We Good Now?

A Dror Poleg x Not Boring Collaboration on WeWork as a Public Company

Welcome to the 997 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 41,668 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen here or on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Masterworks

Last week, you might have heard that the art market went—as they say in b-school—absolutely bonkers, setting a nice new record of $69 million for a nifty digital artwork. The takeaway? Art investing has hit the mainstream. But perhaps putting your money in physical art by the blue-chips makes more sense for you. Me, I own 5 paintings on Masterworks 👨🎨

Contemporary art has outperformed the S&P by 172% from 2000–2020, according to data from Masterworks. They were the first platform to let you invest in paintings by the likes of Basquiat, Kaws, and Haring. But what about returns? They’ve got that too: They sold their first Banksy work for a cool 32% annualized return to investors.

With results like that, it’s no wonder there are over 17,000 people on the waitlist. To skip the line, just use my special link, tell them the Packy sent you, and you’ll be good to go.

P.S. Here's some important legal info from Masterworks

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

Today’s essay is one that I’ve been waiting a long time to write: WeWork is going public.

I’m bringing in the big guns for this one: Dror Poleg. Dror literally wrote the book on the future of real estate -- Rethinking Real Estate. Dror’s writing combines history and future, and is brilliant, nuanced, and balanced, words that don’t often describe WeWork coverage.

We’ve waited years for this. We can’t wait any longer.

Let’s get to it.

We Good Now?

by Dror Poleg and Packy McCormick

If I told you about a company doing $3 billion in revenue, leading a multi-hundred-billion-dollar market, that offers the easiest way for Fortune 500 companies to do flexible work, counts Amazon, Microsoft, Walmart, Goldman Sachs, Spotify, Netflix, IBM, and Airbnb as customers, and is going public at a $9 billion enterprise value (EV), would you buy it?

What if I told you it’s burning $3.2 billion per year, has historically failed to meet nearly every target it set, and has to do construction every time it wants to increase its inventory? And that it had to pull a planned 2019 IPO due to investor disgust at the founder and CEO’s antics. Would you buy it then?

This is the WeWork enigma. It has done some truly mind-blowingly impressive things while burning mountains of Masa’s money. If it weren’t for some huge unforced errors, it would have gone public at a valuation near $50 billion way back in 2019, before COVID supersized remote work valuations. It rode a positive narrative to the moon, and came crashing down when the narrative flipped.

We all know We. The company’s story was everywhere in the fall of 2019. WeWork’s failed IPO was a car crash of epic proportions, and we all rubber necked. As someone who worked for a WeWork competitor, Breather, I watched it all with particular schadenfreude (this is Packy, speaking for myself).

But since its public failure, it installed new management, flew under the radar, and refocused on its core business. It’s less exciting, but more solid. Its business model is neither inherently terrible nor is it as high-margin, high-growth as a pure software business.

When WeWork was private, figuring out WeWork was SoftBank’s problem. We could afford to laugh at the company’s story without thinking too much about the actual business. But now that BowX SPAC’d it at a seemingly reasonable $9 billion valuation on $3 billion in revenue (in this economy?!), it’s worth taking a closer look. Today, we’ll do that:

The Royal We. Adam Neumann was narcissistic and brash… exactly what was needed to shake up office real estate.

WeStory. From 3,000 sq ft in Soho to millions across the world, fueled by an epic hype flywheel.

From WeWork to We. Neumann pushed the company outside of office and into a little bit of everything.

IPOh No! WeWork’s attempted 2019 IPO failed spectacularly thanks to unforced errors, and the company brought in new management, refocused, and trimmed down.

WeSPAC. On Friday,Vivek Ranadivé’s BowX SPAC announced that it’s taking WeWork public at a $9 billion valuation.

Side Note: Masa is a Genius Again. Masa is on a tear. WeWork breaking even would be the icing on his comeback cake.

WeWork by the Numbers. The refocused WeWork is a straightforward business.

The WeWork Bear Case. This time, maybe it’s the market’s fault.

The WeWork Bull Case. WeWork survived, erased its mistakes, and is perfectly positioned to capture value in a more flexible world.

Back to the Future. You know who would have been a perfect CEO for this market?

Look, no one expected us to be publicly defending Adam Neumann less than we, but here we are.

The Royal We

Maybe Adam Neumann really was the savior Adam Neumann thought Adam Neumann was.

For the first eight years of WeWork’s life, the We Story was the Adam Neumann story. The two were inextricably linked. He was the Royal We.

The WeWork co-founder and ex-CEO was a narcissistic cult leader who made off with billions and left employees and investors holding the bag.

He regularly called his direct reports’ direct reports into late-night meetings to publicly embarrass their bosses.

He pushed his co-founder, Miguel McKelvey, aside to give his wife Rebekah more power.

He personally trademarked “We” and sold it back to his own company for $6 million.

He established what is quite possibly the dumbest fucking financial metric in financial metric history: Community Adjusted EBITDA.

He set delusional goals for himself: “becoming leader of the world, living forever, amassing more than $1 trillion in wealth.”

But Adam Neumann was also the perfect person to launch WeWork, shake up the sleepy commercial real estate industry, and change the way that people rent office space.

Commercial real estate isn’t like software, a fact that critics pointed out over and over again as WeWork’s valuation soared to $47 billion. In the world of bits, a polite, meek coder can spend months locked away in a dark room, emerge with a brilliant piece of software, put it up for sale on a website that anyone can access, and let the market decide whether what they built is worth paying for. It’s pretty close to a meritocracy.

Commercial real estate is an oligopoly. A handful of families, companies, and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) own the vast majority of the desirable real estate in the world’s major metropolises. They own buildings and collect rent checks. Life is pretty good if you own the right piece of real estate, so landlords are not known for being particularly forward thinking or open to change. Polite and meek don’t work in real estate.

Adam Neumann almost sunk his company, but he was also the right person, in the right place, at the right time to get it off the ground in the first place.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to say that WeWork should have done all of the good stuff and none of the bad stuff. They should have done revenue share deals with landlords instead of taking on lease obligations. They shouldn’t have thrown big parties. Adam should have been more straightforward and honest.

But you can’t have your cake and eat it too. A quieter, more conservative WeWork wouldn’t have had the scale, money, shine, or leverage to make a dent in commercial real estate.

WeWork was the disruptor. Like Napster, it broke some rules. Normally, the disruptor makes a lot of noise, spends a lot of money, and fails. Someone else swoops into a shaken industry, works with landlords, and builds a solid business.

But in this story, Adam met Masa. SoftBank’s billions both choked WeWork and kept it alive. Adam got the boot, and rightly so. His company, under new management, lives to fight another day.

What’s unique about this story is that WeWork is both Napster and Spotify. It’s disruptor and partner, destroyer and builder. Somehow, eleven years into the WeWork journey, after a failed IPO attempt and turbulent ups and downs that would make Kingda Ka jealous, WeWork is going public. It’s in the best position to capture the value created by the destruction it wrought.

But it all started with 3,000 square feet in Soho.

WeStory

Just as mobile boomed, the financial markets crashed, and people began working over WiFi on laptops, Neumann and McKelvey launched GreenDesk, an environmentally-conscious co-working space, in Brooklyn’s Dumbo neighborhood in 2008. They quickly realized that green wasn’t the draw, community was, so they sold GreenDesk and launched WeWork in 2010 with 3,000 square feet at 154 Grand Street in Soho. Coincidentally, Packy got coffee at Gasoline Alley in that building every day when Breather’s office was down the street.

WeWork wasn’t the first coworking space -- that honor goes to the aptly-named Coworking Space, launched in 2005 in SF -- but it was the loudest and most ambitious. It took Neumann’s special blend of confidence, salesmanship, capital-raising ability, and casual relationship with the truth to force an otherwise unmovable industry to fundamentally change.

When WeWork started, there were a few thousand square feet of coworking space in the world, but the combustible cocktail of Neumann and venture capital changed that quickly. WeWork raised a humble $1 million Seed in October 2011 and another $6.9 million that December, and in April 2012, Benchmark came in to lead a $17 million Series A. It quietly raised another $190 million in 2013, before lifting the veil and announcing a massive $355 million Series D at a nearly $5 billion valuation in October 2014 led by major institutional investors Goldman Sachs, Wellington Management, and T. Rowe Price.

Those investors’ involvement sent a clear signal that WeWork wanted to go public, and that the public markets were waiting with open arms. At the time, institutional investors rarely backed private companies. Instead, T. Rowe, Goldman, and Wellington and other large institutions received allocations in the Initial Public Offering (IPO), and their purchases supported companies’ ability to smoothly enter the public markets. If those IPO experts were in, the logic went, they must believe that WeWork had a good shot as a public company.

In reality, what it meant is that Adam Neumann’s skills as a salesman extended beyond just local landlords and VCs. He was able to convince some of the world’s most buttoned-up investors that WeWork wasn’t just any real estate company. That, in turn, convinced landlords to lease WeWork more space, which meant more revenue, which got investors excited, which got landlords excited, and so on. Neumann built a Hype Flywheel so strong that it sucked in people typically immune to hype, including Jamie Dimon and WeWork’s board.

In just four years, WeWork transformed coworking from a quaint, communal way to work into something on every landlord’s mind. At the time of the Series D announcement, just four years into its life, WeWork was generating $150 million in revenue at 30% operating margins, and had accumulated over 1.5 million square feet of leases. Over the next three years, it would add roughly 6.5 million square feet in the US alone, while going international and launching subsidiaries in China and Japan.

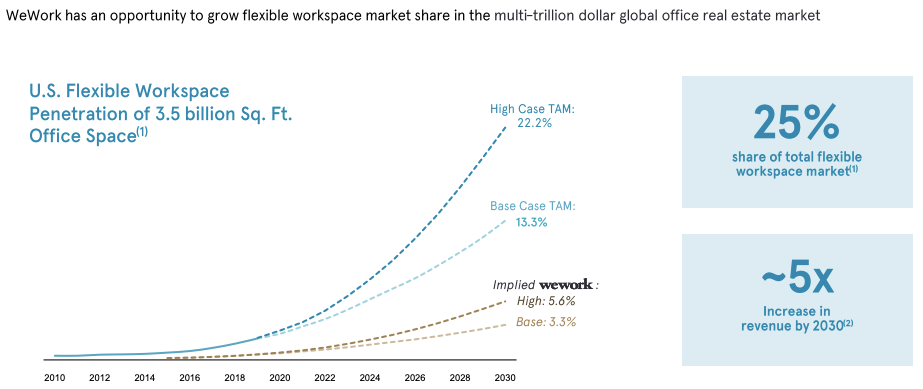

Source: Vox

Today, about 4% of the 3.5 billion square feet of office space in the country are flexible. By 2030, that number will be several times higher. The trend towards more flexibility in office rental is inevitable: flexible office reduces friction, lowers upfront costs, and shortens commitment lengths. It lets office experts do what they do best, and lets companies focus on the things that they do best. It does to office what SaaS and the cloud did to software, and gives employees a say in where they work. It transforms office expectations from B2B to consumer.

That transformation would not have happened nearly as quickly without Adam Neumann. If that were the whole story -- WeWork uses capital, aggression, and force of personality to transform massive, sleepy industry -- the company would have gone public years ago, and Neumann would be a venerated public company CEO.

But there were clues in the deck the company used to raise that $355 million Series D that it didn’t want to just rent desks. It wanted to change the way WeLive and “elevate the world’s consciousness.” And in 2017, Neumann found his soulmate, and with him, the pools of money he’d need to rule the world.

From WeWork to We

When he met McKelvey, Adam Neumann had run two failed companies: one that made a collapsible heel for women’s shoes, another that made baby clothing with knee pads. Both seem like Shark Tank pitches that would have gotten five “I’m outs.”

In half a decade, though, Neumann had built the largest coworking company in the world, thrown the traditional five-to-ten-year lease model into question, and raised over $1 billion dollars. His company controlled millions of square feet of office. Given that meteoric rise, it’s understandable that Neumann thought he could do anything.

It started with WeLive. If coworking worked, why couldn’t coliving? Theoretically, the same principles apply: lease space wholesale, chop it up and add shared amenities, and sell it retail. Plus, maybe if we all lived together, we could cure loneliness and make people happier. In the company’s Series D deck, it said, “The demand for Space as a Service extends to residential real estate, making WeLive a natural extension of the WeWork concept, community, and brand.”

Series D investors bought it, as did investors in the company’s $433 million May 2015 Series E and its $690 million November 2016 Series F. But no one bought Neumann’s vision to be more than just office space more than his Series G lead: Softbank’s Masa Son.

When Adam met Masa in December 2016, the SoftBank CEO showed up two hours late, told Neumann he had 12 minutes for a tour, and suggested they continue the conversation in the car. There, after knowing each other for 28 minutes, Son famously whipped out an iPad, drew up terms for a $4.4 billion investment, and asked Neumann to sign. He did.

Masa, according to Neumann, appreciated that he was crazy, but thought that he needed to get crazier. Oh, he did.

In the two and a half years between closing that investment and filing to go public, in addition to accelerating the expansion of its core business, WeWork:

Invested in a wave pool company, WaveGarden

Opened its first gym/spa, Rise by We, in New York

Launched a grade school for young entrepreneurs, WeGrow, under the leadership of Adam’s wife, Rebekah

Acquired coding boot camp Flatiron School

Acquired Meetup for $200 million

Acquired MissionU, a one-year vocational bootcamp, under the WeGrow brand

Acquired Teem, a facility management software company, for $100 million

Raised another $3 billion from SoftBank

Legally changes its name to The We Company, as part of Neumann’s expanded vision "to encompass all aspects of people's lives, in both physical and digital worlds"

Updated the company’s mission to “elevate the world’s consciousness.”

Nearly sold over half the company to SoftBank for $16 billion before SoftBank pulled out and invested $2 billion at a $47 billion valuation

Acquired office management platform Managed by Q for $249 million

Acquired Islands, Prolific, and Waltz in one week

Acquired workspace management software Space IQ

Acquired Spacious, which built ground-level drop-in workspaces

By the time it filed its S-1 to go public on August 14, 2019, Neumann’s company had transformed from WeWork, a coworking company, to The We Company, which did a little bit of everything. That’s when things started to fall apart.

IPOh No!

What is inside all of us but greater than each of us? According to The We Company’s IPO filings, the answer is “the energy of We.” The company dedicated its first formal communication with public market investors to... itself.

Investors were already concerned that WeWork was, at worse, a cult or, at best, a company run with little consideration for objective reality. In the months leading to the IPO, the narrative around the company turned dark. A series of bombshell reports by WSJ’s Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell raised multiple red flags. These reports included:

Adam Neumann cashing out $700 million of his shares in the company, using some of that money to buy real estate, and leasing some of that real estate back to the company;

Allegations about gender and age discriminations;

Concerns about management’s lack of focus amid mounting losses;

SoftBank scrapping plans to acquire a majority stake in WeWork for $16 billion; and

A discrepancy between the valuation Softbank used for its last direct investment in WeWork ($47 billion) and the valuation the company used to buy shares from existing WeWork employees and shareholders ($23 billion).

The S-1 provided an opportunity to cut through the noise and focus everyone’s attention on the company’s actual business. The We Company passed on the opportunity. The S-1 highlighted the company’s quirks, confirmed media reports about lack of executive judgment, and made it difficult for anyone serious to continue to defend We and its valuation.

Less than three weeks after the S-1 was published, the Journal reported that The We Company was considering slashing its target valuation by “more than half.” The company was facing “widespread skepticism over its business model and corporate governance.” Public markets seemed to be losing their appetite for money-losing unicorns. Uber and Lyft, which went public earlier that year, were trading below their IPO price. But those other companies at least managed to get some people excited. As one analyst put it, “there were Uber bulls, there were Lyft bulls,” but he heard no bullish views at all about the flexible office giant. “WeWork,” he said, “is exhausting people’s cynicism.”

But cutting the valuation was no longer enough. Investors lost confidence in the company and its CEO. On September 17, 2019, The We Company decided to postpone the IPO indefinitely. A week later, Adam Neumann stepped down as CEO and ceded his control of the company. But he managed to let the door hit the company on his way out. The ex-CEO was set to receive up to $1.7B in share buyouts, consulting fees, and a structured loan.

We’s failed IPO was the most spectacular collapse in business history. Within weeks, it went from being one of the world’s hottest companies to the verge of shutting down completely. Many say the collapse was inevitable. They see the company’s reliance on long leases with suppliers (landlords) and short commitments from customers as a recipe for guaranteed disaster. Instead, WeWork should have either bought the buildings or signed revenue-sharing agreements with landlords instead of committing to pay rent.

These explanations make sense, but do not explain WeWork’s collapse. Most companies on earth sign long leases and rely on short-term commitments from customers. This includes retailers, restaurants, tech companies, and even some profitable coworking and hotel operators. It would have been great for WeWork to own the buildings or partner with landlords, but I don’t think Neumann could have finessed an average mortgage broker as well as he finessed some of the world’s leading venture investors. And convincing landlords to share the risk when they can simply collect rent is a tall order: it’s possible, but it would have taken ages, leaving WeWork a small and unknown operator among hundreds of others.

Yes, WeWork could have signed better leases, it could have been more discerning in its expansion decisions, and yes, it could have occasionally partnered with landlords and investors to operate or acquire buildings without signing any leases. There was nothing inevitable in its collapse.

What ultimately killed The We Company’s IPO was the shift in narrative. A series of unforced errors by Neumann made him look like a cynical, greedy nepotist who did not believe in his own company — selling shares ahead of the IPO, leasing his own buildings to the company, appointing his wife as Co-Founder and various other relatives and buddies as executives, and charging his own company millions for the right to use the name that he chose for that same company. Once all these stories came out, WeWork could not have taken any company public, let alone one that requires some selling.

In the weeks following the failed IPO, The We Company did everything it should have done before the IPO. It started to renegotiate leases across the world, realigning its growth around proven locations. It shut down or spun off non-core business units and acquisitions, including WeGrow, Managed by Q, and Meetup. It started shedding employees. And it appointed a CEO that could not lead a cult even if he wanted to — Sandeep Mathrani, an experienced real estate operator who is respected by many of the world’s largest landlords and institutional investors.

Mathrani’s appointment was announced on February 2, 2020. That same day, the 9th Covid-19 patient was diagnosed in the United States. A month later, some of the world’s largest tech companies advised most of their employees not to come to the office. Within a few more weeks, most developed countries were under lockdown and office buildings were deserted.

A global pandemic was a good starting point for the new CEO. He capitalized on landlord distress to renegotiate leases and walk away from deals that had not been finalized. He sold a majority stake in WeWork’s China joint-venture to investors who were happy to expand in one of the few countries where people were already back in offices. He avoided a lot of the flack for mass layoffs thanks to similar layoffs happening across the economy — and the cushion provided by the U.S. government’s expanded unemployment benefits and stimulus checks. He focused the company’s offering around larger, corporate customers. And he even changed the company’s name back to WeWork, erasing Neumann’s all-encompassing We Company.

Meanwhile, WeWork’s shareholders poured more money into the company, showing their commitment to its success. And they renegotiated Mr. Neumann’s golden parachute, saving some money for the actual business and indicating to the public that lessons have been learned.

Ultimately, the pandemic stress tested WeWork’s business and set it up to become a public company.

WeSPAC

To recap, WeWork burned $15 billion dollars, pulled an IPO, faced a pandemic that prevented people from going to the office, and lived to tell the tale.

On Friday, BowX Acquisition Corp, a SPAC led by “Mr. Realtime” himself, Sacramento Kings owner Vivek Ranadivé, announced that it’s merging with WeWork to take it public at a $9 billion enterprise value.

The deal, which has been rumored for a while (we discussed it on a podcast when the rumors began swirling in January), actually makes a ton of sense. WeWork is the proto-SPAC.

Thus far, the SPAC structure has mostly been used by companies like WeWork: companies with big potential, but some hair on them. For WeWork, the hair is its bumpy history combined with the fact that it lost $3.2 billion last year. (Don’t worry, like most SPACs, it predicts that it will double revenue and turn very profitable by 2024.)

In exchange for dealing with that hair, SPAC sponsors (the people who launch, and lend their credibility to, the SPAC) receive a little extra ownership in the company, in the form of warrants. They also stand to benefit if the price of their shares rise over $10 after the deal closes. To do that (recent market craziness aside), and for the investors who bought the SPAC’s shares to make money, the two sides need to agree on a price that has some room to run.

In WeWork’s case, BowX and WeWork agreed to an EV of $8.966 billion.

Since the price is negotiated and not dictated by the market, the big question for SPACs is whether the market agrees with the price. If they don’t, the SPAC will trade down and shareholders can vote down the deal. If it does, the shares will trade higher than $10. This year, 74% of closed SPACs have traded up.

That question is particularly fascinating in WeWork’s case because of its private market funding history. Most startups have different investors lead, and therefore price, each round. But SoftBank is the only fund that has priced WeWork since 2017. With the SPAC, it once again negotiated terms with just one investor. But now, the market can finally weigh in.

So far, it’s weighing in in favor of the deal. Upon announcement, the shares traded up to $11.71 before closing at $11.21 during after hours trading on Friday. That means the market is currently valuing WeWork at just over $10 billion.

That’s a massive drop from where WeWork expected to go public just two years ago, but it’s also a huge relief for investors who pulled the company from the brink of bankruptcy. No investor had more skin in the game, or is breathing a bigger sigh of relief, than Masa.

Side Note: Masa is a Genius Again

We just need to pause here for a second and marvel at WeWork sugar daddy and SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son. As of last summer, investors had written him off as a cautionary tale of what goes wrong when one man has too much hubris and too much money (sound familiar?).

Dror has been a Masa believer all along. In September, Packy wrote Masa Madness. He set out to rip Masa and SoftBank apart for big, losing bets like WeWork and YOLO options trades that moved the market, but came away begrudgingly impressed. Since then, Masa has been on a heater.

In September, SoftBank sold chip maker ARM, which it acquired for $31 billion in 2016, to NVIDIA for $40 billion. Not spectacular, but a win.

When DoorDash went public in December, SoftBank turned its $680 million investment into an $11.9 billion payday.

Coupang outdid DoorDash when the Korean ecommerce giant went public in March and gave SoftBank a $33 billion profit on its $3 billion investment.

It’s not all up and to the right -- SoftBank-back Greensill filed for bankruptcy the same week Coupang IPO’d, costing the Vision Fund $1.5 billion -- but even though the Vision Fund is a very, very big venture capital fund, it’s still a venture capital fund. It will be defined by some big losers and some massive winners.

On paper, Coupang is the Vision Fund’s biggest winner and Alibaba is Masa’s best investment of all-time. But if WeWork somehow breaks even, after Masa very publicly poured $13.5 billion into the company and wrote it down to less than $2 billion, and after being relentlessly mocked for the investment, it will be the biggest moral victory of Masa’s career.

SoftBank owns roughly half of WeWork after averaging down on the near-IPO-crash. On paper, Masa’s already more than doubled the value of his post-writedown WeWork holdings. If the company gets to a roughly $30 billion valuation, he makes his money back, and no one will ever question the Masa magic again.

So will he? Let’s dive into WeWork’s numbers.

WeWork by the Numbers

Now that WeWork’s model has been stripped down to the core, it’s actually quite simple: The company enables companies to access workspaces of all shapes and sizes, anytime, anywhere. As Dror pointed out in his book:

“The office of the future is not a single location; it is a network of spaces and services. The network must include spaces designed for the performance of specific tasks such as focused work, team brainstorming, client presentations, employee training, meetings, and more.

Tenants don’t want “space”; they want a productivity solution to help them attract and retain the best individuals—and empower those individuals to produce their best work. The solution should include physical spaces, various services, and digital tools that enable companies and individuals to make the best use of their time. At its best, it should also empower individuals to lead healthy and meaningful lives.”

WeWork is the only company that offers this “office of the future” on a global scale. Companies such as Industrious and The Office Group have a great product but do not have a global footprint. IWG has a global footprint, but it does not deliver a consistent experience, does not have a consumer brand, and it’s offering is not tied together by easy-to-use software. This does not mean WeWork is a “software company”; it means WeWork uses and sometimes develops software better than its competitors. The same could be said of Starbucks, Dominos Pizza, or CitizenM hotels.

WeWork brought in $3.2 billion in revenue in 2020, which is the same as its revenue for 2019 and its projected revenue for 2021. The bulk of revenue ($2.9b) was generated by WeWork’s Core Leased business. These are spaces that WeWork leases from landlords and resells to its own members. There are now over a million WeWork workstations in 850 locations across 150 cities. These workstations are paid for by WeWork’s 450,000 “Physical Memberships,” payments for ongoing access to a specific location.

Contrary to popular belief, most WeWork members are not freelancers and small startups who commit month-to-month. More than 50% of physical memberships are from companies with 500 or more employees, more than 50% of memberships are committed for 12 or more months, and only 10% or so of memberships are month-to-month.

But while WeWork is more stable, it still loses plenty of money. Net income for 2020 was negative $3.2 billion, and adjusted EBITDA was negative $1.8 billion (excluding the China JV which has since been spun off).

Generating $3.2 billion during the worst year in office history is quite a feat. WeWork’s losses are also impressive — in absolute terms, but also relative to the market as a whole. The company did better than most people expected. It was expected to get completely crushed during a Covid-like crisis, losing customers while still having to pay suppliers. And yet, many WeWork customers kept paying — even if reluctantly — and WeWork itself managed to use the crisis to reduce its own obligations to landlords.

The company projects 6% revenue growth in 2021 and 47% in 2022 once the office market returns to a semblance of normalcy. By 2024, WeWork expects to bring in nearly $7 billion in revenue. These projections are ambitious, but they are not crazy. A company that sold $3.2 billion of office space in 2020 can sell twice as that four years later, assuming the office market still exists.

The big question is whether WeWork could ever generate a profit. To do so, it will have to reduce and/or find new ways to finance the cost of launching and refurbishing its spaces. It sure is trying: WeWork significantly slowed down its expansion in 2020 which led to a 60% reduction in capital expenses. The company plans to cut CapEx by an additional 75% in 2021.

Slowing down expansion will increase the share of mature locations in the company’s portfolio. If 2019 is any indication, mature locations in the company’s 20 best markets generate a “Building Margin” of 27%. Building Margin is revenue minus rent and other building expenses (but not amortization or depreciation). This non-GAAP metric is optimized to show WeWork’s business in the best possible light. And just like WeWork’s original S-1, the latest filings do not tell us how often WeWork would need to refurbish its locations and at what cost (most mature locations have been open for less than 36 months).

Occupancy across WeWork’s portfolio was 47% in 2020, down from 72% in 2019. This, too, is not good in itself but better than expected at a time when most people are essentially barred from going to the office. The company says it can achieve EBITDA breakeven at 70% occupancy, and projects 75% occupancy in 2021, 90% in 2022, and 95% in 2024. These, too, are ambitious projections. But WeWork did consolidate its portfolio around better-performing locations, so it’s not unreasonable to expect higher occupancy once people return to the office. However, 95% sounds too high. Even if all goes well, the structural vacancy for a flexible office business is likely higher, especially if the company plans to keep growing (and it is).

Still, we believe WeWork can turn a profit on its core business if it can avoid Neumann-era reckless expansion and spending. And WeWork’s other business lines can also help reduce vacancy and improve margins. These businesses include WeWork All Access, Marketplace, and Platform.

The most interesting business line is WeWork All Access (WAA): A monthly subscription that provides on-demand access to (some of) WeWork’s global network of locations. Think of it as “Spotify for Office Space”: Users or their employers pay a fixed monthly fee of $299 and can access hundreds of shared locations. The service also allows them to book private workspaces and meeting rooms for additional fees.

Beyond the benefits for customers, WeWork hopes that WAA would enable it to monetize underutilized spaces across its portfolio. WAA revenue is expected to have much higher margins as it relies on spaces that are already built and operated for the company’s core business. On-demand access is also a gateway to other WeWork services and allows companies to try out different locations and workstyles before committing to a long-term deal.

WeWork All Access launched in 2020 so there is no historical revenue to look at. The company expects it to generate $90 million in revenue in its first year (2.8% of WeWork’s total). At $299/month, this boils down to 25,000 paying customers or less than 1% of WeWork’s existing member base.

As Breather alumni, we can’t help but love the idea of on-demand office space. We also understand that this can hardly be a standalone business. But it could work well as a complement to WeWork’s existing business. This product is ahead of its time — most companies would still like their employees to be somewhere rather than anywhere. But we expect it to appeal to some of the world’s forward-thinking and fastest-growing companies. WeWork might have to tweak the offering and pricing, but this can become a significant business over time.

WeWork’s other two business lines are Marketplace and WeWork Platform. Marketplace is a collection of value-added services the company offers its members, usually in partnership with other vendors. These include add-ons such as dedicated internet networks, HR and payroll services, and (soon) insurance. Marketplace generated $37 million in 2020 and is expected to reach $86 million in 2021 and $313 million in 2024. We cannot say that we understand the basis for these predictions, particularly the jump from 2020 to 2021. Marketplace is tangential as a source of revenue, but it has higher profit margins and it can contribute to lower customer churn. Still, the company has been touting the Marketplace opportunity for several years and so far it has failed to become a significant business.

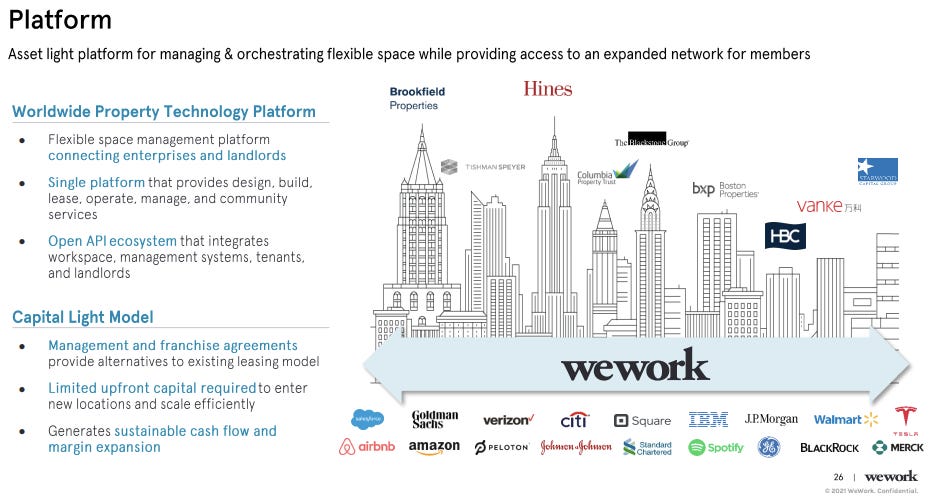

The last business line is Platform, where WeWork partners with landlords to design, fit out, and operate spaces that it does not lease. In these scenarios, WeWork signs a management or franchise agreement with landlords and gets a share of the revenue generated by the spaces it operates. Landlords, in turn, provide the space and cover most of the fit out costs.

Platform sounds like an ideal strategy — exactly the type of strategy pundits thought WeWork should have pursued instead of signing leases. Indeed, it offers higher margins and lower risk. But so far, it has not proven to be a business that can grow quickly. WeWork generated $5 million in Platform revenue in 2019, $5 million in 2020, and is expecting it to reach $12 million and $159 in 2021 and 2024, respectively.

These projections represent a big jump. They are ambitious but not unreasonable. Post-COVID, many landlords would be much more amenable to partnering with operators like WeWork to upgrade their inventory and tie into a network of additional spaces and services. But as we mention below, this would only work in WeWork’s favor if landlords are in just enough distress to make them partner, but not enough distress to crash the whole office market.

The WeWork Bear Case

In 2021, many of the original concerns about WeWork have been turned on their head:

Back then, most people were skeptical that most office tenants would be interested in more flexibility and services. Today, the bigger question is how many companies will use offices at all and whether additional services would be enough to lure back employees.

In 2019, the concern was that landlords were too complacent to partner with WeWork and strong enough to force it to pay high rents for years to come. In 2021, the bigger concern is that landlords have too much vacancy and are eager to partner with anyone who can help them attract tenants.

In 2019, the biggest risk was that capital markets would dry up and WeWork would not be able to continue to fund its losses. While this is still a concern, the bigger risk in 2021 is that capital markets would fund other companies that will expand aggressively and poach WeWork customers (and executives).

In 2019, the office market and even the stock market seemed to behave normally and the main concern was that WeWork itself would do something crazy. In 2021, it is the markets that are crazy and WeWork is the one that seems to have a reasonable plan and a real — if still fragile — business.

In 2021, the two biggest risks for WeWork are market risks. In the office market, the company is walking a tightrope. It benefits from the relative distress among office landlords and from the uncertainty about the future among office tenants. But WeWork is not just an alternative to the office market; it is also a major player within it. If too many companies decide to give up a big chunk of their office spaces, WeWork would suffer. Landlords could also decide to convert big chunks of their portfolio into WeWork-like spaces without partnering with WeWork. In that scenario, WeWork would still have an unparalleled offering, but an abundance of supply could eat into its margins.

In financial markets, WeWork is relying on investors to maintain their appetite for stocks and SPACs in general, and for companies trying to transform giant, heavy industries in particular. If the market collapses or even softens, WeWork is not likely to be among a handful of stocks that buck the trend. And if some SPACs are ensnared in scandals, all SPACs are likely to suffer.

Ultimately, WeWork’s main weakness in 2021 is its inability to control the public narrative. The companies that do best in the current market are those that have charismatic CEOs, who make outrageous statements and can skip traditional middlemen and communicate directly with the public. We’re thinking Elon Musk, Richard Branson, Cathie Wood, Chamath Palihapitiya. It also brings to mind what’s-his-name... that guy who wanted to be president of the universe. We’ll return to him later.

But first, let’s consider the bull case for WeWork.

The WeWork Bull Case

If you had told me In the fall of 2019 that I’d ever utter the words, “Here’s my bull case for WeWork,” I would have thought my kid wished that I could only tell lies.

But that was at a $47 billion valuation, with Adam Neumann at the helm. Today, leaner, saner, and more focused, with tailwinds at its back, WeWork is valued at $10 billion. Back then, Airbnb was worth 75% as much as WeWork; two years later, it’s worth 10x as much.

The thing about being the disruptor is that it gives you a big head start if you can survive. Thanks to Masa, WeWork lives. It has tens of millions of square feet of hard-to-build inventory, office management and access technology that it burned billions to build, unparalleled design and construction muscle for the scale and speed at which it operates, an enviable client roster, and more accumulated assets. All of that cost a ton of money in the past, which doesn’t matter to new investors: they get it all for the low, low price of $9-10 billion.

PLUS, COVID gave WeWork a magic eraser on some of its more permanent mistakes. It renegotiated or exited bad leases and right-sized the team. If you’re investing in WeWork today, you get to look forward, not back. How attractive “forward” looks depends on improvements in two areas.

All the shenanigans aside, Adam’s WeWork consistently overpromised and underdelivered in two key areas: profitability projections and asset light expansion. In the SPAC presentation, Sandeep’s WeWork is making similar promises.

Profitability Projections. WeWork expects to generate positive Adjusted EBITDA by Q4 this year, and projects 11% EBITDA margins for 2022.

Easy to put in a deck, harder to do. The company has a long history of dramatically missing its profitability projections, as the Wall Street Journal pointed out in 2019:

While Mathrani won’t control the narrative with his words like Neumann did, if WeWork actually hits its target and turns a small profit in Q4 this year, that action would speak louder than words.

Capital Light Expansion. The holy grail in flexible real estate has always been capital light expansion, or signing revenue share deals with landlords instead of leases. Everybody says they’re going to be capital light -- WeWork said it, Knotel said it, Breather said it -- and we all genuinely wanted to, but it’s tough to pull off. If they were open to it at all, landlords really only wanted to do revenue shares on the spaces they had the hardest time leasing, aka the worst space in their portfolio.

COVID may have actually made landlords more willing to play ball. WeWork has gotten out of some bad leases, and renegotiated others into management agreements in which the landlord pays WeWork for its branding, technology, marketing, and operations, and shares some of the upside when they bring in a tenant. WeWork highlights this “Platform” model in the SPAC deck:

Landlords have office space that they want to offer flexibly, big companies want to access office space flexibly, and WeWork sits in the middle and takes a small cut.

WeWork, to feed the narrative needed to hit its multiples, mentioned technology 92 times in its 2019 S-1; in the SPAC presentation, they highlight what technology might directly enable. The Platform approach, along with WeWork’s All Access pass, mean that the company could have the best of both worlds: a focus on its core product, office space, without tying its fate directly to the number of square feet it leases. That should be a boon for both margins and growth potential.

If WeWork can prove that it can be profitable, and that it can continue to grow while lowering, but not eliminating, its dependence on leases (there are good deals to be had out there), it’s back at the head of the push to make office space more flexible and easy to access.

If it can handle the basics, WeWork becomes a bet that office space, like everything else, will adapt to meet modern consumer expectations, and that the companies that remove friction will win. That’s a narrative the market can get behind. Opendoor, despite owning houses and missing its numbers due to the pandemic, is trading 120% above its acquisition price. Opendoor has more competition and a much smaller market share in the residential real estate market than WeWork does in office.

If the company can be believed (and that’s always the question with WeWork), it will control one out of every 20 square feet of office real estate in the country by the end of the decade, plus hundreds of millions more around the globe.

In the bull case, WeWork finally captures the value that it’s shaken loose. It benefits from a head-start it was lucky to survive, and flexes its muscle as the one company landlords and enterprise clients can trust to deliver well-designed flexibility anywhere in the world at an affordable price. It continues to do what it’s always done -- grow really quickly -- but it does so with a real focus on unit economics.

For all the questionable things Adam Neumann did, his company, in under a decade, transformed office real estate from a stodgy B2B product into a user-centric consumer product. As work becomes more flexible, and employees have a say in where they work, WeWork is best positioned to capture new demand at scale.

Maybe nothing speaks to WeWork’s upside better than Miami. WeWork’s initial weak performance in Miami was an open industry secret; now, WeWork is the official flexible office partner of the city to which half of the tech industry seems to be moving.

Viva WeWork.

Back to the Future

When you’re living through something, it always feels unique. With the benefit of hindsight, though, things tend to follow predictable patterns. While the details may change from case to case, the Gartner Hype Cycle plays out over and over again with new products.

While WeWork isn’t likely to elevate the world’s consciousness anytime soon, it can rent office space to companies big and small more flexibly, better designed, and at a lower price than would have been possible a decade ago. That’s pretty good.

But the market today is largely fueled by narratives. Tesla is a story about a clean, sustainable future. Bitcoin is a story about money without middlemen. Heck, even Gamestop was a story about… something, told by a charismatic youngster with long hair and funny t-shirts.

You know who would have been perfect for this market? Adam Neumann.

In 2019, Neumann ran into a public market buzzsaw that was not friendly to the kind of antics that private market investors sometimes let companies get away with. Today though? Today, public market investors have been eating that shit up. Want proof? Look no further than Nikola and its $5.5 billion market cap despite no business beyond a video of a truck rolling down a hill.

We’re not suggesting that Neumann take back the reins — over the long term, Mathrani’s approach of actually building a strong business will win out — but WeWork would be well-served to borrow some of its founders positive attributes. While Neumann was certainly off on the execution, he was right that people want to feel like they’re part of something bigger than themselves.

Even an office space can make its occupants feel something, and even an office space company can make investors feel like they’re part of a movement. The future of office is definitely Not Boring. If WeWork needs help telling its story, you know where to find us: working from anywhere we want.

Thanks to Dror for teaming up, and to Dan for editing!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Thursday,

Packy

How does Benchmark end up? The SoftBank deal took Adam Neumann out, but not one word has appeared in the media about the other owners of the new WeWork.

The analysis on market size of flexible workspace is on-point. However, I wonder the rise of hybrid office will affect the market, bearing in mind 'We are Never Going Back'?