Welcome to the 1,138 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Tuesday! If you haven’t subscribed, join 189,368 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday! After a hectic start to the year, we’re back in the Monday slot hitting your inbox with 12k words to kick off the workweek and it feels good.

Back in September, I asked Twitter for their most magical tech experiences of the past year. In second place, sandwiched between generative art and crypto wallets, two topics I’ve written a bunch about, was the product I use more than any other: Arc by The Browser Company (you can skip the waitlist with that link, btw).

After I saw the poll results, and wrote a little bit about Arc in Indistinguishable from Magic, I knew I wanted to write a full piece about the company. Originally, the main question I had in mind was: why would such a talented team with the ability to craft such a delightful product waste their prime years building a browser? Chrome has the market on lock. I viewed their efforts as an amazing contribution to consumer surplus.

But when The Browser Company’s CEO Josh Miller reached out to thank me for the kind words about Arc and offering to explain the company’s big vision, I took him up on it, and about three minutes into our call (a good, old fashioned phone call), I knew this piece was going to be much bigger than Arc.

Since the launch of the first modern browser, Mosaic, thirty years ago, the browser has been the turf on which some of tech’s biggest battles have been fought. Given its place in the tech stack as the window between the user and the World Wide Web, it’s a powerful demand traffic controller and a unique beneficiary of all of the innovation that goes on beneath its surface. And even when the Wars seem won, when Chrome seems locked in as Internet Explorer did before it and Netscape Navigator did before that, something shifts in the internet landscape and opens the door for new competitors with a fresh approach.

I think we might be in one of those moments right now. With AI as a catalyst, the giants are signaling their intent to do battle in the browser once more. But I, of course, am rooting for the underdog with the freshest product: The Browser Company. Theirs is the Internet Computer I hope everyone is using when the dust settles.

This is not a Sponsored Deep Dive, the Browser Company isn’t paying me, and I’m (sadly) not an investor; I just genuinely love the product and think that the Third Browser War is one of the most interesting stories in tech that not enough people are talking about. It reveals the giants’ strategies - their strengths and weaknesses, packages up the history of the internet, and hints at the way billions of people will spend hours every day in the near future.

Let’s get to it.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Masterworks

As we’ll cover today, everything is moving to the cloud. That’s true of obvious things like apps and data, but it’s true of less obvious, more beautiful things, too… like art.

I don’t own much great physical art, other than a set of vibrant Takashi Murakami prints that a friend gave to me. I can’t afford the good stuff. But on the internet, I own paintings by Basquiat, Haring, Warhol, and even Picasso. Well, I own shares in those paintings at least, thanks to Masterworks.

I’ve been working with Masterworks for years, and personally investing with them the entire time. In the beginning, before they’d sold any of the pieces they’d purchased, I just thought it was a really cool way to access an inaccessible and less correlated asset class while beautifying my portfolio. Over the past year, though, they’ve begun selling works in the portfolio for a gain. In fact, every single one of Masterworks’ 11 exits to date has returned a profit to their investors, totaling more than $30 million in payouts.

A majority of those sales weren’t in the go-go era of “everything goes up”, meme stocks, and bitcoin at 60k… but while inflation soared to decade highs, and financial markets plummeted. They’re proving out their thesis: that art can perform well even when other assets don’t.

New offerings are launching every week, and tend to sell out fast. But as a longtime partner I’ve secured some VIP passes to skip their waitlist at the Not Boring link:

See important Regulation A disclosures here.

Internet Computers

There may be no application better positioned to benefit from the rush of rapid innovation we’re swimming in than the humble browser.

I say humble, because admit it: you take your browser for granted. The browser has become so synonymous with the internet, and the internet has become so enmeshed with our lives, that it’s become like the water in that David Foster Wallace speech:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?”

And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

What the hell is browser? Like a surfer who paddles with the strength of the gods, the browser has both created and ridden the biggest technological wave in history.

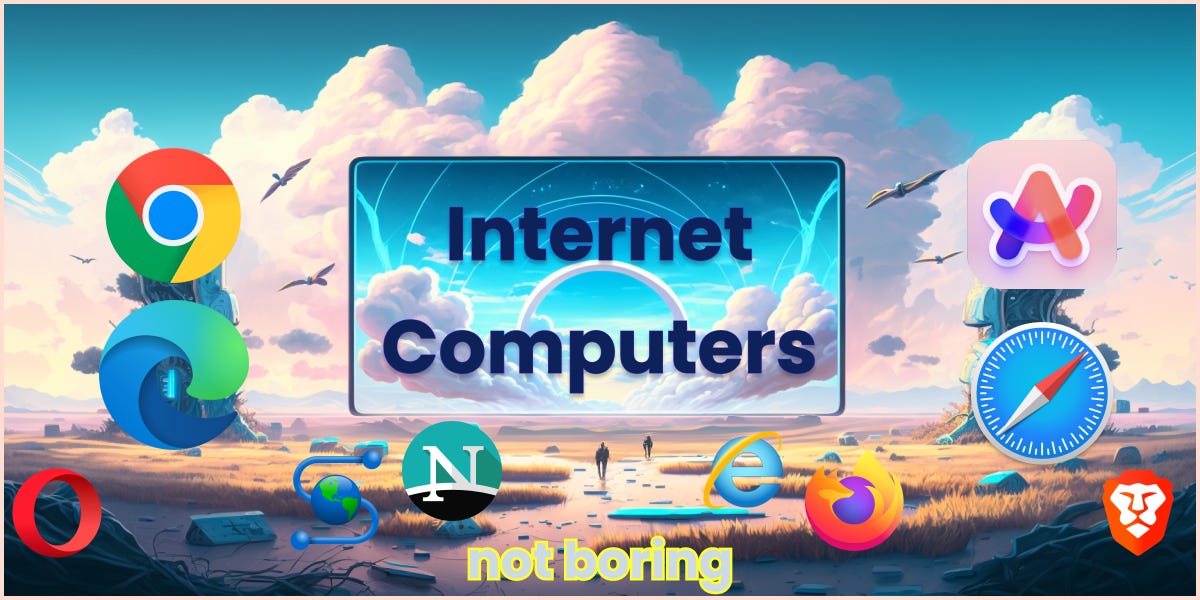

A stunning 5.3 billion people use browsers to access the wonders of the World Wide Web, an enormous number that has grown 24% since 2019. One-third of the Earth’s population, 2.7 billion people, are yet to come online. When they do, rest assured, they’ll access it through a browser, whether on their phone, their desktop, or some futuristic hardware.

This is a piece about which browser they might use, and how.

Browser usage is a relatively recent phenomenon, a decade more recent than Excel. When Marc Andreessen launched Mosaic in January 1993, less than 1% of the tiny number of netizens used a browser. Six months in, 100,000 people connected to the internet through Mosaic. By December of that year, Mosaic counted 1 million nerds as its earliest users. By the time Andreessen’s next browser company, Netscape, IPO’d in 1995, there were 16 million people online. Nine years later, Facebook debuted to an internet audience of 745 million. The next year, in 2005, the internet crossed the 1 billion mark. Now, 5.3 billion of us live online.

Over that same period, the time we spend in browsers has increased with the browser’s capabilities. I just braved my Screen Time Report and discovered that each week, I spend roughly one day’s worth of hours in my browser. I have an especially online job, and it’s hard to find broad browser usage data to back up my personal anecdata, but one way to ballpark it is by thinking about all the things that browsers can do today that they couldn’t before.

If one of the most remarkable things about Excel is that it’s thrived despite the unbundling of its peripheral functionality into hundreds of specialized apps…

… then perhaps the most incredible thing about the browser is how much of our digital activity it’s been able to inhale.

In fact, as Excel and other desktop applications have gotten unbundled and turned into cloud-based SaaS products, the browser has been a major beneficiary. The biggest tech acquisition of the past year – Adobe’s now-contested $20 billion acquisition of Figma – is a win for the browser. All of the “Figma for X” companies that followed in its wake are a win for the browser. Products like Replit that bring the IDE online are a win for the browser.

Any time an application moves from your dock to a tab, that’s a win for the browser.

The browser is this incredible application that seems to only get stronger with each new tech cycle. When the vast majority of users interact with web3, they do it through the browser. AI has been an unmitigated boon for the browser, one that will only accelerate as intelligence moves up a layer, from walled apps to the browser itself.

As Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella put it at the Bing AI reveal event in February, “We’re going to have this notion of a co-pilot that’s going to be there across every application canvas, inside of an operating system shell, in a browser.”

An “operating system shell” is a technical term. The shell is the part of the OS that users interact with, on top of the hardware and kernel and below applications. But as Nadella, the CEO of the company that has made more money from operating systems than any other in world history, hints, the OS itself is becoming an empty shell. The action is moving to the browser.

This idea – that we’ll no longer need traditional operating systems, that we’ll just access cloud software through the browser on whichever screen is closest at hand – is what The Browser Company CEO Josh Miller calls ✨ Internet Computers ✨.

In Internet Computer World, you don’t need to download apps on your desktop or your phone. They all live in the browser, and the browser becomes the OS. And unlike Chrome, the world’s most popular browser, the Internet Computer stays in sync across all of your devices. Across any device.

If you want to present on the nearest TV screen, you just log into your Internet Computer and pull up the presentation tab.

If you start a Not Boring essay on your computer and you have to go to work, you can pick up right where you left off on your phone.

The device itself is relatively unimportant in Internet Computer World – it’s commoditized. Anything with a screen and an internet connection will do. “If you smash the computer in front of you right now,” Josh told me, “you wouldn’t lose anything.” The hardware itself becomes the empty shell for the browser; the browser is how you pull all your stuff down from the cloud.

The browser has had an unparalleled thirty year run. While Excel Never Dies, the Browser Keeps Getting Stronger. And now, the stars are aligned for browsers to wipe out traditional operating systems once and for all.

In Differentiation, I wrote:

Things like Replit, Urbit, APIs, and generative AI are only going to accelerate the ease with which people can build something, and exacerbate the challenges for startups building undifferentiated products. Fleshing out where value accrues in this world probably deserves its own post.

This is classic Clayton Christensen stuff, namely The Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits: “The law states that when modularity and commoditization cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.”

I think the value from the app battle will emerge at two stages: below and above. Fierce competition at the app layer will create value that can be captured at the infrastructure layer (below) and interface layer (above).

We’ll talk about the infrastructure layer in another post – think chips, cloud providers, APIs, and protocols – and we’ll focus on the interface layer (above) in this one. “He who controls the interface, controls the universe.”

Just who gets to control the Browser du Jour is another question: The Browser Wars have been fought across decades, in software and courtrooms, among tech’s biggest players. Today, Google Chrome dominates the space, with an absurd 65.7% market share. But every ten years or so, a new Browser War begins, and Nadella’s renewed interest in the browser – Microsoft Edge is a name I’d heard maybe twice in the past five years until a month ago – signifies the beginning of a new Browser War.

The Browser Wars are not for the faint of heart. To win, you need to compete against a three-headed monster of the world’s largest and most powerful tech companies.

The battlefield is littered with smaller foes: Mosaic, Netscape, Mozilla, Opera, Flock. The Browser Company is the latest in a long line of hopefuls.

The new Browser War is such a compelling topic because it hits so many rich veins:

Storied Past: The history of the browser is the history of the internet

Surfing Waves: The browser gains strength from each new tech trend, and the latest, AI, is pulling more activity into it.

Commoditizing Complements: As the battles beneath the browser intensify, it (literally) sits above the fray.

Tech Giant Strategy: Each giant has its obvious strengths and weaknesses that are ripe for Counter Positioning.

An Even Brighter Future: With a new business model, the Internet Computer is potentially the most valuable place in the digital value chain.

There are two big questions to ask here:

Are Internet Computers the Future?

Who Will Build the Winning Internet Computers?

We’ll dive into all of this and more. To start, though, we need to take a very brief pause to set a couple of definitions that will be useful to keep in mind as you read.

Operating Systems and Internet Computers

What is an operating system?

The standard definition is that the operating system (OS) is the software program that manages all of the other applications and processes on your device. An operating system manages the resources of the computer, including memory, processing power, and input/output devices like the keyboard, mouse, screen, and peripherals. To a developer, an OS is a platform they need to build for. Your computer’s OS is probably MacOS or Windows. Your phone’s OS is probably iOS or Android. Developers need to build for each, and the web.

If your OS is working well, you probably don’t think about it much at all. When I think “OS,” the first image that comes to mind is the out-of-the-box MacOS wallpaper – I think of the OS as this thin interface between all of the things going on under the hood in my computer, and all of the things I actually do on my computer.

But if I think about it for another minute, what are the things that I associate with the OS with my user hat on? There are three buckets:

Applications. All of the programs I run on my computer, like Texts and my browser.

Files. All of the things that I save to my computer – like spreadsheets and PDFs.

Utilities. All of the things that I use across the applications and files in my computer, like the Finder file system, WiFi, Spotlight, and System Preferences.

The thing is, with my user hat on, all of the discrete pieces that I think of when I think of an OS have moved, or are moving, to the cloud. The vast majority of applications I use live in the cloud, and even the ones I still have on my desktop pull their content from the cloud. My files live inside my email, Google Drive, or as URLs pointing to the content. I never use Spotlight; my navigation always begins with ⌘+T in The Browser Company’s Arc browser. Give me some WiFi and a browser, and I’m good.

So with that context, what is an Internet Computer?

An Internet Computer is an operating system in the cloud, accessible through the browser across any device with a screen and an internet connection.

All of your data lives in the cloud, all of your files and the applications you use live at URLs, and all of your utilities and preferences live in the browser. Log into the browser, and access everything immediately, right where you left off. With an Internet Computer, the traditional OS just needs to be able to run the browser, and the browser takes care of everything else. The browser is the Last App you’ll need to download.

I’ve been living the proto-Internet Computer life for the past couple of months, since I first spoke with Josh, and it feels surprisingly light. My dock looks like this now:

As soon as Texts.com and Warpcast release web apps, Arc will be the only desktop I keep open. Instead, the apps I use most live inside of the browser.

I can explain the Internet Computer all day, but it’s probably easiest if you try it for yourself. Josh upped my Arc invite limit from the standard five to 10,000, so if you want access to Arc, go download it at this Not Boring link, close out your desktop apps, and move them into your own Internet Computer.

Anyway, I call this the proto-Internet Computer, because for now, it’s limited to desktop. When I use my phone or iPad, I still use discrete apps that I’ve downloaded from the App Store, and access the web through Chrome. I text myself pictures or files from my phone when I need to use them on my computer, or from my computer when I need to use them on my phone. But it’s not hard to imagine popping open Arc Mobile and picking up right where I left off, with everything all in one place.

That’s the vision of the Internet Computer: one thin interface to all of your apps and content on any device.

To me, it seems like the natural endpoint in the evolution of computing (at least until we all have Her in our ears or Neuralinks in our brain).

The Evolution of Computing

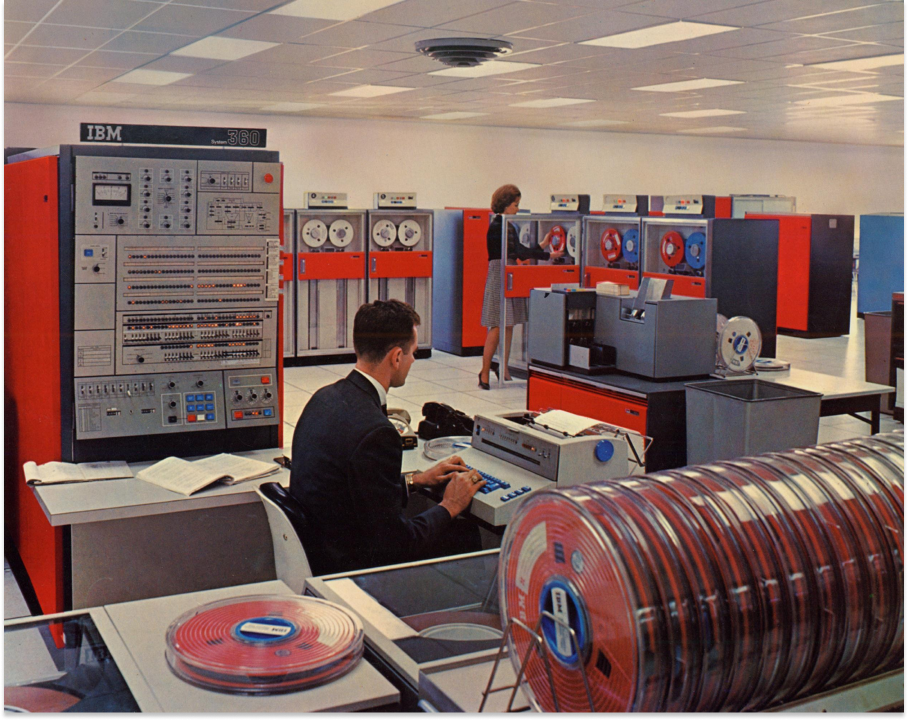

In the beginning was the Mainframe, and the Mainframe was with the businesses, and the business was Mainframe.

Mainframe computers came into existence in the 1930s and 1940s with room-sized monsters like the Harvard Mark I and the ENIAC, but early models were impractical in a number of ways. Like, for example, the fact that each new computer came with a new architecture, which meant that every time companies upgraded their hardware, they had to rewrite their application.

In 1964, IBM spent an eye-popping $5 billion, or $48 billion in today’s dollars, to develop the first mainframe computer system, System/360. That makes Meta’s Metaverse investment seem paltry, particularly considering that IBM generated only half that, $2.5 billion of revenue, in 1962. But the bet paid off. Mainframe computing took the business world by storm. The big innovation was that all of the computers could run the same software, and new hardware no longer meant new applications.

As Computerworld’s Frank Hayes explained, “Hardware compatibility meant platform stability. That led to application longevity, which made complexity possible. A whole new world opened up for IT, a world of huge, business-changing megaprojects.” We owe all of the beautiful, messy, long-lasting, complex software we know and love to the System/360.

Anyway, these mainframe computers sat in a room, and the primary interface was walking up to them and inserting punch cards that told them what programs to execute.

If you want to feel awe and gratitude for the computers we have today, watch this video on mainframe computing from 1964-1972:

Most of us have never interacted with a mainframe computer. We’re used to having our own personal computers. In 1974, MITS released the first personal computer, the Altair 8800. In a fun trivia of computing history, young programmers Paul Allen and Bill Gates got their start by developing the first operating system for the Altair. Microsoft was founded in Albuquerque because that’s where MITS was headquartered.

For a great listen on this story, check out Browser Wars:

I’m not going to spend much time on the dekstop story, because we’ve all heard this one. Microsoft built an operating system that could be used on any personal computer; Apple built Macs with their own operating system that could only be used on Macs.

During the desktop era, computers sat on your desk, and your data lived on-prem, whether inside your personal computer (if you were a personal user) or on company servers (if you were a business user). It was your computer, not a shared mainframe, but as Ben Thompson wrote:

Still, the personal computer, particularly in a corporate environment, lived alongside not just mainframes but increasingly servers on an intranet. The I/O layer and application and data layers were being pulled apart, but both were destinations: you had to go to your desk and be on the network to compute.

Then came the cloud and mobile, the version of computing that most of us use every day.

Initially created as ARPANET in 1969, the internet as we know it today went mainstream in the 1990s, thanks to a battle between Netscape and Microsoft that we’ll get to in a second. While building Netscape, four team members – Marc Andreessen, Ben Horowitz, Tim Howes, and In Sik Rhee – realized that for their customers, setting up a website meant buying expensive hardware and spending IT resources maintaining servers.

So in 1999, they launched Loudcloud, the first cloud services company. It was a hit in the go-go years of the Dot Com Bubble. Instead of buying and maintaining their own servers, internet startups and enterprises could just rent what they needed. But the Dot Com Bubble burst, and cloud didn’t become a major thing until a few years later.

In 2006, Jeff Bezos announced that Amazon would start selling the infrastructure it had built up to run its business to other companies through Amazon Web Services. The next year, Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone.

Fifteen years later, in 2022, AWS did $80.1 billion in revenue, roughly one-third of the cloud infrastructure market, and the iPhone brought in $205.4 billion.

Today, companies host their applications in the cloud and users could access them from anywhere at any time. This is the modern computing paradigm.

Thompson summarized the history of computing to date in one clean image:

“What is notable,” Thompson observed, “is that the current environment appears to be the logical endpoint of all of these changes: from batch-processing to continuous computing, from a terminal in a different room to a phone in your pocket, from a tape drive to data centers all over the globe. In this view the personal computer/on-premises server era was simply a stepping stone between two ends of a clearly defined range.”

Data and applications in the cloud, accessible anywhere, anytime is, according to Thompson, The End of the Beginning.

If we take continuous computing as a given, what will the interfaces of the future look like? Will they, too, be continuous and omnipresent? How will users access all the stuff in the cloud?

This is a battle that’s been raging for three decades.

The Browser Wars

Desktop operating systems and software were good to Bill Gates. By 1995, twenty years into Microsoft’s reign, its co-founder and CEO had become the richest man in the world. That year, Microsoft reported nearly $6 billion in net revenues, and sported a top ten market cap. But the thing that got Microsoft there, he believed, was not going to carry them into the future. The internet would.

On May 26, 1995, Gates wrote a memo to Microsoft’s Executive Staff and direct reports titled Internet Tidal Wave. He opened the memo boldly:

Our vision for the last 20 years can be summarized in a succinct way. We saw that exponential improvements in computer capabilities would make great software quite valuable. Our response was to build an organization to deliver the best software products. In the next 20 years the improvement in computer power will be outpaced by the exponential improvements in communications networks. The combination of these elements will have a fundamental impact on work, learning and play. Great software products will be crucial to delivering the benefits of these advances. Both the variety and volume of the software will increase.

He continued, highlighting the tremendous importance of the internet:

The Internet is at the forefront of all of this and developments on the Internet over the next several years will set the course of our industry for a long time to come. Perhaps you have already seen memos from me or others here about the importance of the Internet. I have gone through several stages of increasing my views of its importance. Now I assign the Internet the highest level of importance. In this memo I want to make clear that our focus on the Internet is crucial to every part of our business. The Internet is the most important single development to come along since the IBM PC was introduced in 1981.

Gates was right to be urgent. The fact was, by 1993, Microsoft was already two years late to the internet.

On January 23, 1993, two students at National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina, released the first user-friendly web browser: Mosaic.

Mosaic wasn’t the first web browser. When they launched, about 1% of the era’s paltry internet traffic went through early browsers for technical users (the rest was mainly text-based in applications like chat and email). But Mosaic introduced a number of features, such as images, clickable hyperlinks, and easy navigation, that opened up the web beyond a handful of hackers and academics.

(Once again, I highly recommend the Browser Wars episode on this).

It was an instant hit. Six months in, it passed 100k users. By the end of the year, it hit 1 million and ~90% browser market share. More importantly, the browser uncorked network effects: as more users surfed the information superhighway, more people and companies created websites for them to use. More websites attracted more users, and so on. This is a common pattern in the Internet Age.

When Andreessen graduated at the end of 1993, he expected to continue running Mosaic to capitalize on the lightning he’d captured. There was just one problem. NCSA owned Mosaic. NCSA’s director offered Andreessen a job on the team, which he quickly turned down. Instead, he headed out to California, where he took a job at a small ecommerce security shop. That didn’t last long.

Down the road, Jim Clark was being pushed out of the company he’d founded: Silicon Graphics. The company, founded in 1982, had seen tremendous success in 3D graphics, particularly in Hollywood (Silicon Valley Graphics were used in Jurassic Park), but by 1994, Clark had developed differences in opinion with management and investors on the company’s direction. So he, too, was out of a job. On his way out, he asked a younger engineer who the best developers out there were, and received a quick response: Marc Andreessen.

So Clark sent Andreessen a quick and fateful email:

Marc:

You may not know me, but I’m the founder and former chairman of Silicon Graphics. As you may have read in the press lately, I’m leaving SGI. I plan to form a new company. I would like to discuss the possibility of your joining me.

Jim Clark.

Marc did know him. He’d been a user and fan of SGI’s machines, and besides, Clark was a legend. They met for breakfast, and by the end, the two men with fresh chips on their shoulders decided to team up. They just weren’t sure on what. Clark wanted to do interactive TV, but Andreessen pushed back: “What we really should do is go do Mosaic right. Do a Mosaic killer.”

On April 4, 1994, they incorporated Mosaic Communications Corporation. The NCSA didn’t like that name, and threatened to sue, so they changed it, and Netscape was born.

The idea for Netscape was simple. Marc would rebuild Mosaic from scratch, but better. They flew to Illinois, met with a bunch of the students who’d helped build Mosaic, and had them sign offers to join Netscape on the spot.

The team built Netscape Navigator from the ground up, improving on errors they’d made as college students hacking something together. Instead of three different code bases for Mac, Windows, and Unix, there was one shared code base. They had fewer bugs. They made it secure, introducing SSL so people could feel comfortable entering credit cards. And they changed up the business model, offering Netscape for free to students and individuals, but charging companies.

It worked. Launched in October 1994, just six months after incorporation, it passed Mosaic in market share by the end of the year. By early 1995, Netscape Navigator had more than 80% of browser market share. Netscape both drove and benefited from the growth of the World Wide Web.

On August 9, 1995, Netscape went public at $28 per share. Its price more than doubled that day, bringing the company’s market cap to $2.9 billion despite its youth and unprofitability, unofficially kicking off the Dot Com Boom. Netscape looked like it was winning a war no one else was fighting.

But even before the company IPO’d, Bill Gates felt the winds changing. That May, he’d written the Internet Tidal Wave Memo. And Microsoft didn’t fuck around. Coming into 1995, its market cap sat at $35 billion, more than 10x larger than Netscape. Now, the internet was priority #1.

On August 16th, 1995, Microsoft released its browser: Internet Explorer 1.0. The First Browser War was on.

Microsoft had two built-in advantages over Netscape: Windows and cash. It began to force computer manufacturers licensed to sell Windows to include Internet Explorer, for free, to users or lose their license. That was a big cudgel, because Windows owned north of 80% of the desktop OS market. It also used its cash to pay companies to use IE. Both AOL and Apple included IE as their default browsers for a time thanks to healthy checks from Redmond, WA.

While IE gained market share, Netscape held them off for a while. After inebriated Microsoft employees dropped a 10 foot tall “e” logo on Netscape’s lawn early one morning in 1997, Netscape employees knocked it over, threw a Mozilla mascot on top, and drew a sign highlighting Netscape’s dominant market share:

Netscape: 72

Microsoft: 18

But it wouldn’t last. By Q4 1998, IE passed Netscape’s market share, and by the turn of the millennium, IE sat far atop the heap with an 80% share.

Whether Microsoft gained that lead legally was another question, and one the US government was particularly interested in asking. In 1998, the Justice Department sued Microsoft for anticompetitive practices, and won the case in 2000, but it was too late. Netscape had sold to AOL for $4.2 billion in 1998, and the combined company couldn’t win back they users they’d losr. Microsoft had won the First Browser War.

It’s worth pausing here to zoom out of the war for a second. When Netscape IPO’d and Microsoft entered the race in 1995, there were 16 million people on the internet. By 2000, that number increased by more than 20x to 361 million internet users.

And during the Dot Com Bubble, generational companies were born on the internet. Amazon and Yahoo! were founded in 1994, eBay in 1995, Rakuten in 1997, Google and PayPal in 1998, Alibaba and MercadoLibre in 1999. The modern internet grew out of the battle between Netscape and Microsoft.

The Browser Wars took a pause in the aftermath of the crash, and Microsoft maintained a 90%+ market share through 2004, when a plucky non-profit’s browser rose from Netscape’s open sourced ashes: Mozilla’s Phoenix, later renamed Firefox.

The Mozilla project launched in 1998 to build on Netscape Navigator’s source code. The goal was to open source browser development and unleash the creativity of developers worldwide. The open source community released Mozilla 1.0 in 2002, but while it counted a number of new and improved features, adoption was minimal. The next year, the project established the non-profit Mozilla Foundation, which directed the project and developed its own software. The Foundation was supported by major tech companies including Google, Yahoo!, IBM, and Intel, all of whom wanted to support a competitor to Microsoft. In 2004, it launched its crack at the browser market: Firefox 1.0.

Where Mozilla 1.0 stalled, Firefox 1.0 caught … fire. Within the first year, the browser was downloaded over 100 million times. Not to date myself, but I remember using early versions of Firefox in college. When I was forced to use IE at work upon graduation, it felt like stepping several years into the past.

Firefox introduced many of the features we’re familiar with in a browser today: pop-up blocking, tabs, and extensions chief among them. It also more closely adhered to web standards than IE, which meant that most web pages worked the way they were supposed to. In my experience, that was not the case on IE at the time.

Riding a better product, the upstart browser ate into, without ever seriously approaching, IE’s dominant market share. By early 2010, Firefox crossed 20% market cap, bringing IE down below 60% for the first time in over a decade.

But Firefox stalled out at 20% and was quickly surpassed by a new browser launched by a friendly face in 2008: Google Chrome.

Google had been a major contributor to Firefox since the founding of the Mozilla Foundation, providing capital, developers, and its V8 JavaScript engine. In return, Google became the default search engine in Firefox for far less than the $300 million per year it reportedly paid in 2014. But by 2008, the Google engineers wanted to do more than they were able to in Firefox.

Darin Fisher, who joined Google to work on Firefox after working at Netscape, told me that one of the big reasons for the switch was multi-processing. Firefox at the time was a single-process browser, meaning that it ran “the browser UI plus the HTML rendering and JavaScript for all tabs in a single process.” That meant slowness, crashes, and security holes.

The Mozilla team, including the Google engineers, all knew that multi-processing – running separate processes for the main browser, the GPU, and each tab and extension – was a superior architecture, but they were stuck. They couldn’t switch to mutli-processing without breaking all of the extensions, so Mozilla went forward with an inferior architecture. Google decided to go its own way and start from scratch.

Chrome was an improvement over Firefox in a number of ways, from the performance afforded by multi-processing to the simplicity of the interface to integrations with Google’s products.

It also introduced the “Omnibox,” the now-familiar search/navigation box. If you knew where you were going, you could enter the URL. If you didn’t, you could search. All in one place.

By early 2012, Chrome had caught up to Firefox’s market share – each had 18% to IE’s 45%. Then in February 2012, Google introduced Chrome for the mobile phone and it rocketed.

By the end of that year, Chrome doubled its market share to over 36% and passed Internet Explorer, which ended the year with 27%.

The Second Browser War ended before it really even began, with Chrome the clear winner. Today, a decade into its reign, it owns 65.7% of the market. The runner-up, Apple’s Safari, has less than one-third the share.

Watch this clip. Seriously, take a second and click the link and watch.

This is what catching the right tech wave looks like, and why all of the giants pour billions of dollars into ensuring they don’t miss the next big platform shift.

You can almost feel where mobile launched in the speed of the Chrome bar’s growth. There are other reasons Chrome won – performance, speed, simplicity, and Google’s marketing heft among them – but those all existed pre-2012. After two decades of intense competition in the Browser Wars, with companies fighting it out over features and performance improvements, Chrome practically floated ahead of the pack by identifying and riding the right wave.

Now, on the back of a number of new waves, and one potentially mobile-sized one, a new Browser War may be beginning. New technologies create new opportunities, and legacy software gets stuck in its legacy ways. Certainly, Satya Nadella has designs on beefing up Microsoft Edge’s capabilities with AI. And new entrants like The Browser Company are taking the opportunity to start with a clean page, like Google did with Chrome when Firefox became too difficult to change.

Because while Netscape, Internet Explorer, and Chrome were portals to the internet from your computer, now might be the right time to start fresh to build the Internet Computer.

Surfing Technological Waves

Thirty years into its life, the browser may be in its strongest position yet. To understand why, you could copy the last three sentences of Bill Gates’ 1995 memo and paste it in a modern one.

The combination of these elements will have a fundamental impact on work, learning and play. Great software products will be crucial to delivering the benefits of these advances. Both the variety and volume of the software will increase.

It’s still true that great software products – browsers, in this case – will be crucial to delivering the benefits of technological advances, and that the variety and volume of software will increase. Only the combination of elements is different.

Today, there are a number of technology trends that strengthen the Internet Computer’s opportunity:

Cloud and SaaS Growth

Rise in Connected Devices

Crypto

AI

There are also two business model shifts underfoot that I think are sneaky good for the browser and make right now an interesting moment for browser disruption:

Ease of Creating New Software and Content

Search Showing Potential Weakness

We’ll go through each in turn, starting with the tech trends.

Cloud and SaaS Growth

“The Cloud” is such a ubiquitous term – one of those ones that shows up in reports from McKinsey and Accenture and whichever consulting firm is trying to sell you IT services – that it’s hard to think of it as a trend anymore. But think about your life over the past twenty-odd years.

Twenty years ago, I listened to music on physical CDs. When iTunes came out, I started downloading songs for $0.99 each to my computer (when I wasn’t downloading them from Napster or Limewire). Now, I listen to everything on Spotify, streamed a la carte.

Fourteen years ago, when I started my career at BAML, I wrote in Microsoft Word, presented in PowerPoint, and modeled in Excel. It was not uncommon to email my MD a pitch deck titled whatever_v17 or whatever_vFinal or whatever_vFinalFINAL. Now, I write in Google Docs, present in Slides or Tome, and model in Sheets or Causal. When I need to send a draft to someone, I just send a link, and when they click, they open up to exactly where the draft stands at that moment. They can even collaborate on it in real time!

You get it. I won’t belabor the point. I’ll just add that this is true not just for people like me, but for huge businesses too. “On-prem” servers are being replaced by cloud services at a rapid rate, even growing off a huge base.

AWS revenue grew from $62 billion in 2021 to $80 billion in 2022, good for 29% YoY growth.

Google Cloud Platform (GCP) revenue grew from $19.2 billion in 2021 to $26.3 billion in 2022, for 37% YoY growth.

Microsoft doesn’t split Azure revenue out from its “Intelligent Cloud” segment, but the company said that Azure grew 31% YoY.

For a category that already generates north of $200 billion in total revenue, roughly 30% annual growth is insane. And the more that applications and data move into the public cloud, the more applications and data are easily accessible from the browser.

Rise in Connected Devices

“Internet of Things” is another category that’s been thought-leadershipped to death, but the fact is that people have more connected devices in their homes than they did even five years ago. Personally, I use a MacBook Pro, iPhone, and iPad, plus a MetaQuest Pro, a screen in the car, two smart TVs, two Alexas, and a Portal. My job is very internet-centric, so I may not be representative, but this Deloitte survey found that the average household has twenty-two connected devices.

Not all of these devices have screens – our Alexas are just voice – but most of them do. And it’s not hard to imagine this number growing as companies race to release AR/VR devices and to bring connected screens into every car.

The world is very different from the world into which the modern browser was born in 1993, when people who were lucky enough to have a computer took turns on the one device that was connected to the internet via dial-up modem. With more devices connected to the internet, there seems to be an opportunity for an Internet Computer that gives you access to everything you have saved in the cloud from any of them.

Crypto

The cloud and connected devices aren’t exactly new trends, they’re just strong continuations of shifts that have been happening for more than a decade. But even newer technologies, like crypto, are largely browser-based phenomena.

While I use mobile wallets, the vast majority of my web3 interactions take place in the browser. When I connect to OnCyber or Uniswap or practically any web3 app, I open up the Metamask Chrome extension, enter my password, sign a transaction, and get kicked back to the main browser, logged in with my entire inventory. I’ve only downloaded one web3 app to my desktop, Warpcast (fka Farcaster app), simply because there isn’t a web app.

Still, the Chrome extension experience leaves much to be desired. Companies like Brave are building browser-native wallets right into the browser, and Brave even introduced its own token, the Basic Attention Token (BAT) in an effort to cut users in on the economy built on the back of their eyeballs.

More broadly, blockchains are decentralized networks of servers, accessible with wallet-based auth from any browser, or Internet Computer, with just a private key. A key part of its beauty is the ability to jump across the internet, from app to app, bringing your inventory and history with you. Crypto’s rise will be a boon to the Internet Computer.

AI

And finally, we have the tech trend du jour: AI.

It’s difficult to see AI as anything but incredibly bullish for the cloud and, in turn, for the Internet Computer.

To start, models are trained in the cloud. To whit, the largest investment in the space to date, Microsoft’s $10 billion investment in Open AI, is as much about OpenAI’s agreement to exclusively use Azure to train models as it is about Microsoft’s willingness to infuse its products with OpenAI’s models. Per Bloomberg:

OpenAI noted on Monday that it uses Microsoft’s cloud-based service Azure to train all of its models and that Microsoft’s investment will allow it to accelerate its independent research. Azure will remain the exclusive cloud provider for OpenAI, the company said. As with Microsoft’s previous investment in OpenAI, much of the value of the deal will take the form of Microsoft giving OpenAI the Azure cloud-computing horsepower needed to run its AI systems, said two people familiar with the deal.

More importantly from the perspective of the Internet Computer, users access AI products and services from their browser. Speaking personally, 99.9% of my generative AI activity has taken place in the friendly confines of Arc – ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, Poe, Lex, Metaphor, Neeva, ExplainPaper, DALL•E, Playground, Elicit, Vana, and all of the other AI apps I’ve experimented with, save Lensa, live in the browser. People built relationships with their Replikas in the browser. Midjourney is kind of an exception; it uses Discord… which I access through the browser.

And this is just the very early days. I expect that we’ll each have AI assistants that travel with us across the internet, providing context and information (like Edge’s AI button) to start, but ultimately learning our behaviors and acting on our behalf, sending emails, writing documents, and doing many of the things that we do manually today.

When that comes to pass, it’s going to be jarring to have AI assistants that only operate in the context of specific desktop or mobile apps, or even within the context of a specific OS. Siri will get smarter, and Bing and Google’s AI assistants will get more powerful, and Notion AI is really good, but my guess is that we’ll want our personal AIs to traverse all of the things we do online, whether on desktop, mobile, or something else, providing context or assistance wherever useful. The best place for such an AI to exist is within the Internet Computer.

Long story short, whichever tech trend you’re bullish on, the Internet Computer is a beneficiary, floating above the fray, not picking favorites, providing access to all.

Browsers are riding tremendously powerful technological waves, but changes in the competitive landscape are equally important to the Internet Computer’s vision.

Ease of Creating New Software and Content

I’ve written a lot about the rise of cloud and SaaS for someone who’s stated that he’s not really investing in SaaS anymore because I think it’s going to be hard (but not impossible for great SaaS investors) to generate venture-scale returns in the category over the next decade. I promise, it’s not as contradictory as it looks; in fact, I think it fits perfectly. Let me explain.

It’s not controversial to say that it’s easier to create great software products today than it was a decade ago. And as something gets easier, more of it happens. “Both the variety and volume of the software will increase.” I think that SaaS is going to be a tough category to invest in not because so few great SaaS products are going to be built, but because so many are! Great software is going to become commoditized.

Here’s why that’s good for the browser’s strategic position: cloud-based SaaS is a complement to the browser (as is internet content more broadly). And as Joel Spolsky wrote in 2002: “Smart companies try to commoditize their products’ complements.”

In the case of the browser, it doesn’t even have to do much to commoditize its complements. It just happens naturally as more hopeful entrepreneurs and hackers compete to build great products in the quest for riches or glory. There are things it can do to help – make it easier to develop web apps, for example – but the commoditization is a natural result of the competition happening beneath the browser’s surface.

It’s hard to capture the power of the tailwinds here without sounding hyperbolic, but I’ll try in two steps.

First, every time an entrepreneur builds a better version of legacy desktop software in the browser – like Figma did with Adobe – the browser benefits. It’s no surprise that the company that currently owns the dominant browser also developed browser-based software that attempted to replace legacy desktop software. Gmail and Google Calendar replace Outlook, Sheets replaces Excel, Docs replaces Word, Slides replaces PowerPoint. Of course, Microsoft responded, and you can access the whole Office Suite in the browser now, too.

Second, the more browser-based software competitors there are, the more opportunities there are for the browser to benefit. Sheets wasn’t the final word for browser-based spreadsheeting. Companies like Airtable, Causal, Rows, and more all compete for your in-browser spreadsheet usage.

This idea is one of the reasons that search engines hold such a strategically important position – they commoditize all of the content on the internet. Instead of seeking out a particular piece of content on a topic, most people head to Google to find whatever the search engine suggests. The App Store and its 30% cut is a good analogue here, too.

Similarly, the commoditization of cloud software means opportunities for browsers. Like websites change themselves to please the search algos – SEO – and apps comply with the App Store’s rules, cloud software may bend itself to better work on the Internet Computer if that’s where all of the eyeballs are.Would apps build in such a way that they’re friendlier to browser-based extensions and AI assistants?

And browsers will power the necessary curation layer on top of all of the cloud software competition. If operating systems have their own app stores, why couldn’t browsers build their own web app stores and take a small cut for turning billions of eyeballs on products locked in competitive battles? More likely, why couldn’t they allow for third-parties to develop a number of app stores, and integrate payments and account management so spinning up a new app is as easy as a couple clicks? When there’s a lot of chaos, there’s a big opportunity for someone to wrangle that chaos, and I think the browser sits in a prime position here, especially with search exposing its soft underbelly for the first time in decades.

Search Showing Potential Weakness

The dirty little secret about browsers is that, for all of their popularity and usage, they’re really just propped up by search revenue.

According to a Bernstein analyst, Google paid Apple $15 billion in 2021 to be the default search in Safari across Apple devices, up from $10 billion in 2020. The analyst expected that number to reach $18-20 billion in 2022.

The two other top browsers - Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge – make their money more directly. Searches within the browsers default to Google and Bing, respectively, and the browser’s parent companies monetize that search traffic.

What if the search business has peaked? While reports of Google’s demise at the hand of OpenAI are likely greatly exaggerated, AI chat’s arrival is the first time that people have begun to seriously question the greatest business model of all time.

I’m not smart enough to know how it will all shake out, but it certainly seems as if the giants are willing to make the cash cow dance for the first time in a long time. Bing introduced chat, and Google announced that they’ll follow suit. Microsoft brought AI into a new-and-improved Edge browser, and it will be interesting to see how Google responds with Chrome.

After ceding browser dominance to Google in the Second Browser War, it seems that Microsoft has gotten its groove back and that it’s ramping up for a Third. What makes this one so fascinating is that each company’s desire to build the Internet Computer will be bounded by their overall company strategy.

Tech Giant Strategy

If you had to bet your entire life savings on one company to create the Internet Computer, you’d be taking a real big risk not to pick Google, Microsoft, or Apple. But before you do that, I suggest you take a beat and think through each company’s strategy and why it may or may not make sense for them to build towards the internet computer. We’ll take them in order of their current browser market share.

Google is a search company.

Sure, it will sell you Google Workspace for as little as $6 per employee per month, and it has a growing cloud business in GCP, but it’s a search company. In the last quarter, $59 billion of its $76 billion in revenue came from advertising, $42 billion of which came from search directly.

Currently, Google is in the lead of the race for the Internet Computer. Chrome has 65.7% browser market share. Its search revenue supports most of the rest of the browser industry. And it’s the first big company to offer a proto-Internet Computer via ChromeOS. On paper, no one is better at capitalizing on more software and content. They need to be taken seriously in this race.

That said, Google is a victim of its own success in a number of ways.

First, search is the greatest business model of all time – Google is one of Ben Thompson’s Super Aggregators. Google is unlikely to make moves that damage search – by making the browser itself smarter with AI, for example. In fact, it’s willing to make the browser experience worse in service of search.

Darin Fisher knows more about building browsers than maybe anyone in the world. He started his career as a software engineer at Netscape, moved to AOL with the acquisition, and then went to Google to build Chrome and ChromeOS. Today, he’s a software engineer at The Browser Company. He explained Google’s mixed up priorities in an interview with The Verge:

Chrome exists in large part to put a search engine front and center, which Fisher describes to me as like “a brick wall” for all kinds of browser innovation. “Anything we did that helps you get back to what you were doing, it means you weren’t searching, right?” Fisher says. Better tab management means less searching; sending you straight to the page you want means fewer search results and fewer ad impressions. Making you close your tabs and reopen them all the time isn’t just acceptable for Chrome; it’s a victory. Fisher and his team had lots of UI ideas and new features, but “all these good ideas die on the floor.”

Even things like Chrome Extensions are limited by prioritizing search. Extensions could be a much richer ecosystem, but Google deemphasizes them because extensions aren’t indexable. It wants you to spend more time on websites.

Things like third-party app stores, curation, and AI-powered recommendations that would make the Internet Computer experience better all lie in direct opposition to the search business.

Second, while Chrome is by far the most popular web browser, its performance is getting worse, and it’s constrained in the changes it can make. Tabs are an issue, but there are a million little things that could and should be improved, but that Google can’t change for a number of reasons. When I spoke to Fisher, he gave me five reasons Chrome was stuck:

Don’t Move the Cheese. Users are used to how Chrome works. For example, they have separate tabs on desktop and mobile. You can’t just make them sync one day without upsetting users who built their own systems on Chrome.

Don’t Break Existing Stuff. Big changes have the potential to break the code and dependencies built up over the past decade and a half.

Inertia. Google just doesn’t move quickly in new directions anymore.

Legacy. Things are done a certain way because that’s how they’ve always been done.

Constraints From Users. With billions of users used to the way Chrome works, any big changes are met with confusion or vitriol.

Third, Google’s culture makes it really hard to take big bets on the core business. If you want to understand why, I highly recommend ex-Google engineer Praveen Seshadri’s The maze is in the mouse:

The way I see it, Google has four core cultural problems. They are all the natural consequences of having a money-printing machine called “Ads” that has kept growing relentlessly every year, hiding all other sins.

(1) no mission, (2) no urgency, (3) delusions of exceptionalism, (4) mismanagement.

Yikes.

You can’t count the leader out, but I would be surprised if Google had what it took to be a real threat in the Internet Computer War.

Apple

Apple is a walled garden devices company rapidly expanding out into services.

The company is hamstrung in the race for the Internet Computer on both fronts.

First, it very much does not believe in a future in which hardware is commoditized and users can access the full power of the cloud on any old thing with a screen. It wants to sell Apple devices. In 2022, $316.2 billion of its $394.3 billion in revenue came from the sale of Products.

Even Safari, its portal to the rest of the internet, is a result of the walled garden approach. Apple devices used to come with Internet Explorer, but the company decided to develop Safari because it wanted greater control over the user experience and to differentiate from other computer manufacturers. With Safari, Apple could tailor the user experience in one of the main areas in which people interact with their Apple devices, and incorporate features specific to the Mac and iOS platforms.

Second, Apple is putting an intense focus on growing services revenue, primarily through the 30% cut it takes in the App Store, and the idea of web apps not intermediated by the app store is antithetical to that pursuit.

While the company has typically prioritized user experience above all else, its insistence on the 30% Apple Tax seems to take precedence today. One of the most frustrating experiences I have online, for example, is that I can’t buy books directly from the Kindle app because Amazon doesn’t want to pay Apple 30% of revenue.

The Internet Computer is a direct threat to Apple’s model. The company is savvy, but I don’t think any organization on the face of planet earth could overcome an innovator’s dilemma this strong. Apple will continue to create premium devices – AR/VR headsets are rumored to be next – and charge premium prices. Tim Cook will be about as enthusiastic about Internet Computers as he was about waving the checkered flag at the United States Grand Prix.

Apple is not a competitor in the Internet Computer War.

Microsoft

Microsoft is an enterprise software and open platform company. They’re happy to let anyone build whatever they want, and sell them cloud and services. If any of the tech giants are going to take the Internet Computer seriously, it’s Microsoft.

After dark years under Steve Ballmer, Satya Nadella’s Microsoft is a different animal. You can see it in the stock price. MSFT underperformed the Nasdaq during Ballmer’s 14 year reign, and Nadella has more than made up for it over the past nine years.

But it’s more than just the stock price. Microsoft is now the strongest of the FAAMGs strategically. Nadella took Microsoft’s core business into the cloud and cross-platform. The company has been friendlier to open source under Nadella. And it’s remained equally ruthless in crushing competitors by copying their best features and bundling them into the core offering. As a former Slack shareholder, I know the pain of Microsoft’s attacks.

It’s also built up an impressive portfolio of future-looking assets, including GitHub and VSCode on the developer side, XBox, Minecraft, and (potentially) Activision Blizzard on the gaming side, and even LinkedIn. As importantly, it’s moved those assets into the future. XBox GamePass is the most successful attempt at the cloud gaming model at which others have tried and failed. GitHub introduced CoPilot before the AI hype got real. And of course, the company has plowed billions of dollars into OpenAI and has been quick to infuse the startup’s magic into its core products.

At the company’s AI event in February, they introduced AI-powered Bing chat, as expected, and even let Sydney run wild for a couple days, which was bold for a company of its size. They also introduced AI directly into the Edge browser, which was less expected.

As Josh Miller summarized in his reaction Voice Memo to Microsoft’s AI announcements, “Satya Nadella is a fucking boss.”

But in the rest of the Voice Memo, Josh lists three reasons he doesn’t think Microsoft’s AI push doesn’t represent an existential threat to The Browser Company:

They used trip planning as a feature example, apparently a sign that they don’t really know what the product is useful for yet.

The UI, interface, and features are too recognizable when something as transformative as Transformers should open up a whole new design space.

“There was no soul or artistic expression, no spirit, no humanity” like there would have been if Steve Jobs or Virgil Abloh were unveiling their LLM product.

All of this boils down to one simple fact: Microsoft is an enterprise company, not a consumer company. They may build the Internet Computer for large enterprises and sell it as part of Microsoft 365, but they may not have what it takes to build products that capture the hearts, minds, and market share of billions of users.

That said, Microsoft is the leading contender among the giants to win the Internet Computer War.

But what if all of the giants are too hampered by their existing products to build a new paradigm?

When I asked Darin Fisher what, given his experience with products like Netscape and Chrome, he would do differently today to avoid getting stuck with a hard-to-turn legacy browser in the future, he paused for a second, and replied: “Maybe you don’t. Maybe that’s success. Firefox was a success, then it got stuck. Then Chrome was a success, and now the same thing is happening. Then the next one comes.”

Enter the next one.

Arc Magic and the Internet Computer

If I personally had to bet – and you gave me odds befitting the tremendous competition it will face – I’d put my money on The Browser Company.

I’ve been a Chrome user for over a decade. Of course, being interested in all things new and shiny, I’ve tried other browsers. Most recently, I tried Mighty because Chrome was just so slow on my old Mac, but I switched back when I got a new MacBook Pro with an M1 chip. Chrome is just familiar.

But a little while back, I heard whispers that Thrive was incubating a new browser. Then I started seeing the teasers from The Browser Company. I got intrigued. I read the announcement post in May 2020. I immediately signed up for the waitlist.

As I waited, and waited, and waited, I followed along as the company teased concepts they were playing with, brought on world-class team members, and welcomed investors who had built leading modern cloud-based companies. Founders and execs at Figma, Notion, Airtable, Stripe, Zoom, Slack, Shopify, Atlassian, and more are all on the cap table.

Finally, last summer, I got access to Arc, and it was better than I was expecting. It was magical.

I wasn’t alone in that opinion. When I asked people on Twitter for the most magical experience they had with a tech product in the past year, Arc came in second behind DALL•E 2 and tied with Stable Diffusion. A browser in the mix with generative AI!

Last September, before I’d ever spoken to Josh or heard of an “Internet Computer,” I wrote my early thoughts on Arc in Indistinguishable from Magic:

I’ve been using Arc for a couple of months, and I don’t have a better way to describe it than “magical.” It’s lighter and faster than Chrome. Ctrl+T feels like a superpower. Screenshots are built in natively and just work without eating all of my data. Downloads appear where they should, and images automagically get saved to an easy-to-find Library. Pinned tabs don’t stare you in the face. Old tabs disappear overnight, clearing space for fresh adventures.

I could go on, but magic isn’t about feature lists, it’s about how those features combine to create a feeling in the user. And two weeks in, I’m still delighted every time I open up Arc.

It’s still very early, and it’s going to be a long time before Arc makes even a small dent in those market share numbers, but I think the company is going to be successful in a way I didn’t previously believe that a browser startup could.

At the time, I thought that Arc was simply building a better browser. I hadn’t put it in the context of cloud growth or connected devices or crypto or AI in my head, although I did write that it might help wrangle all of the chaos as app building became easier: “I think that Arc might be building towards a world in which our online experience is more bespoke, and building an interface that helps its users navigate that world.” I certainly wasn’t thinking about Arc in the context of the Browser Wars; I hadn’t thought much about how frequently the leading browser turned over, or all of the reasons that Chrome would struggle to innovate.

I just thought that the product was magical, and that magic is a reasonable vector of attack for ambitious startups against entrenched incumbents. Chrome was magical, now it’s not. “Old magic fades and clears room for new magic. Abracadabra.”

Now, after talking to Josh and a bunch of other smart people who’ve thought a lot about browsers, I’m more convinced than I was then that Arc has an opportunity to gain meaningful market share in the Third Browser War, and potentially even to win the Internet Computer War.

To believe that, you need to believe two things.

First, that the Internet Computer is going to become a reality. To me, the evidence in its favor is strong. If our data and applications live in the cloud, and if we’re spending more time in the browser, why would the browser not become an operating system?

From the user perspective, having everything in one easy-to-navigate place is a no-brainer. And from the developer perspective, being able to develop a single web app that works across all devices instead of developing iOS apps and desktop apps and Android apps AND paying a tax to Google and Apple makes all the sense in the world. Everyone except the incumbents benefits from the Internet Computer.

When I asked one industry vet what would get in the way of the shift, he replied: “The Internet Computer is inevitable.”

The Internet Computer — the OS in the cloud — has been the Holy Grail in browsers since practically the beginning. There are no app stores in sci-fi. The technology, applications, and content just haven’t been ready… until now.

Second, you need to believe that The Browser Company has what it takes to both capture market share and defend it in arguably the most competitive software segment on earth, against the richest competitors in the world, who have no qualms copying features and leveraging their distribution superpowers. The default assumption has to be that, if there is a Third Browser War, Microsoft or Google will come out on top once again.

With the caveat that I’m a sucker for great products over distribution – I really thought Slack could outcompete Microsoft Teams – I think The Browser Company has a shot.

Start with this assumption: the Internet Computer won’t be built in Chrome as it exists today.

Figma barely worked for me in Chrome – that’s why I switched to Mighty in the first place – not to mention all of the other apps I now happily run in Arc. Assuming that Google figures out Chrome’s performance issues – even Arc is built on Google’s open source Chromium project, the company knows how to build performant browsers – I can’t imagine running my whole digital life from a series of pinned tabs at the top of my browser.

We talked earlier about the fact that Google is incentivized to keep tabs messy – messy tabs mean more searches – but aside from incentives, they’re locked into tabs because their billions of users are used to tabs. Historically, people have lamented changes to the browser, because they’re used to the way their browser is set up, and because changes have meant breaking things. The difference with Arc is illuminating.

With Arc, users celebrate changes. The tweet announcing the last big update – Peek – has gotten over 5,000 likes and 1 million impressions:

There are more examples of Arc update love here, here, here, and more where they came from.

One user even programmed the lights in their room to match the color theme of whichever Arc Space they’re currently in:

Likes are a vanity metric, but there’s a hard-to-measure-but-easy-to-feel buzz around the product that’s very rare. And it speaks to an important advantage Arc has in the battle against incumbents.

Because Arc is currently playing in the “Innovators” segment of that Crossing the Chasm curve, it’s able to experiment freely without upsetting users. Experimentation is exactly what its users are looking for! They’re looking for an adventure, for magic.

If the Internet Computer requires a fresh approach to the browser, that license to rethink everything can’t be overstated. When I asked Darin how the team decides which new features to add, he told me they ask, “Does it bring people joy? Does it make them happy? Does it tickle them?” I doubt those are the questions being asked at Google.

The more Arc pushes the boundaries, the more people talk about it and share it with friends, the more it grows. Josh shared a graph showing the number of people using Arc at least 5 days per week (although he didn’t share actual numbers) and the slope is steepening.

Whatever the number, it’s a tiny blip on the browser market share radar, but if you use all 10k of my Arc Gifts, it’ll steepen even more.

But as Slack will tell you, getting innovators and early adopters to use your product is only half the battle. Crossing the chasm and retaining users in the face of an attack from Google and Microsoft is a different story altogether.

Here, I think Figma is instructive. In Why Figma Wins, Kevin Kwok wrote:

Companies are a sequencing of loops. While it’s possible to stumble into an initial core loop that works, the companies that are successful in the long term are the ones that can repeatedly find the next loop.

The Browser Company is currently in that initial core loop that works. It’s winning on being cloud-first and by building better tech. To move to the next level and build real defensibility into the business, it will need to move to the next loops. The two that Kwok identified for Figma – enterprise sales and cross-side network effects – both make sense for The Browser Company, too.

In both cases, it will need to innovate on the multiplayer experience. Companies should be able to get more work done more efficiently when more of their employees use Arc. And Arc users should be able to collaborate with each other – and with their AI assistants – across the entire internet, like Figma for everything. I’ve long wanted to see someone bring back Genius’ vision of a user-annotated internet, and that seems like an example of something that could be built in Arc.

Beyond that, just as Figma has a rich ecosystems of plugins, Arc will need to become a platform on top of which people build. That might be as straightforwardly analogous as more people creating Boosts – Arc’s more fully-featured version of Chrome extensions – or it might mean a variety of third-party web app stores designed to curate the overwhelming number of incredible new cloud apps. Certainly, it will mean tools for developers to build web apps designed with the Internet Computer in mind.

First things first, though, it means showing users the power of the Internet Computer by introducing Arc mobile. Today, Arc is just a much better browser experience. But with mobile, which should be coming soon, I’ll be able to log into Arc from anywhere and tap into the intentionally-designed Spaces I’ve set up over the past few months.

That said, launching a mobile app and winning mobile market share, not just from other browsers but from the apps we’re all accustomed to using on our phones, are two different stories. The beauty of apps is that they’re just one click away. By definition, in a mobile browser, they’re at least two clicks away. There will be a million design challenges in making the mobile window to the Internet Computer feel as native and seamless as apps.

For a company dedicated to “eliminating paper cuts” – finding those annoying things about using the internet and knocking them out one at a time – it’s not an insurmountable challenge, but it’s a challenge nonetheless.

Then there’s the unavoidable fact that in order to take down Apple’s App Store monarchy, The Browser Company will have to go through… Apple’s App Store. Tim Cook & Co. are not going to roll over easily, as their willingness to battle Epic, Spotify, Amazon, and any app maker brave enough to try to defy them proves. Apple not only has premium branding and a tightly-integrated ecosystem, it has the best in-house silicon and most performant devices in the game. It’s easy to envision a post-App Store world in which the Internet Computer has won – it makes sense in a lot of ways – but things get more complicated when you think through the path from here to there.

Nobody said this was going to be easy. They call them Browser Wars for a reason. Tech’s biggest players have spent billions of dollars and gone to the brink of Antitrust Armageddon in order to control users’ access to the internet. And if the Internet Computer vision is true, if practically everything goes through the browser, the stakes are even higher now than they were then. As the browser’s business model evolves from “top of funnel for search” to something richer and more integrated, trillions of dollars are at stake. This war may be proportionally bloodier than the last two.

But it’s worth the fight. Everything is moving to the cloud. AI will live in the browser. Billions more users will come online. The competition among app developers, content creators, and even hardware manufacturers will be intense, causing commodification that presents an opportunity for value capture at the interface layer.

Whichever company wins the Third Browser War – The Internet Computer War – will have secured what is potentially the most valuable real estate in the history of the internet.

Let the games begin.

Thanks to Josh and Darin for your input, and to Dan for editing!

That’s all for today! We’ll be back in your podcast feeds this week and your inbox on Friday for that Weekly Dose of Optimism.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Okay, this article was magical... Arc has completely taken over my mind space since initially getting access. With what I thought Chrome and ChromeOS would one day be (the internet machine), after exclusively using ChromeOS for 6 years to make a point (that even 99% of running a technical software integration company, was achievable in the browser alone). I realized though after using Arc exactly why Chrome OS and Chrome will never be that. Selling my Chromebook and buying my first MacBook Air, never to look back at Chrome/ChromeOS again.

Seeing Darin join TBC and the reasonings behind it resonated so strongly, my past decade of hope summarized in such few words from Darin's mouth, and you did such an amazing job of capturing it all of this and more in this piece. Well done 👏

It's funny, in also trying to explain to people what makes Arc magical, I couldn't help but write a couple months after first discovering Arc, a 4,400 word article on the magic of Arc through my ChromeOS and extension journey: https://efficientvc.substack.com/p/conviction

I genuinely think it's one of those iPhone moments. You either install it, use it for a few days, and "get it", or you judge it from afar. All I know for certain is that we haven't seen something as magical as Arc in a while. In the vision of what it'll be, not just what it is today.

While I love and invest into SaaS, Arc is one of the first times that the vision of what it could be is so much larger than anything else out there. So how can any of us really get this point across? We've tried, we'll keep trying, but at the end of the day, people will ultimately see.

Amazing Piece Packy 🔥🔥🔥

Counter intuitive though it may seem, part of this is likely to work flipped on its head:

“ultimately learning our behaviors and acting on our behalf, sending emails, writing documents, and doing many of the things that we do manually today.

When that comes to pass, it’s going to be jarring to have AI assistants that only operate in the context of specific desktop or mobile apps, or even within the context of a specific OS. Siri will get smarter, and Bing and Google’s AI assistants will get more powerful, and Notion AI is really good, but my guess is that we’ll want our personal AIs to traverse all of the things we do online, whether on desktop, mobile, or something else, providing context or assistance wherever useful. The best place for such an AI to exist is within the Internet Computer.”

The perception that applications are personalized to us when instead they only need understand our context and how that context relates (web of relations) to other entities.

Similarinc.com is developing exactly that data set outside of applications, ergo cross domain. Don’t rule out the browser extensions from the browser opportunity just yet!