Story Time

The Progressive Decentralization of Narrative

Welcome to the 1,637 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! Join 69,350 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… WorkOS

Startups are getting bigger, faster. Not just by valuation, but by actual revenue. The main reason? Better off-the-shelf infrastructure. Modern companies can write a few lines of code to do things that used to take years and millions of dollars in the past.

Like, for example, sell into enterprises. WorkOS helps you start selling to enterprise customers with just a few lines of code. WorkOS supports three features that enterprises require of any vendor: Single Sign-On (SAML), Directory Sync (SCIM), and Audit Trail (SIEM). You don’t want to waste your valuable engineers’ time building those yourself.

Development teams at fast-growing B2B SaaS companies like Hopin ($5.65B), Webflow ($2.1B), and Vercel (>$1B) use WorkOS to get enterprise-ready in just a few hours. Just like they use Stripe for payments or Twilio for communications.

WorkOS unlocks pools of sweet, sweet enterprise money, faster. Get started today with Google auth and magic links included for free:

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday!

I spend 90% of my time thinking about stories and narratives, and like so many other things, narrative formation is getting decentralized. This is my attempt to figure out what’s happening and where it’s heading.

Let’s get to it.

Story Time

Crafting and telling stories is part of what makes humans humans. Stories let us coordinate across time and space. Stories are undeniably important.

But as things get more and more abstract, as we move evermore towards a world of abundance, and as more and more of what we do and buy is for things beyond survival -- like social capital, entertainment, and utility -- the ability to weave a good narrative out of a tapestry of little stories is more valuable than it ever has been. How best to do that has changed and gotten a whole lot more complex.

Imagine, as a quick and extreme thought exercise, that you lived in a tribe of hunter-gatherers 12,000 years ago. There were about 100 people in your tribe. Many were family members. Food was always the #1 priority. If you needed to convince the men of the tribe to hunt, what kind of story would you need to tell and how would you get the message out?

Something pretty simple like, “We need to go hunt now or we will not have meat and we will die,” spoken directly to your fellow tribespeople, probably worked like a charm.

Everyone heard the message -- there were no distractions or competing messages -- and everyone understood the immediate importance. So you went out and hunted.

Things are obviously not that simple anymore. For one, most people never have to be bored unless they consciously choose to be. There are a million demands on our attention. Plus, we don’t need to hunt for food. We open DoorDash or UberEats or Instacart or GoPuff or Farmstead and food magically arrives at our doorstep in no time.

Imagine coordinating 100 people to decide what to eat for dinner tonight. Puja and I have a hard enough time deciding among all the options ourselves. Life is easier, but deciding is more complex.

I was reminded of how hard it is to spread a message in a conversation I had at a wedding last weekend. A few friends were talking about why the Olympics’ ratings were so bad. Sure, it was weird not having fans, and sure, America’s best athlete competed less than expected, but the real challenge was, we didn’t know any of the other athletes’ stories. In the past, there would have been months of build-up, with profiles on America’s athletes all over ESPN and The Today Show and in the local newspaper. We all would have been watching the same shows, and those shows would have told stories that convinced us to care. They would have crafted a narrative.

One smart friend who works in media asked: “How would you get those stories out to everyone today?” Hint: you can’t. And that’s the Olympics! It’s bringing one of the world’s most beloved brands to the table.

On the other hand, in my small corner of the internet, NFTs have completely dominated the conversation. Not everyone in the world is talking about NFTs. Even in the midst of NFT-mania, only 109k people have bought an NFT on OpenSea this month, according to rchen8 on Dune Analytics.

NFTs have owned the conversation in a small-but-growing niche, and they’ve done it not by telling one, consistent story -- there is no NFT, Inc. -- but by giving people the tools, ownership, and incentives to go tell the million little stories about NFTs that build up to one loud narrative.

In a post last week, The Opening, Union Square Ventures’ Fred Wilson wrote:

I am not saying NFTs are the next big thing. I am saying that consumer experiences built on a crypto stack are the next big thing. I am saying that NFT experiences are showing the way.

The same applies with modern storytelling and narrative-building. I am not saying that NFTs are the next big thing (although I’m bullish). I am saying that the way NFT owners and supporters tell stories is showing the way.

In a world of abundance, attentionis the scarcest resource, and peoples’ attention is hard to earn. It requires new tactics.

I’m seeing the same shift play out in the areas we talk about so much in Not Boring -- tech, venture capital, markets, and crypto -- from top-down storytelling to bottoms-up narrative building. Owning the narrative can be self-fulfilling, helping companies:

Acquire customers more cheaply

Hire stronger employees

Create better partnerships

Attract follow-on investors at a lower cost of capital

Similar dynamics apply to VC firms, crypto projects, and even stocks. Stories turn into narratives, and narratives have real, measurable impacts.

That shift is the foundation of both Not Boring the newsletter and Not Boring Capital. I’m obviously biased regarding the importance of storytelling, but I’ve spent every day for the past 15 months doing it and watching how others do it. Studying narratives has been my fascination.

So how do you build a modern narrative?

Today, we’ll cover:

From Storytelling to Narrative Building

Narrative in Venture Capital and Startups

Lessons from Crypto

From Storytelling to Narrative Building

Every day, thousands (millions?) of companies and VC firms launch in-house essays into the abyss. They want to “own the conversation” around X, and so they write about X, and … crickets.

They were told content is important, and they made content! Why didn’t it work?

Corporate essays are kind of like sales, and according to Alex Danco, we’re past sales and on to something better: world building.

(Note: this is separate from the Not Boring concept of Worldbuilders, although successful Worldbuilders certainly use story to great effect.)

In World Building, Danco argued that yes, everything is sales, but sales isn’t enough. You need to build worlds. In a world of “abundant narrative and complex choices… You need to build a world so rich and captivating that others will want to spend time in it, even if you’re not there.”

That means telling multiple, related stories, and telling them over and over again. It means making your overarching story clear enough that others can repeat it themselves.

In a follow-up conversation with Jim O’Shaughnessy on Infinite Loops, Danco provided more color on why world building is important today. There are two reasons, both of which come down to abundance.

One reason is practical. There are too many people to sell to directly.

The other is strategic. What’s constrained in a world of abundance, when you can read, watch, or listen to anything for practically $0? Attention.

Or, as Danco put it, “What is starting to become scarce is people’s actual interest in you.”

Stories form the foundations of worlds in which people can spend time without you. In an age of abundant things, and even abundant stories, the ability to tell a great story is a crucial building block. But stories alone aren’t enough. You need to let your community join in painting a narrative.

Stories and narratives sound like they’re the same thing. So much so that Writer suggested I drop the “and narratives” because it’s redundant.

The dictionary agrees with Writer. Story and narratives are synonyms, according to Merriam-Webster. For our purposes, we’ll distinguish between the two:

Stories are discrete. One essay, one event, one customer experience. Someone might say, “Did you hear the story about Company X doing thing Y?”

Narratives are made up of all of the stories about a company, which crystallize into what people believe and say about the company as a whole. The narrative around a company is similar to its reputation or brand.

If a company writes a blog post about its origins, that’s a story. If an investor goes on a podcast to talk about the company, that’s a story. If the founder writes a thread on Twitter, that’s a story. If a customer tells their friends about a good interaction they had with customer service, that’s a story. If a developer tells other developers the company’s APIs are clean, that’s a story. If TechCrunch reports on their latest funding round, that’s a story.

These individual stories add up to form a narrative, which constantly changes and evolves, but has a direction, size, and tone.

But a narrative also compounds. Positive stories add up, particularly when they’re positive for the same reason. Stories reinforce stories reinforce stories. A narrative forms. There’s no formula, but the ingredients are:

Number of stories told

Ratio of positive to negative stories

Consistency of positive or negative attributes

Number of different storytellers

Credibility of storyteller to the target audience

Confirmatory updates

Persistence of stories over time

The best thing for a company or project’s narrative is to have a lot of people with credibility to the target audience tell stories with roughly similar positive themes again and again over a long period of time, with new examples of the same positive themes added in. The more authentic and the less coordinated it all seems, the better.

It’s hard to pull off, particularly because so much of it needs to be organic, seeded with just the right amount of direction from the company or team and its core supporters. When it works, though, it’s a powerful thing, the benefits of which compound over time.

Benefits compound because narratives are Lindy. The longer people believe something about a company, the longer they’re likely to believe something about that company.

A great current example is Apple vs. Facebook.

The narrative around Apple is that it’s a world-class design-and-privacy-first company whose products say something good about the people who own them. That narrative began, very intentionally, under Steve Jobs, and it carries through to today. It’s armor. Anything that doesn’t fit the narrative practically bounces right off; anything that feeds the narrative gets added.

Claims that the App Store’s 30% take is anti-competitive have barely grazed the company. Apple’s recent decision to put backdoors in iCloud and iMessage has caught the ire of the privacy-passionate, but hasn’t dented the company’s sterling reputation.

Facebook’s narrative was formed in articles about its brash and awkward founder, Mark Zuckerberg, in the film The Social Network, in the company’s old “Move Fast and Break Things” motto, in Zuck’s sweaty and stuttering speaking appearances, and in the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Facebook’s positive impact on small businesses, and free WhatsApp messaging service that connects over a billion of the world’s poorest internet users, are rarely discussed.

If you looked at both companies’ activities over the past couple of years with fresh eyes, you might think that Facebook is the good company and Apple is the evil company, but we don’t look at anything fresh. We look at everything through a preexisting narrative. Those take time to shift.

Zuck hydrofoiling is a step in the right direction, but once a narrative is set, it takes time to shift. The respective narratives may be one reason that Apple, largely a hardware company, trades at a 29x PE, while Facebook, a software company, trades at 26x.

These are extreme examples involving two of the world’s most valuable companies, but smaller examples of the same phenomenon play out all of the time. Stripe is a fantastic modern example of a company around which such a strong narrative has been built that it achieves the holy duo: 1) people love talking about Stripe, and 2) they give it the benefit of the doubt when they do.

Apple, Facebook, and even Stripe all built their narratives during a time when the competition for attention was less fierce. The tricks that got them here probably won’t work for you.

The old way to build a positive narrative was to tell a consistent story about yourself over time. The new way is to have other people tell your story for you, either directly or by association.

Narrative in Venture Capital and Startups

The idea that companies and funds need to tell their story isn’t new. That’s what marketing and PR departments have always been for.

In 2009, Tom Foremski wrote an article in ZDNet titled Every Company is Becoming a Media Company… about Cisco. That same year, Andreessen Horowitz launched the first venture fund that harnessed the power of storytelling. (Listen to the fresh Acquired two-parter on a16z here and here.)

When a16z launched and Foremski wrote that article, the big idea was that companies and investors should be able to tell their own stories, directly.

What’s new is that today, power lies in sharing the mic.

In June, a16z launched its own media brand, Future, to double-down on an owned media strategy that’s clearly been working. Some of the essays on Future are written by a16z partners, but many are written by entrepreneurs in or around the a16z ecosystem. When the site launched, there was a fair amount of journalist hand-wringing about a16z’s attempt to go around the media and get their message out directly, but that’s not what it’s about. I’d imagine their posts don’t get nearly as many views as a TechCrunch article. What it’s really about is building a place where like-minded entrepreneurs and investors can come to paint compelling stories about the future, together.

In a similar vein, solo capitalist Josh Buckley launchedHyper in July. Hyper is part-VC, part-accelerator, part-community, that, according to its website, is “always looking at companies through the lens of how we can help with our unique distribution and community features.”

Everything about Hyper is geared towards this new means of distribution. Buckley built Hyper in partnership with ProductHunt, which he owns and which is a key source of distribution, along with AngelList, Sequoia, Harry Stebbings’ 20:VC and, of course, a16z. The people involved have huge audiences. Naval has a ton of Twitter followers. Harry Stebbings has a podcast that’s hugely popular with the right audience. Sriram Krishnan runs a top Clubhouse show. Jeffrey Katzenberg ran Dreamworks, for Chrissakes.

Individually, any of these brands or people could tell a compelling story. Together, over time, they can shape a narrative.

This is the same reason that so many startups are welcoming more individual investors, particularly those who can help tell their story, onto the cap table. It creates more surface area for more people to tell the company’s story, which lets companies control their own narrative.

Recall that a narrative is shaped by, among other things, the number of stories told, the number and credibility of storytellers, the consistency of the positive aspects of the stories, and the persistence of the stories over time. Collaborative VC funds made up of a constellation of credible people have the right mix of credibility and incentives to build a company’s narrative over time.

That’s why a16z is building a collaborative media brand. It’s why Hyper is likely to be such a valuable investor to its portfolio companies. It’s what I’m trying to accomplish with Not Boring Capital and Sponsored Deep Dives: find the companies with compelling products and stories to tell, and help them accelerate turning those stories into a cohesive narrative that cuts through the noise.

It’s a delicate balance, though. A lot of founders are welcoming more investors with audiences onto their cap tables. It’s a smart move, but to get the most out of it, founders need to be thoughtful about how to use those investors. Everyone tweeting the same thing around a big announcement is better than nothing, and might help with early momentum, but it’s far more important to figure out how each person on the cap table can authentically lend credence to the company’s narrative over time.

Even better, those investors should be one of many stakeholder groups with the incentive and ability not just to parrot out the corporate narrative, but to add stories that contribute to an emergent and authentic one.

The best guide for how to do that well is crypto.

Lessons from Crypto

In a world of abundance, we’re spending more money and time further up Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

We don’t need most of the things that we buy or spend time on today. Even the best, most useful B2B SaaS is a nice-to-have, however important it seems. The beautiful thing about NFTs, and why they’re such an interesting case study, is that they’re the purest, most honest distillation of that trend. Of course we don’t need a $10k jpeg. Duh.

The thing that people scoff at -- these are just stupid jpegs! -- is the same thing that makes them so rife for narrative building. They’re largely empty vessels into which the community of owners and supporters can pour stories that turn into a narrative. Studying what makes certain NFTs valuable is instructive for anyone trying to build a narrative today.

Let’s start with CryptoPunks. CryptoPunks are seen as being valuable because they’re OG NFTs, but there are other old NFT projects that haven’t caught fire like Punks have. My guess is that what makes Punks valuable is that the stories around them have accumulated and compounded into a positive narrative.

When a Punk sells for over $7 million, that’s a positive story.

When Jay Z buys a Punk, ditto.

When Punk Comics turns certain Punks into characters in a story, that’s both a literal story and a story about the potential for this IP to generate value.

The fact that CryptoPunks are old isn’t the reason they’re valuable; it’s just one story that feeds an overarching narrative that says: “These are the most legit NFTs.”

It’s also useful to look at a newer project to see how these narratives start to form.

On Saturday night, I waited two hours in a chaotic Discord, trying to mint an Ape from Degenerate Ape Academy, an early Solana-based NFT project. The core team delayed the launch due to technical issues. When they finally went live, they minted 10,000 Degen Apes, and sold out in eight minutes.

The page stayed broken for me the whole time, so I didn’t get one, but those who did are already figuring out how to tell their Apes’ story, organically.

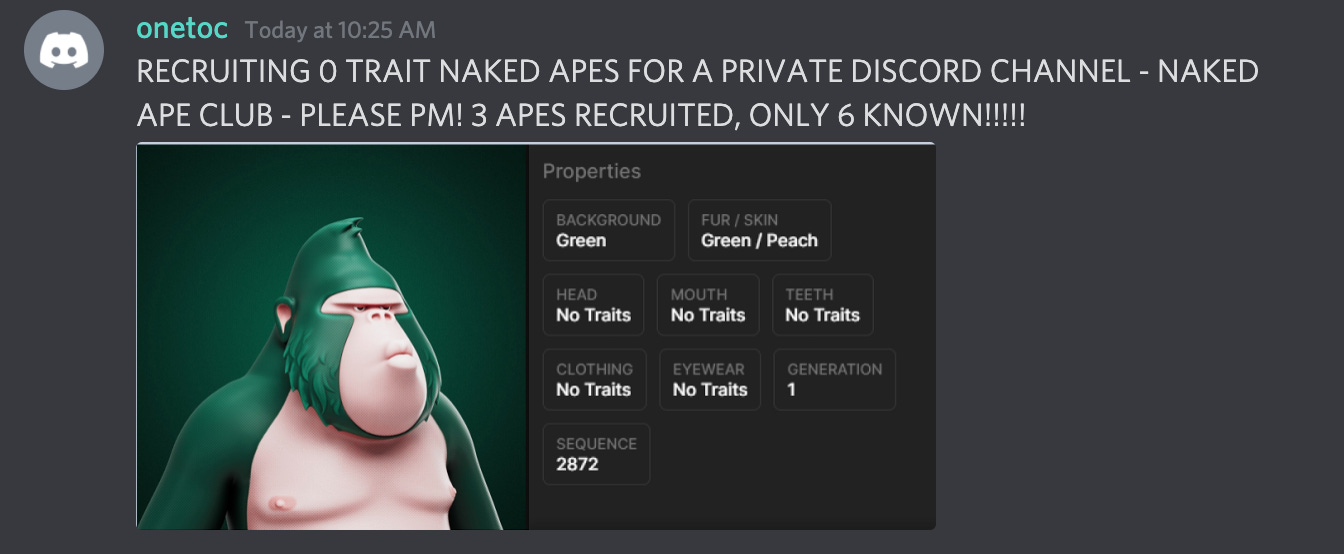

This is one of many similar messages in the Discord highlighting micro-communities of certain types of Apes banding together to make Apes that look like theirs more valuable, which, in turn, will make Degen Apes on the whole more valuable. It’s even making Solana itself more valuable -- SOL’s price has risen from $45 on Saturday night to $62 this morning!

This is what Danco meant by building worlds so rich and captivating that people will want to spend time in them. The Degen Apes core team built a world that others could begin to make their own -- largely because they have both a financial and a social motivation to do so -- and from here, most of the million little stories that add up to a narrative will be written by the community. It’s stories all the way up.

I think this is why certain NFT projects, even new ones, do well while others flop. Pudgy Penguins, Art Blocks, and Bored Ape Yacht Club have all captured the attention and imagination of communities of people, who in turn tell the projects’ stories, which forms a narrative around the projects that give them staying power. They built worlds in which other people want to spend time, and gave them clear building blocks of stories clear enough to repeat themselves.

Telling a shared narrative makes it more fun and immersive for everyone involved -- NFTs are a combination of investment, social network, community, and entertainment -- and makes the NFTs more valuable. That’s why I think fractional NFTs, instead of hurting value by lowering scarcity, have the potential to make certain NFTs even more valuable. If a key ingredient for a narrative is the number of stories told by credible people, then bringing more people together to own an asset and tell stories about it should accelerate the creation of a narrative.

I want to experiment with that thesis. I found a PartyBid for Punk #8721, Hooka Punk, put 1 ETH in, and invited people to join the Party.

We’re up to 21.3699 ETH. We need 60.9 ETH total. With this group, we should be able to buy it, and from there, we can decide how to tell Hooka Punk’s story and form a narrative around it.

All of this is happening bottoms-up in a little narrative petri dish. As Fred Wilson pointed out, what’s happening in NFTs is showing the way. Some key takeaways that extend beyond crypto and into anyone trying to form a narrative around their company, product, or project include:

Make it clear what you’re about so that others can use that in their own storytelling

Get people genuinely involved in what you’re doing and incentivize them to tell their own stories about it

Work with credible partners to tell your story in new ways to the right people

Embrace authenticity instead of trying to be overly polished (unless you’re Apple)

Give stakeholders places, like Discord servers, to coordinate

Amplify their stories when they feed into the main narrative

Stay open to the million ways that the narrative could evolve

It’s essentially the progressive decentralization of narrative. Create the building blocks, tell the initial story, and then get out of the way. It might feel uncomfortable, and it’s not the right approach for everyone, but in the competition for attention, you’re up against people who are willing to give up control to let the narrative take on a life of its own.

What we’re seeing now, of course, is just the beginning. As DAOs and Liquid Super Teams represent an increasing share of the investing and company-building landscape, a large source of their power will come from letting more people tell stories that shape the narrative around projects and companies. In a decade, it will seem outlandish to try to tightly control the narrative.

If every company was a media company a decade ago, and companies and funds invite more voices in to co-create their narratives today, the next decade will be all about organic, community-driven narrative creation and distribution.

Or, as Lin Manuel Miranda might ask, “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?

💼 Not Boring Jobs 💼

Foster: Senior Product Designer (NYC, Remote)

Launch House: Community Lead, Founder Community (Remote)

CommandBar: Software Engineer (San Francisco)

To find yourself a Not Boring Job, check them all out here. If you want to feature your job to 69,350 smart, curious people, reply to this email and let me know!

Thanks to Dan and Puja for editing!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading!

Packy

Packy, I have been thinking about this for a month, really. Thank you for putting it all in words. You see the game in a different level. Tks sir!

Very keen thinking and communicating, just what I and a lot of people needed to hear. Next time I see you down at the bar, drinks on me. Thanks Packy)))