The Venezuela Opportunity

A Co-Written Essay with Ross Garlick

Welcome to the 1,422 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 258,248 smart, curious folks by subscribing here (and go paid for more of the good stuff)

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday! We’re back with our second cossay, on a very different topic from our first on robots, but unified by the same question: What will it take to build things in the West?

One of my goals in co-writing essays is to share the unique insights and earned perspectives that I get to hear from people who learn by doing.

For example, one Friday morning in late October, in the midst of President Trump’s verbal escalation in Venezuela, I sat outside of a small cafe in Mexico City having breakfast with Forrest Heath III and Ross Garlick, the CEO and CFO, respectively, of our Colombian portfolio company, Somos Internet. We were in Mexico City for an Arc conference on building in Latin America during which Forrest and I hosted a salon on the potential for the region to be a strong energy and manufacturing partner to the United States.

During that breakfast, after niceties and microPOP logistics (you could actually, Ross said, rent space in restaurants or empty retail to serve as the mini-data-centers on which Somos’ active ethernet network relies), we started talking about Venezuela. What did they think, as people building a business next door, about potential U.S. intervention? Was it a big risk?

The conversation that we had from there, and a couple we’ve had since, have surprised me. They were more optimistic about the situation and about America’s role in it than I was. The people they’d spoken with in Venezuela told them that they all wanted Maduro out, they said, but that if any of them defected, they would be targeted and potentially killed. The U.S.’s presence might be able to break that impasse.

Their ideas were the first I thought of when the news that the U.S. had dropped into Venezuela and taken Maduro into custody on January 3, 2026 in Operation Absolute Resolve. I felt lucky to have a different perspective on the situation than the ones I was reading, not the One Final and Correct Perspective, but a differentiated one based on specific experience.

So I asked Ross to co-write an essay with me on what could go right in Venezuela.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Framer

Framer gives designers superpowers.

Framer is the design-first, no-code website builder that lets anyone ship a production-ready site in minutes. Whether you’re starting with a template or a blank canvas, Framer gives you total creative control with no coding required. Add animations, localize with one click, and collaborate in real-time with your whole team. You can even A/B test and track clicks with built-in analytics.

Say thanks to Framer by building yourself a little online world without hiring a developer.

Launch for free at Framer dot com. Use code NOTBORING for a free month on Framer Pro.

The Venezuela Opportunity

A Co-Written Essay with Ross Garlick

I like to say that living in Colombia is a long-term arbitrage.

I have never been to a place with a larger delta between external perception and internal reality, and I’m the beneficiary of getting in “early” and witnessing the world wake up to the truth.

I grew up in England, moved to the States for university, stayed to work in finance, quit to start a café in Bogotá, and moved to Medellín to become the CFO at Somos Internet, which many of you now know about thanks to Cable Caballero. Colombia is home. My wife and I recently got married here. We love it here. We plan to make our lives here. So it brings me no great pleasure to say what I’m about to say.

Venezuela has even more potential than Colombia.

A lot of people have become familiar with Venezuela over the past few weeks, since Operation Absolute Resolve, in which the United States captured Maduro and shipped him to Brooklyn. Many are trying to understand the implications for Venezuela, the region, and the United States. I’ve seen emotions from my friends and online bubbles that range from full blown catharsis to a cynicism that nothing substantive has actually changed.

I’m excited about it. Operation Absolute Resolve has created more open and exciting possible outcomes for Venezuela than any other event in my eight years in the region.

That said, in order to reap the country’s full benefits, people need to get excited about the right thing.

Oil is the obvious prize. But it’s a complicated one. President Trump asserts that selling oil from Venezuela is “gonna make a lot of money,” and it is true that Venezuela’s 304B barrels of reserves are the world’s largest. Until recently, more than 80% of its oil exports went to China. Redirecting the flow of Venezuelan oil would hamper Chinese road building and cut off 50% of Cuba’s oil supply, while giving America cleaner access to (very heavy, harder to refine) oil. Realignment could be as big a geopolitical win as a financial windfall.

As it stands, DOE Secretary Chris Wright has indicated that the U.S. will control Venezuela’s oil “indefinitely,” and, as it stands, that seems to be the biggest win to come from Maduro’s capture.

But oil isn’t the only prize in Venezuela. It’s not even the biggest.

We must rebuild and reopen Venezuela because it’s the most underpriced opportunity on Earth.

I’ll start with a caveat. This is a longshot opportunity that requires us to ask ourselves: “What is possible if things go right?” That’s one of the questions we’ve also been asking as we at Somos evaluate the Venezuelan market, and talk to people on the ground. During one of those conversations, a journalist friend told me, “There’s a long way to go and a lot of things have to go right for your vision to come true.” He’s right.

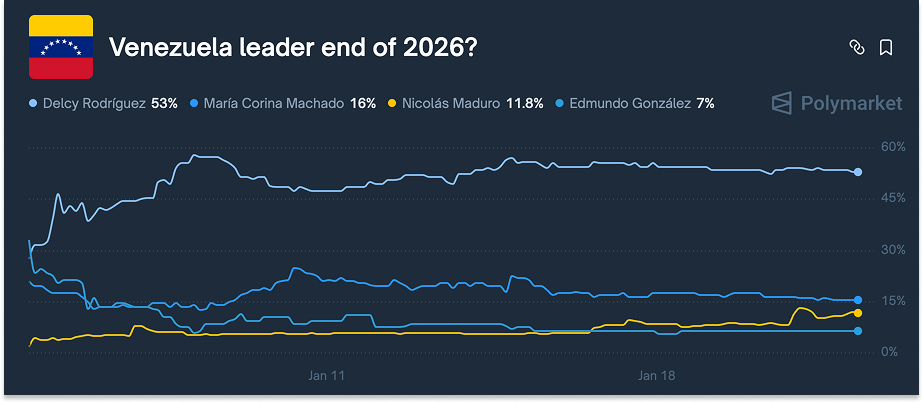

To start, a transition is not actually guaranteed. Prediction markets expect Delcy Rodríguez, the longtime Chavista official serving as interim President, to remain in power throughout the year.

I wouldn’t bet against those odds, but this market resolves at the end of 2026 and Marco Rubio has said that the US has a three-step plan for Venezuela: stability, recovery, and then transition, a plan that will undoubtedly take time to fulfill.

For this exercise, let’s say we do get a U.S.-aligned, freely and fairly elected transition government by year end 2027.

Well executed, with a free and democratic Venezuela, the Gran Colombia bloc of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador could become as strategically important to the U.S. as the EU or Mexico is within 25 years.

For context: Mexico is now America’s largest trading partner at $840B annually, supporting 5-6M U.S. jobs. The U.S.-EU relationship totals $1.5T in trade and $5T in mutual investment, supporting 5.7M American jobs. A Gran Colombia bloc with 105M+ people and $700B+ in GDP could eventually approach these scales, particularly if the country becomes a nearshoring destination for supply chains for which the US currently depends on Asia. It has the mineral resources, talent, and strategic location to offer what Mexico and the EU already provide to the U.S.: a large, proximate, culturally-aligned economy where American investment creates American jobs and reduces American vulnerability to rivals.

This potential future is why it’s worth it for the United States to help rebuild and reform the country’s institutions instead of calling Maduro’s capture a victory, grabbing the oil via an uneasy truce with the remaining Chavistas, and moving on to the next conquest.

Importantly, doing so will help the U.S. undercut China’s current long game. The country is quietly buying influence in the region to an extent that would likely surprise most Americans, even those who are aware of the Belt & Road initiative and the rise of high-quality global Chinese brands. When Latinos think about EVs, they’re thinking about BYD, not Tesla. I’ve taken multiple Ubers in JAC vehicles and admired the Zeekr EVs on display in their flagship Bogotá showroom. Huawei and Xiaomi are the default phones for the lower and middle-income classes.

China is also building infrastructure. In November 2024, President Xi visited Peru to inaugurate the massive Chinese-owned Chancay Megaport on the Pacific, and subsequently hosted the presidents of Brazil, Colombia, and Chile in Beijing. There, they announced further Belt & Road infrastructure, including a massive Chinese-funded 3,000 km cross-continental freight railway from Brazil’s Ilhéus Port on the Atlantic to the Chancay. This railway will partially help circumvent the need for the Panama canal.

The country that finances Venezuela’s rebuild will be the one that captures the spillovers from its rebound.

I don’t say all of this as a geopolitical analyst. I’m a gringo business owner and operator who has worked with Venezuelans and been blown away by the talent, optimism, and potential of the region. So much so that I am actively evaluating the opportunity for Somos to expand into Venezuela.

I once hired a dishwasher named Cesar in my restaurant in Colombia. Cesar is a former small business owner from Venezuela who walked 72 hours to Bogotá across the border holding his newborn baby, despite having been robbed. He made it to Colombia. Within 5 years, Cesar saved up enough to open his own taco joint and now has three restaurants of his own.

Cesar is one of the estimated 8M people who have left Venezuela in the past ten years. This is a quarter of the population, a New York City’s worth of the country’s best and brightest talent, working-age men and women looking to build a life elsewhere.

The experiences Venezuelans have survived through over the past quarter century of Chavismo1, combined with the institutional memory of a country that was once richer per capita than Spain, Greece, or Israel, has created an entrepreneurially minded group of people with the grit and perseverance to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles and thrive outside of their home country.

Imagine if we unleashed this talent to rebuild Venezuela from the ground up. Imagine the promise of a Nova Gran Colombia, with Venezuela a force instead of a blocker.

Gran Colombia

A little history for those unfamiliar with the concept of Gran Colombia. Back in May 1819, Simon Bolivár campaigned to liberate New Granada, which we now call Colombia, from the Spanish. He led a combined army of Venezuelan and New Granadan troops from Venezuela’s flooded plains, into the Casanare Province, and up to the foot of the Andes Mountains, and over into New Grenada. The Spanish, who had assumed the Andes were impassable during the rainy season, were caught completely off guard. Within weeks, Bolívar’s ragged survivors had regrouped, recruited local support, and routed the royalist forces at the Battle of Boyacá on August 7th, a decisive two-hour engagement that effectively ended Spanish rule.

With New Granada secured, Bolívar moved quickly to formalize his vision of unity. In December 1819, the Congress of Angostura proclaimed the creation of Gran Colombia, merging Venezuela and New Granada into a single republic, with Ecuador to be incorporated once liberated.

Bolívar’s logic for a unified South American Republic was straightforward: if they were fragmented, the former Spanish colonies would be weak, poor, and perpetually vulnerable to reconquest or foreign meddling. United, they could pool military resources to finish the wars of independence, command respect on the world stage, negotiate trade agreements from a position of strength, and develop shared infrastructure across a territory blessed with Caribbean ports, Andean agriculture, Pacific access, and vast natural resources. A large, stable republic might even attract the European investment and migration that the young United States was already drawing.

The experiment barely outlasted its architect. Regional elites resented distant rule from Bogotá; Venezuelan leaders like José Antonio Páez chafed under centralized authority and began agitating for autonomy almost immediately. The geography that Bolívar had so dramatically conquered worked against him in peacetime. The Andes and jungle landscape made communication slow and governance nearly impossible across such distances. By 1826, Páez was in open revolt. Venezuela formally seceded in 1830, Ecuador followed months later, and Bolívar, sick and disillusioned, died that December.

Not once in the intervening two centuries have the countries that previously made up Gran Colombia been both governed by a fairly elected government and operated fully at peace.

Today, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama all have democratically elected governments. Colombia has been at peace with the Marxist guerrilla group FARC since 2016, though smaller conflicts continue. Panama has been stable since 1989. Ecuador, the smallest, faces a severe organized crime crisis but the state is not in armed conflict. Things in the region are not perfect, but they’re as good as they’ve been in a long time. Venezuela has been the most notable exception.

As of January 3rd, that may be changing.

The Potential of a Nova Gran Colombia

Bolívar failed partly because geography made a single republic ungovernable. In 2026, the question isn’t whether the Andes are passable in the rainy season, but whether modern infrastructure, money movement, and rules can make the region economically contiguous. If they can, you get the benefits of unity without the need for a single flag.

A free Venezuela offers the chance for a new bloc with a population approaching Mexico’s and a GDP that would rank between Taiwan and Belgium’s to develop side-by-side. Had Venezuela’s post-2012 collapse never happened, Nova Gran Colombia’s GDP would fall between Saudi Arabia and Poland’s2.

This bloc would count among its resources the Panama Canal as well as large coasts on both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans for transport, along with massive oil, gold, mineral, and freshwater reserves3.

It has a young4, educated5, and urban6 population. All of this is with the region’s highest-potential country, Venezuela, hamstrung by socialism.

With a liberated Venezuela, this bloc could grow to become as strategically important to the U.S. as Mexico and Canada or the EU.

A free and democratic Venezuela could drive reverse migration for the 8 million strong diaspora and become a destination for migrants of all nationalities and socioeconomic levels. Cheap real estate, amazing climate, and a national industry (oil and gas) made for well-paid, technical jobs should make Venezuela a destination for everyone from digital nomads to blue collar workers from Mexico to Chile, and even U.S. retirees looking for alternatives to Florida, Arizona, and Costa Rica. Venezuela is missing 8 million people versus where its population would have been prior to Chavismo. It can add back many more. This reverse migration would help Venezuela, Latin America, and the United States, which has been a destination for many who have fled.

A stable Gran Colombia would make an ideal AI hub for the Western hemisphere. We are in the middle of an AI capex supercycle, and the bottleneck is no longer chips, but power, permits, and fiber. The IEA estimates that data centers used roughly 415 TWh of electricity in 2024, and projects that figure could roughly double to about 945 TWh by 2030. Gran Colombia sits in a rare spot that makes it an ideal part of the solution. It is geographically central to the Americas, and it is wired into the global internet through brand new, high capacity submarine cables such as TAM-1, CSN-1, and MANTA. These cables land in Barranquilla or Cartagena, Colombia, with low latency to principal datacenter hubs including NAP of the Americas in Miami. Miami to Bogotá pings average around 45 milliseconds. And there are multiple regions at altitude for year-round cool temperatures.

But geography is table stakes. Power is the real story. Unlike most emerging market “AI hub” pitches that depend on intermittently clean electricity, this region already runs on dispatchable hydropower at scale. Hydropower was 58% of Colombia’s electricity generation in 2024, supported by roughly 11 GW of installed hydro capacity. Venezuela generated about 64% of its electricity from hydropower in 2021 and has roughly 16 to 17 GW installed. The crazy thing is that the current hydro story is only a fraction of the potential. Colombia’s theoretical hydro potential is about 56 GW, and Venezuela’s technically feasible potential is about 62.4 GW. Those numbers imply a massive opportunity for firm, low-carbon baseload that could anchor hyperscale data center buildouts, especially when complemented by gas for reliability. APD, Somos’s sister company, is working on turning this potential into reality.

A Marshall Plan in the region could involve the U.S. government underwriting credit to build out the world’s biggest datacenter hubs in Colombia and Venezuela. In the same way that Apple invested $50B per year in capex in China in the 2010s to build out manufacturing capacity, today’s data center and power capex wave need not be confined to the borders of the United States.

A clean slate approach in Venezuela offers the chance to think about infrastructure for the 21st Century. Data centers are just one piece of the puzzle. Venezuela has the opportunity to build ports with fully automated docking and customs, interlocking energy microgrids to accommodate distributed solar and storage, roads and fulfillment distribution facilities rebuilt to prepare for the arrival of self-driving cars, and even microairports for flying cars and Zipline-esque drone logistics hubs. This last one is an opportunity in Venezuela, as well as in Colombia, where mountains separate our largest cities.

It is hard to overstate how important modern infrastructure will be to this transition.

To be sure, even a return to pre-Chavismo conditions would be a boon to the region. Bilateral trade between Colombia and Venezuela peaked at $6-7 billion annually in 2006-2007 before collapsing to just $200 million by the early 2020s. Since the 2022 border reopening, trade has grown, which shows that the link is still there and latent. Still, the countries are trading dramatically below their peak.

That said, the fact is that Latin America trades very little with itself, and trade is required for the economic impact to take hold. A 2004 IMF paper found that a 1 percentage point increase in trading partners’ growth is correlated with up to about 0.8 percentage points higher domestic growth. But per JP Morgan, just 15% of Latin America’s exports stay within Latin America, compared to ~40% in Asia-Pacific and 65% in Europe. This is a reflection of commodity-export concentration, poor cross-border infrastructure, and decades of political fragmentation.

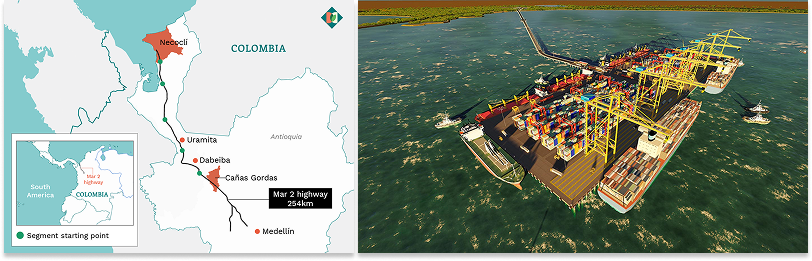

This is an old problem, one that predates Bolívar, potentially fixable at last with modern infrastructure. One of the reasons Gran Colombia fell apart so quickly was that it was a geographically challenging region to govern; autonomous flight can fly over the natural impediments and provide a bigger economic boost in our region than any in the world. More imminently, projects like the Autopista el Mar highway, which connects our home state of Antioquia to the new Puerto Antioquia, will take the over-ground trip to the coast from fourteen hours down to four. The highway will tunnel through the mountains, and could be built across borders if project developers and their backers had confidence in the region.

Modern infrastructure is both an opportunity and a necessity. Venezuela will need to rebuild, and in the process, we may have the opportunity to defeat the natural foe that frustrated Bolívar two centuries ago.

Finally, a dollarized Venezuela could demonstrate what “leapfrogging” looks like for economies now that the GENIUS Act has created a U.S. regulatory framework for stablecoins. Venezuela has been living through de facto dollarization since Maduro relaxed controls in 2019, with dollars widely used for pricing and transactions. And as dollars have remained scarce and difficult to move through the formal system, the country has also become de facto stablecoin-ized. A Chainalysis report found that from July 2023 to July 2024, 47% of transactions under $10,000 in Venezuela were conducted using stablecoins. That combination makes Venezuela an unusually good test market for the U.S. exporting regulated digital-dollar infrastructure, especially once GENIUS creates clearer rules for issuers. A dollarized, bank-light economy like Venezuela is exactly where “stablecoin settlement + merchant acceptance” could leapfrog legacy rails. It would create more demand for U.S. Treasuries, as well.

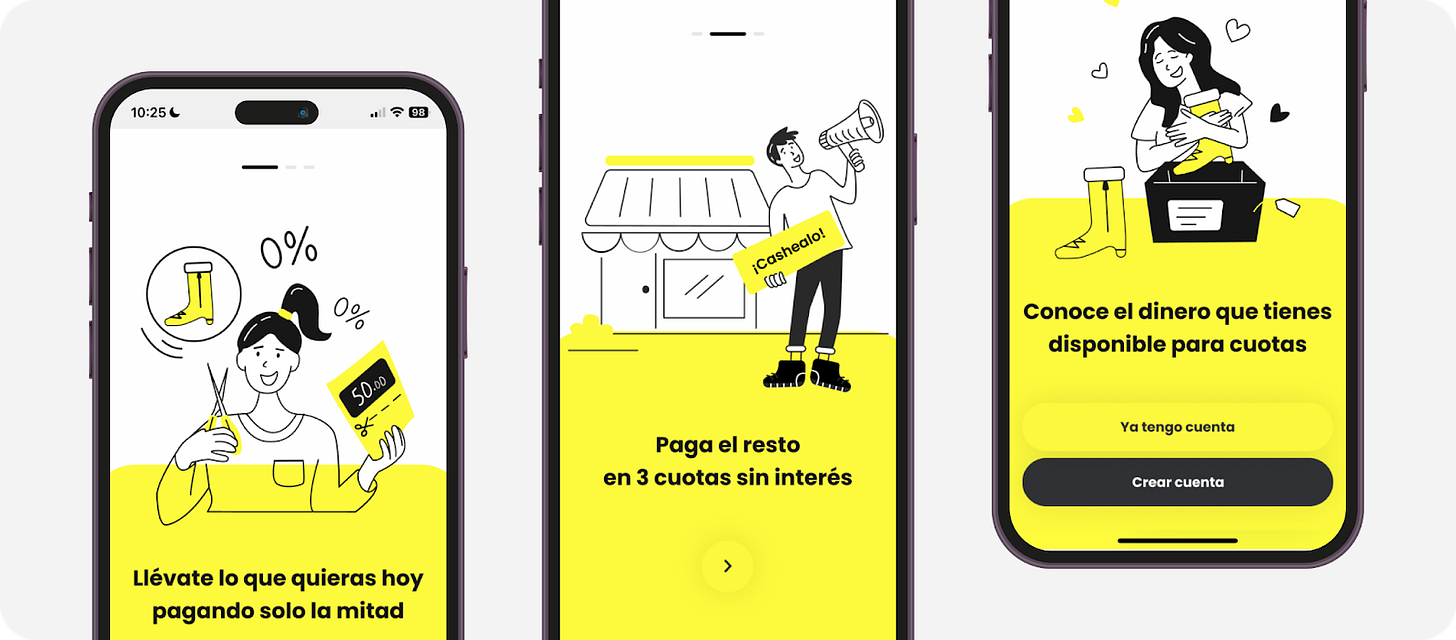

No company better demonstrates the country’s capacity for financial innovation out of necessity than Cashea.

A $0-200M run-rate revenue jump in three years may not raise eyebrows the way it would have prior to the AI era. But $0-200M run-rate revenue for a LatAm startup that only raised $2.5M and has been profitable for two years is unheard of.

Cashea, founded in 2022, is a dollar-denominated interest-free BNPL for SMBs “built in Argentina but made for Venezuela.” It processed over 4% of Venezuela’s GDP in GMV as of September 2025, with a goal to process more than 6% by year end.

But Cashea was unable to raise real VC capital or obtain a substantial credit line to operate in Venezuela. The country was seen as too unstable. So Cashea partnered directly with merchants who fund and bear the loan themselves. These merchants then offer credit to their customers, which Cashea guarantees if they default. It’s a hack that is as difficult to bootstrap in Venezuela as it would be in the U.S. or anywhere else, but a lack of credit availability in the system now drives a model which has been adopted by 5,000+ merchants across the country. It is growing exponentially, without major financing costs for Cashea, and has a delinquency rate below Affirm or Block’s Afterpay. Cashea charges merchants a fixed commission and has now begun to facilitate merchant’s receivables in a version of factoring offered on the Venezuelan Stock Exchange.

The company doesn’t need a massive balance sheet or financing facility, and it has completely obsoleted the need for traditional credit card rails, which are non-existent in the country anyway.

Here’s a great overview of the company from Fintech Leaders:

Cashea proves that necessity breeds innovation. A “clean slate” Venezuela will need a lot of it.

But clean slates can also be green pastures. They can help new market entrants build from scratch, innovate on business models, and leapfrog state-owned incumbents.

That is the opportunity we are excited by at Somos Internet, the fastest-growing ISP in Colombia. We build vertically integrated digital infrastructure to give customers better internet at a structurally lower cost. Our users love us. And we’re making plans for international expansion.

Until January 3rd, Somos hadn’t seriously entertained the idea of entering Venezuela. It was attractive, but there was too much risk.

Now, we are considering the opportunity. Venezuela’s capital city, Caracas, checks most of the boxes we look for when considering new markets.

Large market size and high population density: Caracas is a major city with a population the size of Chicago (three million) and a population density greater than San Francisco, which makes it a perfect market for a new entrant like us. We can find more potential customers for every km of fiber deployed.

High existing ARPUs and low market penetration: A lack of private competition has left Venezuelans with a raw deal. State-owned CANTV offers fiber to the home (FTTH) services starting from $25/month for 60 Mbps. This is extremely expensive in 2026. And the website claims to offer 1 Gbps at $150/month. Thanks in part to these expensive plans, the penetration of fixed internet is low and many households rely on cell data as their primary form of connectivity. We believe that giving people access to great internet increases economic opportunity. It is a virtuous cycle.

Early adopter culture: The general Venezuelan population is open to trying new alternatives (see Cashea’s adoption) because they are dissatisfied and lack legacy offerings.

Proximity to existing infrastructure: This isn’t a dealbreaker for Somos, but it is, on the margin, better to expand to adjacent geographies rather than jump to new geographies entirely. This would require new contracts with Tier I providers to maintain a unified network architecture.

Despite its attractive characteristics, we are not jumping into Venezuela yet. The situation is still too uncertain.

But given that we are actively evaluating the opportunity, our perspective may provide useful color on what businesses are looking for before committing to rebuild the region.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Not Boring by Packy McCormick to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.