Welcome to the 2,105 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! 🤯 If you aren’t subscribed, join 36,522 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen here or on Spotify.

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Future

Future is the 1-on-1 remote personal training app I use to stay in shape despite my sedentary profession. I’ve been working with my coach, Alex, for over three months now. I missed a workout in that first month, but thanks to the accountability he provides, plus the fact that I have to share my stats with all of you, I haven’t missed one in the last two months!

That said… I did lose the 2021 Challenge to Mario and Rishi. I owe them each a share of Roblox, but I’m actually cool with it. Future has kept me consistent with a baby and an unstructured schedule. Four expertly-designed workouts a week, every week.

If you want to build a consistent, high-quality workout routine, or amp it up and get in the best shape of your life, get yourself a Future account and your very own professional Coach.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

One of my favorite parts about writing this newsletter is getting to meet incredibly smart people who are so much more knowledgable about their focus area than I could ever be. If I’m really lucky, those people happen to be writers, too, and I get to team up with them. Today, I’m lucky.

Marc Rubinstein is a former financial sector-focused hedge fund manager who writes one of the best financial sector newsletters there is: Net Interest. Marc has written about everything from newer players like Ant Financial and Facebook’s Diem, to huge banks like Citi, to explainers on things that only industry insiders would know. You should subscribe now if you’re interested in … money.

I’ve wanted to write about today’s topic for a long time, and Marc was the missing piece in my Jack Dorsey mental puzzle.

Let’s get to it.

Jack of Two Trades

You Don’t Know Jack

Why is Jack Dorsey so much worse at being the CEO of Twitter than he is at being the CEO of Square?

That was the question that kicked this whole thing off. After Marc Rubinstein wrote Hip to Be Square in December, I emailed him with that question. Marc is a former hedge fund manager who writes the brilliant newsletter Net Interest about all things finance and fintech. His fund participated in the Square IPO back in 2015. I understand Twitter, Marc understands Square. Together, we could crack this.

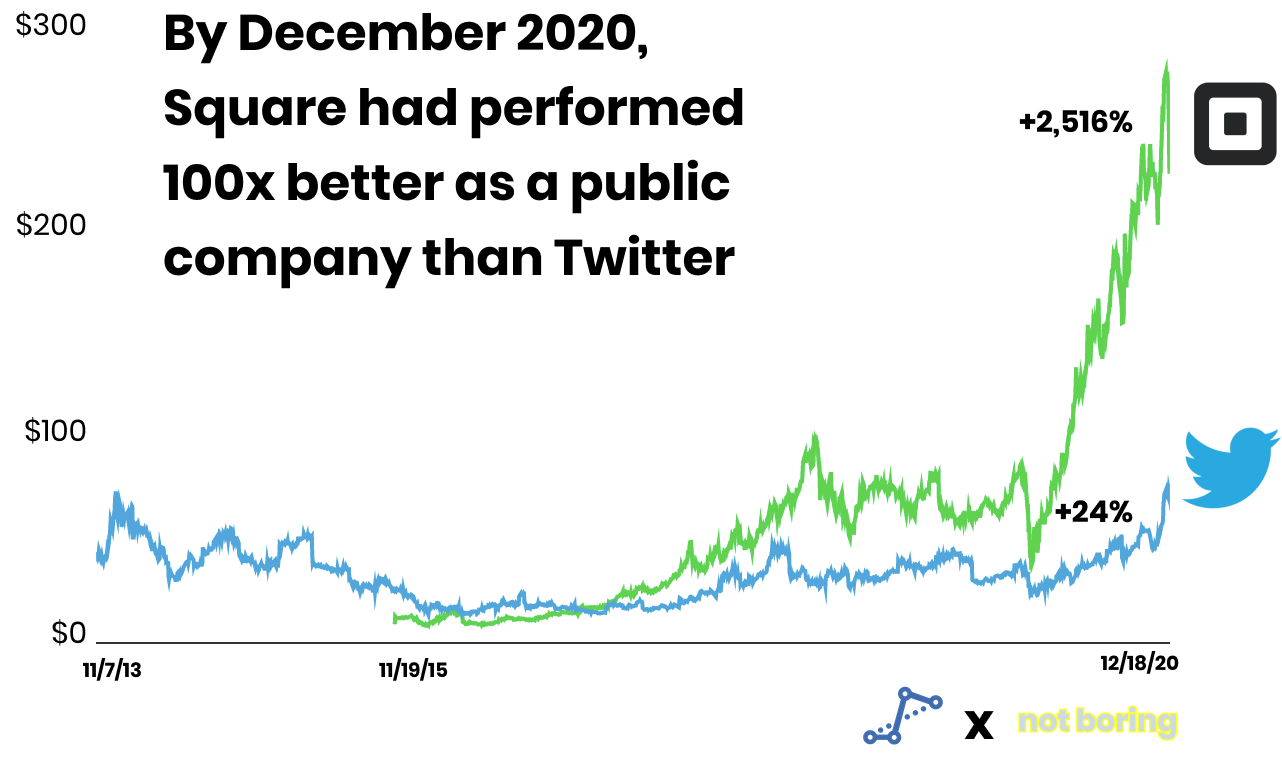

The companies’ relative product velocity and stock prices make the contrast stark. Since its initial public market struggles, Square has been an absolute rocketship. If you had bought $SQ at the November 19, 2015 IPO price of $9, you would have been up 25x by the time that Marc wrote about the company on December 18, 2020. $TWTR, meanwhile, was up only 24% between its November 7, 2013 IPO and December 18. Jack’s Square had performed 100x better than Jack’s Twitter, despite two years less time in the public markets.

The question was so obvious -- Jack was clearly a terrible CEO at Twitter and a great CEO at Square -- and we certainly weren’t the first people to ask it. Elliott Management launched an activist campaign in February 2020 that rested on “Jack is the CEO of two companies and he’s doing a bad job at this one” as one of its core tenets.

But despite the obviousness of the question, it didn’t have an obvious answer. So we decided to team up, Marc contributing his knowledge on Square, me adding my perspective on Twitter, to see if there was some way to … square … the apparent contradiction. We agreed to publish after Square announced Q4 earnings in February.

And then… Twitter got its groove back. It acquired Substack competitor Revue, launched Clubhouse competitor Spaces, reported strong earnings, and blew expectations out of the water with an ambitious and aggressive Analyst Day last week. Jack even acknowledged that the company has moved way too slowly, and set a goal to double the product cadence while doubling revenue by 2023. Since Marc and I first spoke on December 18th, Twitter is up 37%.

The obvious question -- why is Jack such a great Square CEO and such a bad Twitter CEO -- became a lot less obvious. Some new, more illuminating ones emerged in its place, such as: “Assuming Jack runs the companies in largely the same way, why might they perform so differently?” The answer to that explains why it’s so much harder to actually run companies than it is to write about them and come up with fun product ideas.

The differences in the way Jack runs his two companies have been (literally) litigated into the ground, but exploring the similarities, and what they say about both companies’ futures, is a more fascinating endeavor. Zooming out and looking ahead, Square and Twitter have a lot more in common than meets the eye. Today, we’ll unpack that, by covering:

Jackground

Back to Square One

Putting the Network Into Square

Old Twitter

Twitter’s New Groove

Back to the Original Question

And look, we get why Jack’s dual roles make people uncomfortable. No one’s ever done it quite like him.

Jackground

Some Twitter shareholders don’t love the fact that Jack Dorsey runs both Twitter and Square, for reasons ranging from time management to performance to conflict of interest. It’s not surprising that they’re concerned: very few people run two public companies.

Steve Jobs did it. After he was ousted from Apple, Jack’s idol acquired Lucasfilm’s animation studio and renamed it Pixar. Jobs took the company public in 1995, returned to Apple as CEO in 1996, and ran both companies until Disney acquired Pixar in 2006. That was Steve Jobs, and even he, the Zeus of tech CEOs, got kidney stones from the stress of running two companies.

Carlos Ghosn ran both Renault and Nissan after orchestrating the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance which tied the three companies through a cross-sharing agreement. The multi-CEO role made sense because of the close relationships between the companies, and Ghosn apparently had few interests outside of work besides watching soccer. (Today, Ghosn is an internationally-wanted fugitive, hiding out in Lebanon with an Interpol red notice on his head, after allegations by the Japanese government that he underreported his salary and grossly misused company funds, so...)

Elon Musk leads both public Tesla and might-as-well-be-public $74 billion SpaceX. He’s a hard charging mega-genius who does more at each of those companies than most CEOs do at one, and it’s impossible to argue with his performance.

And then there’s Jack.

Jack is laid back, travels often, already worked from home one day a week pre-COVID, told Forbes that he “spend[s] 90% of my time with people who don’t report to me, which allows for serendipity, because I’m walking around the office all the time,” and was pushed out of Twitter, when he ran just that one company, in part because he would leave the office early to take fashion design classes. Ev Williams famously gave him an ultimatum in the early days: “You can either be a dressmaker or the CEO of Twitter.” In 2019, he made waves by saying that he wanted to move to Africa. His resume does not scream workaholic.

As Twitter’s public market performance dragged between 2013 and 2020, shareholders became increasingly vocal and litigious. In December 2019, Scott Galloway called for his ouster. In March 2020, Elliott Management and Silver Lake took seats on the board as part of an activist campaign that called for Jack’s head. Just last week, a shareholder sued Jack and Twitter’s board, claiming that Jack breached his fiduciary duty by giving advertisers access to users’ private data, often to the great benefit of Square, Jack’s ownership in which is worth nearly 8x as much as his Twitter holdings. (Square shareholders don’t seem to mind. Winning takes care of everything.)

Jack would argue that hours worked != quality of work. On Rich Kleiman’s The Boardroom: Out of Office podcast, Dorsey said that he would, “Rather optimize for making every hour meaningful, or every minute meaningful, than I would maximizing the number of hours or minutes I’m working on a thing.” He called the idea that you need to work twenty hours and sleep four because you read that Elon Musk does, “bullshit,” and detailed a morning routine that includes meditation and an 80 minute walk to work while listening to podcasts, plus an intermittent fasting routine that has him skip breakfast and lunch. He told Kleiman he works at Twitter in the morning and Square in the afternoon and evening, before making dinner and winding down.

Jack’s publicly-stated philosophy is that by focusing on fewer decisions with more attention, he’s able to make better decisions when they matter most. Plus, he doesn’t even believe that he should be making most of the decisions, opting instead to put more power in the hands of the people around him. On a February 2019 Twitter earnings call, he said:

I think my job as a CEO whether it be at one company or two is very simple. I need to build optionality for the organization, and that is optionality within leadership. So the way I think about it is I want to make sure that we're building leaders around me that I could imagine carrying the company forward.

Hearing that at the time, when Twitter was trading 32% below its IPO price after five years as a public company, it must have sounded like, to steal a phrase from Jack, bullshit. Twitter employees have complained that it’s hard to know who to go to for a final call when Jack’s MIA.

But now, two years later, with Twitter’s stock price up 157% since that quote, and after an Analyst Day at which the company announced a bold new plan and an inspired product vision, it’s worth considering whether Jack’s self-removal from the weeds really does allow his companies to make better strategic decisions.

As I wrote in How Twitter Got Its Groove Back, “Whether accidentally or through an ultra-attuned third eye and a Zen-like ability to withstand half a decade’s worth of criticism, he’s put Twitter in a surprisingly strong strategic position.”

In other words, maybe Jack is running Twitter a lot more like he’s run Square than meets the eye.

Back to Square One

Square never started out imagining that one day its product would feature in hip-hop lyrics. It started out a whole lot more boring than that: as a dongle that retailers could plug into their phones to swipe credit cards.

Jim McKelvey had the idea in his glass making studio in St Louis, Missouri. A customer came in with her eye on an orange-yellow, double-twist glass spout for her bathroom. The spout had been gathering dust on McKelvey’s shelf for several years, so when the customer pointed to it, he was keen to make a quick sale. Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to take her credit card, so the deal fell through. After she’d left, he looked down at his phone and wondered – given what else it could do – why that device couldn’t process credit cards.

McKelvey had known Jack Dorsey since Jack was sixteen. Jack’s mum, Marcia, ran a coffee shop that McKelvey would frequent. When he wasn’t glass blowing, he was managing a digital publishing business and, through Marcia, he roped Jack in as an intern. They kept in touch and in 2008 McKelvey called Jack to kick around some ideas for a new venture. Jack had just been ousted from Twitter, so they agreed to pair up and pursue the dongle idea.

Jack and Jim’s Big Idea was less the technology inside the dongle – which they didn’t even patent – and more that there was a huge untapped market out there of merchants too small for the traditional payments industry to target. The key was to keep costs down, which they could do by aggregating the huge volume of small transactions that these small merchants booked. At the time, there were 30 million businesses in America doing less than $100,000 of annual sales; 24 million of them didn’t accept credit cards – that was the pair’s market opportunity.

They called their company Squirrel – until they spotted someone else had taken the name (that someone being Apple). So Jack did what he’d done at Twitter. Today, Twitch is the world’s leading live streaming platform for gamers. But it was the original name of Twitter, in homage to the motion people make when their phones buzz with a new message. The name didn’t resonate with the team so they opened up a dictionary to find something close. From Twitch to Twitter. And from Squirrel to Square.

Over the next few years, Square would make itself invaluable to its customers. Drawing inspiration from Apple, it combined hardware and software into an integrated system. The dongle itself was given away for free and merchants would pay a very simple fee linked to transaction volume. The integrated systems allowed Square to add new features that entrenched its position with customers – features like working capital, invoicing, and payroll, all to help merchants run and grow their businesses.

None of this was especially networky though. Just because one merchant has a dongle doesn’t mean the merchant next door needs to get a dongle. Sure, the sleek white square may have looked cool enough for people to want one, but the social dynamics underpinning that weren’t intrinsic to the business model.

In addition, Square was giving up a lot of its economics. In payments, there’s a trade-off between being part of an open network and being a closed network. The open network, operating on the rails of card associations like Visa and Mastercard, allows a cardholder flexibility to use their card almost anywhere. But participants have to share the economics. In Square’s case, merchants pay a rate of ~3% on transactions, but Square has to distribute ~2% out to others in the network, leaving only ~1% for itself. In a closed network, the operator maintains their own ledger and can move money from the cardholder side to the merchant side freely, retaining all the economics for itself.

Square’s first attempt to bridge this gap was with Square Wallet. The wallet gave consumers payment functionality which they could use at participating merchants. Square would be able to keep both the consumer side of the transaction and the merchant side within its own walls. It wasn’t a success. Perhaps it was too early, perhaps merchant adoption wasn’t ubiquitous enough, perhaps Square didn’t invest sufficiently in consumer acquisition. Whatever the reason, it was closed down. Its replacement, Square Order, didn’t fare too well, either.

That was fine. With a stable merchant business as its base, Square hasn’t been afraid to experiment on new businesses that have the potential to both stand alone and ultimately bridge the gap. One such experiment that did stick was Cash App.

Putting the Network into Square

Introduced as Square Cash in 2013, Cash App was devised during a hackathon as a way to make peer-to-peer payments – splitting the check at a restaurant, sharing the cost of an Airbnb, that kind of thing. By the end of 2016, Cash App had 3 million monthly average users; today, it has more than 36 million.

Unlike the merchant side of the business, the consumer Cash App side exhibits very clear network effects. If your friend has it, and you want them to pay you back, you need it too. Square seeded these effects with viral marketing campaigns and money giveaways, using Twitter as a particularly effective acquisition tool. ARK Invest shows how Cash App’s monthly active users correlates with its Twitter follower count. The strategy kept customer acquisition costs exceptionally low: last year, they were less than $5 per customer.

In addition to viral marketing, the company reprised the playbook that fueled growth so effectively on the merchant side. That playbook has three elements: make the product free and simple to use, target an underserved customer base, and layer in adjacent services.

In this case, the underserved customer base is the underbanked segment of the population, for whom Cash App provides an alternative to a bank account. Although the earliest Cash App adopters came for the network – the ability to pay their friends – more recent adopters have come for the utility of a functioning bank account substitute. That’s especially been the case over the period of the pandemic where Cash App has been used to receive stimulus funds.

Layering in adjacent services is the key to unlocking economics in what is at core a free product. Over the past few years, Cash App has added lots of new products: rewards (Boost), stock trading, Bitcoin, direct deposits, business accounts, and Cash Card. The contribution these products make is broadening. While only one of them made more than $100 million in gross profit in 2019, four of them surpassed that in 2020.

But the model isn’t simply about cross-selling; it’s about engagement, too. Cash App benefits from the compounding effect of growing its customer base while also increasing engagement and monetization per customer. Around a quarter of Cash App monthly active customers engage on a daily basis. That’s not as high as Twitter, but for financial services, it’s pretty good.

In the fourth quarter, the average gross profit per customer reached $41. Customers who use multiple products generate 3-4 times higher gross profit than the average. Cash Card is the most popular – one in four Cash App customers use it – but Bitcoin is catching up, at one in ten. The compounding comes from the higher rates of engagement customers with multiple products produce. Those who use the Boost rewards feature, for example, spend two times more on their Cash Card than other customers.

Acquire, engage, sell. It’s a simple but highly effective model.

This year, Square is going to turbocharge that model:

They plan to do $800 to $900 million of incremental investment.

They continue to look for new ways to connect product lines within Cash App.

And they are getting closer to being able to mesh the consumer facing Cash App side of the business with the merchant facing seller side.

Cash App began 2020 contributing just over a quarter of the group’s combined gross profit, but it left 2020 contributing nearly a half. As it hits scale there will be opportunities to close up pieces of the network, picking up where Square Wallet failed. Jack said on his recent earnings call, “We’ve done a lot of internal connections between the two ecosystems, and now we’re focused on more of the customer-facing connections.” No doubt we’ll hear about it on Twitter when it happens.

Old Twitter

Square users came for the utility as Square added in a network. Twitter users came for the network as Twitter searched for its utility.

Square’s dual-tracked growth strategy has gone something like this: focus on the core customer -- the small merchant -- and add features to the core product in order to retain and grow with them, experiment with new ways of building a networked product in parallel in lightweight ways that don’t mess with the main product, and ultimately combine the two to create a closed network.

Twitter, on the other hand, started with the network, and all of the inherent messiness that large networks of humans imply, and tried to build, monetize, and experiment with it while keeping it from breaking and figuring out its utility. Oh, and it’s done it all under a revolving door of leaders with different priorities and varying vision horizons.

As a result, Twitter and Square’s product development paths have looked something like this:

For most of Twitter’s history, it felt like it was being pulled too fast, like it was playing catchup and paying for its past sins. In engineering, they call those past sins “technical debt.”

Before Twitter, there was Odeo, an audio blogging platform founded by Noah Glass and backed by Ev Williams. Jack was just a blue-haired Odeo engineer then. When Apple released Podcasts in 2006, the team decided Odeo was dead on arrival, and scrambled for ideas. Jack brought Noah and Ev the idea for public status messages, based on a similar feature LiveJournal (RIP) had just rolled out, and after a two-week sprint, Twitter was born.

After a slow first year, Twitter caught fire when it won Best Startup at SXSW in 2007 and attracted celebrities like Ashton Kutcher and Justin Bieber, who raced CNN to become the first account with 1 million followers (Kutcher won). Twitter got bigger, faster than anyone on the team imagined, and as it caught fire, its infrastructure -- mainly built during that two-week sprint -- was burning down. Twitter’s “fail whale” was a familiar sight to any of the platform’s early users.

In 2008, concerned that Jack was too preoccupied by extracurricular pursuits like fashion design classes, Ev Williams and the board removed him as CEO and put Ev in charge. He lasted two years, until the board fired him and replaced him with his friend and Twitter COO, Dick Costolo, in 2010.

People bemoan the fact that Twitter was neck-and-neck with Facebook in 2010 and blew it, and point to that as yet another reason that Jack needs to go. But a lot of the blame can rightly be placed on Costolo’s shoulders.

Under Costolo, Twitter professionalized, and it did some great things: it started making money, via Promoted Tweets and Promoted Trends, brought on Adam Bain to run revenue, and went public in 2013. But it also made bad moves that put Twitter in the predicament it was in coming into 2020, including:

Shut out third-party developers

Launched Twitter Music for iPhone

Slowed user growth and engagement

Made a bunch of acquisitions, including Tweetdeck, MoPub, TapCommerce, Niche, and Vine, which it famously shut down in 2016

Importantly, it made the mistake that professional, non-founder CEOs are often criticized for: focusing too much on short-term revenue optimization at the expense of long-term strategy. When the company failed to even optimize revenue in the short-term, missing quarterly targets throughout 2015, Costolo was out, and Jack was back in, at least temporarily.

At the time, Jack was already running Square, and accepted the Twitter CEO position on an interim basis. Interim has turned into more than five years at the helm.

When Jack took over, he inherited the equivalent of a baseball team that gutted its farm system to go all-in on winning now and lost. In Q4 2015, Jack’s first as returned CEO, Twitter experienced the first quarter in its history of declining Monthly Active User (MAU) growth.

The Twitter Jack came back to had a Frankenstein infrastructure and an ad product that was nearly impossible to use on a self-serve basis, meaning that the majority of its ad revenue came from large brands’ awareness budgets as opposed to more measurable and faster-to-sale direct response advertising. And Twitter, in its rush to grow MAUs and go global, had started to become the cesspool that it’s criticized as being today.

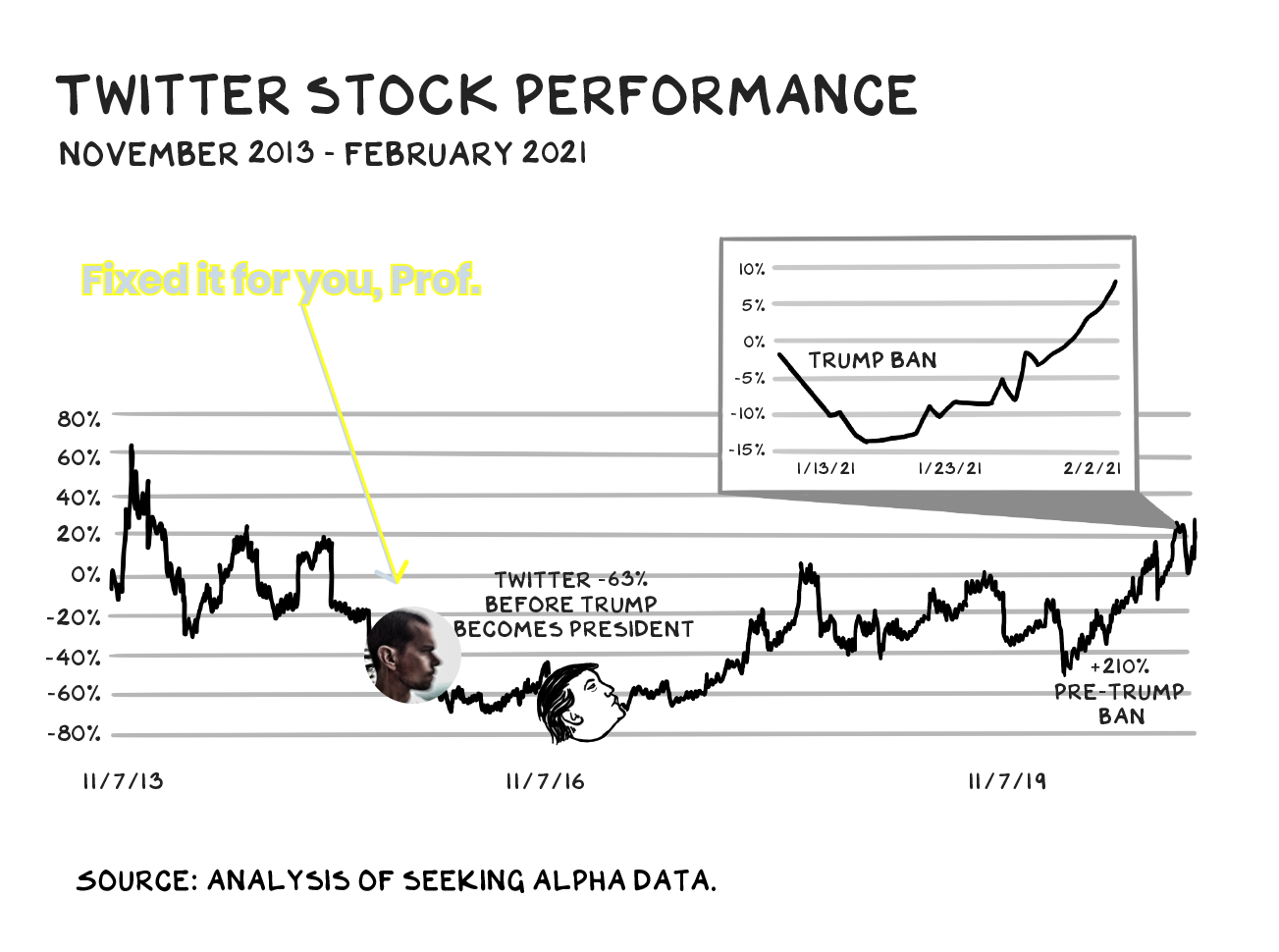

In the piece that Professor Galloway wrote on February 5th, Overhauling Twitter, he included a Twitter stock chart as part of his arsenal of arguments that Jack needs to go. He argued that Trump’s presidency saved the platform, and I called him out for using a large version of Trump’s head to paper over nine months of flat growth post-election. I missed something obvious, though…

Most of the 63% decline in Twitter’s stock price that he highlights came before Jack was reinstated as CEO! The Prof is using Costolo’s performance to argue that Jack isn’t fit to be CEO. (And Twitter, of course, is up 36% in under a month since the Prof hit publish haha.)

Certainly, Jack has not acted quickly over the five years since he retook Twitter’s top spot. He, too, got distracted by flashy external things, like the rights to the NFL’s Thursday Night Football. He didn’t fix Twitter’s ad products soon enough.

But if you were going to fire Jack for his underperformance, where on the graph above do you do it? In his first year as CEO? During the run up the company had in his second year? You could make the case that you could have fired Jack between 2017 and 2019. But Jack should be safe now.

Because if you look at the past two years and Twitter’s recent announcements, the question isn’t “Why is Jack worse at being Twitter’s CEO than Square’s?”, it’s “Doesn’t it kind of look like Jack is making some Square-like moves at Twitter?”

Twitter’s New Groove

Part of the key to Square’s staying power, the reason it was able to stay alive long enough to iterate its way to Cash App, was that it was building off a stable base. Square’s merchant (or “Seller”) business grew solidly, like B2B products can, with a clear, if unspectacular, business model from day one. That’s something that Twitter never had.

So in 2019, after a sluggish first few years in his second tenure, Jack decided to start fresh and rebuild Twitter’s ad infrastructure from the ground up. When the pandemic hit, it redoubled its focus on its revenue products. It also spent a ton of time and attention on what it calls “health,” reducing toxicity in the Twitter conversation, and on surviving the 2020 US Presidential election. That is unsexy work that takes time to show up in the numbers.

Would a full-time, focused, hard-charging CEO have fixed the infrastructure earlier? Maybe. Or they may have put more emphasis on ad sales and MAU growth, created new formats on top of existing infrastructure, and tried to fight their way out of the hole.

In the uncharitable interpretation, Jack’s laissez-faire, part-time CEOship cost Twitter years of valuable development time. In the charitable interpretation, Jack’s meditative approach was exactly what the company needed in order to pause, reset, rebuild, reprioritize, and unleash a wave of creativity. In either case, it’s hard to interpret what’s going on at Twitter today as anything but positive.

Of course, there are the numbers. Twitter reported earnings the day after I wrote How Twitter Got Its Groove Back, and everything continues to move in the right direction.

More importantly, with its infrastructure rebuilt, Twitter is setting its sights on the future, where Jack operates, like Square can. It’s finally doing all of the things that armchair analysts like me, who don’t have to worry about paying down technical debt, have been saying it should do for a while.

In How Twitter Got Its Groove Back, I covered Twitter’s push into newsletters (with the acquisition of Revue) and audio chat (with Spaces). They’re savvy moves given Twitter’s position as the top-of-funnel for the Creator Economy, and in any other year of Twitter’s history, they would have been enough to satisfy Twitter and keep it busy. But this is the new Twitter.

On Thursday, Twitter held its Analyst Day. Jack kicked off the event by confronting the three main reasons people don’t believe in the company: “we're slow, we're not innovative, and we're not trusted.”

We’re Slow. Jack agreed that the company has been slow, because it’s been working itself out of technical debt for years.

We’re Not Innovative. Jack tied lack of innovation to slowness -- “If we can't ship code faster, we can't experiment and iterate, and every launch comes with massive expectation and cost.” He also highlighted that innovation isn’t always flashy; they made the decision to deprioritize everything except making the core timeline experience better, and the results have shown up in the increase in monetizable Daily Active Users (mDAUs). As someone who joined Twitter in 2009 but only became an addict in 2019, I can attest to the fact that it’s working.

We’re Not Trusted. Again, Jack agreed. He committed to more transparency (already evident in the way the company is building Spaces in public), giving people better moderation tools, enabling a marketplace approach to relevance algorithms, and funding its open source media standard called Bluesky.

While all three criticisms are important, speed and innovation are the most directly relevant to the Square comparison, and Twitter wasted no time proving they were serious.

When Jack handed over the mic, his team made two new major product announcements, within a month of Revue and Spaces. That feels a lot more Square-like than Old Twitter-like. Twitter’s Head of Consumer Product, Kayvon Beykpour, announced Communities, and its Chief Design Officer, Dantley Davis, Announced Super Follows.

Super Follows, which let Creators charge followers a monthly rate for more access, are exciting, not just because they’re new and shiny, and not just because they validate my prediction for Twitter’s subscription products (one that allows top Creators to monetize and takes a cut) versus the Prof’s (make people with large followings pay a monthly subscription fee). Super Follows are an opportunity for Twitter to go from an open network that leaks value to everyone else, to a closed one, and to combine the two ecosystems they’ve been building and create an internal economy… kind of like Square.

What is Twitter Building?

Remember the playbook that Square runs on both the merchant and Cash App sides of the business?

That actually looks a whole lot like what Twitter is doing.

Make the Product Free and Simple to Use. Twitter has always been free, but it hasn’t always been simple to use. The fact that over a billion people have created a Twitter account and there are only 192 million mDAUs speaks to that. Twitter is working to fix that challenge by focusing on Topics, which make it easier for people to get value out of Twitter immediately without a curated follow list.

Target an Underserved Customer Base. Twitter spent 15 years trying to figure out who and what it’s for. Given its flurry of recent moves, it feels like it’s finally figured out its core customer base: Creators. This group has actually been underserved for a long time in terms of its ability to get distribution, the most valuable asset for any creator. Small businesses have Facebook, big brands have nearly every channel imaginable, video creators have YouTube and TikTok, hot people have Instagram, but writers, podcasters, analysts, comedians, and other more intellectual creators haven’t had a reliable growth or monetization channel. Now they have Twitter.

Layer in Adjacent Services. With the infrastructure rebuild under its belt, Twitter (finally) began layering in adjacent services at a Square-like pace, introducing Revue, Spaces, Super Follow, and Communities in the first two months of 2021. With a stated goal of doubling its development velocity by 2023, we suspect this is just the beginning.

The ecosystem that Twitter is building looks a lot more like Square’s than other social networks’, too. Square built up two ecosystems -- merchants and Cash App -- and is working to connect them.

Twitter has two ecosystems, too. They were merged from the beginning, which created a lot of the messiness -- the experience for a Creator is so much different than that of a consumer -- but makes the future promising if indeed they’ve figured it out.

Twitter’s merchant equivalent are the Creators on the platform. Until now, Twitter has been an open network and Creators haven’t had a way to monetize directly, so they’ve built audience on Twitter and made money off-platform. Its consumers are Cash App, the millions of individuals bound together by a network and an internal currency -- likes and retweets -- that they spend on Creators. With Twitter’s recent moves, it’s moving to close the network and let Creators build audience and a business in one app.

Given Jack’s experience at Square, we wouldn’t be surprised to see Twitter roll out its own internal currency (whether itself or via partnership with Square). In a way, it already has one -- likes and retweets. We would imagine that Twitter will come up with innovative ways to turn attention into currency. We would certainly be willing to give someone free Super Follow access if they brought us 100 relevant followers, for example. Since Twitter controls the entire ecosystem, it can experiment with value exchanges in ways that other platforms can (See: Facebook’s Diem).

Over time, we will see Twitter, like Square, add more products into the combined ecosystem. eCommerce is a no-brainer move at some point, as are improvements to the DM and Bookmarking experience. Twitter could even charge Creators for those improved products with money they’re already making in the app from Super Follows to save on transaction fees.

With the addition of Super Follows, Twitter is in a new spot: the lead. It will be the first major US social network with subscriptions, a way for Creators on the platform to make money directly from consumers on the platform. It will go from being the leakiest platform to the one that has the potential to capture the most value within its walls.

It feels weird to be optimistic about Twitter’s roadmap, but now that Old Twitter is finally New Twitter, fifteen years in and five years after Jack’s return, Twitter users and investors can finally look at Jack’s Square tenure as a good indicator of what’s to come instead of as a distraction.

Back to the Original Question

So why is Jack so much worse at being the CEO of Twitter than he is at being the CEO of Square?

Well, we don’t think he is.

Jack came into Square with a clean slate and his early Twitter experience under his belt, and he built something fresh, from scratch, with the thoughtfulness and infrastructure in place to scale and experiment. It got some things wrong, moved on, and iterated into Cash App, which has breathed new life into the company. Combining the merchant business and Cash App may give Square the holy grail of financial products: a low customer acquisition cost, closed network with an increasing number of opportunities for engagement and monetization.

Jack came back into a Twitter that was a broken, hobbled together mess on the engineering, business, and product side. The company has had to deal with regulation and being hauled in front of Congress, while Square has been able to avoid regulatory clashes (so far). Maybe a full-time CEO would have fixed all of that more quickly, but five years later, Jack is where he was a few years ago at Square: a core product that’s humming, strong infrastructure, and an appetite for innovation.

Twitter Jack still has a lot to prove. Twitter’s ad products are showing promise, but the revenue they generate is still relatively small. The company has announced cool products, but some don’t even have scheduled launch dates. That said, the narrative and momentum are back on Jack’s side. It’s going to be hard to push him out when things are going well, and with time, velocity, and the attention of the world’s most valuable users, Twitter, for once, has the deck stacked in its favor. The future is bright.

It’s a stretch to say that Jack planned this all along. Too many things had to fall into place in just the right way. And giving Jack too much credit might be too much founder-hero-worshipping; it’s clear that the people below Jack at both Twitter and Square are the ones doing a lot of the hard work to make all of this happen.

But as it stands, Jack currently runs two companies with combined market caps of $165 billion and a clear path to $500 billion in combined market cap within five years. He’s built two companies that have had a bigger impact on giving the Power to the Person than nearly any other -- Square by “blurring the lines between B2C and B2B” and giving small businesses a growing suite of ecommerce and financial tools, Twitter by being the place that the Creator Economy goes to build (and now monetize) an audience.

Now that Twitter investors feel less slighted by the time Jack spends at Square, maybe there’s even the potential for the two companies to work more closely together, to combine the two ecosystems they’ve built to make it easy for Square’s small businesses to reach customers on Twitter, and for Twitter users to pay their favorite Creators with Cash App.

Jack designed his system such that he can stay above the fray and plan what’s next while his deputies do the hard, day-to-day work. Some might call that laziness, some might complain about his trips to French Polynesia or his plans to move to Africa, but… it’s working. Twitter and Square have more optionality today than nearly any other companies on earth, just the way Jack wanted all along.

Thanks to Marc for teaming up on this and dropping Square knowledge and Dan for editing!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading, and see you on SUNDAY for a special edition,

Packy