Shein: The TikTok of Ecommerce

The Quiet Chinese Quindecacorn America’s Gen Z Shoppers Are #Addicted To

Welcome to the 1,502 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! Join 48,890 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Note: We were writing and editing down to the last minute, so no audio version today.

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by… It’s Not Magic. It’s Supernormal.

Do you suffer from an extreme case of Zoom fatigue? Does the sound of a “ping” make you cring(e)? Do you dream of becoming a silent monk and never speaking to anyone ever again?

Supernormal has one word for you: async.

If you’re one of the “average knowledge workers” who checks a chat app or email every six minutes, it’s time you talk to your boss (or reports, or collaborators, or therapist) about moving some of your work async.

We all know it: we can’t keep working like this. The async revolution is coming. Hop on board and reclaim your day with Supernormal, the hub for async collaboration.

Supernormal loves the Not Boring community! Use this link to sign up and you’ll get a special welcome video just for you from the founders:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

If you’ve been reading Not Boring for a while, you know that I love studying Chinese tech giants. It’s like peering into the future. So when Matthew Brennan reached out to ask if I wanted to collaborate on a piece about a company that’s flying under the radar “almost exactly like TikTok in 2019,” I jumped at the chance.

Matthew should know what he’s talking about. He wrote the book on TikTok — literally, it’s called The Attention Factory. Born in the UK, Matthew has been living for China for over a decade, and is an expert on ByteDance, Tencent, and China tech more broadly. When I wrote about Tencent, I leaned heavily on his work. He’s starting a China ecommerce Substack dissecting new trends and innovations in retail, ecommerce, and brands coming out of mainland China:

I can’t believe I’d never heard about today’s company before. It’s a juggernaut, and it’s changing the face of ecommerce. You’ll be hearing a lot more about this company, just remember you heard it here first.

Let’s get to it.

SHEIN: The TikTok of Ecommerce

The list of the world’s most valuable startups is filled with familiar names: Ant, ByteDance, Stripe, SpaceX, Didi, Instacart. If you scroll down a bit, you’ll find a company that you’ve either never heard about or can’t avoid, depending on whether or not you’re a Gen Z shopper.

Shein (pronounced She In) is the fastest-growing ecommerce company in the world. It reportedly did almost $10 billion in revenue in 2020, and has grown over 100% for each of the past eight years. The company is based in China, yet spurns its local market in favor of selling abroad. Shein sells into nearly every other major market in the world, with the notable exception of India, where it was banned along with TikTok and 57 other Chinese apps last June.

The tech and financial press, usually so infatuated with highly-valued Chinese tech companies, doesn’t talk about Shein much. (Of course, Acquired and Tech Buzz China’s Rui Ma and Ying Lu were ahead of the curve and discussed Shein earlier this month.) Shein wants it that way, it’s an unbelievably private company. But if you’ve spent much time on Instagram or TikTok, you can’t escape it. Influencers from Addison Rae and Katy Perry to Lil Nas X have worked to make Shein’s clothing a mainstay in every Gen Z closet from the United States to the United Arab Emirates. When I asked Puja if she’d heard of Shein, she told me of course, “I have a bunch of Shein stuff. You know that green and white bathing suit? Shein.”

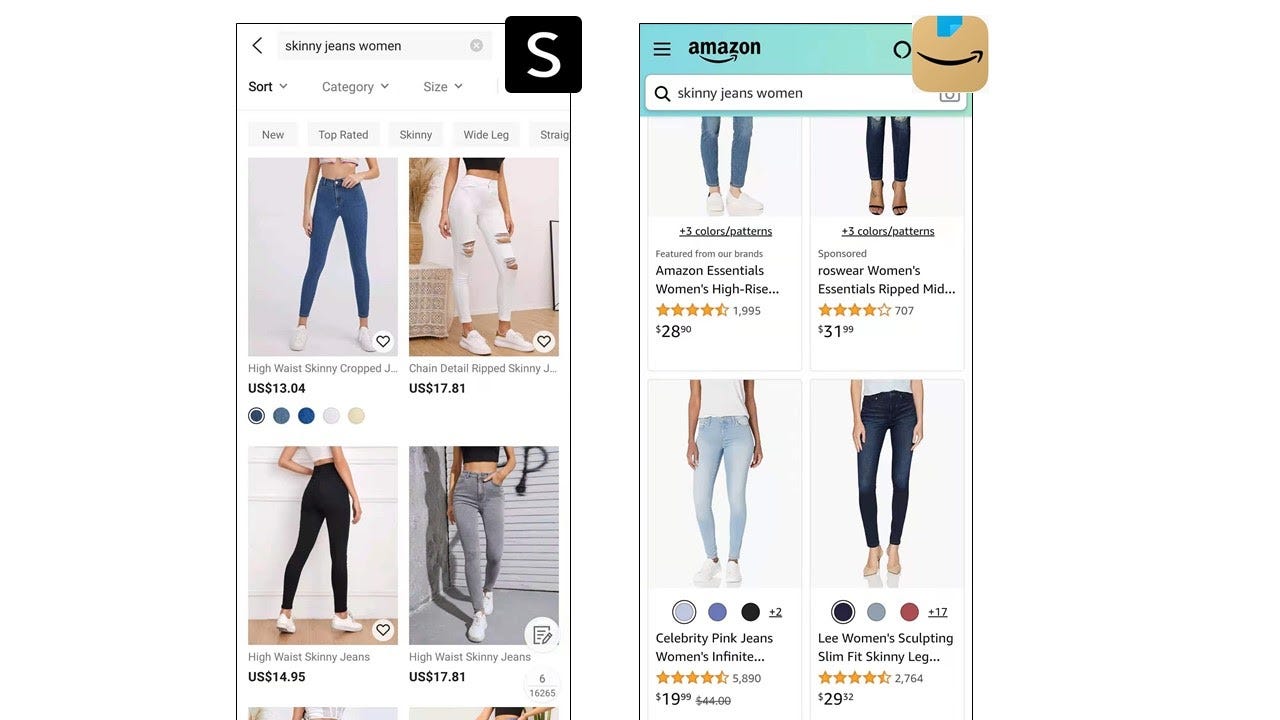

There’s a reason why Gen-Z is infatuated with SheIn — those prices — tops for $7, dresses for $12, jeans for $17, coats for $28. SheIn makes Amazon look positively expensive.

Run a search for “addicted to Shein” on Twitter and you get a sense that this company’s user retention metrics might be Juul-in-2018-good.

The numbers back up the hype. These are just a few mind-blowing facts about Shein:

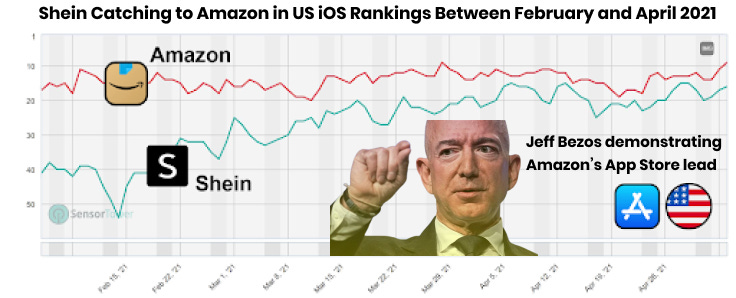

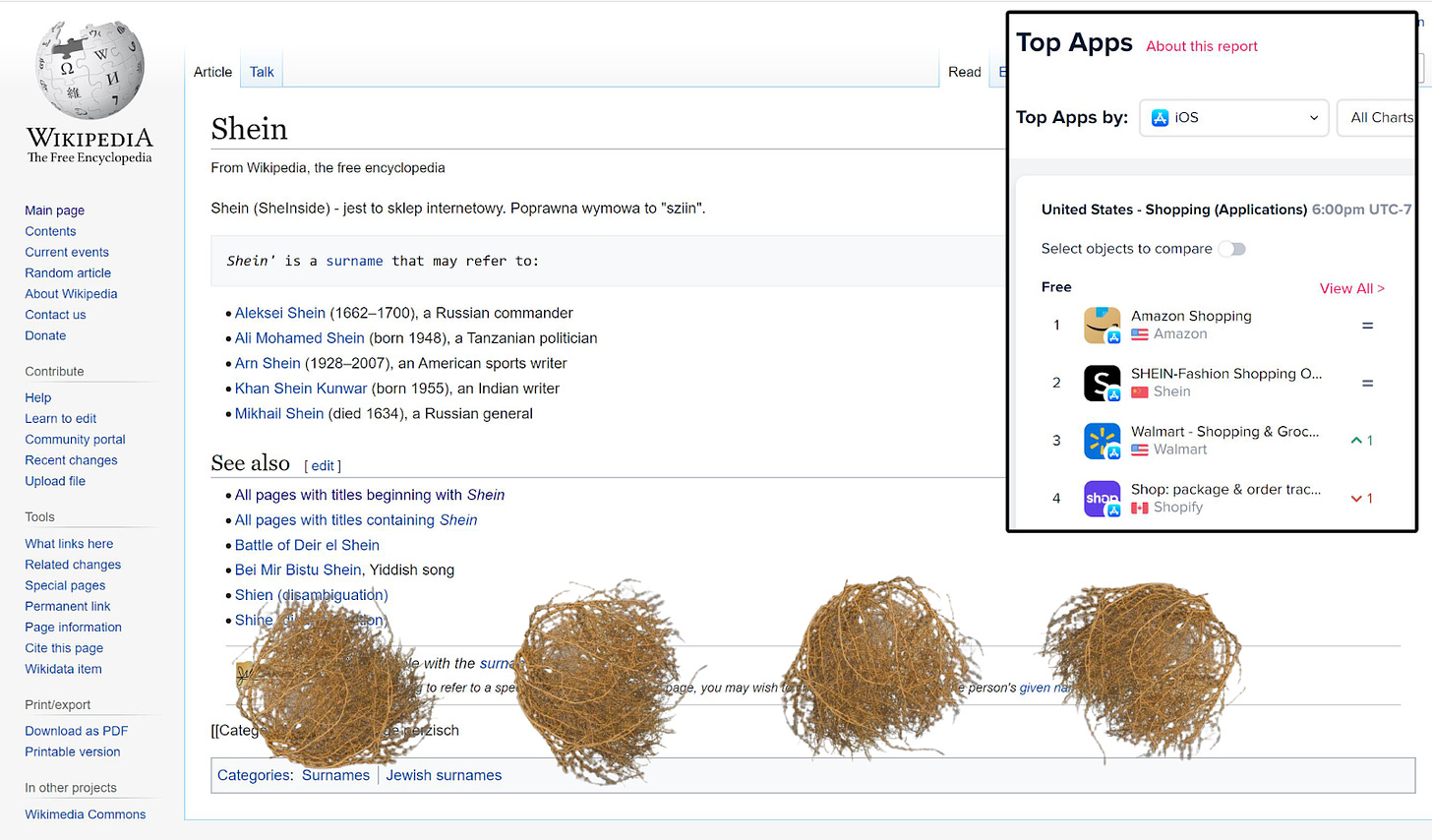

Shein ranks as No.1 in the iOS App Store’s Shopping category for 56 countries, and garners a top 5 spot for 124, out of total 174.

Since mid-February, Shein has seen an unbroken run of being ranked second only after Amazon for shopping apps in the United States.

A recent survey of American upper income teens by investment bank Piper Sandler also ranked Shein as 2nd after Amazon for most popular shopping website.

Shein’s website ranks no.1 in the world for web traffic in the fashion and apparel category, according to SimilarWeb, putting them ahead of household names Nike, Zara, Macys, Lululemon and Adidas.

The average duration of a site visit is estimated at 8 mins 36 seconds, higher than every major US fashion brand.

A recent report claimed Shein was the most talked about brand on TikTok in 2020.

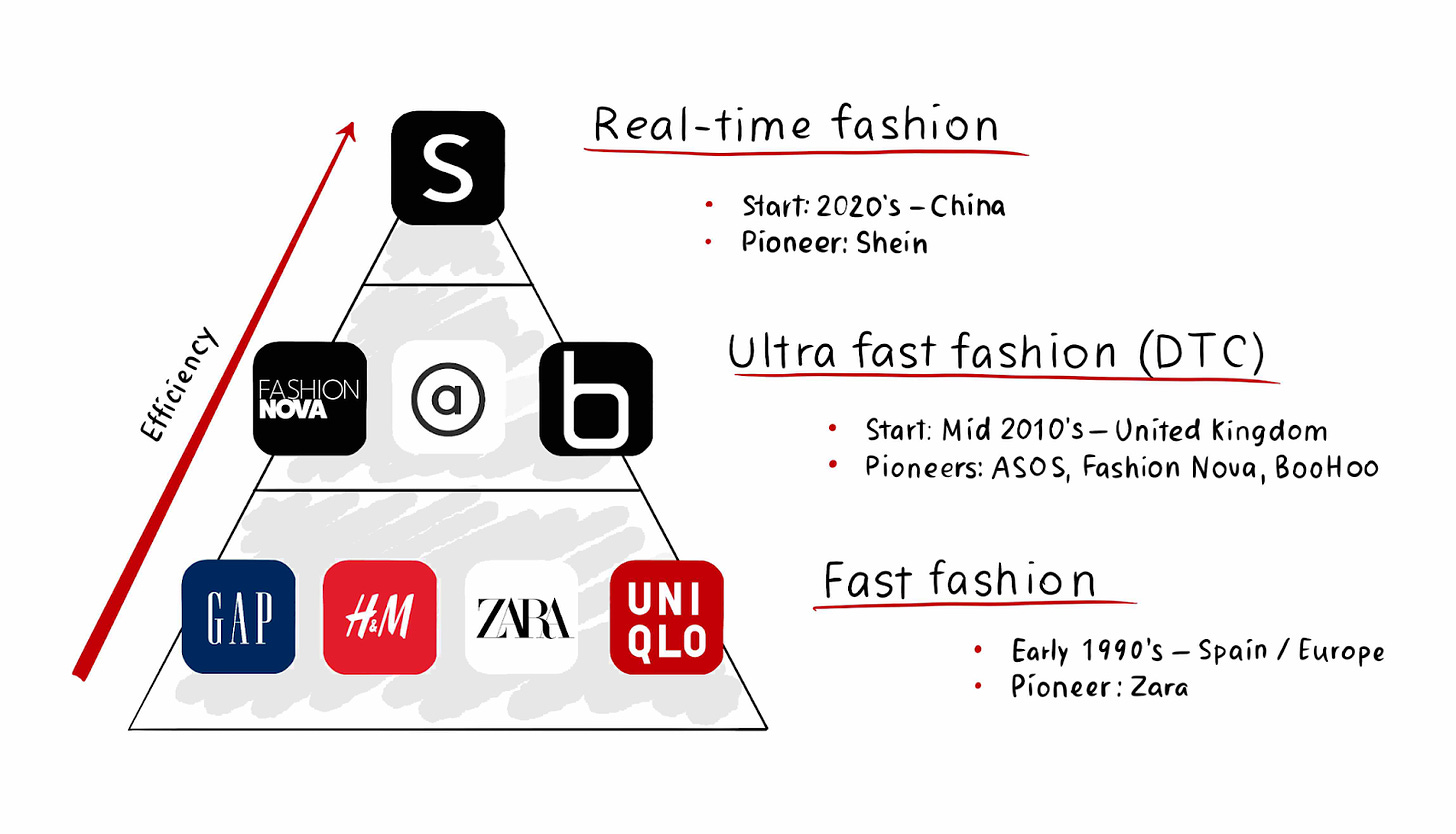

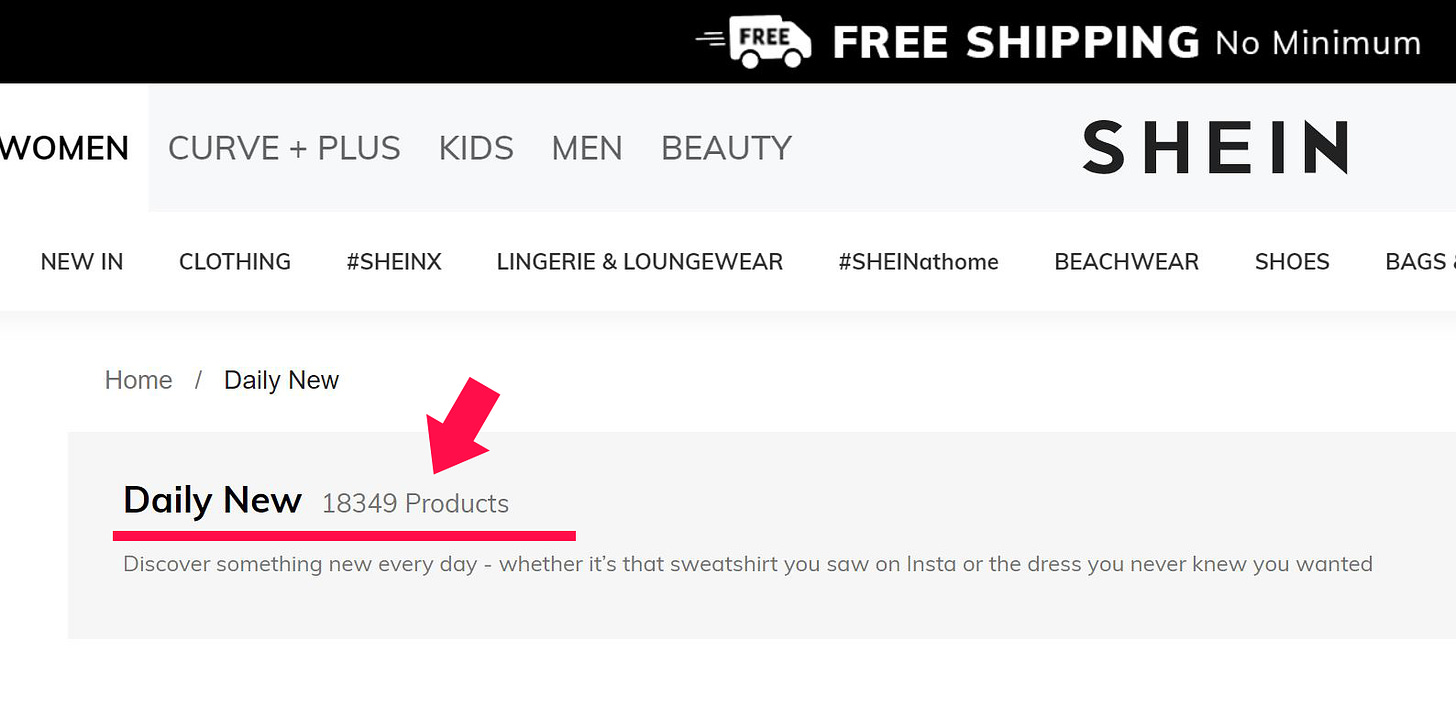

When it is discussed, Shein is compared to fast-fashion or ultra-fast fashion brands like Zara, H&M, Fashion Nova, or ASOS, but it’s… faster. A recent feature by data analytics firm Apptopia concluded that, “Shein is so far ahead of its direct (fashion industry) competitors that it's difficult to even compare them.” It’s essentially defining its own category, which Matthew has coined Real-Time Retail.

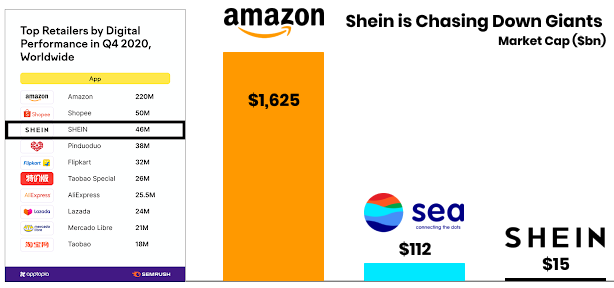

Shein won’t stay a secret in tech for long. In January 2019, it raised $500 million from Sequoia China and Tiger Global at a $5 billion valuation. In August 2020, it raised an undisclosed amount from an undisclosed investor at a $15 billion valuation. Is that Masa’s music?

Today, Matthew and I are going deep to uncover most of what we could find on the company, its backstory, growth, strategy, challenges, and future. We’ll cover:

Shein In Context

Why You’ve Never Heard of Shein (Hint: they didn’t want you to)

A Short History of Shein

Why Shein is a Big Deal

Shein’s Secret Sauce

Criticism and Controversy

The Big Picture

It’s our pleasure to introduce you to Shein.

Shein In Context

Apparel is one the largest retail categories, but it's also really tough. Fast fashion is a $35 billion segment within a broader apparel and footwear market expected to crack $3 trillion this decade -- with a ton of unique challenges:

Fast Turnover: Clothes are seasonal by nature, and fashions change faster than ever. Many start online, inspired by influencers and celebrities.

Regional tastes: What’s popular in the Middle East (one of Shein’s top markets) or South America may have little relation to what’s trending in America or Europe.

Huge Variety: A basic t-shirt might come in 10 colors, 6 sizes, and 2 necks. That’s 120 SKUs for just one product.

Labor intensive: Garment factories aren’t full of robots, they’re full of people with sewing machines.

High returns: Items bought online may not fit correctly or look as good on someone as they’d hoped, and ecommerce is unable to digitize changing rooms.

Predicting Demand: A retailer needs to warehouse inventory that accounts for all of the above, across a huge number of different products.

Fashion is a radically different and inherently challenging product category. Anyone who can predict demand more accurately, test more nimbly, and dial up production of popular SKUs faster than others, thereby reducing waste, inefficiencies and markdowns, will hold a huge advantage over competitors.

That was the secret to Amancio Ortega’s success. The 10th richest person in the world, worth $86.9 billion, Ortega built his fortune through Inditex, the Spanish fashion conglomerate he started in 1985.

If you’ve never heard of Inditex, you’ve heard of its star brand: Zara which pioneered the “fast fashion” category since the 1990’s. It scans the globe for fashion trends, designs clothing with lower-priced materials based on those trends, and gets pieces from drawing board to store floor in three weeks. Compared to traditional retail, fast fashion was a revelation. With the advent of fast fashion, a regular person could wear the latest trends and turn over their wardrobe as frequently as a celebrity, without breaking the bank. Zara pioneered the trend, and while it has an online presence, the company is defined by its retail footprint of nearly 3,000 stores.

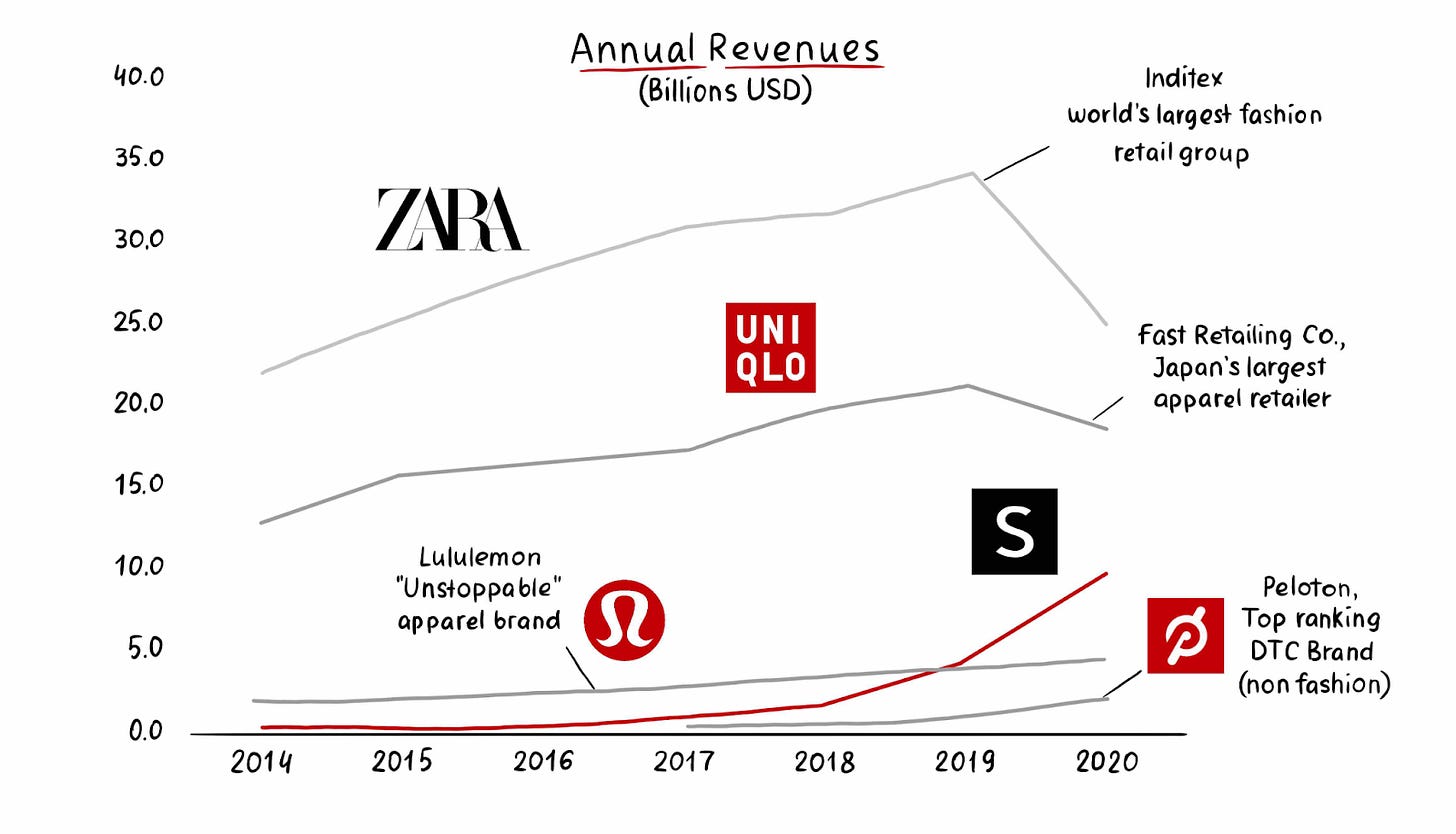

While Inditex is the biggest fast fashion brand, worth over $120 billion, it’s not the only game in town. Its model forced older brands like Gap, H&M, and Uniqlo to pivot into fast-fashion, and a newer breed of companies like Fashion Nova, Boohoo, and ASOS largely cut out physical retail and middlemen in an evolution called ultra fast fashion, the DTC version of fast-fashion. ASOS and Boohoo are publicly listed companies already, with 2020 revenues of $4.6 billion and $1.6 billion respectively and YoY growth rates of 19% and 44% growth. ASOS’ market cap is $7 billion, and Boohoo’s is $5.7 billion.

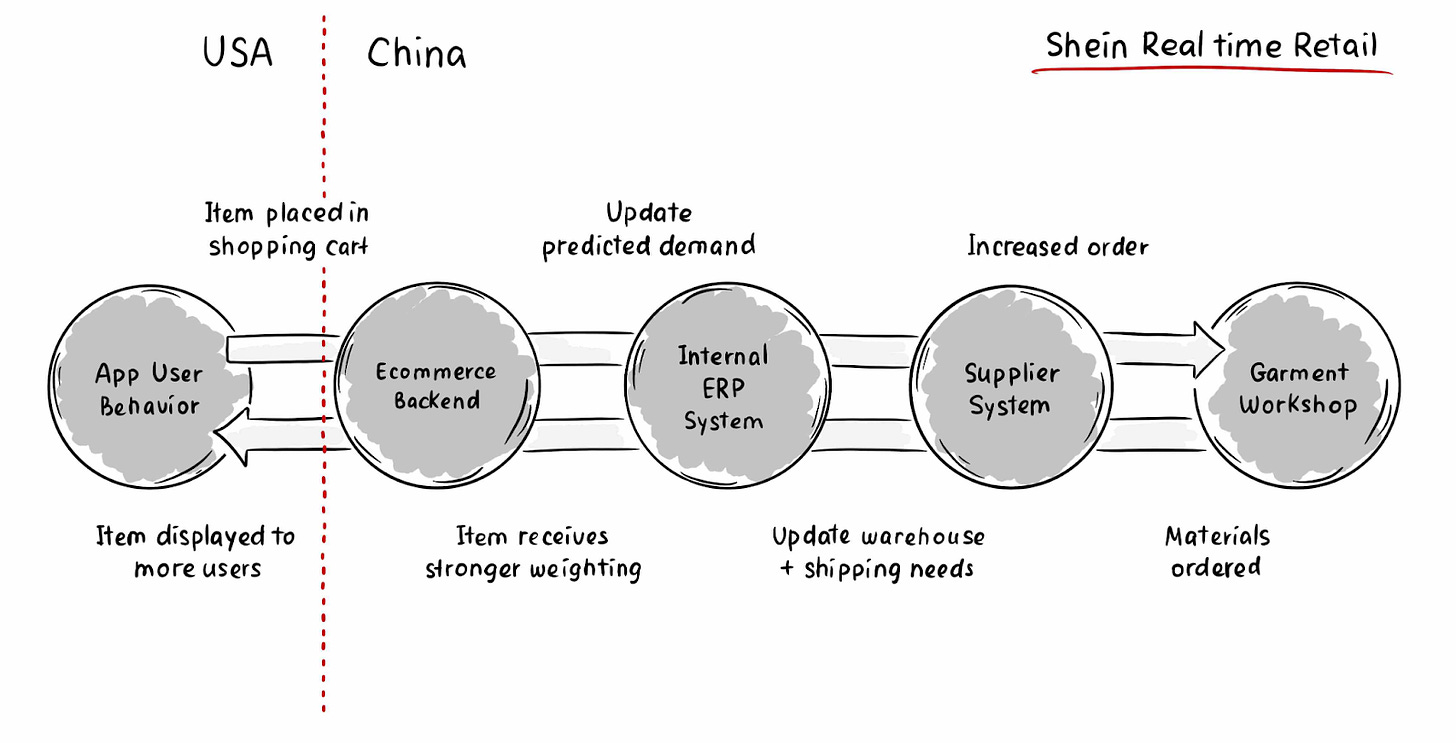

Yet we now live in the internet age of A/B tests, big data, AI algorithms, computer vision, and automated supply chain cloud software systems. Could it be possible to create a much faster pure online system? One that’s faster than ultra-fast? One that didn’t rely on personal relationships or the instincts of a great founder, but instead crunched huge amounts of data to track changes in fashion trends globally in real-time? One that A/B tested massive numbers of SKUs on a daily basis and then updated order numbers across hundreds of factory floors in real time based on website and in-app user behavior? Would it be possible for someone to base themselves among China’s largest cluster of apparel factories previously using very little software and digitize the entire production process? What would that look like?

It would look a bit like this.

At the Sohn Conference in September 2020, at which hedge fund managers present the best ideas they’re willing to share, Hong Kong-based fund Anatole Investment Management presented his case for shorting Inditexdue to the rise of the “new breed” of online players from China. “Zara is a legacy player which is going to be crushed by fast fashion 2.0,” Anatole Chief Investment Officer George Yang told attendees.

Chief among the new breed of online players from China is Shein. The real-time retail model that Shein pioneered cuts the time from design to production from three weeks to as little as three days (although typical times are 5-7 days). Shein cuts out any of the remaining middlemen, and has built an advanced cross-border version of the Consumer to Manufacturer (C2M) model that Pinduoduo pioneered. It plugs directly into competitors’ websites and Google Trend Finder to understand what’s in-fashion, designs quickly, and links in-app and on-site user behavior to the backend to automatically forecast demand and adjust inventory in real-time, aggressively pushing ads through its paid acquisition and influencer referral machine the whole time.

We’ll dig more deeply into Shein’s magical machine in a little bit, but for now, know that:

It can produce a wider variety of relevant products more cheaply and quickly than competitors (although delivery times are currently still an issue).

It’s working.

According to Chinese media sources, in 2020, Shein did almost $10 billion in sales, up from $4.5 billion in 2019. Meanwhile, largely due to the pandemic, which prevented people from shopping in stores around the globe, Zara and Uniqlo’s revenues tanked last year.

While some of Shein’s relative outperformance can be attributed to COVID, there’s a clear shift underway. Shein is picking up steam while the OG fast fashion brands slow. Using site traffic and app ranking data as a proxy to track the health of Shein’s business so far in 2021, we can be fairly confident its growth hasn’t slowed as the world reopens. It may have even sped up.

After hockey stick download numbers reminiscent of TikTok’s rise in 2018/2019, Shein is now the #2 most downloaded shopping app in the world, and #3 in the US over Q1 2021. Between February and April, Shein has made big moves towards catching up to Amazon in the US iOS App Store rankings, a particularly impressive feat given that Amazon sells everything to everyone, and Shein sells clothes to (mainly) Gen Z women. Hot vax summer, indeed.

Globally, Shein sat above Flipkart and Pinduoduo and just behind Shopee for most new digital shoppers onboarded in Q4 2020. Shopee is the flagship ecommerce platform of Sea Limited ($SEA), the world’s best performing large cap stock in 2020 with 880% growth. Shein passed Shopee in Q1 2021. Its digital performance is on par with, or better than, some of the world’s largest companies by market cap, potentially a leading indicator of future performance.

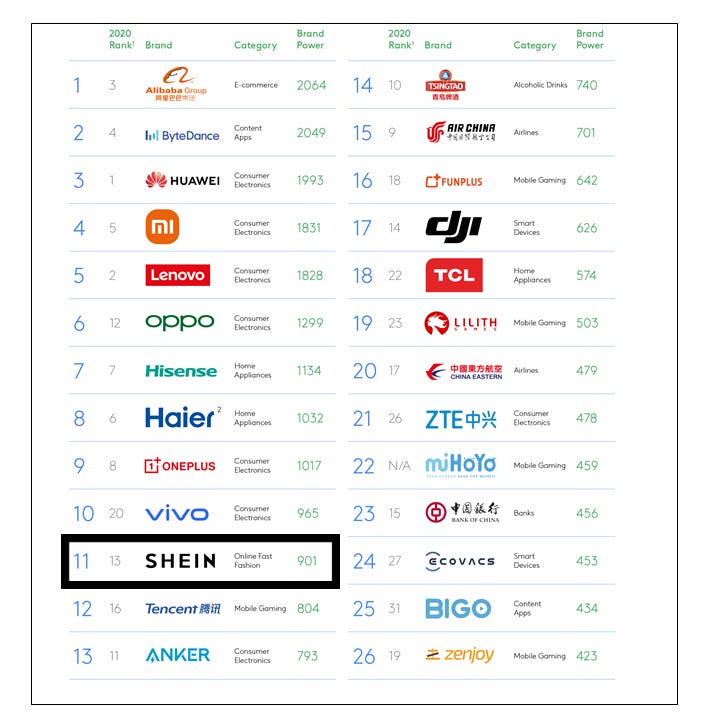

Shein’s performance on the global stage isn’t just impressive among ecommerce companies, though. In Google and Kantar’s 2021 BrandZ Report, released a few days ago, Shein ranked No.11 in the 2021 annual index of China global brands, one spot above Not Boring favorite Tencent. The report singled out Shein for praise, claiming it’s brand power had grown the most of any company in the ranking.

All of which raises the question: if Shein is the fastest-growing ecommerce company in the world, the 11th most valuable Chinese brand globally, doing $10 billion in revenue, backed by Sequoia and Tiger, and on a path to revolutionize the fashion industry, why have most of us never heard about it?

Why You’ve Never Heard of Shein

“What is SheIn? I don't know much.” When you discuss SheIn with Internet people, most of them will give this answer.

-- LatePost

Packy here. I am a professional tech newsletter writer. I’ve written almost 20,000 words about Chinese giants Tencent and Alibaba. I am an Internet people. And I’d never heard of Shein either.

To be fair, though, no one really has. When I asked Rui Ma, an investor and the host of Tech Buzz China, what she thought of Shein, she replied with one word: “mysterious.”

Turns out, that’s very much by design. The company is hyper-secretive. Its founder, Chris Xu, doesn’t give interviews. There are like three pictures of the guy online...

… and the middle one doesn’t even look like the same person.

This is the Wikipedia page for Shein, a $15 billion company that’s ranking above Walmart, Shopify, and Nike on the American App Store shopping category.

Within China, Shein has built a reputation for rebuffing journalists, avoiding investors and keeping the lowest profile possible. The Shein brand is basically unknown to Chinese consumers as the company’s business is firmly focused on exporting abroad. To date there has been only one detailed article online (link in Chinese) documenting the company’s founding story and first forays selling wedding dresses. Shein’s “opaque nature” makes it “very difficult [for industry analysts] to cover,” admitted a global retail industry research director in a recent fashion industry feature.

Why does a company that’s so omnipresent on social media keep such a low corporate profile?

For one, when you have a business like Shein’s, you don’t need to waste time courting investors. In fact, according to LatePost, “A number of first-tier venture capitalists in China had attempted to approach Shein in light of its retail promise. But they made these moves too late; by the time they established contact, the company had closed funding rounds.”

(Side note: that Tiger Global was able to invest, as an American fund, when the top local funds didn’t even know that Shein was raising, is absurdly impressive. How do you compete with that?)

Avoiding aggressive VCs isn’t a compelling enough reason for total secrecy, though. A more convincing one is not who the company raises from, but who it does and does not sell to.

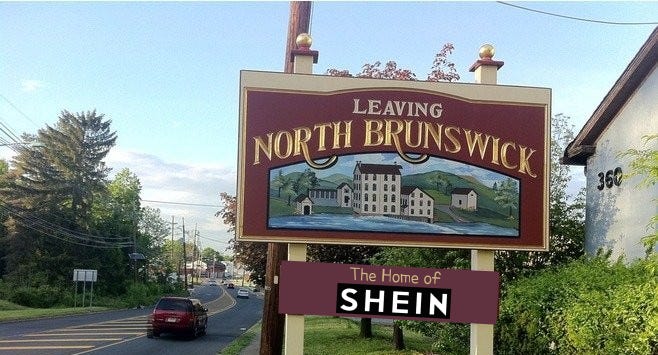

Shein describes itself as an “international B2C fast fashion e-commerce platform” with business in more than 220 countries and regions around the world. Nothing Matthew could find on their official website, app or social media accounts references the company’s Chinese origins. In fact, the company is so serious about hiding its Chinese roots that it voluntarily claimed to be from New Jersey. Previously, the About page of Shein’s official website said the company began as “a small group of passionate fashion loving individuals in North Brunswick, New Jersey.” This has since been removed.

Shein’s otherwise detailed shipping status updates use generic terms such as “source country” and “port of departure,” avoiding reference to Guangzhou or Hong Kong. The company’s logo, branding and products are indistinguishable in their professionalism and quality from global industry peers.

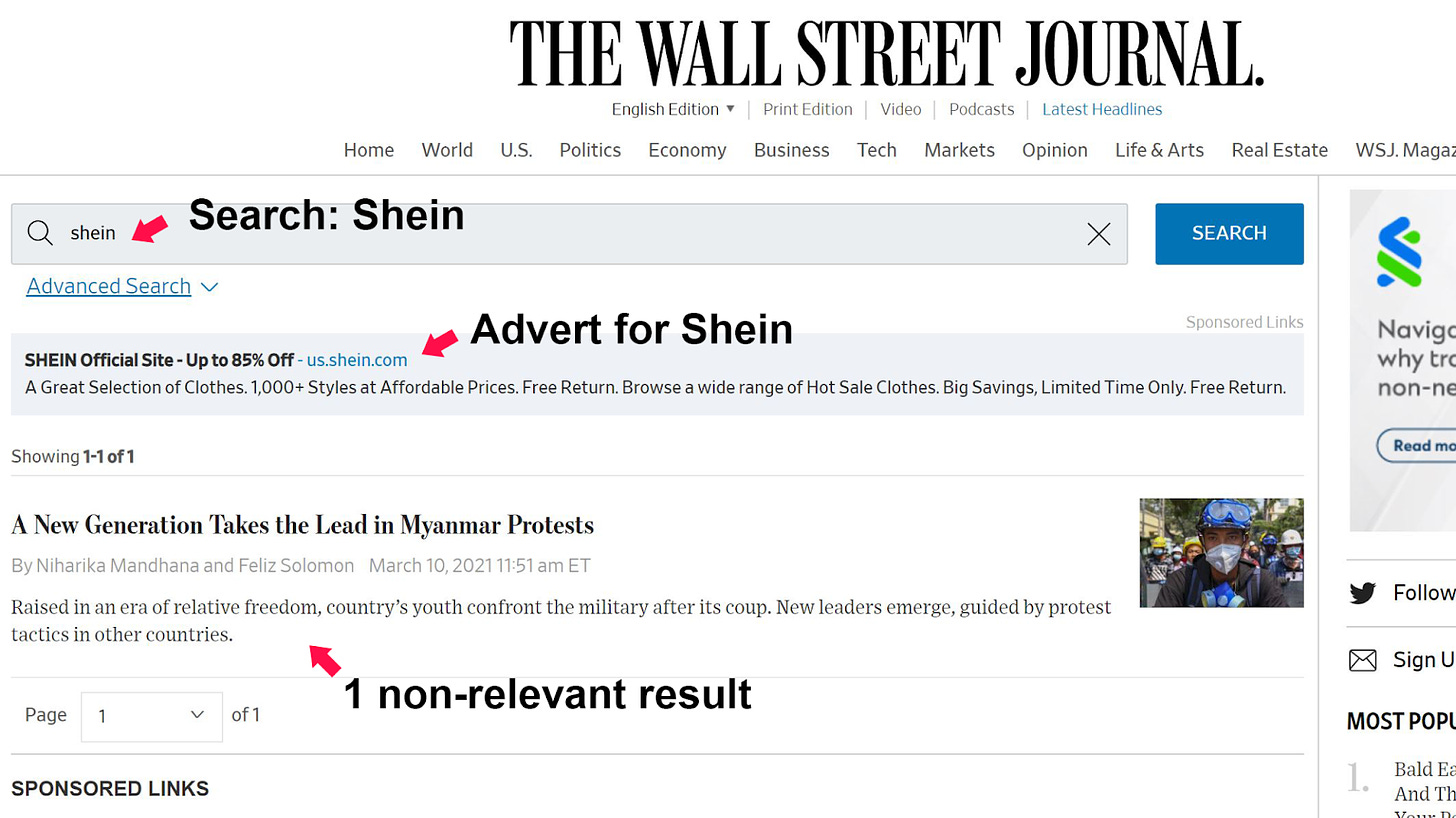

Thus far, it’s worked. American politicians and media have been asleep at the wheel. It’s missing from apparel brand rankings . Run a search for “Shein” on the New York Times site--nothing. Wall Street Journal--nothing. But Shein’s still running ads against those searches.

When they wake up, expect the inevitable headlines like “Opaque Chinese Company Holds Payment Data and Delivery Addresses on Millions of Americans.” Such is the regrettable current state of Sino-American relations.

But there’s a less sinister explanation, as well. The company doesn’t sell in China, so local press coverage wouldn’t help sales, but it does sell in 220 countries around the globe. Those countries are not as familiar with the C2M model and are still skeptical about the quality of low-cost Chinese goods. Consumers might be less likely to buy if they knew they were essentially buying direct from Chinese manufacturers.

Shein doesn’t have a style. It doesn’t try to impose its taste on global consumers. It doesn’t even have its own taste. It’s a mirror that reflects each country’s current style back to it, in real-time, based on data alone. Remaining generic, storyless, and nationless allows it to project whichever image is needed in the moment on its loose army of local influencers across the globe.

Maybe that’s just us filling in the blanks in a way that fits our own story, but that’s kind of the point.

From the beginning, Shein was built to sell abroad. Its secrecy extends to its history. This story begins in different places, depending on who you believe.

A Short History of Shein

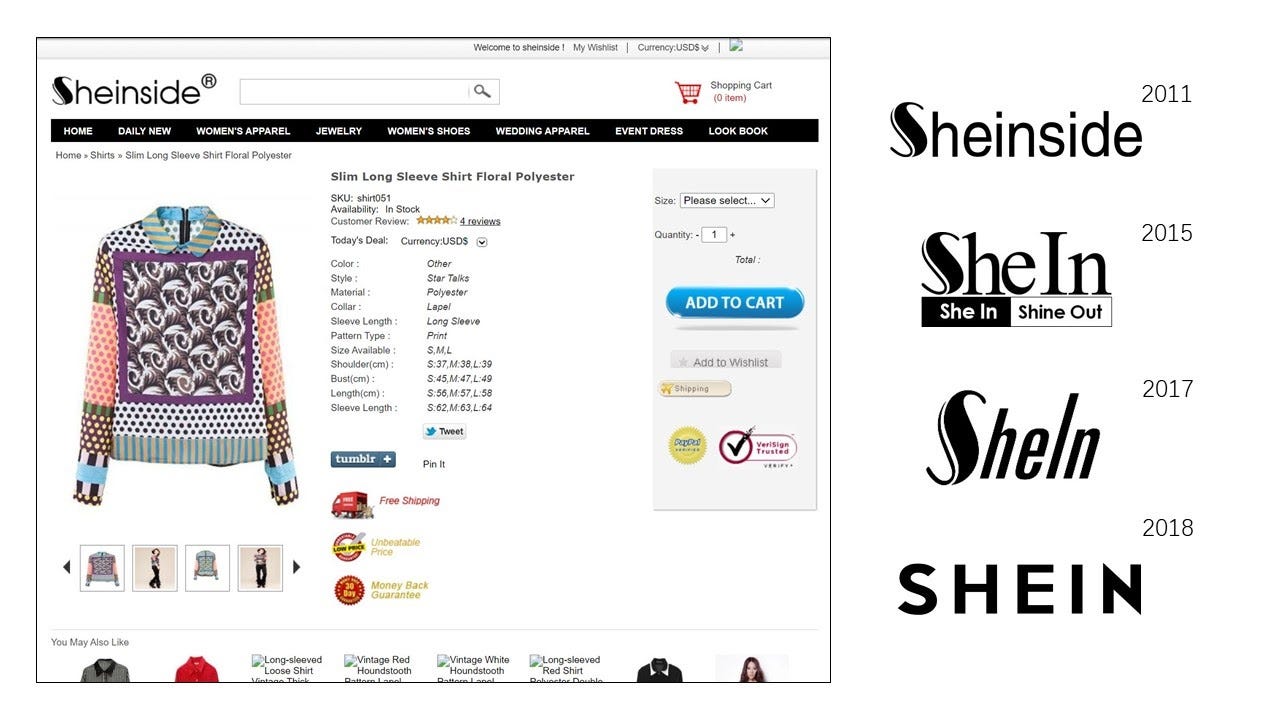

According to Forbes, (most likely citing the company’s own press releases), “The story really starts at the beginning of 2012, when notoriously hard-working founder and CEO Chris Xu... an American-born graduate of Washington University, gave up his wedding dress business to acquire the domain Sheinside.com.” Yet according to Pandayoo, and most Chinese media, Xu was “born in 1984 in Shandong Province, China and graduated from Qingdao University of Science and Technology in 2007,” after which he moved to Nanjing. Mysterious.

Nanjing isn’t exactly known for being unicorn central. It’s no North Brunswick either. Perhaps Nanjing is more akin to a Philadelphia: it’s a large, well-known, and historically important city, but not exactly Shenzhen or Hangzhou when it comes to startups. Yet Nanjing is where the Shein story begins.

Xu served a brief stint working at a cross-border services consultancy in Nanjing where he worked on search engine optimization. Later, Xu and his small team of SEO specialists invested their own money to set up an ecommerce business, Dianwei, which reportedly sold fake goods. After a falling out with his then business partner that we don’t have time to go into, Xu settled on a different model: “customized, special occasion apparel.” Wedding dresses, graduation dresses, bridesmaids, groom wear, formal evening wear; anything that required custom bespoke fit measurement, Xu would do.

During the company’s formative early years of 2008 to roughly 2012, Shein was tiny. A few tens of people specializing in SEO and wedding dresses. But it was a smart launching pad.

Believe it or not, wedding dresses were the first killer category for Chinese ecommerce firms exporting direct to markets like America. These were the early days of China’s cross-border ecommerce industry, when life was so simple, and Amazon had yet to turn into the hot mess of Chinese sellers with strange brand names operating all kinds of black hat tactics that it is today.

The wedding dress model was pioneered by Lightinthebox, whose founder Alan Guo, worked previously at Google China with AI guru and author Kai-fu Li. Alan was inspired to start his company after meeting Thomas Friedman, who had given a speech at Google China on his then latest book, The World Is Flat. The system LightInTheBox pioneered was called “cell-based, flash manufacturing.” Small “cells” of workers, each with a highly-skilled leader, made three to four tailored wedding dresses per day according to the exact measurements that customers provided through the website. The reason for its success: a massive opportunity for price arbitrage.

When Xu entered the space, wedding dresses were the second most in-demand product in the cross-border trade, behind electronics. One SEO expert told LatePost, “At peak demand, one could literally just change the currency denomination of the purchase price from RMB into USD,” meaning a roughly 6.5x price increase. In 2011, the average US wedding dress was $1,166, yet on Chinese-operated sites like Lightinthebox and SheInside (Shein’s original name), the average price was just $209 (18%!). Even with that low price, the Chinese sellers could still make high margins given their manufacturing advantage. Lightinthebox was eventually able to IPO on the Nasdaq in 2013 based on the success of the model. Yet of course, this being China, once word got out how much LightInTheBox was making, a flood of copycats entered the market. SheInside was one of them.

Alongside wedding dresses, Shein also sold normal women’s fashion, which over time became the main staple of their business. At this point in time, Shein’s supply chain was non-existent. Head down to the local wholesale clothing market, buy a bunch of clothes, and upload the information to the website. It was no more complex than the average eBay seller. They didn’t even do photography; the pictures came from the wholesale sellers.

Yet the company started to grow like crazy. Not only was there a big price difference in apparel between China and other markets, but most brands hadn’t really worked out effective strategies for selling clothes online yet. Shein was one of the first apparel companies to use social media influencers as early as 2011. They were one of the first early adopters of Pinterest, which became their top source of traffic during 2013-2014. Even more recently, Shein was early to TikTok marketing, becoming the most talked about brand on TikTok in 2020. Coupled with a founder whose background lies in SEO, you have the makings of an unparalleled online marketing powerhouse.

Shein was far from being the only company to hit upon the power of social media to sell fashion. Around the mid 2010’s, a new wave of direct-to-consumer fashion startups started to gain traction. Pure online brands like Boohoo, ASOS and Fashion Nova also understood the power of social media not only for promotion but also anticipating new trends. Working together with local factories close to their consumer base, this new breed of companies were able to take fast fashion up a notch into “ultra-fast fashion.” Richard Saghian, founder of LA based Fashion Nova described his company’s rise by saying, "We don't even really have a strategy. We grew so fast. We are just grabbing the tiger by the tail." Fashion Nova is currently #1 on 2PM’s DTC Power List, and more than 50% of the top 20 are fashion companies. Shein is mysteriously nowhere on the list.

It’s difficult to tell who inspired who, but it was also around this time of the mid-2010’s that Shein ditched the old buying from wholesale markets model and switched to designing its own clothes similar to their American and European DTC counterparts. Pretty soon, it had a team of hundreds devoted to in-house design and prototyping. An ecosystem of garment workshops and factories started to form around the company. By 2015, the newly rebranded SheIn, moved to Panyu in Guangzhou. Panyu is to clothes manufacturing what Shenzhen is to electronics (i.e. ground zero, global best-in-class supply-chain ecosystem). All of Shein’s suppliers moved with it. It’s not hard to understand why.

Shein had built a reputation for doing something completely revolutionary and unheard of in China’s apparel industry—they actually paid people on time.

But they didn’t stop there. They questioned everything about how a supply chain should work in the internet age from first principles:

What if we actually pay our suppliers on time?

What if we gave them lots of training and support, like we would our own employees?

What if we pay them after 30 days instead of 90?

What if we offer the best suppliers loans to help them expand quickly and grow with us?

What if we broke the culture of relying on personal relationships and backroom deals and instead based everything around transparent KPIs that both sides could monitor in real-time?

What if we built a software platform that allowed us to automate every aspect of our day-to-day dealings with suppliers?

Shein also took on roles and responsibilities traditionally handled by factories such as prototyping, an expensive but necessary step in producing clothes. Shein brought this work in-house, simplifying the relationship while reducing risk and cost for its partner factories. Before long an entire industry was falling over themselves to gain Shein’s business.

In return, there was one requirement: everyone had to use Shein’s supply chain management (SCM) software. Factories couldn’t run their own internal software and Shein’s in parallel. Working with Shein meant an initially uncomfortable level of transparency: plug yourself into the mothership and let Shein track everything.

Fortunately, garment factories by their nature don’t have too many trade secrets to hide. They’re also not typically known for being highly digitalized. In fact, many factories were not using much in the way of software before working with Shein. Suddenly, hundreds of previously undigitalized factories were now hooked up into one brain, one cloud software system.

With the backend starting to take shape, Shein focused on its front-end and brand image.

2015: it rebranded from SheInside to SheIn

2016: it announced a cull of mediocre suppliers, not just the ones producing low-quality items, but also the ones producing low-quality product images

2017: redesigned the website to create a cleaner, more professional look

2018: added swimwear (like Puja’s bathing suit)

2019-2020: expanded into Men, Kids, and Curve to become a one-stop shop

During this period, Shein also started raising a lot of money. Until 2015, it had only raised $5 million in a Series A led by JAFCO Asia. In 2015, it raised $46 million at a $230 million valuation from Greenwoods and IDG, which allowed it to gain a foothold in the American market through the acquisition of LA based DTC fashion brand MakeMeChic. It also acquired a local competitor, Romwe, founded by Xu’s old business partner. After rebranding, Shein was ready for the big time.

Sequoia China came in with an undisclosed Series C investment valuing the company at $2.5 billion in 2018, then doubled down by leading a $500 million Series D with Tiger Global, valuing the company at $5 billion, in 2019. Back-to-back rounds in Chinese Unicorns aren’t new for Sequoia: it also led the Series C and Series D for TikTok parent company, Bytedance.

Its most recent raise, an undisclosed Series E investment from an undisclosed lead, gave the company the $15 billion valuation it sports today.

From a small wedding dress maker, Shein has grown into a big deal. It’s winning global real-time fashion. But that’s just the beginning.

Why Shein is a Bigger Deal Than People Realize

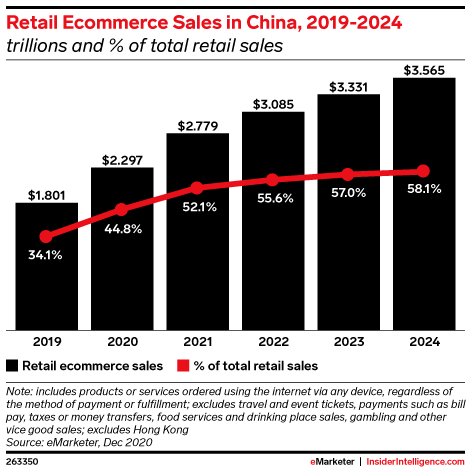

Looking at ecommerce in China from the west is almost like looking into the future.

Even after COVID, eMarketer projects that 2021 ecommerce penetration will be 15% in the US and 12.9% in Western Europe. It expects ecommerce penetration in China to pass 52%.

Demand drives innovation. Ecommerce business models and tactics are more advanced in China than in the US, and are starting to be adopted here:

Alibaba is the foundational Chinese ecommerce company, expanding from B2B wholesale into a wide array of ecommerce and financial products. Packy explored its rise in BABA Black Sheep. The company is worth $568 billion, not including Ant Group.

Pinduoduo, launched in 2015, pioneered the C2M model and has ridden it to over $9.1 billion in 2020 revenue, $7.3 billion of which is from advertising, and a $148 billion market cap. Italic is building a C2M juggernaut here, as explained on Invest Like the Best.

As Lillian Li and Packy wrote in Agora: Bull and Bear, the Chinese market livestreaming e-commerce is estimated to be worth RMB 1.05 trillion ($165bn USD). There is a wave of startups attempting to bring the model to the US, Benchmark-backed Popshop chief among them.

Meituan-Dianpinggrew from a Groupon clone and food delivery app into an “Amazon for Services” worth $190 billion. Much of the bull case for DoorDash and other US-based food delivery apps is that they might become the next Meituan, dominating the market to the point that they’re able to charge profit-generating prices.

These companies follow a playbook originally written by Amazon: serve the needs of users within a single high-frequency purchase category, and use that category as a beachhead from which to expand vertically (brands) and horizontally (categories).

Amazon famously started with books and became the everything store.

Pinduoduo started with fruit and built its own mobile-first everything store.

Even though Alibaba started broad in B2C competing with eBay, apparel and cosmetics were killer categories that fueled its rise to domination in domestic ecommerce.

Meituan-Dianping parlayed food delivery and reviews into a local services and online travel agency (OTA) superapp.

Most of the Chinese ecommerce companies we’re familiar with are focused on the domestic market. With 1.4 billion people, there’s plenty of opportunity.

But a new generation of Chinese companies outside of ecommerce are building in China for the world. Agora is one, TikTok is another, and Webull is stealing customers from Robinhood. Companies built in China have the opportunity to be truly global; they can access both the global and Chinese markets, something that’s much more difficult for American companies not comfortable with what it means to operate in China.

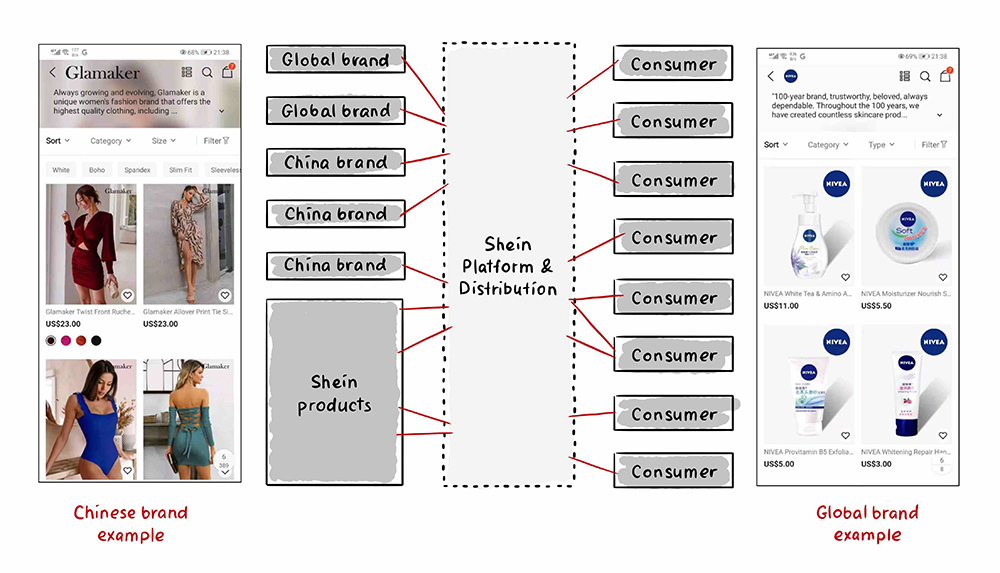

Like its larger Chinese counterparts, Shein is starting with a niche — women’s clothing — and has expanded into a one-stop destination for basically all clothing/cosmetic needs. The temptation to keep expanding categories must be almost unbearable. Compared to other Chinese ecommerce companies, Shein has actually been remarkably disciplined in sticking to just clothing for so long given that the key to expansion is having enormous traffic, something Shein now has in spades.

Clothes shopping is a high frequency activity for Shein’s target demographic, (see “addicted to Shein” tweets) similar to food delivery for Meituan and fruit for Pinduoduo. Enormous traffic at high frequency means more opportunities to sell people more products. Just as Meituan and Pinduoduo expanded from the initial wedge to serve the Chinese market in more ways, it’s hard to think Shein won’t also want to become a marketplace for other brands. After digging around among the SKUs, we found a few indications they are already experimenting in this direction.

We’re bullish on Shein’s expansion, because its power doesn’t lie in what it sells, but how.

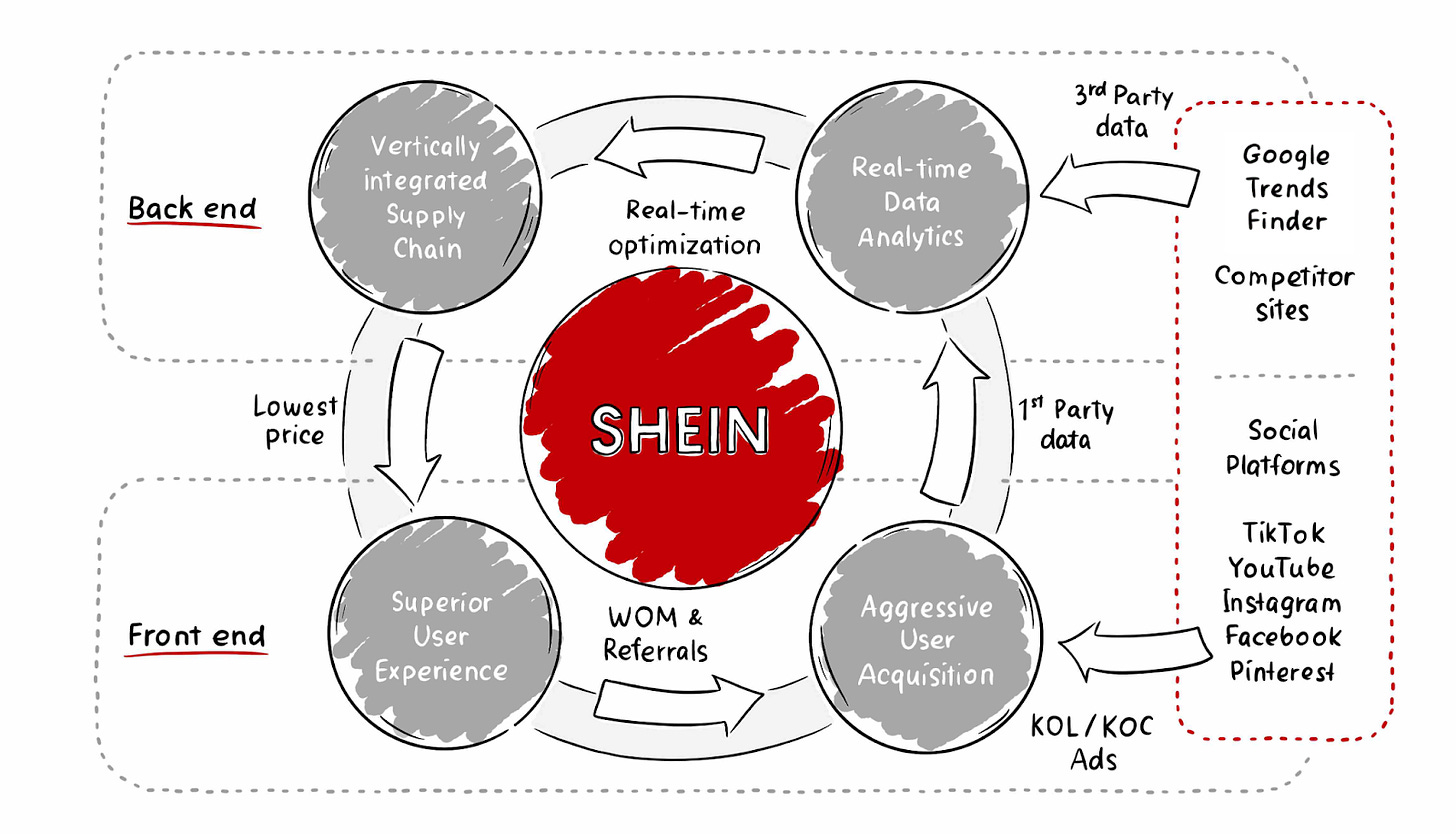

Shein’s Secret Sauce

What’s the secret to Shein’s success? Why does it sell cross-border but not domestically?

Shein’s strength comes from taking China’s advantages, and applying them to the global market.

Everyone knows that China is good at manufacturing. That’s been true for decades. What’s changed is that over the past five years, Chinese companies have caught up, and in some cases surpassed, the rest of the world in its understanding of mobile ecommerce consumer experience.

That’s Shein’s story in a nutshell.

Its advantage starts with the product it sells -- clothing. Chinese companies are particularly well-suited to compete in this category thanks to their tight links with local manufacturing, which create quality products, quickly, at low prices, on a huge scale. What’s normal to a Chinese consumer is outlandishly cheap to a western one.

It extends into how it sells -- largely through its app, powered by a world-class back-end and a scaled modern marketing engine.

In the US a lot of ecommerce still happens in the browser. In China, ecommerce is heavily weighted towards native mobile apps. Accordingly American ecommerce sellers will often prioritize resources on their website over the app, while in China almost every transaction happens in some kind of mobile app. “Chinese have no habit of buying from an official website!” laughed two Shenzhen based VCs recently on their podcast, ridiculing Ikea’s China ecommerce strategy. That would seem to give the advantage in selling into the US to those companies who are able to tap into people experienced in web-based ecommerce.

BUT, the demographic that Shein targets is the young mobile obsessed Gen-Z, whose habits are much closer to those of the average Chinese, both groups skipped the Web 1.0, Web 2.0 eras. America’s Gen-Z was also the first to catch on to China's short video trend, picking up the TikTok habit long before millennials caught on. Shein has been able to do something very difficult and expensive for any brand: it’s been able to push even western shoppers to use its app instead of its website, moving the battle onto ground where the Chinese hold an advantage — native mobile app ecommerce. The numbers back it up: Shein has a much higher percentage of app traffic than any of its American competitors. (Reddit user poll)

In China, there is a huge pool of talent and industry knowledge built up around mobile app ecommerce. By simply adapting China industry best practices to the ROW, Shein is able to give itself a massive advantage with which companies like Fashion Nova, H&M, and Zara can’t compete.

This situation holds parallels to TikTok which was able to take very standard China playbook UGC platform practices (e.g. directly paying creators) and apply them to Western markets.

Selling fast-fashion through an app allows Shein to lean into its advantages to compete on three vectors it’s uniquely suited to win:

Price: “affordability”

Selection: “choice”

Retention: “addictiveness”

Shein’s ability to deliver on those three pillars are based on its advantages on the back-end (affordability and choice), front-end (addictiveness), and in the connection between the two.

To win, it treats atoms like bits, and builds a system that connects supply and demand, in real-time.

In Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, Richard Rummelt writes that any good strategy needs to have Coherent Actions, a set of interconnected things that a company does to carry out the guiding policy, each reinforcing the other to build a chain-link system that is nearly impossible to replicate. That’s exactly what Shein has built.

This is Shein’s Real-Time Retail Flywheel. It feels crazy to make the comparison, but Shein combines parts of Apple and Amazon to build its compounding advantage. Like Apple, it controls its entire value chain, from the factory floor to the Shein app. Building a strong brand and user experience should allow it to charge premium prices, like Apple, but instead, it chooses to consistently delight customers through lower prices, like Amazon. It’s an incredibly difficult flywheel to pull off, but Shein is, and it’s hard to imagine any other company competing with it now that the flywheel is spinning.

So how does it work? Let’s start with the back-end.

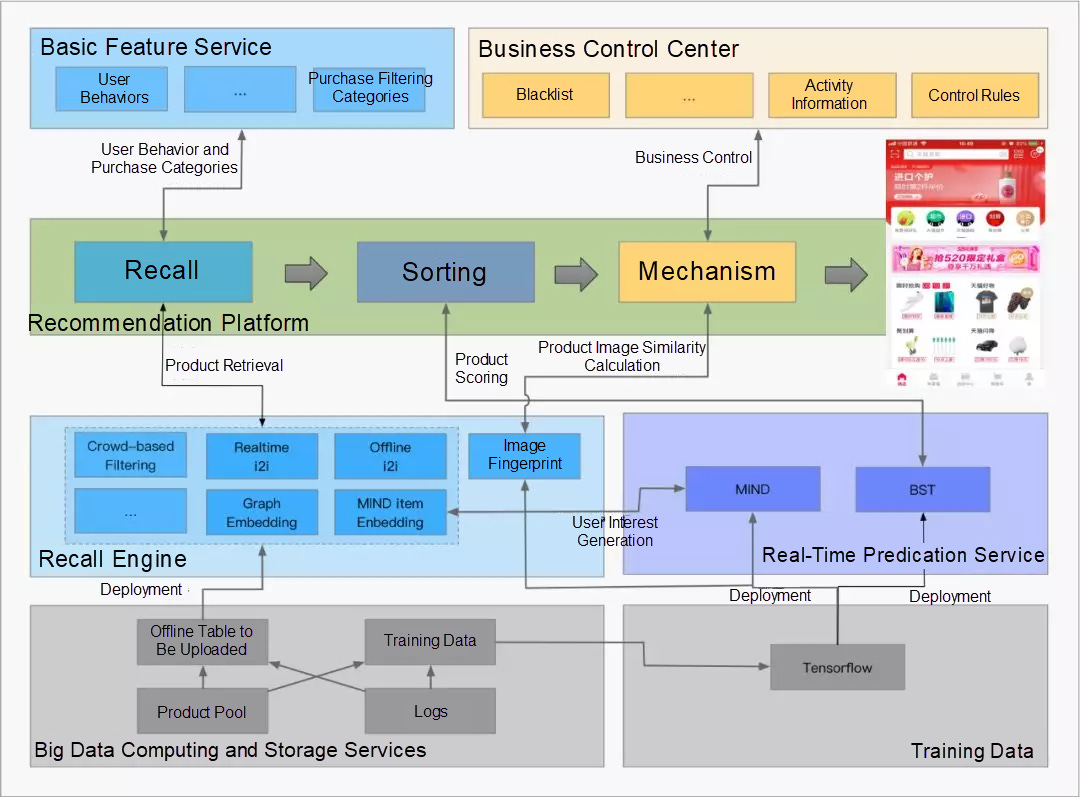

It starts with algorithmically scouring the internet and Shein’s own data to pull out fashion trends. As one of Google’s largest China-based customers, Shein has access to Google’s Trend Finder product, which allows for real-time granular tracking of clothing related search terms across various countries. This allowed Shein, for example, to accurately predict the popularity of lace in America during the summer of 2018. Combine that with Shein’s huge volume of 1st party data through its app from around the globe and software-human teams that scour competitors’ sites, and Shein understands what clothes consumers want now better than anyone with the possible exception of Amazon.

Shein feeds that data to its massive in-house design and prototyping team who can get a product from drawing board to production and live-online in as little as three-days. Because Shein is located in the heart of Guangzhou, China’s fashion manufacturing capital, and has built up years of loyalty with its suppliers, it’s able to operate as if it does all of its own manufacturing. For one, that means it can start with incredibly small batches, around as small as 10 items, and then adjust up from there. Once a product is live, Shein creates more 1st party data, which it uses to automatically adjust production on the fly. It’s doing this with tens of thousands of new SKUs every day.

How the hell does it pull that off?

Shein built a magic system to make that possible at scale by directly connecting the factory floor to the consumer without the need for human intervention. Remember that Shein’s suppliers have to use its software? Through it, they receive updates on new orders instantly based on consumer behavior, and send back real-time inventory and capacity data. One executive at a competitor told Tegus that, “Every area of their website is tied to the ERP (enterprise resource planning) system and their manufacturing. So they are live updating their manufacturing capability based on who’s looking at what on the website and who’s buying what.”

Imagine that a new item, designed based on Shein’s own and 3rd party data, goes live on the website, and immediately starts getting user behaviors correlated to sales (i.e. X number browsing product details, X number added to shopping cart). Based on taps, clicks, and sales, an algorithm doubles the production quota, which is immediately updated on the factory floor with extra materials automatically ordered. A second algorithm updates the weightings and recommends the item to more users with similar profiles. That’s impossibly fast to compete with.

None of this is easy. Connecting all of these systems, both internally and with third-parties, means that Shein needs world-class engineering and machine learning talent. Skimming through Shein’s China recruitment site reveals they are hiring for hundreds of technical positions including big data developers, and AI algorithm engineers.

Like TikTok, Shein replaces local knowledge with AI. In TikTok and the Sorting Hat, Eugene Wei wrote, “It turns out that in some categories, a machine learning algorithm significantly responsive and accurate can pierce the veil of cultural ignorance. Today, sometimes culture can be abstracted.” Shein is proof of that statement’s truth beyond short-form video.

Saudi Arabia is one of Shein’s biggest markets. How much real cultural insight and nuance do you think Shein’s team in Guangzhou have about Saudi Arabian women? Probably not much more than you or me reading this now. But the point is, they don’t need to.

Shein relies predominantly on data and algorithms, supplemented by human insight. It’s a bit like GPT-3 for fashion. It’s hard to see how a successful American DTC ultra-fast fashion brand with a human-driven design point-of-view like Fashion Nova scales beyond serving its core target. It’s easy to see how Shein with neutral middle of the road branding could expand to serve any man, woman, child or er… dog (PetsIn) in any geography.

All of this -- the demand prediction, fast iteration, small batches, and manufacturing relationships -- mean that Shein eliminates waste and is able to deliver low prices on quality, trendy items. Shein can outmatch other Chinese manufacturers on price, but to compete in the cross-border market, it doesn’t have to. That’s why Shein sells everywhere but China. Prices that seem normal to Chinese consumers used to Alibaba’s Taobao or Pinduoduo, seem laughably cheap to European, American, and Middle Eastern customers. Going direct in China is a more difficult proposition. Realistically getting to scale online in apparel means working through Alibaba, which breaks the direct connection to the consumer.

The ability to manufacture quality, trend-responsive clothing quickly and sell it at low prices feeds into the front-end of the business, where Shein’s user experience kicks in to create addictiveness.

Building an addictive fashion mobile ecommerce experience comes down to four things:

Low prices

Great pictures

Lots and lots of reviews, with pictures and video

Using every trick in the book to build frequency of use

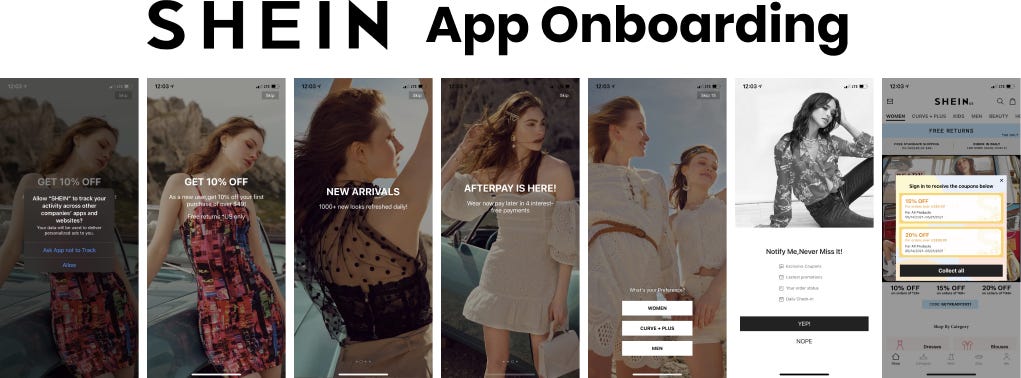

The first time you open the Shein app, after asking you whether it can track your activity in other apps and websites (lol, never hurts to ask!), it walks you through a multi-screen flow:

Screenshots of Shein app onboarding (iOS, May 2021)

10% off and free returns on your first order to encourage shopping quickly without worrying about what happens if the product isn’t good,

Highlights the value prop of 1,000+ new items per day to encourage you to come back

Announces Afterpay to remove even more friction from buying

Asks which category you want to shop to better personalize the experience

Prompts you to turn on notifications, to encourage repeat usage and build the addiction

Offers 15-20% off when you sign in within a week, to get you to create an account

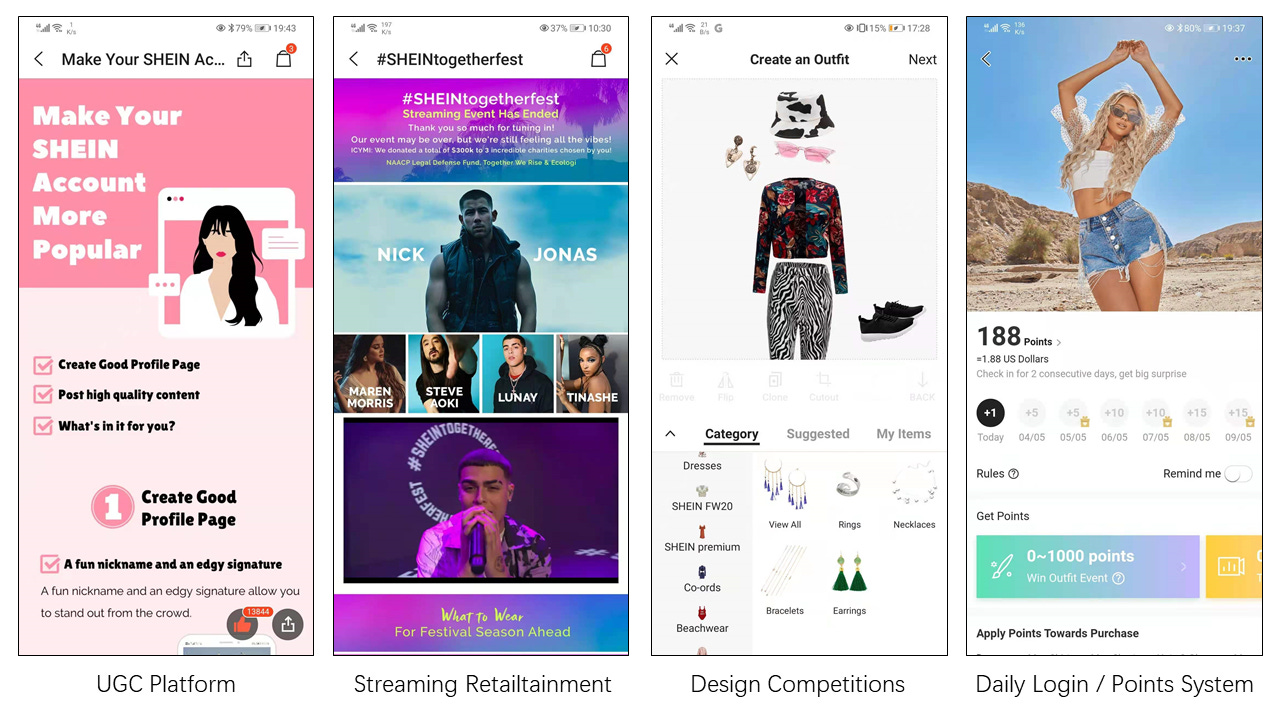

Once you’re in, Shein does a bunch more things to get you hooked:

Screenshots of features within the Shein app (Android, May 2021)

Generous points system: earn rewards for daily log ins, design games, verifying email, and more. Matthew verified his email, left a few reviews, and already has almost $3 in points.

Incentivised Reviews: Reviews are particularly important in fashion ecommerce as a way to reduce expensive return rates. Star ratings don’t tell you much. Pictures tell you a lot. Guess what Shein incentivises with points—pictures with the user’s size information. This allows shoppers to more accurately judge if something will fit them.

User-Generated Content (UGC): Inspired by Little Red Book and Taobao, Shein encourages UGC. Users can gain followers to their profile and be showcased in the app modelling the clothes they buy, building loyalty to the brand, providing more pictures for other users to judge suitability of items, and creating a content feed that keeps users hooked.

Livestream Events & Retailtainment: Like a mini Alibaba 11.11 event, Shein has #SHEINtogetherfest featuring influencers like Nick Jonas, Mareen Morris, Steve Aoki, and Hailey Beiber.

Recommendations: The Shein app experience is more one of a discovery driven recommendation feed rather than a primarily search driven experience. China’s mobile ecommerce is an environment where recommendation traffic far outweighs search driven traffic. Heavy reliance on recommendation over search is a common thread that runs through the world of Chinese mobile internet. Accordingly, there’s a huge pool of expertise built up around ecommerce recommendation, as showcased in this paper.

Given Xu’s background in SEO, it’s not surprising that he built a strong and cutting edge marketing funnel. With low prices and a user experience optimized for conversion and retention, Shein is able to pour money and attention into the top of the funnel.

Shein has been early to each of the big ecommerce customer acquisition channels, and it hasn’t shied away from paid. As mentioned above, it’s one of Google’s biggest China-based clients, it sells products through Amazon, and spends aggressively on Facebook and Instagram. (Puja told Packy that she sees Shein ads all the time on Instagram.) It was also very early on Pinterest, which has a heavily-female user base and was actually the company’s biggest acquisition channel in 2013-2014.

But the key to Shein’s success has been influencers and UGC. This is where Shein’s flywheel looks even more impressive. Because Shein’s prices are so low, users can afford to buy a ton of items, which they highlight in “hauls” videos, like the one below from YouTube:

TikTok is another massive channel. “TikTok and Shein is the perfect marriage because Shein offers an attainable price, and it is much more fun to watch people trying on their ‘haul’ than it is to scroll through pictures of people wearing clothes on Instagram or long videos on YouTube,” Mae Karwowski, chief executive of Obviously, an influencer agency, told the Telegraph.

Rui Ma pointed out to me that “What’s also happened in recent years is that the advanced nature of chinese digital marketing means that there’s a lot of strategic know-how already for these teams. They know how to do TikTok campaigns well because of Douyin.” An April Jing Daily article said that on TikTok alone, the #shein hashtag has generated 6.2 billion views, and that the brand appears in over 70 other hashtags.

Much of the content is posted for free by users hoping to take advantage of high affiliate fees; they can earn 10-20% of sales, which is unheard of. That generates a ton of content, the best of which Shein pays to promote, across all of its channels. In China, these micro-influencers are called KOC, or Key Opinion Consumers.

The company also leans heavily into KOL, or Key Opinion Leaders, celebrities paid to endorse the company. According to Jing Daily, Katy Perry, Lil Nas X, Rita Ora, Hailey Bieber, and Yara Shahidi have all represented Shein over the past year. TikTok’s biggest star, Addison Rae, also promotes the company across her channels:

Shein’s marketing engine is working, as evidenced by its insane revenue growth, but also its low customer acquisition costs (CAC). LatePost pointed out that an early Shein competitor, Choies, fell behind because it had to spend 25-30% of revenue to acquire customers, whereas Shein spent 15-20%, giving the company the ability to generate higher profit margins.

Strong demand restarts the flywheel: more users mean more data and more volume, which means smarter decisions and lower prices, which lead to a better user experience, higher retention, and the ability to continue to spend aggressively on acquiring customers. The profit margin, along with the hundreds of millions of VC dollars, means more money to invest in hiring engineers and machine learning experts to strengthen the machine, which means better predictions, more choice, lower prices, and more addictiveness.

TikTok wasn’t the first short-form video company, but it took it to another level, and created a flywheel in which more users led to better data which led to better recommendations which led to more users and more engagement. Now, it seems as if it’s uncatchable.

Similarly, Shein was not the first ultra-fast fashion company, but now that the flywheel is spinning so tightly, it’s hard to imagine that any fast-fashion will be able to catch Shein. In fact, Shein’s biggest threat may be itself.

Criticism and Controversy

Shein has built an awe-inspiring ecommerce machine, but we would be remiss to avoid acknowledging the company’s critics. In many ways, the company seems to have borrowed Facebook’s “Move Fast and Break Things” mantra and applied it to the world of atoms. That has inevitably led to some big mistakes.

Shein has faced controversy, some applicable to the entire fashion industry, and some specific and deserved.

In July 2020, for example, Shein created a controversy when they sold Muslim prayer mats as fun home decor. Just four days later, they got in even more trouble for selling a “Metal Swastika Pendant Necklace.”

When they were called out, Shein posted to Instagram that:

The Buddhist symbol has stood for spirituality and good fortune for more than a thousand years, and has a different design than the Nazi swastika which stands for hate. But frankly, that doesn't matter because we should've been more considerate of the symbol's hurtful connotations to so many people around the world and we didn't.

In the most generous interpretation, the incident at least highlights the difficulty selling to a global audience without a local presence and understanding.

Security has been an issue, too. In September 2018, a massive data breach exposed 6.42 million customers’ confidential information. Somehow, this didn’t become a big story in western media, but if Shein gets the attention of US politicians, you’d have to imagine that data security (combined with that request to track all activity across other apps and websites), will be a source of concern.

Other criticisms of the company are more broadly applicable to the fashion industry and Chinese manufacturers.

Take the environmental impact. While there’s some confusion around the real impact of fashion on the environment, this 2020 Nature article on the environmental impact of fast-fashion concludes that, “Ultimately, the long-term stability of the fashion industry relies on the total abandonment of the fast-fashion model, linked to a decline in overproduction and overconsumption, and a corresponding decrease in material throughput.” That’s not mincing words. Shein, which is faster and cheaper than traditional fast fashion, likely has a correspondingly negative impact on the environment.

Shein has also been subject to claims that it uses child labor, which are unsubstantiated and difficult to take seriously. It uses a sophisticated supply chain, and Guangzhou, where it’s manufacturing is located, has one of the highest GDPs in China.

There are claims that are more likely true. One, that it makes poor-quality, flimsy clothes is both true and false depending on the piece in question. Another, that it sold fakes during its early years, is believable, as it was buying directly from wholesale markets and focused more on SEO than product quality. Alibaba, too, faced heavy criticism and pressure from partner brands about the sale of fakes on its platform.

Thus far, though, Shein has been able to respond to and shake off criticism. It keeps growing and expanding, and it’s just getting started.

The Big Picture

There will be a point in the future -- maybe in a decade, maybe in fifty years -- when commerce is truly instant. Think of a thing, get that thing. That’s the logical endpoint. Shein will be well-positioned when we get there.

Before that sci-fi future, while consumers are still buying online and having things made and shipped to them, the logical interim conclusion is manufacturers going direct on a global scale, cutting out all of the middlemen, and replacing local know-how with algorithms.

It’s hard to imagine a company better-positioned for retail’s near-term future than Shein.

Shein’s success is not built upon unfair government subsidies or stolen American IP—the company sells bikini bottoms, not AI chips. Just like TikTok, Shein’s achievements in America are based upon serving the needs of young Americans better than American companies.

Chinese companies can now manufacture products, write code, and market to global consumers as well as anyone in the world. “Made in China” now means more than just cheap products, it means leading global brands. Very few companies do it better than Shein.

How will American companies respond? The current ultra-fast fashion leaders are probably too late. Sellers who rely on Amazon for sales know they are essentially renting a counter in a huge mall where the landlord’s primary business is selling advertising space to your competitors directly next to all of your products. Oh, and the landlord can kick you out anytime. Many of the biggest Amazon China based 3P sellers were taken down a few days ago, a move that sent shockwaves through China’s cross-border ecommerce industry.

Thanks in part to Shein, manufacturers now have more power than they ever had. When you cut out the middlemen, whoever’s left on both sides share the spoils. Thus far, the lion’s share of the spoils are going to Shein; might giving more of a cut to manufacturers be a vector of attack?

Italic is a startup dark horse. It’s also applying the cross-border C2M model to the US market, but is focusing on the basics, which don’t require the same turnover or speed as Shein’s clothing. It has a pristine brand and a profitable membership model. No doubt inspired by Shein, it’s also innovating on supplier relationships by letting manufacturers keep more of the profit in exchange for taking more inventory risk. Ultimately, it’s building software and distribution that any high-quality manufacturer can plug into to build a business selling abroad. Will Italic be Shopify to Shein’s Amazon, arming the rebel manufacturers for whom on-time payments are now table stakes?

What’s certain is that Shein will have to continue to evolve, adapt, and expand. 100% YoY growth gets harder to achieve every year, and success invites competition. Chinese Mini-Sheins like Zaful and StyleWe are coming out of the woodwork, and there will be more, each sucking in data, learning from the previous generation, and iterating faster and faster, like a meta-Shein for Sheins.

Shein has a few potential areas for improvement and expansion:

From 1p to 1p + 3p: Shein will need to become a platform that leverages its manufacturing, software, and demand-generation know-how to sell an ever-expanding selection of products while maintaining quality. Shein X, which works with outside designers and handles everything post-design, is a step in that direction.

Acquisition: After partially causing its demise, Shein recently attempted to purchase the UK’s TopShop. There will be further consolidation in the space as Shein proves out the advantage of speed, data, and scale.

Logistics: Despite design and manufacturing speed, it still takes a long time for Shein products to arrive. To make the experience truly instant, it will need to improve here.

Category Expansion: Shein reportedly invested in Outer, an outdoor furniture company, in its January 2021 Sequoia China-led Series A. Is that a sign of the company’s desire to expand beyond clothing, and even beyond high-frequency purchases? There’s still low-hanging fruit in other categories that behave more similarly to fast-fashion.

Whichever direction it chooses, a more immediate question may be when Shein will go public. If you believe the rumors in China, it’s planning an IPO later this year, but that rumor predates the recent market turbulence. Given the secrecy around the company, we can’t wait to get our hands on the S-1 whenever it comes.

We lied earlier, when we said there were only three pictures of Chris Xu online. There are four. For a company so good at controlling its online presence, it may be telling that one of those four is this one:

It shows Xu, standing arms-crossed and happy, in New York’s Financial District, in front of the Wall Street Bull. As if we needed another reason to be bullish on Shein.

How did you like the Not Boring x Matthew Brennan collab?

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday,

Packy

That's one heck of an analysis. Super stuff.

Awesome analysis, but I just wanted to pointed out that “that request to track all activity across other apps and websites” will probably not be a source of concern, as it will gradually be requested by most apps due to Apple’s recent privacy updates (App Tracking Transparency).