The Interface Phase

We shape our interfaces; thereafter, they shape us.

Welcome to the 3,188 newly Not Boring people who have joined us over the last two weeks! Join 75,787 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Sprig

Sprig is a long-time sponsor (you know it as UserLeap), but the team added so much to its products that it needed a new name: Sprig.

Sprig is your all-in-one product research platform. Every week, at the bottom of the newsletter, I use a Sprig microsurvey to get your feedback -- you click a button to tell me whether you loved or hated the newsletter and write a comment, and Sprig categorizes responses with machine learning so that I can get a quick pulse check.

Recently, Sprig rolled out two new solutions: video interviews and concept testing. Now, companies can have async video conversations with users, and can even share Figma designs at the same time to get rich feedback on concepts and prototypes that are still in development. If you build products, you should just try it for yourself.

Sprig is addictive. I check it at least once a day. I love reading what you write, even when it hurts. And teams at Opendoor, Loom, and Dropbox love UserLeap too. The Sprig team knows that once teams start using it, they don’t stop, so it’s offering a free onboarding and 30-day trial to any enterprise company (~100,000+ users).

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday! Football is back, it’s Fall in NYC, and life is good.

This one is a little shorter than the average Not Boring. Spend the extra 15 minutes enjoying a nice cup of coffee, hanging with your family, or outside taking a walk. I’m excited for richer digital spaces, but at the expense of less rich digital spaces, not good ol’ fashioned IRL time.

Let’s get to it.

The Interface Phase

Horseshoe or rectangle?

In October 1943, two years after bombs destroyed the British Parliament’s Commons Chamber in the Blitz of 1941, the House of Lords debated how to rebuild. Some MPs and Lords wanted to take the opportunity to rearrange the Chamber in a horseshoe style, like the US Senate and House of Representatives.

Others argued that they should retain the “adversarial rectangular pattern” from before the bombing. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill led team rectangle. Churchill believed that the layout of the space itself was responsible for the British two-party system. The confrontational design -- with the Conservative Party on one side and the Labour Party directly across from them -- kept debates “lively and robust.” The design left no space for equivocation. You’re with us, or you’re directly against us.

In his October 28, 1943 speech on the matter, Churchill delivered an all-time classic line:

We shape our buildings; thereafter, they shape us.

Churchill and his rectangle side won the day. To this day, Members of Parliament can only switch allegiances by physically crossing the floor in plain view.

We shape our buildings; thereafter, they shape us. The spaces in which we live, work, and play shape how we live, work, and play. Churchill was referring to physical buildings, of course. The state of the art computer at the time was Colossus, which Alan Turing and team used to break Axis codes during World War II. Its interface was a series of switches and dials. Only a few people in the world needed to, or knew how to, operate it.

Increasingly, though, the spaces in which we spend time are digital ones.

Each new phase of the internet -- Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Mobile -- relied on new digital spaces to attract consumers. From text-based to graphical to interactive to mobile apps, new interfaces brought new adoption. Each phase was enabled by new infrastructure beneath the surface and pushed to popularity by the apps built on top, but each also required new interfaces to achieve broad adoption.

We shape our interfaces; thereafter, they shape us.

While web3 apps like NFTs, DAOs, and DeFi are gaining popularity, we’re still interacting with web3 through web2 interfaces. If history is a guide, we’re going to need new web3-native interfaces and spaces to bring hundreds of millions of people into the ecosystem.

It’s early, but there are clues of what new interfaces might look like. New digital spaces are springing up around the internet and evolving every day. Wallets like MetaMask, Phantom, and Rainbow are changing how we log in, and what we bring with us when we do. Web3 worlds like Decentraland, Somnium Space, The Sandbox, and Cyber are reimagining how we experience and interact online. They’re early components of the Metaverse, sure, but this isn’t necessarily a Metaverse piece. It’s a piece about the evolution of the way that we interact with, and on, the internet.

We’ve spent most of 2021 over here at Not Boring HQ exploring web3, and hopefully we all understand what’s happening a little bit better because of it, but it’s still hard to feel the potential impact of web3 in our bones while we’re still using web2 interfaces. For web3 to become a part of our daily life in the way that the internet or mobile is will require new spaces and interfaces.

Today, we’ll explore how those new interfaces and spaces might bring web3 mainstream:

The Apps-Infrastructure Cycle

An Incomplete History of Interface SuperCycles

Web3 Interfaces

Into the Future

The cheat code for studying new technologies is that they tend to follow old patterns. Let’s look back before we look forward.

The Apps-Infrastructure Cycle

A common narrative in the Web 3.0 community is that we are in an infrastructure phase and the right thing to be working on right now is building out that infrastructure: better base chains, better interchain interoperability, better clients, wallets and browsers. The rationale is: first we need tools that make it easy to build and use apps that run on blockchains, and once we have those tools, then we can get started building those apps.

- Dani Grant & Nick Grossman, The Myth of the Infrastructure Phase, USV, 2018

In 2018, Union Square Ventures’ Nick Grossman and Dani Grant wrote an essay called The Myth of the Infrastructure Phase. During 2018’s crypto winter, they kept hearing that crypto needed better infrastructure, and once that happened, then people would be able to build those killer apps. People building infrastructure, though, said that they were building the infrastructure, but that no one was building apps on top! Why the disconnect?

Instead of the commonly-accepted “infrastructure phase,” Grossman and Grant argued, crypto was in another turn of the apps-infrastructure-cycle. “The history of new technologies shows that apps beget infrastructure,” they wrote, “not the other way around.”

First, builders build apps, then other builders build the infrastructure to support those apps, then that infrastructure supports new apps, which in turn requires new supporting infrastructure, and so on. That’s how it worked historically, from the lightbulb to the airplane to the iPhone, and it’s exactly what was happening in web3.

Grant and Grossman’s 2018 classic has re-entered the conversation recently, as an explosion of new web3 apps has caused challenges:

Gas prices are too high!

DAOs coordinated across a mishmash of tools.

Delayed Eth2 and L2 confusion.

Scams abound.

Speculation reigns and the rich get richer.

Last week, Paxos Global and 6th Man Ventures’ Mike Dudas tweeted that the piece was very relevant to the current crypto environment. Blockchain Capital’s Kinjal Shah tweeted, “we’re in an app frenzy, about to enter a major infrastructure phase.”

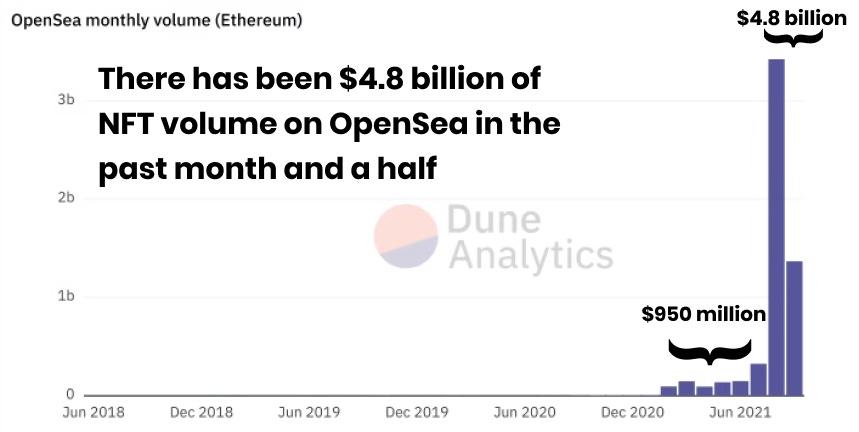

The apps-infrastructure cycle is playing out in real-time. For example, Grant and Grossman mentioned ERC721 as the last piece of infrastructure built when they wrote the piece. The 2018 invention of ERC721, the non-fungible token standard (infrastructure), has powered the 2021 NFT craze (app). From February to July, $950 million worth of NFTs changed hands on OpenSea. In August and the first 12 days of September alone, $4.8 billion has passed through OpenSea.

As a result of all this demand, cracks in the infrastructure are showing. Gas fees, the price someone needs to pay to Ethereum miners just to buy or mint an NFT, regularly cross into the $300+ price range during a hot drop. Already, builders are deploying new infrastructure to fix the problem.

New Layer 2 scaling solutions will continue to improve speeds and lower transaction costs. Arbitrum, a new L2, launched on Ethereum Mainnet in early September and its parent, Offchain Labs, announced a $120 million round led by Lightspeed. In the past 24 hours, 14,260 ETH have been bridged from Ethereum to Arbitrum. The bridges from Ethereum to L2s, like Polygon, Arbitrum, Fantom, and Optimism, and other L1s, like Solana, Avalanche, and Near are open and flowing. Polygon is leading the charge, with $2.4 billion in Total Value Locked (TVL), a proxy for volume.

But while the infrastructure will continue to improve, the bigger challenge right now is the fact that we’re interacting with web3 products via Web 2.0 interfaces.

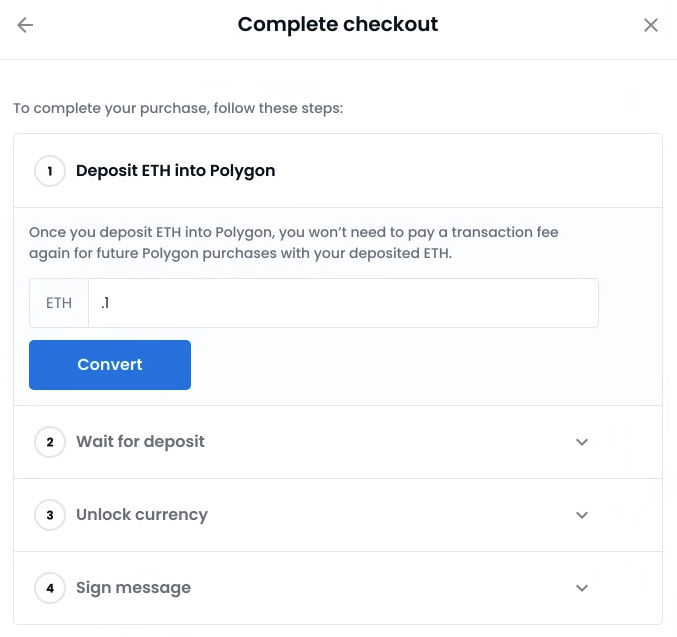

Some NFTs are already available on OpenSea via Polygon, on which transaction fees are much lower, but that requires “bridging” your ETH over to Polygon (which costs gas), waiting nervously for the deposit to go through, unlocking your Polygon ETH, then signing a message to complete the transaction.

I am fairly comfortable with all of this, and it still gives me pause. (That said, 250k people have participated in at least one OpenSea Polygon transaction. Maybe I’m a luddite.) The infrastructure is getting there; the interfaces need a refresh.

This isn’t a knock on OpenSea. OpenSea is killing it, and I’m a big fan. It just crossed 400k total traders all-time. It’s made it possible for a large number of early adopters to buy and trade NFTs. But it still looks and behaves like a web2 product, as most web3 products do. People upload content, other people can interact with and transact that content. The infrastructure behind OpenSea is novel, and OpenSea abstracts away a bunch of complexity, but the OpenSea interface could have been built in 2015 or even 2010. eBay has been around since 1995.

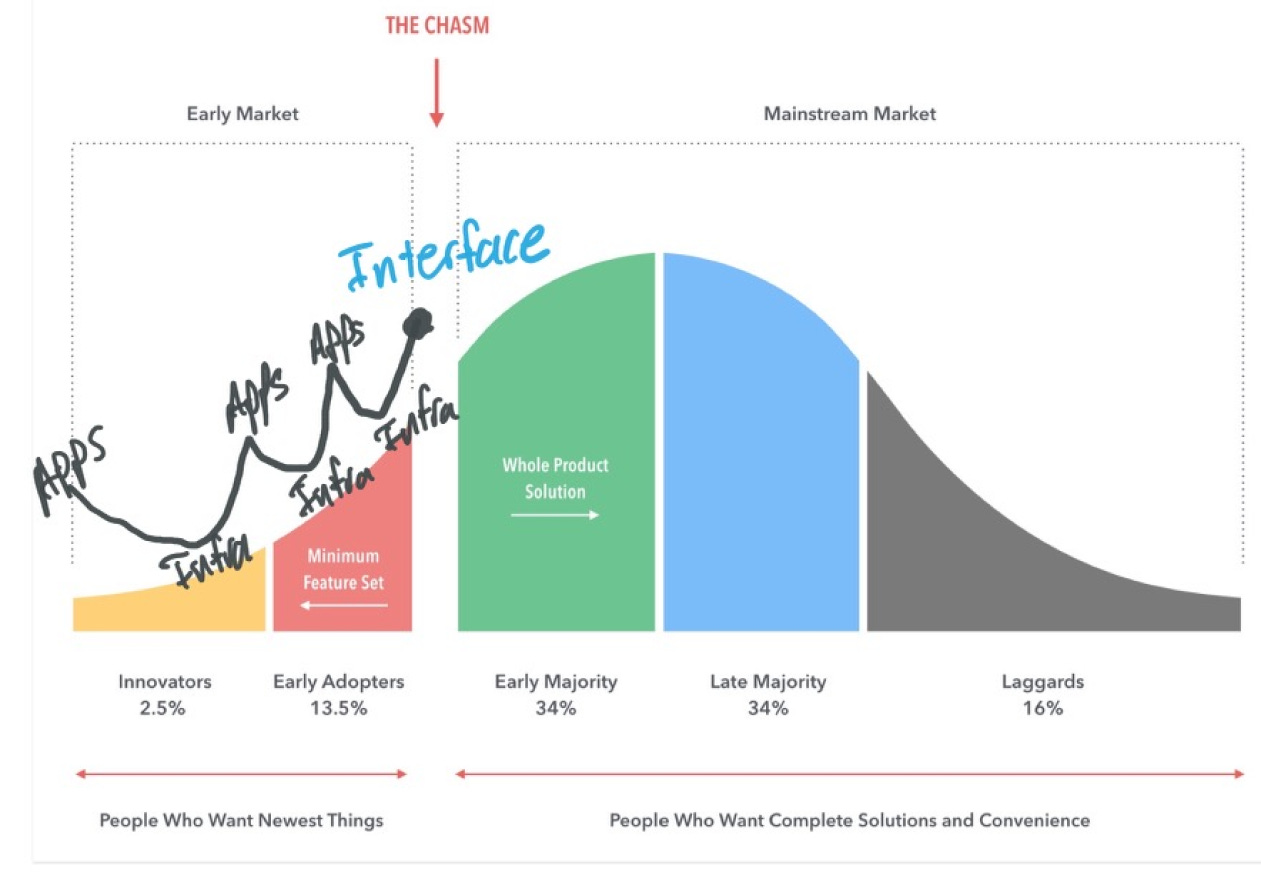

It’s still so early. If web3 is going to be as big as the internet, which has 4.66 billion users, it’s only penetrated less than 1% of the market as judged by the number of people who have MetaMask wallets (which just passed 10 million). There’s still a lot of work to be done to attract a broader base of early adopters, and even “Cross the Chasm” to the early majority.

We’ve discussed some of the things that will accelerate the adoption of web3 technology in the last few posts, and we’re adding another concept today:

L2s and other Layer 1 blockchains like Solana, which offer faster speeds and lower costs than Ethereum and Bitcoin, and feel more like the regular internet, will bring new developers onto the blockchain, who in turn will bring more users.

Corporates will bring their customers into web3 in more consumer-friendly and familiar ways, such as letting them buy NFTs with a credit card or using social tokens to reward loyalty and encourage certain behaviors like attending live events.

More entrepreneurs will choose to build their next thing in web3, and some early stage companies might pivot or figure out how to incorporate things like tokens and NFTs.

Apps-Infrastructure Cycle: Better apps will lead to better infrastructure will lead to better apps will lead to better infrastructure in the ongoing apps-infrastructure cycle.

But there’s still a missing ingredient, at least based on the last three major consumer internet paradigm shifts: new epochs need new interfaces.

An Incomplete History of Interface Cycles

What we think of as the internet dates back to the Cold War, when the US Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) developed what would become ARPANET so that the US military could communicate over a connected, distributed network.

Mike Murphy’s 2019 Quartz piece, From Dial-Up to 5G, a complete guide to logging on to the internet, describes the history of the internet from ARPANET to mobile, with a brief glimpse into the 5G future. Murphy explains that over the internet’s first three decades, it remained a tool for academics, the military, and some nerdy tinkerers. By the time I was born in 1987, schools in 25 countries were connected to ARPANET, and the military had branched off to its own version, MILNET.

Businesses and more technical civilians started coming online in the late 80s and early 90s (Internet Relay Chat, the predecessor to Slack and Discord launched in 1988), but it was tough to use. This 1993 video, The Computer Chronicles - The Internet, is a funny time capsule. It reminds me of my first interaction with computers via floppy disks, chunky keyboards, and blinking command-line interfaces.

To use the internet in the early 1990s, you really had to know exactly what you were looking for and specifically how to search for it in the command line. In Before the Web: The Internet in 1991, ZDNet’s Steven J. Vaughan Nichols agreed:“The pre-Web Internet was an almost entirely text-based world...If this makes the pre-Web sound like a place that was only welcoming to techies in those days, you're right, it was.” (Sounds familiar.)

Then, in 1993, Marc Andreessen built Mosaic at NCSA, and quit to build his own competitor: Netscape. “Before Netscape Navigator, the internet was an abstract concept, used primarily by the military and academia,” wrote Alice Truong in a 2015 Quartz piece commemorating 20 years since Netscape’s 1995 IPO, “but Netscape’s graphical interface made the web accessible to everyday people.”

While internet service providers like AOL, Prodigy, and Earthlink brought people online into their controlled portals, Netscape gave people access to the open World Wide Web and ushered in the Web 1.0 era for the masses. There had been improvements on both the app and infrastructure side over the previous three decades -- better computers, faster dial-up, email, IRC, the first website and first web browser (both built by Tim Berners-Lee) -- which a small group of technical users used, but it was Netscape’s graphical interface that pulled people into Web 1.0 in droves. Tens of millions of people could surf static web pages on the “read-only” web.

In 1995, when Netscape went public, there were 16 million internet users in the entire world. By 2000, just five years later, there were 361 million internet users. By the time Mark Zuckerberg launched Facebook in his dorm room in February 2004, there were 745 million people on the internet. By the end of the next year, there were a billion.

If Web 1.0 was the “read-only” era of the web, Web 2.0 was its “read-write” era. It turned the internet from a static book to a live canvas on which users could express themselves and interact with people around the world in real-time. The same app-infrastructure-interface cycle played out on Web 2.0.

Demand for Web 1.0 apps caused the creation of the infrastructure that made Web 2.0 possible. Right around the turn of the new millennium, the internet began to catch fire. Brian McCullough wrote in TED

that:

Before the bubble burst, telecom companies raised $1.6 trillion on Wall Street and floated $600 billion in bonds to crisscross the country in digital infrastructure. These 80.2 million miles of fiber optic cable represented fully 76 percent of the total base digital wiring installed in the United States up to that point in history and would allow for the maturation of the internet.

Fiber optic cables opened the door to faster, more reliable internet (and allowed people to use the phone and the internet at the same time!). WiFi, which Apple first included in laptops in 1999, freed internet users from the restraints of ethernet cables. The infrastructure to power an always-on web was coming together.

At the same time, on the app side, Blogger and LiveJournal, both founded in 1999, let regular users start putting their thoughts on the internet without needing to learn how to code, and MySpace’s 2003 launch added friendships to the mix. Facebook launched in February 2004, and rolled out the Wall in September of that year, with static pages on which users could put one picture and some basic information about themselves for classmates to see.

Digg launched in November 2004 and gave users the ability to submit and upvote content. YouTube launched a year later, in 2005, allowing users to upload, search for, and rate videos. Meanwhile, Facebook kept pushing -- dropping photo tagging in 2005, the News Feed in 2006, and the Like button in 2007. Twitter launched in 2006. Web 2.0 was here to stay.

While Blogger and MySpace were proto-Web2.0 apps, only a small handful of people wrote blogs, and MySpace only reached a peak of a little over 100 million users. The real-time, interactive interfaces of Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and other social networks popularized Web 2.0 and pushed it across the chasm. Today, Facebook has over 2 billion users.

The last major paradigm shift before web3 was mobile. Internet on the phone dates back to the Wireless Application Protocol (WAP), which was introduced in 1999. The Nokia 7110, released October of that year, gave its owners a rudimentary ability to do things like check sports scores, headlines, or weather (apps), but it burned tons of expensive data in the process. As wireless coverage and speeds improved, data rates came down, and 3G rolled out in 2003 (infrastructure improvements) mobile phone makers began offering slightly-less-basic mobile browsers. But without Apple’s 2007 iPhone release and 2008 iPhone App Store launch (and Android’s subsequent Play Store), mobile internet would likely not have become ubiquitous.

Mobile Apps were a new interface native to the new mobile computing platform. Without Apps, it’s hard to imagine the success of mobile-first products like Uber, Snap, or even Twitter and Facebook. Accessing any of those products through a mobile web browser, even today, is a deeply sub-par experience. Mass users need new interfaces to adopt new computing platforms.

web3 is next. It’s now been over twelve years since Satoshi Nakamoto launched the bitcoin network by defining the genesis block.

Since then, over a trillion dollars worth of value has been created. Roughly 100 million people worldwide own BTC. 56 million people use Coinbase. 10 million people have a Metamask wallet. DeFi and NFTs have seen tremendous surges in adoption among innovators and some early adopters over the past two years. More demand from popular apps has spurred innovation on the infrastructure side, with new Layer 1s, Layer 2s, and protocols racing to fix problems and improve user experiences.

That said, the web3 experience still remains complex and confusing to all but the most technical or committed. By baking money into the protocols themselves, web3 has been able to bootstrap demand further ahead of user experience than the paradigms of the past, but that won’t be enough to cross the chasm. At best, if you count “Bitcoin ownership,” often through a centralized exchange or a product like Square, as web3 adoption, we’re at MySpace usage levels. At worst, if you believe that web3 usage means interacting with a wallet, we’re near 1995 internet adoption levels.

The internet seems to go through not just apps-infrastructure cycles, but apps-infrastructure-interface supercycles. After enough app and infrastructure iteration to prove early demand for a new paradigm, a new interface is needed to bring it across the chasm.

That’s where we are now. web3 needs web3 interfaces.

Web3 Interfaces

First, we shape our interfaces; thereafter they shape us.

Web 1.0: The graphical browser made it easy for regular people to surf the web, and led to an explosion of the “read-only” websites that created the dot com boom.

Web 2.0: Interactive, real-time websites made it easy for regular people to connect, communicate, and create online.

Mobile: Apps made it easy for regular people to do everything from their phones. From calling a car to making payments to playing games to working, “there’s an app for that.”

The spaces, physical and digital, in which and with which we interact shape our experience.

So what will the breakthrough web3 interface look like? What will it let people do?

Paradigm-shifting interfaces do a few things:

Abstract away complexity

Give users easy ways to take advantage of most of the power of the new tech and assets

Wrangle some of the entropy created by the new tech

Create new experiences not possible through previous interfaces

The web3 interface will need to add order to the beautiful chaos of decentralization, and give obvious and meaningful utility to digital assets. It will need to break the false dichotomy between easy, consumer-friendly on-ramps and a powerful crypto-native experience. It will need to wrap itself around the apps and infrastructure that have been built to date, hide complexity beneath the surface, and deliver clean experiences. It will need to create a canvas for both developers and users themselves to create the next million new apps.

At first, web3 experiences will be largely desktop based. As the infrastructure catches up, I suspect that there will be a seamless mix of desktop, mobile, VR, and AR, a game-like interface that persists and carries across mediums. VR will steal share from desktop and AR will steal share from mobile, as both AR and VR will be capable of richer experiences and will make NFTs feel more “real.”

Ultimately, it will need to provide experiences that are so much different and better than what people are able to get from the normal internet that they’ll want to make the leap, even if it means a little bit of friction.

Let’s explore some possibilities.

Wallet-First

web3 starts with the wallet.

Wallets are passports and bank accounts. They serve as users’ identity, and lets them carry their digital assets across web3. Signing in on web3 means connecting your wallet, and once you’re connected, you can spend, trade, and gain access to gated areas. My three favorites are MetaMask (for Ethereum browser sign-in), Rainbow (for iOS and for searching wallets), and Phantom (for Solana browser sign-in). If you don’t already, go get one of each; you’ll need them.

In New Internet Logic, PartyDAO’s John Palmer wrote that with NFTs:

The internet is now a place where everyone has an inventory. The existence of programmable, interoperable digital objects will fundamentally change the logic of the Internet.

What does that mean?

When I log into a normal website, that website knows what I’ve done on that website before. When I log into Amazon, for example, Amazon knows what I’ve bought on Amazon, which credit cards I use to buy things on Amazon, and the address to which I want Amazon to send the things I buy. It doesn’t know about what I own elsewhere. It can only really design experiences for me based on my Amazon activity.

When you sign in with your crypto wallet, though, the site knows whatever you hold in that particular wallet, and can give you permissions and experiences based on what you bring with you. Last night, I found a new project that looks incredibly simple but points to one of the ways that wallet-first interfaces might work: Playground.

I’d never been to the site before, but as soon as I connected my MetaMask, it knew which NFTs I owned, and gave me access to chats with other people who own those NFTs. Already, Discord servers use Collab.Land to grant access based on whether or not people hold certain tokens, like $FWB, or specific NFTs, like Loot bags with divine items. In those cases, owners need to seek out and access communities one-by-one; what’s so interesting about Playground is that it does the work for you, creating communities for all NFT holders. This is obviously not the design of the future, but it holds the seeds of a subtly important shift in the way we interact with web3. Discovery is going to be important as more new NFTs, DAOS, and tokenized communities spring up every day.

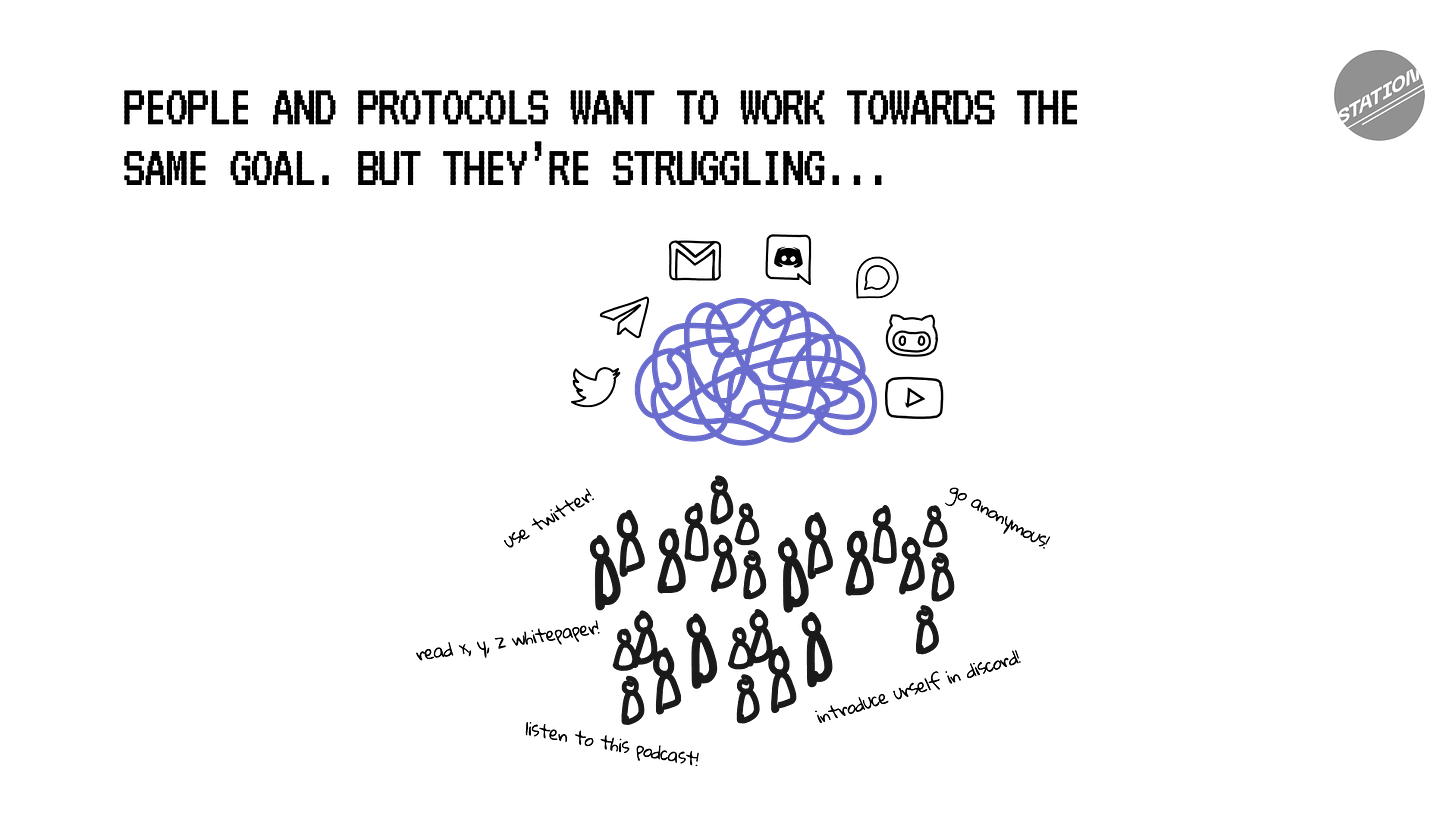

In its launch announcement, Station, one of the web3 projects I’m most excited about, highlighted how difficult it can be to navigate web3:

This infrastructure does not currently exist for crypto. It’s currently extremely difficult for newcomers, especially if they are not technologists themselves, to navigate the ecosystem, quilted together across Discord servers and Telegram group chats.

Station plans to add to a person’s web3 identity, not just based on what you own, like a wallet, but what you contribute and who you interact with. “Everyone will have a Profile on Station that aggregates their Contributions across platforms, their on-chain interactions, the groups they represent, and their closest collaborators,” the team wrote. It’s not hard to imagine that Profiles might serve as another wallet-like building block for a new web3 interface that takes you where your skills are needed most.

Wallets and Profiles will serve an important role in the web3 interface. It’s likely that one of the existing wallets, or a new company like Crucible, will roll up multiple wallets and Profiles into one Decentralized Identifier that lets a user bring his or her activity, contributions, relationships, and inventory from across chains with them wherever they go.

The point here is to abstract away complexity and let users roam freely across web3. While I think any solution that avoids users controlling their assets in a portable way is unlikely to ultimately win, winning solutions will make doing so as easy as possible.

But what are we going to be accessing with our wallets and profiles? Where will we be carrying our assets and on-chain history?

Let’s jump into the Metaverse.

3D Spaces and Worlds

One of the things that crypto is good at is giving digital assets physical characteristics.

Cryptocurrencies behave more like cash than bank-mediated digital money. They’re peer-to-peer, and if I sent someone 1 ETH, that ETH goes right from my wallet to theirs.

NFTs make digital items unique, ownable, and scarce, like physical items.

I believe that the web3 interface, then, will be something that also has more physical characteristics than the internet we’re used to. Before going deep into web3, I thought that digital worlds and web3 were two separate ideas that should interact. Now, I think that digital worlds are necessary to unlock the full value of web3, and that web3 is necessary to unlock the value of digital worlds.

The web3 interface will be digital worlds accessed via wallets.

Video games are a good and obvious comparison. People spend billions of dollars on virtual items, skins, and dance moves in games, but they can’t take those virtual items with them outside of the game world. The web3 interface will be rich, immersive environments in which most things are ownable, earnable, and transferable across worlds. Digital worlds are the only interface in which all of this ultimately makes sense, and creating those rich digital worlds that require and reward ownership and contribution is how web3 will onboard the next billion people.

As Matthew Ball has eloquently written, a lot needs to happen on both the apps and infrastructure side, for the Metaverse to reach its full form, and certainly many of today’s Metaverse-like worlds are clunky and toy-like, but there are early signs of how it will work.

My current favorite is Cyber. Cyber gives NFT owners 3D galleries in which to display their digital art and audio. Collectors don’t need to buy land in a virtual world to get started, and Cyber offers simple spaces for free, but they also let 3D architects design and sell upgraded spaces for collectors who want to give their NFTs more stunning homes.

Cyber takes a principled stand on ownership. Everything inside of the gallery is an NFT. All of the art on the walls or statues or even the music playing in the space needs to be owned and held in the wallet that the gallery owner connects. A gallery is better with sound, but you can’t connect Spotify, so you’re incentivized to explore and support NFT-backed music. It gives NFTs a real utility beyond status and patronage. Plus, collectors may be able to host events and shows to earn money on their collections, turning them into income-generating assets.

Importantly, while ownership is decentralized -- you don’t need to hand over your NFTs to Cyber to display them -- discovery is centralized. Cyber’s home page lets visitors explore popular, trending, and new galleries right from the site instead of needing to search for peoples’ wallets to see their collections.

You should go explore Cyber, or even build your own gallery to try it out. A couple to check out include my friend Richard Kim’s gallery, featuring some amazing generative art projects like Ringers, Fidenza, Chromie Squiggles, and The Eternal Pump…

…and on the lighter side, the Banana Feast Gallery is full of CyberKongs praying, selling bananas, and break dancing.

It’s early here, and I expect the experience would be greatly enhanced with VR goggles, but seeing NFTs in their natural environment makes me appreciate their potential to hold value, the importance of owning NFTs you’re proud to look at and display, and the fact that they’re more than jpegs.

Going deeper into the Metaverse, there are three digital worlds that seem promising, but are waiting for the infrastructure to catch up to unlock the full experience: The Sandbox, Somnium Space, and Decentraland. All three are proto-Metaverses that let users own parcels of land as NFTs, build on them, and create experiences for themselves and others. All three have publicly available tokens that double as in-game currency and governance tokens (SAND, CUBE, and MANA, respectively). Each takes a slightly different approach.

Decentraland is the oldest and most open -- there’s no specific use case in mind; landowners can choose what to put on their land, from movie theaters to shops (see: Republic Realm’s Metajuku District) to homes.

The Sandbox is a more gaming-focused world which is also the most open to partnerships with established brands, like this Atari experience:

Somnium Space is explicitly designed for Virtual Reality, and supports body tracking and haptic suits to create the most immersive experience of any of the blockchain-based virtual worlds. This is as close as web3 has come to Ready Player One.

I encourage you to roam Somnium Space, Decentraland, and The Sandbox. You might see both the potential, and the challenges that need to be overcome for these worlds, or something like them, to gain mass adoption. Over the next few years, I suspect a few things will happen for game-like interfaces to become the interface of web3:

Immersive worlds, like Cyber, The Sandbox, Somnium Space, and Decentraland will become richer and easier to navigate.

Non-crypto workplace collaboration companies like Teamflow will make their experiences more immersive, and steal share from Zoom and Slack, making more normal users comfortable with the idea of always-on digital spaces.

Even web3 projects that aren’t themselves virtual worlds will both set up shop inside of these worlds, and incorporate more game-like interfaces on their owned properties. Programming tools like WebGL and threejs, and no-code builders like Typedream, will make websites more immersive and interactive. If you haven’t seen the Yamuchi No. 10 Family Office website, check it out for a glimpse of the future.

Crypto is the in-game currency for the Great Online Game, and for it to break out and reach the mass market of consumers, it will need to build game-like interfaces that celebrate the fun and unique attributes that the underlying technology has to offer.

Physical-Digital Bridges

I’m excited about the Metaverse for all of the normal exciting reasons, and for one more reductive one: for the Metaverse to get sustained mass adoption, it will need to be better than the digital experiences we already have access to. If meeting in the Metaverse is worse than meeting in Zoom, people will just continue to do what they know and meet in Zoom. No one is forcing anyone to use immersive 3D spaces.

But I also don’t think the Metaverse should or will replace physical spaces and interactions. Richer, more immersive web3 interfaces, shouldn’t compete with the time we spend outside, with family and friends, exploring the physical world. Instead, they should compete with the 2D digital experiences in which so many of us spend most of our lives as remote workers and citizens of the internet. I think that in a decade, going back to the way the internet is today will feel a lot like going back to Web 1.0 would feel right now.

Instead of replacing physical experiences, web3 can be a bridge between physical and digital experiences, and give the physical world the same incentives toolkit the digital world currently has access to. NFTs might serve as a scrapbook of the experiences you’ve had -- concerts and games you went to, marathons you ran -- and create a more complete view of yourself than currently exists in your MetaMask. NFT collectors and degens can also be rock climbers and violinists. Rewards programs might be replaced by social tokens that are good for more than just a free coffee on your 13th cup. Your web3 experience will benefit from the worlds you frequent knowing as much about you, on-chain, as you’re willing to share.

I’m not worried about a dystopian future because when you control your wallet and your time, you can choose which information to share, with whom, and which worlds you want to enter. It’s on the app and interface creators to build worlds and experiences that are worth your time.

Into the Future

Let me wrap up with a big and obvious caveat: I am not a designer, or an engineer, or even that smart. Over the next few years, far more creative and talented people are going to come up with ideas that blow everything I wrote out of the water, and other people are going to come in and build even wilder experiences on top of those ideas. That’s the beauty of composability and compounding. Based on conversations with builders way smarter than me and explorations of new interfaces that have been built so far, this is a snapshot of my best guess as to how this will play out.

Throughout the history of the internet, new interfaces have unleashed waves of consumer demand. New technologies can’t live up to their full potential when confined by old interfaces. That’s not to say that every web3 website will look like a video game or incorporate 3D design -- there are plenty of websites on the internet today that aren’t centered around user-generated content and real-time interaction. But I do believe that there’s so much complexity under the surface in crypto, and so many characteristics baked in, that 3D, game-like environments are the right level of abstraction for the average user to make sense of it all.

First, we shape our interfaces; thereafter, they shape us.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

See you on Monday!

Thanks for reading!

Packy

Great stuff as usual, Packy. Thank you for helping us all see the future a little bit sooner.

One maybe helpful analogy for the middle part of your explanations above is the "single sign on" revolution that happened about a dozen years ago. Google and FB offering their credential authorization tools as integrations to sites across the web consolidated and improved many user experiences (and also increased user tracking). Sounds similar to your description of what Meta Mask, Station, Crucible and other wallet/profile tools are trying to do now.

I wish more writers of this sort of substance would take the time you did to explore and compose so well. I am exceptionally awed with your vision and knowledge.<a href="https://allgclub.com/register/" rel=dofollow >สมัครจีคลับโดยตรง</a>