While Zoom Zooms, Slack Digs Moats

What Zoom, Slack, Drinks, and Weddings can teach us about growth vs. moats

Welcome to the 138 new subscribers since Monday’s e-mail! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed yet, it’s easy! Just sign up, sit back, and enjoy, and maybe even learn a little bit.

Hi friends 👋🏻,

Happy Monday, and a very happy belated Mother’s Day to the moms out there!

A Note on Memory

As I've written about here before, I have a pretty bad memory, and my biggest fear in life is losing it.

Last week, I wrote about the idea of Shotcallers vs. Worldbuilders. An hour before I hit send, Dan Teran pointed out that Ray Dalio wrote about similar concept called "Shapers" in Principles. Afterwords, Kyle Schiller shared Peter Thiel's version, "Definite/Indefinite Optimists," which he wrote about in Zero to One.

When Dan and Kyle brought them up, it was like I was hearing them for the first time. But I wasn’t. I've read both of those books.

On the one hand, it depresses me to think that I've spent so much time reading books and can't even remember concepts that I find interesting enough to write thousands of words on. If this isn't a reason to get more consistent with my Readwise usage, I don't know what is.

On the other hand, I've always thought (hoped) that all of those things that I read but couldn't recall were floating somewhere in my head, not accessible by name, but part of a growing corpus of ideas that I had conceptual access to. I'm sure there's a name for this phenomenon, and I'm sure I've read about it multiple times, but I can't remember.

One of the best parts about having such smart people read what I write every week is that you can all call me out when I forget. Keep doing it. You can bet that I'll never forget "Shapers" or "Definite/Indefinite Optimists" again.

Anyway, with that personal caveat out of the way, let's get to it.

Hitched to Slack

For this setup to work, I’m going to need to to reach a few months back in your memory, back when people made plans to hang out in-person. Ready?

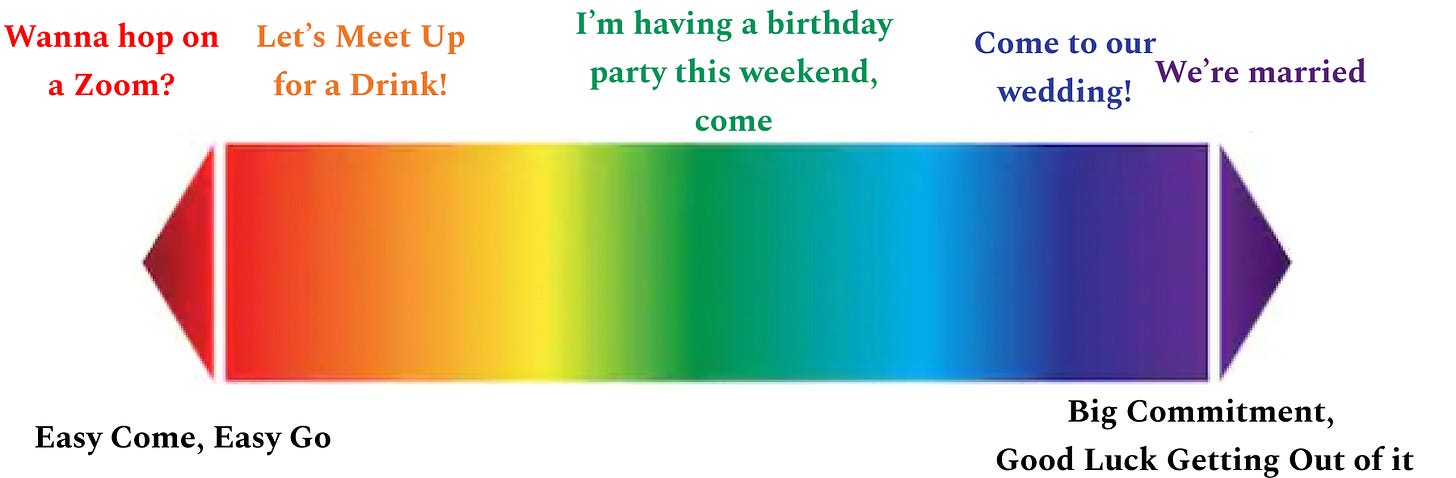

Hangs came in all shapes and sizes. On the one end of the spectrum, there was “Let’s meet up for a drink!” and on the other was “Come to our wedding!”

“Let’s meet up for a drink!” was fun, casual, and easy. You found a time that worked for you and your friend, picked a place to meet, showed up, ordered a drink or two, paid, and left. You might have even told other friends to swing by if they were in the neighborhood, no pressure! You could do drinks with multiple people over the course of a week, or even within the course of one night. Easy breezy.

If something came up - a work project took more time than you thought, someone cooler invited you to drinks - it was pretty easy to cancel casual drinks. “So sorry to do this, but I’m stuck at work :( Any chance we can reschedule for next week?” Rumor has it you could even say you were stuck at work when you weren’t.

It was easy to say yes to drinks, because the yes was just a placeholder.

“Come to our wedding!” was a commitment. You picked a date a year in advance, booked a venue, organized caterers, picked flowers, booked a DJ, signed up a priest, planned a welcome party, reserved a block of hotel rooms, reserved a block of cheaper hotel rooms, and convinced hundreds of your closest friends and family to spend thousands on travel and gifts and take a day or two off of work to come celebrate the happiest day of your life. Nothing chill about it.

Imagine canceling a wedding. Everyone you know was already planning on coming and has put money down, you had a network of venues and vendors plugged in and partially paid, and the thought of having to do all of that planning and inviting again gave you nightmares. Plus, it’s going to be a fun wedding! It would take some crazy, very unlikely event to get you to cancel, like a global pandemic or something.

You had to think long and hard before deciding to have a wedding, because once you went through with it, you were locked in.

Drinks and weddings… am I in the right place?

Wondering why I’m talking about drinks and weddings in a strategy newsletter?

People lump Zoom and Slack together as “WFH” stocks, but they’re different.

Zoom is “Let’s meet up for a drink!” It’s easy to set up, and equally easy to cancel.

Slack is “Come to our wedding!” It’s a real commitment, so it takes some real thought to say yes. Once you’re in, though, you’re in.

I want to state this up front: I really like Zoom, as a product and as a business. This is not a Zoom hit piece. It’s an exploration of why Slack’s stock should get the same or greater lift from Covid as Zoom’s and a good chance to study some foundational business strategy concepts.

Zoom Zooms While Slack Slacks

Last Wednesday, Ben Thompson wrote a piece titled Zoom’s “Genuine Oversight”, Zoom’s Strengths and Weaknesses, Virality Versus Network Effects. Reading it felt like that thing that happens when you say something and Instagram serves you an ad for it 30 seconds later.

My brother Dan and I have been talking about this idea for weeks. We strongly believe that long-term, Covid will be better for Slack than for Zoom. (Full disclosure: we both own shares in Slack.)

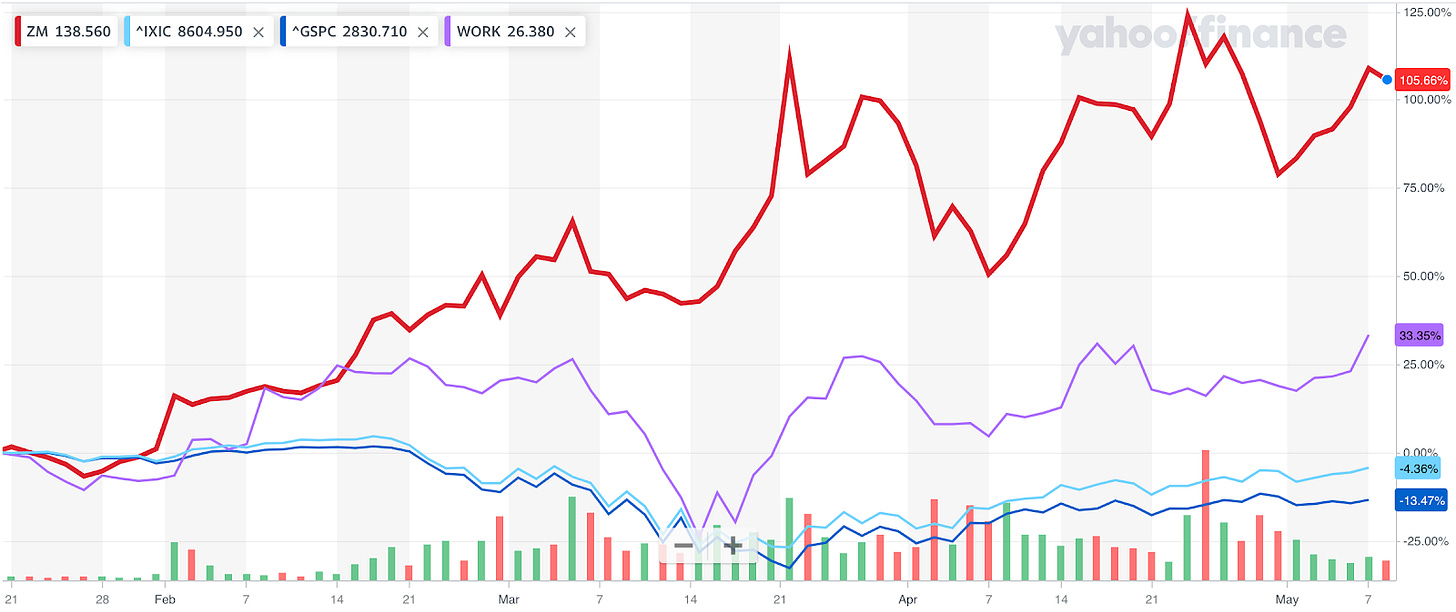

Until last Thursday and Friday, when Slack’s stock finally broke $30, the market did not agree with us. Since the first confirmed US Covid case on January 21st, Zoom’s stock price is up 106%. Slack’s is up only 33% (more than half of which came in the two trading days since I started writing this).

As Slack fell below $17 in mid-March, I felt like Carrie Matheson in Homeland: “I have never been so sure, and. so. wrong.”

But I get it. In the near-term, the numbers look better for Zoom. It doubles revenue each year, is already profitable, and over the past three months, has grown like crazy.

In a matter of weeks, Zoom zoomed from 10 million users to 300 million users participants, about which Thompson wrote:

This all [the security issues] might not matter if Zoom were able to use the massive surge in usage to create network effects that lock users into the service. That’s the thing though: Zoom is so popular and so viral in part because it has no network effects. Only a host needs an account; everyone else just clicks a link.

Slack, on the other hand, doesn’t look quite as good on paper. It is not quite doubling year-over-year, it’s not profitable yet, and it’s growing more slowly than Zoom is.

It has not gone as viral in part because its specific network effects are too strong for rapid corporate adoption. You can join a Zoom with a link, but a company basically needs to onboard all of its employees if it wants to use Slack to communicate. Plus, Slack is mainly a B2B product, while Zoom serves (and counts in its 300 million figure) both B2B and B2C. As a result, Slack’s growth has been excellent but not as eye-popping as Zoom’s.

On March 25th, 55 days into Slack’s off-cycle Q1, CEO Stewart Butterfield tweeted:

and

Sure, 12.5M isn’t as impressive as 300M. But the beauty of Slack is that those 12.5M+ daily active users (DAUs) and 9,000+ new paid accounts are locked. They will keep paying for years.

Which brings us back to what drinks, weddings, and business strategy.

In 2016, Hamilton Helmer wrote 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy. It quickly became a modern strategy classic.

7 Powers describes seven ways businesses can build moats. Like their castle-surrounding namesake, these moats protect a business’s profits from competition. The seven moats/powers are:

Economies of scale

Network effects

Counter-positioning

Switching costs

Brand

Cornered resource

Process power

To understand all seven, I highly recommend reading the book or at least Florent Crivello’s excellent summary. To compare Slack and Zoom, we only need two: Network Effects and Switching Costs.

Network Effects

One of the things that makes a wedding so special, and so hard to cancel, is that it involves everyone you know and love. With some exceptions (Aunt Edna), each RSVP “yes” means that the wedding is going to be even more fun. That’s a network effect.

“Network effects” is an overused concept. The basic concept is that network effects occur when an experience gets better with each person who joins. Because investors love network effects, every startup at some time or another tries to claim that they have them. For example, an online retailer might say that it has network effects because more users means that they can sell more SKUs, and selling more SKUs benefits all users, ergo the experience improves as more people join. That’s not a network effect.

The VC firm NFX (literally named after network effects), wrote a post spelling out the thirteen types of… nfx. Zoom doesn’t fit any of them, Slack fits two.

1. Personal Utility (Direct)

When Thompson says that Zoom has virality but not network effects, he means that Zoom does not get better for each user as more people join Zoom. As long as one person you know has it, everyone else can just click a link to join. That makes Zoom super viral - 1 person with an account can get 100 people to use the product at once! - and makes a stat like 300 million participants possible.

Arguably, Zoom’s virality has caused negative network effects, at least for me. The more people who join Zoom, the more Zoom happy hour invites I get, the worse my life becomes.

Slack, on the other hand, has Personal Utility (Direct) network effects inside of a company. People use PU(D) networks for essential communication with their personal or professional circles using their real identities.

As a company’s Slack usage approaches 100%, it becomes possible to replace e-mail, those awkward texts from your boss, and even meetings with Slack. As more people in the company use Slack more often, using Slack becomes more valuable and not using Slack becomes a career risk. Abstaining means missing information that is important to your job. Relatedly, not buying a seat for any employee signals that that employee isn’t as important as those who are on Slack. It’s easier just to pay the $6.67 per month.

In fact, this effect is so strong that the decision is most often binary - either everyone in the company uses Slack, or no one does.

In this sense, Personal Utility (Direct) network effects within a company are a double-edged sword. This is why Slack’s user growth is structurally much slower than Zoom’s. There is no lightweight way to do Slack as a company, no “Let’s meet up for a drink!” But it’s also why Slack is so sticky. Like a wedding, it requires commitment, but once a company says, “I do” to Slack, it isn’t going anywhere for a long time.

2. Platform (2-sided)

Slack’s stock has dragged because of the market’s concern that Microsoft Teams would prevent Slack from winning large enterprise accounts. I think the narrative is overhyped, that Microsoft’s daily active user numbers are inflated, and that Slack will be able to win large enterprise accounts. (See: IBM, ViacomCBS, Uber) That’s a conversation for another time.

What’s germane to this essay is that Slack is running the old Microsoft playbook. They’re building Platform (2-sided) network effects, which occur when developers and users provide benefit for each other via a particular platform, while the platform itself provides value for both sides. Think iOS and Android, which both have app stores to connect developers and users.

Microsoft is the OG in this space, having created Platform (2-sided) network effects with the Windows operating system. Users made Windows valuable to developers, who in turn made Windows valuable to users, and so on.

Similarly, Slack has build an ecosystem of apps on top of its platform. The company has encouraged app integrations, not only by opening up its API and creating an app directory, but also by raising the $80 million Slack Fund to invest in companies building on top of Slack. Slack has the users, so developers build for Slack. Developers build for Slack, so Slack has more users.

(Note: Microsoft also has a Teams app directory, but it’s a mess. They don’t need the product to be great to sell it to existing clients.)

Like a wedding DJ or caterer who enables the bride and groom to offer a better experience to their guests, Slack’s app ecosystem means that users can do more with Slack than Slack is able or willing to build itself.

Zoom, on the other hand, is not a platform. It does have an integration directory, but those integrations are mainly about being able to schedule Zoom meetings from inside of other products.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing! Zoom’s simplicity and performance are two qualities that have allowed it to grow as quickly as it has over the past three months. The flip side of that, though, is that Zoom does just one thing and has opened itself up to attack from competitors big and small - Microsoft/Skype, Facebook, Google Meet, Houseparty, Whereby, and many more startups that are springing up to meet specific use cases uncovered by the Covid quarantine.

Thompson was right. Zoom has virality but not network effects. Slack, on the other hand, has two forms of network effects. Its network effects make it harder to join, but nearly impossible to leave.

Switching Costs

On Thursday, I had a Zoom in the morning, a Google Meet in the afternoon, and a Houseparty happy hour. Like canceling drinks with a friend or hopping from one bar to another, switching off of Zoom is too easy.

Zoom suffers from low switching costs, which Helmer defines as “the value loss expected by a customer that would be incurred from switching to an alternative supplier for additional purchases.” If a user decides to shift to another video conferencing product because of price, performance, security, or any number of deciding factors, they don’t incur large costs. They simply send out a different link the next time they want to meet over video.

This hasn’t been a problem for Zoom yet. Zoom has actually retained its customers incredibly well. Its net dollar retention rate is an industry-leading 140%, meaning that it makes 40% more in year 2 from the group of customers who signed up in year 1, even after accounting for churn.

Zoom is able to retain and grow customers for the same reason so many people have started using it during the quarantine: its product is the best.

That’s the tricky part about moats; they might not matter for a while. There are very good reasons for a startup, constantly resource-constrained and forced to make trade-offs, to ignore moats in exchange for other things, like growth. It’s like in the Madden video games, if you want a player with speed, chances are you’re going to have to give up on some other attributes.

Zoom traded moats for speed. That trade works while they have the better product, but “superior product” is not one of the seven powers. Over time, product can be copied. When products hit parity, that’s when it’s important to have a moat in order to retain customers and pricing power. Imagine what will happen when Google makes Meet just as good as Zoom and decides to give it away for free.

Slack made the opposite trade. They gave up some speed, but they’ve built in network effects and switching costs.

Once a team has onboarded to Slack, it’s really hard to leave. Switching means rebuilding all of the channels and private groups that have developed over time to facilitate and speed up conversation and decision making. It likely means losing message history. And it means that the time employees have invested in learning Slack shortcuts will have to be spent learning a new tool. Typing “:thumbsup:” to return 👍🏻is so ingrained that I get frustrated every time it doesn’t work in iMessage.

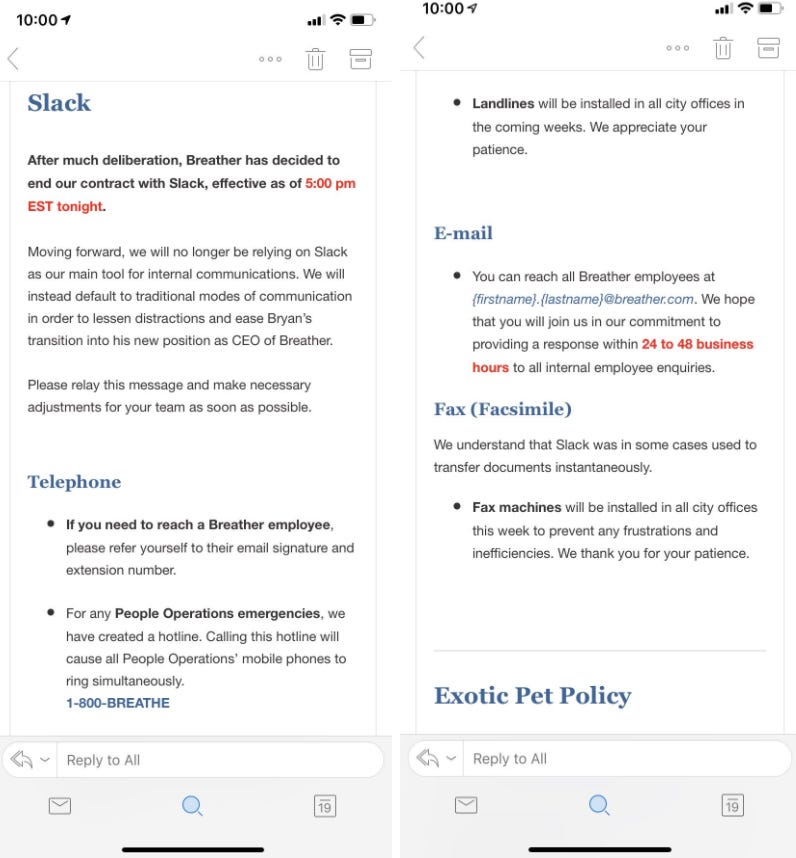

When I was at Breather, we were so addicted to Slack that the company April Fool’s joke last year was an announcement from our People team that we were transitioning off of Slack.

People FREAKED. Slack had become integral to the way we worked and communicated across ten markets. The idea of switching was so ludicrous that it became a company-wide joke.

Now, thousands of other companies (and growing everyday), are locked in, too. Zoom is one of many tools that allows companies to have meetings. Slack has become crucial infrastructure they rely on to keep the business moving. Right now, and for the foreseeable future, the cost of switching is too high for companies to contemplate.

Show Me the Numbers

A strategy is only useful insofar as it enables a company to generate outsized profits at some point.

To that end, the best thing I have ever read on Slack is the June 2019 2-parter that Wharton Professor Peter Fader and Emory professor Daniel McCarthy of Theta Equity wrote right before Slack went public. Fader and McCarthy applied their Customer-Based Corporate Valuation model to Slack to provide an estimated price target. If you’re a tech business geek, I highly recommend reading both Part I and Part II.

The posts knocked me over because they confirmed in numbers what I felt as a Slack user: once companies start using Slack, they very rarely leave. Fader and McCarthy inferred that only 10% of Slack customers churn within the first year, and that Slack retains a shocking 80% of its paying customers over 5 years. For comparison, according to Profitwell, the median monthly churn rate for SaaS businesses is 5-10%. Proportionally, most SaaS businesses lose as many customers in a month as Slack loses in a year.

Additionally, Slack also has Net Dollar Retention over 100%, coming in a little bit higher than Zoom at 143%.

Combined with its churn numbers, that means that of 100 customers who sign up for Slack, 80 still use Slack five years later, and those 80 pay 43% more each year than the initial 100 did in Year 1. When Slack signs up a customer, they can expect that it will still be around in five years, and will be paying them 4x as much.

This is network effects and switching costs in action. It’s also why I am so overwhelmingly bullish on Slack coming out of Coronavirus.

Of course, there are risks. Net dollar retention might decline as companies lay off employees and therefore reduce the number of paid seats. Microsoft might decide to give away Teams for free. Entire startups, Slack’s main customer base, will go out of business.

But Slack appears to be on pace to double, triple, or even quadruple the number of new paid accounts it would have expected in a usual quarter. The benefits will compound for years.

Fader and McCarthy gave Slack a $22-27 billion valuation target in June. Nearly one year later, it is trading at a $17 billion market cap. That’s a 23% discount to their low case. In the year since they wrote it, and particularly over the past three months, Slack has proven its ability to win big accounts, pulled years’ worth of revenue forward, and likely lowered acquisition costs and payback periods. Because of its network effects and high switching costs, Slack will continue to generate predictable revenue from these new customers, and grow with them as they rebound and star hiring again.

Even though Slack has nearly doubled since its’ ridiculous $17 per share low, I am still exuberantly bullish on the stock.

(This is not investment advice. You would be foolish to take investment advice from me. Etc.)

Bonus: F, Marry, Kill

Want an easy way to remember the difference between Slack and Zoom?

F, Marry, Kill, (but modified to fit my narrative 😜)

Zoom is attractive and easy, it’s the obvious choice for F.

Slack is a little harder to get, but once you get to know it, you realize it’s the kind of software you want to stick with forever. Marry Slack.

The big question for Zoom is: once this quarantine is over, will users kill it? If they want to, it’s as easy as canceling drinks.

Thanks for reading Hitched to Slack! If you enjoyed it, spread the knowledge by sharing it with a friend or co-worker. If you didn’t, reply and tell me why!

What’s Next?

🕰 Counting Time - May 21st, 6pm

Next Thursday evening, Not Boring is teaming up with one of my favorite people, Casper ter Kuile, the author of the upcoming The Power of Ritual, for a discussion about religious perspectives on counting time. We will be joined by Rev. Dr. Stephanie Paulsell, a professor at Harvard Divinity School, and Rabbi Emily Cohen, Rabbinic Resident at Lab/Shul.

Sign up to join the 150+ who already have here.

We have about a week to go before we close the Giant COVID Survey, the most wide-ranging COVID survey on the internet. Anja and I reallllllly want to get over 1,000 responses before we close it and we’re about 100 short. If you love knowledge, help us out by sharing the Giant COVID Survey in your group chats, on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn, or however you can!

𝟱 Le Cinq

I did an interview with my friend Sumeet Shah, a venture capitalist and author of Le Cinq. Each week, Sumeet asks 5 questions to an investor or operator to learn what they’re working on, what they’re interested in, and what products they’re obsessed with. My interview with Sumeet drops this Wednesday, subscribe now to get it first.

👟 Not Boring Thursday Edition - Kim and Kanye

Thursday’s Not Boring is going to feature a guest post by the wickedly talented, one and only Ali Montag. She submitted Kim and Kanye as her favorite Shotcaller and Worldbuilder, respectively, so of course we’re making her tell us more about that.

Nothing makes me happier than all of you sharing Not Boring. I spend a solid 15-20 hours a week writing this, and it has been really cool to see it start resonating enough that you’re willing to share with your friends, co-workers, and social media followers. And it’s working! There are 1,109 of us here now 🤯

If you know someone who is smart, curious, and loves nerding out on business strategy:

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Both Zoom and Slack are good. If Zoom is a video tool at its core, then Slack's heart is in messaging. If you're looking for a place to consistently communicate with the rest of your team, Slack can give you that. It offers everything from group messaging with message threading to one-on-one conversations.

Thanks