Welcome to the 551 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 29,828 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by…

ExitUp is a weekly newsletter that delivers a curated list of fresh job openings across PE, VC, strategy/biz ops, finance, marketing, and product management right to your inbox. You'll also get useful insights to help you navigate your job search so that when the time comes, you'll be ready to nail the interview.

Just this week, ExitUp featured dream jobs at WorkLife Ventures, Twitter, Niantic, Impossible Foods, and more. Go put what you read about in Not Boring to work.

Subscribe for free today, and find your exit opportunity with ExitUp.

BABA Black Sheep

We Don’t Know (Where) Jack (Is)

I can’t stop buying Chinese tech conglomerates.

After writing about Tencent in August (here and here), I’ve slowly built it into my second largest holding. Every time it drops on news that the US or Chinese government said or did something, I buy.

Now, its main rival, Alibaba, is embroiled in a situation so wild that if it happened in the US, to Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk, it’s all we’d be talking about. Its stock is down 25% from October highs. My mouth is starting to water.

In case you missed it, here’s what went down:

On October 24th, days away from the IPO of his fintech giant Ant Group, Alibaba founder and ex-CEO and Chairman, Jack Ma told an audience of China’s financitariat:

Banks today still hold a pawnshop mentality…. It is impossible for the pawnshop mentality to support the financial demand of global development over the next 30 years. We must leverage our technological capabilities today and build a credit system based on big data, to get rid of the pawnshop mentality.

We can’t use yesterday’s methods to regulate the future.

To western ears, those sound like the boastful and ultimately harmless words of a passionate entrepreneur. But in China, where the Chinese Communist Party (“CCP”) has long run the banking system and doesn’t take kindly to challenges, those were fighting words. And in China, the CCP doesn’t lose fights.

Jack’s remarks set off a chain of events that derailed Ant Group’s planned November 5th $37 billion IPO, which would have valued the Alibaba spin-off, of which the company still owns 33%, north of $300 billion.

November 2nd: China’s central bank and securities regulators called Jack and two Ant Group executives to a meeting.

On the same day, regulators announced that they were considering regulating Ant’s lending arm, its main growth engine, more like a bank and less like a tech company.

November 3rd: the Shanghai and Hong Kong Stock Exchanges suspended the offerings at President Xi Jinping’s command.

December 23rd: Chinese regulators opened an antitrust probe into whether Alibaba had engaged in monopolistic practices. Alibaba’s stock (BABA) tumbled 13%.

December 27th: Regulators told Ant to return to its payments roots and come up with a plan to pare down its lending, insurance, and wealth management business.

And as of today, 79 days after that explosive speech, no one has seen China’s third-richest man in public. Jack Ma is missing.

Rumors have flown around the internet in recent days as to Jack’s whereabouts. For a minute, people feared he might be in jail or dead. Then sources close to Jack said he was just “laying low.” A video of a Jack doppelganger went viral, saying that he’d been found repairing an AC unit:

Pardon my Mandarin, but this is fucking crazy. The founder and CEO of the world’s largest eCommerce business by Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) and one of China’s Big Three just… disappeared.

In China, Alibaba is like Amazon, Google, DoorDash, YouTube, Slack, Square, and Farfetch all rolled into one, plus some. Most people in the west still know Alibaba for its original and eponymous Alibaba.com, the B2B marketplace where wholesalers can find 1,000 ballpoint pens for $0.10 each. Chances are, when you buy something on Amazon, that product started on Alibaba, which has quietly powered the drop-shipping and third-party seller economy by letting anyone buy from foreign manufacturers and ship to the world.

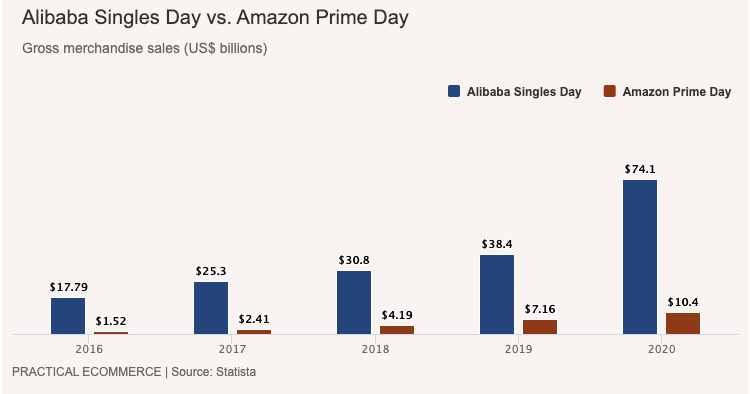

But the legacy business makes up less than 5% of the company’s total revenue today. Its main sites, domestic B2C marketplaces Taobao and Tmall, are so massive that on 2020’s Singles’ Day, China’s version Black Friday/Cyber Monday, it did 7x the GMV that Amazon did on Prime Day. If a western brand wants to sell to China’s 1 billion+ consumers, it needs to go through Tmall.

Like Tencent, Alibaba has its hand in everything, often because if foreign businesses want to do business in China, they need to go through one of its two biggest companies. In recent years, Alibaba has expanded beyond eCommerce. It owns, among other things:

Youku: the Chinese version of YouTube and Hulu rolled into one.

Alibaba Pictures: a film production studio and investor that financed two Mission: Impossible movies, Fallout and Rogue Nation.

Startup Investments: Alibaba still owns 2.3% of Lyft, and even invested in Quibi 🙈

DingTalk: The Chinese equivalent of Slack.

Cainiao: a logistics platform with ambitions to sit at the center of the world’s logistics.

Ant Group: a 33% stake in China’s biggest fintech company.

Jack Ma and Alibaba have arguably done more than any single company to grow the Chinese middle class and improve the quality of life for the average Chinese person. But since Jack (characteristically) opened his mouth in October, Alibaba is a black sheep.

Look, I have no idea where Jack is or when he might come back. I have no idea what the government is going to do with Ant Group or whether it is going to break up Alibaba. But it doesn’t seem like anyone else does, either. As a result, this is what BABA’s stock chart looks like since October 24th.

After trading in line with other Chinese internet stocks throughout the year, BABA tanked in November after the government pulled the Ant IPO. It kept dropping as the government announced an antitrust probe, as the US signaled it might include Alibaba on a list of banned companies, and, of course, as people realized Ma went MiA.

BABA is down 25.5% from its October 27th high of $317. It’s lost $219 billion, or an entire Pinduoduo, in market cap. In a matter of months, it’s become the tech megacap equivalent of a deep value stock.

As it stands, the world’s tenth largest company by market cap is either mouthwateringly cheap or wildly risky. I don’t know which it is -- prognosticating on the actions of the CCP is above my pay grade -- and nor does anyone else. But it’s going to create an opportunity either way, and we need to be prepared. So today, we’re going to learn about Alibaba.

The Story of Magic Jack and Alibaba

The Strategic Tao of Jack

What is Alibaba Today?

Alibaba vs. Amazon

Ant IPO Debacle.

Investing in China

What to Do About BABA

When I wrote about Tencent in August, I wrote that “Tencent is the most important company that many Americans know the least about.” Alibaba’s story is more well-known, partially for the same reason that the company is in trouble right now: unlike Tencent’s Pony Ma, Jack Ma speaks English, and he’s never been shy to wield his words.

The Story of Magic Jack and Alibaba

Note: I’ve used Porter Erisman’s documentary Crocodile in the Yangtze, Duncan Clark’s book Alibaba: The House That Jack Ma Built, and the Acquired podcast on Alibaba to piece together Alibaba’s history.

Jack Ma and Alibaba created eCommerce in China, the largest market in the world, from nothing, against all odds. He succeeded through surprisingly good luck, a tireless work ethic, and what author Duncan Clark called “a unique Chinese combination of blarney and chutzpah... ‘Jack Magic.’”

Jack Ma was born Ma Yun in Hangzhou, China in 1964, just two years before Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution was a movement to “preserve Chinese Communism by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society.” That seems like bad timing for a future entrepreneur to be born. But two things happened early in Jack’s life that set him down the path towards international business.

First, when Jack was eight, Richard Nixon visited China in an effort to open the Communist country up to the world. On the trip, Nixon visited Jack’s home city with camera crews in tow, showing off its beauty and attracting western tourists to what was then a Tier 2 city.

Jack fell in love with English. Every day, for nine years, he biked to the hotel at which Nixon had stayed, the Shangri-La Hotel Hangzhou, to chat up tourists and offer them tours of the city in order to better learn the language.

It worked. While he was so bad at math that he failed the college entrance exams twice, he finally passed on the third try with scores good enough to get into the mediocre Hangzhou Teachers College. Upon graduating, and after famously being the only person of twenty-four applicants not hired to work at a new KFC in town, he secured a job as an English teacher making $12 per hour.

Second, in 1978, when Jack was fourteen, President Deng Xiaoping brought about a series of market-based economic reforms in China that not only legalized, but encouraged, entrepreneurship. Recall that Pony Ma also benefited from Xiaoping’s policies: he grew up in Shenzhen, a special economic zone established as part of the new “reform and opening policy.”

Those two things combined to put Jack in a surprisingly fortuitous position: an entrepreneurially-minded English speaker coming of age at a time when China began encouraging entrepreneurship and opened up to the west.

Jack took advantage of his good fortune, but it took him a little while to find his footing in business. In 1994, fulfilling a promise to himself to start a company before turning 30, Jack started the Hangzhou Hope Translation Agency. The Agency was only moderately successful, but through it, nearby Tonglu County found Jack and enlisted him to go to the States to resolve a highway deal gone bad.

There are various accounts of what happened in America, and it’s one of very few subjects about which Jack isn’t willing to talk, but the gist is this:

The American business partner turned out to be a con man, and he held Jack hostage, either in a mansion in Malibu or a penthouse in Las Vegas, to keep him quiet.

Somehow, Jack escaped.

He made it to Seattle, where he stayed with a friend who worked at an internet company.

That friend showed Jack the internet for the first time.

Jack looked up “beer,” and found American beer, and German beer, but no Chinese beer… no Chinese anything for that matter.

Jack asked his friend to set up a website for the Hope Translation Agency.

Within two hours, he got five inbound requests: three from the US, one from China, and one from Japan.

He was hooked on the internet, and went home resolved to start an internet business.

When Jack got back to Hangzhou, he set up China Pages, which built and listed sites for Chinese businesses. Thanks to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, the site has been preserved for posterity:

ChinaPages caught the attention of a state-sponsored communications company, which threatened to “compete” it out of business, and then bought a controlling stake for $140k. Jack lost control, left, and took a job working for the government.

While the government job was painfully slow and boring for a restless entrepreneur like Jack, two things happened there that played a role in Alibaba’s development and trajectory:

ChinaMarket. Jack and a team he recruited from ChinaPages built ChinaMarket.com.cn, a government run B2B message board which let users post supply or demand requests and enter into “confidential business negotiations in encrypted Business ChatRooms.”

Jerry Yang. When Yahoo! founder Jerry Yang came to China in late 1997, the government needed someone who worked for the government, understood the internet, and spoke English to tour him around. Jack Ma was the perfect fit.

ChinaMarket was dragged down by bureaucracy -- each submission had to go through layers of government approval -- but it gave Jack the seed of an idea. He quit and left Beijing for Hangzhou. In early 1999, just as the internet bubble was picking up steam, Jack and seventeen co-founders (!!) created Alibaba.com. Alibaba, so named because it would “Open Sesame” China to foreign buyers, built a site that allowed small Chinese manufacturers to tell buyers around the world that they were open for business.

That February, he called a meeting in his Lakeside Gardens apartment with the full team. Ever-confident, he had the meeting filmed, giving us a glimpse into Jack’s prescience and early leadership:

In May, Jack met Joe Tsai (if you’re an NBA fan, that name should sound familiar: he owns the Brooklyn Nets), and convinced him (and his wife) to leave his $700k per year private equity job in Hong Kong to come join his ragtag crew in Hangzhou. Joe immediately got to work trying to raise money for the business.

He set Alibaba up as a Variable Interest Entity in the Cayman Islands, which would allow it to take money from foreign investors, and organized a trip for the two to Silicon Valley. The trip was unsuccessful, but right around that time, China.com IPO’d at a $1 billion valuation, and the China rush was on.

When they got home, Joe called up an old friend, Shirley Lin, who was leading Goldman’s tech investments in Asia. They negotiated a deal for Goldman to acquire a majority stake in Alibaba for $5 million. Jack pushed back at a 50/50 split, and Lin agreed, but the Goldman investment committee decided it didn’t want all that risk 🤦🏻♂️. Goldman kept 33% and syndicated out 17% to GGV, Venture TDF, Fidelity Growth Partners, Investor AB (Joe’s old employer), and Transpac.

(Goldman would sell its stake in 2004, after Lin left the company, for $22 million. The 6x return isn’t bad, until you calculate that 33% of Alibaba is worth $210 billion today! 🤦🏻♂️ The lesson: never sell!)

Money in the bank, Alibaba got back to building, signing up more than forty thousand users by the end of the year largely by keeping the site free. At the time, the site was little more than a directory and message board, as captured by the Wayback Machine:

The fight for talent in a hot China tech market was fierce, but Alibaba had an advantage: Hangzhou. Being in a Tier 2 city gave Alibaba access to cheap talent with few other options and cheap real estate (they signed a 200k sf office lease for $80k per year, or $0.40/sf, in 2000). In a bit of foreshadowing, Jack highlighted another benefit:

Even though the infrastructure is not as good as in Shanghai, it’s better to be as far away from the central government as possible.

Money became even less of an issue for Alibaba just a couple of months later, when, in January 2000, SoftBank led a $20 million investment for 30% of Alibaba. As I wrote in Masa Madness, Masayoshi Son led the deal himself after listening to Jack speak for just five minutes. At the time, Jack said, “We didn't talk about revenues; we didn't even talk about a business model. We just talked about a shared vision. Both of us make quick decisions.”

Reflecting back at Alibaba’s 2014 IPO, the notoriously eccentric Son said, “It was the look in his eye, it was an ‘animal smell.’ … I invested based on my sense of smell.” His nose was on point: when Alibaba IPO’d, the investment was worth $60 billion, a 3,000x return. That investment is responsible for SoftBank’s Vision Fund, fwiw.

The cash came in just as the dot com bubble was about to burst, and allowed Alibaba to keep building. It surpassed 300,000 members in the summer of 2000. In July, Forbes made Jack the first Chinese business person on the cover in fifty years, and in August, The Economist profiled Jack in a piece called The Jack Who Would Be King.

Despite member growth and press, though, Alibaba wasn’t making any money. It was becoming bloated, with engineering offices in Silicon Valley. So Jack brought in a former GE exec, Savio Kwan, who killed the US office and figured out how to start making money.

Since the Chinese market was so nascent, the Alibaba team realized it couldn’t just copy the US business model of charging businesses to list and taking a cut of transactions. Instead, Alibaba gave away the product and transactions for free and charged sellers for better placement. It worked.

For the first time, in early 2002, Alibaba turned a profit. From Crocodile in the Yangtze:

The company was PUMPED:

Just when things were looking up, though, Alibaba would face two of its biggest challenges yet.

The Strategic Tao of Jack

During a global pandemic due to a respiratory illness that originated in China, Alibaba faced a crisis that put the future of the company in jeopardy. No, no, not COVID. SARS.

In May 2003, an Alibaba employee named Kitty Song contracted SARS, forcing the company into a two-week quarantine, during which 400 employees brought computers home to keep the company running. While it was scary and challenging in the short-term, SARS actually helped Alibaba grow. Does this paragraph from Alibaba: The House That Jack Built sound familiar?

Although it sickened thousands and killed almost eight hundred people, the outbreak had a curiously beneficial impact on the Chinese Internet sector, including Alibaba. SARS validated digital mobile telephony and the Internet, and so came to represent the turning point when the Internet emerged as a truly mass medium in China.

Around the same time, eBay, the darling of the American internet, came to China, dealing Jack his strongest competitor yet. The four year battle is worth diving into, because it sheds light on how Alibaba thinks about growing and capturing share in nascent, competitive markets, and is a lesson in Counter-Positioning, customer centricity, and Jack Ma’s unique brand of strategic Tao. It’s also one of the greatest business stories in recent history.

It’s hard to remember this now, but once upon a time, eBay was one of the most powerful companies on the internet. After going public in 1998, at a $2 billion valuation, the company rode the dot com bubble to a $30 billion valuation in March 2000.

That attracted copycats in China, the most promising of which was called EachNet. Founded by HBS grad Shao Yibo (“Bo”), EachNet raised $20.5 million in October 2000 after the crash. In the fall of 2001, eBay CEO Meg Whitman came to China to meet with Bo, and in March 2002, the companies announced that eBay was buying a 33% stake in EachNet for $30 million.

While Alibaba’s B2B business and eBay and EachNet’s B2C businesses don’t seem directly competitive on paper, Jack realized that, “In China, there are so many small businesses that people don’t make a clear distinction between business and consumer.”

To prepare for battle, Jack raised a fresh $80 million from SoftBank. Then, during the SARS lockdown, a seven-person team from Alibaba headed to the Lakeside Gardens apartment to work on a top-secret skunkworks project. They worked around the clock to create Taobao, which means “treasure hunt,” Alibaba’s C2C marketplace.

In May 2003, they quietly launched the site, and it picked up so much early traction that Alibaba employees, unaware of the project, emailed Jack to alert him that there was a new competitor in town. In June, the real competitor, eBay, announced that it was acquiring the rest of EachNet for $150 million. eBay, under pressure from shareholders to grow, needed China. CEO Meg Whitman, also an HBS grad, said, "Share of e-commerce in China is likely to be the defining measure of success on the net."

Then, on July 10th, Jack decided it was time to launch Taobao publicly. The company held an event announcing that they were behind Taobao, and employees were ecstatic. Jack announced that Taobao was a consumer marketplace customized for China, and that it would be completely free for three years. Alibaba, via Taobao, was going to war with eBay.

The odds were stacked against Alibaba, but Jack put on a masterclass in guerilla warfare, focusing on three things: Counter-Positioning, customer centricity, and his own special strategic Tao. In doing so, Jack proved that he’s one of the greatest Worldbuilders in business history.

Customer Centricity

“We’re a customer-first company” is such a cliche and common phrase among startups at this point that it’s become meaningless. But customers are truly at the heart of Alibaba, explicitly above employees and investors in its company values.

That checks out in the decisions the company has made. Specifically in the fight against eBay, it was Jack’s understanding of the similarities between small business customers and consumers that made him realize that Alibaba needed Taobao to compete directly with eBay.

Additionally, understanding that customers needed a way to pay for things online in order to build trust and remove friction from an otherwise uncertain process, the team built an escrow service, AliPay, that would become a multi-hundred-billion dollar giant that we will return to later.

And that customer awareness also led Jack to decide to keep the product free for three years, because he knew that he couldn’t both convince customers to try something new and charge them at the same time, investors be damned.

Counter-Positioning

The decision not to charge for Taobao for three years is a brilliant example of counter-positioning. My favorite of the 7 Powers, counter-positioning is “the practice of developing your business model such that incumbents have conflicting incentives preventing them to compete effectively.”

Jack realized that eBay was under intense pressure from shareholders to start making money in China, and that although free was the right model and eBay had deeper pockets, it would not be able to follow Alibaba’s lead. At the launch event, he announced that Taobao would be free for three years, and he was right: instead of eliminating its fees, eBay vocally defended its paid model, which sowed the seeds of its eventual defeat.

Strategic Tao of Jack

Competition is the greatest joy. When you compete with others, and find that it brings you more and more agony, there must be something wrong with your competition strategy.

-- Jack Ma

Jack Ma grew up reading martial arts novels and studying Mao, so when eBay came to his doorstep looking for war, he knew what to do. Alibaba would have to pull eBay into guerilla warfare. According to Crocodile in the Yangtze, directed by a former Alibaba exec, the company’s battle plan went something like this:

Declare war on eBay to get free press and piggyback off the larger company’s ad budget

Don’t make personal attacks on Meg Whitman or play the nationalism card

Do argue that eBay’s business model didn’t fit in the Chinese market

Take the battle to eBay’s turf by organizing a US press tour, turning up the heat on the bigger, public company

Stay locally focused: Taobao built a cute product with animated characters to appeal to younger Chinese shoppers who would fuel its growth, while eBay tried to fit its China site into the same architecture and brand that it used globally.

After three years of battle, while eBay was outwardly confident about China, inwardly, it gave up. In 2005, Meg Whitman called Jack in to discuss investing in Alibaba. He turned her down: she didn’t actually want to grow the market or help small businesses, she just wanted to capture as much of the existing market as she could.

Instead, Jack turned to the man he had once guided around the Great Wall: Jerry Yang. Yahoo! invested $1 billion for 40% of Yahoo! in one of the greatest investments of all time.

With cash in the bank, Alibaba pledged to keep Taobao free for three more years. Almost immediately, eBay responded by saying to the press, “Free is not a business model.” Jack, as captured in the documentary, was giddy that his foe responded so quickly. He told the camera:

Business is fun. Competition is fun. Don’t take it too seriously. They took it too seriously in China. eBay’s days are numbered. If we have no enemy in our hearts, we will be invincible. The most important thing is about increasing our transaction volume and user base.

He was right. In 2006, eBay announced that it was retreating from the Chinese market.

Jack Ma: Worldbuilder

Jack Ma was a Worldbuilder, that rare and special leader who is able to see a non-obvious future and will it into being. Specifically, Jack:

Predicted that internet commerce in China was going to be orders of magnitude larger than it was in 2003, and that it didn’t matter who was leading then, but who would be leading in ten years.

Used a free offering and payment product to build up both sides of the network, growing the market before worrying about monetizing it.

Timestamped the whole thing on camera, laying out a vision that has largely come true over the next seventeen years.

As Alibaba faces its next seventeen years of challenges, including growing and leading the nascent cloud and logistics markets, the same strategies Alibaba used to win eCommerce will once again prove useful.

Jack Ma stepped down as CEO of Alibaba in 2013, and retired from the Chairman role in late 2020, but the company is still infused with the culture he built and the strategic focus he put in place.

What is Alibaba Today?

In 2007, fresh off its victory over eBay, Alibaba.com went public, raising $1.5 billion. In a rare move, Alibaba Group, the parent company that also owned the fast-growing-but-unprofitable Taobao and the promising payments platform AliPay, stayed private. Then, in 2014, Alibaba Group brought Alibaba.com private and took the whole thing public on the NYSE, raising $25 billion in the largest IPO of all time.

Since going public at $68 (the first trade actually priced at $92), BABA grew 4.7x to its October 27th peak. Since regulators took a special interest in Ant and Alibaba in late October, the stock has fallen 25% while Chinese internet ETF KWEB rose 14%.

The question is: when the dust settles, is Alibaba’s value closer to the its 2014 IPO-day close of $240 billion or its recent high of $858 billion? It’s a big, meaty question, so let’s break it down by looking at the businesses that make up Alibaba to back into the uncertainty discount.

Alibaba’s Businesses

The easiest way to think about Alibaba, and certainly the most common analogy, is like a Chinese Amazon. Like Amazon, its main revenue drivers are ecommerce and cloud. While the comparison is easy, from a business model perspective, it also happens to be wrong.

First things first, while Amazon is an asset-heavy business, taking inventory and managing logistics, Alibaba operates asset-light marketplaces, and monetizes mainly via “Customer Management Services,” or tools, ads, and better placement.

Second, while Amazon has long run eCommerce at thin margins and generated high margins from AWS, Alibaba runs eCommerce at high margins (35% in the most recent quarter) and loses money on Alibaba Cloud (-1% in the most recent quarter). Should that change, as the company predicts it will this fiscal year, that’s a big opportunity for BABA’s bottom line.

Finally, Alibaba, through its seemingly sprawling roster of companies, is building the most complete possible data set on its customers: what they buy, who their friends are, where they travel, and more. Lillian Li breaks down the strategy nicely here:

To better understand what BABA is building let’s look at the business lines. In the quarter ended September 2020:

67% of Alibaba’s revenue came from retail commerce (Taobao, Tmall, AliExpress, Lazada, and a host of smaller properties)

10% came from Alibaba Cloud, the company’s answer to AWS.

Alibaba, the original wholesale business, made up just 4% of revenue.

The remaining 19% of revenue came from logistics (5%), local consumer services (6%), digital media & entertainment (5%), innovation initiatives & others (3%).

While I’ve always associated Alibaba with the B2C wholesale platform, retail commerce drives the business.

Retail Commerce

More people shop on Alibaba’s properties than any other platform in the world. Over 1 billion people shopped on Alibaba’s sites in FY2020.

Alibaba’s retail commerce platforms fall into two categories: China and international.

International retail commerce is relatively simple, so let’s do that first. It’s all about Lazada and AliExpress.

Alibaba owns a majority stake in Lazada, a leading eCommerce brand in Southeast Asia, having plowed more than $4 billion into the company starting in 2016. Ironically, given its experience fighting eBay on its home turf, Alibaba has struggled to grow Lazada as fast as it grows its China properties, and has resorted to shaking up management and sending in Alibaba execs to try to right the ship. Tencent-backed Sea Limited’s Shopee is beating Lazada in important markets like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

AliExpress, on which international shoppers can buy retail from China at ridiculously low prices, is wild. It’s like shopping in a local market, online, with all of the randomness that entails. In just one random screenshot I took, I spy a knock-off theragun, custom photo prints, $3.43 “Classic Romantic Shiny Full White” jewelry, and a whole lot of tablecloths. AliExpress can take weeks to deliver, and may or may not ever arrive, but you can’t beat the prices!

AliExpress and Lazada made up just 5% of revenue, or $1.2 billion, in Q2 2021, and is growing in line with the overall business at 30%. The real cash cow for Alibaba is China Commerce Retail.

In China, in addition to a host of smaller, more targeted retail sites, the two main platforms, with 742 million active customers, are Taobao and Tmall:

Taobao, launched in 2003, is Alibaba’s domestic B2C and C2C platform, catering to individuals and small merchants as sellers. In line with Alibaba’s small business-friendly ethos, Taobao still doesn’t charge transaction fees, and instead monetizes through ads and other services designed to help them boost sales.

Tmall, launched in 2008, is a B2C platform focused on selling domestic and international brands to China’s growing middle class. If foreign brands want to reach Chinese consumers, they have to go through Tmall. As a result, Tmall monetizes by charging merchants a deposit, an annual fee, and commission fees on each transaction.

Fun fact: in 2009, Jack seized on the Chinese Singles’ Day holiday by offering “Double 11” deals on Tmall, and drove $340 million on the site. From its origins on Tmall, Singles’ Day has grown into the most important day for eCommerce in the world, with Alibaba’s properties driving $74 billion in GMV in 2020 through virtual events.

While there’s a perception that Chinese customers spend less, the company reported that 190 million people spent over $1,000 through Alibaba in FY2020. For comparison, Amazon has 126 million Prime Members at last count, and Prime members spend $1,400 per year on average. Alibaba has its own membership program, 88VIP, and members spend 9x as much as the average Alibaba retail customer.

Alibaba’s model is different than traditional eCommerce models in the United States (although by offering advertising, logistics, and a third-party marketplace, Amazon is getting closer). Despite not charging transaction fees on Taobao, Alibaba is able to take a huge cut of the revenue generated on its platforms by offering all of the services that a merchant might need to run their business. As the company lays out in its most recent investor presentation, Alibaba’s subsidiaries offer inventory & logistics, distribution, marketing, R&D and IT, financing, and other operating services to merchants. They can run nearly the entire small business P&L.

By the time merchants are done paying Alibaba to handle everything besides manufacturing for them, they’re left with $4 in profits for every $100 in revenue. That’s an incredibly powerful model. Not only does Alibaba take $96 of every $100 dollars, they build in incredibly high switching costs. Why sell somewhere else when Alibaba handles every single piece of your business for you?

Acquired’s David Rosenthal described Alibaba’s business model as, “Amazon with the capital intensity aspects of Google.” The model is working. In Q2 2021, it generated $14.7 billion in revenue, 62% of Alibaba’s total, and Core Commerce as a whole was Alibaba’s most profitable segment at 35% Adjusted EBITDA Margins.

Wholesale Commerce

Alibaba’s original business, B2B wholesale commerce, is just a small piece of what it does today, generating $1.1 billion in Q2 2021 revenue, 4% of Alibaba’s total. Half of that revenue comes from China (1688.com), and half comes from abroad (Alibaba.com).

Simply, Alibaba connects manufacturers with wholesale buyers. Let’s say I wanted to start selling custom Not Boring notebooks. There’s a lot of content here, and maybe you want to take some notes. Before Alibaba, I would have had to find the number for a manufacturer, call them up, and negotiate prices, often across language barriers. Today, I can go to Alibaba.com, search for “customizable notebooks,” and find thousands of options from manufacturers in nine countries.

I need to fill a minimum order size -- 1,000 notebooks for the top sponsored result -- and can get discounts if I buy more. Then, all that’s left for me is to receive the order, set up an online storefront, and start selling. Fascinatingly, while competitors on paper, Alibaba actually powers much of Amazon’s third-party business via its wholesaling.

On the most recent episode of Founder’s Field Guide, Thrasio CEO Carlos Cashman told Patrick O’Shaughnessy:

Alibaba likely powers a large percentage of Amazon’s third-party marketplace, but like Taobao, though, it doesn’t charge transaction fees, and makes money by selling better exposure or unlimited product listings to merchants.

In FY2020, Alibaba did over $3 billion in wholesale commerce revenue, and it’s on pace to do more than $4 billion in FY2021 as eCommerce grows around the world, quietly powered by Alibaba.

Alibaba Cloud

Alibaba launched its second biggest and second fastest-growing business line, Alibaba Cloud, in 2009. It was the company’s first attempt to extend its mission, “To make it easy to do business anywhere,” beyond eCommerce. It was only natural. Jack Ma’s Chinese name literally means Cloud Horse.

Like Amazon, Alibaba first used its cloud product internally, to support its own properties. In November 2010, it handled 2.4 billion pageviews in one day on Taobao’s first Singles’ Day.

Today, Alibaba is the fifth largest cloud provider in the world, and far and away the largest cloud provider in China. It has over 3x the market share of Tencent, the next closest competitor.

Alibaba seems to be running the same strategy that it ran for its eCommerce businesses. In a nascent and rapidly growing market, getting and staying out front means more than turning a profit. Eleven years into Cloud, Alibaba is still losing money. In Q2, it lost $23 million on $2.2 billion in revenue, but that revenue grew 60% year over and the company expects to turn a profit this year.

In a 2018 interview, Alibaba CEO Daniel Zhang told CNBC that cloud computing would become Alibaba’s main business in the future. He reiterated that sentiment in September, saying that cloud “is the kind of opportunity that only comes once in a generation,” and that the world is in “a nascent stage of the global cloud era.”

With that kind of opportunity ahead of it, it’s not surprising that the company has focused its efforts thus far on market share. Turning on the profit engines from the leading position should serve BABA well for years to come.

Logistics

Unlike Amazon, Alibaba doesn’t operate its own logistics network. Instead, it co-founded a platform, Cainiao, in 2013. The subsidiary is, “an open platform that allows for collaboration with 3,000 logistics partners and 3 million couriers—including the top 15 delivery firms inside China and 100 operating internationally.” It currently allows shippers to send a 1kg package anywhere in China in 24 hours for 30 cents, and makes these cute automated delivery vehicles.

Today, Cainiao is more important strategically than financially. While anyone can use Cainiao to deliver packages, the process is faster, easier, and more seamless for those who sell on an Alibaba eCommerce platform and take payment via AliPay, strengthening Alibaba’s switching costs. It generated $1.2 billion in Q2 2021 but lost money. In the future, Alibaba expects Cainiao to become the operating system for global logistics, and a profit center for the company.

Consumer Services, Media & Entertainment, and Innovation

In the near-term, the success of the eCommerce and cloud businesses will determine Alibaba’s success. But while Cloud is growing and improving its margins, eCommerce is growing more slowly, and margins are compressing ever so slightly as the company faces more competition from Tencent-backed JD.com and new entrants like Pinduoduo.

To fulfill Jack’s 102-year vision of making it easy to do business anywhere, the company is investing its significant cash pile ($63 billion as of last quarter) into new lines of business. Specifically, it’s building or acquiring startups under three categories: Local Consumer Services, Digital Media & Entertainment, and Innovation Initiatives. Innovation initiatives, including Maps, smart speaker Tmall Genie, AliOS, and DingTalk make up just 1% of revenue combined, but Local Consumer Services and Digital Media & Entertainment make up a growing piece of Alibaba’s future plans. Let’s take a look at one business in each.

Local Consumer Services: ele.me

In 2018, Alibaba acquired local delivery startup ele.me for $9.5 billion. You can think of it like DoorDash for China: the company started out by offering a food delivery platform, but is quickly adding capabilities in Online-to-Offline (O2O), or “new retail.” The company competes directly with Meituan-Dianping, the market leader. Meituan is the undisputed leader in food delivery, but China Tech Blog points out that there’s a new battle underway in O2O that is anyone’s game.

The prize here is massive: Meituan currently has a $234 billion market cap, and Tencent’s 20.1% stake in the business is currently its most valuable holding among a portfolio of phenomenal investments. Local consumer services is a proxy war for the two giants, with Tencent pushing Meituan through WeChat, and Alibaba pushing ele.me through AliPay. While Meituan’s lead seems insurmountable, O2O seems to better play into Alibaba’s retail commerce strength than food does.

Alibaba did $1.4 billion in local consumer services revenue, led by ele.me, in Q2 2021, representing 6% of the company’s business.

Digital Media & Entertainment: Youku

In 2016, Alibaba bought streaming video platform Youku for $5.4 billion. The platform, often referred to as the “YouTube of China,” is the third most popular video streaming site in the country, after Tencent Video and Baidu’s iQiyi, according to Pandaily. It also faces competition for screentime from ByteDance and Bilibili, which sport $140 billion and $41 billion valuations, respectively.

Youku is part of Alibaba’s growing digital media portfolio, which includes Alibaba Pictures (which backed two Mission: Impossible), Tmall TV, ticketing platform Damai, and Alibaba Music. In Q2 2021, this segment lost $105 million on revenues of $1.2 billion. As shopping moves more interactive and video-based, Alibaba will need to keep investing in this area and figure it out if it’s going to compete with the next generation of eCommerce startups.

Investments

On top of all of its own business lines, Alibaba also makes investments in startups and public companies around the world.

In Reliance’s Next Act, for example, I wrote that the company is one of the leading investors in Indian unicorns. Given India and China’s soured relations, and the company’s own failures, India is closed to the company for now.

In the public markets, Alibaba owns a 2.3% stake in Lyft, and recently made post-IPO investments in luxury fashion platform Farfetch and Chinese Twitch, Bilibili.

While Alibaba’s portfolio is over 200 companies strong, it’s not as impressive or important to the business’ future as Tencent’s. That said, there is likely upside surprise waiting in Alibaba’s portfolio of eCommerce and China investments, two categories that performed particularly well in 2020.

With all of Alibaba’s businesses a little more clear, it’s time to turn back to Amazon, and that uncertainty discount.

Alibaba vs. Amazon

I just said that from a business model perspective, it’s wrong to compare Alibaba to Amazon. But it’s still the most useful comp we have for BABA. So how does Alibaba compare to Amazon?

It’s hard to compare the two companies apples-to-apples from a revenue perspective because the business models are so different, but let’s take a deeper look.

Alibaba does nearly 3x the GMV that Amazon does and generated nearly twice the profit in FY2020.

While Alibaba grew revenue faster from FY2019 to FY2020, Amazon grew faster YoY in the most recent quarter, at 37% compared to 30% for BABA.

Alibaba grew net income more than twice as fast as its American counterpart in FY2020.

Both have nearly exactly the same amount of cash on their balance sheets: Amazon had $68 billion as of last quarter, and Alibaba had $63 billion.

And while AWS is a big profit driver for Amazon, Alibaba is doing what Alibaba (and Amazon) has always done: playing the long game and losing money upfront to grow the market and capture profits down the line.

Back to that Alibaba discount: how much less are investors paying for Alibaba than Amazon because of the hair on the company?

This week, we’ll get a chance to see how the credit markets feel about Alibaba given everything that’s gone on when the company raises $5-8 billion in debt. A successful raise in the credit markets might help restore confidence in the equity markets, but for now, the equity markets seem shook.

Looking at the two companies’ P/E ratios is an imprecise way to measure the discount, particularly since Amazon famously forgoes profits today for profits tomorrow. But then again, so does Alibaba, so let’s go with it.

AMZN trades at 3.7x the P/E of BABA today. As of BABA’s peak pre-crash on October 27th, AMZN was trading at 2.8x the P/E of BABA.

In other words, BABA traded at a 65% discount to AMZN pre-crackdown, and trades at a 73% discount today, and it arguably has a better business model, more complete customer data, and more growth prospects than Bezos and crew.

And that’s not even taking into account Alibaba’s 33% stake in Ant Group.

Ant IPO Debacle

As of late October, Alibaba’s 33% stake in Ant Group was on the verge of becoming worth more than $100 billion dollars in the public markets. The business that started as AliPay in 2003 was set to go public in a $37 billion IPO, surpassing Alibaba’s record as the largest ever, when Jack Ma opened his mouth and pissed off the wrong banking regulators.

In November, the Shanghai and Hong Kong Exchanges canceled the IPO. Regulators threatened making Ant behave more like a bank, which would mean taking on more risk, capping consumer lending, and threatening its tech multiples. In December, they told Ant to focus on its core payments business.

The question is: after all of that, what is Alibaba’s 33% stake in Ant worth now?

In its seventeen years, AliPay has grown from a simple escrow service that helped people buy things on Taobao into Ant Group, a financial behemoth unlike any the world has ever seen. This graphic from the company’s prospectus, shows the breadth of offerings:

If Tencent used chat as its wedge into making WeChat China’s SuperApp, Ant Group used payments to try to overtake its rival and claim the SuperApp throne.

In Ant Group: A Financial Infestation, Mario Gabriele and Lillian Li describe Ant’s strategy. Across Digital Payments, InsureTech, CreditTech, and InvestmentTech, Ant does three things:

Uses Data as a Superpower. Ant leveraged payments and transaction data into an unparalleled understanding of its customers, which it uses to inform credit and insurance underwriting, and which gives it the elusive actual data network effects.

Acts as Its Own First and Best Customer. Like Amazon, it builds its own products first to prove out the concept, test, and learn, and then uses the tech to build a platform on which others build. Theoretically, being a tech platform instead of a lender should have helped Ant avoid being regulated as a financial institution.

Aggregates Demand. By owning over one billion customer relationships, Ant was able to convince banks, mutual funds, and insurers to join the platform and use their own balance sheets to service customers.

Per Mario and Lillian’s analysis, Ant was on pace to do $21.6 billion in revenue in 2020, with net profit rates hitting 30% halfway through 2020. They also highlighted that between 2019 and 2020, the main source of revenue flipped, from Payments in 2019 to Credit in 2020.

Those kind of numbers make for a compelling IPO, and in The Ant That Poked the Dragon, Rishi Taparia set the stage as it looked in late October:

Ant Group is a financial services behemoth and the largest privately-held company in the world. It has over a billion users and 80 million merchants using its services across 200 countries. The platform processes over $18 trillion a year in payment transactions, making it bigger than Visa and Mastercard combined. The lending arm has lent over $300B to both consumers and SMBs. A big business ready for a big IPO.

Ant was scheduled to go public on November 5th, 2020; the $37 billion offering was to be the largest in history. The company was projected to have a market cap of over $300 billion, making them more valuable than most global banks. The demand for IPO shares was so high brokerages were holding lotteries to determine who would have the “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to buy in.

And then, as we covered at the beginning, Jack opened his mouth, Chinese banking regulators stepped in, and shit hit the fan.

On paper, what they were most concerned about was the fact that Ant was acting like a lender but regulated like a technology company. Ant claimed that it served as a platform, connecting lenders with borrowers and sprinkling in a little bit of algorithmic underwriting. The regulators weren’t so sure, and wondered whether Ant shouldn’t be treated like any other lender. That would mean two things:

Putting a cap on how much it could lend to consumers.

Requiring Ant to hold more cash on its balance sheet, and take risk instead of just matching borrowers with lenders.

According to the Financial Times, that would have had huge implications for Ant’s valuation.

The market didn’t have a chance to weigh in on what the regulations would mean for Ant’s business. On November 3rd, the IPO was blocked by the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock markets based on a direct order from President Xi.

Then, after two months of uncertainty and fear that the government would force Ant to break up, in late December, the People’s Bank of China told Ant Group to return to its roots as a payment provider and “rectify” its insurance, wealth management, and lending services, key growth and profit drivers for the business.

That leaves Alibaba investors with more questions than answers. What does “rectify” mean, for one. In the worst case scenario, Ant focuses exclusively on payments, which account for 36% of its revenue. That could potentially slash the company’s valuation by two-thirds, and Alibaba’s stake with it. Suddenly, what investors thought was a $100 billion position would be worth closer to $35 billion. Even in the best case scenario, with regulators watching the company and threatening restrictions, and with the black eye of a pulled IPO under its belt, it’s hard to see Ant achieving a valuation north of $300 billion.

Now, BABA investors are up in the air, with a pretty wide range for the value of its Ant stake: from $30 billion, or about 5% of Alibaba’s EV, to $90 billion, or 15%. Given the $219 billion drop in BABA’s market cap, the ultimate value of the Ant Group shares might be less important than how the relationship between the company and regulators progresses.

That’s the challenge with investing in China.

Investing in China

The same day the state announced potentially tighter regulations, state-controlled media company Xinhua posted a seemingly innocuous (and really fun-sounding) article titled, “Don't Talk Casually, Don't Do Things Casually, and People Should Not Be Casual.” In it, under the line “Everything has its costs, if you do not have the capital, please do not do whatever you want,” the publication included this painting of a horse in the clouds (Jack’s name, Ma Yun, means “Cloud Horse”):

That’s horse-head-on-your-pillow type shit, and serves as a reminder that with the CCP in charge, investing in Chinese companies is not at all like investing in American ones.

Despite the uncertainty, and perhaps even partially because of the discount that it provides, investing in China is tempting.

There’s the sheer size. At 1.393 billion people, China has the world’s largest population. According to McKinsey, the population is becoming much wealthier, with the Affluent and Upper Middle Class’ share of urban households expected to grow from 17% in 2012 to 63% in 2022, with the two groups’ private consumption growing at a roughly 20% CAGR over the decade.

Then there’s the internet penetration. In 2019, Chinese eCommerce sales grew 16.5% to $1.5 trillion, compared to $601.7 billion in the US, and that’s before the global pandemic that accelerated eCommerce penetration. And there’s still room to grow. While 90% of Americans are online, China’s internet population of 854 people represents only 61.2% of the total population.

Finally, there’s the innovation. Companies like ByteDance (TikTok’s parent company), Pinduoduo, and Bilibili have exploded into the western consciousness this year for their innovative business models. Chinese entrepreneurs no longer have the reputation they once did as copycats.

As a result, despite Alibaba’s struggles, the KraneShares CSI China Internet ETF, which tracks leading Chinese internet companies, has outperformed the NASDAQ over the past year.

And China’s run may just be getting started. Bridgewater, the $160 billion hedge fund founded by Ray Dalio, said in February 2020 that a group of seven “Asia Bloc” countries, led by China, are set to grow much faster than the US and Europe, and that the group will own a majority of the global stock market by 2035.

After Chinese regulators pulled the Ant IPO, Dalio, who calls himself “a chronic bull on China,” actually defended the government’s moves, citing a risk that innovation can get too loose. He also sees China evolving into the role of the world’s reserve currency since the US has created so much debt and printed so much money. That view on debt may be why he supports curbing Ant’s lending practices.

While Dalio is on the far right of the China bullishness spectrum, his view that westerners not owning Chinese stocks is too risky makes sense. As westerners, we’re naturally overweight American companies (for our jobs and the things we buy) and government. Adding China to the mix, if nothing else, is a hedge.

What to Do About BABA

If Dalio is right, and the government’s actions were actually rational and justified, and if Alibaba and the government come to a rational agreement, BABA is wildly undervalued. It’s the leading eCommerce company in an internet economy that is one of the largest and fastest-growing in the world, and owns a third of that market’s largest payments company.

Alibaba trades at a 72% discount to Amazon, and serves a market that is growing faster. It is running its patient, long-term playbook with Alibaba Cloud, and expects to start turning a profit on that business this year. It quietly powers a drop-shipping economy that has exploded during Coronavirus, and is likely to continue to accelerate as more influencers, who have audiences but no manufacturing expertise, build robust businesses around themselves.

Alibaba has some of the world’s strongest moats and important category leaders:

The world’s largest retailer by GMV.

China’s largest cloud provider.

A contender in the local O2O delivery wars.

The most ambitious logistics platform in the world.

The most complete understanding of the Chinese consumer.

Certainly, Alibaba faces genuine risks aside from the government. New, innovative eCommerce models threaten to upend what Alibaba has built. Pinduoduo, for example, is growing much faster than Alibaba is, and acquiring hard-to-reach rural customers with its vertically integrated social commerce model. ByteDance owns the world’s most powerful consumer attention algorithm, and could sell things to customers before they even think to go to Taobao or Tmall. New forms of interactive commerce will pop up to challenge Alibaba’s way of doing things, just like Jack challenged the old way of doing things. Core commerce margins will continue to compress in the face of competition, making it imperative that Alibaba figure out how to make Cloud and other new businesses profitable. And Jack is no longer there to lead the company through its next strategic crisis.

Those are all real risks that any company faces, and that Jack would embrace. “Competition is the greatest joy.” But there is a whole lot more than those normal risks baked into Alibaba’s discount.

My totally uneducated view is that Alibaba will come out of this with a slap on the wrist, and not a steeper, more existentially-threatening punishment. The ecosystem and network effects it’s built are so strong, and its positive impact on the Chinese economy so great, that breaking it up or worse is too risky a move. No one could move quickly enough to rebuild its ecosystem that the growth and quality of life of the average Chinese citizen wouldn’t suffer in its absence.

I have no idea whether, despite that, the government will still move to limit Alibaba (I have said all along, though, that the Trump Administration’s ban threats were empty), but at these prices, that’s a risk I’m willing to take.

Nothing in this essay is an endorsement of the Chinese government’s actions in this specific case, and certainly not more broadly. I am not qualified to comment there, except to say that with everything going on in the US right now, I’m glad to live in a country in which private citizens can silence our leaders more easily than leaders can silence private citizens.

But having spent so much time researching and following Tencent and Alibaba, I am incredibly bullish on the entrepreneurial spirit and talent in the country. Chinese entrepreneurs are not the government. Both Pony and Jack Ma started out with nothing but crazy ideas, and built two of the ten most valuable companies in the world. Their creations -- Tencent and Alibaba -- are two companies that I am going to keep buying.

If the market wants to give me a 73% discount to take on a little government risk, I’ll take it all day. Maybe I’m a little crazy, but so is Jack, and it’s worked well for him (I hope… Jack, if you’re reading this, just reply and let me know you’re OK).

Important Note: This is not investment advice. I am not a registered investment adviser. Everything in this essay is for learning and laughs only. I have a small position in BABA that I put on in the course of this research.

Thanks to Dan for editing, and to Dev helping me type it up.

We’ll be back on Wednesday, a Not Boring first. Keep your eyes peeled!

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Share this post