The Electric Slide

The history, 99% decline, and future of the Electric Stack with Sam D'Amico

Welcome to the 1,269 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 248,515 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Tuesday! Been a minute.

A month ago, I caught up with Sam D’Amico, the founder of Impulse Labs. We got to talking, and decided to write something together on the modern electric tech stack.

It would be simple, I thought: a few graphs showing how much the cost of the stack has declined over the last few decades (99%, it turns out), a few stories about demand for certain products driving those cost reductions, bada bing, bada boom.

One month, over 100 hours of research and writing, and 40,000 words later, it’s done.

Sam has been evangelizing the Electric Stack, and it’s resonating. Just yesterday, Ryan McEntush at a16z published a great piece on the Electro-Industrial Stack that discusses some of the topics we talk about here. We need more: that there are hundreds of books, thousands of essays, and millions of tweets on (and by) AI and so few on this topic is a reflection of American priorities that will need to change.

This essay is my contribution to the conversation. It goes deep into the history of the Electric Stack, introduces the Electric Slide, wrestles with the strategic logic of betting the future on AI, and ends with cautious optimism about America’s ability to rebuild and win in the Electric Era.

If you want to jump straight to the online version: Read The Electric Slide Online

And if you want to listen to this essay, check out the audio on ElevenReader (by ElevenLabs) here.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Vanta

Vanta helps growing companies achieve compliance quickly and painlessly by automating 35+ frameworks, including SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, and more.

Start with Vanta’s Compliance for Startups Bundle, with key resources to accelerate your journey: step-by-step compliance checklists, case studies from fast-growing startups, and on-demand videos with industry leaders.

The Electric Slide

One of the more interesting developments in AI is that while the American AI companies are mainly focused on closed-weight models, China is building open-weight models.

That begs the question: why?

On its face, the bet is simple: if China doesn’t have access to leading-edge chips, then open-weights are the best way to encourage both adoption and ecosystem development.

I think they’re making a different bet.

A couple of years ago, Isaiah Taylor, the founder of nuclear company Valar Atomics, told me something that’s stuck in my head ever since:

There are only really three pillars to anything around us, as far as consumable goods. We've got energy, intelligence, and dexterity.

I would generalize “dexterity” to “action.” Everything we see around us, and will see around us in the future, is the result of the potential to do work (energy), the capacity to decide what to do and how (intelligence), and the ability to manipulate matter (action).

In economic terms, energy, intelligence, and action are strong complements in the production of anything.

And in the immortal words of Joel Spolsky, "Smart companies try to commoditize their products’ complements.”

America is, implicitly or explicitly, making a bet that whoever wins intelligence, in the form of AI, wins the future.

China is making a different bet: that for intelligence to truly matter, it needs energy and action.

If you control energy and action, making intelligence abundant strengthens your position.

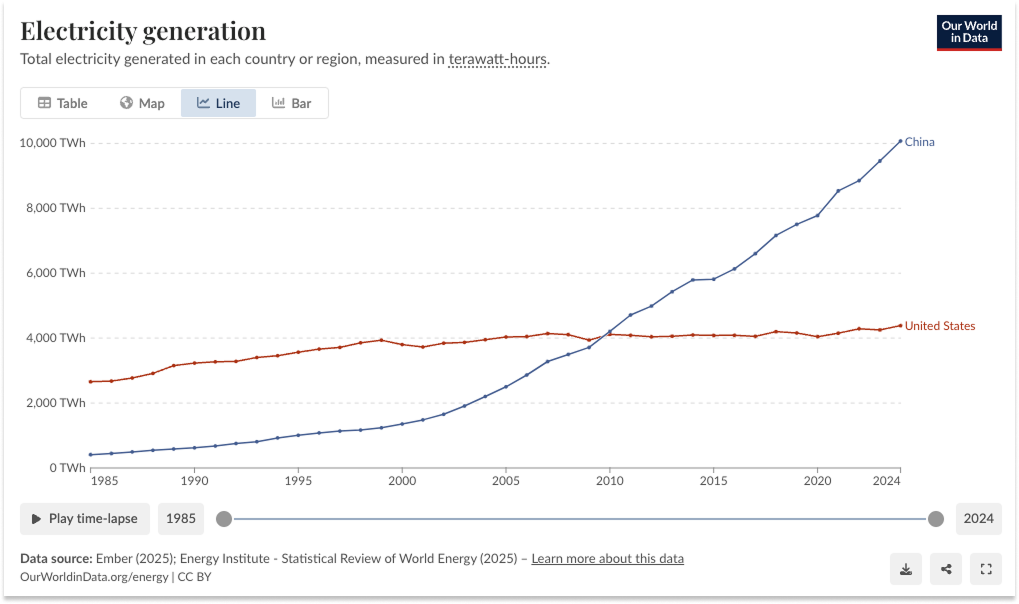

After catching up to America in electricity generation in just 2010, China now generates 2.5x as much electricity as we do.

It also dominates the technologies that turn electricity into action: the Electric Stack.

Lithium-Ion Batteries

Magnets and Electric Motors

Power Electronics

Embedded Compute

Today, China produces 75% of lithium-ion batteries globally and manufactures 90% of the neodymium magnets that make motors spin. In power electronics and embedded compute, it’s rapidly gaining ground.

That means that China controls the means of producing electric vehicles (EVs), drones, robots, and all of the other electric products that are replacing the combustion-driven machines on which America built its might.

As we speak, everything that moves, heats, lights up, computes, or converts energy is being rebuilt to perform better, faster, cheaper, quieter, and as a freebie, cleaner around electric technology.

Simply put: anything that can go electric will.

Or rather, anything that can go electric economically will.

Every year, the number of things that can economically go electric increases as their components get cheaper and more performant. Every year, China grows its Electric Stack capabilities relative to the West. Taken together, that means that more of the physical cutting edge will be Made in China.

And as humanity infuses machines with intelligence, more of those intelligent machines will be Chinese.

This is why China is happy commoditizing AI. They believe that action is the much harder, and therefore more valuable, piece of the future to own.

To understand why China is making this bet, and why they're probably right, you need to understand what the Electric Stack is, how incredibly cheap it's gotten, and who controls each layer.

The deeper you go, the more ridiculous it feels to believe that if we simply build the best models, we will win economic and military dominance, once you appreciate how all of this stuff works, how it all fits together. You need to feel, in your bones, that research, great ideas, without the manufacturing might to turn them into scaled products is no moat.

What follows is a surprisingly thrilling 40,000-word story of Western invention and Eastern manufacturing, of GM selling our future for $70 million, of conferences in Pittsburgh and assembly lines in Fukushima, of exactly how it is that drones fly, and of cost curves.

The details matter because the details make the curve, and the curves are destiny.

Everyone reading this is likely familiar with Moore’s Law. Many of you are likely familiar with scaling laws in AI, and Rich Sutton’s associated Bitter Lesson. Somehow, as if by magic, these digital curves become self-fulfilling, their audacity attracting talent and capital that make them come true.

These curves apply to the physical world, too.

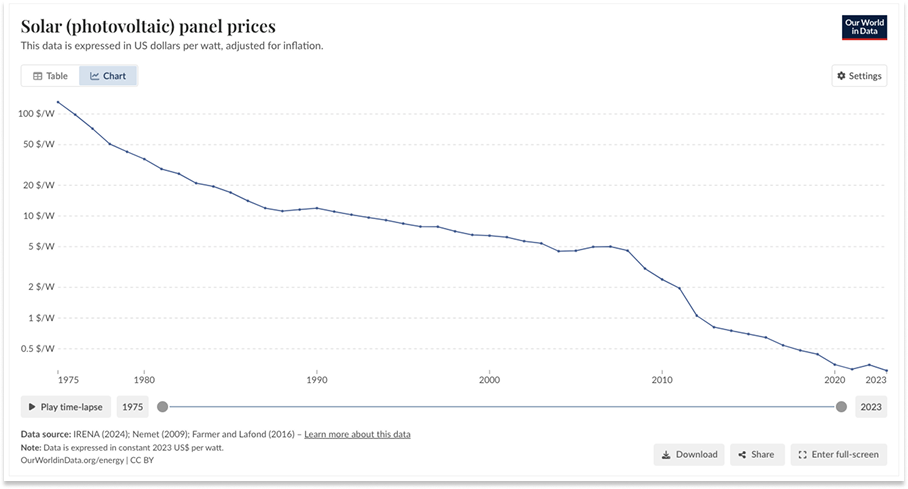

We are all familiar with the solar panel cost curves, which have seen solar power drop from $130.70 per watt in 1975 to $0.31 per watt today.

This has to do with electricity generation: turning some fuel – oil, coal, sunlight, wind, natural gas, uranium, or water - into electrons that can be used to power practically anything.

We are less familiar with another set of curves: those that make up the Electric Stack. These are the LEGO blocks that snap together to make the products that consume electricity and turn it into action.

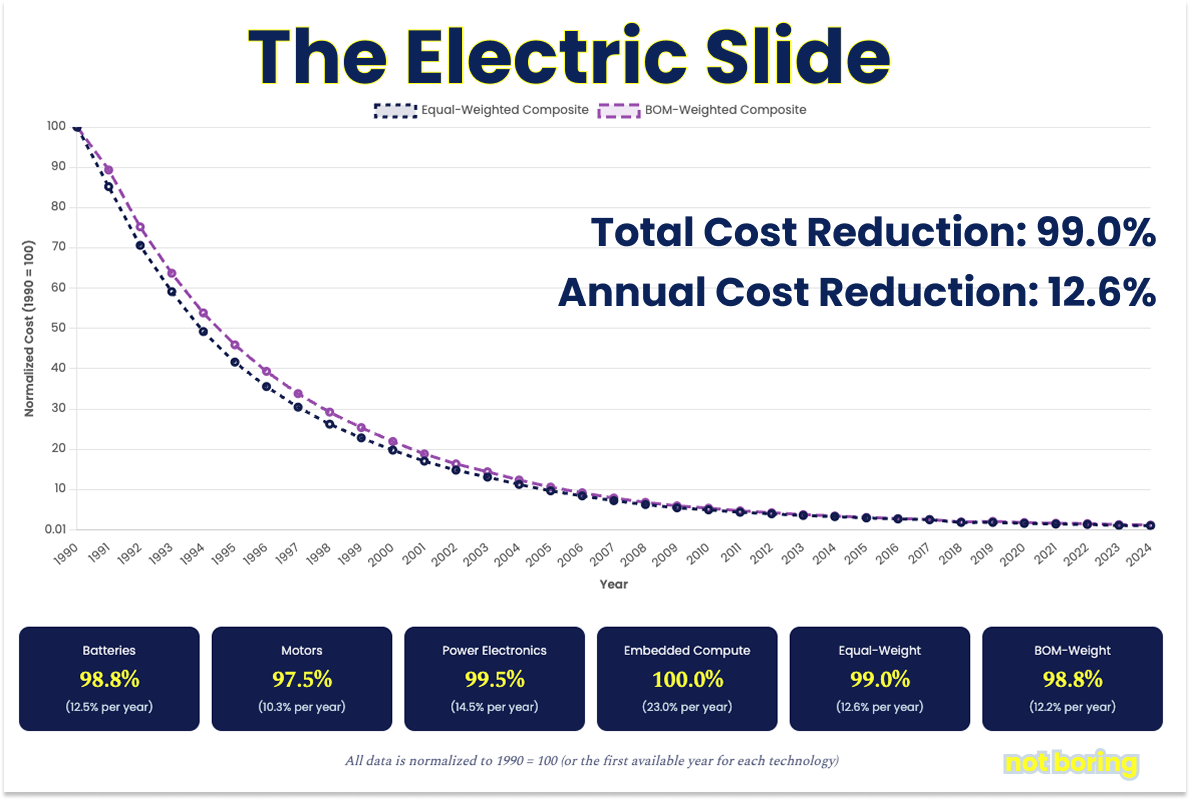

While there is a similar curve for batteries through 2018, there aren’t for the other layers of the Electric Stack, nor is there one Electric Stack curve. So we built them, in the hopes that they attract people to build on the Electric Stack like Moore’s Law has attracted people to build on computers.

Each curve tells a story.

Since Sony started rolling out lithium-ion batteries in 1991, battery packs have gotten 98.7% cheaper, for an annual decline of 12.5%.

Since hard-disk drive motors began incorporating Magnequench and Sumitomo neodymium magnets in late 1980s, the cost of electromagnetic actuation has dropped 98.8% from $204/kW to $5/kW, for an annual decline of 12.5%:1

Since industrial companies began using variable frequency drives (VFD) using B. Jayant Baliga’s insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBT) in the late 1980s, VFD inverters have gotten 99.5% cheaper, for an annual decline of 14.5%:

And since Texas Instruments commercialized microcontrollers (MCUs) and digital signal processors (DSPs) in calculators and kids toys in the late 1970s, the cost to run a million instructions per second (DMIPS) has fallen 99.9%, for an annual decline of 20% over the past 35 years:

To the best of our knowledge, no one has ever built a composite of these curves: equally weight each component of the Electric Stack to understand how much less it costs to build an electric product today than it did in the past.

We built it, and we call it: the Electric Slide.

It shows that the cost of the Electric Stack has fallen 99% since 1990, or 12.6% per year with an equal-weighted stack.

No product’s bill of materials (BOM) actually has equally weighted component costs, though, and no two BOMs are the same. A Tesla Model 3 might spend 60% of its BOM on batteries. A DJI Mavic 3 drone might devote 40% of its BOM to compute. So we cooked up an interactive Electric Slide that you can play with here:

That today China owns two layers of the Electric Stack almost entirely was not inevitable, or even likely.

The four key Electric Stack technologies were invented at various points between the 1960s and 1990s in America, Japan, and the UK, and reached critical maturity around the same time in the 1990s.

Then, in many cases, we sold the future. GM sold its neo magnets division, Magnequench, to China for $70 million. A123 Systems, which invented the Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) battery, went bankrupt and sold to Wanxiang for $257 million in 2013.

Thanks to shortsighted Western errors and farsighted Chinese industrial policy, in the commercialization phase, the Electric Stack center of gravity has moved from America and Japan to China, which dominates the stack. By controlling these four technologies, China has become the world leader in everything from EVs to drones to electric bikes to robots.

A giant piece of this is that mastery of this stack applies across domains, allowing market leaders like BYD to make everything from cars, to home energy products, to iPads, to much of the world’s drones. Within the whole sector – the components, software, and expertise largely transfer – meaning mastery of one product of the stack allows success in scaling others. Advantages compound. The result has been China getting the best “LEGO set” in the world, with regards to this stack.

Conrad Bastable calls this LEGO set the Electric Platform. For a sobering in-depth read on this topic, read his essay, Forsaking Industrialism. This essay owes Conrad an enormous debt for both that piece, and the conversation we had on Hyperlegible. I will reference both, explicitly or implicitly, throughout.

Put another way, over the past half-century, the technologies in the Electric Stack have gotten so cheap and so powerful that new entrants can build better-performing products than incumbents. This is true for companies - it’s a key enabler of my Vertical Integrators thesis - and it’s also true for countries.

As the Electric Stack technologies ride down their learning curves, China can better produce more of what the world wants.

Far from just making cheap components, its companies like BYD, DJI, and Huawei, have put themselves among the world’s most innovative integrators. In Q4 2024, BYD passed Tesla in sales. Per the IEA, “China continues to be the world’s EV manufacturing hub and is responsible for more than 70% of global production.”

Conversely, America is systematically overemphasizing the role AI will play in the future and underestimating the role that electrification will play.

As I wrote in Base Chapter 2: “While intelligence gets all of the attention, I’m increasingly convinced that what we’re entering is the Electric Era. Cars, robots, flying cars, drones, appliances, boats – anything that can go electric is going electric, because electric performs better. Even intelligence is reliant on access to electricity.”

More broadly, America’s implicit stance is: we will specialize in high-value creative work like software, chip design, and biotech research, while other countries, mainly Taiwan and China, handle the low-margin manufacturing. This is an outdated stance.

Manufacturing and design are inextricably linked. When you make things, you learn how to make them better. You learn which parts of the underlying stack need to be improved, improve them, and make better products. This is a theme that comes up over and over again in our Electric Stack story.

Texas Instruments won the Calculator Wars because it made its own microcontrollers. Sony took lithium-ion batteries from bench-scale to mass market scale and improved their efficiency by 50%. BYD made a lot of batteries, then it started making cars, and the deep knowledge of both allowed it to both bet on LFP early and develop the Blade Battery that it’s ridden to EV dominance. Not for nothing, DeepSeek was able to basically match OpenAI on less advanced chips because it went deeper into the guts of NVIDIA’s software than anyone else.

Ashlee Vance, who literally wrote the book on Elon Musk, recently wrote that, “The two biggest U.S. manufacturing success stories of the last twenty years are Tesla and SpaceX. And this is a problem.” It is not surprising that the person who sleeps on the factory floor and claims that the factory is the product, not to mention the entrepreneur who most heartily embraced vertical integration, is the one running both of those companies.

As we will see, the innovations that enabled the Model 3 came from a deep knowledge of all of the components that make up a Tesla, and how they work together. This same knowledge helped Tesla thrive through the COVID chip shortage.

Even worse, though, and if America’s advantage is in high-value creative work, AI capable enough to confer economic and military supremacy packages up and commoditizes that advantage.

As I pointed out in my conversation with Conrad, “If you believe that America's advantage is the IP and the design and all of that, the fact that we're racing to make that a commoditized good is actually super ironic in a way that I hadn't appreciated before.”

This, again, is why China is open sourcing intelligence.

Per Clayton Christensen’s Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits, if intelligence becomes commoditized, profits will move to adjacent layers of the value chain, like the electric product in which that intelligence lives. A robot with a commoditized brain may capture more of the profits in the value chain than the brains themselves, particularly if open source models get good enough.

To be blunt: in the Electric Era, maintaining design leadership without manufacturing leadership is not a coherent strategic position, and one that gets less coherent the better you believe AI will get.

And the Electric Era is coming, because electric products are simply better, and because they will keep getting better.

As part of my job, I get to see a little bit into the future, and from what I see, electric products will win the coming decades.

A few months ago, I went for a ride in Arc’s electric boat, the ArcSport, on Lake Austin. It was faster, sharper-turning, and quieter than any speedboat I’ve ever been on, and it docked itself.

A few weeks ago, I went to Zipline’s test site in California and watched, with my own eyes, as the drones held perfect position thanks to electric motors that can adjust thrust hundreds of times per second with perfect synchronization across multiple rotors, enabled by precise power electronics and real-time compute.

MRI machines, like those used to detect cancer early, depend entirely on powerful, precisely controlled electromagnets. Residential batteries, like Base Power Company’s, can’t back up homes or balance the grid without the Electric Stack. Robots, whether modern industrial robots, surgical robots, Matic’s floor-cleaning robot, or futuristic humanoids, are made up of servomotors, sophisticated power electronics, lithium batteries, and advanced compute.

These products all exist today. As the cost of Electric Stack continues to decline and performance continues to improve, new products enter the feasibility window.

Astro Mechanica can build efficient supersonic planes, for example, because electric motors have gotten powerful enough for their weight. Electric planes will begin to make sense as batteries get more dense and motors more efficient. So too will flying cars. And if we want affordable humanoid robots, even more than smarter intelligence, we need better batteries, motors, inverters, and microcontrollers.

In fact, if we want AI to play a role in any of our physical products, they need to be rebuilt on the Electric Stack first, so that they can speak AI’s language.

One of the reasons, I suspect, that America is so excited about AI and pays relatively little attention to electrification (which, somehow, has been politicized) is that the Electric Stack is messy. It exists in the real world.

It is easy to imagine that a magical digital technology we don’t quite understand but seem to be the best at will miraculously fix what ails us. It is harder to imagine how in the world we might rebuild, and improve upon, such an interconnected, physical stack of technologies, a stack that has taken decades of research, luck, market forces, genius, and elbow grease to get to this point, and one which China so thoroughly dominates.

The time for wishful thinking is over. There is a world to be rebuilt.

Whoever owns the Electric Stack owns the right to rebuild it in their image.

The learning curves are an incredibly useful guide: they tell us where we’ve been, and more importantly, where we’re going.

But the curves are too smooth for real understanding. That smoothness masks a ton of complexity: the research, the failures, the coincidences, the business deals, the products, the industrial planning, and the ingenuity that somehow, almost impossibly, came together to create the world we live in.

So we will need to cover both, and we will need to go incredibly deep, so you get a real feel for the thing, for the magnitude of both the miracle and the challenge.

If America wants to win the future – not because we’re itching for a fight, but because we want to maintain our role as the world’s largest and most innovative economy – we will need to vertically integrate. We need to have the ability to manufacture every part of the Electric Stack, the understanding of how to build the best products that comes from that ability, and the ability to scale.

Getting this mojo back won’t be easy. It seems almost impossible. It will take industrial policy, innovation, government support, consumer demand, and a little free market magic to pull it off. Currently, we are shooting ourselves in the steel-toed foot.

One thing we’ll learn in studying the history is that demand for electric products drives scale, cost declines, and performance improvements.

Unfortunately, electrification has become unnecessarily politicized in America, with cultural associations obscuring the hard strategic realities. While the current administration has shown understanding of electricity generation through nuclear EOs and of component importance through investments like the Pentagon’s $400 million in MP Materials, the rollback of demand-side incentives undermines the very learning curves that could restore American manufacturing dominance.

If I were President, I would make sure that every American man, woman, and child has an EV, heat pump, drone, induction stove, and robot. American demand is perhaps the most powerful motor in the world, and our best shot at economically onshoring enough of the Electric Stack to remain competitive in the Electric Era.

My hope is that by better understanding how we got here, we can avoid mistakes like this and better determine where to go next.

The Roadmap

This is not a short essay, nor a light one, even by Not Boring’s standards. There are a few reasons for that.

First and foremost, given what I believe to be the importance of the Electric Stack to the modern world and its future, we are woefully unfamiliar with its history and details.

When I say “we,” I certainly mean me. As you might be able to tell, the process of writing this essay involved a lot of “OH! That’s how that works.” Just as we hand-wave that AI will fix everything, we handwave about the components of the Electric Stack based on a headline we read in the WSJ or a tweet we scrolled by in our feed.

“It's critical that America not rely on China for batteries!” Yes, but why, and at which level should we integrate? “China controls 90% of rare earth magnet production!” Yes, OK, but what is a rare earth magnet, what does it do, why is it important that we manufacture them here, and how might we be able to do that? I hope that by diving into an insane level of historical detail, we can have more nuanced conversations about the future.

Second, because I find this stuff fascinating. The tale is full of hidden legends and business case studies - triumphs and fumbles - that shape how the world moves.

Any hope of getting our efforts right this time requires an understanding of where they’ve gone wrong (or right) in the past.

Finally, because the curves themselves tell stories, predict the future, and in so doing, bring that future into existence.

The components that make up modern electric products have gotten so cheap and so performant that entirely new things are becoming possible and economical each year. And while they feel less likely to continue because they have to interact with the physical world, somehow, they do. People keep underestimating how cheap solar is going to be; the same should be true for most things built on the Electric Stack.

That’s another reason to write the stories in addition to simply showing the curves. Every story shows a technological tree that seems to have hit its last branch, before someone, somewhere tries a new chemistry, adds a new element, or configures the LEGO blocks in just such a way that, suddenly, it just kind of works, works enough, at least, for a specific product that really needs it to work just that way… and the rest is history. The curves continue.

There’s a risk in an essay like this of painting one of two pictures: either that we must do everything in our power to beat China or that we are so hopelessly behind that there’s no point, that we should just focus on the game we can win, even if it’s not the most important game.

I think the curves tell an optimistic story: that, thanks in large part to Western science and Eastern manufacturing, these technologies have now reached a point at which it is becoming increasingly possible to build an Electric world, economically.

This is a long piece, but it’s one that I’ve loved researching and writing over the past month, and I think it’s the most comprehensive resource for those who want to understand how we got here and where we might go in the Electric Era.

We will cover:

A Brief History of Electromagnetism: The force driving the Electric Era.

How Electric Motors Work: Establishing the fundamentals.

Lithium-Ion Batteries: Li-Ion, NMC, NCA, Tesla, BYD, CATL, and LFP.

Magnets and Electric Motors: the neodymium magnets that spin the world.

The Century of Semiconductors: the birth of compute.

Power Electronics and Control Systems: controlling electricity with itself.

Embedded Compute: microcontrollers, DSPs, ARM, and RISC-V.

Lessons and Takeaways: What can we learn from the history of the Electric Stack?

Rebuilding the Electric Stack: What it will take to build the future.

To be clear upfront: rebuilding the Electric Stack in the West will be hard, but possible. America still owns the greatest demand and entrepreneurial engines the world has ever seen. We will need to run both at about a million RPMs.

So without further ado, let’s begin. And we must begin, of course, all the way at the bottom, with some fundamental physics.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Not Boring by Packy McCormick to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.