Welcome to the ??? newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday - on Thursday, Substack suddenly cut my subscriber count by ~1,200 and I’m not sure why. But onwards: join 46,123 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotifyor Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is presented by… Masterworks

In January I wrote about Masterworks. As a refresher, Masterworks is the first and only platform that lets regular folks (like me) invest in blue-chip artworks at a fraction of the entry price. At the time I had invested in three Masterworks offerings. Since then I have added three more pieces to my portfolio: a Haring, a Bradford, and another Basquiat. Fancy.

Not only do I think it’s prudent to have real asset exposure to hedge against inflation (thanks J Pow 😉 ), but I also love learning about these artists and their markets, and Masterworks brings some intense data analysis to the table.

Art can make sense in everyone’s portfolio. Contemporary art returned 13.6% from 1995-2020 with a low loss rate and virtually no correlation to equities. Plus, unlike other collectables or even BTC, supply is constantly decreasing. It’s kind of like ETH … ultrasound art 🦇🔊

I teamed up with Masterworks to let you skip their 11,500 person waitlist. Try it.*

*See important info

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

Mario Gabriele is one of my favorite writers. Read the opening paragraphs in this essay and you’ll understand why. He somehow makes business writing beautiful.

Between his briefings, Startup Ideas, and The S-1 Club, Mario’s The Generalist is can’t miss content. If you like Not Boring, you’ll like The Generalist.

Aside from a general business nerdiness, Mario and I share a few things in common:

A fascination with conglomerates.

Large Indian readerships.

This week, with India’s COVID crisis continuing to escalate to frightening heights, we decided to team up to explore the past, present, and future of one of India’s most beloved companies, and one of the leaders in the fight against COVID: Tata Group.

In addition to bringing awareness, Mario and I have both made donations to organizations aiding India's fight against the coronavirus. We'd encourage those of you that can to do the same. Both New York Magazine and the New York Times have lists of reputable NGOs putting funds to good use. If you’re in India, my friends at Pesto put together a website with resources including ICU beds and oxygen supplies.

Let’s get to it.

Transforming Tata

A message to all the tycoons out there: beware of your grandchild.

Though the Bible advances the parable of the prodigal son — the wasteful offspring that fritters a father’s money — statistically, it is the third generation that marks the end of a family fortune. One American study indicated that 90% of wealth evaporates by that point, the casualty of frivolous investments, generational dilution, and dwindling determination. Even the colossal wealth of Cornelius Vanderbilt — worth $227 billion when adjusted for inflation, giving him a cool $96 billion edge over Bezos — dissolved in his expanding gene pool.

All of which is to say: that Tata is here at all is remarkable.

Four generations and more than 150 years after its founding, Tata is not only still standing but essential. Just this week, the company aided in India’s coronavirus response, agreeing to contribute 800 tonnes of oxygen per day to health facilities in need. Far from an isolated example, such civic-mindedness is at the heart of Tata’s history, no doubt part of the reason one Twitter commentator referred to it as India’s “parallel government.” Over a century and a half, the conglomerate has supported (and commercialized) Indian life, unlike any other company. In the process, Tata has constructed a dizzying tessellate of over 100 businesses, from automobiles to apparel, steel production to tea.

And yet, there’s the sense that despite its durability, Tata’s may be in decline. With infighting beleaguering the founding families and legacy businesses struggling to adapt to a digital world, Tata will need to work hard to ensure it remains a potent force. To do so, the company will need to shed legacy baggage, embrace the opportunities the tech sector presents, and lean into the essence of what makes Tata an enduring brand.

In today’s piece, we’ll explore:

Tata’s rich history, beginning with the opium trade

The complexion of a messy conglomerate

The necessary moves to perpetuate the dynasty

History

The story of Tata Group is the story of modern India. The conglomerate’s creation and ascent both influenced and responded to seismic changes in the country beginning under colonialist rule, adapting under socialist independence, and flourishing in an open economy.

It all begins in 1822 in a city on India’s Western Coast.

Nusserwanji: Zoroastrianism and family business

Every company is defined by its culture. On that count, Tata can lay claim to an especially ancient heritage: the religion of Zoroastrianism.

Founded in the 6th century BC, Zoroastrianism is defined by a stark delineation between good and evil, and a gentler gospel of kindness. As noted in the excellent The Tata Group book, adherents believe to attain happiness you must help others, and that salvation is achieved by “Humata, Hukhta, Hvarshta” or “good thoughts, good words, good deeds.” Hundreds of years later, those three words were inscribed on the mausoleum of Tata’s Chairman, emphasizing how Tata’s civic and philanthropic orientation is inextricably linked with the religion.

Nusserwanji Tata must have been something of a rebel. Born in 1822 in India’s Gujarat region, Nusserwanji was the first family member in over fifteen generations to eschew the call of Zoroastrian priesthood and enter the private sector. He learned the ropes by training with a Hindu banker before setting out on his own, founding an export firm with a focus on opium, and other less scandalous commodities.

As the firm grew, Nusserwanji began to rely more on his son, Jamsetji, bringing him into the fold in 1859. Educated at the English-influenced Elphinstone College, Jamsetji had the privilege of a more global worldview than his father, fostered by business trips to London and Manchester. The latter city, seething with industrial energy, was believed to have made a particularly strong impact, with the young Jamsetji simultaneously enraptured by Manchester’s industry and disgusted by the “medieval vision of hell” in which workers toiled.

But amidst the smoke and chaos, he saw promise. It was time to build a “Manchester in the East” with a humanity that would put India’s colonists to shame.

Jamsetji: Founding Tata Group

In 1868, Jamsetji officially founded Tata Group, beginning with an investment of 21,000 rupees. Over the succeeding 36 years, he would establish a generational business and set in motion a series of ambitious infrastructure plans, earning the nickname of “the man who saw tomorrow.” That growth would be achieved while treating workers with uncommon dignity and respect.

It started with the acquisition of a decrepit oil mill. Jamsetji promptly transformed it into a cotton production facility before selling for a quick profit. (Let’s get that IRR, Jamsetji.) Aided by a fact-finding trip to Lancashire and the recruitment of English specialists, Jamsetji parlayed that win into the creation of Empress Mills — a new cotton facility that drew on global knowledge. Two additional mills followed.

Those four cotton mills set the financial groundwork for Tata’s later expansion, as well as pioneering the company’s legendary culture and care for its employees. Among other innovations, Jamsetji took pains to ensure workers had access to filtered water, sanitary facilities, low-cost grain, credit, a library, a pension fund, accident compensation, and much more. All of this at a time when the notion of managerial benevolence was effectively non-existent among Western industrialists. Decades later Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle would show American manufacturing was a theatre of callous peril.

Jamsetji was savvy enough to realize that these investments also paid off, aiding recruitment and drastically lowering attrition. It was not uncommon for absenteeism to reach 20% in textile production; Tata’s was essentially 0%.

As Jamsetji’s wealth grew, his sights widened.

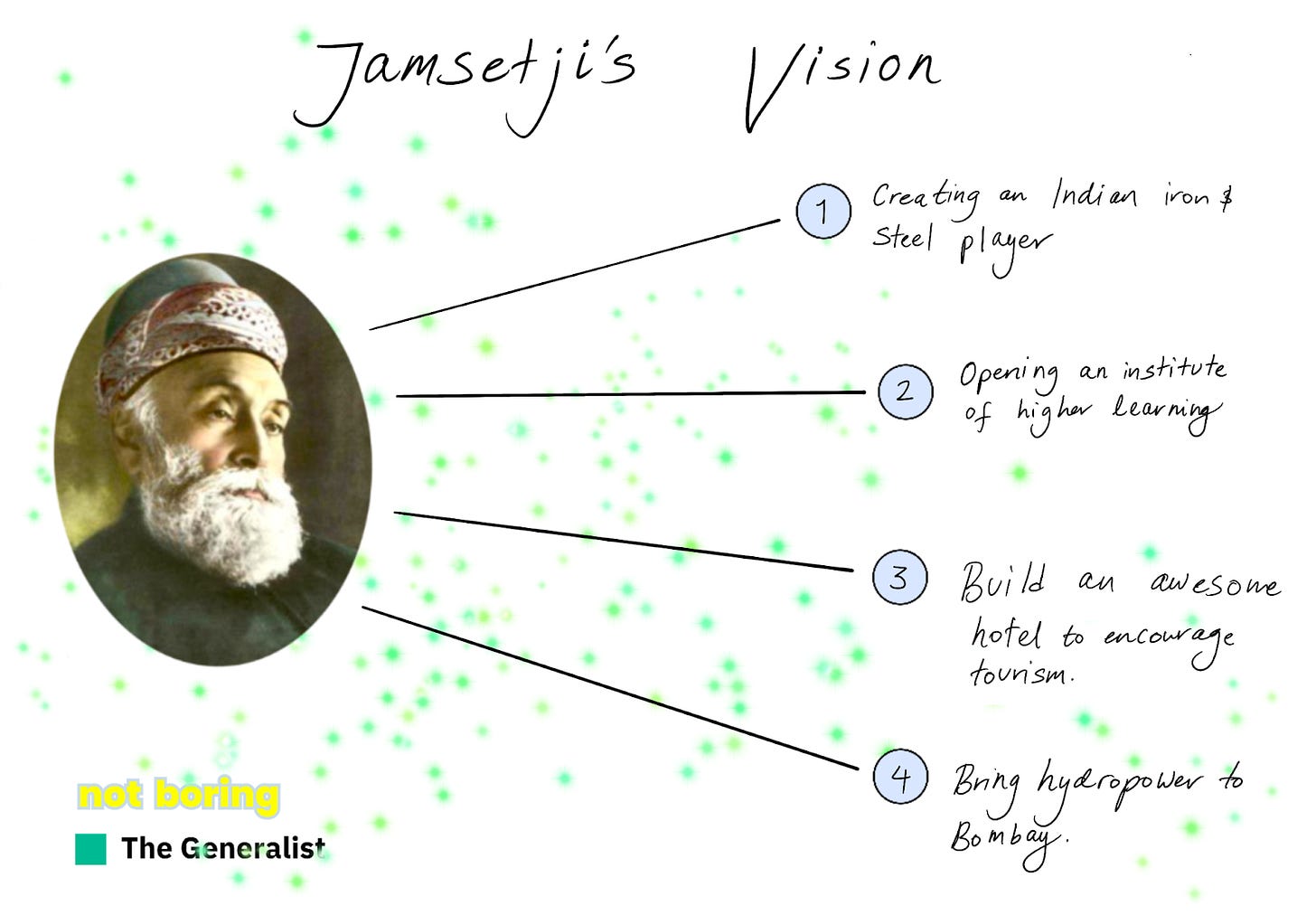

With travel to both Europe and Japan sharpening his worldview, he became increasingly nationalistic. The second half of his career focused on four critical initiatives designed to elevate his homeland:

Patriating the manufacturing of iron and steel

Empowering science and technological education in India

Growing the national tourism industry through the construction of hotels

Bringing low-cost, safe electrical power to his beloved city of Bombay

Jamsetji saw the first two of these as essential if India was to gain independence, noting:

Freedom without the strength to support it and, if need be, defend it, would be a cruel delusion. And the strength to defend freedom can itself only come from widespread industrialization and the infusion of modern science and technology into the country’s economic life.

Of these four goals, Jamsetji would live to see only one brought to full fruition. In 1903, he opened the iconic Taj Hotel in Bombay. Not only did it feature air conditioning, a rarity at that time, but it was the first building in the city to boast electric lighting.

Jamsetji would make serious strides with regard to his other goals, but he would need his son Dorabji to turn them into a reality. In 1904, at the age of 65, Jamsetji passed away. Among his last words were these, directed to a family member:

Do not let things slide. Go on doing my work and increasing it, but if you cannot, do not lose what we have already done.

Dorabji: Manifesting the vision

A keen sportsman in his youth who began his career as a journalist, Dorabji stepped into his father’s shoes after his death and in a blockbuster three-year span brought Jamsetji’s dreams to fruition, launching a hydroelectric power division, a best-in-class technological university, and a steel business.

In 1910, more than three decades after his father had been bewitched by a visit to Niagara Falls, Dorabji launched the Tata Hydroelectric Company, bringing clean energy to Bombay. It represented a titanic achievement that was, once again, aided by knowhow from overseas. From The Tata Group:

An army of 7,000 workers installed pipelines from Germany, waterwheels from Switzerland, generators from America and cables from England on the steepest slopes and roughest terrains of Lonavala and Khandala.

Showing frankly ludicrous foresight, Dorabji recognized (as his father had) the dangerous climatic potential of Bombay’s smoke-spewing coal-powered textile mills, taking the time to educate local owners and offering to buy back the steam engines they used to help make a transition to sustainable power.

Dorabji followed up that success with the 1911 opening of The Indian Institute of Science (IISc). Bringing the project to fruition required significant political savvy with first Jamsetji and then Dorabji lobbying the office of the British Raj over the years. Since its inception, IISc has become one of India’s finest institutes of higher learning, training a steady stream of scientists and technologists.

The final piece of Jamsetji’s dream arrived in 1912 and in many ways, it has proven to be the most enduring: The Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO). That Dorabji succeeded at all was proof of a political shift in India.

Rebutted by British investors, Tata sought to finance the project in India, floating shares in 1907. With the Swadeshi movement — the push for self-rule — growing, Tata’s offering was met with huge interest. Investors hounded management and even showed up at the company’s headquarters to try and make their case. Within a matter of weeks, the requisite capital was secured — the largest raise of its kind in India, in the industrial sector.

Beyond executing Jamsetji’s wishes, Dorabji also added to the Tata empire, starting a cement manufacturing division, a construction business, a life insurance line, as well as making forays into consumer staples like sugar and toiletries.

Not all of these extensions would last; with World War I artificially inflating the demand for many of Tata’s industrial products. The company’s financial state reached such tenuous levels that Dorabji had to put up his personal capital (and his wife’s jewelry) to secure the loan that would save TISCO from dissolution. That maneuver — a show of impressive dedication and a willingness to take risks — has been referred to as “the finest hour of Dorabji’s leadership.”

JRD: Expansion and decentralization

Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy, better known as JRD, was a cosmopolitan man. Born in Paris to a French mother and Indian father, he was educated in the French capital, London, Tokyo, and Bombay. Fittingly, he boasted the elegance and good looks of a matinee idol, sporting a refined moustache for much of his life.

As his name suggests, JRD was a member of the Tata family, but he wasn’t a direct descendant of Jamsetji. Rather he was a cousin-once-removed, chosen to step into a leadership position because of the relative dearth of available grandchildren (Dorabji had no children, his brother adopted one), his notable intellect, and a strength of character that brought to mind Jamsetji himself. Throughout his life, JRD would prove to be someone that played by the rules when it mattered — he was famous for ensuring Tata employees never took bribes — but was willing to push the boundaries.

In 1938, after an interregnum in which a cousin presided over the business, JRD ascended to Tata Group’s hot seat. When he arrived, the conglomerate managed 14 businesses; by the time he left, there would be 95.

Critical additions included:

1939, Tata Chemicals.

1945, Tata Engineering and Locomotive Company (TELCO).

1948, Air India.

1949, National Radio and Engineering Company (NELCO).

1952, Lakmé, a cosmetics business.

1954, Voltas, an air conditioning business.

1960, Tata Exports.

1963, Tata Tea, grown through the acquisition of Finlay tea.

1968, Tata Consulting Services (TCS), the basis for the now-dominant tech practice.

These were just the tip of the iceberg, of course. Dozens of others — from palm oil to precision machinery — peppered JRD’s period of innovation.

Just as impressively, this growth was managed during a period of extreme political instability and change as India regained its independence and responded to the demands of different political parties.

For example, under Nehru, both Air India and Tata’s life insurance business were nationalized. Losing control of the former was a particular tragedy for JRD who had a love for aviation that traced back to his father’s friendship with Louis Blériot, the first man to fly across the English channel. JRD was actually the first person to receive a pilot’s license in India. (JRD also loved fast cars; he met his wife when got caught for racing his Bugatti down a Bombay boulevard and needed a lawyer. The lawyer’s daughter became his betrothed.)

But Nehru giveth as well as taketh away.

After banning non-essential imports, the Indian government found itself pressured by a surprising group: “the elite women of Delhi.” Without a native cosmetics supplier, women were left without make-up; to amend the problem, Nehru asked Tata to enter the space, leading to the creation of Lakmé.

Indira Gandhi’s tenure required yet another adjustment with legislation forcing each of Tata’s subsidiaries to operate independently, governed by a board of directors. Though there were plenty of nuances to the change, the upshot was profound: the parent company couldn’t directly control its component pieces.

Thankfully, JRD didn’t need to rule by force. His natural magnetism and the steps he had already taken to push more responsibility down to individual companies, advancing a decentralized approach, was repaid. Even with Gandhi’s new rules, the conglomerate’s strategy was still defined at the top, with individual chiefs happy to follow JRD’s lead.

At the age of 87, JRD finally stepped down from his role as Chairman. He had turned Tata from a strong national player into the country’s defining enterprise. He turned to a younger face to take the company forward.

Ratan: Collaboration and control

Like JRD, Ratan Tata had spent some of his formative years abroad, completing high school at Riverdale Country in New York. After graduating, he completed a degree in architecture from Cornell — a qualification that some suggested encapsulated Ratan’s well-roundedness: he was methodical, certainly, but creative, too.

After illustrating his business acumen in turning around NELCO, Tata’s radio division, Ratan was tapped by JRD to take his place. In 1991, he officially became Tata’s chairman, a position he held until 2012 (and again as interim chair between 2016 and 2017). Tata’s current incarnation owes much to his vision.

During his tenure, Ratan focused on two critical initiatives: more tightly controlling the conglomerate, and positioning Tata as a global collaborator and dealmaker.

What looks like a masterful move in one context can look limiting in another. If JRD showed dexterity in pursuing a decentralized approach under socialist rule, his successor was just as wise to reverse the strategy in later years. Operating in an open, global economic market, Ratan concluded that Tata Group needed to own a greater share in its constituent companies and foster closer collaboration. Between 1992 and 2002, Ratan meaningfully increased the parent company’s stake in key units, growing its holding in Tata Steel from 8% to 26% and expanding a 17% position in Tata Motors to 32%. At the same time, Ratan instituted stronger central governance, codifying core values, and setting up both a policy board and quality management group. This final initiative ensured best practices were distributed between different units, in addition to facilitating meetings between leaders. As noted in The Tata Group:

Meetings across group companies marked the change in the Tata Group culture from independent identities to a unified Tata family.

While Ratan clearly saw an open market as something of a threat, he was quick to recognize it as an opportunity, too. While Ratan sunsetted or sold under-performing business lines (including Lakmé) he also expanded Tata’s purview through partnerships.

Just as Tencent now serves as the ferryman to China (think Roblox with Luobulesi), Tata has often played the same role with India, collaborating with Daimler to manufacture Mercedes-Benz in the country, delivering insurance alongside behemoth AIG, and partnering with Starbucks to offer coffee from Kargil to Kochi. (You: Did they just look up the northernmost and southernmost Indian towns with a hard “C” sound? Us, intellectuals: Tumhari himmat kaise hui?)

Ratan also bolstered Tata’s existing positions through M&A. Among his key purchases:

2000, Tetley Group for $450 million

2004, a unit of Daewoo for $102 million

2005, NatSteel, Singapore’s largest steel provider, for $365 million

2006, the Ritz-Carlton in Boston for $170 million

2007, Cronus, a steelmaker, for $11.3 billion

2008, Jaguar and Land Rover for $2.3 billion

2008, General Chemical Industrial Products for $1 billion

Still, a key figure, Ratan’s reign served to consolidate Tata’s operations and modernize it. Immediately followed by Cyrus Mistry (more below), Ratan found a truer success in Natarajan Chandrasekaran (“Chandra”). For an empire so steeped in the tenets of Zoroastrianism, it was a significant appointment: Chandra was the first non-Parsi executive to take the helm.

Tata Today

“You would not probably look at the Tata Group as a modern conglomerate. The most important [thing] is to define themselves.”

-- Anonymous source close to Tata Group, Financial Times, April 2021

Today, despite its first outside Chairman, Tata’s corporate structure reflects its history.

Ordered chaos. Juxtaposition of rich and poor. Proud legacy transitioning to tech-led future. Layers of new structures built on top of old.

It looks more like India itself than like other conglomerates.

Most of the world’s largest conglomerates are structured in a couple of ways:

Publicly traded parent company with wholly-owned subsidiaries or investments. (Tencent, Reliance, Alibaba, Berkshire Hathaway, Constellation)

Private all the way down. (Koch)

Tata is built different.

First, the parent company, Tata Sons, is a Private Limited Company. It has just 28 shareholders, who fall into four buckets: Tata Trusts, Mistry Family (via Shapoorji Pallonji Group), Individuals (mainly Tata family members), and Subsidiaries.

Tata is unique among multi-hundred billion dollar companies in that it is majority owned by charitable trusts. Corporate social responsibility is a buzzphrase for most companies; for Tata, it’s structural. That structure has allowed the company to support India through COVID, with more than token gestures. While we noted that this week saw Tata step up its oxygen contributions, the firm has also donated $200 million to relief efforts, spent heavily on bringing supplies to India, and helped improve rapid testing capabilities.

The Tatas and their trusts are in the process of consolidating their ownership even further. After a falling out related to Ratan Tata’s removal of Cyrus Mistry as Tata Group Chairman in 2016, and a March Indian Supreme Court ruling against Mistry’s claim that the ouster was illegal, the two families are negotiating the Tatas’ purchase of the Mistrys’ 18.4% stake.

As Tata Sons cleans up its ownership, it’s cleaning up the entities it controls as well. In 2019, under now-Chairman Natarajan Chandra, Tata reorganized its 30 listed companies and their roughly 1,000 subsidiaries into ten verticals.

The reorganization was part of Chandra’s process of simplifying, synergizing, and scaling (3S). Starting under Ratan and continuing under Chandra, Tata Sons is working to take advantage of its combined resources and expertise. That’s no small task given the ownership structure and the fact that each company has its own Board of Directors.

It requires a light touch, sharing best practices instead of dictating. Ravi Arora, Tata’s VP of Innovation, described that loose influence on the Stretch Thinking podcast:

Every company in the TATA Group impacts others in the group because we are one family, although every company is independent. But we do influence each other, and we also learn from each other.

That’s hardly the top-down decision-making you’d expect from a company like Reliance, but it seems to be working. Tata’s seventeen public holdings combined are now worth more than Reliance, making Tata India’s largest conglomerate.

To be sure, Reliance Industries, helmed by Mukesh Ambani, is still cleaner. Invest in Reliance, get everything that it owns. The company is complex -- it has 158 subsidiaries and seven associate entities across six business lines -- but it’s all wrapped up in one publicly traded stock. It’s the most valuable publicly traded Indian conglomerate with a market cap of $176 billion. And it’s more nimble, a point we’ll return to shortly.

Tata, on the other hand, isn’t publicly traded. Instead, it owns stakes in thirty-one companies, 17 of which are publicly traded, across ten verticals. Many of the subsidiaries use the Tata name, which the parent company licenses to them under Brand Equity and Business Promotion agreements. The Tata brand alone is the most valuable in India, with an estimated value of $20 billion. Each company operates independently under its own board of directors.

As of March 31, 2020, in the early throes of the pandemic, Tata said the combined market cap of its companies was $123 billion. Today, the combined market cap of its 17 publicly traded subsidiaries has nearly doubled to $234 billion, $58 billion higher than Reliance’s market cap.

(For a live tracker of all 17 companies’ market caps, check out: Tata Subsidiaries Market Cap)

That said, because of the company’s long history, through good economic times and bad, the Group only holds partial stakes in most of its companies. In some cases, that’s because it sold off stakes to raise cash. In others, as with Titan, of which it only owns 25%, that’s because it decided to let its executives start the business on the condition that they could raise the capital themselves. This chart gives an outdated but directionally-correct overview of Tata Sons’ ownership.

That presents challenges, chief among them that it’s much harder for Tata to force its affiliated companies to do anything. Instead, it needs to provide guidance, share best practices, and try to use its heft as the largest shareholder to shape outcomes.

It also means that while Tata Sons doesn’t get all of the upside from their companies, its name allows them to lever up, creating a heavy debt load on its businesses.

It’s all a bit of a mess. But there’s a bright spot: Tata Consultancy Services (TCS).

Tata Consultancy Services

A key indicator of the company’s importance is the fact that Chandra, the first Tata Chairman not born into the Tata or Mistry families, served as TCS’ CEO before ascending to the top spot.

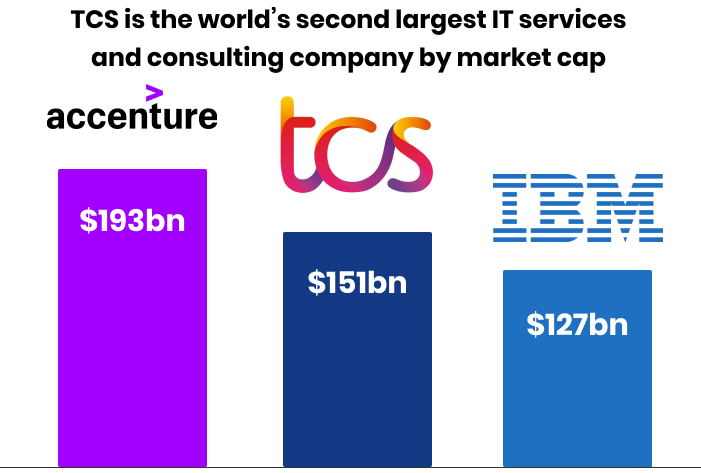

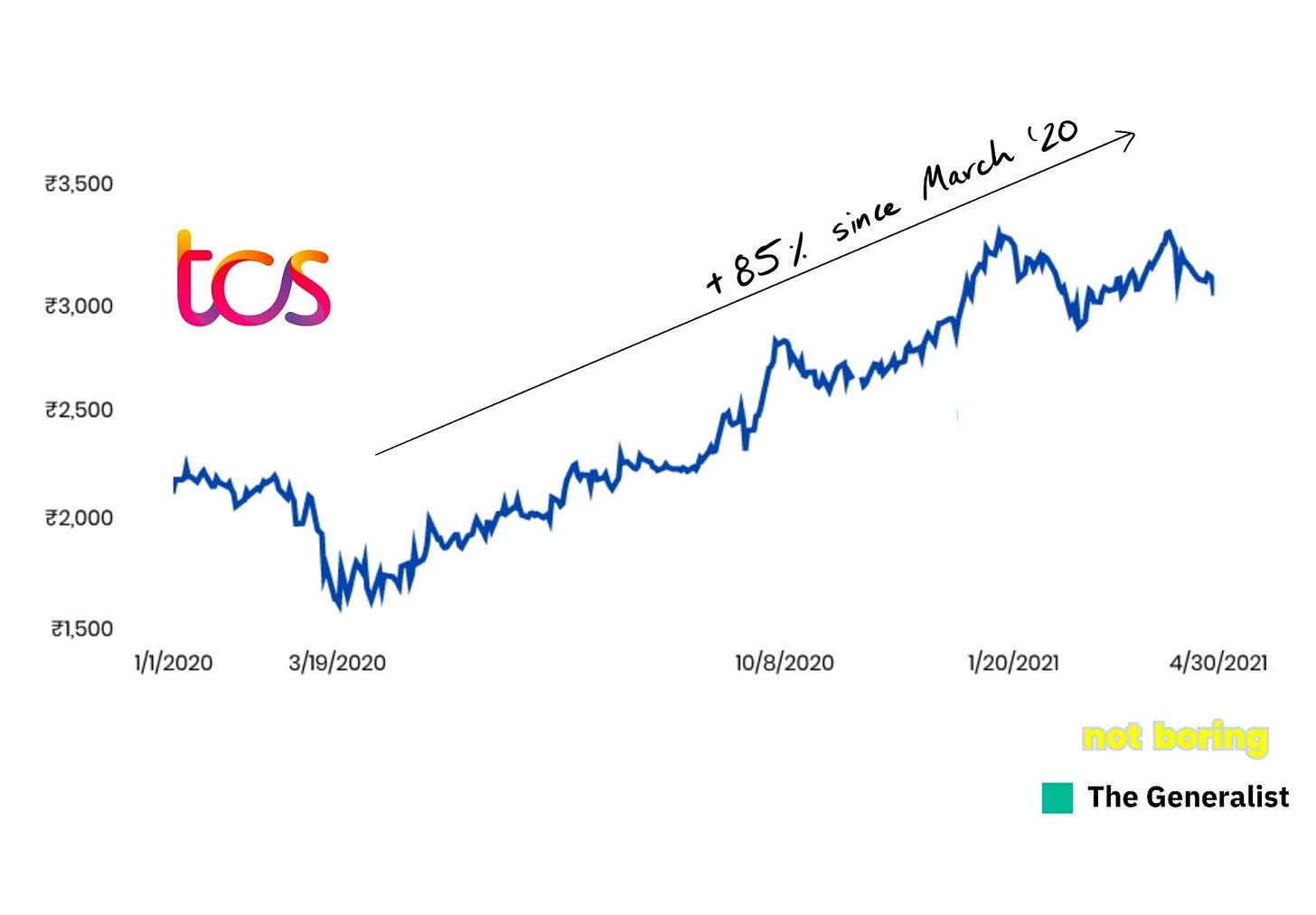

TCS is a monster. It employs 488,000 people, counts Microsoft, GE, SAP, and Thomson Reuters among its global clients, and offers the full range of IT services, consulting, and digital transformation, from cloud to AI to cybersecurity and even blockchain. It is the largest IT services and consulting company in India, and does battle with Accenture and IBM for the crown of world #1.

TCS benefited from companies around the globe’s COVID-fueled race to digitize. TCS is worth 40% more than it was at the beginning of 2020, and is up 85% from March 2020 lows.

Now, TCS is worth twice as much in the public markets as all of Tata’s other companies combined, and worth nearly as much as all of Reliance Industries on its own. Just as the football team at a large state school funds all of the athletic programs, TCS funds Tata Sons. In 2019-2020, the company spit off ₹73 per share in dividends, of which Tata Sons, as 72.19% owner, received $3.1 billion at today’s exchange rates. TCS regularly generates over 70% of all dividends paid to the parent company.

That makes sense. In a recent article, FT pointed out that while Tata Motors is Tata Group’s biggest revenue driver (pun intended), TCS generates most of its profits.

Those charts highlight TCS’ relative importance, but they’re also a flashing neon sign pointing to Tata’s biggest challenge today: Tata is carrying a lot of dead weight.

Tata’s Dead Weight

Tata Consultancy Services contributes 70-90% of Tata Sons’ revenue in the form of dividends. It’s one of very few Tata Group companies, along with Titan, Tata’s watches, jewelry, and accessories maker, that has actually grown profits over the past few years. Many of Tata’s other companies are dead weight. According to BusinessToday and annual report analysis:

Tata Steel generated $2 billion in 2019-2020 profits, but has net debts of $11.6 billion and is dragged down by the performance of its European units, which it has been trying to sell. It will need to refocus on the Indian market, where it is hugely profitable because of captive iron ore mines.

Tata Power saw its profits cut in half from $351 million in 2019 to $177 million in 2020, and has net debts of $4.9 billion. It did decrease its net debt to EBITDA ratio from 6.2x to 5.2x between 2019 and 2020, but will need to further pay down debt and transition to renewables in the coming years.

Tata Motors, including Jaguar Land Rover, brought in a whopping $35 billion in FY2020 revenue, but generated negative $1.2 billion of free cash flow. It also carries $7.4 billion in net debt. While motors is one of Tata’s sexiest and most well-known businesses, it has a ton of work to do to transition its lineup to electric, and is paring down its offerings to focus on Indian passenger cars, commercial vehicles, and Jaguar Land Rover. At home, it’s under pressure from an increase in foreign car sales.

These are just a few examples across Tata’s sprawling portfolio. Over the years, the Group leveraged its brand trust to acquire or launch new products and raise debt to fuel expansion. Some, like Jaguar Land Rover, were the result of overeager and misguided acquisitions. Many were the result of a strategy that once made sense but no longer does. For a while, particularly before imports came to India in a meaningful way, it worked. Packy’s father-in-law told him that Tata introduced many products to the Indian market for the first time. When you have consumer trust, and consumers have no other options, going wide makes sense. You can sell them anything.

But today, faced with best-in-class products from across the world, many of Tata’s companies are overextended and uncompetitive. Ratan’s early aughts buying spree only exacerbated the problem.

When he took over as Chairman in 2017, Chandra’s goal was to right a lot of his predecessor’s mistakes. He used a corporate-friendly tagline: “simplification and synergies.” He’s working to bring order to the chaos, and focus the Tata companies on the right things:

Combined Tata Chemicals and Tata Global Beverages into Tata Consumer Products.

Reorganized Tata Steel into four separate businesses and has transitioned production from majority-European to majority-Indian as it looks to sell off European units.

Moving Tata Powers’ renewable power assets, and their debt, into an infrastructure investment trust (InvIT) and is selling a stake to private equity to pay down debt. Tata Power is also looking to sell African and Indonesian assets.

Considered selling stakes in some of the company’s financial services units.

Disposed of some of Tata’s more random assets, like a chain of car dealerships.

It’s a start, but if Tata wants to win the future, it needs to go further. Even after simplifying and synergizing, Tata still follows an extreme version of the Pareto principle, with more than 80% of its profits coming from less than 20% of its efforts. TCS is still the Group’s engine, and most of the other companies are too sprawling, disconnected, minimally (or un-) profitable, debt-heavy, and backward-looking to help Tata build a modern conglomerate that wins the next century and brings India along with it.

What is a Modern Conglomerate?

When you think of the word “conglomerate,” you probably think of something that looks a lot like Tata does. Inspired by In Search of Excellence, many companies that generated a lot of cash by focusing on one thing and doing it really well decided to diversify. Good at selling concrete? Buy a chain of pizza restaurants. Made your money in telecoms? Get into defense contracting.

That method of conglomerate building has fallen out of favor. It didn’t really work. Surprise surprise: being good at one thing doesn’t mean you’ll be good at doing another. In fact, there’s probably some Dunning-Kreuger effect at play: you know just enough to get overconfident and make bad decisions.

But that doesn’t mean that conglomerates are dead. Both of us are fascinated by the new breed of modern conglomerates.

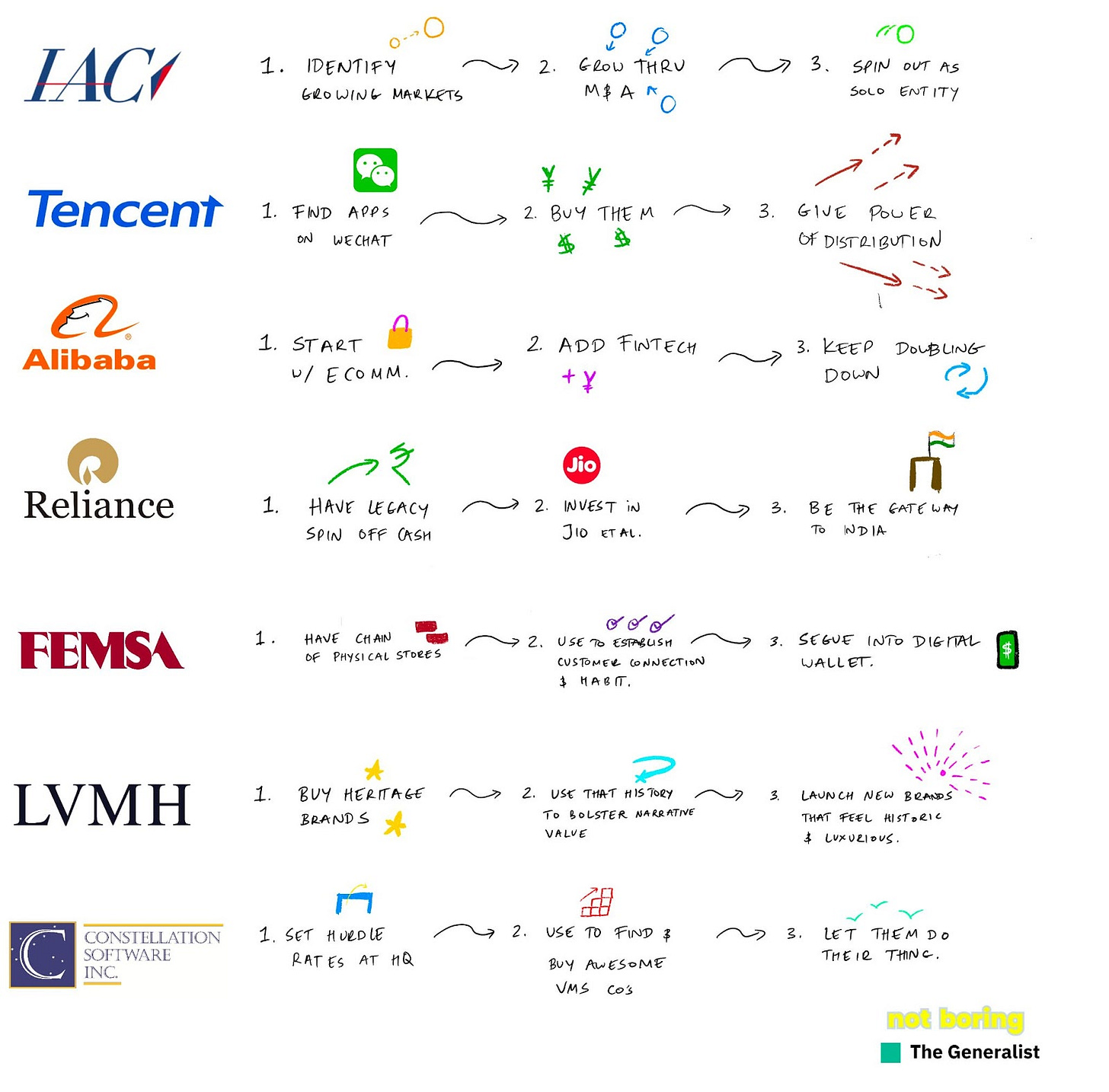

Mario has written about IAC, Constellation Software, and LVMH. Packy has written about Tencent, Alibaba, FEMSA, and Reliance.

The difference between those conglomerates and Tata is that those conglomerates have a thing.

IAC has a playbook for winning on the internet: Identify, Accumulate, and Spin-Off.

Tencent has a Traffic + Capital Flywheel -- find hot companies on WeChat, invest in them, and give them a distribution advantage.

Alibaba started with ecommerce, and expanded into fintech to serve its core.

Reliance leveraged cashflows from legacy businesses into Jio and Retail, its farm-bets on the future, and serves as the Gateway of India for foreign tech giants.

FEMSA has a chain of Oxxo convenience stores, close to its customers, that serve as a physical version of the internet in Mexico and a jumping off point into a digital wallet.

LVMH buys heritage luxury brands and empowers creatives to drive their vision, unfettered.

Constellation Software acquires vertical market software companies, and lets them operate independently.

The Bobs from Office Space would have a field day with Tata, though.

What would you say you do here?

Tata does a little bit of everything. Cars, steel, hotels, watches, tea, consulting, power, communications infrastructure, TV. Called a “parallel government,” Tata purchased some of its former colonizer’s crown jewels -- Tetley, Jaguar Land Rover -- and looks a bit more like an Indian heritage museum than a modern business. For much of its recent history, Tata has looked backwards. Whereas other conglomerates milk their cash cows to fund the next big thing, Tata uses its own to support a central office that tries to infuse modern best practices into its loose constellation of old and decaying businesses.

Five years ago, Reliance was in a similar situation. The company made its fortune in oil and petrochemicals, and to this day, generates the vast majority of its revenue (69%) and profits (63%) in the Oil-to-Chemicals (O2C) business. But it recognized that those businesses are the past, and tech is the future.

As Packy wrote in Reliance: Gateway of India, Mukesh Ambani’s company sold 49% of its fuel retailing business to BP for $1 billion, and is in talks to sell 20% of its O2C business to Saudi Aramco for $15 billion. Meanwhile, it used the cash that that business spit off, and a mountain of debt, to undertake one of the most aggressive balance sheet investments in corporate history, plowing $32 billion into Jio’s national 4G network before recently selling stakes to a global who’s who of tech and investing giants. Those investments, plus the asset sales, moved Reliance back to zero net debt, ahead of schedule.

Reliance’s transformation is one of the two ways to create a modern conglomerate:

Tech-first: Start fresh, with technology at your core, like Tencent, IAC, or Constellation.

Reinvented: Use the cash and unique assets at your disposal to transform yourself into a tech-first company, and sell whatever you need to make it happen, like Reliance or FEMSA.

Either way, there’s no escaping it: modern conglomerates combine technology and focus on a unique thing. Diversified conglomerates are out; focused conglomerates are in.

Transforming Tata

So what’s Tata’s thing?

Start with the brand: after TCS, Tata’s brand, valued at $20 billion, is its most valuable asset. After 152 years, Indian consumers trust Tata, and that’s likely to be even more true after the group used its heft to support the fight against COVID.

The second piece is India itself. Tata’s brand carries the most weight in one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing markets, one full of tech talent and an internet population that’s expected to reach 1 billion people by 2030.

Next comes Tata’s distribution, which touches nearly every Indian consumer and business in a market in which distribution is a particularly hard problem to solve.

Finally, there’s TCS. It’s not just that the company drives ~90% of Tata Sons’ revenue, but how it drives that revenue. TCS is an IT services and consulting business whose revenues increasingly come from digital transformation work.

So how do you leverage those strengths into one thing, one offering that makes sense to the market? How do you make it easy for people to complete the sentence, “Tata does…..?”

You undergo a digital transformation of your own. In August 2019, Tata launched Tata Digital, a startup incubator inside the 152-year-old behemoth. The logo screams this is not your great great grandfather’s Tata.

To launch the group, Tata tapped homegrown talent, former TCS Global Head of Retail, Travel, Hospitality, and CPG, Pratik Pal. It’s the kind of move we’d normally dismiss: big company taps consultant to lead digital center of excellence. But somehow, it fits. Reinvention is what Tata does.

Tata Digital is tasked with executing the third part of the 3S plan Chandra’s been executing all along: scale. It will build or acquire digital products for Tata Group, and scale them up to internet size.

On the B2B side, the obvious place to start is with TCS itself. Tata should double down on TCS’ dominance and try to disrupt itself from within. Tata Digital and TCS can work together to create products that extend monetization beyond the initial engagement. It might build or buy Robotic Process Automation (RPA) or intelligent automation capabilities that it can sell through its existing global distribution channel. That would add valuable licensing and SaaS revenue to TCS’ already monster business.

It might also build products to enhance the capabilities of many of the Tata Group companies that survive further paring down. Tata Power is going renewable, Tata Motors is embracing the EV revolution, and Indian Hotels will need to better compete with a new class of internet-native competitors like Airbnb. Tata Digital has the potential to support and embolden all of these initiatives (and many more) by providing the right resources and making smart acquisitions.

If Tata manages everything we’ve just mentioned, it would be a meaningfully different and more modern conglomerate. But Chandra has bigger ambitions. He wants Tata to build a Super App.

Super Apps, which bring a wide array of services into one app, are not a new concept. Think WhatsApp meets Uber meets Venmo meets Instacart meets DoorDash (and on and on and on). In China, Tencent’s WeChat and Alibaba’s Alipay are battling for the top spot, along with Tencent-backed Meituan Dianping. In Singapore, it’s Grab. In Indonesia, it’s Gojek. In Latin America, Colombia’s Rappi and Argentina’s MercadoLibre are leading contenders.

Super Apps aren’t even new to India. Alibaba-backed PayTM has a publicly stated mission to become the country’s first Super App, and recently expanded from payments into gaming. Reliance is entering the fray, too, with a powerful partner. Facebook’s $5.7 billion investment last summer was the dowry in an arranged Super App marriage between Reliance’s Jio and Facebook’s WhatsApp. WhatsApp has 400 million users in India, and PayTM had 350 million as of 2019. Those are massive, bigger-than-the-whole-US-population headstarts.

It seems like a me-too, too-late idea. We both dismissed it at first as the kind of thing two ex-consultants, Chandra and Pal, would cook up in a whiteboarding-fever dream. But the more we thought about it, the more we saw the vision.

A Super App would leverage Tata’s unique assets -- brand, distribution, India, and TCS (via Tata Digital) -- and provide a clear focal point for the business. Plus, the Group already has a strong portfolio of retail assets and brands that it can plug in from Day 1. The pieces are starting to come together:

Retail: Tata subsidiary Trent ( the name is a portmanteau for Tata Retail Enterprises) signed an agreement to list all of its brand apps, most importantly Westside, on the Super App. Trent sells fashion, books, music, and more. Online shopping in India is tracking ~8 years behind China, after growing from 1% penetration in 2012 to 11% in 2019. It’s a huge growth opportunity.

Healthcare: Tata is in the final stages of acquiring online pharmacy 1mg. Tata’s ability to roll out the first CRISPR-based COVID test, along with its relief efforts, should give it some credibility in the medical space among Indian consumers. India still only spends 3.6% of GDP on healthcare, lagging the US (16.9%), Germany (11.3%), and China (5%).

Finance: Aside from payments, an important missing piece, Tata has an Ant-lite suite of financial offerings, from mutual funds to insurance products.

Groceries: Tata Digital invested around $200 million into BigBasket, India’s largest online grocery platform, as part of a plan to acquire a 60% stake in the company for $1.2 billion. It will buy out Alibaba’s share as part of the deal. It’s making the acquisition despite the fact that BigBasket is competitive with Trent’s Starquik service.

That last point is sneaky huge, and almost Tencent-like. It turns one of Tata’s biggest weaknesses -- it’s decentralized, non-controlling corporate structure -- into an advantage.

Verticalization and integration are in Reliance’s DNA. Decentralization and loose control are in Tata’s. Whereas Reliance will push its own products and services through its Super App, even when they’re not the best on the market (as they’re not in many categories), Tata has publicly stated that it wants to take a more open, partnership-driven approach to its own offering.

That should be Tata’s thing: a decentralized constellation of products and services, delivered by a trusted brand, that make Indian consumers’ lives simpler and more convenient.

Intriguingly, while that no longer works so well for a modern conglomerate of capital intensive companies competing with global alternatives, it works perfectly for Super Apps. These next-gen omni-killers compete domestically based on the breadth and quality of their offerings.

Reliance’s strategy was smart: be the Gateway of India for two of the world’s leading tech companies -- Facebook and Google -- and build or acquire products that serve all of the Indian consumer’s needs.

Tata can counterposition against them by working with everyone else. Internationally, that means serving as a more open entry-point for the rest of the world’s tech companies. Domestically, it means using some of those sweet, sweet TCS dividends to invest in and support Indian startups. The country is becoming a unicorn factory: last month, six Indian companies became unicorns in four days. Tata should lean in if Reliance won’t.

There will be challenges -- Tata doesn’t do messaging, social, or payments, all glue that hold a Super App together. But that lack of homegrown solution offers opportunities, too. After listening to Balaji Srinivasan on the Tim Ferriss Show, for example, we wonder if Tata won’t lean into its decentralization thing even further. What would it look like if Tata used its brand trust to help India, and its people, take advantage of the opportunity to use crypto to become the world’s third superpower?

While that may sound faintly ludicrous, and out of keeping with a tech consulting and industrial company, it’s exactly the kind of visionary move on which Tata was founded. Jamsetji himself would be proud.

How did you like the Not Boring x The Generalist collab?

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday,

Packy

Share this post