Hardware is a Fruit

A Conversational Essay with Daylight's Anjan Katta

Welcome to the 494 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 255,469 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday! I want to try something new, which might grow into something bigger. A little seed of an idea, if you will.

One of the coolest parts of my job is that I get to talk to really smart people who are building products and companies based on the thoughts in their head. Sometimes, I write long essays on these people and their companies. Typically, the easiest way to get their ideas out into the world is by going on a podcast and yapping for an hour.

But there are a lot of ideas that deserve more than a passing mention on a podcast and less than a 10k word deep dive, and that are better expressed by the person whose idea it is than by me once-removed.

So I’m playing around with different ways to host those ideas, starting by co-writing an essay with Anjan Katta, the founder of Daylight Computer, on something he mentioned in passing when we were texting over the weekend.

If this series sticks around, Anjan will probably be a recurring voice. He’s one of the most original thinkers I know, and happens to be interested in a lot of the same weird stuff I am. I highly recommend his conversation with Jackson Dahl on Dialectic, the video he did with Jason Carman last year, and the conversation he had with Mario Gabriele and his mentor / computer legend Alan Kay.

I will also say that while I’m not an investor in Daylight, I bought one and I use it every day, and if you’re thinking of a Christmas gift for your favorite nerd… here.

If you buy one, you might just be supporting a world of much better software.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Silicon Valley Bank

We are living through of one of the most interesting periods in startup history. Revenue is growing faster, rounds are bigger, funds are bigger, and companies are burning billions. Some categories are red hot and others can’t buy a bucket.

That’s why I found SVB’s new State of the Markets H2 2025 report so fascinating. It highlights a complex and uneven recovery across tech. While some sectors are experiencing renewed growth, others face persistent challenges with stagnant deal activity, depressed valuations, and limited exits.

50% of VC-backed tech companies having less than a year of cash remaining. Series A companies burn $5 to generate every $1 of revenue. One-third of US VC investment has come from deals involving the six largest funds. Things are changing fast.

Hardware is a Fruit

A Conversational Essay With Anjan Katta

There is this challenge in software, and in capitalism, that new products, especially those designed to do anything but compete and win, start their life at a disadvantage, like naked seeds.

An example. Last week, my friends Alex Komoroske, Aishwarya Khanduja, and collaborators released the Resonant Computing Manifesto.

“Regardless of which path we choose, the future of computing will be hyper-personalized,” they write. “The question is whether that personalization will be in service of keeping us passively glued to screens—wading around in the shallows, stripped of agency—or whether it will enable us to direct more attention to what matters.”

Their vision is the good future, and the question they ask is an important one, one that I’ve been writing about. I signed the Manifesto. I want to see the future go the way they do, as I suspect most of us do.

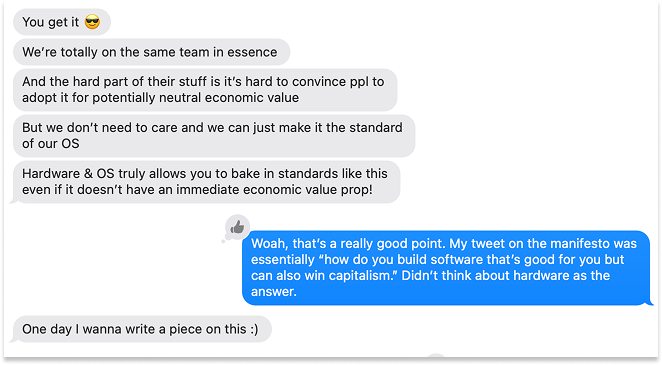

But there’s a chasm between writing a manifesto and seeing it manifest. I tweeted, “This is going to be one of the most fascinating things to figure out in the next few years, how to build software that both wins capitalism and is good for us.”

That was a myopic framing. This isn’t a next few years thing, although AI makes it more urgent. This is a forever thing, an always has been thing.

This is one of the tensions at the heart of capitalism: the market doesn’t account well for externalities, negative or positive, and so trying to do the “right thing” is disadvantageous.

If a social media product gets the most people to spend the most time in it, it wins. It is not penalized for brainrot and depression. Brainrot and depression are just negative externalities, borne by society.

But what if we all agree those are bad? And social media developers decide, hey, we’re not going to do that bad stuff anymore? What if we all decide just to do the good thing, the Resonant Computing thing?

This is the subject of one of the internet’s greatest essays, Meditations on Moloch. Multipolar traps, situations in which everyone is competing against everyone else, lead to races to the bottom where no one can unilaterally stop even when everyone agrees the outcome is bad. Everyone cooperates until someone takes advantage of those soft goody two-shoes, makes the brainrottiest version of all, and steals all the customers.

“Good for you” stuff, stuff with positive externalities usually gets its ass handed to it in the market. There are no healthy snacks in the top 10.

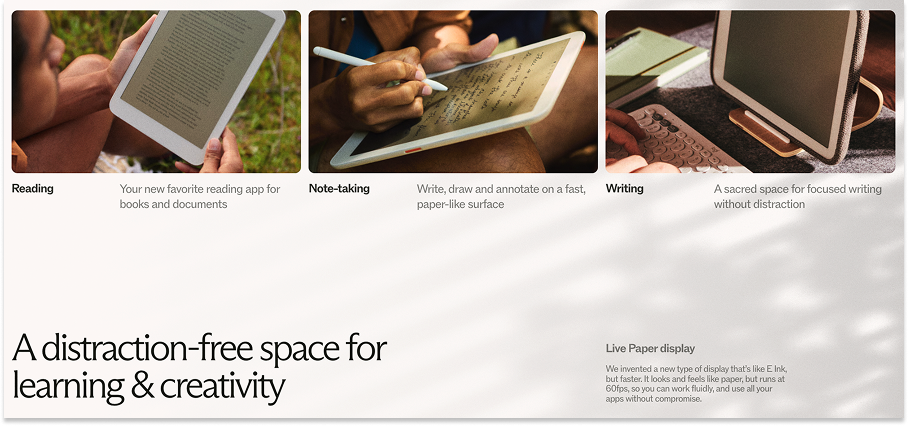

Anjan Katta, the CEO of Daylight and one of the most individual thinkers I’ve met in tech, has been thinking a lot about this problem. A lot. For seven years, as he’s built Daylight Computer, “A new kind of computer, designed for deep focus and wellbeing.” It’s sort of like if Kindle and iPad had a baby, to do computer-y things you can feel good about.

Anjan texted me when he saw that I signed the Manifesto like he did. We got to talking, and I realized that Daylight and the Resonant Computing movement go together like apples and seeds.

This whole essay is based on his ideas, kind of a mashup of the thoughts he’s mined over seven years and my forcing them onto the page.

What I learned from Anjan is that one point of hardware is to be a fruit.

Consider the apple: an apple tree wraps its reproductive code (the seed) in an animal-tempting package (the fruit). The seed rides along for free, gets distributed, and only needs to get to work once it’s already in fertile ground, later. Nature asks no one to value the seed.

Hardware can play a similar role for new software.

Right, and so the problem with trying to do the right thing, as Anjan explained it, is that a lot of well-meaning companies have tried to build defaults into their software that ultimately have positive externalities, that are pro-social, and either those companies fail or they throw out the defaults for more competitively fit ones.

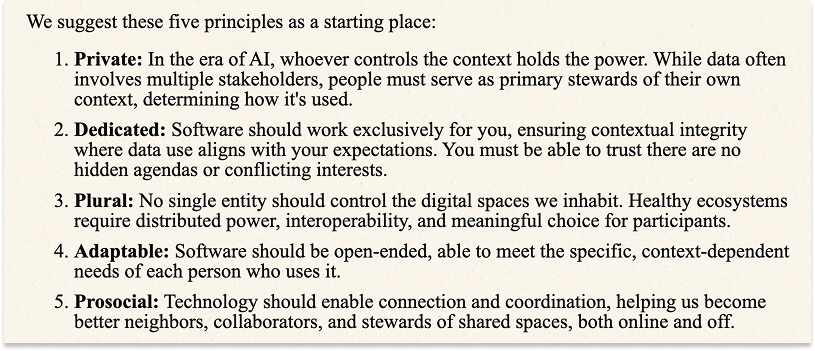

By the “right” thing, here, the “good for you defaults,” we mean those like the Resonant Computing Manifesto’s five principles: Private, Dedicated, Plural, Adaptable, Prosocial.

These “good for you” defaults tend to fail on their own because in the short-term, they cost more than they’re worth to the people deciding whether or not to use them, namely developers and customers.

Take privacy. There is a dedicated mausoleum in the startup graveyard for companies that have tried to compete on privacy alone. Ensuring privacy, and security, costs friction, and the people vote with their thumbs: the cost today isn’t worth the maybe one day benefit. “123456” is still the world’s most common password.

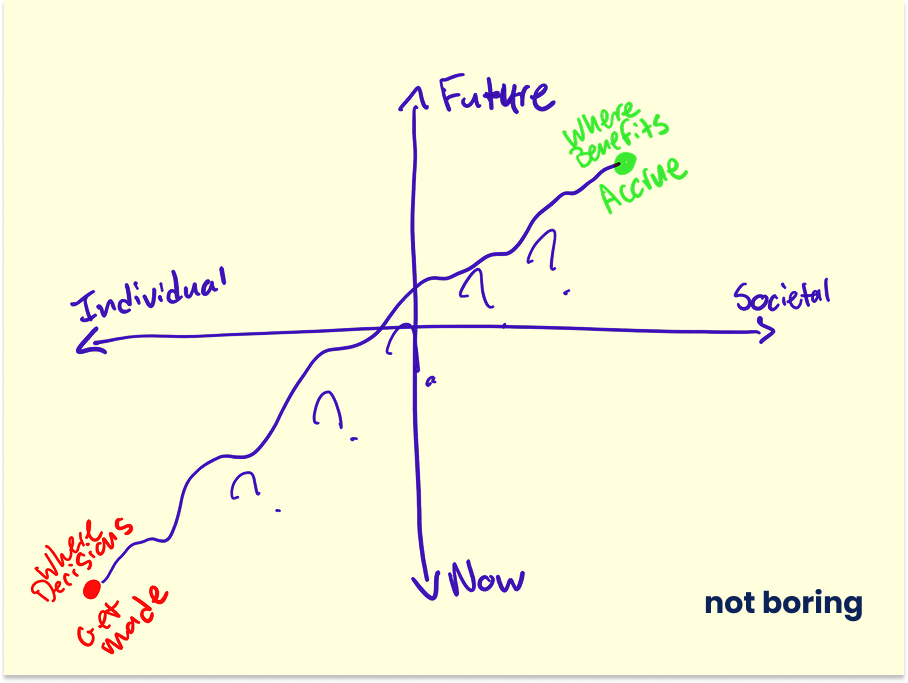

The challenge for good-for-you defaults is that the people who benefit aren’t the people who decide. Decisions are immediate and individual; benefits are long-term and societal.

It’s not that people don’t want Privacy or Adaptability. All else equal, they do! It’s that the promise of their future benefits isn’t strong enough to overcome their costs today, for most people, the same way that you would have a hard time convincing a bear to disperse apple seeds by paw even if it might mean delicious apples one day in the future.

Which is why evolution created the apple, and why Anjan thinks hardware can bridge the gap for good-for-you software.

For one thing, hardware provides activation energy and overpowers friction.

People will buy hardware because it’s new and shiny and bold, because it does something very specific they want to do (or says something very specific that they want to say about themselves). They will often pay a lot of money for good new hardware, at a good margin.

A screen with no blue light and a high refresh rate is so valuable to certain customers that they’re willing to trade a little software friction to get it.

Hardware allows you to solve the problem of resonant software not providing a benefit for the user immediately, it not having a benefit for the dev immediately, and being able to survive the valley of death that is the three to five to seven, 10 years before this actually serves to accrue value for your ecosystem, for your community, for the customers, for the devs, whatever it may be.

Come for the hardware, stay for the software. Come for the “don’t rot your brain with blue light,” stay for all the other stuff.

“And that to me is the sort of a-ha moment of what we’re doing at Daylight,” Anjan voice memo’d from El Salvador.

Hardware generates cash flow, too.

The reMarkable tablet, the predecessor to Daylight, does around $400+ million in revenue at ~50% margins. You don’t have no 5G, you ain’t got no titanium, you ain’t got no A19 crazy processor. And you know, those are the most expensive parts of a computer. And so…

That’s $200 million of annual cash flow, up for grabs from reMarkable, but probably many times more than that because Daylight does more than reMarkable, does it better, and expands the market. You could imagine kids using Daylight as their first computer. Maybe $1 billion in cash flow a year eventually? More? Whatever the number, all that cash can support the software ecosystem as it develops enough to stand on its own two feet.

Which means customers don’t have to notice underlying protocols, because they’re not paying for them. They’re not making that decision. It’s bundled into the hardware purchase.

The cool part of hardware is I don’t need to gain revenue from the particular software because what I’m ultimately playing for is to build the next ecosystem, right?

And it’s like what Jeff Bezos says, your margin is my opportunity. I’m like, your negative externalities are my opportunity.

In the longer-term, I think society is going to orient in that way. And it will ultimately then be best for the customer and for business, not just in general for society. But for all three. You just need to have enough patience to be able to get to that.

Hardware provides the bridge, crosses the chasm, seeds the future.

Hardware, this beautiful fruit, can be differentiated, 10x better on some dimension, in a way that’s very hard for software to be at this point. You can put hardware under the Christmas tree, too, which is to say, people are used to paying for hardware and getting a thing.

So hardware can be this carrier that generates enough cash flow to sustain both itself and the software it’s carrying until, in the longer-term, the initial bet, that a mature ecosystem built on those principles is actually better once it matures, pays off.

At which point, you have been spending years building this vertically integrated user experience, which should mean a better user experience, because the more dimensions of reality I have access to, the better I can make the UX, over time.

Because hardware gives you access to more dimensions of reality.

This is all a bet of course, but one with positive EV. If the software bet is wrong, you still have the differentiated hardware; you can still run Android. If it’s right, your devices become synonymous with technology that works for you.

Even though “hardware is hard,” building hardware makes a lot of other things easier, once you’ve done it. It would be structurally very difficult, at this point, to do any of what we’re describing as a venture-backed software startup alone.

It would be hard for anyone to do this alone, because it is an ecosystem.

And hardware can serve as a physical home to a new digital ecosystem.

Hardware overcomes the immediate consumer benefit problem because people like buying great new hardware.

That helps overcome the immediate developer benefit problem, because developers want to build where the customers are, and where customers will notice them.

Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store are so unbelievably saturated that it’s practically impossible to stand out, even if you’re building something genuinely better than what already exists.

On Daylight, there is very little competition and direct access to all these Daylight users who, if they’ve spent a bunch of money to buy this thing, they’re basically all people who are willing to pay for a particular type of experience.

If you haven’t used a Daylight, what is that experience? It’s calm, humane, resonant, Anjan uses the word “poetic” and it works. It has this gentle orange glow. I use it to read and take notes and think and it doesn’t grab at me to do more when I’m done doing those things. It’s trying to do in hardware what Resonant Computing wants to do in software.

It’s less noisy, by design, so Daylight becomes a really attractive place where the developers of new software who face incumbent distribution advantages and straight noise on existing platforms finally have a chance to compete on product quality on the new platform. It’s a very attractive proposition if you’re the reader app number 52, if you’re the meditation app number 66, if you have a great app that just can’t compete in the noise of the existing app stores.

And because of that, Daylight can get developers to build on good-for-you defaults.

Daylight offers the normal Google Play Store, the people want what the people want, but for any dev who wants to develop for Daylight specifically, as part of the base SDK, as part of the base set of standards for developing in Daylight, you can ask them to implement this protocol.

And sure, maybe there’s some friction to do that. But as long as the customer experience doesn’t suffer, it’s not a big ask to developers: adopt these defaults to reach Daylight’s customers.

Those customers won’t know or care what’s under their software in their new hardware in the beginning, and they don’t have to. No one thinks about the seeds, but they do spread them, give them the chance to grow.

Even if immediately there is no value prop to the user, we can have basically a ton of people with apps that have this underneath. And slowly over time, maybe it gets revealed to the user.

Maybe it creates interesting emergent behaviors. Maybe it creates certain AI workflows and use cases and applications that are really useful. Right? All the things that Alex is trying to do with Common Tools.

I think in a couple years, we’ll be able to create fun, new user experiences. And I can survive until then. The point is I’m not dependent. It’s not a dependency. It’s an optionality.

I’m able to make that work because I’m getting my cashflow from hardware and I think it’ll be better for customers in the long run, a better user experience than anywhere else, and so, yeah, I think that just allows us to solve a canonical set of problems here.

It’s really straightforward, but I don’t know if you don’t take this approach, that you can do this.

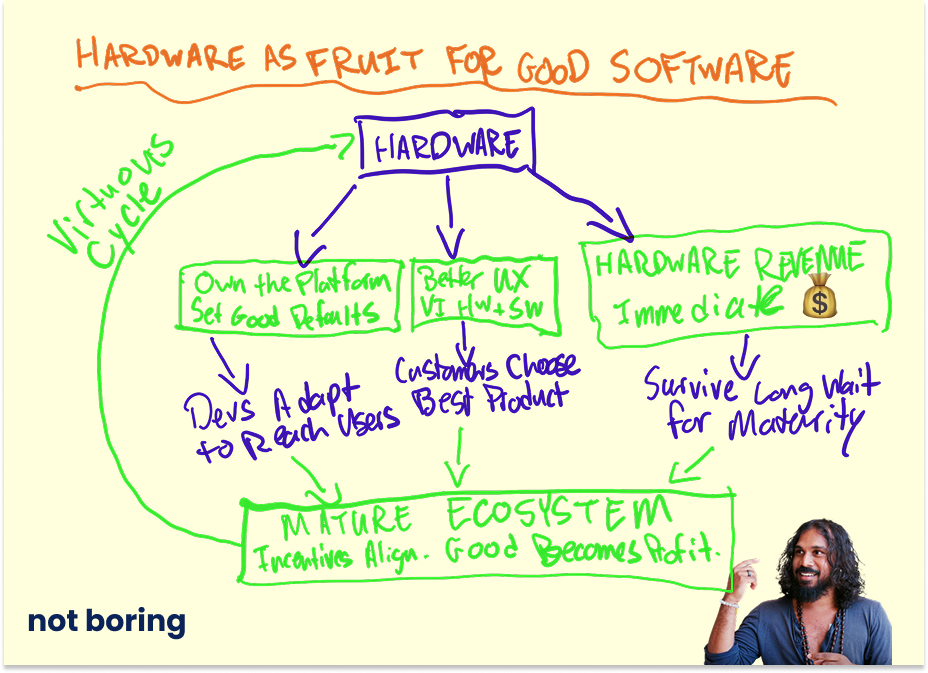

Hardware is a fruit, a delicious carrier of fragile seeds that might one day grow into something delicious themselves. Anjan’s logic flows a little something like this.

Hardware lets you do three things: own the OS, create a better UX, and generate hardware revenue.

Owning the OS means that you get to set the standards for your ecosystem, which developers adopt if they want to reach your customers. Your customers are there because, by building hardware and software, you’ve built a product that is meaningfully better for them on things that matter to them. And because it’s hardware, they’re willing to pay cash now, which means that your ecosystem can survive until it matures.

Of particular importance, that cash represents the fact that customers are paying the hardware manufacturer to do a job for them. If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. If you’re paying for the product, the product is the product!

Which means that the hardware revenue isn’t funding the ecosystem out of altruism, but in order to deliver the best version of the product that customers have paid for, even if it takes time to come to fruition.

This is a bet that compounds over three, five, seven, ten years. You can bake in constraints and incentives that are genuinely healthy for users and society, even if they don’t pay off this quarter. Healthier defaults → better apps → better UX → a stronger ecosystem that eventually throws off huge economic value.

The endgame is a business model built on aligned incentives, not exploitation. Users, developers, and the company all benefit, and the platform generates positive externalities for the world.

In short: you can be more idealistic with your software when the hardware is paying the bills.

What we’ve discussed in this essay is a specific category of solution to a specific category of problem: how to give software that has short-term friction and long-term benefits the chance to bloom by wrapping it in hardware.

But I think it applies more generally, which is why we wrote it.

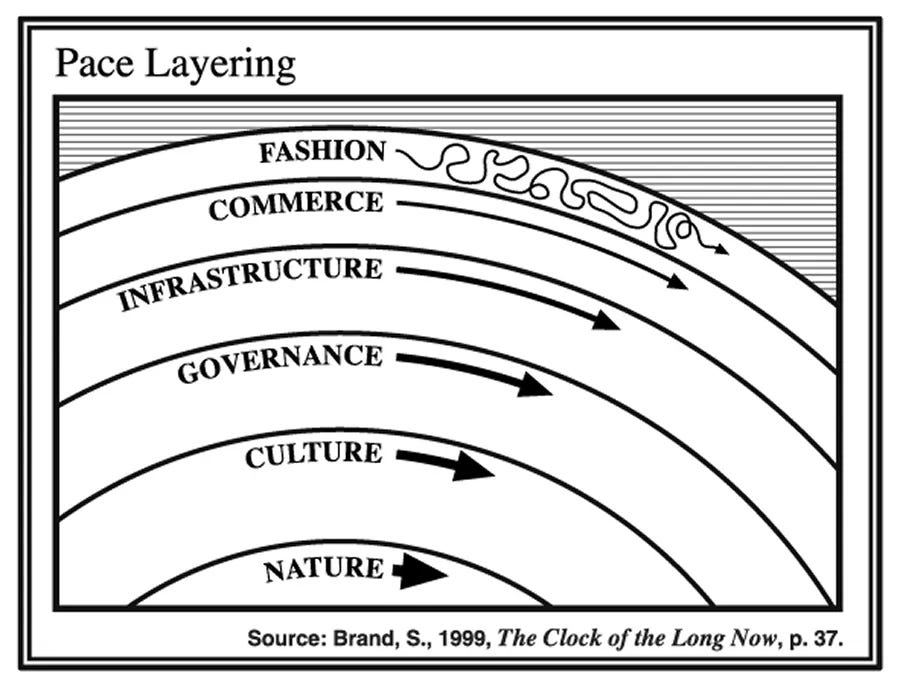

It’s Pace Layering. Hardware is the nature layer, a firm base that creates room for freedom and experimentation at the higher layers.

And it’s an exploration of how to fight capitalism with capitalism, or how to give the future and society a say in decisions made today by individuals.

That’s one of the most fascinating questions in the world to me. If you believe that capitalism is one of humanity’s greatest inventions and that it can be improved, small improvements can have a massive societal impact.

It’s why I’ve been so fascinated by crypto: can you program incentives into software to overcome the mismatch?

There’s something beautiful about the idea that hardware is a potential solution.

It’s hard. It’s slow. It’s expensive. But because of all that, there’s less of it. It’s easier for hardware to stand out. The people who want it are willing to pay for it.

Building your own hardware gives you room to improve on every piece of its stack.

For Vertical Integrators, that might mean building hardware in order to write your own firmware, software, and OS, so that the whole system works perfectly for your specific use case. As Alan Kay, who is mentoring Anjan and Daylight, said: “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.”

But in software, we’ve seen that ecosystems build better apps than any single hardware maker can. You run very few Apple apps on your iPhone, I bet. Knowing that, the smart move, and the prosocial one, may be taking some of your hardware credit and gifting it to the ecosystem, to bootstrap it into what you want it to become.

There’s a built-in plurality to this approach, too. Hardware doesn’t scale into every nook and cranny the way that hyperadapted software can. Each piece of consumer computing hardware can develop its own little ecosystem, almost physically, like little countries running competing economic and governance experiments. America had to control its own hardware before it could throw out British software and write its own.

Best, none of this requires anyone to do anything they don’t want to do, now or in the future. The bear doesn’t need to care about the seed. He just needs to desire the apple. The rest of this shit flows from there.

Thanks to Alex and Aishwarya for the Manifesto that sparked this, and to Anjan for jamming.

That’s all for today. We’ll be back in your inbox tomorrow with a Weekly Dose.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

This is maybe the most exciting essay on tech I’ve ever read and crystallizes so many thoughts and feelings I have had around tech that have only really come into focus the last year or so. It makes me super excited about a future in which tech is additive to life instead of brain-rot inducing. The vibe shift is already underway and it’s a “you can just do things” attitude. Like, you can just build tech that doesn’t induce brain rot. “Your negative externalities are my opportunity” is the key. So ripe for this. In a perfect world, trust and integrity will become key competitive advantages.

“Owning the OS means that you get to set the standards for your ecosystem, which developers adopt if they want to reach your customers.”

There are so many banger quotes in this article, but this one has a ton of potential. I know the people want what the people want as it pertains to things like Google Play Store, but I wonder if that will also change at some point. Nobody needs access to 2 million apps. In that sense, users are almost defenseless against the paradox of choice. It’s anti-productive. I think it’s possible to have exclusivity and curation as a value proposition at some point. Where you have a set of values and standards, and as you say, developers must adhere to those to have a place on your hardware/OS. Thus, to reach your customers. It’s the best form of competition that will hopefully produce completely different products than what is mainstream now.

Basically: Thou shalt not exploit the user.

But I can envision a future in which people think it’s crazy that we subjected ourselves to a non-curated firehose of content. And I think curation can still achieve a non-censorial approach in the sense that 200 or 2,000 apps are better than 2 million, and in those curated selections, you still have access to basically everyone in the world’s ideas and thoughts should you want to find them. But it’s devoid of slop and devs/apps that engage in deliberate brain rot tactics. Like, that can become a norm.

Maybe the competition also then becomes who has the best curation process embedded in their OS/hardware. Who has the best suite. People can critique an OS if it’s discovered that they have some sort of obvious ideological bent. Or critique others if it’s found out they basically just engage in “pay to play” curation.

It’s competitive in the best way. Developers have an entirely new incentive structure that is grounded in something much more meaningful than “let’s get the user to use our app for as much time as humanly possible”. It actually becomes, “how can we help”.

Basically, the biggest risk/barrier here is human folly and selling out to something that is in its nature "bad". Which will probably happen if creators have no connection to something transcendent. Needs to be connection to the ideas you put forth in your Means and Meaning piece.

Just bravo. This is so good. Fingers crossed this all comes to fruition and a better future awaits!

Another quote could be, "Companies who are serious about mental health should make physiologically aligned displays ."

You can't app your way out of hardware constraints. Most people believe apps are addictive. That social media is the problem. But this is like blaming fast foods for being unhealthy while ignoring the processed ingredients. Any fast food made with the right ingredients can be nourishing. A burger made with hyperpalatable (fat carb ratios) processed ingredients triggers overconsumption.

Displays are either hyperpalatable or satiating. Current screens are optimized like processed food. Engineered to be impossible to stop consuming. The physical sensation of looking at most displays is activating. The refresh rates, the color saturation, the brightness curves are not natural. They're the digital equivalent of added sugars and seed oils, designed to override your body's natural satiation signals.

We overconsume social media not because the content is irresistible, but because the display makes it impossible to feel satisfied. The form factor becomes turns you into Eddie Brock (succumbing to your digital symbiotes need). The haptic feedback is engineered for compulsion. No "digital wellbeing" feature or app can overcome this. Have you ever seen someone who uses a timer for IG? It useless friction.

If we're serious about solving the mental health crisis in computing, we need to rebuild from the photons up, the hardware layer. Not better apps on toxic displays but displays designed for satiation rather than endless consumption.

The moat is the ethical foundation that compounds into the future. Tech giants actually can't compete.

Not because they lack resources or talent, but because their foundations carry the burden of irreversibility. Apple and Google made optimization decisions 30 years ago—blue-light displays, engagement-maximizing refresh rates, form factors designed for constant access. . They can't uproot the foundation without invalidating everything built on top. Apple will be like Applebees. In the early 2000's Applebees tried to upscale and lost customers. This will be the faith of big tech if they try to compete on display tech..

Daylight's moat is now. The opportunity to build the foundational layer based on what society actually needs in the present.

1. Displays for wellbeing,

2. Hardware for satiation,

3. Architecture for human flourishing.

That choice compounds forward (like the doodle shows) into which apps succeed, developers thrive, and users stay (value-prop being they don't become retarded). The ethical constraints become structural advantages that deepen with time.

Start with the right foundation today, and every layer built on top inherits those principles as advantages. Start with the wrong foundation decades ago, and every attempt at reform collides with the architecture that made you successful.

That's the moat: being right at the foundational moment, while others are trapped by being first.

Towards a better future!

Great job Anjan