Who Disrupts the Disrupters?

Aggregators, Web3, and Disruption Theory

Welcome to the 602 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 45,460 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 The podcast will be out later today - I just finished writing at the last minute!

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… MarketerHire

Great marketing can be the difference between disrupting and being disrupted.

Great marketers can get your product in front of the right customers, while inexperienced marketers can burn cash and slow you down. But how to find marketers that are right for your goals?

MarketerHire matches your business with expert marketers perfectly suited for the task at hand. Brand, growth, email, and more, they have the right marketer for whatever you need. Even better? They do all the heavy lifting.

No one knows how to hire marketers better than MarketerHire: tell them what you’re looking to accomplish, and they’ll match you with the one right marketer for you. Set up a call with MarketerHire today:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

The deeper into Web3 I go, the more out of my depth I feel. Each one of these posts makes me more nervous to send than the last — I’m certain that I’m getting things wrong, that I’m painting an incomplete picture of something I don’t yet fully grasp. But I have so many questions that I’m trying to figure out, and I figure I might as well do it in real-time, so we can all learn together.

One question I’ve been wrestling with is this: is Web3 a really fun side show, or does it actually pose a threat to today’s seemingly untouchable tech giants? Today, we’ll try to figure that out. It’s the beginning of the exploration, and certainly not the end.

Before we get started, I want to take a second to call out how bad COVID has gotten in India, and point you to a place that I’m donating. If you’re interested in helping out, join me in donating to GiveIndia.

Let’s get to it.

Who Disrupts the Disrupters?

Disruption always looks obvious in hindsight. It’s hard to predict in real-time.

If you owned a newspaper in 2000, you couldn’t have predicted that Facebook, Google, and Twitter would crush you. Ditto for cable and Netflix, music and Napster, retail and Amazon, and on and on. This is the “next big thing will start out looking like a toy” idea. Even when the eventual winner launches, it’s nowhere near obvious that it will change the face of its industry, or an adjacent one.

As a thought exercise, imagine walking into a cable executive’s office in 1998, waving a red envelope in his face, and telling him he’s doomed. You would have gotten laughed right back out.

Now those companies -- the disrupters of the past 25 years -- are the large, powerful incumbents. They seem unstoppable.

Tech companies make up most of my portfolio. It’s hard to imagine a world in which those companies aren’t much bigger and more dominant in a decade then they are today. Are newspapers going to win back our attention from Facebook and Twitter? Is the record industry going to suddenly get its swag back and challenge Spotify? Are you planning on shopping in a mall any time soon?

No chance. Because we’re not going back to the old way of doing things, it’s hard to imagine what could topple today’s biggest tech companies. But that doesn’t mean they’re disruption-proof, just that it’s hard to imagine who will disrupt them. Disrupters are never re-disrupted by the companies they disrupted in the first place, and anyone who has tried to directly compete, on their terms, has failed.

But time marches forward. New disrupters enter the fray. Things that look like a toy become the next big thing.

So what could disrupt the internet giants? Web3.

I’ve become a little obsessed with Web3 recently. There is an endless amount to learn, and it changes daily. But it’s more than that. Web3 might represent the only threat to disrupt the world’s most powerful tech companies, the ones that make up most of my portfolio.

That idea has been floating around in my head, but Chris Dixon’s interview on Invest Like the Best a couple weeks ago snapped a few pieces into place. Web3 has the potential to be truly Disruptive, in the true, Clayton Christensen sense of the word.

We’ll mix some classic strategy theory with some future tech to figure out if and why Web3 poses a real threat to Web2.0’s giants, covering:

The End of the Beginning?

Big D Disruption

Revisiting the Computing Paradigm Assumption

Disrupting the Undisruptable

The State of Web3

Web2.0 Giants’ Web3 Comps

Our journey starts with a debate over whether the big tech companies can be disrupted at all.

The End of the Beginning?

In the opening days of 2020, when COVID-19 was just a sparkle in a bat’s eye, Ben and Ben engaged in a light spar over whether Big Tech could be disrupted.

On New Year’s Day, Benedict Evans wrote How to Lose a Monopoly. The piece is about the fact that companies lose power over time whether or not regulators step in to break them up. He points to IBM losing power to Microsoft, and Microsoft losing power to the internet broadly, and suggests that the leading internet companies may not be as unbeatable as they seem:

Today, it’s quite common to hear the assertion that our own dominant tech companies - Google, Facebook et al - will easily and naturally transfer their dominance to any new cycle that comes along. This wasn’t true for IBM or Microsoft, the two previous generations of tech dominance...

On January 7th, Ben Thompson wrote The End of the Beginningin response to Evans’ piece. Thompson argued that the current mobile and cloud leaders -- Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google -- aren’t going anywhere. To him, they represent the logical endpoint of a shift from batch computing in one server room to continuous computing everywhere.

If there’s nowhere to go past everywhere and always, he argues, there may not be a new generation of disrupters to replace today’s leaders:

The implication of this view should at this point be obvious, even if it feels a tad bit heretical: there may not be a significant paradigm shift on the horizon, nor the associated generational change that goes with it. And, to the extent there are evolutions, it really does seem like the incumbents have insurmountable advantages: the hyperscalers in the cloud are best placed to handle the torrent of data from the Internet of Things, while new I/O devices like augmented reality, wearables, or voice are natural extensions of the phone.

Both Evans and Thompson wrote about the companies that dominate all of tech, but a similar logic can be applied across categories within tech. What comes after you can do anything you want to do online -- listen to a song, watch a movie, connect with all the people, trade stocks, get a ride -- anywhere, anytime? It’s not just FAAMG that are safe in this view, but Spotify, Netflix, Twitter, Snap, PayPal, and any other category-leading consumer software company. (Even though it’s not exactly technically right, I’ll call this whole group the Aggregators for simplicity.)

Without a new computing paradigm on the horizon, are the Aggregators now immune to disruption?

Big D Disruption

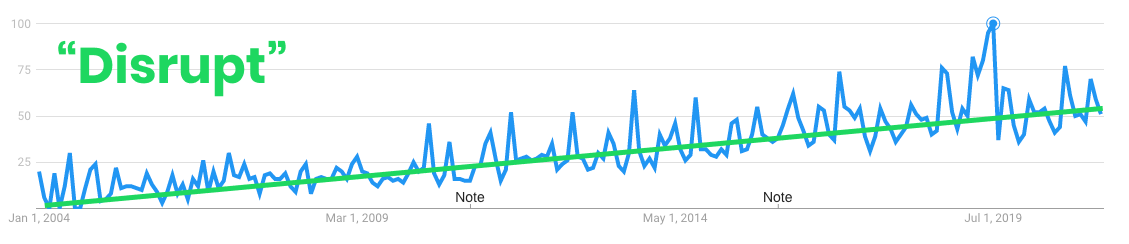

Every startup claims to “disrupt” something. Check out the Google Trends for the word “disrupt." It’s been on a steady incline since Google started “disrupting” the internet in 2004.

By the dictionary definition -- “drastically alter or destroy the structure of” -- many of the companies claiming to disrupt this industry or that are right. They’re coming in and doing things differently and changing their industry in some way. That’s little d disruption.

In business strategy parlance, though, Disruption has a more specific definition -- that’s Big D Disruption. In 1995, Harvard Business School professors Clayton Christensen and Joseph Bower coined the phrase “disruptive innovation” in a very 90’s-named HBR article titled Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Since then, the term has been so misused that Christensen penned a follow-up piece for HBR in 2015 to set the record straight. I’ll quote his recap here wholesale, bolds mine:

First, a quick recap of the idea: “Disruption” describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses. Specifically, as incumbents focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, they exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others. Entrants that prove disruptive begin by successfully targeting those overlooked segments, gaining a foothold by delivering more-suitable functionality—frequently at a lower price. Incumbents, chasing higher profitability in more-demanding segments, tend not to respond vigorously. Entrants then move upmarket, delivering the performance that incumbents’ mainstream customers require, while preserving the advantages that drove their early success. When mainstream customers start adopting the entrants’ offerings in volume, disruption has occurred.

Disruption is how little startups with modest resources compete against large incumbents with vaults full of cash: they find customers the incumbents ignore or overserve (and overcharge), build “good enough” products for them, and then expand into the mainstream as they improve their products.

Today’s tech giants aren’t as easy to disrupt as Xerox or the newspapers, though. The people running Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Google, Spotify, Netflix, and the like have read Christensen. They haven’t done what incumbents have traditionally done: “improved their products and services for the most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers.” (Apple is an exception on the hardware side, although it’s been upmarket for a long-time and has yet to be disrupted.) They don’t ignore less profitable consumers because the internet, with high fixed costs and near-zero marginal costs, rewards companies for serving every consumer.

The more consumers companies can spread their fixed costs over, the more profitable they become. Facebook is free, as are its subsidiaries, WhatsApp and Instagram. It monetizes through ads, with near-zero marginal cost to serve them. More eyeballs, more profit. It would cost nearly $100 million to individually purchase all of the songs that you can listen to on Spotify for $9.99 per month. Amazon famously views your margin as its opportunity.

In Beyond Disruption, Thompson argues that when Christensen wrote Disruptive Technologies in 1995, it was the pinnacle of management theory (emphasis his), but that because of the nature of the internet, it no longer works:

Many of the most important new companies, including Google, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Snapchat, Uber, Airbnb and more are winning not by giving good-enough solutions to over-served low-end customers, but rather by delivering a superior experience that begins at the top of a market and works its way down until they have aggregated consumers, giving them leverage over their suppliers and the potential to make outsized profits.

Internet giants can move upmarket and downmarket at the same cost, giving every consumer the same great experience, and amassing consumers who they can use to bend the will of suppliers. That’s the point of Thompson’s Aggregation Theory.

Use demand to get power over supply, thereby lowering costs and increasing profits. How does a new entrant compete with that? How do you low-end disrupt a company that provides an excellent experience at no cost to every consumer?

Thompson might argue that you don’t. In two separate articles, five years apart, he made two separate arguments that suggest that today’s internet giants are undisruptable:

You can’t low-end disrupt Aggregators because they serve every consumer segment well and cheaply.

Even if a new computing interface comes along, the incumbents are still in the best position to take advantage.

Maybe this really is the end of the beginning…

But you know that’s not how I feel, because we’re less than 2,000 words in. This is just the beginning of the beginning.

Today’s tech giants are more vulnerable than they look. They’re not going anywhere tomorrow. They’re probably very safe for the next five years. But over the next decade and beyond, one or more of today’s category-leading tech companies will be overtaken by a crypto-native competitor.

Revisiting the Computing Paradigm Assumption

To understand why, let’s start by revisiting that assumption that mobile/cloud is the last major computing paradigm. Chris Dixon kicked off his Invest Like the Best interview with a dismissal of the Thompsonian view:

Sort of an obvious question if you're in technology or investing like I am is, "What's next?" One possibility is sort of it's the end of this cycle, it's a mature industry now. If you look at other industries, electricity and cars and other things, there was a period of rapid change and then at some point they stabilize. That's one hypothesis. I don't believe that, but that's one view you could have…

I believe, personally, that the most exciting new computing wave is blockchains and crypto.

Thompson’s confidence in the incumbents was based on the idea that even if new input/output (I/O) devices like wearables, voice, or AR replaces the phone, the incumbents are still in the best position to capture the opportunity. Facebook doesn’t care if you scroll the feed on your phone, AR glasses, or VR goggles -- it will serve you its feed, and the ads that support it, anywhere, anytime. It might even sell you the devices. The front-end is relatively meaningless; the incumbents are still best-positioned on the back-end.

But Thompson missed Web3 in his list of potential threats, and Web3 changes some important things that the incumbents are not best-positioned to handle.

To start, blockchains are not just a new I/O device. They aren’t devices at all. They represent a new paradigm.

Blockchains and crypto let you do things that previous computing paradigms couldn’t, the most important of which, according to Dixon, is that you can “write code that makes strong commitments about how it will behave in the future.”

No one person or company can change the rules. There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin, no matter what anyone tries to do to change that. Strong commitments extend far beyond bitcoin, to Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), Decentralized Finance (DeFi), Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), and new blockchain-based products no one’s yet dreamed up.

If the code can make strong commitments, you don’t need central platforms to make and enforce the rules. They just create economic drag. Instead, you can allow creators and consumers to share more of the profits that Aggregators and Platforms previously captured.

Blockchains can make commitments to developers, too. Unlike Apple’s App Store, or Facebook, or Twitter, the rules are known from the start and they don’t change when a company decides it needs to increase profits. If you’re building a new app on top of the Ethereum or Solana blockchains, you know what you’re getting. You can plug into a growing number of superpowers with confidence that they’ll always be there, even if the people behind them go away.

That changes everything.

Disrupting the Undisruptable

Disruption comes in two forms.

Low-End Disruption: Serving consumers who are overserved by incumbents, typically at a lower price point with a “good enough” product.

New-Market Disruption: Creating a market where none existed by turning non-consumers into consumers.

Traditionally, disrupters observe the state of the market, identify overserved or unserved consumers, and jump in to steal demand the incumbents don’t want. Remember, though, that the Aggregators want all of the demand. They want to serve everyone well, at the lowest possible cost. They haven’t left an opening.

Sometimes, though, a new technology creates an opening where none existed.

In a 2016 HBR piece, What Would it Take to Disrupt a Platform Like Facebook?, Joshua Gans wrote:

Supply-side disruption arises when a new innovation or technology offers a better way of providing consumer value than the old technology does...

Blockchains and crypto are the new technology that offers a better way of providing consumer value than the old technology does. It’s the computing shift that Thompson missed and Dixon picked up on. Blockchains aren’t a new I/O device, they’re a fundamentally new back-end on top of which “a smaller company with fewer resources” can build products that scale and evolve rapidly.

Blockchains and the ecosystems on top of them allow entrepreneurs to build huge projects with very lean teams. It comes down to scalability and composability.

My friend Jon Wu pointed out that a lot of the work a normal startup would have to do gets handled by the blockchain itself, by other protocols, and by the community:

The blockchain handles the rails - security, how the transactions settle, movement of money, etc… that removes the scaling headache for a young company.

Projects like Metamask remove the need for account creation - just connect your Metamask and you’re in, along with your money.

You don’t need customer service because people understand that it’s self-custody, and if you send your crypto to the wrong place, that’s on you. There’s literally nothing a customer service team could do to fix that anyway.

Early users are also investors and community members, and do much of your marketing for you.

Other projects built on the same protocol become “legos” that you can snap into place to add new functionality to your product.

Simplifying it, he said, “You focus on your core value proposition, and the Ethereum chain takes care of everything else.”

As a Web3 startup, you have scale from day 1, because you borrow the blockchain’s scale. As a result, Web3 companies can be like API-first companies on steroids. They can focus on what they do best and outsource everything else to the chain, and to other protocols. Scalability and composability.

That should be terrifying to the incumbents. Built-in scalability, composability among protocols, and programmable money are a formula that might allow Web3 projects to low-end disrupt the seemingly undisruptable.

Low-End Disruption

Recall that “Entrants that prove disruptive begin by successfully targeting those overlooked segments, gaining a foothold by delivering more-suitable functionality—frequently at a lower price.”

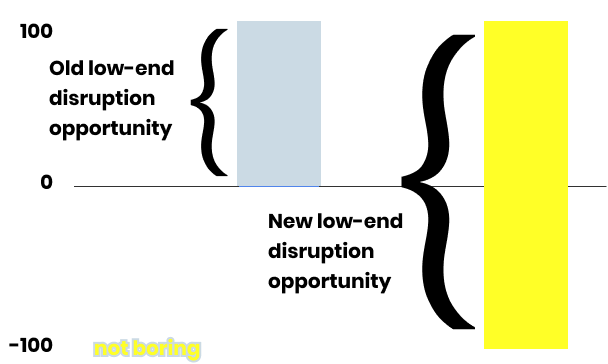

While the Aggregators definitionally serve nearly everyone, they actually do overlook a segment of their users: the people who aren’t happy to just use the products for free, but who want to earn ownership, privileges, and money for their participation, and who are willing to accept a lower-quality user experience to get those things. This is where they’re susceptible -- while they generate tiny profits on each user, they’re not willing to go negative and actually pay those users.

So how do you low-end disrupt a high-quality, ultra-low-margin or even free product? How do you get a price lower than the $0 they’re paying today? You go negative; you actually pay people to use the product, in a currency that gets more valuable as more people join.

Web3 lets developers write money into the code itself, and to program smart contracts that automatically pay people out for doing things that are beneficial to the product. It pays users and gives them upside, automatically, based on pre-set rules. That makes it possible to low-end disrupt even free products.

That’s massive. It flips everything on its head. And it’s a huge opportunity for Web3 projects: because the users and owners are often the same people, and there’s no middleman, there’s a whole pool of money that can be used to attract participation.

Web3 blends the lines between creators, consumers, suppliers, and investors, and lets projects pay people to use them, whether directly or via tokens that might grow in value over time. That diminishes the value of aggregation by creating a shared set of incentives between supply and demand.

Baking in payments to early adopters and aligning their incentives with a protocol or project’s long-term value is a potentially massive advantage, and can provide the activation energy to help kick off the seemingly-impossible process of disrupting the disrupters. As Wu told me:

Part of the reason the space is fascinating is that feedback loops are really tight. Because oftentimes the users are investors, actions are self-reinforcing, and you can quickly get into virtuous loops if you start people off on the right foot.

Fast-spinning virtuous loops, aka flywheels, might give projects the escape velocity they need to challenge the incumbents despite their strong network effects.

Imagine going to Disney World, and getting shares in Disney, the company, every time you took a ride, bought Mickey Merch, or sent your friend a picture. Or that owning shares in Disney let you skip all of the lines as long as you held the shares. That’s what tokens do.

“Tokens” sound almost too game-like to be meaningful, like something you use at Chuck E Cheese, but they’re like those hypothetical Disney shares: you earn tokens for investment, participation, or work and they give you upside, privileges, votes, or a combination of all three. Tokens sound lighter than shares, less serious, but in reality, they can be much more powerful.

By compensating users for positive participation, Web3 projects can build up energy that might become strong enough to carry them from the early niche to the mainstream.

New-Market Disruption

Web3 also enables previously-impossible products and creates new-market footholds. Christensen wrote, “In the case of new-market footholds, disrupters create a market where none existed. Put simply, they find a way to turn nonconsumers into consumers.”

This is happening all over Web3. As three examples:

NFTs: Making digital objects scarce has unlocked new creators and new consumers. Digital artists are quitting their job to create NFTs and people who would never buy physical art are becoming collectors. It’s early and toy-like today, but it’s the first example of Web3 jumping into the mainstream and enabling entirely new behaviors.

DeFi: Most DeFi projects just wouldn’t be possible on traditional financial rails. Hxro, for example, lets people trade options with expirations in as little as 5 minute increments that settle instantly. Staking, locking up your coins to provide liquidity, is a new crypto phenomenon, and “validator” is a role that never existed before. This means new people consuming new financial products in new ways.

Bitcoin: Bitcoin turned millions of people across the world into investors for the first time -- there are currently over 34 million wallets with at least $1 worth of bitcoin -- and created a new generation of wealthy consumers.

This is a meta-advantage that crypto has: its new-market disruption didn’t just turn previous non-consumers into consumers of a narrow new thing -- like personal photocopiers let anyone make copies at home -- it turned previous non-consumers into very rich people willing and able to consume, participate, and invest across the spectrum of new Web3 projects and products. It may be the greatest source of ultra-wealthy individuals in the history of the world.

In a January 2020 blog post (I’m sensing a theme), Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong wrote:

Olaf Carlson-Wee and Balaji Srinivasan estimate that at a price of $200,000 per Bitcoin, more than half the world’s billionaires will be from cryptocurrency.

These are people with the resources to pull promising new Web3 projects off the ground, with a set of values more aligned to the new way of doing things than the old, who have made so much money so quickly and easily that they’re willing to stake a lot of it to see the world develop the way they want.

Plus, it’s global by default, offering opportunities for both creation and consumption to people who were previously left out.

A ton of money + scalability + composability + incentive alignment + entirely new capabilities might be a disruptive formula, but it’s early. There’s a lot of work left to do to get from where we are today to toppling Facebook.

The State of Web3

Just because it’s theoretically possible for Web3 projects to disrupt the big incumbents doesn’t mean that it’s guaranteed, or that it’s even close to happening.

Right now, many Web3 projects feel like they’re very much in the “good enough” phase in which many disrupters begin -- they can’t match Web2.0 projects on usability, performance, or cost, but they come with advantages that matter to a small niche. That’s OK, that’s how disruption works. But the next step after winning the early adopters is to improve the products enough to go mainstream.

That starts with improving UX and lowering costs. Building on Ethereum lets developers do all sorts of novel and potentially disruptive things, but the reality is that the UX is typically confusing and hard for all but the most hardcore to use. And the gas fees are too damn high.

One of the biggest challenges for Web3 entrepreneurs currently is that Ethereum, the Layer 1 protocol (aka blockchain) on top of which many of the most exciting projects are being built, uses a proof-of-work model that limits it to 15 transactions per second, at $15 per transaction, with 5 minute latency, and huge energy requirements that hurt the environment.

Slow and expensive is fine for big ticket items. No one’s going to mind paying $10 in gas fees on an NFT that sells for millions of dollars. But it limits what can be built. For example, I split part of the proceeds from the Power to the Person NFT sale with anyone who retweeted the announcement, but the fees for them to claim their rewards were higher than the reward itself. High fees limit the types of microtransactions necessary to build money into every action.

The infrastructure is constantly improving, though.

Ethereum itself is currently undergoing a transition to Eth2, which will switch it from proof-of-work (a bunch of computers race to solve math problems using a lot of computer power) to proof-of-stake (computers take turns validating transactions based on token ownership). That, plus sharding, or splitting the infrastructure into smaller pieces working simultaneously, will make it faster and cheaper.

Meanwhile, newer blockchains like Solana, Binance Smart Chain, and Polkadot offer different capabilities and performance levels.

The fastest-growing is Solana, which uses a mechanism called Proof of History, a cryptographic time stamp, plus Proof of Stake to dramatically increase speed and lower costs. A transaction that might cost $10-15 and take a few minutes on Ethereum costs less than 1 cent and takes less than 1 second on Solana. Solana only launched last March, and has already attracted a ton of developer interest. Projects like decentralized exchange Serum, time-based derivatives market Hxro, and massively-multiplayer metaverse Star Atlas are all built on Solana.

As more and more legitimate blockchains emerge, developers will need to figure out interoperability among them. Mainstream users don’t care which blockchain they’re on, they just want whatever they do to work, anywhere, like it does on the internet.

As blockchains improve and connect, new possibilities are unleashed. Better Layer 1s (blockchains) mean better Layer 2s (apps) on top of them. As improvements make it faster and easier to use crypto, more money is entering the system.

So far, that’s showed up directly in financial products. DeFi in particular has taken off over the past year: growing from $867 million USD in Total Value Locked (TVL) to $58.4 billion. In a year. TVL represents the value of the actual USD, ETH, BTC, or other coins currently staked across all DeFi protocols, and it shows that people are putting real money to work in DeFi.

DeFi’s growth poses a threat to traditional finance (TradFi). It offers faster settlement, access to more exotic products for regular investors, seamless cross-border transfers, and inflation protection, among other benefits. If the response to my BlockFi post was any indication, people want better ways to put their money to work for them.

The question is: are speculation and investment the blockchain’s killer use cases, or will the same mechanics that have caused DeFi’s ascent give rise to Web3 projects that can topple the Aggregators?

Web 2.0 Giants’ Web3 Comps

It’s starting to happen. NFTs were the first sign that Web3 adoption is moving beyond DeFi. Millions of dollars spent on digital art and collectibles grabbed the headlines, but even as the frenzy cools, the toolkit that lets people create scarce, ownable, tradeable, and monetizable media will have a lasting impact.

Source: NonFungible.com

NFTs are another building block, another way that Web3 is able to serve consumers and suppliers in ways that Web2.0 can’t. It’s another sign that Web3 might disrupt the Aggregators.

Some disruptor candidates are beginning to emerge. There are an increasing number of projects beyond DeFi that combine Web2.0 usability with crypto’s back-end powers. These projects represent some of the first demonstrations that Web3 is going to be about a lot more than finance; it’s coming for everything.

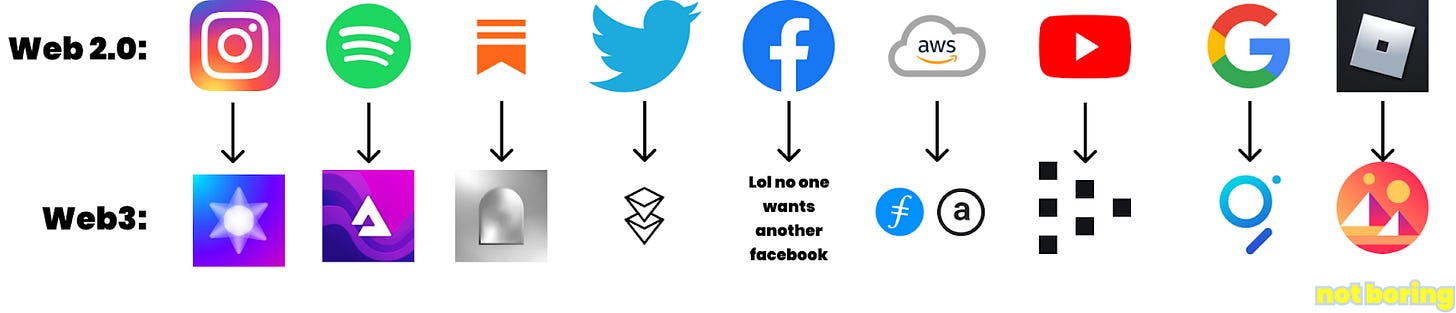

There are direct Web3 analogs for nearly every Web2.0 giant.

If you were to look forward from the late 1990s or early 2000s, it would have been much easier to predict that the internet was going to disrupt offline businesses than which internet businesses would win. The same is true in Web3.

To be sure, some of these products are overly-skeuomorphic representations of their Web2.0 predecessors -- take an old idea, add some crypto mechanics, and voila.

Bitclout, the controversial Web3 Twitter competitor, literally looks like a more poorly-designed version of Twitter, complete with hearts, retweets (which they call reclouts), and replies.

The big difference: you can buy your favorite influencer’s coin, and make money as other people buy their coins, too. As an influencer, spending more time on the platform means a higher likelihood that people buy your coin, which means more money or pride or something. I’m skeptical.

But other projects are more thoughtfully designed, focusing on the new experiences that Web3 tech lets them build from the ground up.

Audius Projectis a community-owned music streaming and sharing platform that lets artists own and monetize their work and gives fans access to artists and premium features by owning the $AUDIO token. Plus, all $AUDIO holders govern the project’s future. Because it focuses on remixing, it bills itself as an alternative to Soundcloud, but it’s possible to imagine a platform like Audius competing with Spotify down the line by attracting musicians who want to own their music and connect more directly with fans. Given the complexity of music rights, it will take the system a long time to sort itself out, particularly for back catalogs, but nearer-term, platforms like Audius might start stealing artists away from the traditional record label model. Spotify is one of the more decentralized public companies; I wouldn’t be surprised to see them get involved with Audius or launch their own crypto tools.

Mirror, which I used to Mint, Auction, and Split the Power to the Person NFT, is a publishing platform that gives writers crypto tools. Mirror, which just started welcoming writers in December, already lets writers own their own domain (using ENS) and content (using Arweave), crowdfund posts, mint posts as NFTs, auction them off, and split the proceeds. Similar to the DeFi concept of “money legos,” Mirror is building and using media legos that give writers the power to do all sorts of things they can’t do on Substack or Medium. While Mirror is most directly a threat to replace those two platforms over time, it also represents a challenge to legacy publications like The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Part of those companies’ advantage is that they fund stories independent writers can’t and provide resources like editing and distribution that individual writers can’t on their own. Crowdfunding may help solve the former, and I bet Mirror will experiment with DAOs that let writers pool resources.

The Graph indexes Web3 and makes it searchable. It’s like Google for Web3, but instead of one company indexing and ranking all of the internet’s data, The Graph relies on a decentralized network of Indexers and Curators who are financially incentivized to uncover and index relevant subgraphs, and provide correct data to Consumers. Consumers pay directly for that data. The Graph also lets any decentralized app build on top of its APIs to deliver data to end users. It’s a more open and financially-aligned alternative to Google’s ad-based model.

BitClout, Audius, Mirror, and The Graph are just a handful of projects using Web3’s built-in scale, composability, and built-in money to put value back in the hands of creators and consumers. They’re early.

Looking at the products today, it seems inconceivable that The Graph would actually knock off Google, or that BitClout could take down Twitter. And chances are, those particular products won’t. WebVan had to die so Instacart could fly. Ditto for MySpace and Facebook, AskJeeves and Google, and Pets.com and Chewy. It would have been easy to dismiss the internet because of the roughness of its earliest products, but the powers built into the internet sowed the seeds for inevitable disruption.

While early Web3 projects don’t seem close to knocking off the Aggregators today, they benefit from speed, compounding, and composability. Those factors combined to take DeFi from nothing to $58 billion in a little over a year, and they’ll do the same for non-finance Web3 projects. As the underlying blockchains improve, the protocols built on top of them improve. As new builders build new things, they provide more building blocks for everyone in the ecosystem. And as more consumers become consumer-investors, more people are incentivized to bring more people into the ecosystem, accelerating mainstream adoption.

The internet allowed disrupters to deliver products more cheaply at scale. Disruption was inevitable, even if its form was unclear.

Web3 allows a new generation of disrupters to create products that actually pay people to use them, and aligns the incentives of creators, consumers, suppliers, and investors. Disruption is inevitable, even if its form is unclear.

For further reading on Web3, check out some of the other pieces I’ve written recently:

Thanks to Jon for the brilliant input and feedback, and to Dan for editing.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday for more crypto,

Packy

Packy: this piece is incredible. My belief is that this particle essay will go on to become a seminal work in the history of the emergence of Web3. As someone who works in the traditional media world, it is my belief that the shift away from the TradMedia model (of aggregators/platforms HOARDING all of the ad revenue) to the DeMedia model (of creators sharing the financial upside/monetization of their creative works with their early supporters, fans, evangelists, and customers), will lead to a class of “consumer-investors,” as you say. Though people like Chris Dixon (and other Web3 champions) keep using terms like the “Creator Economy” and the “Ownership Economy,” perhaps a better term for what will emerge is the “Community Economy.” The TradMedia framing of “creators” vis-a-vis “fans” (or “customers,” “listeners,” “subscribers,” or “consumers”) will be properly reframed as Community Leaders and Participating Community Owners. This is the inevitable future. Congrats on a fantastic piece!

Packy, thanks for the great writing. Great to see 3 of my favorite writers all mentioned here. One thing has been bugging me for a quite a while, which is that early backers or token holders naturally promoting / marketing their tokens. This is a definite alignment of incentive and reward for early backers / users. Chris Dixon in the aforementioned podcast said something along the lines of this being completely normal in capitalism.

But I was wondering whether that is actually true. I thought why many people frowned upon multi-level marketing or ponzi scheme was because of the very model that sellers take a cut whenever the people the seller brings in sell something to someone else. Though not fully equivalent, early backers promoting their own invested tokens, strictly speaking, has an element of that.

I thought the reason why word of mouth was so powerful in making people adopt any product was because people genuinely liked the product, not necessarily because they had financial incentive to gain. All in all, I'm a little skeptical (and scared) about embedding financial incentives to every aspect of our lives.

It would be great if you had some thoughts around here, and I would love to learn more!