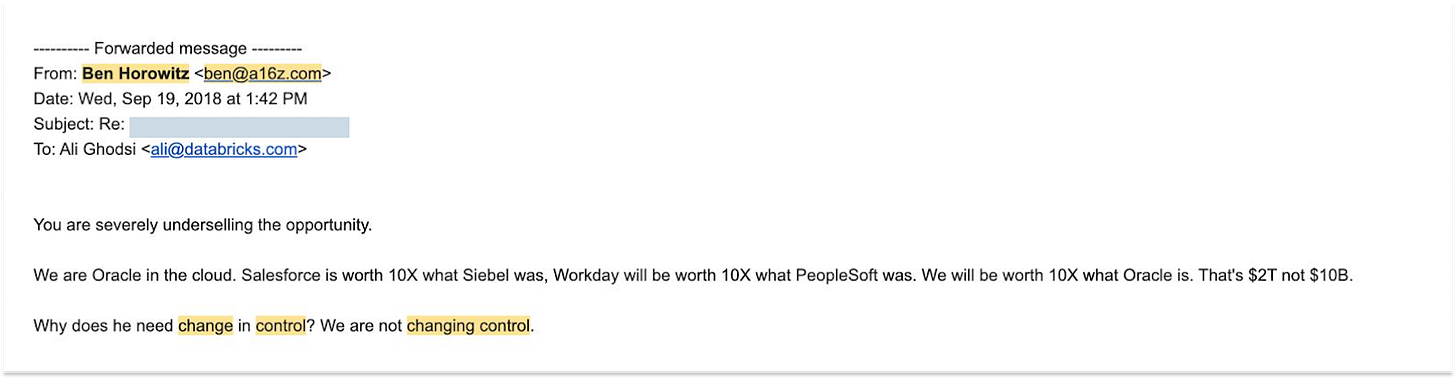

It was a sticking point, so Ali asked Ben to help convince the guy that the value of Databricks was “at least $10B.” Ben talked to him, and then sent Ali this email:

“You are severely underselling the opportunity.

We are Oracle in the cloud. Salesforce is worth 10X what Siebel was. Workday will be worth 10X what PeopleSoft was. We will be worth 10X what Oracle is. That’s $2T not $10B.

Why does he need change in control? We are not changing control.”

That’s one of the hardest corporate emails of all time, especially considering that Databricks was worth $1 billion at a $100 million revenue run rate then and is worth $134 billion at a more than $4.8 billion revenue run rate now.

“They envision the full potential of the thing,” Ali tells me. “When you’re knee deep in it, like we are operating every day, and you’re seeing all the challenges—the deals are not closing, the competitors are beating you, you’re running out of money, no one knows who you are, people are quitting on you—it’s hard to think about the world that way. But then they come to the board meetings and they tell you, ‘You’re going to take over the world.’”

They were right, and they’re getting paid for their belief. All told, a16z has invested in all twelve Databrick’s funding rounds. It has led four of them. The company is one of the reasons AH 3, from which the Firm did its initial investment, is doing so well, and it is a driver of returns in the larger Late Stage Ventures Funds 1, 2, and 4.

“First and foremost, they just really care about the mission of the company. I don’t think Ben and Marc think of it as an investment return first. That comes second,” Ali observed. “They’re tech believers who want to change the world with technology.”

If you don’t understand what Ali said about Marc and Ben, you will not understand a16z.

What is a16z?

a16z is not a traditional venture capital fund. On its face, this is obvious! It just completed the largest VC fundraise across all of its strategies since SoftBank’s $98 billion Vision Fund in 2017 and Vision Fund II in 20198. Nothing traditional about that. But even the SoftBank Vision Fund was a Fund. a16z is not that.

Of course, a16z has raised money and needs to generate returns. It needs to be great at this, and to date, it’s been exceptional. Not Boring has returns data on a16z’s funds to date that we will share below.

But first - what is a16z?

a16z is a cult of technology. Everything it does is to bring about better technology to make the future better. It believes that “Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential.” Everything flows from that. It believes in the future and bets the firm that way.

a16z is a Firm. It is a business, a company. It is built with the goal to scale, and to improve with scale. There are many characteristics of a Firm that I believe do not apply to a traditional Fund, and we will cover them. I think this distinction solves one of the oddest things about venture capital’s self-image: that venture capital is an industry that sells the world’s most scalable product (money) to its most scalable companies (technology startups) but must not, itself, scale.

This distinction - Firm > Fund - comes from a16z GP David Haber, the most East Coast Finance of the bunch and a self-described student of investment firms as businesses. “The objective function of a fund is to generate the most carry with the fewest people, in the shortest amount of time possible,” he explains. “A Firm is about delivering exceptional returns, and building sources of compounding competitive advantage. How do we get stronger with scale, not weaker?”

a16z is run by engineers and entrepreneurs. Money managers stereotypically try to grab larger pieces of a fixed pie. Engineers and entrepreneurs try to grow the pie by building and scaling better systems.

a16z is a temporal sovereign. It is the institution for the future. The Firm, in its more ambitious moments, views itself as a peer to the world’s leading financial institutions and governments. It has said that it aims to be the (original) JP Morgan for the Information Age, but I think that undershoots the true ambition. If governments work on behalf of chunks of space, a16z works on behalf of that big chunk of time that is the future. Venture capital is simply the way that it’s found it can have the biggest impact on the future, and the business model most aligned with profiting when it does.

a16z makes and sells power. It builds its own power through scale, culture, network, organizational infrastructure, and success, and then gives its power to the technology startups in its portfolio through sales, marketing, hiring, and government relations, primarily, although to hear its founders tell it, a16z will do whatever is in its power to do, which seems to be a lot.

If you were designing such an institution, one that believes that technology is “eating markets far larger than the technology industry has historically been able to pursue,” that Everything is Technology, what you would build is a company that sells the power to win to the hundreds and thousands of companies that might one day come to be the economy. I think you would build an institution that looks a lot like a16z.

Because the companies that might one day become the economy start small and fragile. They start diffuse, each with their own goals and competitors; often, they compete with each other. And they face entities that dominate the present, with no desire to cede ground to new entrants. A small company, no matter how promising, may not be able to hire the very best recruiters who can hire the very best engineers and executives. It might not be able to advocate for policies to give itself a fair shot. It may not have the audience to get its message out to the world in a way that people will listen. It may not have the legitimacy to sell its products to governments and large enterprises who are flooded with pitches promising the next big thing.

It doesn’t make sense for any one small company to invest the billions of dollars it would need to create those capabilities and amortize them over only itself. But if you can amortize those capabilities across all of those companies, across trillions of dollars of future market value, then all of a sudden, the small companies can have the resources of the big companies. They can win or lose on the merits of their product. They can bring about the future the way it should be.

What if you could combine the agility and innovation of a startup with the power and heft of a temporal sovereign?

That’s what a16z is trying to do, and has been trying to do since it was a startup itself.

Why Marc & Ben Started a16z

In June 2007, Marc wrote a blog post titled The only thing that matters, as part of the Pmarca Guide to Startups. It was ostensibly written as advice to startup technology companies, but in hindsight, reads like a manual to founding a16z. And it answered: which of the three core elements of a startup matters most – team, product, or market?

Entrepreneurs and VCs will say team. Engineers will say product.

“Personally, I’ll take the third position,” Marc wrote, “I’ll assert that market is the most important factor in a startup’s success or failure.”

Why? He writes:

In a great market—a market with lots of real potential customers—the market pulls product out of the startup…

Conversely, in a terrible market, you can have the best product in the world and an absolutely killer team, and it doesn’t matter—you’re going to fail…

In honor of Andy Rachleff, formerly of Benchmark Capital, who crystallized this formulation for me, let me present Rachleff’s Law of Startup Success:

The #1 company-killer is lack of market.

Andy puts it this way:

When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins.

When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins.

When a great team meets a great market, something special happens.

What I think Marc and Ben saw in venture capital was a great market (and no one appreciated how great) full of lousy teams (and no one appreciated how lousy).

Between 2007 and 2009, Ben & Marc were figuring out what to do next. They were very successful technology entrepreneurs, who, despite the success, had big chips on their shoulders, and who, because of their success, had the fuck you money with which to say fuck you.

But how?

As entrepreneurs, and then as angel investors, Marc and Ben dealt with a lot of shitty venture capitalists and they thought it might be fun to compete with those guys.

“For Marc, it was not about the money, at least from my vantage point,” David Haber told me. “He’s been rich since he was about 20. In the beginning, it was probably more about punching Benchmark or Sequoia in the face.”

Venture capital had another thing going for it, something that very few other people realized in the depths of the GFC-induced recession: it was perhaps the greatest market on earth. That mattered tremendously to Marc.

Of course, not all of venture capital was lousy. The two firms that Marc wanted to punch in the face - Sequoia and Benchmark - were excellent (Marc quoted Andy Rachleff!), aside from their proclivity for removing founders. And for those founders looking to stay in charge, Peter Thiel had launched Founders Fund in 2005 and was in the middle of deploying the 2007 vintage FF II that would go on to return $18.60 in cold hard cash (DPI) for every dollar invested, as Mario wrote.

But compared to today, on the whole, it was a lazy, clubby, hand-made industry.

There’s this story that Marc likes to tell about meeting with a GP at a top firm in 2009, when he and Ben were thinking about launching a16z, who compared investing in startups to grabbing sushi off a conveyor belt. According to Marc, this GP told him that:

The venture business is like going to the sushi boat restaurant. You just sit on Sand Hill Road, the startups are going to come in, and if you miss one, it doesn’t matter because there’s another sushi boat coming up right behind it. You just sit and watch the sushi go and every once in a while you reach into the thing and you pluck out a piece of sushi.

That was fine if the goal was to keep your good thing going, “as long as the ambitions of the industry were constrained,” Marc explained to Jack Altman on Uncapped.

But Marc and Ben’s ambitions were not constrained. There would be no greater sin at their firm than “missing one,” not investing in a great company. It mattered greatly. Because they saw that the big tech companies were going to get much, much bigger as their market grew.

“Ten years ago, there were only approximately 50 million consumers on the Internet, and relatively few had broadband connections,” Ben and Marc wrote in the Offering Memorandum for Andreessen Horowitz Fund I in April 2009. “Today, approximately 1.5 billion people are online, and many of them have broadband connections. As a result, the biggest winners on both the consumer and infrastructure sides of the industry have the potential to be far larger than the most successful technology companies of the previous generation.”

At the same time, it had gotten much cheaper and easier to start a company, which meant that there would be more of them.

“The cost of creating a new technology product and entering the market in at least a beta phase has dropped dramatically over the past ten years,” they wrote to potential LPs, “and now is often only $500,000-$1.5 million, as compared to $5-15 million 10+ years ago.”

Finally, the ambitions of the companies themselves grew as they transitioned from being tools companies to competing directly with incumbents, which meant every industry would become a technology industry, and every industry would get larger as a result.

This is why the market was so great at just that time. He went on to say:

From the 1960s through, call it, 2010 there was a venture playbook... the companies are basically tool companies, right? Picks and shovel companies. Mainframe computers, desktop computers, smartphones, laptops, internet access software, SaaS, databases, routers, switches, disc drives, word processors - tools.

Around 2010, the industry permanently changed... the big winners in tech more and more are companies that go directly into an incumbent industry.

Was a16z overpaying for companies in those early days? Or was it paying a good price relative to what it realized they could become?

In hindsight, it’s easy to claim the latter. What’s impressive about a16z is that they said the same thing in foresight.

If, as they wrote, the roughly 15 technology companies per year that ultimately reached $100 million in annual revenue generated approximately 97% of the public market capitalization for all companies founded in that year - the now-familiar Power Law - then they better do whatever it took to be in as many of the companies with the potential to be one of the 15 as possible, and then in a position to double and triple down in the winners.

And to do that, with just two investing partners, a16z had to think about how to build a firm differently than anyone else had.

So after sharing the basic terms of the AH I investment – $250 million target fund size, of which the General Partners would commit $15 million – Ben and Marc captured their firm strategy in a paragraph.

That is the strategy they are executing against to this day, even as the Firm has grown far beyond two partners and top 5 ambitions.

The Three Eras of a16z

Since that first fund, and throughout the Firm’s history, a16z’s outsized belief in the future, its asymmetric conviction, has been its core competitive advantage in my opinion. It is the point of differentiation that spawns all of the others.

How it has applied that advantage and chosen to differentiate has evolved over time, as the firm’s ambitions, resources, fund sizes, and power have grown.

First Era (2009-~2017)

In the First Era of a16z (2009-~2017), the core insight was that if Software is Eating the World, the best software companies would become far more valuable than anyone currently priced in.

This belief enabled a16z to do three things in order to move from new entrant to Top 5 firm:

Pay up for deals. As discussed earlier, a16z did deals out of its early funds that many others thought were too expensive or off-piste at the time. On the Acquired podcast, Ben Gilbert said, “The common knock was that they were overpaying to buy name brand for themselves to buy their way into winners,” but argued that it was both rational at the time, and noted, “Would anybody argue today that they actually paid too high a valuation for anything they did from 2009 to 2015? Absolutely not.” As Ben Horowitz explained in the 2014 HBS case study, “Even with multibillion-dollar valuations, investors might be underestimating companies’ potential.” That underestimation was a16z’s advantage.

Build operational infrastructure others called wasteful. Hiring a full services team, recruiting partners, executive briefing centers… all of this looked like overhead drag on a fund manager at the time. But if you believed portfolio companies could become category-defining and needed enterprise muscle to get there, the spend made sense. They were building for a future where startups needed to look like real companies to win Fortune 500 deals.

Treat technical founders as the scarce resource. It was also a bet that because companies were getting cheaper and easier to build, technical geniuses without traditional management chops could and would build more important companies. So it did everything it could to woo and support them, bringing the CAA model to venture. “Founder-friendly” is a meme now, but it was genuinely novel at the time.

Importantly, in this First Era, the most important thing was to just invest in the right companies and profit as they became as successful as a16z believed that they could. They were focused on helping the founders, to be sure, but mainly, they were taking advantage of an available arbitrage.

AH III, which had both Coinbase and Databricks, is a standout, but it’s worth noting the consistency.

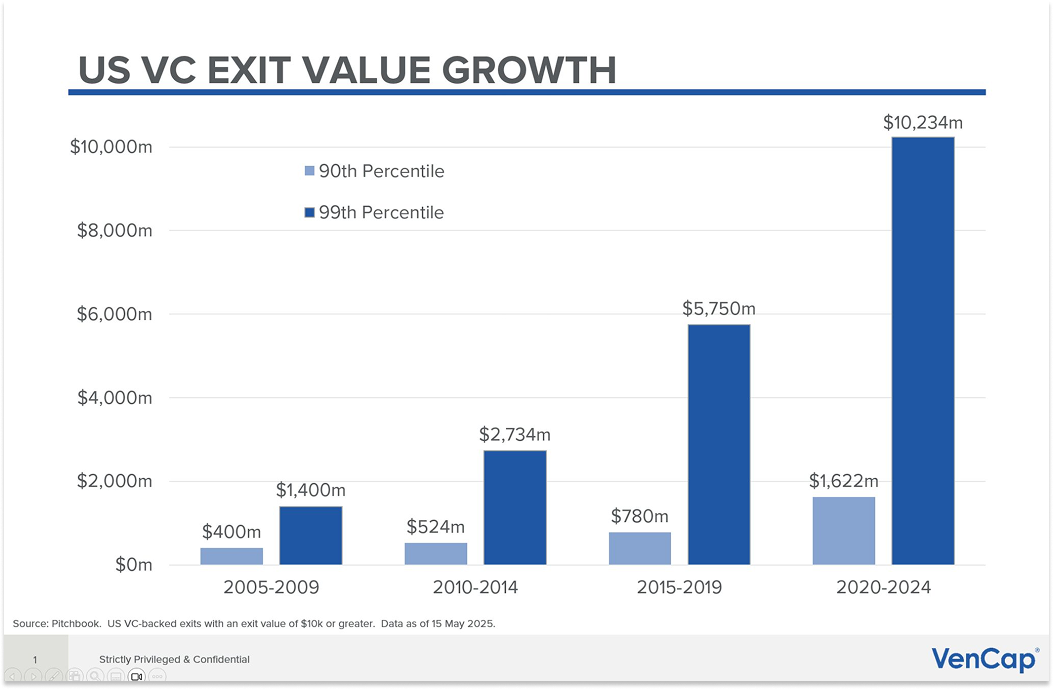

“As an LP we are happy with consistent [net] 3x [TVPI] funds with the odd one being [net] 5x+ [TVPI] and this is what they have delivered,” David Clark, the CIO at VenCap who has been an LP in a16z since AH 3, told me, “a16z are one of the few firms that have been able to deliver this performance at scale over a sustained period of time.” You can see that in the performance numbers above.

If this was the Era in which a16z was willing to pay up and “invest in pork bellies” in order to make a name for itself that would pay off over time, that trade didn’t seem to cost much in the short term.

Second Era (2018-2024)

In the Second Era of a16z (2018-2024), the key belief was that the winners were indeed getting much larger than anyone expected, they were staying private longer, and technology was eating more industries than others realized.

I think this belief enabled a16z to do three things in order to move from Top 5 Firm to Leader:

Raise larger funds. In the First Era, a16z raised $6.2 billion over nine funds. In the Second Era, over five years, a16z raised $32.9 billion over 19 funds. The standard VC wisdom was that returns degraded with fund size. a16z argued the opposite: if the biggest outcomes were getting bigger, you needed more capital to maintain meaningful ownership through multiple rounds. The worst things you could do were miss winners, and not own enough of the ones you owned. Marc is fond of saying that you can only lose 1x your money, but your upside is practically unlimited.

Build beyond a single fund. During the First Era, a16z raised core funds along with follow-on later-stage funds. All of a16z’s GPs invested out of the same funds, even if they each had their own focus areas. It also raised one Bio Fund, because Bio is a completely different beast. For purposes of this article, I am focusing on those a16z venture funds that are not focused on bio and heath.

In the Second Era, a16z began decentralizing. In 2018, it launched CNK I, a16z’s first dedicated crypto fund under Chris Dixon. In 2019, it recruited David George to lead a dedicated Late Stage Ventures (LSV) Fund and raised its largest fund to date: LSV I was approximately two times larger than any previous a16z fund at $2.26 billion. Through this period, it raised new funds across Core, Crypto, Bio, and LSV, as well as a dedicated Seed fund (the $478 million AH Seed I) in 2021, a dedicated Games fund (the $612 million Games I), and its first cross-strategy fund (the $1.4 billion 2022 Fund), which allowed LPs to invest pro rata across all of the funds in that vintage.

Importantly, while individual funds could tap into the centralized resources of the firm, like Investor Relations, each one designed its own dedicated platform team – marketing, operations, finance, events, policy, and more – in order to meet the specific needs of founders in their vertical.

Hold positions longer. During the Second Era of a16z, leading companies began staying private much longer and raising more money in the private markets, both primary (to fund the company) and secondary (to give employees and early investors liquidity). The practice that Matt Cohler compared to buying pork bellies when a16z bought late-stage secondary shares in Facebook became standard as companies like Stripe, SpaceX, WeWork, and Uber were able to access the same kind of liquidity in private markets that was previously only available in the public markets.

This created a challenge for the industry – LPs couldn’t get liquidity as easily, which gummed up the capital allocation cycle - but for firms that believed that tech companies were going to get much, much bigger, it was a godsend. It presented the opportunity to put a lot more money to work in high-quality companies that happened to be private, and pulled returns that would have accrued to public market investors into the private markets. I believe this shift is one of the key reasons that VC Firms like a16z have been able to get much larger without crushing returns.

In response, a16z did a couple of things. It became a Registered Investment Adviser (RIA), allowing it to invest freely in both crypto, public equities, and secondaries, and launched the aforementioned LSV 1 under David George9. During the Second Era, LSV raised $14.3 of the $32.9 billion raised across a16z’s funds. The Crypto fund also split into Seed ($1.5 billion) and later stage ($3 billion) for Fund IV.

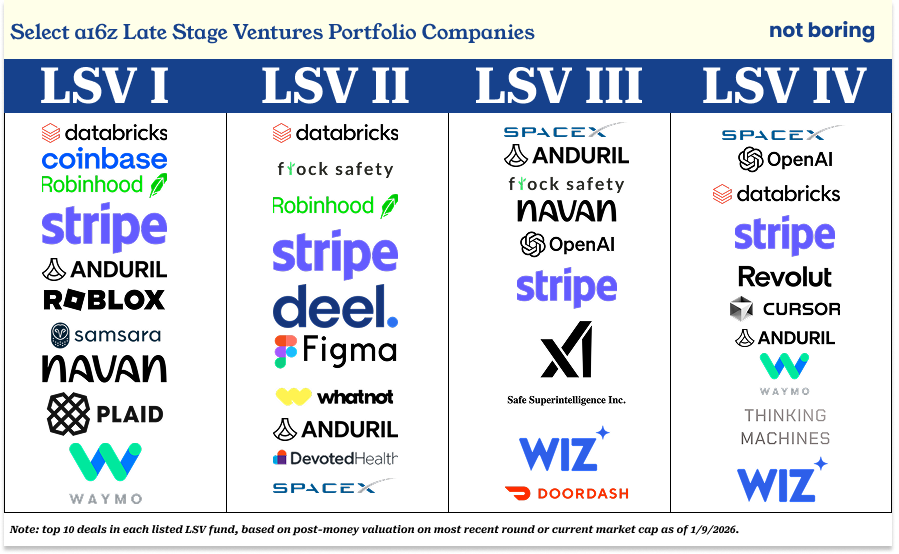

These are the top 10 deals in each listed LSV fund, based on post-money valuation on most recent round or current market cap:

LSV I: Coinbase, Roblox, Robinhood, Anduril, Databricks, Navan, Plaid, Stripe, Waymo, and Samsara

LSV II: Databricks, Flock Safety, Robinhood (which they exited in the public markets and recycled into more Databricks), Stripe, Deel, Figma, WhatNot, Anduril, Devoted Health, and SpaceX

LSV III: SpaceX, Anduril, Flock Safety, Navan, OpenAI, Stripe, xAI, Safe Superintelligence, Wiz, and DoorDash

LSV IV: SpaceX, Databricks, OpenAI, Stripe, Revolut, Cursor, Anduril, Waymo, Thinking Machine Labs, and Wiz.

If you were going to buy logos, as 16z has been accused of in the past, you could certainly do worse than these ones. That said, LSV I is in the top 5% of its vintage according to Cambridge Associates data as of Q2 2025, and both LSV II and LSV III are in the top quartiles of theirs.

As of September 30, 2025, LSV I was held at 3.3x net TVPI, LSV II was held at 1.2x net TVPI (although is likely higher now after Databricks’ and SpaceX’s recent fundraises), and LSV III is held at 1.4x net TVPI (also likely will be higher after SpaceX closes a major secondaries sale at a reported $800B valuation, up >2x.)

By believing that the outcomes for these marquee companies will be much larger than most (although certainly not all; see: Founders Fund and SpaceX, Thrive and Stripe) others believed, a16z has been able to put more money to work in the best private tech companies while they can.

Crucially, they’ve begun to show that it’s possible to achieve venture-like returns in a growth stage fund under the right conditions. Namely, based on analysis I have seen from one of a16z’s LPs, firms with strong early stage practices can deliver venture-like multiples (and higher IRRs) by continuing to invest at the growth stage. A deeper relationship with these companies, of course, can also increase the firm’s power.

In the Second Era, a16z believed the most important thing was to own as much of the winners as possible, which was easier to do if you knew the companies better from investing early and had dedicated late stage funds to continue to double-down, or correct early stage mistakes. (Although still not majority investments like you’d see in other asset classes.)

This, too, was an arbitrage, although I believe a16z did more to help its individual companies succeed in this era.

The returns from the Second Era are still early, but they are tracking ahead of where the First Era funds were at a similar stage in their life, when the WSJ reported on their underperformance.

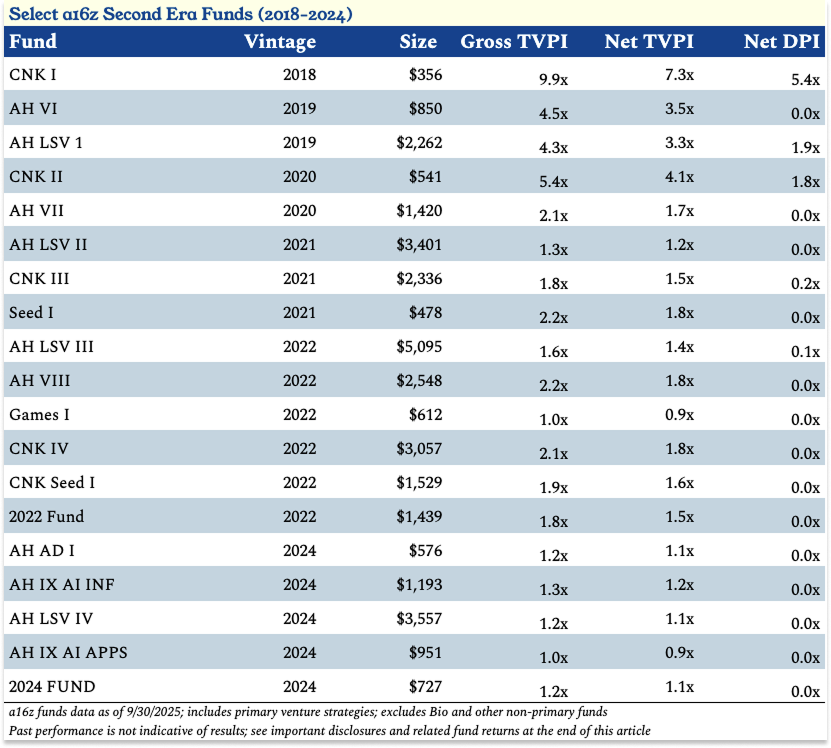

The 2018 funds are sitting at 7.3x net TVPI, the 2019 funds are sitting at 3.4x net TVPI, the 2020 funds are sitting at 2.4x net TPVI, the 2021 funds are sitting at 1.4x net TVPI, and the 2022 funds are sitting at 1.5x Net TVPI.

What is particularly notable in this era is the outperformance of the crypto funds (CNK 1-4 and CNK Seed 1). CNK I has returned 5.4x net DPI to LPs already.

Perhaps even more surprisingly to those who argued that a16z crypto had raised too much money in 2022 at the wrong time, the $3 billion it raised for CNK IV reflects (or “is carried at”) 1.8x Net TVPI to date.

The two biggest stories of this Second Era, LSV and crypto, speak to two facets of a16z’s belief in the future. LSV is a response to the fact that companies are staying private longer, and have greater private market capital needs. Crypto is a representation of the idea that innovation (and returns) can come from entirely new sectors than the ones you’re used to investing in.

They also speak to the need for a16z to expand what it does on behalf of its portfolio companies and the industry. In order to help its late stage companies thrive, it would have to recreate some of the benefits of being public in the private markets.

And in order to ensure crypto’s survival in the US, to ensure that new technology companies of all types would get a fair shake against the entrenched interests, it would need to head to Washington.

Which brings us to the Third Era of a16z (2024-Future), in which the key belief is that new technology companies will not only reshape but win every industry, if allowed to, and that a16z must lead the industry and the country in the right direction.

This belief is once again changing the nature of a16z. At a certain scale, and $15 billion in fresh funds is as good a line as any, picking winners isn’t enough.

You have to make winners by shaping the environment they compete in.

As Ben said, “It’s Time to Lead.”

The Third Era of a16z: It’s Time to Lead

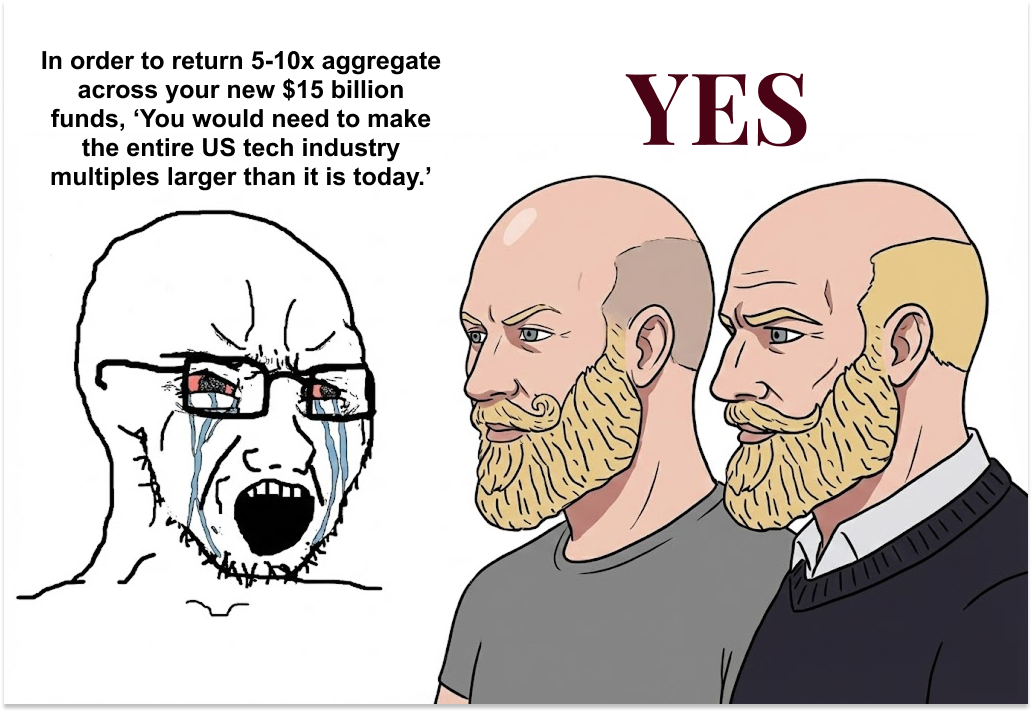

You might imagine, at this point in the game, an analyst at a rival VC firm texting journalist Tad Friend something like, “In order to return 5-10x aggregate across your new $15 billion funds, ‘You would need to make the entire US tech industry multiples larger than it is today.’”

To which Marc and Ben, you imagine, say: Yes.

That is the Firm’s explicit plan. Here’s the logic.

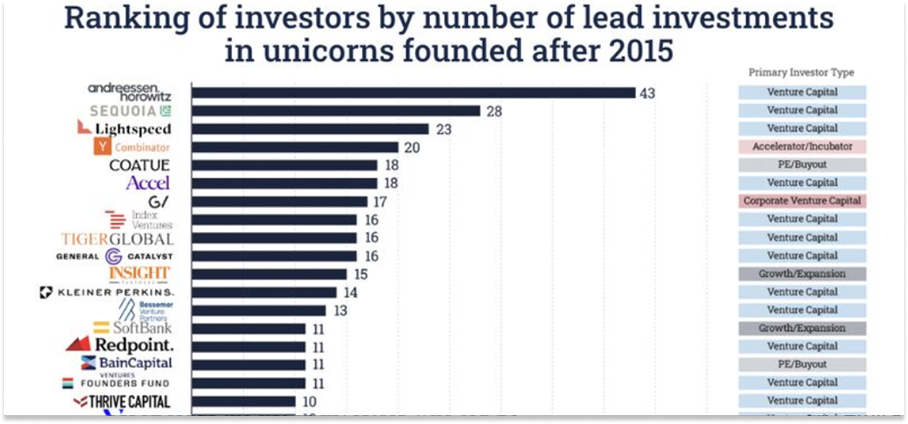

Since 2015, it has funded more unicorns at the early stages than any other investor, and the distance between a16z and #2 (Sequoia) is as wide as the distance between #2 and #12.

“Number of companies funded at the early stages that become unicorns” is, of course, a very specific and convenient way to judge “best.” More common would be to cite returns, by multiple or IRR or simply quantum of cash distributed to LPs. Others might point to hit rate or consistency. There are many ways to slice and dice a league table.

But this way seems to be consistent with how a16z views the world. As I heard repeatedly in my time with a16z crypto, betting on a category because a lot of smart entrepreneurs are building there and getting it wrong is totally OK. But picking the wrong company within a category, missing the eventual winner for any reason, is not. As Ben put it:

We know that building a company is a highly risky endeavor, so we don’t worry about investments that do not work out if we ran the right process when we made the investment and assessed the risks properly. On the other hand, we worry quite a bit about incorrectly assessing whether or not the entrepreneur was the best in her category.

If we pick the wrong emerging category, that’s no problem. If we pick the wrong entrepreneur, that’s a big problem. If we miss the right entrepreneur, that’s also a big problem. Missing the generational company either due to conflict or passing on it is far worse than investing in the best entrepreneur in a category we misjudged.

By its own estimation of what matters most, then, a16z has become the leader of the venture capital industry.

“So now what?” Ben asks. “What does it mean to lead an industry?”

In the X essay announcing this $15 billion raise, he answers: “As the American leader in Venture Capital, the fate of new technology in the United States rests partly on our shoulders. Our mission is ensuring that America wins the next 100 years of technology.”

This is a remarkable thing for a venture capital firm to say about itself.

It is also, if you accept the premises — that technology is the engine of progress, that America’s continued leadership depends on technological superiority, and that a16z is the largest and most influential backer of new American technology companies, with the power and resources to give them a fair shot against incumbents — not entirely unreasonable.

To win the next 100 years of technology (which, at a16z, is the same thing as winning the next 100 years, period), he continues, it must win the key new architectures - AI and crypto - and then apply these technologies to the most important areas, like Biology, Defense, Health, Public Safety, and Education, and infuse them into the government itself.

These technologies will make markets much larger. As I argued in both Tech is Going to Get Much Bigger and Everything is Technology, they mean that industries and jobs-to-be-done that were not previously in tech’s addressable market now are, which means that Venture Capital Addressable Value (VCAV) will increase dramatically as well.

This is a continuation of the bet that a16z has been making, but with a consequential twist on the belief: this value will be unlocked, and the future of America (and the world) safeguarded, if a16z does its job as leader.

Specifically, that means five things:

Make American technology policy great again

Step into the void between private and public company building

Take marketing into the future

Embrace the new way that companies will be built

Keep building the culture while scaling our capabilities

Nearly everything about a16z that makes you scratch your head is in service of these five things.

Most notably, a16z has gotten much more vocally involved in politics over the last two years, with Marc and Ben publicly supporting President Trump in the last election. That made a lot of people angry, and there is an argument to be made that a venture capital fund should not be influencing national politics.

a16z would take the opposite side of that argument, vociferously. It wants to Make American technology policy great again.

Marc and Ben laid out its argument in The Little Tech Agenda, which can be summarized as:

New technology companies are crucially important to our nation’s success.

In order to win the future, we need pro-innovation laws, policies, and regulations, and we must prevent regulatory capture by large, well-resourced incumbents.

The opposite has been happening: “We believe bad government policies are now the #1 threat to Little Tech.”

There is no one to fight for new technology companies in the halls of government or against incumbents: large incumbents won’t do it, startups shouldn’t spend their limited resources doing it.

Venture capital firms stand to benefit from new technology companies’ success financially, so VC should be the ones to fight this battle, and as the leader of the VCs, it falls upon a16z to do it.

a16z is a single-issue voter. Little Tech is the only thing it cares about. It is bipartisan.

These are talking points – “We do not engage in political fights outside of issues directly relevant to Little Tech.” and “We support or oppose politicians regardless of party and regardless of their positions on other issues.” – and they are, from everything I have seen at a16z, the absolute truth.

The Firm is not doing politics because it’s fun (although Marc, at least, seems to really enjoy the spectacle; he seems to really enjoy a lot of things, to find humor in the absurd, which is an underrated competitive advantage but one that we do not have time for today). a16z is willing to look stupid, and take arrows, in the short run to help new technology flourish in the long run.

For a very long time, as former Benchmark partner Bill Gurley argued in 2,581 Miles, tech could largely ignore Washington, and Washington could largely ignore tech. A few years ago, that changed, in part because of tech’s transition from making tools to fighting incumbents that I discussed earlier. Crypto was the first sector for whom this became existential.

When a16z first went to Washington, Little Tech was not a constituency in D.C. Large tech companies had their own lobbyists and relationships. Incumbents - banks, defense companies, whoever - had their own lobbyists and relationships. But Little Tech, including crypto, did not. No one firm, with the potential exception of Coinbase at the time, could afford the cost or groundwork it would take to represent itself in the nation’s capitol, let alone in state capitols around the nation.

So in October 2022, a16z crypto hired Collin McCune as its Head of Government Affairs, and Collin got to work educating America’s politicians on crypto. Collin, Chris Dixon, a16z crypto General Counsel Miles Jennings, other members of the team, and crypto founders, from in the portfolio and the industry more broadly, made repeated trips to DC to explain how crypto worked, what it could become, and more generally, the danger of regulating new tech out of existence.

And it’s worked. Thanks in large part to their efforts and the efforts of the industry’s bi-partisan Fairshake SuperPAC, crypto is not at existential risk from legislation. Last year, President Trump signed the GENIUS Act into law, which regulates crypto stablecoins for the first time, and comprehensive market structure legislation passed the House in overwhelmingly bi-partisan fashion. It is now making its way through the Senate with hopes of it passing and being signed into law later this year.

That experience proved valuable when AI became the hot button issue in DC. McCune now leads the Government Affairs practice across the Firm, with a permanent presence in DC and efforts spanning AI, Crypto, American Dynamism, and more. It is currently advocating for a comprehensive federal AI standard to avoid a mess of competing state regulations, among other pro-innovation policies.

While lobbying can be a dirty word, the fact of the current matter is that Little Tech’s competitors have sophisticated Government Affairs and Policy teams working to capture regulators and make it impossible for new entrants to fight on a fair playing field.

In order for tech to win the future, and for a16z to return its funds, staying out of politics is no longer an option. The good news is, as a Firm that needs new companies to form, grow, and win in order for its continued survival, a16z is as incentivized as any organization can be to keep the playing field open to innovation.

Because from the present moment, even a16z admits that it has no idea which companies are going to be built, or how, going forward.

Embracing the new way that companies will be built means being open to the idea that, with AI, entrepreneurs may be able to build companies with 1/10th or 1/100th as many employees as they could before, and that the things it takes to build a great company may be very different than what it’s taken in the past. It means that a16z needs to adapt, too.

So for example, it launched Speedrun, its own accelerator through which it invests up to $1 million and runs a 12-week program for nascent companies. This gives a16z early insight into how these new companies are being built and into each of the specific companies, so that it might be able to invest more in the winners more intelligently.

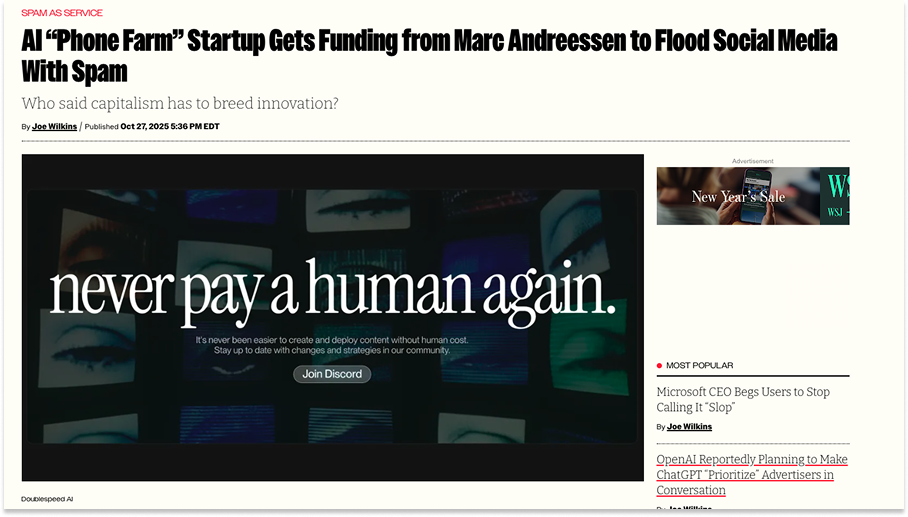

But it also comes with risk: increasing the number of companies that can say that they’re backed by a16z and lowering the bar risks dilution of legitimacy. For example, a16z has caught heat on twitter for Speedrun backing Doublespeed, which calls itself “Synthetic Creator Infrastructure,” but which others have called a “phone farm” and “Spam as a Service.”

The framing - “Gets funding from Marc Andreessen” - is funny, because Marc is not making sub-$1 million Speedrun application decisions – each Speedrun check represents something like .001% of a16z’s AUM. But that speaks to exactly the challenge. I’d seen references to this a16z-backed company a bunch of times on Twitter before guessing that they were a Speedrun company and looking it up to confirm. Most people won’t do that.

An more notorious example in a similar vein is Cluely, the startup that promised to help its customers Cheat on Everything, for which a16z led a $15 million round out of its AI Apps Fund.

People rightly questioned why a16z, a Firm that is actively working to shape America’s future, was also investing in a startup that valued virality over morality. Does the existence of a Cluely in the portfolio rub just a little legitimacy off of all the others, at least in the eyes of the Very Online?

Very possibly. Speaking personally, I didn’t love it. The vibes were off. It was unbecoming.

BUT! It was internally consistent.

Because beyond the actual product, what Cluely was pitching was that there was a radically new way to build a company in the Age of AI: one that assumed the underlying model capabilities were converging and commoditizing, that distribution would be the only thing that mattered, and that if it took a little controversy to get distribution, whatever.

If you are embracing the new way companies are being built, $15 million and a little Twitter controversy are a cheap price to pay for a front row seat to one of the most novel approaches.

More generally, in the business that a16z is in, looking stupid from time to time is the price you pay to avoid going the way of Kodak. You need to be willing to take risks, and taking risk does not just mean capital. At a16z’s scale, a little capital is the least risky thing to risk.

There is an argument to be made, though, that in the grand scheme of things, little blips on X (an a16z portfolio company itself) simply do not matter. Katherine Boyle, the a16z General Partner who co-founded the Firm’s American Dynamism practice, made that argument, in fact, when I asked her about it:

You could say that yes, maybe we take a few hits on Twitter because a company that people don’t like in a certain pocket of San Francisco or in New York or whatever don’t like it. Like, “We don’t like that they’re doing American Dynamism! We don’t like that they’re doing crypto!”

But the actual scale of the machine means that that little tiny blip in a moment just does not matter.

The best in class institutional comps are scaled systems. Something like the United States of America. Do we care when the United States of America does something embarrassing on a global stage? No, it doesn’t affect the United States of America, like it doesn’t affect the Holy Roman Catholic Church.

We’re thinking in centuries, not in tweets.

You might not agree with a16z on everything, but you have got to respect the balls on that Firm.

For what it’s worth, when I asked some of a16z’s LPs what they thought of certain Twitter-controversial companies, I was consistently met with blank “Who?”s.

The only thing that seems to have ever really mattered to a16z’s returns is the winners: finding them early, winning their deals, and owning as much of them as possible over time. Ask any a16z LP about Databricks; they know about Databricks.

Now, in the Third Era, the It’s Time to Lead Era, something that matters just as much is helping them grow, even as they get much larger.

This is what I think Ben means by Step Into the Void Between Private and Public Company Building, and I think it is the most critical reframing of how to think about a16z today, and about how it could possibly return 5-10x on $15 billion.

“In earlier days,” Ben said, “venture capitalists helped companies achieve $100,000,000 in revenue and then hand them over to investment banks for the next portion of their journey as a public company.” That world no longer exists. Companies are staying private much longer and at much larger scale, which means that the venture capital industry, led by a16z, needs to expand its capabilities to meet the needs of much larger companies.

To that end, the Firm recently brought on former VMWare CEO Raghu Raghuram in a triple-threat role - GP on the AI Infra team with Martin Casado, GP on the Growth Team with David George, and a Managing Partner and Ben’s “consigliere who will help [him] run the firm.” Along with Jen Kha, Raghu is leading a set of new initiatives to “address the needs of larger companies as they grow.”

That means working with national governments across the world to help portfolio companies scale and sell into their regions, forming strategic relationships with companies like Eli Lilly, with which it launched the $500 million Biotech Ecosystem Fund, and growing the number and depth of LP relationships worldwide. It means expanding the scope of a16z’s Executive Briefing Center, where large companies can meet directly with a custom set of relevant a16z portfolio companies.

Even for larger companies, there are things that it doesn’t make sense for each individual company to build from scratch, but that probably make sense for a16z to build and allocate across the portfolio. It just so happens that those things are at the level of governments, trillion dollar companies, and trillions of dollars in capital.

All of this could mean that companies can stay private longer without sacrificing the legitimacy, relationships, or access to capital that come with being a public company.

Which means that companies can grow to become much larger in the private markets, where they are squarely in a16z’s addressable market.

Which means that a16z has an opportunity to invest more capital with a reasonable chance of generating strong returns, which means the potential for more resources to invest in building more capabilities and more power, both of which it can lend to portfolio companies, and increasingly, to the entire new technology industry, in order to help bring to bear more and better new technology on more parts of the economy so that we can all have a better future.

There are, of course, many things that could go wrong. Mo Money Mo Problems. The leaders take the arrows. Etc.

The way I see it, I think a16z is playing the game at a different scope and scale than anyone has played it to date, with all of the opportunities and risks that entails.

More surface area means more potential vulnerabilities, for example. And the longer companies stay private, theoretically, the harder it is to generate liquidity for LPs, the harder it is for LPs to invest in the new funds that allow a16z to invest in the new companies that might one day be very large companies.

Ultimately, though, there are two constituencies that matter: founders and LPs, the Firm’s customers and its investors.

The Only Constituencies That Matter: LPs & Founders

How founders and LPs view the Firm, as expressed by who they take dollars from and give dollars to, respectively, is a compressed version of everything else I’ve discussed.

Here’s my logic:

If the best founders believe that all of the machinery that a16z has built will help them build bigger businesses than they otherwise would, they will take its money over another fund’s (or will at least make sure that it is one of the firms that it takes money from).

And if LPs believe that a16z continues to invest in the most excellent founders, they will give it money over other funds, and keep that money with them, even in the face of a liquidity crunch.

When I spoke with Jen Kha, she told me an anecdote that makes it clear that being in the very best companies is really the only thing that matters (other than being in the right market in the first place) in this game.

A couple of years ago, in the middle of that brief venture bear market, amidst liquidity concerns and the uncertainty of the early days of the Trump Administration’s stance towards endowments’ tax status, a16z offered them liquidity. To read the headlines at the time, including rumors that very blue chip endowments were selling off their venture portfolios, this was like offering water in the desert.

Specifically, Fund 1 had a Seed position in Stripe, and Fund III had a very large position from Databricks’ Series A. a16z went to its LPs and said, “We know you’re in a liquidity crisis. We would be willing to buy your interest in those names back if you would like to and figure out a way to get you some liquidity.”

“And literally, Packy,” Jen recalls, “30 out of 30 LPs said, ‘Absolutely not.’ They were like, ‘Thanks, but we don’t want liquidity out of those names. We want liquidity out of other names.’”

VenCap’s David Clark, an a16z LP, explained, “VC is not about early liquidity. It’s about compounding growth over multiple years. We don’t want our managers selling their best companies prematurely.”

Anne Martin at Wesleyan is one of those thirty early LPs and a testament to the power of compounding. She has backed a16z since Fund 1 in 2009, when she was at the Yale Endowment, and has participated in twenty-nine funds as CIO at Wesleyan. The new funds that a16z just closed on will bring it over thirty.

“a16z a very meaningful position and our longest-running in the portfolio that I underwrote,” Anne told me when we spoke last month. “It was one of two new managers I brought to my investment committee in our first meeting after I was hired.”

Having started the relationship by investing in a $300 million fund – “She directly negotiated the LPA [Limited Partner Agreement] with Ben,” Jen said – Anne agrees with a16z that the opportunity has expanded enough to support larger fund sizes:

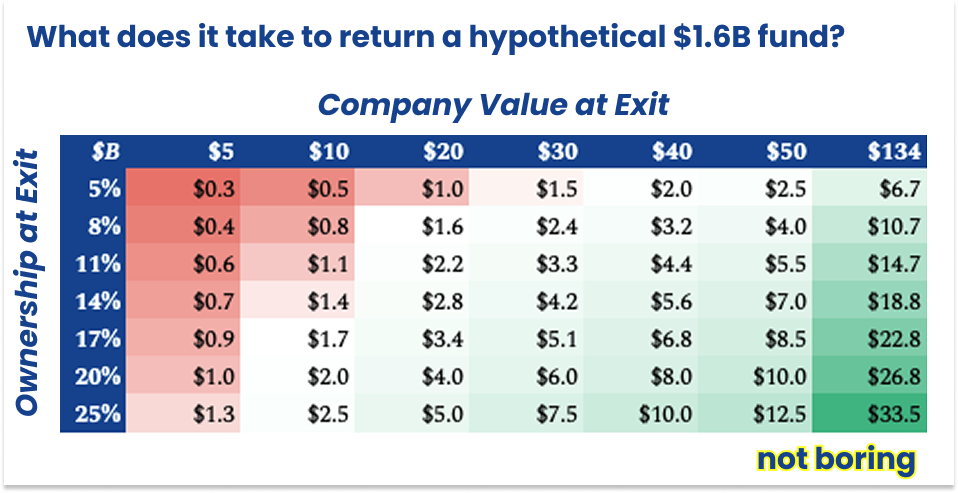

What’s interesting about Andreessen is... you take like a $1.6 billion10 fund for AI Infrastructure, and you build a simple matrix and you’re like, ‘Okay, let’s say they own 8% of a company at Exit…” What do you need from an exit to return the fund? If you own 8%, you need a $20 billion dollar exit. And you know, those are rare, but Andreessen seems to have quite a few of them. And the other thing that’s impressive is, like, is 8% the right number for them? Because a lot of times they have way bigger ownership.

“I think with them, it’s like the ownership and their ability to help these companies achieve a huge outcome,” Anne told me. “That’s what gets LPs comfortable with these fund sizes.”

That ability to help achieve huge outcomes is why even the most sought-after founders are willing to “charge” a16z less than its competitors. In several deals in 2025 alone, a16z invested at lower prices than other top firms investing in the same round. While it’s not right to share specific names, I heard of four investments in tech household names that followed this pattern last year alone.

Effectively, founders value the resources that a16z will bring that it can, at least occasionally, pay below-market today. That is a big change from the early days, when rival VC firms were so incensed at the prices a16z would pay that they nicknamed the firm “A-Ho.” It is a proof point that there is real, tangible value to working with a16z that companies “pay” for with higher dilution than they give other firms.

Which is to say, while I said there were two constituencies that matter, at the end of the day, there is really just one. I think if the best founders want to work with a16z, the best LPs will too.

Does a16z Improve Its Portfolio Companies’ Outcomes?

This is the question, huh? Some hypothetical formula that’s like:

% of market value attributable to a16z * market value impacted

And the tricky part is that to really have the biggest impact on the left-hand side of the equation, you have to be helpful when the right-hand side is smallest.

When you do that, though, when you help tiny companies become massive ones, you engender the kind of loyalty that means that founders are willing to say good things to you to other founders who are considering taking your money, and to people who are writing pieces about you.

When I asked Erik Torenberg to introduce me to a few of their founders, he connected me with founders representing over $200 billion in market value within hours, including Ali Ghodsi at Databricks and Garrett Langley at Flock Safety.

I bring those two up specifically because within 48 hours of our connection, Databricks announced that it had raised $4 billion at a $134 billion valuation, and Flock Safety helped catch the alleged Brown / MIT murderer. It was a visceral jolt of power.

What I wanted to understand, though, was how a16z applied its power on their behalf. Did it actually help shape outcomes? Did working with a16z meaningfully alter their trajectory?

Have the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars that a16z has invested in power infrastructure made a noticeable difference to the consumers of that power?

To believe in a16z’s Third Era bet, that it can expand the market for new technology companies and make its portfolio companies more valuable than they’d otherwise be in order to generate strong returns on $15 billion in fresh capital, you probably need to believe the answer to this question is yes.

The answer to this question is yes.

Recall that Ali at Databricks said there would be no Databricks without a16z. That’s $134 billion (and counting) added to venture capital’s addressable market, and ~$20 billion to a16z’s net returns in one fell swoop. Even if he is being hyperbolic, there’s an argument to be made that a16z’s support of Databricks – from early sales to the Microsoft partnership to support in building out specific departments – has paid back every dollar a16z has invested in its platform since inception.

In fact, lets say hypothetically a16z still owns ~15% of Databricks, back of the napkin math would estimate that Firm’s impact would need to account for something like 25% of Databricks’ value to have paid back standard VC management fees one could assume a16z has brought in since inception.

All of the founders I spoke with described a particular work style that’s consistent across a16z, no matter the GP you work with, that is clearly inspired by CAA: they stay out of your way and let you run the company, until you ask for something, at which point, they SWARM.

This is how a16z operates to win deals. The General Partners of each Fund decide what to invest in, and when they need to, they call in the rest of the Firm’s resources, including Marc and Ben, to win a deal.

“The firm at its best is delegated authority, delegated conviction, and group tackle,” David Haber told me. “Marc basically said, ‘Look, if you tell me this is the next Coinbase, I will fly anywhere in the world. I will fly that entrepreneur to have dinner at my house tonight. Get on the plane, pull out all the stops.’”

Once the deal is done, that is how GPs work with founders, too.

“They’re extremely supportive, no matter what. a16z, to a fault, has always supported me and the founding team, even when they didn’t see eye to eye with me. They’re not going to get in your hair on things that they shouldn’t be,” Ali told me. “But the second you need them, they’re all hands on deck, making it happen.”

And of course that’s how a16z is going to be with Databricks, but I heard the same thing from a few of my a16z-backed portfolio companies that are earlier in their journey, too.

Shane Mac, the CEO and co-founder of a16z crypto-backed messaging protocol XMTP, (appropriately) messaged me that “a16z does a ton of things. Like most VCs do. What I think matters more is what they don’t do:

They don’t tell me what to do. They don’t play short term games. They don’t waste my time ever. Every single connection they make, changes the trajectory of our business. They help me believe in myself more and realize that I too can build something so ambitious and we together can change the world.

I think that’s what they actually do the best. They believe in me and push me to realize I can do more than I ever thought possible.

Dancho Lilienthal and Jose Chayet, the founders of [untitled] (which I wrote about in late 2024 when a16z invested), shared a very similar experience, despite working with a different GP (Anish Acharya) on a different team (AI Apps).

A few weeks ago, they got on a Zoom catchup with Anish. They were nervous that their growth was compounding instead of exploding like the AI companies.

“We were scared that maybe an investor would be like, ‘Oh I don’t want to give them my time anymore because they’re just a slow burn’” Dancho recalled. “And Anish basically looked us in the eyes (remotely) and said: ‘Guys, the only way for me to not be here for you is if I die or if I get fired. I will be here no matter what.’”

This is how they describe the let-you-breathe-then-swarm approach:

They’re kind of like the most idealized version of a great parent. Really there for you when you need them and responsible for you and making sure everything’s good for you. And they’re not in your way and getting annoying when you don’t need them.

Which is beautiful. And by-design.

Joe Connor, the founder of Odyssey, the school choice platform backed by both a16z and not boring capital, said that he doesn’t go to a16z for day-to-day operating advice, but “Any time I need to talk to anyone, anywhere on planet earth, I can talk to them if I message Katherine.”

While it can put you in touch with any expert on any topic anywhere in the world, a16z explicitly does not want to get involved in its companies’ operations. In the 2014 HBS case study, Marc said, “We are not training wheels for start-ups. We do not do things for companies that they must be able to do for themselves.”

What a16z aims to do provide is legitimacy and power.

The Firm has provided a number of services over time, Alex Danco, who thinks a lot about these kinds of things, told me, “What are the most important services that we provide now? It’s hiring and it’s sales & marketing. Why those two things? Because that’s where you need the legitimacy bank. And the point of a16z is to be the legitimacy bank.”

Or, as Marc has said, “The thing you want from your VC is power.”

Joe gave me two examples.

A while back, when it was very small, Odyssey was having an issue with Stripe that it couldn’t solve through normal channels. “a16z got me on an email with Patrick Collison and it got solved immediately,” he said. “I’ve never been turned down when I’ve asked for something I needed help with. Stripe is worth like $95B, we were worth like nothing, but we’re all part of this a16z ecosystem and people pay it forward.”

Outside of the a16z ecosystem, the name still carries weight. Odyssey sells to state governments, whose employees probably could not name three venture capital firms or care less about them. But, Joe said, “They know a16z. They know Marc and Ben. And in the beginning, before we had a track record, before states could choose us based on experience, it gave states the confidence that we could do what we said we were going to do. That we had the better tech we said we did, because the people who backed Stripe and Instacart said we do.”

In October 2024, Odyssey won the contract to administer Texas’ $1 billion Education Savings Account (ESA) program, the largest in the nation. Now, it has its own legitimacy.

That is what it looks like to confer legitimacy, and it shows that legitimacy can scale. Legitimacy, to the vast majority of the market that doesn’t follow Silicon Valley closely, demands scale. The better a16z markets itself, the more legitimate its portfolio companies become in the eyes of potential customers, partners, and employees.

“If our firm does all kinds of great things and nobody knows about it,” Ben asks, in It’s Time to Lead, “did we actually do it?” Obviously, a16z is marketing to founders. They need to know what it can do for them. But it’s also marketing to everyone those founders might want to do business with in the future.

Marketing

Which is why it makes sense to build the best New Media team money can buy.

Some attention is cheap and derivative. The New Media team wants to make attention mean something. The team runs a full in-house media operation that builds and operates high quality owned channels (on X, YouTube, Instagram, and Substack), executes launches and timeline takeovers, and embeds directly with portfolio companies during critical periods.

“We are going through a bit of a PR challenge,” Flock Safety’s Garrett Langley told me a couple of weeks ago, before his company helped solve the murders at MIT and Brown, and at least for a little while, win back the PR cycle, “and while most of our cap table has ideas, a16z took action. Erik and his team jumped in. Literally. They are in our Slack now. They are in our positioning/branding docs. We just did a podcast with Ben this week. Having a trusted and respected brand, like a16z, come and stand up for what we do is critical for both the market and our employees.”

They are there when times are good, too, in those exciting early days. Fei-Fei Li, legendary computer scientist and founder of World Labs: “Four weeks before our Marble launch, their New Media team proposed an idea I had never seen before. They wanted to shoot our announcement video on a 3D LED volume stage, with our own product generating the environments in real time. They partnered with us on everything: the cinematic video, a behind-the-scenes documentary, a launch event, introductions to influencers in the VFX world. The launch went viral. We hadn’t built up our marketing muscle yet, and they helped us lay the groundwork for our operation. That kind of support, from creative vision to company building, is not something you find elsewhere..”

I am biased, because these are friends and long-time collaborators, but they are some of the very best in the business.

Erik has been obsessed with building new media organizations for a long time, which is why I turned to him to produce Age of Miracles. He’s also been obsessed with the idea that venture firms can have structural advantages.

Like, Erik and I had a chat about how he was thinking about building out the team, and never in a million years did I think he’d recruit Alex Freaking Danco.

If Writing is a Power Transfer Technology, and I clearly think it is, getting Alex Danco, and newer-hire Elena Burger, to write with and for you is an incredible superpower that money can’t buy. When every company is trying to hire a Chief Storyteller, a16z is just collecting them and spreading them across the portfolio.

Or, I first met Erik and David Booth when I did On Deck in 2019. No one in tech thinks about building community in the way that David does. Now, he gets to run what he’s learned with significantly more resources and access to the world’s best talent in order to attempt to make a16z into an even better “preferential attachment” machine and VC into a network effects business.

I realize that I’m gushing a bit here, and that a16z has tried to own the narrative in the past with initiatives like Future, which fizzled out, but 1) by the economic logic above, a16z should be taking 100 shots like Future and 2) this is the platform team I know best, because it’s what I do, and I wouldn’t have even thought these people were gettable. If that’s the level the other teams operate at, it makes me more confident that they really are building a machine with compounding advantages that companies couldn’t build on their own.

Every dollar spent telling the stories of the Firm and its portfolio companies is amortized in so many directions that they become a rounding error, and if all of those dollars, almost no matter how many a16z spends, mean winning and helping just one more Databricks, Coinbase, Applied Intuition, Deel, Cursor, or insert your favorite a16z company here, they’ve all been worth it.

That’s the economics a16z is playing with across everything. It’s the same logic the Firm applies to investing in startups - “The most you can lose is the dollar you invested, but your upside is practically limitless” - applied to everything the Firm does.

It makes more sense for a16z to build the best version of a thing that most of its portfolio companies will need (but is not core to those companies) than it does for any single company to, at least until it gets much bigger.

Hiring

Very tactically, the two things that I heard from every founder I spoke with is that a16z has been particularly impactful in two areas: hiring and sales.

Hiring has been a core part of a16z’s offering since the beginning, when Marc and Ben brought in Shannon Schiltz (Callahan) from Opsware, Shannon convinced Ben to hire Jeff Stump as Talent Lead, and the two of them built out a Talent Team that early stage money can’t buy.