Many Small Steps for Robots, One Giant Leap for Mankind

A Co-Written Essay with Evan Beard

Welcome to the 1,179 newly Not Boring people who have joined us our last essay! Join 256,826 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday! I am thrilled to bring you not boring world’s first co-written essay (cossay? need something here) with my friend Evan Beard, the co-founder and CEO of Standard Bots.

Evan is the perfect person to kick this off.

I have known Evan for ~20 years, which is crazy. We went to Duke together, worked at the one legitimate startup on campus together (which still exists!), and even won a Lehman Brothers Case Competition together (which won us the opportunity to interview at the investment bank right before it went under).

After school, Evan went right into tech. He was in an early YC cohort, back when those were small. He started a company with Ashton Kutcher. I was interested in tech from the outside and always loved talking to Evan, so we’d catch up at reunions and then go our separate ways. In September 2023, a mutual acquaintance emailed me saying “there’s a company you should have on your radar, Standard Bots,” and I looked it up, and lo and behold, it was founded by Evan Beard!

Since reconnecting, Evan has become one of a small handful of people I ask dumb robot questions to. He’s testified in front of Congress on robotics. Last year he spoke at Nvidia’s GTC on the main stage. He was even featured doing robotic data collection in A24’s movie Babygirl alongside Nicole Kidman! Evan knows robots.

And the questions are very dumb! Robotics as a category has scared me. As valuations have soared, I’ve mostly avoided writing about or investing in robots, because I haven’t felt confident enough that I know what I’m talking about to take a stand.

Which is the whole point of these co-written essays!

Evan has dedicated his career to a specific belief about how to build a robotics company. He’s making a different bet than the more hyped companies in the space1, one that is like a Russian Doll with a supermodel in the middle - not very sexy on the outside but sexier and sexier the more layers you remove until you get to the center and you’re like, “damn.”

So throw on a little Robot Rock…

And let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Framer

Framer gives designers superpowers.

Framer is the design-first, no-code website builder that lets anyone ship a production-ready site in minutes. Whether you’re starting with a template or a blank canvas, Framer gives you total creative control with no coding required. Add animations, localize with one click, and collaborate in real-time with your whole team. You can even A/B test and track clicks with built-in analytics.

Framer is making the first month of cossays free so you can see what we’re all about. Say thanks to Framer by building yourself a little online world without hiring a developer.

Launch for free at Framer dot com. Use code NOTBORING for a free month on Framer Pro.

Many Small Steps for Robot, One Giant Leap for Mankind

A Co-Written Essay With Evan Beard

There is a belief in my industry that the value in robotics will be unlocked in giant leaps.

Meaning: robots are not useful today, but throw enough GPUs, models, data, and PhDs at the problem, and you’ll cross some threshold on the other side of which you will meet robots that can walk into any room and do whatever they’re told.

In terms of both dollars and IQ points, this is the predominant view. I call it the Giant Leap view.

The Giant Leap view is sexy. It holds the promise of a totally unbounded market – labor today is a ~$25 trillion market, constrained by the cost and unreliability of humans; if robots become cheap, general, and autonomous, the argument goes that you get Jevons Paradox for labor - available to whichever team of geniuses in a garage produces the big breakthrough first. This is the type of innovation that Silicon Valley loves. Brilliant minds love opportunities where success is just a brilliant idea away.

The progress made by people who hold these beliefs has been exciting to watch. Online, you can find videos of robots walking, backflipping, dancing, unpacking groceries, cooking, folding laundry, doing dishes. This is Jetsons stuff. Robotic victory appears, at last, to be a short extension of the trend lines away. On the other side lies fortune, strength, and abundance.

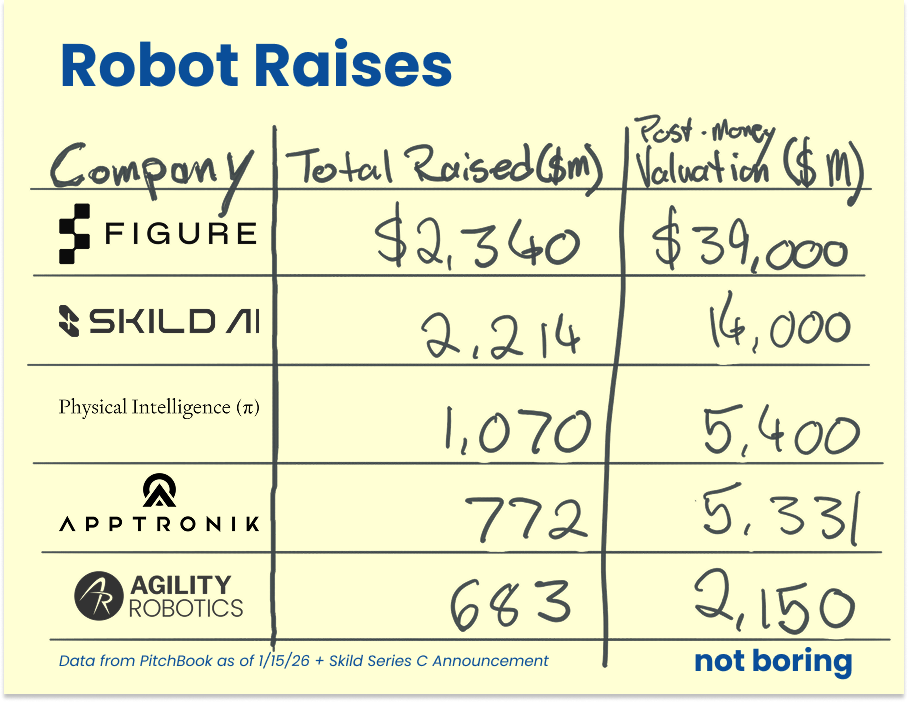

As a result, companies building within this view, whether they’re making models or full robots, have raised the majority of the billions of dollars in venture funding that have gone towards robotics in the past few years. That does not include the cash that Tesla has invested from its own balance sheet into its humanoid, Optimus.

To be clear, the progress they’ve made is real. VLAs (vision-language-action models), diffusion policies, cross-embodiment learning, sim-to-real transfer. All of these advancements have meaningfully expanded what robots can do in controlled settings. In robotics labs around the world, robots are folding clothes, making coffee, doing the dishes, and so much more. Anyone pretending otherwise is either not paying attention or not serious.

It’s only once you start deploying robots outside of the lab that something else becomes obvious: robotics progress is not gated by a single breakthrough. There is no single fundamental innovation that will suddenly automate the world.

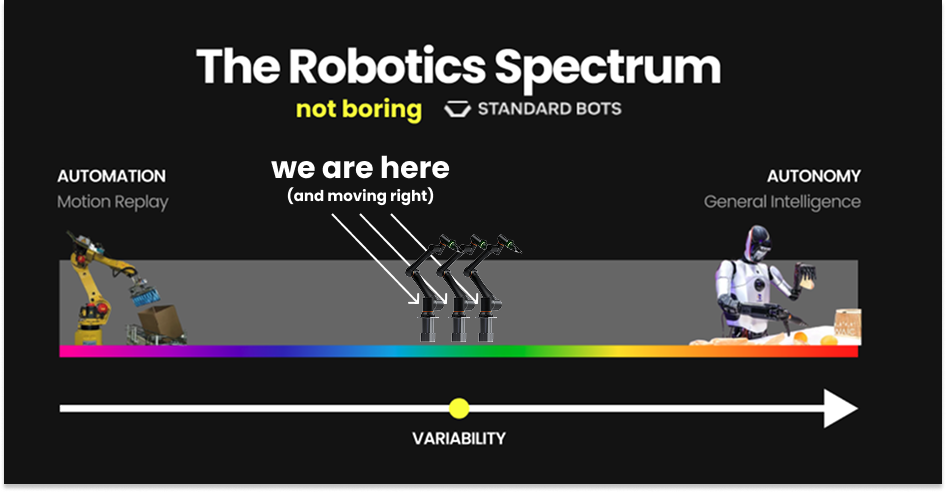

We will eventually automate the world. But my thesis is that progress will happen by climbing the gradient of variability.

Variability is the range of tasks, environments, and edge cases a robot must handle. Aerospace and self-driving use Operational Design Domain (ODD) to formally specify the conditions under which a system can operate. Expanding the ODD is how autonomy matures. It’s even more complex for robotics.

Robotic variables include what you’re handling (identical vs. thousands of different SKUs), where you’re working (climate-controlled warehouse with perfect lighting vs. a construction site with dust, uneven terrain, weather, and changing layouts), how complex a task is (single repetitive motion vs. multi-step assembly requiring tool changes), who’s around (operating in a caged-off cell vs. collaborating alongside workers in shared space), how clear the instructions are (executing pre-programmed routines vs. interpreting natural language commands like “clean this up” or “help me with this”), and what happens when things go wrong (stopping when something goes wrong vs. detecting errors, diagnosing causes, and autonomously recovering).

Multiply these variables together and the range can be immense2. This is because the spectrum of real, human jobs is extremely complex. A quick litmus test is that a single human can’t just do every human job.

Most real jobs are not fully repetitive, but they’re also not fully open-ended. They have structure, constraints, and inevitable variation, much to the chagrin of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Henry Ford, and leagues of industrialists since. Different parts, slightly bent boxes, inconsistent lighting, worn fixtures, humans nearby doing unpredictable things.

It’s the same for robots.

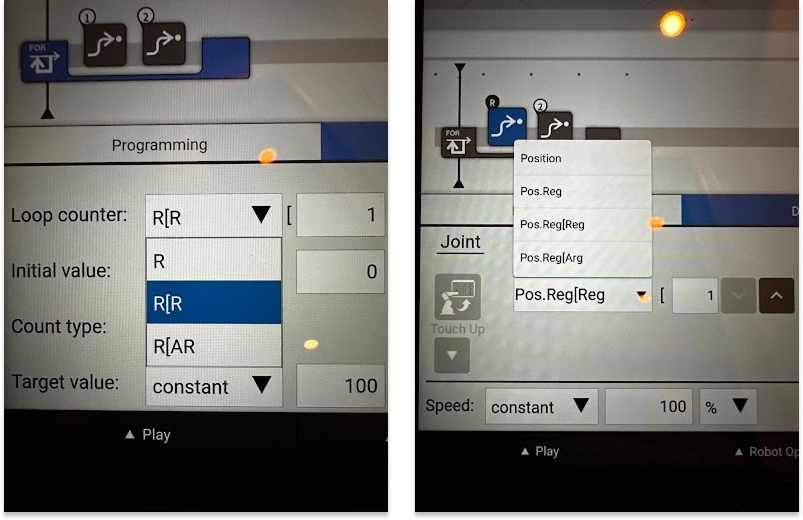

At one end, you have motion replay. The robot moves from Point A to Point B the same way, every time. No intelligence required. This is how the vast majority of industrial robots work today. You save a position, then another, then another, and the robot traces that path forever. It’s like “record Macro” in Excel. It works beautifully as long as nothing ever changes.

At the other extreme, you have something like a McDonald’s worker. Different station every three minutes. Burger, then fries, then register, then cleaning. Totally different tasks, unpredictable sequences, human interaction, chaotic environment. The dream of general physical intelligence is a robot that can walk into this environment and just... work.

At one extreme is automation. At the other is autonomy. Between those extremes lies almost all economically valuable work.

Between automation and a McDonald’s robot that can fully replace a worker is an incredible number of jobs.

It’s my belief that these small steps across this spectrum are where we’ll unlock major economic value today.

That’s what my company Standard Bots is betting on.

Standard Bots makes AI-native, vertically integrated robots. We’re currently focused on customers within manufacturing and logistics. We’ve built a full stack solution for customers to train robot AI models, from data collection, review, and annotation, to model training and deployment. And we make these tools accessible enough for the average manufacturing worker to use.

In a market full of moonshots, our strategy might look conservative. Even tens of millions of dollars in revenue is nothing compared to the ultimate, multi-trillion dollar, abundance-inducing prize that lies in the future.

It isn’t.

We are building a real business today because we believe that it’s the most likely to get us to that abundance-inducing end state first.

Two Strategies: Giant Leap or Small Step

If you believe there’s a massive set of economically valuable tasks waiting on the far side of some threshold, then the optimal strategy is to straight-shot it. Lock your team in the lab. Scale models. Scale compute. Don’t get distracted by deployments that might slow you down. Leap.

If you believe, like we do, that there is a continuous spectrum of economically valuable jobs, many of which robots can do today, then the best thing to do is to get your robots in the field early and get to work.

Each deployment teaches you where you are on the gradient. Success shows you what’s stable, failure shows you where the model breaks, and both tell you exactly what to work on fixing next. You iterate. You take small steps.

It’s widely accepted in leading LLM labs that data is king. The optimal data strategy is to climb this spectrum one use case at a time. You don’t need “more” data. What you really want is diversity3, on-policyness4, and curriculum5. Climbing the spectrum iteratively is the strategy that best optimizes for these three dimensions of good data for any given capital budget. Real deployments on your bots get you on-policyness (nothing else can), the market intelligently curates a curriculum, and both provide rich and economically relevant diversity.

We’ve learned this lesson over years of deployments.

Whenever robotics evolves to incorporate another aspect of the job spectrum between automation and autonomy, it also unlocks another set of jobs, another set of customers, another chunk of the market. One small step at a time.

Take screwdriving. It is much easier to use end-to-end AI to find a screw or bolt than to try to put everything just so in a preplanned and fixed position. Search and feedback is cheap for learning systems. Our robot can move the screwdriver around until it feels that it’s in the right place. It wiggles the screwdriver a little. It feels when it drops into the slot. If it slips, it adjusts. And when our robots figure out how to drive a screw, it unlocks a host of jobs that involve screwdriving. Then we start doing those and learn the specifics of each of them, too.

We learn on the job and get better with time. Many of these robots are imperfect, but they’re still useful. There’s no magic threshold you have to cross before robots become useful.

That’s not our hypothesis. It’s what the market is telling us.

Industrial robotics is already a large, proven market. FANUC, the world’s leading manufacturer of robotic arms, does on the order of $6 billion in annual revenue. ABB’s robotics division did another $2.4 billion in 2024. Universal Robots, which was acquired by Teradyne in 2015, generates hundreds of millions per year.

These systems work, even though they work in very narrow ways. Companies spend weeks integrating them. Teams hire specialists to program brittle motion sequences. When a task changes, those same specialists come back to reprogram the whole thing, for a fee. The robots repeat the same motions endlessly, and they only work as long as the environment stays exactly the same.

Despite all of that friction, customers keep buying these robots! That’s the market talking. Even limited, inflexible automation creates enough value that entire industries have grown around it. The low-variability left side of the spectrum already supports billions of dollars of business.

In machine learning, progress rarely comes from a single leap. It comes from gradient ascent: making small, consistent improvements guided by feedback from the environment.

That’s how we think about robotics too.

Our plan is not to leap from lab demonstrations to generally intelligent robots. Instead, our plan is to climb the gradient of real-world variability and capture more of the spectrum.

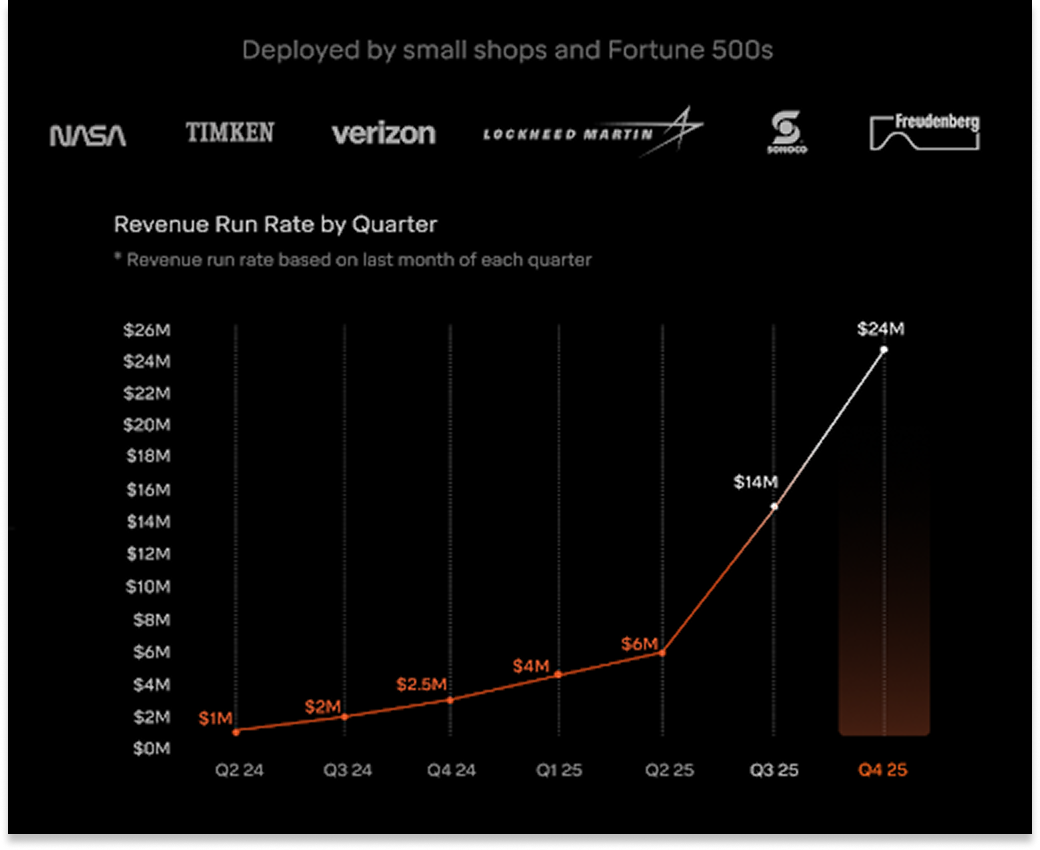

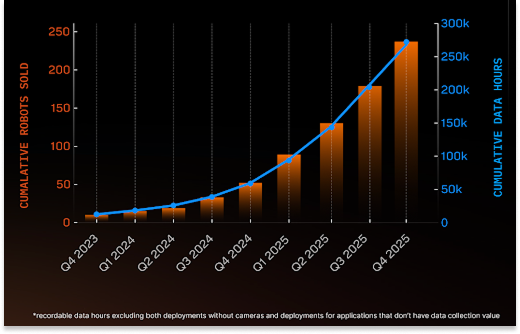

It’s working so far. We have 300+ robots deployed at customers including NASA, Lockheed Martin, and Verizon. We ended the year on a $24 million revenue run rate, with hundreds of millions of dollars in customer LOIs and qualified sales pipeline. The kink you see in this curve is due to the fact that our robots keep getting better and easier to use the more they (and we) learn.

Customers are happy because we’re already meaningfully easier to deploy and cheaper to adapt than classical automation, and while we don’t have generally intelligent AI models that can automate any task, we can already automate jobs with a level of variability that no other robotics company can.

We expect our robots to do everything one day, too. We just believe that:

“Everything” is made up of a continuous spectrum of small “somethings.”

Each of those “somethings,” whether it’s packing a bent cardboard box or checking a cow’s temperature through its anus (a real use case), requires use-case-specific data to be done well.

By deploying our robots in the field today, we get paid to collect the data we need to improve our models. That includes the most valuable data of all: intervention data when a robot fails.

When we find a new edge case, we can iterate on our entire system of variable robots. This is because we are fully vertically integrated, including data collection, the models, the firmware, and the physical arm.

Our plan is to get paid to eat the spectrum. In the process, we plan to collect data no one else can. We’ll then use this data, which is tailor made for our robots, to iterate on the whole system quickly enough to get to general economic usefulness before the giant leap, straight-shot approaches do.

There’s a lot of context behind our bet. The first and most important thing you need to understand is that robotics is bottlenecked on data.

Robotics is Bottlenecked on Data

Robots already work very well autonomously wherever we have a lot of good data. For example, cutting and replanting pieces of plants to clone them as seen in the video below.

This is unintuitive, because it’s almost the opposite challenge Large Language Models (LLMs) seem to face. What the average AI user like you and I experiences is that the models improve and LLMs automatically know more things.

But LLMs had it relatively easy. The entire internet existed as a pre-built training corpus. There is so much more information on the internet than you could ever imagine. Any question you might ask an LLM, the internet has probably asked and answered. The hard part was building architectures that could learn from it all.

Robotics has the opposite problem.

The architectures largely exist. We’ve seen real breakthroughs in robot learning over the last few years as key ideas from large language models get applied to physical systems. For example, Toyota Research Institute’s Diffusion Policy shows that treating robot control policies as generative models can dramatically improve how quickly robots learn dexterous manipulation skills. The magic of this approach is that it took the architecture largely used to generate images, in which the model learns to remove noise in an iterative manner like in the GIF below…

…and instead applied it to generate the path of the robot’s gripper. An idea that works in one domain is applied to another and BOOM — the outcome works pretty well.

The advancements that have ushered in this new era are small ones adding up. For example, take what researchers call “action chunking,” in which the model predicts a sequence of points to move through in the future instead of just one. That helps performance and smoothness a lot.

Vision-language-action models such as RT-2 combine web-scale semantic understanding with robotic data to translate high-level instructions into physical actions. Systems like ALOHA Unleashed demonstrate that transformer-based imitation learning can enable real robots to handle complex, multi-stage tasks — including tying shoelaces and sorting objects — by watching demonstrations. And emerging diffusion-based foundation models like RDT-1B show that training on large, diverse robotic datasets enables zero-shot generalization and few-shot learning across embodiments.

But those papers also all found something similar. For those remarkable innovations to happen with any reasonable success rate, you need data on your specific robot, doing your specific task, in your specific environment.

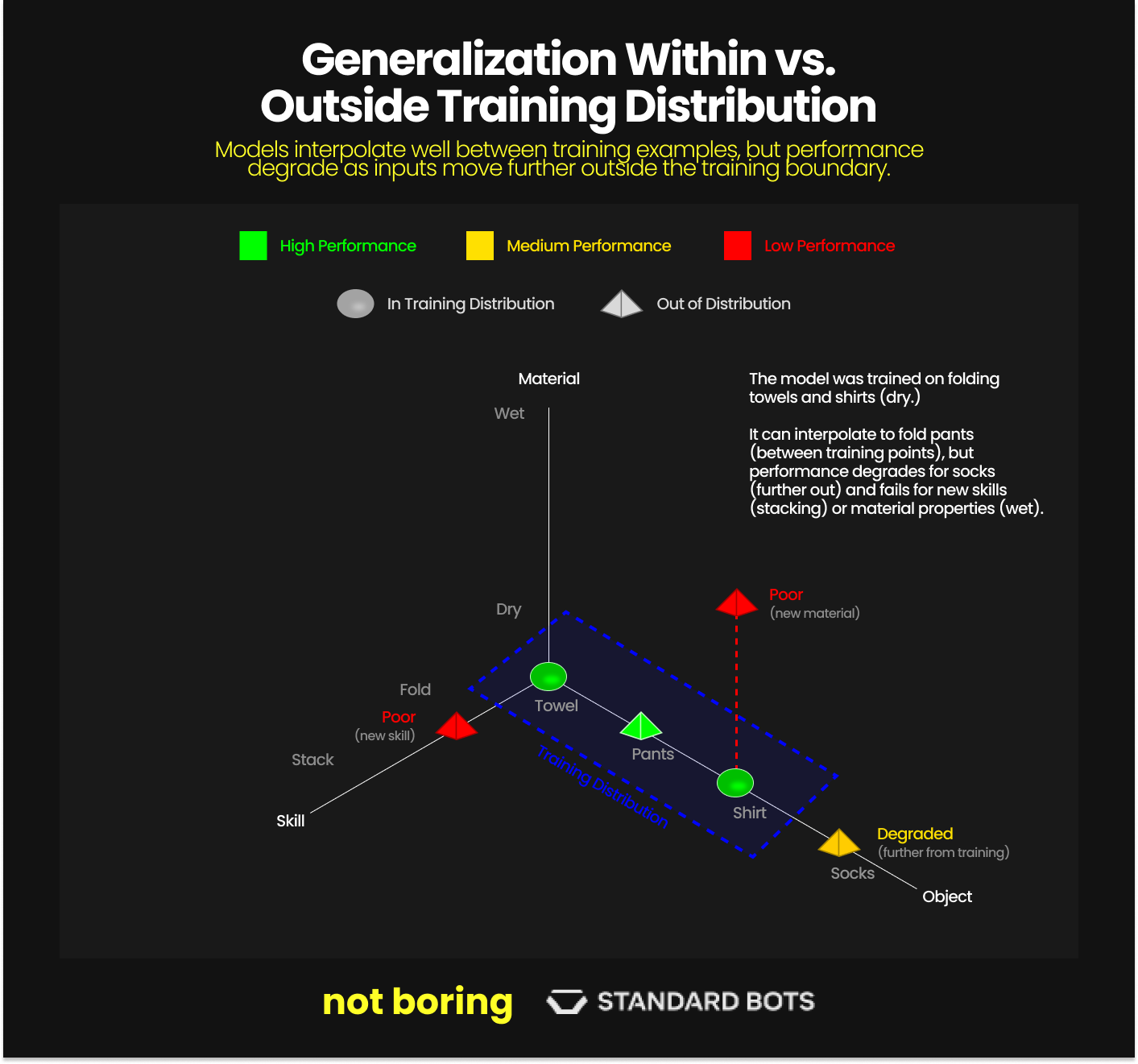

If you train a robot to fold shirts and then ask it to fold a shirt, it works. Put the shirts in different environments, on different tables, in different lighting. It still works. The model has learned to generalize within the distribution of “shirt folding.” But then try asking it to hang a jacket or stack towels or to do anything meaningfully different from shirt folding. It fails. It’s not dumb. It’s just never seen someone do those things.

Robots can interpolate within their training distribution. They struggle outside of it. This is true for LLMs, too. It’s just that their training data sets are so large that there isn’t much out of distribution anymore.

This is unlikely to be solved with more compute or better algorithms. It’s a fundamental characteristic of how these models work. They need examples of the thing you want them to do.

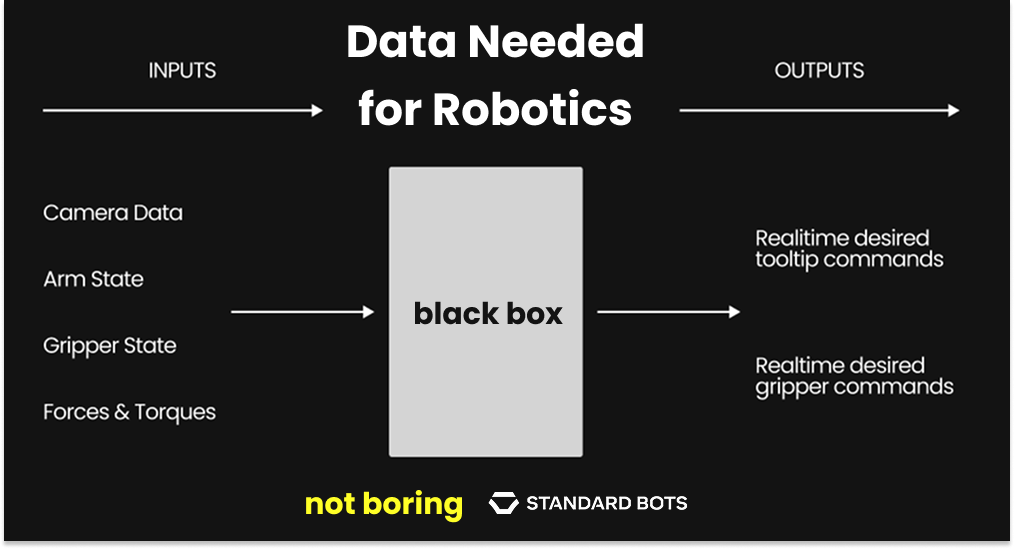

So how do you collect example data?

One answer would be to create it in the lab. Come up with all of the edge cases you can think of and throw them at your robots. As John Carmack warned, however, “reality has a surprising amount of detail.” The real world chuckles at your researchers’ edge cases and sends even edgier ones.

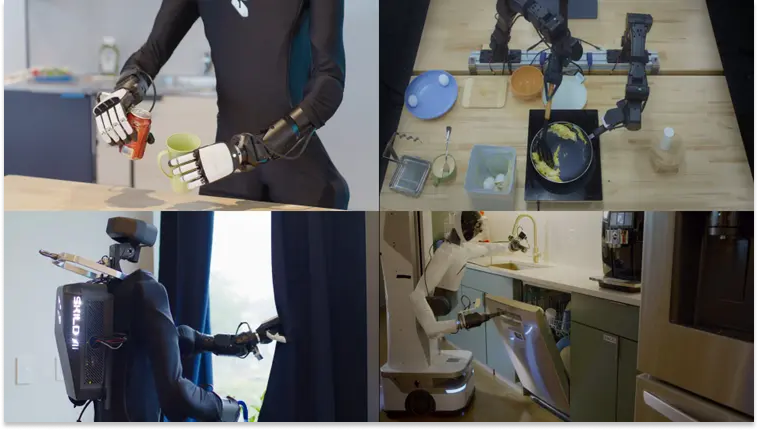

Another answer would be to just film videos of people doing all of the things that you’d want the robots to do. Research has shown signs of life here.

For example, Skild has shown that a robot can learn how to do several common household tasks from video and only a single hour of robot data per task.

This is exciting progress, and on the back of it, just this week, Skild announced a $1.4 billion Softbank-led Series C at a valuation of over $14 billion.

Ultimately, general video may lift the starting capabilities of a model. But it still doesn’t remove the need for the on-robot data for the final policy, even for simple household pick-and-place tasks (and industrial tasks will need much more data). For one thing, robots need data in 3D, including torques and forces, and the data needs to occur through time. They almost need to feel the movements. Videos don’t have this data and text certainly doesn’t.

It’s kind of like how reading lots of books makes it easier to write a good book, but watching lots of golf videos doesn’t do much for actually playing golf.

If I want to learn to golf, I need to actually get out there and use a body to swing clubs. Similarly,

the best way to collect data is by using hardware. And for that, there are a number of different collection methods: leader-follower arms, handheld devices with sensors on them, gloves and wearables, VR and teleoperation, and direct manipulation, as in, literally moving the arm and grabbing an object.

All of these approaches can work. Each has pluses and minuses. We use a mix of many of them.

But let’s continue with the golf analogy. Practicing with any human body is better than watching videos, but practicing with my body is the best. That’s the body I’m actually going to play with.

In the same way, even data from other robots isn’t as valuable as data from your own hardware. If your data and your hardware aren’t aligned, you need 100x or 1,000x more data. If I wanted to work on my robot, but I didn’t have my robot, I could use a similar robot to observe the activity. But for it to be effective, I’d need a lot of similar robots.

This is one of the many challenges for general robotics models.

What the Giant Leap Actually Requires

The most obvious counterargument to everything I’ve argued so far and everything I will argue throughout is that while the Giant Leap models haven’t unlocked real world usefulness yet, they undoubtedly will as the labs continue to make breakthroughs. It’s not fun to be short magic!

For the amount of money invested in the space, though, there’s surprisingly little good public thinking about what the Giant Leap approach actually entails.

What is the bet or set of bets they’re making, and how should we reason about them?

The approach we’re taking at Standard Bots is hard. It’s often slow and frustrating. And from the outside, there’s a huge risk that we do all of this work and then, one day, we wake up and one of the big labs has just… cracked it. But I feel confident in our approach because I don’t think the Giant Leap views will produce meaningful breakthroughs, and I want to explain why.

For sure, you’ll continue to see increasingly magical pitches on robot Twitter:

“We can train on YouTube videos. No robot data needed!”

“We can generate the missing data in simulation!”

“We’re building a world model. Zero-shot robotics is inevitable!”

And some of these are even directionally right. There is real, actual progress behind a lot of the buzz. But there’s a ton of noise, too.

Again, I am biased here. But I’m also putting my time and money behind that bias. So here’s how I think about what’s actually going on — what Google, Physical Intelligence (Pi or π) and Skild are actually up to in the labs in pursuit of a genuine leap — from (don’t say it, don’t say it) first principles.

A Model Takes Its First Steps

A lot of the modern robotics-AI wave started the same way: pretrain perception, learn actions from scratch. Meaning, teach the robot how to perceive and let it learn by perceiving.

Take Toyota Research Institute’s Diffusion Policy. The vision encoder (the part that turns pixels into something the model can use) is pretrained on internet-scale images, but the action model begins basically empty.

Starting “empty” is… not ideal, because the model doesn’t yet have what researchers call perception–action grounding. It hasn’t learned the tight relationship between what it sees and what it does:

“Moving left” in camera space should mean moving left in the real world.

A two-finger gripper can clamp a cup by the handle or rim, but not by poking the center like a toddler trying to eat soup with a fork.

Contact is physics, not simple geometry. The world changes when you interact with it.

This grounding stage is basically the toddler phase: I see the world, I flail at the world, sometimes I succeed, mostly I bonk myself.

But most serious teams can collect enough robot data to establish basic grounding in days. So far, so good.

How to Train a Robot

Say you want to train a robot to do a task. Here is what you need to do:

1. Get data

2. Train model

3. Eval and continuous improvement

Get data: You can teleoperate in the lab, the real world, simulation, or learn from internet or generated videos. Each option has its own tradeoffs, and robotics companies spend a lot of time thinking about and experimenting with these tradeoffs.

Train model: Are you going to build it from scratch or rely on a pre-trained model to bootstrap? Training from scratch is easier if you are building a smallish model. Large models typically have entire training recipes and pipelines that involve pre-training, mid-training and post-training phases. Pre-training teaches the robot the basics about how the world works (general physics, motion, lighting). Post-training is about giving tasks specific superpowers.

In LLM terms, pre-training teaches a model how words are related in the training distribution. It learns their latent representations. Post-training (instructGPT, RLHF, Codex) gets a model ready for deployment use cases like chat agents or coding. Post-training can also make the robot faster, cheaper, and more accurate by tightening up the trajectories with RL. A lot of the RL buzz you hear about in the LLM world actually began with robotic task-specific policies.

All sounds great, but you still need the data. The big question is: how do you get the data?

Video Dreams (and Their Limits)

Giant leapers have two big salvation pitches for how they’ll get the data they need.

The first is existing whole-internet video.

Models clearly learn something from video: object permanence, rough geometry, latent physical structure, the ability to hallucinate the backsides of objects they’ve never seen (which is either very cool or deeply unsettling, depending on your relationship with reality).

So why not slurp YouTube, learn the world, and then just... do robotics?

Think about this first. What can humans learn from watching a video? And what can’t they?

Videos are useful for many things:

Trajectories and sequencing: Video is great at showing the arc of motion and the order of steps in an action.

Affordances and goals: You watch someone turn a knob and you learn that knobs want to be turned. Switches want to be pressed.

Timing and rhythm: Timing matters for things like locomotion, assembly, or anything that’s basically choreography. Video carries timing.

If you’re learning to grasp, video can show you: reach → descend → close fingers → lift.

And it can show tool use: the tilt of a cup, the swing of a hammer, the way people “cheat” by sliding things instead of lifting them.

But there are whole categories of data that video simply doesn’t carry: mass, force, compliance, friction, stiffness, contact dynamics.

Humans can sometimes infer some of this visually, but only because we’re leaning on a lifetime of embodied experience. Robots don’t have that prior.

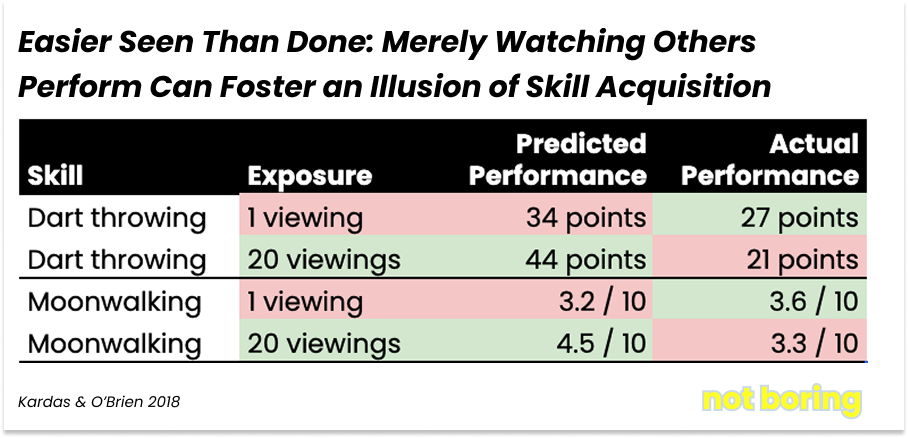

In experiments with over 2,200 participants, researchers Michael Kardas and Ed O’Brien examined what happened when people watched instructional videos to learn physical skills like moonwalking, juggling, and dart throwing. The results were striking:

As people watched more videos, their confidence climbed sharply. Meanwhile, their actual performance barely moved, or even got worse.

That’s the embodiment gap. Video tells you what to do, but not what it feels like to do it. You can watch someone moonwalk all day. You still won’t feel how the floor grips your shoe, how much pressure transfers to your toes, how to modulate tension without faceplanting.

And robots have it worse than humans. At least we have priors. Robots have sensors and math.

I’m going to get a little spicy here.

If you’re not paying very close attention, it looks like feeding robots internet videos is working.

Watch Skild’s “learning by watching” demos closely. Only the simplest tasks use “one hour of human data.” More impressive demos are nestled in the middle of the video without that label. And the videos aren’t random ones pulled from YouTube either. They’re carefully collected first-person recordings from head-mounted cameras. Is doing all of this that much easier than just using the robots?

In short, there are three big reasons video isn’t enough:

Coverage: internet video doesn’t cover the weird, constrained, adversarial reality of industrial environments.

Data efficiency: learning from video alone typically takes orders of magnitude more data than learning from robot-collected data, because the mapping from pixels to action is underconstrained without embodied sensing.

Missing forces: two surfaces can look identical and behave completely differently. Video can’t disambiguate friction. The robot finds out the fun way.

Then, you still have the translation problem: human hands aren’t robot grippers, kinematics differ, scale differs, compliance differs, systematic error shows up unless you train with the exact end effector you’ll deploy.

Which is why many of these companies end up quietly going back to teleoperation.

Human video is useful for pretraining. But weakly grounded data has a real cost: you can either do the hard work of actually climbing the hill, or you can wander sideways for a long time and call it progress.

OK, so the videos on YouTube aren’t that useful. What about simulation?

Where World Models Do and Don’t Work

Simulation and RL are the other big salvation pitch. If robots can self play in a simulated environment that mimics real world physics, the trained policy should transfer to real robots in the real world. And to be fair: sim is really good at certain things right now, especially rigid-body dynamics.

NVIDIA has pushed this hard for locomotion. Disney’s work (featured in Jensen’s GTC 2025 keynote) shows the magic you get when you combine good physics with good control: humanoids that walk, flip, recover (beautifully) in a simulator.

That success comes down to two ingredients:

The physics is tractable: Simulators can handle rigid bodies + contacts + gravity well. You can randomize terrain, generate obstacles, and train robust walking policies without touching the real world.

The objective is specifiable: RL needs a reward.

For walking, the rewards are straightforward: distance traveled, stability, energy use, speed.

For animation, it’s even cleaner: match a reference motion without falling.

So locomotion is the happy place because three things line up for machine learning. You can model the physics, measure the goals, and reset for free when things go wrong.

Then, people try to extrapolate from walking → factory work, and everything breaks.

When you do real things in the real world, physics gets messy. Real tasks involve soft materials, deformed packaging, fluids, cable routing, wear-dependent friction, tight tolerances, and contact-dominated outcomes.

You can simulate parts of this, but doing it broadly and accurately becomes a massive hand-crafted effort. And you still won’t match the edge cases you see in production. Again, you might as well do the real thing.

With real tasks, rewards get brittle or unwritable. “Make a sandwich” is not scalar. Even “place this part down” is full of constraints: don’t tear, don’t spill, align, recover if it slips, don’t jam, don’t scratch the finish, don’t do the thing that worked in sim but breaks the machine in real life.

Waymo is a great example. Waymo uses a ton of simulation today, but real-world data collection from humans driving cars came long before the world model. Do you remember how long human Google workers drove those silly looking cars around collecting data before Waymo ever took its first autonomous ride? As the company wrote in a recent blog post, “There is simply no substitute for this volume of real-world fully autonomous experience — no amount of simulation, manually driven data collection, or operations with a test driver can replicate the spectrum of situations and reactions the Waymo Driver encounters when it’s fully in charge.”

You need to collect that data in the real world, and then you can replay and amplify it in sim. That’s how you get the last few “nines.”

Also, resets. What it takes to start over.

In sim, resets are free. In reality, resets take work. Walking is the rare exception because the reset is “stand back up,” but if you want a robot to learn sandwich making through trial and error, someone has to: clean up, restock, reset, try again, and repeat forever, slowly losing their will to live. Cleaning up after a half-baked bot is not why you signed up to be a robotics researcher.

So simulation is valuable, but it’s still not a replacement for real data collection. The highest-leverage use of sim is after deployment: when real robots surface real failure modes, and sim is used to reproduce and multiply those rare cases.

Which brings us back to first principles.

So What’s the Best Way to Train a Robot? (Like You’d Train a Human)

Think about how you train a human.

For simple tasks, text works. For slightly harder ones, a checklist helps. But most real factory work isn’t that simple. You need alignment, timing, judgment, recovery, and the ability to handle “that thing that happens sometimes.”

At that point, demonstration wins. It’s the most information-dense way to transfer intent. This is why people in the trades become apprentices.

It’s the same for robots. And it’s okay if a robot takes minutes or even hours to learn a task, as long as the learning signal is high quality.

Training time doesn’t need to be zero.

Which leads to what we’ve been saying: the giant leap isn’t, and can’t be, architectural.

The Giant Leap, the point at which the model has suddenly seen enough and can do anything, isn’t real. It is enticing and sexy (maybe in part it’s enticing and sexy because it’s always just out of reach). But it doesn’t exist. Even the smartest humans need training and direction. Terence Tao would need years to become an expert welder.

We think the answer is simply committing to taking the time to collect the right data. Robot-specific, task-specific, high-fidelity data, even if it means fewer flashy internet demos.

Three things follow from this:

You will always need robot-specific data.

The highest-quality way to convey a task is to show it (teleop or direct manipulation).

Once you have strong domain-specific data, low-quality vision data from unrelated tasks doesn’t help much.

LLMs feel magical because they interpolate across the full distribution of human text. Robots don’t have that luxury.

To be clear, my contention is not that video, simulation, and better models aren’t useful. They clearly are. My contention is that with them, you still need to collect the right data.

In order to do a specific job — say, truck loading and unloading, or biological sample preparation, or cow temperature checking — you need data on that specific job, and it’s best if that data is generated on your own hardware.

And in order to do any job, which is the promise of general physical intelligence, you need to be able to do a lot of specific jobs, which means that you’ll still need data on each of those specific jobs, or at least jobs that look so similar that you can reliably generalize.

The upshot is that while it may be possible to build generally capable robots with all of this data, all of this data is wayyyy harder to collect than people realize, and it is also way harder to generalize outside of the data you do have (in fact, it’s not yet proven possible).

Which creates a chicken & egg problem:

You can’t really test a use case without the data (and a specific type of data)

You can’t get the data in a high-fidelity way without doing the use case

That’s the main reason that we think robotics progresses in small steps, not giant leaps. You need to collect all of the data in either case!

And if you believe that, then the next move is obvious…

Get Paid to Collect Data

So how do you gather that data? Do you make thousands of robots — robotic arms, in our case — and build sets where they can practice?

If you think that robots need to get past a certain threshold of capability to be economically useful, that might be the best approach. But we’ve already disproved that thesis. FANUC, ABB, Universal Robots, and others generate billions in revenue for basic automation.

Customers are used to old robots that require a ton of expensive implementation work and are brutal to program. We realized that we could compete with them and win.

We make better arms and automate for a wider range of use cases than current deterministic software. And we do it for less money.

When we deploy a robot for a new customer, it takes a few easy steps and a few hours. And it’s getting easier and easier. We get paid for hardware and software upfront. Our gross profit covers our acquisition costs within 60 days.

This all means that we’re able to scale our data collection efforts almost as fast as we can make the robots, and it’s all funded by our customers. We’re happy for obvious reasons. They’re happy for obvious reasons. And the plan is that our robots keep learning in the field and we both keep getting happier.

Crucially, when there’s an issue, we teleoperate into the environment, error correct, and most importantly, learn from the issue. (Oh, and we have exclusive rights to the issued patent for using AR headsets to collect training data for robot AI models).

This is the secret sauce.

Earlier this week, a16z American Dynamism investor Oliver Hsu wrote an essay on the very real challenges that occur when going from the lab to the real world.

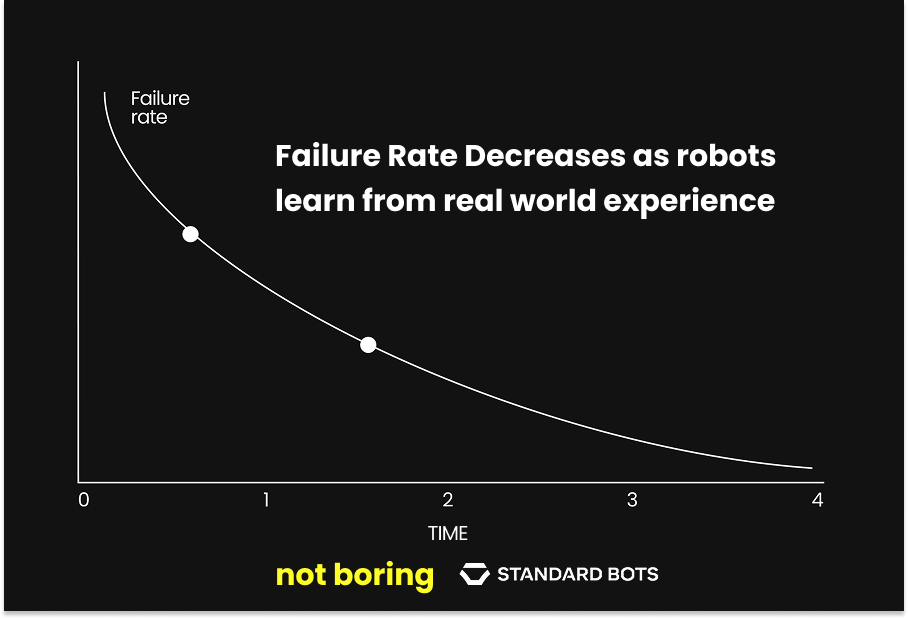

In papers and in the lab, a robot that succeeds 95% of the time sounds amazing. In a factory running a task 1,000 times a day, that means 50 failures per day. That’s I Love Lucy on the chocolate line performance. Even 98% means 20 stoppages a day. 99% means 10. You would fire any employee who messed up that much in a week.

According to Oliver, production environments require something closer to 99.9% reliability — one intervention per day, or even every few days — which is the difference between having to hire someone to fix your robot’s mistakes and just letting it work.

He’s right. 95% just isn’t good enough… unless you approach the problem like we do and improve over time. In which case, 95% is a great place to start!

95% is plenty good enough for Day 1 if you’re ready to teleoperate in and fix the 5% issues, which we do. We can ship robots to do things that deterministic, automated robots can’t. It allows us to continue to eat the spectrum by taking on use cases that we can mostly handle, and to treat human interventions as both a service and a data collection mechanism. The robot handles what it can, humans step in at hard cases, and those corrections flow back into training.

This has worked incredibly well. By learning from each of the real-world challenges that make up that 5%, we can bring failure down imperceptibly close to 0% within weeks of deployment.

That’s because intervention data at the moment of failure is the best data. We’ve learned that collecting data right around where the thing failed allows us to efficiently pick up all of the edge cases, and this is often the minimum training data we need. We concentrate at the boundary where autonomy breaks instead of just collecting data on the 95% of stuff we do flawlessly over and over again, and we learn where reality actually disagrees with our model. And because our robots are the ones generating the failures — not humans — we learn where our robots fail.

Learning where robots fail is important. There’s a mismatch when you train a robot on human demonstrations: the human operates in their own state distribution, but the robot will drift into states the human never showed it. Better to let the robot fail and act quickly to resolve.

With every customer, we learn about a use case, train our models, get ongoing data, learn as they fail, and improve our models.

At a certain point, a given use case is largely solved. We have eaten that piece of the spectrum. We can move on to the next, handle a little more variability.

So far, it seems that each use case we solve, along with the resultant improvements we make to our software, firmware, hardware, and models, makes it easier to eat adjacent pieces of the spectrum.

One common misconception about our approach is that it implies starting from scratch with every use case. That’s not how it works. Remember the screwdriver.

We don’t think of our system as a collection of isolated task-specific models. We think of it as a shared foundation of physical skills — perception, grasping, force control, sequencing, etc. — that compounds across deployments. For each new use case, we post-train on top of an ever-improving foundation.

With each use case that gets solved, those foundational capabilities get better. That makes adjacent tasks easier. Over time, the same core skills (screwdriving, for example) show up repeatedly in different combinations and those shared skills compound.

Ideally, the whole thing spins faster and faster. And it’s starting to seem like this is what will happen.

This is how the Standard Bots machine works. We get paid to learn. We get better, faster because we are forced to interact with reality.

And customers teach us about use cases that we never would have guessed existed.

A Forced Aside on Cow Temperatures

I was telling Packy (and he made me include this) about one of our new salespeople’s first days. He’d received a lead from a farm that wanted to use our robots to take their cows’ temperatures. Unusual temperature is the earliest, cheapest signal that something is wrong with a cow.

Do you know how to take a cow’s temperature?

What you do is, you take a thermometer and you stick it in the cow’s anus. You do this once a week, once a month, or somewhere in between, depending on the stage of the cow’s life. There are 90 million cows in the United States. Based on the cycle time math (it takes about one minute per cow) that’s a thousand-robot opportunity.

Two things about that opportunity:

If you’d said, “Evan, if your life depended on it, give me a job that you could automate in the dairy industry,” I would have said milking cows. I’d never think of automating sticking a thermometer in a cow’s anus. That’s a job you learn about from customers.

This is not a job for a humanoid. Surprisingly few jobs are, when you think about it.

One reason it’s not a job for a humanoid is that a humanoid would be overkill. You’re paying for general capabilities (and legs) when what you need is one thing done over and over and over (in a stationary position). Another reason is that a humanoid would be underkill for that specific job: it wouldn’t be set up, neither physically nor in the model, for the specific job.

What you’d need is a flexible gripper, for one thing. But really, it all comes down to entry speed. You can’t just jam it in. The cows don’t like that. And how do you figure out the right entry speed? Every cow is different. Turns out, you need a camera trained on the cow’s face and a model trained on hundreds of cows’ facial reactions; the cow’s face tells you when to slow down (and this behavior should emerge automatically during end-to-end training without any hand-crafted prior). The model needs to be able to understand what to do with that specific sensor data instantly in order to tweak the arm’s speed and angle of attack quickly enough for the cow to let it in. And so on and so forth.

Another reason it’s not a job for a humanoid is that they’re going to be pretty expensive. Elon himself predicted that by 2040, there will be 10 billion humanoids, and they’ll cost $20-25,000 each. About half that cost comes from the legs, which are probably a liability on the farm. Lots of shit in which to slip.

Here’s one more huge reason it’s not a job for a humanoid. Humanoids don’t exist today.

Other than some toy demonstrations, humanoids just do not exist in the field today. Generally intelligent robots certainly do not exist in the field today.

Sidebox: What about humanoids? (defining here as legged bipeds)

The promise of humanoids is captivating to many investors (especially Parkway Venture Capital). Understandably so. “The world was created for the human API.” It sounds so nice, and it’s true to some extent.

But that dream collides uncomfortably with reality. As I was recently quoted saying in the WSJ Tesla Optimus Story: “With a humanoid, if you cut the power, it’s inherently unstable so it can fall on someone.” And “for a factory, a warehouse or agriculture, legs are often inferior to wheels.”

I’m incentivized to say that, so don’t take it from me. In the same story, the author writes that, “inside the company [Tesla], some manufacturing engineers said they questioned whether Optimus would actually be useful in factories. While the bot proved capable at monotonous tasks like sorting objects, the former engineers said they thought most factory jobs are better off being done by robots with shapes designed for the specific task.” (That’s what we do with our modular design, by the way. Thanks, Tesla engineers.)

The Tesla engineers aren’t alone. People who run factories and care more about their business than demos don’t see the ROI, which is why you see companies like Figure shifting their focus to the home. This is the dream. Robots in the home is Rosie. But to put a robot in your home, with your kids, they need to be really reliable.

For humanoids to really be useful in the home, we’d like to coin the HomeAlone Eval.

The humanoid needs to survive in a house with a team of feisty eight-year-olds trying to trip, flip, and slip it — all without injuring them. It’s even hard for a human to remain stable when your kids jump on your back going up the stairs. And if you fall on them, at least you’re soft and fleshy. Robot, not so much. This humanoid eval is much harder to train with RL, but we’ll need to see that before we have one in our house.6

There are interesting approaches to the home that align with our thesis. Matic and now Neo are getting paid to learn inside of your house, from different angles. Matic is starting with a simple and valuable use case - vacuuming and mopping - learning the home, and working up from there. Neo is teleoperating its robots while it collects data.

But autonomous humanoids do not, in any practical sense, exist.

We can wait for humanoids to exist. Or we can be out here learning from customers about all of the things that robots might be able to do as we chew off more and more variability, and then getting paid to learn and perfect those use cases. All while our one-day competitors are stuck in the lab.

We are running as fast as we can with that headstart. A big reason we’re able to run so fast is that we’re vertically integrated.

Why Vertically Integrate?

There is a big reason that deployment accelerates learning that has nothing to do with models and everything to do with hardware.

Recall that data is 100-1,000x more efficient when aligned with its hardware. The more of the hardware you control, the more true this statement is.

Most labs use cheap Chinese arms from companies like Unitree. This makes short-term sense. Those arms have gotten really good and they’re very cheap, a couple thousand bucks.

At Standard Bots, we’re betting on vertical integration.

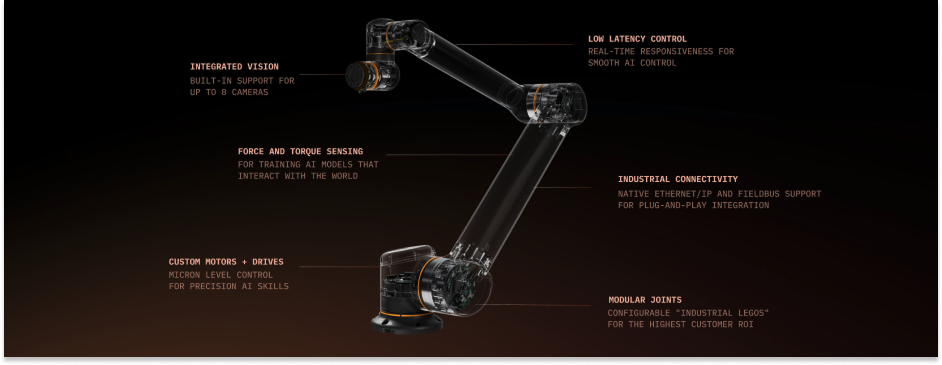

We make an industrial grade arm that’s designed for end-to-end AI control. In particular, torque sensing in the joints. Because when you’re doing AI, you want to be able to record how you interact with the world, and then be able to train the model on that interaction in order to have the model recreate it.

Which is why we care about torque sensing and torque actuation: so the motor can precisely control how hard the joint pushes, and so the robot can feel how the environment pushes back through the joint. If you don’t have that, then you’re kind of stuck with AI for pick and place or folding.

We’ve created a unique way to do the torque sensing. Everyone else does strain gauges and current-based torque sensing. We have a method to directly measure torque through the bending of the metal, and our way is more accurate and more repairable, easier to manufacture, just better all around. Really, really great torque sensing.

To do that, we make practically everything ourselves. We even make our own motor controller to commutate the motor. The things we don’t make are bearings and chips. Everything else, for the most part, is going to be made by us. So that’s really deep vertical integration.

It’s necessary, though. Old robots don’t work with new models.

Old robots were designed for motion replay: you send a robot a 30-second trajectory and the robot executes it. AI requires 100Hz real-time control. You’re sending a new command 100 times-per-second based on what the model sees in real-time. A lot of the existing robot APIs don’t even have real-time torque control. I can tell my robot to go somewhere, but I’m just giving it a position. If it hits something, it’s going to hit it at max force. It doesn’t have the precise control I need for it to do a good job.

This doesn’t work for a robot that thinks for itself in real time. So we wrote our own firmware for real time torque control with motor commutation at 60 kHz (60,000 times per second).

This firmware makes our robots smoother, more precise, and more responsive, and also easier and more fun to use. This is really important because it means that we can physically handle a lot more use cases. This, in turn, means that hardware won’t limit our ability to eat more of the spectrum.

Between putting these arms that can physically handle a lot of use cases out in the field and our own data collection for pre-training — a handheld device7, our actual arms8, and increasingly, AR/VR9 — we’re vertically integrated on the data side, too.

This data feeds our pre-training mix. Think of it as the first industrial foundation model for robotics pre-training. More vertical integration. As discussed, this model can be smaller, add core skills over time, and can be deployed with post training on a specific task.

A mix of hundreds of factories, which are our customers. Payloads up to 66 pounds, not this three-pound bullshit. Industrial environments, industrial equipment. An industrial-grade arm that’s IP-rated and made for 24/7 operation, paired with an industrial-grade model.

Of course, we’re thinking about everything a person could do in a factory warehouse and putting that into our pre-training mix, just like everyone else. The difference is, our robots then quickly go out and learn everything a person actually does in a factory.

This is a fundamental bet we’re making.

Some companies are betting that they can just go create some model, around which an ecosystem will develop, and they’ll then bring their product to market.

We think that the market is too nascent for that.

The tight integration between hardware, data, and model is so crucial while we are still learning how to do new use cases that we believe vertical integration is the only way to do it right.

This is how new technology markets develop. In Packy’s Vertical Integrators, Part II, Carter Williams, who worked at Boeing in Phantom Works, explained that the need for vertical versus horizontal innovation moves in cycles. “Markets go vertical to innovate product, horizontal to reduce cost and scale. Back and forth over a 40-50 year cycle.”

In robotics, we are still very much in the “innovate product” phase of the cycle.

One day, once we’ve collected data on use cases that represent the majority of the value in the industrial economy (and beyond), the industry will probably modularize to reduce cost and scale. Hopefully, we won’t have to make everything ourselves for the rest of time. We still have to today.

The other thing about vertical integration is that controlling everything helps us adapt fast. Every day, we learn something new about how customers operate, what their needs are, how different types of factories run. The ability to learn something, fix, and adjust is invaluable.

For example, we realized in the field that models actually have to understand the state of external equipment, not just the thing the robot is working on. Often there’s an operator that’s using a foot pedal at a machine. We need to collect data on the foot pedal — like whether it is pressed or released — and the model needs to be able to understand these states. From there, we need to make a generic interface that works for all types of external equipment.

And there’s the other thing we’ve discussed as crucial to our business: it’s really important to be able to collect data on failure. So we have a whole loop on that too.

That’s it. That’s the plan.

Robotics is bottlenecked on data. We get paid to collect data by building better robotic arms for industrial use cases. These use cases are broader and larger than we anticipated. For each one, we deploy, learn, find edge cases, intervene, collect the data, and improve. This is necessary at the model level for a specific task, and it’s also necessary at the level of the system. And the only way we are able to do this quickly (or at all) is because we are vertically integrated.

Rinse, robot, repeat.

This is how we eat the spectrum, one small step at a time.

Small Steps, Small Models, Big Value

In The Final Offshoring, Jacob Rintamaki’s excellent recent paper on robotics, he writes, “one framing of general-purpose robotics that I haven’t seen much of isn’t that we now have a robot that can do anything, but rather we have a robot which can quickly, cheaply, and easily be made to do one thing very well.”

That is our plan. To do one thing very well, for every industrial case, one thing at a time. Eventually, we will reach across the spectrum of use cases.

“The strategy for these companies then,” Rintamaki continues, “given that reducing payback time may be All You Need, is to deploy into large enterprise customers as aggressively as possible to start building moats that their larger video/world-model focused competitors still find difficult to match.”

Yes.

Here, I want to reintroduce the concept of variability to discuss the nature of our moats.

There is the data moat that I’ve written about at length here. We are getting paid to collect the exact data we need to make our specific robots better.

What we do with that data, for the particular slice of variability that makes up each use case, may be equally important but is less obvious.

We think that general models will not lead to a giant leap without all of the right robot data. We also believe that smaller models outperform larger ones for many use cases on a number of critical dimensions like cost and speed while accounting for the majority of value available to robots.

Solving everything in a large general model is tempting: we’ve trained LLMs already. Leverage the trillion-dollar machine!

LLMs have strong semantic structure. Word embeddings put similar words close together, and (weirdly, beautifully) semantic distance in language often mirrors semantic distance in tasks.

So we get the appealing idea: use an LLM backbone, condition behavior on short text labels, and store many skills in one model. “Pick.” “Place.” “Stack.” “Insert.” Same model, many skills. That’s the VLA (video-language-action) dream.

But there’s a reason diffusion took off first in robotics.

LLMs are autoregressive: predict next action once → feed it back in → compounding error if wrong. The errors matter hugely when you’re controlling physical systems.

On the other hand, diffusion is iterative: denoise progressively → a single bad step doesn’t doom the rollout.

But there are challenges to making this work well at the architectural level.

LLMs were designed for tokens: discrete symbols, or words. Robots operate on continuous values: positions, velocities, torques. Numbers like 17.4343 instead of words like “seventeen.”

With LLMs, every digit becomes a token. Precision explodes token count, which means latency explodes too. Your robot gets slow, and a slow robot isn’t a particularly useful robot.

This is the core tension:

Robotics success so far has leaned heavily on diffusion-style control

LLMs are autoregressive and token-based

Physical actions don’t map cleanly to tokens

Pi has bridged this gap: they’ve found representations of robot action that play nicely with language-model infrastructure. That’s real, hard, and impressive work.

But here’s another spicy take.

We’re not working with language-model infrastructure because it’s the perfect architecture for robotics. It’s because we, as a species, have poured trillions of dollars and countless engineering hours into building LLM infrastructure. It’s incredibly tempting to reuse that machine.

So, despite its imperfections, taking an LLM and sticking on an action head to predict robot motions (all together known as a VLA) is the best way for us to train the base models that learn many skills from demonstrations across many different customers and tasks.

There’s also the “fast and slow” split: use LLMs as supervisory systems that watch, reason, and call skills, rather than directly controlling motors. Figure’s approach is a good example of that pattern.

The problem with general models is that they have to solve for everything. They are predicated on the belief that if you throw enough compute and data into a single huge model, you will be able to make a robot that can do almost anything. They solve for max variability: you can walk into a completely unseen environment with unseen tools, unseen equipment or fridge or stove, and you can handle all of that perfectly. And the objects are breakable. That’s a tremendous amount of variability to account for in one model, so the model needs to be huge.

Huge models mean models that are more expensive (at training and inference), harder to debug, and slower, which you can see in humanoid performance today.

BUT, and here is a key insight: parameter count scales with variability, not with value.

We think that most of the market can be unlocked by a surprisingly small number of parameters.

Let’s use the example of self-driving again. Apple published a paper on its self-driving work in which it states using just 6 million parameters for decision making and planning policy. Elon said recently that Tesla uses a “shockingly small” number of parameters for their cars.

This is orders of magnitude smaller than the hundred-billions or trillions of parameters we’re used to hearing about for LLMs, because LLMs need to be ready to answer almost any question imaginable at any time, and because each individual LLM user isn’t worth enough to fine-tune custom models for.

It’s the opposite case with robotics if you’re solving for a specific task with constrained variability. The model will need to know how to do a few things very well. Given the cost of deployment and the economic value created, it is absolutely worth fine-tuning a model for that use case.

That means we can distill our larger base model into much smaller models. Which we are. We ship really small models sometimes. They’re low parameter models that can solve, across the spectrum, a really useful number of things. And we can concentrate the robot’s limited compute on narrower problems, which leads to better performance.

We use small amounts of the right data to feed small models that are cheaper, faster, and can be better-performing than the large, general ones that they come from when fine-tuned on the right data.

Of course, the better, cheaper, and faster we are for each specific use case, the more broadly we will deploy, the faster we will learn, and the sooner we can eat more of the spectrum.

At least, that’s my bet.

Is Standard Bots Bitter Lesson Pilled?

My bet isn’t exactly the trendiest. It’s not fun betting against the magic of emergent capabilities.

In one of our conversations, Packy asked me if our approach was Bitter Lesson-pilled, referring to Rich Sutton’s 2019 observation that “the biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.”

He pointed me to the 2024 Ben Thompson article, Elon Dreams and Bitter Lessons, in which Thompson argues that starting with a bold “dream,” then engineering costs down to enable scale, beats cautious, incremental approaches and creates new markets.

Waymo looks like it’s in the lead now, Thompson argues, but its approach — LiDAR for precise depth, cameras for visual context, radar for robustness in adverse conditions, HD maps, a data pipeline, etc — is bound to plateau, because it’s more expensive and its dependencies make it less likely to achieve full autonomy.

Tesla FSD, on the other hand, is betting on end-to-end autonomy via vision (cheap cameras) and scaled compute. Use cameras-only at inference to keep vehicles cheap, harvest driving data from millions of Teslas to train large neural networks, distill expensive sensors and mapping used during training into a lightweight runtime, and compound safety through volume until Level 5 full autonomy everywhere becomes viable rather than geofenced Level 4. This is the Bitter Lesson-pilled approach.

I had to think about my answer for a second. I hadn’t thought about it and I wasn’t entirely sure.

It’s definitely a viable question. Could someone come in and just create a super, super intelligence that only needs to be communicated with through a super simple voice interface? I mean, theoretically, obviously, yes. Right?

Wrong. The truth is that you need the data to win.

You can’t be Bitter Lessoned by someone that doesn’t have the training data.

Tesla was only in the position to Bitter Lesson everyone because they had the distribution to collect the data in the first place. The iterative approach, Tesla’s Master Plan, is what enabled the Bitter Lesson approach in the first place.

The iterative, customer-funded approach, the one Tesla took and the one we are taking, is how you get the data that lets you benefit from scale. Thompson himself wrote, “While the Bitter Lesson is predicated on there being an ever-increasing amount of compute, which reliably solves once-intractable problems, one of the lessons of LLMs is that you also need an ever-increasing amount of data.”

The Bitter Lesson in Robotics is that leveraging real-world data is ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.

You can’t Bitter Lesson your way to victory if you don’t have the training data, and you can’t get the training data without deployment. What Sutton would really suggest, I think, is to get as many robots in the field as possible and then let them learn in a way that is interactive, continual, and self-improving.

We’re not there yet. We still have humans in the loop.

But the first step to all of this, and perhaps our company’s best hedge against the Bitter Lesson, is getting robots deployed to as many customers as we can, as quickly as we can.

What If I’m Wrong?

It’s hard to work in robotics for too long without getting humbled. This is an industry that has, for decades, fallen short on its promise.

So how confident am I that I’m right and basically the rest of the industry is wrong?

I mean, decently confident, confident enough to spend my most productive years building this company. I’m confident that our approach is differentiated and logically consistent. But fully confident? No.

It’s worth saying explicitly that this isn’t a case of us versus the rest of robotics. Some of the people I respect most in the field are taking the opposite bet.

Lachy Groom, the CEO of Pi, is a close friend and led the Series A in Standard Bots. He’s building with a foundation-model view of robotics, and I think this work is important. We talk about this stuff all the time and we both want the same thing: to see tons of robots out in the world, no matter whose approach gets us there fastest.

If the foundation-model view wins out, though, it’s hard to see how any one company will be able to winner-take-all the model market on compute and algorithms alone. There are now at least four frontier LLM labs with basically the same model capabilities. On-demand intelligence, miraculously, is becoming a commodity.

If you were going to run away with this market, my bet is that you’d have to do it with data and with customer relationships, kind of like Cursor for robotics.

Let’s say, for argument’s sake, that Google, Skild, and Physical Intelligence all solve general physical intelligence. In that case, I think whichever company actually owns the customer relationship has the power. That company can just plug in the lowest bidder on the model side.

This is related to the bet that Packy argued China is making in The Electric Slide: if I’m the company that can build robots and sell them to customers, and particularly if customers are already getting value from Standard Bots, then I want the models to commoditize. I want them to be as powerful as possible. Commoditize your complements.

It’s good for us, at the end of the day. Getting a product in the field, selling to customers, and iterating is both a competitive advantage and a hedge. All I care about is the advantage, though.

We believe, like so many of the people working in our industry do, that there will be no bigger improvement to human flourishing than successfully putting robots to work in the real economy. We are on the precipice of labor on-tap, powered by electrons and intelligence. That means cheaper, better goods. It means freeing humans from the work they don’t enjoy. Being a farmer is more fun when you don’t have to take the cow’s temperature yourself. It means that the gap between thought and thing practically disappears. And those are just the first-order effects. We can’t know ahead of time what fascinating things people will dream up for our abundant robotics labor force to do; all we can know is that they will be things people find useful.

We all believe this. We all want to produce a giant leap for mankind. The open question is how we get from here to there.

I believe the way to build the world’s largest robotics company is to eat the industry one use case at a time. And I’m so hungry I could eat a cow.

Big thanks to Evan for sharing his knowledge, to the Standard Bots team for input, and to Badal for the cover art and graphics.

That’s all for today.

For not boring world paid members, I played around with Claude to produce some extra goodies. We made an annotated bibliography with links to papers that support (or push back on) Evan’s argument from both the robotics and business strategy side and a GAME. Members can also ask Evan questions on today’s cossay.

Join us in not boring world for all of this and more behind the paywall.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Not Boring by Packy McCormick to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.