[untitled]

building the operating system for music

Welcome to the 149 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last week! If you haven’t subscribed, join 235,233 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today’s Weekly Dose is brought to you by… Speakeasy

Speakeasy recently raised $15M to revolutionize REST API development.

Even the most gifted craftsman needs the appropriate tools to build something they’re proud of. Unfortunately, the API tooling ecosystem is still stuck in 2005.

Speakeasy wants to make it trivially easy for every developer to build great APIs. To make that dream a reality, Speakeasy is building a platform to handle the heavy lifting of API development and unburden developers to focus on refining the business logic.

From fast-growing innovators like Vercel, Mistral AI, and Kong to hobby projects by solo devs, engineers use Speakeasy to accelerate their API development and adoption.

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Tuesday! Late November, the sun is still shining in New York City, and I get to bring you my most different Deep Dive in a long time.

In early 2022, I invested in a company called [untitled] that’s building an app for music creators. There was something about Dancho and José, the longtime friends and co-founders of [untitled], the way they approached product and the way they loved the creative process.

Fast-forward: [untitled] recently raised an $18 million Series A led by a16z and crossed the 100k Monthly Active Users mark. It’s been used by the artists making #1 hits like Million Dollar Baby.

(If you want to be a part of the magic, you should check out the [untitled] job site.)

That an app (!) for music (!) creators (!), human (!) music creators no less, is doing so well in 2024 is surprising. Apps are dead. Spotify won human music. AI is coming for what’s left. And yet…

So this is a Deep Dive on how to build a product that creative people love and make more people create.

Let’s get to it.

[untitled]

We were standing upstairs at Elsewhere, me, Dancho, and Stephen, before the show, when FearDorian came over to say hey. The nineteen-year-old was in Brooklyn to perform, up from Atlanta, and before he went on, Dancho, one of the co-founders of [untitled], wanted to ask him how he was liking the app.

“It’s fire,” he told us, before launching into a story about how he used to keep all of his beats on a hard drive, until his hard drive got corrupted, and even after he tried to format it, he lost them. Now, all of his beats are in his pocket, right there and ready to use when inspiration strikes. He pulled out his phone to show us – beat after beat after beat. Stephen captured the conversation, you can listen to it here, like you were there.

[untitled] calls itself “A sacred place for your work-in-progress music.” It’s hard to pin down where its role starts in the song creation process and where it ends.

When [untitled] started, it was just a better place to store tracks that you recorded and edited somewhere else, and a place to share them with collaborators, get notes, try again.

The way artists did it before [untitled] was that they’d record vocals in Voice Memos, keep beats in the Notes app, maybe full tracks in the Notes app, maybe save them to Dropbox or, like FearDorian, a hard drive. Share a static link, get static feedback, back to the drawing board. No version control.

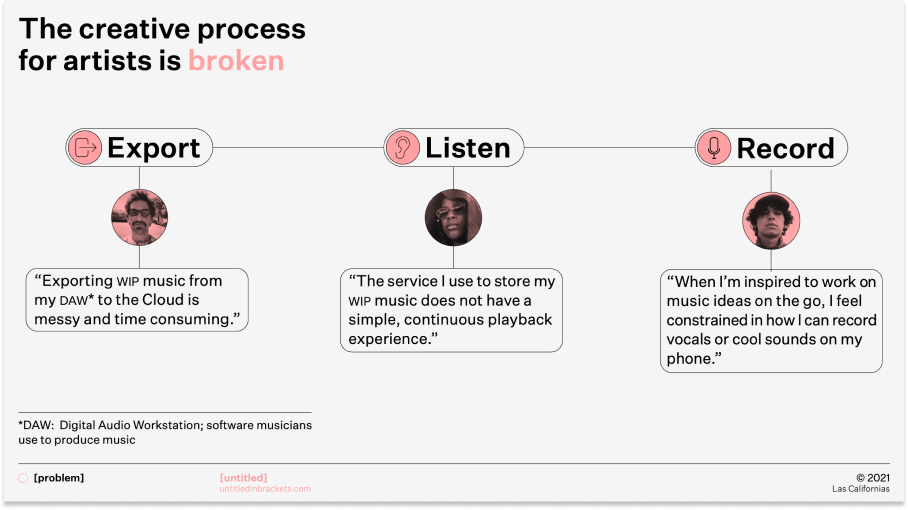

It worked – songs got made, of course – but talking to artists and producers that night in Elsewhere, they confirmed what Dancho and his co-founder and lifelong friend José had told me from the first time we met: no one liked that experience. It was friction that gummed the creative works.

The other thing I heard from artists that night was that they were using [untitled] and loving it, loving it enough to tell their collaborators to start using it, too.

Al Carlson was a producer, the person who gave Stephen, [untitled]’s head of community, his start in the music business. He’d been in the game for a long time, and worked across genres. He told us about an album he was working on with the cult indie-phenom Roy Blair and an opera album with Davóne Tines he’d just engineered. He used [untitled] for both. When Al walked away, Dancho told me he’d produced a track with A$AP Rocky last week.

You can listen to the conversation with Al in the Projects I shared above or as a track here:

It makes sense that a nineteen-year-old like FearDorian would use [untitled] – mobile-first generation and all – but 20+ year industry veteran Al used it, too. That said something different.

[untitled] seemed to have weaved its way into the process of everything that night – to be fair, one of the reasons Stephen chose this show was that all three acts happened to be [untitled] users – but still, it was everywhere.

blair, the night’s headliner, had been on a five-year hiatus before dropping their new album. Genny, blair’s lead singer, credited [untitled] with making the album happen, finally. Five years is a long time and a lot of pressure. There were so many tracks to choose from, from which to assemble an album worthy of the wait. [untitled], he said, made choosing and organizing happen.

Stephen, an artist and sound engineer himself, recorded the whole show on [untitled], so that he could take it home, split the stems with [untitled]’s stem splitting AI, and mix it into his own track.

[untitled] started with storing, organizing, and sharing. It’s added light editing features and stem splitting.

It’s becoming a part of more and more artists’ workflows, beyond Bushwick.

Tommy Richman made Million Dollar Baby with [untitled]. The song peaked at #1, which is as high as a song can peak, mathematically. There’s a good chance it’s been stuck in the very same brain you’re using to read this piece, and if it hasn’t yet, here you go:

The more artists that join, the more artists join. One, because people want to use the tools that their favorite artists are using. More directly, because when artists use [untitled], their collaborators use [untitled]. One artist’s producer might produce 15 other artists, each of whom have their own team of collaborators. Their fans use [untitled] too, to listen to links of work-in-progress tracks and albums.

And they share. Buddy Ross – he produces Frank Ocean, Bon Iver, and Travis Scott – shares snippets of the tracks he’s working on from [untitled] to Instagram Stories, while it’s still WIP. “The design of [untitled] really encourages people to share their ideas,” Stephen told me. “We even have a feature that lets people upload specific snippets within a song to social media.”

Dancho told me links to unreleased [untitled] tracks are becoming a currency of sort in music, like mixtapes back in the day or, to put it in context for me (a geriatric person), “like writing an angel check in a hot startup.” Artists can share snippets from [untitled] right to their Instagram Stories, little teasers to build the suspense.

[untitled] is a bit of an anomaly, a mobile product built in the 2020s that can somehow tap the benefits of building a mobile app a decade ago.

It’s getting real and sustained network effects, for example, in an era where real network effects are hard to come by and harder to sustain. To wit, [untitled] just crossed 10k paying subscribers and each month, over 100k musicians and their teammates use the product.

And it’s starting to own a workflow in an era when most of the good workflows are already owned.

Put differently, “mobile” shouldn’t be a “why now?” for a product built in the 2020s, but for [untitled], it has been.

Part of the reason, perhaps, is that AI is changing who can make music and how. That one isn’t quite right, though, because [untitled] started resonating with musicians before AI became a thing, and because its sole AI feature, stem splitting, lives in the background.

A bigger part of the reason, Dancho thinks, is that music is an industry with a weird relationship to software.

On one side, there’s software created by the software equivalent of indies, distribution platforms like DISTROKID or cdbaby and creator tools like Ableton plugins. Even Ableton itself, the most popular and beloved DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), has refused to take venture capital.

On the other, there are the big splashy products, the software equivalent of pop music, mercenaries with little care for the craft, or for the crafters.

There’s room in the middle, though, for a product built for both craft and scale, kind of like the Frank Ocean of software. Billions of listens on Spotify, but even music snobs like him. That’s what [untitled] is trying to be.

Like Frank Ocean, [untitled] defies easy categorization. It’s building something that works for mainstream artists and underground producers alike, something that both captures and expands the market. It's a balancing act rare in music software, where tools typically either cater to professional studio engineers with complex, feature-laden interfaces, or offer watered-down consumer versions that serious artists won't touch.

Ocean famously takes his time between releases, disappearing for years to perfect his work, then emerging with something that somehow exceeds the endless anticipation. The [untitled] team shares this obsession with craft - Dancho and José spent years iterating on the product until it felt right, initially frustrating investors who wanted faster deployment cycles. But like Ocean, when they finally shipped, they had built something artists fell in love with.

In an industry often forced to choose between artistic integrity and commercial success, [untitled] wants to achieve both. In a software landscape that’s been overplaybooked, [untitled] wants to craft a product that feels like art.

Dancho and José now have the $$$ to do that, to the tune of an $18 million Series A led by Anish Acharya and Olivia Moore at a16z.

Can you mix music and money? What about musicians and AI?

I guess it depends on who’s doing the mixing.

Dancho & José

Lisa Marie: “How did you two meet each other?”

Dancho: Well, we’ve known each other since before we were born. Sounds a bit ridiculous, but we come from a Mexican community that immigrated from Mexico City to San Diego. Our parents knew each other from Mexico City. Our great grandparents, actually, we found out recently, used to be friends, and they used to go to the park together. We became really close over the fact that we're both the youngest of three siblings. Our older brothers were a huge inspiration for us musically. All of our older brothers were really obsessed with music. They were even in bands together. His brother used to drive my brothers to the concerts in San Diego.

To add to that, we also grew up like eight minutes away from each other, and developed very similar interests. We were both obsessed with music, and then we both became obsessed with technology and Apple and all this stuff, and it just kind of happened beyond us in some ways. Someone else was dictating our relationship.

José: When I was in 9th grade, Dan came up to me, and he's like, “We should build an app.” And I said, “Yeah, I do want to build an app. I'm actually thinking of a project or whatever. And then Dan's like, “I'm thinking about a way to be able to create your own clothing, like a fashion app, where I can just put in my own design, and then get that clothing shipped to my house.” And I was like, “Yeah, that sounds like a really cool idea.” We just kind of kept chatting from there.

Dancho: That's the start of our book. That's the intro.

Good artists copy. Great artists steal. Lisa Marie interviewed Dan Lilienthal (Dancho) & José Chayet (José) in May for Big Ass Kids. Their answer there was good. Save it. Remix it. Add my own spin.

I first met Dancho & José almost three years ago to the day, on November 16, 2021, on an introduction from my friend Adam Besvinick, the first [untitled] investor and someone I’ve known since we went to rival high schools before ending up in the same freshman class at Duke.

Maybe he introduced us because Dancho went to Duke, too, and maybe it was because, but whatever the reason, it was a good intro. Dancho & José are clearly comfortable with each other, clearly have a vision, clearly care about musicians, and are clearly different than most founders I meet.

By that I mean, as a follow-up to the conversation, they sent:

“Also, here is a digital version of our zine where you’ll find our references to Marcel Duchamp!”

A few emails later, they wrote, “also here is the lofi tape our producer in Tijuana just released!”

An appreciation of Duchamp and a producer in Tijuana who makes Stevie Wonder lofi may be necessary to create tasteful music apps, but they probably are not sufficient. So in addition to those two attributes, Dancho & José got a more formal education, one at the greatest university in the world and sneaky unicorn factory, and the other at Penn, which is also good, while also making music themselves. When José graduated, he got a job in Product Management at Facebook. When Dan graduated, he didn’t want to get a job and wanted to build a company.

Somewhere during all of that, the idea for [untitled] was born out of their shared brain. Back to Lisa Marie (emphasis mine):

Lisa Marie: When did the idea for [untitled] first come into existence?

Dancho: As we said, we've been obsessed with technology since we were kids, and we've been obsessed with music since we were kids. By the time we were in college, we were working with startups. So that's kind of like what we were doing professionally. We were doing internships, doing all that stuff, just trying to break into the tech world. In parallel, we started getting re-obsessed with music now as not just consumers, but actually making music. During my sophomore year of college, José started making music and he started sending it to me, and I was like, “Damn, this is cool.”

He was making these awesome beats on his phone, and was sending them to me just for fun. I also started dabbling in making music on GarageBand. Around this time, José also introduced me to BROCKHAMPTON, who were a huge inspiration for us – seeing all these kids who were just making music in their bedroom.

Around the same time, we both had started to get some experience with helping out our friends who made music. My older brother is a musician, so I was helping him out with his group. As we got deeper into this world we became really frustrated with the tools that existed for that entire process. Especially coming from the startup world, we're so used to all these incredible productivity tools that exist for all these different industries. You have tools like Notion, you have tools like Figma, you have all these productivity tools. In music it just felt like there weren't really beautiful tools built to help artists nurture and maximize their creative process. We decided that we wanted to build a company that had that at the core of its mission. So we built [untitled].

José: I think Dan and I realized that music is a four dimensional form of communication. It's just a way of communicating between one person and another. Sometimes friends send each other music. It's easier than sending like a 30 sentence paragraph over text on how they're feeling. You could just send a song and then immediately understand how they’re feeling. We all tend to think about music as this thing that you release to the world, but in reality, there's a lot of music being sent just between close friends. In fact, if an artist is releasing maybe, let's say, ten albums over the course of their career, which is maybe like 100 - 200 songs, then they've definitely made over 10,000 songs. A lot of that music gets sent to just a few people, whether it's your mom, your significant other, whatever.

For musicians, I think there's this pressure for the music that's released on DSPs. In reality, the other 9000 tracks that you haven't released are very valuable. They have intrinsic value. They have the spiritual value of your emotions, of who you are as a person. Artists shouldn't feel like they are beholden to experiencing their music in a predefined way. Sometimes fully materializing a song is just sending it to your mom or sending it to your friend or sending it to your bandmates. Right now, the mainstream concept of fully materializing your music is putting it on Spotify or on Apple Music.

We saw this gap between the DAW and the DSPs. In the DAW, a song feels like it's still being worked on in terms of editing and production. On DSPs, it feels like it's already a finished product. We saw this space where you want your music to feel materialized without it being on a streaming service. When you bounce your music out of the DAW, where are you going to listen to it? A song doesn’t feel realized on the Files app and Dropbox. It feels like a random file. On [untitled], a song comes to life, and you can let it sit there without pressure.

Dan: It's really sad that for many artists pre-[untitled], they had to listen to their precious creation, their precious emotional output, on a product that does not really value it. Right? You put the song that you wrote after you were sad one evening because your girlfriend broke up with you on Dropbox or the Files app, and it literally just feels like any other file. It's sitting right next to this PDF that your boss sent you. It's like sitting right next to where my emotions are is this random PDF about my professional life. There isn't this sense of treating unreleased music sacredly. It's kind of bizarre that it's easier and more delightful to listen to someone else's song on Spotify than to one’s own music on whatever service you're using. [untitled] is designed to treat your unreleased music preciously, and be the best place to listen to it.

I’m sorry for the long quote, but it’s better you hear it from them directly. Those are not emotions I feel. I don’t make music. I grew up pre-Spotify, and when Spotify came out, it was magic. But they feel it, you can tell when you talk to them, that they really want to build something great for musicians and their teams, like really want to do that, and that means building a business, because to scale you need revenue and resources, but in a way that you don’t normally feel talking to people making tools for enterprise, the business, for Dancho & José is in service of the customers.

So José left his job and Dancho decided not to get one after college and the two – I’m sorry, I’m going to have to apologize for the second time in two paragraphs – got the band back together.

Thus came the tension that always comes for artists: you need money to create art.

Investing in Music

I’m being dramatic. Dancho & José felt no conflict. But they did need money.

So in late 2020, they started talking to investors, and by early 2021, they closed a $900k pre-seed from two investors: Niko Bonatsos at General Catalyst, who writes in his company bio, “My passion is working with first-time technology founders with strong product instincts” (✅, if you don’t count Squeezed, which is the aforementioned app the duo co-founded in 9th grade), and Adam Besvinick, at Looking Glass Capital, who I introduced you to earlier and who introduced me to Dancho & José.

At the time, Adam told me, his thesis was that “the fastest way to record any idea is speaking it. If [untitled] was the default way to record any idea, starting with music, that’s a powerful point of leverage for all sorts of other stuff.” Like me, Adam is not a musician, and he shared the app with a bunch of friends who aren’t musicians, and they all said, “Shit I’d use this. It’s way better than Apple Notes.”

Capturing ideas, running them through models (even the pre-GPT 2021 models), building more products on top of that data, suggesting other ideas, other things to explore… that was a big idea.

Hit pause. It doesn’t sound like a big idea from our perspective in late 2024. But [untitled] got started back in 2020, raised money in early 2021. This was a different time. Bring yourself back there for a second, locked down, stuck inside, on Clubhouse.

Clubhouse was The Big Thing. As [untitled] went out to raise $900k, the digital ink was just being put to digital paper on Clubhouse’s a16z-led $100 million Series B. “Synchronous audio was blowing up,” Dancho told me. “We didn’t think it would be a thing. But asynchronous audio…” Asynchronous audio – all asynchronous audio, in one easy to use app – that was something that, at the very least, investors could get behind, something that could fund the music.

So from the investor perspective, music was the starting point, a niche market with a passionate user base and a clear need, en route to all asynchronous audio.

But for Dancho & José, it’s always been all about music.

They raised their $3.7 million Seed round in early 2022, led by Niko at GC alongside Mo Koyfman at Shine Capital. Mo, like Niko, has a thesis that [untitled] fits to a T.

I’ll tell you more about this one, at the end.

The Seed is the round I participated in through Not Boring Capital. When I met them, the idea was all about music. “They never moved outside of music,” Adam said, because they didn’t have to.

They put their WIP track, as it were, in the hands of artists, and artists led them deeper into music. Specifically, listening to it.

“At Seed or right after, they found a killer use case – listening,” Adam told me. “Playback was the unlock for them.”

Instead of just capturing music when inspiration struck, musicians could also listen to their music, whether captured in the app or exported from their DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), and play it for other people: friends, producers, collaborators.

Sharing is big, but even just playing it for themselves is big. Ethan Daly, who works with Mo at Shine, thinks [untitled] potentially increases artists’ consumptive behavior. “Most musicians' favorite artist is themself and they love listening to their own music pre-release (this changes drastically once a song is out),” he told me, from experience. “I've even found myself listening to songs I'm working on 10x, 20x, 30x+ a day, both out of enjoyment and to make passive improvements, which I add to my track notes.”

There is an ownership and obsession bestowed upon a song when you make it that I aggressively compare to having a child.

“Can’t they just listen to their baby on Soundcloud or Spotify?” you might be asking. But these are WIP tracks, not ready for prime time. And continuous playback isn’t readily available in other storage products, which weren’t designed for music. Listening is clunky there, and you definitely can’t edit and take notes while you listen there, like you can in [untitled].

Playback was a hint that they were building something deeper, the glimmer of a full-stack music workflow product.

Listening went up every month, without much marketing, through Word of Mouth. “Oh shit,” Adam recalled thinking, “You’re seeing people using the product this way more than my original hypothesis.”

Then, the next question, maybe the question that so many investors have asked and answered that there’s still an opportunity to make a mobile app (!) for musicians (!) in 2024 (!):

“If this is just a music thing, how big can it get?”

The Music (Software) Business

Music software can be split into two categories:

Consumption

Creation

“Distribution is a third, in my opinion,” José told me, “However, on platforms where creation and consumption are both available and tightly coupled… distribution collapses.”

When I asked Dancho whether there actually was a Why Now for [untitled], he said there wasn’t a big technological one – “this probably could have come out any time post-iPhone” – but there actually is a business model one, about the interplay between consumption and creation.

And it goes a little something like this…

Napster came out in 1999 and set off a dramatic decline in the music industry’s revenue as consumption shifted from CDs – which cost ~$18 and bundled songs you wanted with a bunch of others you had to pay for to get the ones you wanted – to downloads - which were free and a la carte. Even iTunes, which let you buy singles for $0.99, couldn’t make up for the gap, particularly when, even after the death of Napster, other free download services popped up to replace it. Free is hard to compete with.

This was a crisis for the music industry and, in Dancho’s telling, meant all-hands-on-deck focus on fixing revenue, which meant fixing consumption. Or, as Dancho colorfully summed it up, “Music is digital, people are ripping it, how the fuck do we make money?”

New digital creation tools sprung up, too, DAWs like Ableton (2001) and Apple GarageBand (2004), the only two of the top six most-used DAWs created this millennium. Both were created in the beginning of the downtrend, when new digital technologies meant new ways to help artists create but before it became clear that other new technologies would mean that whatever they created, there might not be any market to sell to.

So first: get the money, without which DAWs would remain hobbyist tools. In other words, there was little appetite among the most talented entrepreneurs to build tools for an industry with declining revenues and no end in sight. Imagine the pitch:

“We are disrupting the $500 million (and declining) music creation industry to serve the $10 billion (and declining) music industry!”

And for that reason, I’m out.

Then came Spotify. Founded in 2006, launched in Sweden in 2008, came to America in 2011. Spotify was a miracle. I still remember the first time I used it. Every song. On-demand. Right on my phone. Free is really hard to compete with, but if there’s one thing that can compete with free, it’s convenient. For $9.99 a month, I didn’t have to go to Kazaa or Limewire, find a track, find a version I could download, hope it wasn’t corrupted, hope it didn’t give my computer a virus, or transfer it from my computer to my phone. I didn’t have to pay $1 per track to iTunes. Anywhere I was, I could just search and hit play.

You all know the Spotify story, so I won’t repeat it, but the punchline is: it worked. The recorded music industry’s revenue actually started growing again.

Spotify solved consumption to the tune of a $92B market cap. It’s how people listen to, and pay for, music.

Spotify figured out how the fuck to make money. Last year, Spotify made about $14 billion and it paid out about $9 billion in royalties to artists, labels, and others in the industry.

That is more than the entire US recorded music industry made in 2014 or 2015. Powered by DSPs (Digital Streaming Platform) like Spotify and Apple Music, the music industry is growing again, not back to its 1999 peak quite yet, but on its way there.

In 2023, the US recorded music industry made $17.1 billion. Globally, recorded music made $28.6 billion, higher than 1999 (if not adjusted for inflation).

While the record industry’s revenues sank and stagnated, Anish said, there was “a vacuum of founders with the courage to build in music.”

“Now that that’s been solved,” Dancho concluded, “artists realize they can make money off their music, they want to create, and no one’s focused on creation.”

And that is Why Now.

Still, though, music creation software is not a massive industry. According to MIDiA, “Music software, sounds and services generated $884 million in 2019 with Plugins and VSTs the largest single segment (43%).” It’s growing, but it’s not the massive market that makes investors bop.

Which is why it made sense, if you were Dancho & José to pitch all audio, even if you knew you were going to be music, even if you knew you wanted to be all music creation, eventually.

That didn’t even seem like something that was really possible to do in an app. “I didn’t see them pursuing the mobile product as deeply as they have, it wasn’t clear that could all get built elegantly into a mobile product,” Adam told me. “If I’d thought that, I would have been comfortable never going outside of music. It just wasn’t on the roadmap. It wasn’t clear to them or me that it was even technically possible.”

But it actually might be.

Turning DAWs Into an App

There’s that commercial that Apple got a lot of heat for, the one Steve never would have made, that shows a hydraulic press crunching dozens of physical tools and instruments into one thin little iPad Pro:

That’s kind of what [untitled] wants to do for music creation tools.

The fun thing about knowing a company for a while is that you can see the evolution, from a time when an idea might live as a dream not solid enough to put into a deck to the point where it becomes clear that it is.

See if you can notice it.

Here’s the [untitled] Seed Deck:

And here’s the [untitled] Series A deck, the one they whipped together quickly after Anish and Olivia at a16z came to them interested to learn more:

Did you catch it? Same picture, different message.

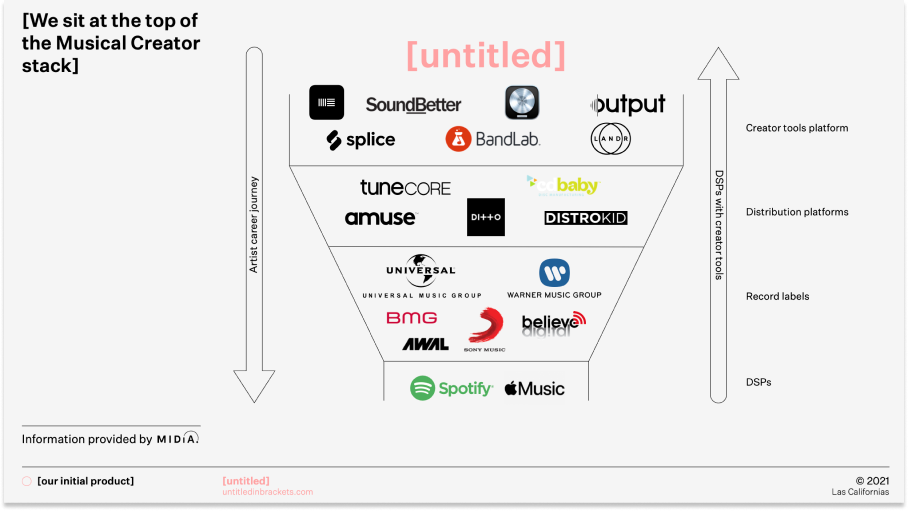

At the Seed, [untitled] said they planned to sit atop the Musical Creator stack, the lightweight, mobile entry point into a fragmented world of DAWs, distribution platforms, labels, and DSPs.

By the Series A two and a half years later, [untitled] said they planned to eat the whole thing.

As Anish wrote simply in the blog post announcing a16z’s investment, “Enter [untitled], which is building the new operating system for musicians.”

I’m making it sound like there’s been a lot of back and forth in the vision, but that’s not true.

Dancho told me, “We’ve always had this vision of being Amazon Prime for music: one subscription for everything. Musicians are stingy. You need to offer them a lot for their money. We hope that in the future all an artist needs is [untitled] and their creativity”

But there’s been a subtle evolution in the way that Dancho & José have explained their vision to both investors and musicians.

At the Seed, they just needed to prove to musicians that they were the best place to start, store, and share WIP tracks, and they needed to prove to investors that musicians recognized that they were that place. Mission – while still, always, a WIP – accomplished.

The plan was to get that usage from musicians, then turn those numbers into charts to prove to investors that musicians loved the app, to get the money to go out and build deeper into the Music OS stack, like that hydraulic press, slowly crunching the fragmented landscape of music tools into one app.

Then something even better happened.

Olivia said that the firm met Dancho & José in early 2021, had been following it since, and started to see the website and app pick up a lot of steam in the external data, which piqued her interest.

What got her even more interested, though, were the pings.

a16z has a Cultural Leadership Fund whose mission is “Connecting the world’s greatest cultural leaders to the best new technology companies.” Specifically, the fund’s LPs consist of Black artists, athletes, and leaders including Pharrell Williams, The Weekend, Lionel Richie, Kevin Durant, Patrick Mahomes, Shonda Rhimes, Chance the Rapper, Will Smith and Jada Pinkett, Quincy Jones, and Nas.

“The bar for non-professional investors to notice a product, then notice that it’s a startup, then reach out,” she said, “is high. But we started getting pings from professional artists telling us that [untitled] was the next big thing in music.”

See what I mean? Isn’t that way better than just showing an investor that artists use your product with a graph?

Based on the pings and the data, Anish and Olivia reached out to reopen the conversation with Dancho & José this spring. It was a good conversation, but a16z initially passed.

Then Anish, a musician himself, spent more time on the app. And he was blown away.

“I spend a lot of time obsessing on products and product details. Most companies have one big insight and a lot of little things supporting that,” he explained. “This one is unusual because there are 30 insights. I’d text the guys ‘It would be amazing if you could do this,’ and they already had.”

Anish kept playing. He discovered someone who put an [untitled] track on twitter, started using it from the consumption perspective, and it was a totally different consumption experience than anything he’d had.

“The playlist is such a disappointing atomic unit,” Anish thinks. “They suck. [untitled] is something else that allows you to play around in a different way.” More mixtape than playlist, but still, a different, third thing.

As a musician, he took one of his tracks and threw it on [untitled]: “I dropped the track in, shared it with a few people. I could do stem separation, one swipe away.” Here. I’ll share it with you, too. I’ve been writing to it since he sent it to me.

“It was the shortest path from inspiration to output that I’ve ever seen,” he noted.

While all of this was happening, Dancho & José thought the a16z deal was dead, because a16z said they wanted to see more game film. It was fine – they weren’t raising, they didn’t need the money – they just didn’t think it was happening.

“A few days after they passed – 12 days after that,” Dancho recounted:

We get an email from Anish saying, something like, “Hey guys, I’ve been using your app for the past week, I’m obsessed, want to make something happen.” He fully apologized. “I’ve never done this where I passed and wanted to make something happen, but I’m in love with your app and want to make something happen.”

Then he made something happen. a16z led an $18 million Series A.

Which is a fun thing to be able to say about a portfolio company, but really, is the money Dancho, José, and their absurdly small 7-person team need to start building down the stack.

Because sitting at the “top of the Musical Creator Stack” is just the right entry point to go further down, to “vertically integrate the entire music stack for artists.”

Remember, though, when Adam said that it wasn’t clear if that was even technically possible?

“You need to ask them to see the latest design,” he told me. “It’s an extremely feature-rich product designed in a way that doesn’t feel overwhelming at all. I don’t know how they’ve done it.”

Of course, Adam is an [untitled] investor. He’s supposed to say nice things for public consumption. But he also said it wasn’t always like this.

“There was a long period where it was extremely frustrating,” he told me. “They treated the product like a Faberge Egg that they didn’t want to break. They didn’t want to get it into the hands of users to tell them it sucked.” Adam, Mo, and Niko had to push Dancho & José into the deep end: “You need to ship faster and you need to get user feedback in tighter loops because development cycles aren’t happening quickly enough.”

There’s always that tension, in music, between art and capital. The artist wants it to be perfect. The capitalist wants it to make money. It’s clear talking to Dancho & José, and hearing these stories, that they lean artist. Which is probably why the product is so damn good in an age when most apps kind of suck.

But once again, you need money to make the art, and you need crowds to tell you if it’s any good.

So they listened. This is the back half of 2023. And they put the product in musicians’ hands, afraid that they were going to have their feelings hurt, and … they didn’t. Musicians loved it. They realized they built something that people actually wanted, lots of people. They combined the artists’ sensitivity with the capitalists’ speed, and tightened that craft, ship, iterate loop, and that’s why, in the spring of 2024, the product was growing fast enough and gaining enough popularity – even among the big time artists backing the Cultural Leadership Fund – that a16z took notice and wrote them a check.

Which is why they can build more of the OS, now, which Dancho showed me the other day.

The Operating System for Music

“We’re not ready to show this to a lot of people yet,” Dancho warned, “but I’ll show you what we have.”

Describing the app in words is, at best, like trying to get you to appreciate a song by reading you the lyrics in monotone. Maybe I’ll start with some OS philosophy, which does work in words.

“If you think about an Operating System” – this is how Dancho started the demo, and I think gives a hint as to why this team is so good at product – “It has a bunch of different apps that do the different things you need.”

The beauty of an OS is that

If I don’t need something

It’s not in the way.

Philosophically,

That’s what we wanted to achieve

Adding more creative tools.

Offering a lot of tools

While keeping the app simple

So the tool doesn’t get in the way

When you don’t need it.

DAWs have a lot.

They’re overwhelming.

We want to be

Powerful

Yet simple

At the same time.

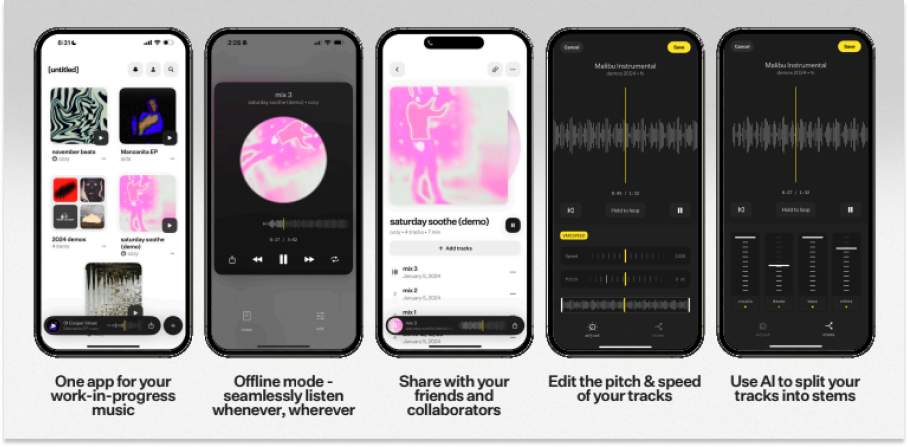

Then he showed me. It’s like three little apps: Notes, Edit, Record.

Notes: to write down lyrics, jot down ideas for collaborators and fans.

Record: self-explanatory. Hit the red button, sing, strum, bang, whatever.

Edit: AI-powered stem splitting, plus the human-powered tools you’d expect, like pitch & speed.

It’s all there

Flexible, fluid

You can jump around

In the edit suite.

The creative process

Is fluid

So you want easy access

When the idea hits you.

From there, you can share. Share with collaborators, share with fans, share to Instagram.

I can show you what some of it looks like today, the released and polished version that lives on their website, so you get a flavor. Here:

And here:

And here:

But really, you should just download it and play around for yourself. Here’s the app (you might notice the 4.8 star rating on 3.5k ratings while you’re there).

You’ll notice that it doesn’t look or feel like this:

It will never look or feel like that, because as great as Ableton is, it wasn’t designed for mobile, it wasn’t designed to be there at the spark, to be with you whenever inspiration strikes, and, increasingly, to stay with you, wherever you and your track go, until you’re ready to share your WIP with some people and hope they don’t crack it.

That’s how [untitled] plans to move down the stack, to vertically integrate. Be there at the beginning, then keep building tools – apps within the app – to help musicians and their teams do more and more.

But how, exactly?

The [untitled] OS Arrangement

Starting at the beginning is a good place to start.

The first movement in the arrangement is to be there in the beginning. As it stands, “[untitled] is a sacred place for artists to listen, edit, share, and organize their work-in-progress music.”

When you have an idea, you jot down lyrics or hum a bar into [untitled]. When you have a track you want to share and collaborate on, you store it and share it with [untitled].

That was it, for a while, the whole thing, the thing that people like FearDorian and Al Carlson use [untitled] for today. Phase I.

The second movement is underway now, with the edit tools – pitch and speed, AI stem splitting – that are already in the app, and the ones that Dancho previewed for me coming soon.

But artists need so much more to turn something WIP into something final, something they’re ready to share with the whole world.

And that – 6,000 words in – is where we talk about AI.

Chances are, you’ve played around with AI music generators, or at least listened to tracks other people made just by prompting. If you haven’t, you should check out Suno and Udio.

Udio raised $10 million. Suno has raised $125 million and is valued at half a billion dollars.

These represent one view of the future of music, one in which anyone with a good idea can create songs with a few words. In this view, the AI replaces the artist, or at least changes what constitutes the artists’ skill.

[untitled] has a different view of the future, one in which AI adds new tools to the musician’s toolkit, and makes it possible to squeeze more power into one simple app.

One of the benefits of being the sacred place for artists to store their music is that you end up building a very large repository of unreleased music on which to train (appropriately permissioned, of course). Better, for each artist, it’s a catalog of their own process, which could power personalized models.

With a dataset like that, and open source software like demucs from Meta for stem splitting and Whisper v3 for lyric transcription you could build tools for musicians unlike anything they’ve used before. Some ideas:

Generative lyrics: using lyrics I wrote, generate vocals trained on my other songs on top of this new instrumental.

Generative guitar samples: generate 10 punk guitar samples that I could use for this song.

Generative drum samples: give me a drum sample similar to the one I did on that other track, but sped up to 96 bpm.

Generative chords: help me generate a chord progression I’ve never tried before.

Generative albums: take this album I made and make it more hip hop.

Generative band: throw a band behind these vocals.

These tools will be powerful and personalized. Generate vocals that sound like me. Give me a drum sample like I did before but faster. Help produce my track. And they’ll all fit inside a button: start talking to create and edit.

This will expand what musicians can create and who can create music. I can write a little bit and sing a little bit, but I can’t play any instruments. So I could just sing and ask [untitled] to fill in the rest.

From the perspective of vertically integrating the stack, this is important because it means that entire songs can be created within the app. Then, distribution can be as easy as hitting another button, one that says “Share Track with My Fans” or “Push to the DSPs.” This is where [untitled] might start competing with the DistroKid and CDBabys of the world, who exist to make it easy for artists to distribute their tracks to all of the DSPs – Spotify, Apple, Amazon, Tidal, TikTok, YouTube, and more – all at once.

But I think something more interesting happens than simply replacing existing distribution channels. I think [untitled] creates new types of distribution, new “atomic units” for music.

“This is because technology not only enables content categories, it defines their business models and shapes the content, too. And as we know, technology is in a constant process of change.”

Shaping Content

That last quote is from Matthew Ball, who wrote How Technology Shapes Content and Business Models (Or Audio’s Opportunity) back in October 2020.

If you’ve gotten this far in the piece, you should read that one, because it’s a really fascinating exposition of how the defining music technologies and business models of an era shape the music that gets made. One telling anecdote: songs have gotten shorter in recent years (the chart on the left) for a very specific reason:

To support engagement-based monetization, Spotify and its label suppliers had to define engagement. And they chose to do this on a per stream basis with a minimum stream time of 30 seconds (to avoid accidental plays, track skipping, etc.). However, this meant that a 10-minute track, five-minute track and 31-second track generated the same royalties.

Even better, the same listener can listen to your two-minute song two times in four minutes, but can only listen to your four-minute song once in four minutes. So shorter songs get more plays, and therefore higher rankings on the charts and more revenue. This, Ball explains, is one of the reasons Lil Nas X’s 1:53 Old Town Road was the top track of 2019.

If [untitled] succeeds, what might the new model look like?

The way that Dancho & José see it, making it easier to share and discover WIP tracks is a way for artists to test their music, and fans to find new music, en route to the traditional path to labels and DSPs. Sharing and getting feedback, in this scenario, means that artists are more likely to release polished final tracks that appeal to their fans, who will consume where they currently consume, on Spotify or TikTok. And that may be the case.

But I wonder if that vision of the future is less radical than the one that might come to pass.

Ethan at Shine told me that while social sharing for both professional musicians and novices might feel like a stepping stone to the DSPs, “many users prefer to end the journey here rather than watching their music get lost in the shuffle of streaming platforms and monthly listener counts dwindling to zero.”

There’s a version of the [untitled] discography – not yet fully created, still to come – in which the company shakes up the music industry more than even its founders are willing to dream. To pick up the faint sounds of that future, we’re going to have to flip to the B-Side.

B-Side: Strategic Analysis

If you view the music industry as something frozen in amber in the early 2000s, then you might expect that now, now that people are building tools for music creators again, the industry may speedrun the changes that have taken place to most other industries whose products could be digitized.

In Vertical Integrators, I talked about why there won’t be any more Aggregators:

The short version is that Aggregators had already won the biggest categories that were susceptible to Aggregators, and that the remaining categories were too small to support the necessary model: spend a lot upfront, and make it back on small margin dollars over a huge amount of transactions.

One addition to that hypothesis is that Aggregators worked for categories that were either digital – and therefore where marginal costs for new supply was practically zero – or where supply already existed, like cars or homes. Better allocating those existing resources was a coordination problem – an information problem – and therefore susceptible to Aggregators.

The more I think about it, the more I think music might prove me wrong.

Music is a funny category from the perspective of Aggregators. In 2017’s The Great Unbundling, Ben Thompson wrote that the music industry had surprisingly ended up in pretty good shape, ultimately and ironically undisrupted by the internet:

While piracy drove the music labels into the arms of Apple, which unbundled the album into the song, streaming has rewarded the integration of back catalogs and new music with bundle economics: more and more users are willing to pay $10/month for access to everything, significantly increasing the average revenue per customer. The result is an industry that looks remarkably similar to the pre-Internet era:

Notice how little power Spotify and Apple Music have; neither has a sufficient user base to attract suppliers (artists) based on pure economics, in part because they don’t have access to back catalogs. Unlike newspapers, music labels built an integration that transcends distribution.

Back then, he didn’t think of Spotify as an Aggregator because it had to pay so much of its margin to the record labels. It had failed to commoditize the labels.

In 2022’s Spotify, Netflix, and Aggregation, Thompson changes his mind, arguing that while Spotify hadn’t made content acquisition free, it had commoditized content and shifted the power from owning supply to owning demand. In a world of abundant, zero-distribution-cost music, controlling the “best means to surface the content users want” is a valuable place to sit. Spotify started to put a price on that value, Thompson noted, in the form of “promotion,” or advertising.

Spotify, he realized, was more of an Aggregator than he thought.

What’s interesting about other Aggregators – particularly Level 3 Aggregators with zero supply costs like Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube – didn’t just change the nature of supply, they changed what supply looked like and who could be a supplier.

Twitter, for example, didn’t just aggregate news stories from professional journalists, it turned anyone into a kind of micro-journalist. It made it really easy to get your written thoughts in front of a large audience and expanded the pool of people who could do so.

Ditto Google and Facebook, both of which aggregated traditional journalism as it moved online, but both of which enabled new types of content and new types of content creators.

With Google, any coder in a garage could spin up a website – a new form of content – and let the world find it. With Facebook, your crazy uncle’s deranged political takes – an age-old but newly digitized form of content – appeared in the same feed as stories from The New York Times and pictures from your friend’s party last night.

With Instagram, everyone became a photographer. With TikTok, anyone could make short-form videos.

Think about YouTube – think about the vast diversity of content on the platform compared to the content that a major studio would release in theaters or on TV.

Spotify, while changing music’s distribution and business model, and while incentivizing a move back towards shorter songs, didn’t fundamentally change the “atomic unit” of supply, to steal Anish’s phrase.

[untitled], in the mega-bull case, has the opportunity to do just that.

The [untitled] Mega-Bull Case

First, once it adds AI creation tools, [untitled] changes who can make music and what they can make.

A talented guitarist doesn’t have to join a band and be a bit player in the lead singer’s show. She can play guitar and fill in an orchestra, even vocalists, behind her. I can write some lyrics, sing into [untitled], and back myself up with a digital band, tell it to sound a little more like Daft Punk, a little less like ABBA, or whatever.

Traditional musicians – the ones releasing albums on all of the DSPs today – expand what they can make and how much they can make.

So second, just like there are many more tweets than there are articles in newspapers, there will be many more songs than there are on Spotify.

Many of them will make their way to Spotify and the other DSPs, but I’d imagine many of them won’t. They might be shared on other platforms like TikTok, Instagram, or Twitter, in group chats with a small number of friends, or custom made for that special someone in a special moment.

Third, exactly what that atomic unit is changes.

It might not be the song itself, or an album, or a playlist, but a journey – all of the versions, cover arts, notes, that go into making a song.

This is all speculation – Dancho & José haven’t said this is where the product is heading – but I think there’s a world in which listeners subscribe to artists and get the full stream of what they’re working on: the WIP tracks, the completed tracks, the notes. Maybe they can take tracks and split them, remix them, release their own. Maybe there’s some attribution that pays out the original artist when their track is split, remixed, released, and paid for.

“We believe creation is a higher form of consumption and expect more and more consumers to demand these types of experiences in the future,” Ethan at Shine told me. And that while consumption on streaming platforms might not increase with more creation – we only have two ears, and they only have so many hours in a day – “Our bet is that democratizing access to the creative process will increase the population of "music creators" (many of which never make it to DSPs) and [untitled] will be able to directly monetize the full spectrum of consumers interested in music - ranging from fans, to novice beatmakers, to superstars - through premium tools and access to musical artifacts.”

[untitled] is the first investment that Shine has made against its two-year-old thesis – Mo and I had our call right after I wrote this last section, so if I’m crazy, Mo’s crazy too – that consumer was going to make a comeback, in a different form.

That it was going to be about reestablishing meaning as an important vector. “Music,” he said, “is the most fundamentally unifying creative type.” That these platforms would start out single-player – like [untitled] has – earn stickiness by providing a lot of value, and then grow out in concentric circles, growing out from the artist at the core.

The atomic unit becomes the artist, or the process, or something – the way that more people are paying for individual Substacks because they just want to read whatever that person writes.

What happens to the labels in this world? Does [untitled] replace them?

Maybe they survive, but become less relevant, the way newspaper publishers have survived, but become less relevant. They still own valuable back catalogs at the very least. But think about what a label does:

Financing: not as important when the cost to create and distribute trends towards $7.99 per month.

A&R: not as important when music becomes networked, when anyone with taste can be a scout.

Production: not as important when more of that happens in the app.

Album creation: not as important if the album is no longer an atomic unit, and the fans can give their input on what the artist makes directly.

Marketing & Promotion: not as important, again, if it’s networked. I don’t pay someone to market and promote my newsletters or tweets.

Distribution: not as important when you can distribute to DSPs at the push of a button.

Business management: not as important if software can handle payouts.

Tour support and merch: probably gets unbundled.

Industry connections: not as important when you’re going direct.

I’m painting an extreme version of this future. A lot of these functions will still have value. People have been incorrectly predicting the end of labels for a long time. But I really do think a lot changes when the nature of who creates and what they create does.

Besides, Frank Ocean doesn’t work with a label. He released Blonde through his own just a few days after fulfilling and ending his contractual obligations with Def Jam/Universal in 2016, and that’s worked out just fine.

Just how much of this new future [untitled] wants to or can build itself is an open question, but if they’re successful in changing how artists create, they’re questions that will need to be answered.

WIP

It’s probably appropriate that they don’t have the answers. [untitled] is a sacred place for works-in-progress, after all.

What I can say for sure though is that this feels fun. It feels like a throwback to a time – like 10 or 15 years ago – when you could just make an app and put it in peoples’ hands and see what they did with it.

It’s a weird accident of history that there’s an opportunity to build a consumer app in a big category that matters, like music, and it seems as if by building that app, Dancho & José have brought some of that 2010 vibe into 2024.

What I experienced at Elsewhere that night is exactly the kind of thing you want to experience around an app, the kind of thing you did experience before building apps became playbooked and commoditized and boring. You want a small niche of passionate users to tell other people in their niche that they have to try this new app. You want people to trade WIP tracks like a currency of sorts, like mix tapes back in the day. You want the thing to feel a little edgy – but polished – like being a fan of the band before they got big.

That trade-off – maintaining your cool as you grow and get more popular – is another one that artists have struggled with as long as there have been artists. It’s one that [untitled] will have to face, too, as they get more popular, make more money, add more power to their simple app.

I think it’s one they’re uniquely suited to figuring out, as artists slash technologists, and not the other way around.

Theirs is a vision of the future I want to see exist: one in which more people are creators, in which people create, share, and remix in conversation with each other. Certainly, one in which AI doesn’t replace artists, just gives them superpowers, the kind of world people say they want in some indefinite way but that Dancho & José have a definite opinion on how to bring about.

Personally, there’s this barbell of companies I want to see exist in the world.

On the one side are the Vertical Integrators, the companies building big, difficult things in the physical world to create the conditions for abundance, prosperity, and freedom, companies that help humanity live longer and richer. I write a lot about those.

On the other side are companies that make all of that living more fulfilling. The ones that answer the question: if we really do build machines that let us work less, what are we going to do with ourselves?

There’s a lot of work between now and that future, hours after hours spent sweating the details, getting the product just right for a small group of artists who will tell other artists who will spread the word to the world. From Elsewhere to everywhere.

The art they’re making is unfinished – it might always be unfinished – but what [untitled] is belting at the top of its lungs is that there’s a lot of value in the process.

Thanks to Claude for editing, and to Dancho, José, Stephen, Dorian, Al, Anish, Olivia, Adam, Mo, and Ethan for your input!

That’s all for today. If you have a little time, check out Speakeasy and of course, start creating with [untitled] or just go work there. We’ll be back in your inbox with a Weekly Dose on Friday.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

such a cool read thank you for that - I am curious how copyright plays into the thinking here. It feels like an important thing to get right at the beginning of a new modality of creation.

dope read and shouts to the squad 👏

the era of mass music creation is just getting started