Together, More Bull, More Bear, More Fun

Pinduoduo: A Chinese Characteristics x Not Boring Collab

Welcome to the 2,932 newly Not Boring people 🤯 who have joined us since last Monday! Join 64,437 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts (soon)

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Write of Passage

I’ve never made a higher-ROI investment than Write of Passage. It’s not even close.

Back in April 2019, I was bored at work, my brain was atrophying, and I was at best a passive participant in the Great Online Game. Then I saw a tweet from David Perell about a course he was running, Write of Passage. I loved writing and I was bored, so I decided to take a flyer.

Two years later, I can trace every good thing that’s happened to me professionally -- this newsletter, Not Boring Capital, friendships with great people -- back to that course. Over the next couple of weeks, I’m going to go in-depth on my writing journey, leading up to a live workshop with David on August 11th. Over 4 short essays, I’ll tell you about:

How to start writing online, even if you think you have nothing to write about.

The messy process I use to write way too many words every week.

How to build your Personal Monopoly and attract serendipity online… in other words, how to get involved in the Great Online Game.

I can’t recommend the course highly enough… but I’ll try. Sign up here to receive four emails from me and learn what writing online can do for you.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday! We’re back with China Tech Bull & Bear.

Back in January, I wrote a piece about Alibaba. Lillian Li, whose writing on Chinese tech I’d read and respected, but who I’d never met, DUNKED on it on Twitter.

She said that “the piece missed local context.” Which was fair. Among other points, she also pointed out that Pinduoduo was a threat to Alibaba.

Lillian and I got to know each other after that exchange and decided to team up on a bull & bear piece about Agora, which we published in April. Now, we’re going right back to where it started in that original thread: Pinduoduo.

When it comes to China tech, Lillian is one of a small handful of people I turn to. She writes a great newsletter called Chinese Characteristics. You should subscribe if you’re interested in China tech, and you should be interested in China tech:

Let’s get to it.

Pinduoduo: Together, More Bull, More Bear, More Fun

The Summer of 2020 was the Summer of Pinduoduo.

The Chinese ecommerce company that describes itself as “Costco meets Disney” for its mix of great deals and great fun flew under the radar for two years after its July 2018 IPO. Despite unprecedented revenue growth -- the company did $1.9B in top-line revenue in 2018, its fourth year in operations -- its stock, PDD, climbed slowly to only $33 by the time COVID locked down the US.

Then COVID unleashed the beast. In April, PDD broke $40. In May, it climbed over $60. It closed June at $85. That explosion, of course, caught the attention of the tech Twitterati.

In May, Y Combinator’s Anu Hariharan wrote Pinduoduo and The Rise of Social E-Commerce. In July, Acquired dropped Pinduoduo. In August, Turner Novak went deep in Pinduoduo and Vertically Integrated Social Commerce. Packy even poked fun at all of the attention the company was getting and the US copycats that were sure to follow in a deck (Packy note: I was bored).

As the temperature outside dropped, things cooled off for Pinduoduo in the fall. By late September, PDD fell back down to a more modest $71. The write-ups and podcasts slowed to a trickle. We’d acclimated to the awe. Nothing shocked us anymore, not even a business that doubled revenue to $4.3B in 2019as a five-year-old company.

And then it RIPPED. As growth stocks around the world flew, PDD flew further and faster, rising as high as $212 per share in mid-February, good for a market cap north of $250 billion.

Since then, due to a mix of China fear, the departure of its founder Chairman, and reversion to the mean, PDD has fallen over 50%, back down to where it stands today, a nice, palindromic $96.69 per share for a market cap of $122 billion.

It’s been a bumpy ride. Where’s it all going to shake out?

Would PDD’s $250B fall market cap still stand absent regulatory concerns? Or is PDD still overvalued at $122B? Is it just kind of just like a Groupon for fruit? Groupon grew quickly too... before it fell just as fast.

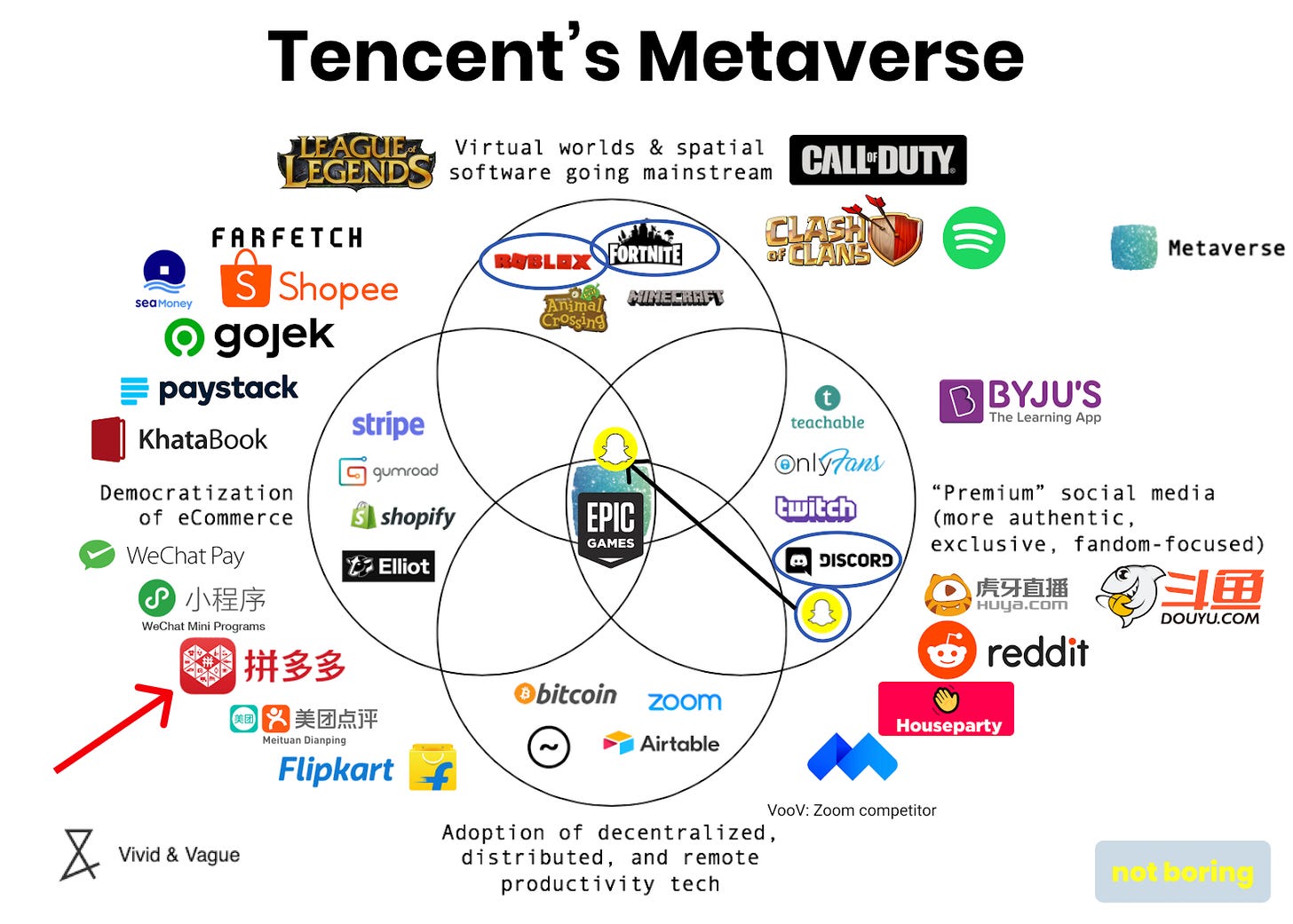

Whether you’re a bull or a bear, Pinduoduo is an absolutely fascinating company that has created, remixed, and popularized key innovations like team buying, “Interactive Ecommerce,” and Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M). Fans argue that PDD brought the shopping mall to customers’ phones for the first time. No one can argue that its ascent from $0 to nearly $10 billion in revenue has been anything short of spectacular. In the bullest of bull cases, it even has a shot at powering commerce in the Metaverse, backed by its largest outside shareholder and Metaverse-kingmaker, Tencent.

But questions remain. Under “new” leadership, will Pinduoduo continue to innovate, or will it slowly blend into the Chinese ecommerce landscape as it steals features from its bigger rivals, and they do the same to it?

Today, we’re going to explore PDD’s last year before debating whether its stock is a buy or sell. (Of course, this is for entertainment purposes only, and is not investment advice!) When we wrote about Agora in April, Lillian took the bear case, and I, as usual, took the bull case. For PDD, the roles are… exactly the same. Lillian’s playing the pragmatic bear, Packy is playing the wide-eyed gweilo optimist. Before we get there, we’ll cover:

A Brief History of Pinduoduo

What Does Pinduoduo Do?

Can PDD’s Model Work in the West?

Recent Developments: Leadership, Grocery, Agriculture, and Payments

The PDD Bull Case -- Packy

The PDD Bear Case -- Lillian

Beyond Pinduoduo

A Brief History of Pinduoduo

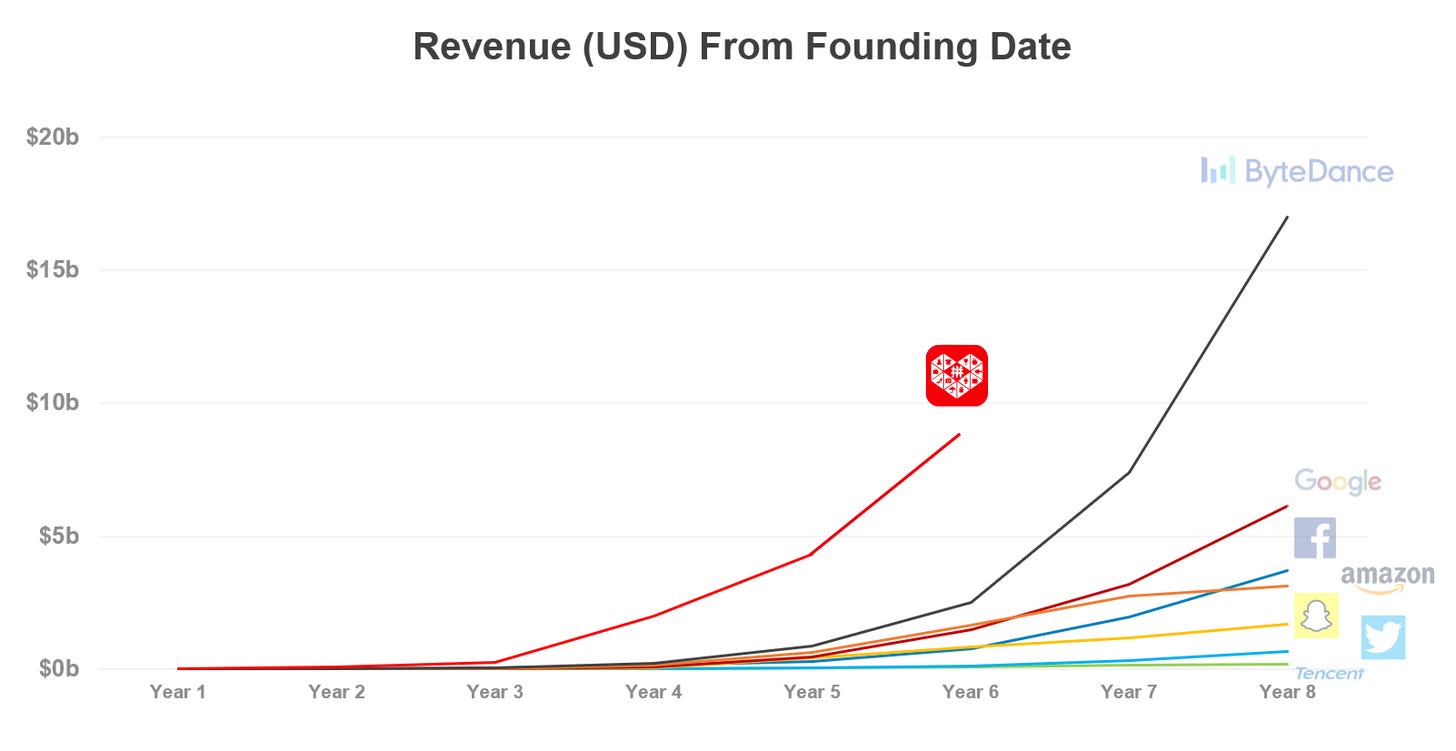

Pinduoduo’s meteoric rise is unprecedented. In just six years, the company, founded by Colin Huang in 2015, reached $9.2B in revenue on the fastest revenue growth trajectory of any company in history. It hit the $100B market cap mark faster than any company in history, too.

That kind of growth attracts attention, and Pinduoduo has been well-covered. If you want to go super deep and get the full backstory, we highly recommend you check them out:

Audio: Business Breakdowns & Acquired & Tech Buzz China

Text: Anu Hariharan & Turner Novak

Deck: Matthew Brennan

For today, we’ll stick to the bits that will be most important for the rest of the piece, including giving the new CEO and Chairman Chen Lei a little more shine. Investors were rightly concerned by Founder, CEO, and Chairman Colin Huang’s departure from his company; they should know that they’re in familiar hands with Lei.

From that perspective, the first thing to know is that both Lei and Huang are geniuses with a long history of studying and working together.

Huang, Pinduoduo’s founder, grew up humbly in Hangzhou, the home of Alibaba. His prodigious math skills took him to the upper-class Hangzhou Foreign Language School at age 12 and to Zhejiang University to study computer science on scholarship in college. The president of the University called Colin personally to persuade him to attend. During college, he interned at Microsoft in both China and the US, and spent time on online forums, where he met NetEase founder William Ding. Ding opened doors for Huang, introducing him to a who’s-who of Chinese tech, including SF Express founder Wang Wei, Tencent founder Pony Ma, and BBK Electronics founder Duan Yongping.

Yongping proved to be an especially important friend and mentor: after Huang graduated from a Masters program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, for example, Yongping convinced him to join Google pre-IPO. That decision made Huang millions. He later backed Huang’s startups and even took him to lunch with Warren Buffett in 2006.

That same year, while at Google in Mountain View, Huang was tasked with launching Google China along with Dr. Kai-Fu Lee and a small team. Part of the job was flying back and forth between China and California to get even minor changes approved by Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and he hated it. In 2007, he quit and began his entrepreneurial journey by launching ouku.com, an online electronics store.

With him at Ouku was an R&D Architecture Engineer named Chen Lei. As impressive as Huang’s math skills were, Lei’s may have been superior. And Lei had the medals to back up his world-class brilliance.

In 1996, the 17-year-old Lei won Gold at the International Olympiad in Informatics in Hungary, and he came back the next year and grabbed a Bronze. He attended Tsinghua University, widely recognized as the best Chinese university, and afterwards obtained a PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, like Huang.

Lei attended Wisconsin a few years before Huang, so the two didn’t meet there, but after stints at Google (like Huang), Yahoo!, and IBM, Lei moved back to China in 2007 to work at Huang’s first startup: ouku.com. The duo has worked together ever since.

In 2011, Lei went to work for Huang’s online gaming company, Xinyoudi Studio, as CTO. Four years later, Huang got the band back together at Pinhaohuo, a DTC fruit company that was the predecessor to Pinduoduo. Lei was a member of the founding team in 2015, and was promoted to CTO in 2016.

Pinhaohuo lasted only a year as a standalone company, but it did two things that would contribute to Pinduoduo’s eventual success: WeChat and Logistics.

WeChat is China’s most popular messaging app. Today, its 1.2 billion users spend more time on WeChat than Americans spend on all social media apps combined. It’s a huge firehose of traffic... that the incumbent Alibaba couldn’t touch. WeChat is owned by Alibaba’s rival, Tencent, and as Turner points out:

Pinduoduo’s primary competitor today, Alibaba, had also banned its sellers from using both WeChat and WeChat Pay. Its biggest incumbent competitor was un-incentivized to react to this newfound distribution channel.

Hamilton Helmer fans will recognize that as one of the 7 Powers: counter-positioning. It worked beautifully. By September 2015, Pinhaohuo was the #1 free app in China, and handled over 100k orders per day, facilitated by its use of WeChat’s WeChat Pay, which made small transactions frictionless and affordable.

The influx of demand for extremely perishable items (fruit) also forced Pinhaohuo to beef up its logistics. According to Turner, a surge in demand for lychees led Pinhaohuo to add 100 new ops employees, open six new warehouses, and reduce turnaround times dramatically. “Within a month, most fruit spent only a few hours in any of PHH’s six fulfillment centers,” Turner wrote. “The time from farm-to-table was often no more than two or three days.”

Pinhaohuo also opened up their logistics beyond early partner SF Express (founded by Huang’s friend and investor, Wang Wei) in order to meet growing demand, and built features that let couriers bid for orders in real-time. They both tapped into China’s robust and affordable local logistics network, and built software to wrangle some of the chaos.

When Huang merged Pinhaohuo with his gaming-commerce company, Pinduoduo, in 2016, the combined company had tens of millions of users, gaming DNA, and the logistics backbone to fulfill all of the demand that might create. Pinduoduo means “Together, More Savings, More Fun;” the name literally described exactly the combination the company was going for.

That combination -- dubbed “social commerce” -- was a revelation that took the market by storm. When Pinduoduo entered the Chinese ecommerce race in earnest in 2016, the market was already full. You had Alibaba in first place with Taobao and Tmall, Tencent-backed JD comfortably in second, and no room for a serious third place contender... until Pinduoduo made room with some good old fashioned low-end disruption.

Pinduoduo realized that there was an enormous swath of customers who were either overserved or completely unserved by China’s existing ecommerce platforms. Specifically, while Taobao and JD served first and second-tier cities, those with populations over 3 million people and the bulk of the country’s GDP, there was no affordable option for people in third-tier cities and below, who made up the vast majority of China’s population.

People in these cities had less money but more time. Many had never shopped online, but they did use WeChat. While price is always a strong attack vector, it was a particularly strong attack vector when trying to reach these previously unserved groups. With more time on their hands than their fellow citizens in cities like Shanghai and Beijing, these buyers were willing to do things like, say, play games and tell their friends to buy with them in exchange for discounts.

Starting at the low-end of the market forced Huang, Lei, and team to completely rethink what a mobile-first ecommerce app should look like and prioritize. The result is Pinduoduo.

What Does Pinduoduo Do?

Simply put, Pinduoduo is a 3rd-party ecommerce mobile platform that sells products ranging from fresh produce to apparel to electronic appliances to household goods, among many other categories. PDD pioneered and popularised the “team purchase” model, through which users can group together with others on PDD’s platform or through popular social networks such as WeChat to complete bulk purchases for low prices.

In 2018, venture capital firm GGV released a video walkthrough of the product that you can watch to get a sense of what the app was like at the time:

Business Model

Team purchase is both a fun, gamified experience for users, and one hell of a customer acquisition hack. Just six years old, PDD surpassed 800 million active buyers in Q1 2021, mostly off the back of users inviting each other into the product.

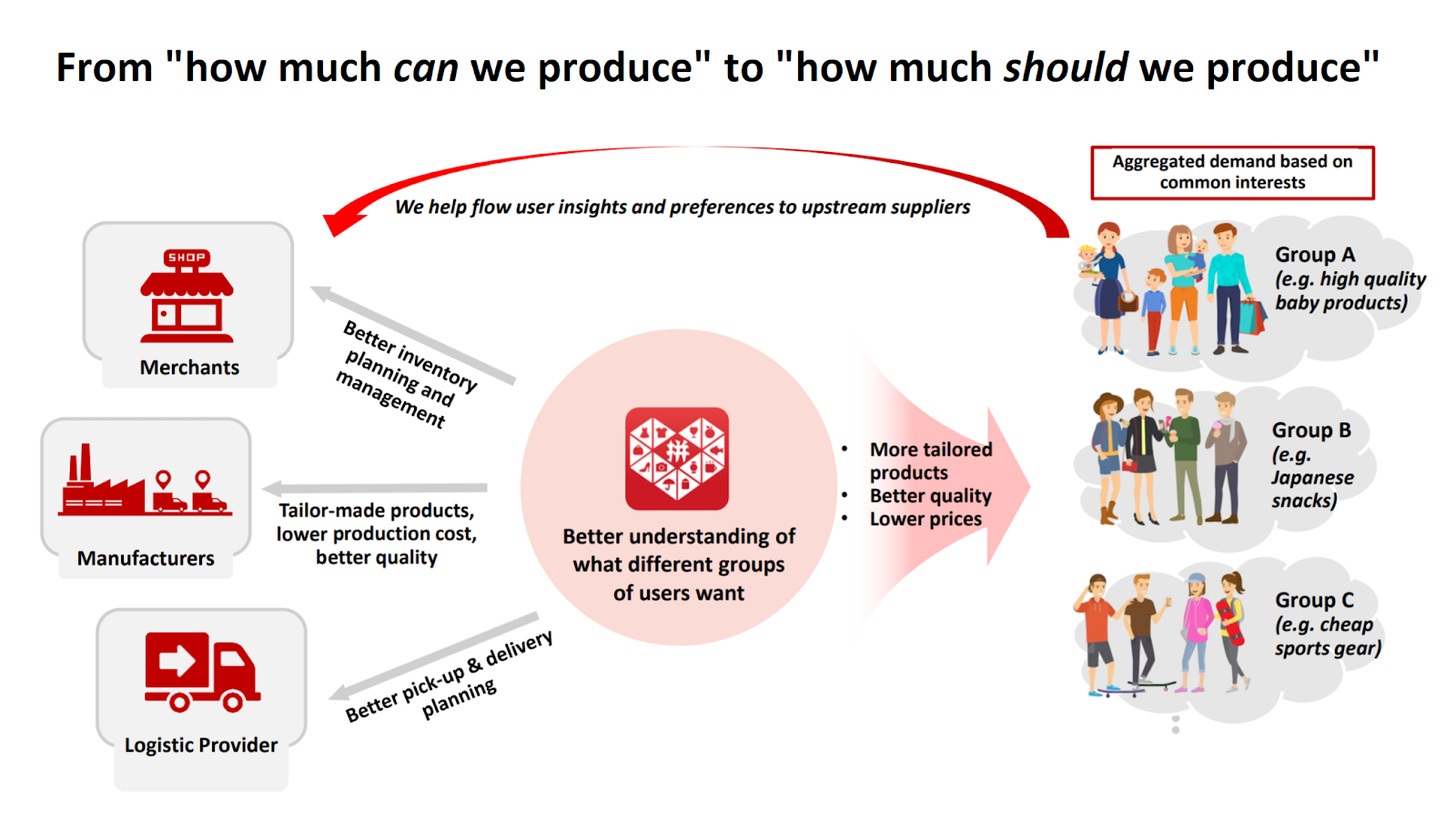

Like a good Aggregator, Pinduoduo used its lively user base to attract 8.6 million merchants as of 2020, on its own terms. PDD leveraged its customers’ combined buying power to pull lower prices and customized products out of a cohort of commoditized suppliers, in a model that is now commonly known as Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M).

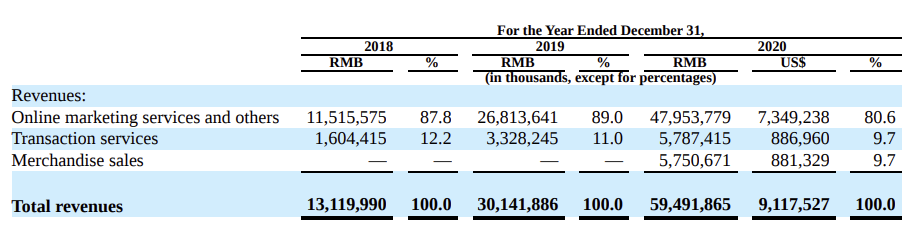

Also like a good Aggregator, PDD makes the majority of its revenue from the supply side.

Similar to Taobao, Pinduoduo monetises predominately through advertising, but it also generates profit through the B2B service marketplace (what they call transaction services) as well as direct sales (here as Merchandise sales).

The fact that 80% of PDD’s revenue comes from advertising says a lot about PDD’s goals: like any advertising-based business, its job is to get people to come to the app and keep engaging, and to sell merchants increasingly creative ways to convert that attention into sales. One key advantage PDD has is that, like TikTok, it’s historically been feed-based instead of search-based. That means that new merchants should have an easier time getting noticed, especially if they buy increasingly integrated ad units.

PDD also offers additional services to merchants (for a fee, of course), including:

B2B service marketplace for merchants: connects merchants with livestreamers, digital store designers, and logistics providers, among other services, for a fee

E-waybill system: a digital platform that automates the shipment labels printing, and tracks and records order fulfilment history and shipment status in real-time for buyers

Duo Duo University: provides training resources and merchant support to help them better engage within the platform

Theoretically, the relationship is a win-win. PDD pushes demand directly to manufacturers, increases their profits by cutting out the middleman, and incentivizes them to spend most of that profit on ads and services with Pinduoduo to keep the magic alive and the profits growing. The ad model also shapes how PDD’s product has evolved.

Product Overview

While Turner’s 2020 article and GGV’s video document Pinduoduo in its heyday of experimentation and counter-positioning relative to Taobao and JD.com, Pinduoduo has since entered middle age. Now, it’s about stability and the core e-commerce engine, and its layout looks more and more like a stereotypical landing page of any e-commerce provider. It is no longer purely low-intent browsing driven; the search bar is loud and clear in the new incarnation.

Have a quick look at the side by side landing pages for PDD, Taobao, and JD.com taken earlier this year. There’s not much difference between the platforms, which is partly PDD changing to become more like its older rivals, but also partly Alibaba and JD.com adapting to what has made PDD successful. One of the starting conditions of Chinese tech has always been that there’s no shame in copying. I guess you either die a toy or grow up to become a utility.

Lillian’s recent PDD landing app walkthrough shows a more gamified, but probably less fun, mature Pinduoduo:

(If you want to see her walkthroughs of the whole app, subscribe to Chinese Characteristics.)

But even as PDD has evolved, its core value proposition has stayed the same. For the user, it delivers three key things:

Cheap products: The products on PDD are cheaper than their equivalent SKU on Taobao. It’s normal to see differences of 10% to 50% in price for the same product on PDD vs competitors’ sites. When 600M people, or 40% of China’s population, survive on $141 per month, and the other 60% all have familial memory of surviving on that amount, it’s no wonder that a majority of the Chinese population’s spending is geared towards cheap and high-value-for-money products. The common brand association people have with PDD is low prices, and in the retail world with a large, price-sensitive population, that is an attractive identity.

Gamified experience: In the Chinese e-commerce space, PDD’s platform generates gamified FOMO like no other. For the user, being able to access lower prices through group buying or coupons adds to the feeling that they are getting a bargain. It also works on the platform and merchant side, as gamified features boost retention, acquisition, monetisation, and user segmentation.

Frictionless delivery: PDD has strict requirements that goods be typically shipped within 48 hours, alongside a seven-day frictionless return period policy for nonperishable products. The frictionless return process is firstly an easy way to convince buyers to try a new purchase - the proposition is that it’s cheap and easy to return, what’s the worst that can happen? It’s also a deliberate feedback loop PDD cultivates to monitor merchant’s quality of goods, and merchants’ search rankings will be influenced by their return rate.

In contrast to JD.com, which is a digital retailer that primarily sells its own inventory, PDD and Alibaba work with a variety of 3rd-party merchants. For merchants, PDD’s key draw has been its lower barrier to entry in the form of lower advertising costs relative to Taobao (a legacy source states that typically only 3 -10% of Taobao stores actually make money) and their more dispersive allocation of traffic.

In the early days, PDD landed producing factories that sold their wares directly at lower costs, as opposed to the middleman retailers that Taobao typically attracts. In convos with a few sellers on PDD, they remarked to Lillian that they switched over from Taobao since advertising costs on that platform has become a need-to-have rather a nice-to-have, which meant that as they were unable to make a profit selling low-cost items.

Can PDD’s Model Work in the West?

Once people understand how PDD works for the first time, the obvious next question is: can someone make it work in the west? And if so, how?

Unsurprisingly, PDD’s success has attracted copycats, both at home and in the west. Some, like stealth Y Combinator grad Supermall seem to be heavily, uhhhh, inspired by Pinduoduo. While the product hasn’t launched, the aesthetic certainly looks familiar.

Supermall isn’t the only one. Two more recent YC grads -- Minimall and Zapt -- explicitly bill themselves as the Pinduoduo for Europe and Brazil, respectively.

Even before Pinduoduo was born, US companies had tried unsuccessfully to make online shopping more social. On Acquired, co-host David Rosenthal said that he looked at a number of companies that tried to leverage Facebook’s social graph to build social commerce experiences when he was a VC at Madrona. He almost invested in one, and was fortunate to miss out, because the company failed when Facebook throttled its ability to use the algorithm.

Many will fail at trying just Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V PDD. The company’s success is dependent on a number of chain-linked factors, both of their own design and as a consequence of the market in which they operate. Acquired highlights four pillars that made Pinduoduo possible:

Distribution. Building on WeChat meant that Pinduoduo customers could frictionlessly share deals with all of their existing contacts in a way that’s not possible in the US.

Cultural Familiarity with Group Buying and Social Commerce. People in the US love to go to the mall together, but thus far, that hasn’t translated online. In China, both offline and online, group buying and negotiation is a more common practice, so forming teams to buy and negotiate on PDD was a familiar behavior.

Logistics Network. Thanks to the existing e-commerce giants and the modular approach they took to distribution, China already had a robust logistics network that Pinduoduo could plug into, including low-cost couriers. If you’ve shipped something via FedEx or UPS recently, you’ll understand that logistics in the US are not cheap enough to make the economics work on such low-price items.

Payments. Most of the items sold on Pinduoduo, particularly in the early days, were super low cost, like fruits worth less than a dollar. In the US, transaction fees and payment delays would make those transactions economically infeasible. In China, however, cheap, fast mobile payments are the norm. It was possible to sell fruits for next to nothing and still eke out a margin for the merchants and PDD.

Frictionless mobile payments played another important role: they made Pinduoduo’s virality possible. Howard Xu, a former-VC-turned-entrepreneur told Packy that in 2017 and 2018, there were 50 PDD copycats in the US, including one founded by a PDD exec, all of which failed for a counterintuitive reason: people in the US don’t often pay on mobile, so mobile checkout conversion rates suck.

In China, nearly all payments are mobile, and mobile checkout has 80-90% conversion. In the US, mobile checkout conversion is (or was then) 20-30%. That’s an obviously huge difference for each individual shopper, but it’s particularly important if your product relies on social sharing. Here’s why:

If only 25% of US shoppers make it through the mobile checkout flow, then, not even taking into account that only some fraction of people who checkout share, there’s only a 6% chance that a second person completes a purchase, only a 2% chance for person three, and a 0% chance that anyone beyond the third person completes a purchase. Payment friction stops US mobile social shopping virality before it starts.

Pinduoduo benefited from market tailwinds and unique… Chinese Characteristics, and took advantage by making smart strategic decisions. In order for a US company to successfully copy PDD, it would need to pull off all of the following: C2M, gaming, targeting third-tier cities, product selection (produce and perishable items), feed over search, team buying, community group buying-like dynamics, advertising, low take rates, and more.

It wouldn’t work, for the same reason that low mobile checkout conversion stops virality: a copycat would need to pull off all the steps, each of which has a sub-100% likelihood of success. Being overly generous and assuming that they’d have a 50% chance of pulling off any given step, just hitting all ten listed above is a 0.1% probability. That’s before taking market factors, or any of the thousands of other little things PDD does into account.

All to say that it’s abundantly unlikely that any western company could successfully copy Pinduoduo straight up. The smart ones, though, are taking bits and pieces and tightly integrating them into their products and business models.

Take Snackpass (full disclosure: Packy is a small investor). As Hariharan wrote:

Snackpass, a food app for college campuses, has built social experiences into their product. Students can send gifts to each other or hatch virtual pets together by ordering food via the app. These interactive experiences encourage increased usage of the company’s product.

That was one of the things that made me want to invest in the company: they took the pieces of Pinduoduo’s model that made sense for their product and customers. College students actually look a lot like Pinduoduo’s customers: low (no) income, social, used to sharing, hyperlocal. Sending gifts, ordering meals together, and even playing games are all-natural extensions.

Or look at Italic. On Invest Like the Best, Italic CEO Jeremy Cai explicitly called out Pinduoduo’s influence on his business:

If we actually look to Asia, this is where a lot of the inspiration for Italic came from… The most notable player here has been Pinduoduo. The exciting thing that they do, obviously, besides the group buying mechanics, which I think is very hard to replicate here, is that they actually source straight from factories. And the difference with Pinduoduo was that they source from basically everyman factories, so you're not really caring about quality, in that case, you're caring about price point.

Smartly, he also highlighted how Italic is different: “Hey, we're going to actually find, not crappy manufacturers, but actually really legit established manufacturers, and actually bring that manufacturer online.”

Italic does C2M, but they modify it to meet what their customers demand. In the end, they deliver a product that, like Pinduoduo, is inspired by Costco, and like Pinduoduo, goes direct from the manufacturer to customer, but unlike Pinduoduo, Italic emphasizes quality over price.

Fevo is a social cart that’s found initial product-market-fit in event ticketing. Fans can buy tickets to sporting events and concerts together, and unlock group rewards like post-game field access or Jumbotron call-outs. Games and concerts are inherently social; Fevo makes it easier to coordinate, rewards buyers, and gives merchants access to lower CACs and better data.

Now, it’s expanding into shopping and travel, letting people ask friends for opinions on clothes or share flight plans before hitting buy. It’s not trying to slash prices, add mini-games, or go C2M. They just want to remove friction and add a social element.

Snackpass, Italic, and Fevo provide a blueprint for western companies: take the features that make sense for your market and model, leave the rest, and add your own flare. That’s what Pinduoduo itself did, approaching the problem fresh from the view afforded by the team’s unique background and experiences.

While others take bits and pieces of what Pinduoduo has done to date, Pinduoduo itself needs to continue to innovate and stay ahead of the curve before obvious competitors like Taobao and JD, and less obvious ones like Kuaishou and Douyin, can recreate some of PDD’s magic. And it needs to do that without its founder.

Recent Developments: CEO Exits, Grocery, Agri, & Beyond

An academic paper on the sustainable development of business platforms framed platform e-commerce lifestage progression into two stages, spread and evolution.

At the spread stage, the role of platform provider focuses on forming “incentive to participants” through “Low price + Social contact” strategy and “Gamification + brand channel” strategy. At the evolution stage, the provider’s role is transformed into manager of products/services quality and revenue structure.

With the utilitarian product layout and other key changes, it seems like Pinduoduo is undergoing the shift from spread to evolution before our eyes.It’s had to grow up fast.

Normally, even the most successful six-year-old companies are still the young guns, catching incumbents by surprise and disrupting them, led by energized CEO/founders who are just starting to hit their stride after spending the first few years in a constant battle just to stay alive, find product-market fit, and then build a replicable machine around their fast-growing baby.

At the same point in Facebook’s life, people were still scratching their heads at Bono’s fund investing in the company at $23 billion, and Zuck still had two years left as a private company CEO. Facebook hadn’t even started its harrowing, company-threatening transition from desktop to mobile.

Six-year-old Pinduoduo, on the other hand, is on pace to do nearly $20 billion in revenue, just surpassed Alibaba for the most active buyers, and is trying to prove that it can move upmarket and expand its offerings in a second act. The company is doing all of this without its founder, Huang, who suddenly left his Chairman seat. He’s already worth $34 billion on paper, and the 37th richest person in the world.

In this new chapter, Pinduoduo is focused on three things:

Continuing to innovate and compete without its founding CEO

Going back to its roots and building the world’s biggest grocer

Moving into payments

Departure of CEO

On March 17th 2021, Colin Huang sent waves through the tech world by announcing his resignation as Chairman of Pinduoduo’s board. The quiet Huang, who wouldn’t even get on a plane to ring the bell at the Nasdaq for PDD’s listing, stepped down first as CEO in 2019 and then left the seat of strategic power in March 2021 to become... a food scientist. Explaining his decision to shareholders, Huang wrote:

When we are young, our teachers always ask us what we aspire to become when we grow up. Like many others, I declared that I wanted to be a scientist. Alas, in the blink of an eye, I am already in my forties. It is probably unlikely for me to become a true scientist. But if I work hard and combine the chemistry that I loved in high school, the computer science that I learnt in university, and the operation experiences I acquired at work, maybe I can still make something meaningful happen.

In his departure shareholder letter, he reflected on the catalyst that made him step down, the first is the impression that scale and efficiency (of which he is famously known for) has reached their limit for PDD. The second is that the great accelerant that is COVID has sped up PDD’s transformation from an asset-light third party model to a more asset-heavy one.

As the core competence of the company shifts towards the heavily operational or the cutting edge, Huang indicated that it is time a new generation of managers need to take up the mantle. The reaction to this has been mixed. Commentators point to this stepping back as one of the latest founders (another was Zhang Yiming of Bytedance) to leave the limelight for fear of Chinese regulators’ increased scrutiny. Others have pointed out that Huang’s mentor Duan Yongping, the low-key founder of OPPO and Vivo smartphone, also retired at age 40 and set up a charitable foundation. The mentor who once took Huang to lunch with Buffet (and thus apparently, introduced him to the idea of float) seems to continue to have an outsized impact on Huang’s life choices.

Structurally, Huang hasn’t been involved in the day-to-day management since last July, when Chen Lei took over as CEO. Colin’s voting shares have been entrusted to the board, and he has pledged not to sell his shares for a further three years. Delegation of power is usually a vote of confidence for the management structure he’s built. It remains to be seen whether this was a bold move that unleashed a new phase of development for Pinduoduo or a quiet changing of the guards.

Lei’s first test? Going back to Pinduoduo’s roots and winning grocery.

Duo Duo Groceries and the World’s Biggest Grocer

In walking around Pinduoduo and Lillian’s shared base of Shanghai these days, one can’t help but notice the half-revolutionary, half-buddhish phrase ‘不忘初心’ blazed across the walls and buildings. The phrase translates roughly to: “Not forgetting your original intent.”

It makes one wonder whether Pinduoduo had been reflecting on that phrase when it embarked on a return to its agricultural roots in 2020, first with Duo Duo Groceries and then with the announcement that it intends to become the world’s biggest grocer.

PDD started in the grocery space initially in 2015 as a fruit seller, and still holds a strong position in agricultural produce to this day. In 2020, PDD sold RMB 270 billion ($42 billion) worth of agriculture-related products, doubling from 2019 and cementing the company’s position as the largest agriculture platform in China. After years of widening their product SKUs, PDD has decided to double down on what made them a breakout success in the first place.

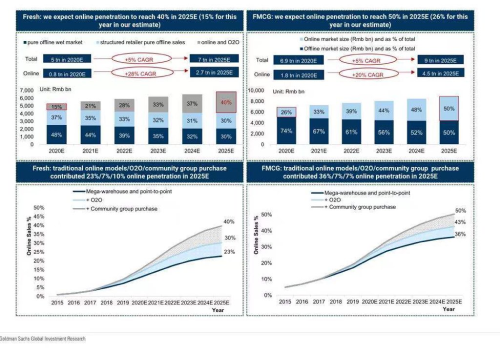

There are good reasons for the move. In 2019, McKinsey estimated that China’s retail grocery market was worth 5.2 trillion RMB ($794B), with only 10% of that currently online. Chinese consumer tech companies love the high frequency purchase pattern of groceries as they are all looking for ways to drive organic traffic to their own apps. A large and fragmented market with limited digital online penetration seems like a great place for PDD to leverage it’s C2M model to drive efficiency throughout the supply chain.

PDD has made its first major move into grocery in the form of Duo Duo Groceries, which piggybacks on the current community group buying trend in China. Community group buying (CGB) has been quite the hot topic in China during the shut-in year that was 2020. It’s a new business model that leverages freelancers (in the form of community leaders) to acquire new customers, aggregate customers’ grocery demands and ensure last-mile delivery to them. This model allows platforms to lower customer acquisition and servicing costs, providing more favourable unit economics for the notoriously low ACV, low margin online grocery category.

Digitalising the grocery buying process through intermediaries is part of PDD’s more extensive and overarching effort to reach more users. As users are more loyal to local group leaders they know than to the platforms, the platforms and PDD in particular try hard to form direct relationships with group leaders, including giving up valuable real estate on their landing apps for the effort. Duo Duo Groceries in the middle of the PDD app and one can’t jump to another screen nowadays without being offered an enticing time-limited discount to buy some eggs or chives.

There’s been a lot of competition in CGB - Meituan, Alibaba, Didi and an armful of startups are duking it out for supremacy. Everyone sees the same potential in groceries as PDD; namely, that it’s one of the last reservoirs of significant consumer demand. PDD might be thinking a couple steps ahead, though, just like it was when it utilised Pinhaohuo for user aggregation. PDD might be using CGB to train consumers to deeply link all things agricultural to its brand, while investing deeply into the supply side of agriculture and then using C2M to connect both parts. PDD’s annual reports reveals the systematic way they are approaching this:

We take a systems-based approach to this and view the entire agricultural value chain in three key parts: upstream production, midstream transportation and downstream consumption. At the upstream, we work with farmers and local partners to reorganize small-scale farms into co-operatives and introduce know-how and technology in sustainable and precision farming to achieve better efficiency and economies of scale. At the midstream, we continue to explore potential collaboration with logistics companies to develop a nationwide logistics network optimized for the delivery of perishable agricultural goods. At the downstream, we help farmers sell directly to our users and provide trainings to farmers on operating online agriculture business. We seek to create long-term structural changes that would improve our users’ experience in buying agricultural products online and contribute to the value creation of the agriculture industry.”

Pinduoduo 2020 Annual report

PDD is going deep into the agricultural production chain and putting down investments along the way. It represents a departure from their usual asset light model, but one that could yield far greater returns given the untapped potential of the market. It’s a promising show of flexibility and willingness to adapt when market conditions demand a new approach.

The company is even willing to lower its dependence on its main channel, WeChat.

Moving into Payments

The story of Chinese tech is often the story of mobile payments as the great enabler. While companies are able to get big quickly by using existing providers like WeChat Pay and AliPay, there are a lot of advantages to owning your rails at a certain scale. To that end, Pinduoduo unveiled Duoduo Pay in December 2020, which has allowed it to tap into the e-commerce infrastructure layer. Its features are still minimal -- bank card linkage, account recharging, and withdrawals -- but it does allow PDD to slowly move away from dependency on WeChat Pay, to whom they paid RMB 516 million ($74.6 million) for payment processing in 2019. It also allows them to close the settlement loop within its own ecosystem.

Not bad for a year’s work, particularly in the midst of revenue-doubling growth and a leadership change.

Now that we’re up to speed with the fast-moving Pinduoduo, it’s time to make the bull and bear cases. As you’ve probably picked up, there are real arguments to be made on both sides. Pinduoduo’s sustained success is far from guaranteed. That doesn’t mean that Packy can’t dream up a wild bull case, though…

The PDD Bull Case -- Packy

There are two ways to make the bull case for PDD: one is to point out that it’s likely undervalued based on today’s numbers thanks to meaningless noise, and the other is to talk about its potential to run more and more through its machine.

PDD Bull Case by the Numbers

Let’s take the first first: PDD is likely undervalued today based on noise.

Pinduoduo’s winter 2020-2021 ascent was part of a broader market rise fueled by low interest rates, free money, and an appetite for growth. No one does growth better than PDD. But it was also driven by an absolutely monster 2020 Q3 in which it grew GMV 73% YoY, Revenue 89% YoY, MAUs 50% YoY, and Spending per Active Buyer by 27%. The perfect storm of eye-popping growth in a market that was hungry for it had investors ravenous, and they doubled PDD’s market cap to over $267 billion by February. Then the wheels started falling off, for China tech in general, and its highest flyer, PDD.

There are real fears around China tech: the ever-present questions about accounting reliability have been joined by fear over the CCP’s newly aggressive stance around regulations and enforcement meant to curb the power of big tech:

Alibaba’s Jack Ma disappeared

The Ant IPO was pulled

Regulators ordered ridesharing giant Didi to take down its app just days after a US IPO

Recently, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) issued a rule that any Chinese company with more than 1 million users must undergo a security review before going public abroad in a thinly-veiled bid to keep Chinese companies from listing in the US.

Lillian wrote an excellent piece on the subject, Let the Bullets Fly for a While. All told, the CAC and CCP’s growing involvement in the tech sector has had a chilling effect on foreign demand for Chinese stocks. It also means that investors willing to take the risk can get Pinduoduo at a Pinduoduo-like low price (assuming the CAC or CCP broadly don’t pull out any nuclear options).

Since last July, PDD is up a measly 23% despite putting up mouthwatering numbers over the same period. For the full year 2020, it did $9.2 billion in revenue, up 112% YoY. From Q1 2020 (which, to be fair, was hit by COVID) to Q1 2021, the last reported quarter, it grew revenue 239% to $3.4 billion for the quarter. It’s growing revenue faster than any company in history, pacing ahead of ByteDance, which in addition to only dealing with digital products, is able to generate revenue worldwide. PDD, as of now, operates only in China.

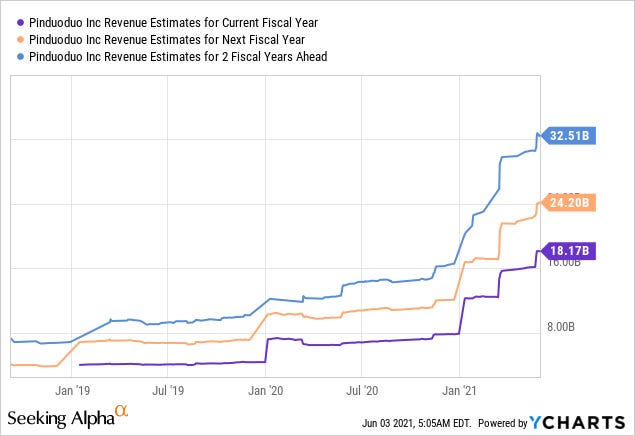

One reason the stock may be lagging is that analysts are dramatically undershooting sales growth, estimating 33-34% growth for the next couple of years when sales have grown at a 112% 5-year CAGR. It’s hard to wrap your mind around growth that consistently high.

Of course growth will come back down to earth eventually, and PDD will mathematically run out of new customers in China in a few years even at 10% growth. But even assuming that slower revenue growth, today’s price represents a Forward P/S of around 6.7x, which is higher than comps like BABA (3.6x) and AMZN (3.7x) but PDD is growing nearly 4x as fast as either of them and improving profitability by the quarter as it scales.

Bears would point out that PDD is still unprofitable, even at this massive scale. That’s true, but because of its model -- it collects cash from buyers upfront before paying out merchants -- it generates a ton of cash. PDD generated $3.8B in Free Cash Flow (FCF) in 2020, and is expected to generate $5.2 billion in 2021, up 37% YoY.

Importantly, PDD is now the biggest ecommerce platform by number of active buyers. In its Q1 2021 earnings announcement, it reported that it had 824 million active buyers over the last twelve months (LTM), surpassing even the giant Alibaba.

In March, PDD reported that each of those buyers is spending more; annual spending per active buyer increased 23% from 2019 to 2020, to $342.

That’s the real bull case: PDD has a huge number of active customers, spending more money year over year, and a machine through which it can sell them evermore products.

PDD’s Interactive Commerce and C2M Machine

The second prong of the bull case is this: it has built a machine, and it can run a lot more through it.

Pinduoduo isn’t just a fruit-seller or a low-end goods marketplace. It’s built an engine into which it should be able to plug any product, from fruit to fashion, physical to digital.

The engine has two interconnected parts: Interactive Ecommerce on the demand side and Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M) on the supply side.

Interactive Ecommerce is a term Matthew Brennan coined for “combining community, entertainment, and recommendation to provide more value for money to the end user.”

Brennan painted a clear distinction between social commerce and interactive ecommerce: it’s not as easy as a social network saying, “Your friend bought this!” Interactive ecommerce companies create an experience that combines community (social) with entertainment and recommendations, all with the principle of value at the core, to create a digital analog to the best parts of real-world shopping. The company he uses as a case study, of course, is Pinduoduo.

PDD does a number of things to create the interactive ecommerce experience:

Entertainment: Mini-games scattered throughout the app; rewards for check-ins to encourage daily engagement; constant streams of new deals and games; they even have non-shopping entertainment like short-form videos, and opportunities to buy tickets to real-world movies with friends at a discount.

Community: Team buying; pop-ups letting you know when others have bought; seamless experience across WeChat and Pinduoduo app; livestreams.

Recommendation: CEO Lei is a trained data scientist and has built up a team of over 100 engineers (as of 2018) focused on PDD’s recommendation algorithm; the feed-based display means more opportunities for random purchases like you might make at the mall.

At the core of all of it is value. Team buying lowers prices. Playing games earns coupons. The recommendations algorithm serves up deals that you need to buy right now.

Those are deals. The value comes from combining the Interactive Ecommerce front-end with the C2M back-end. In order to serve customers at the low-end of the market, Pinduoduo had to cut costs in any way it could. The biggest way it accomplished that was by cutting out as many middlemen as possible. The result is the C2M model and dramatically lower prices.

We’ve discussed the importance of C2M above, but for our purposes in the bull case, what’s key is that interactive ecommerce and C2M form one cohesive but modular machine into which they can feed new products and experiences.

Pinduoduo isn’t just a fruit company. It’s not necessarily even just a “cheap product” company. It’s a company whose business model is set up to deliver a fun experience and value for whatever it sells. It can do that in a lot of ways.

One obvious move is to go upmarket and sell higher-end versions of the same types of products to its customers. As the lower-tier cities Pinduoduo has always served upgrade their retail, Pinduoduo has the opportunity to move upmarket with them. Just as Alibaba’s Tmall serves a more brand-conscious customer, might PDD release a separate higher-end platform, backed by the same engine? Might they just put it right in the app and rely on the algorithm to serve the right products to the right people at the right time? It feels like a natural extension.

Currently, its focus is on bringing interactive ecommerce and C2M to grocery. Duo Duo Grocery isn’t team buying (the company would say that it’s not community group buying, either), but it is interactive ecommerce. It shows you who else in your neighborhood is buying which products and even gets you all to show up at the same place at the same time to pick up your haul. It’s using online mechanisms to get people together offline. And it does use the C2M model, aggregating demand and letting farmers deliver a bulk order to one location instead of worrying about sending a box of cherries or some lettuce to each individual buyers’ front door.

Pinduoduo is returning to its agricultural roots, which sound unsexy. It’s easy to miss the importance (Packy did, until Lillian showed him the light). But it’s key. Here’s the case.

The market in China for agricultural products is enormous -- roughly $1.2T annually by 2025 as estimated by Goldman Sachs GIR-- and online penetration is low.

The market exhibits a key characteristic PDD looks for: high purchase frequency, which builds a habit and keeps people coming back. And unlike the rest of Chinese manufacturing, which is super advanced relative to the rest of the world, its agriculture severely lags the US for a variety of reasons, including bad soil, lack of access to genetically modified seeds, and small landholdings that are a vestige of Communist land distribution. This is an area where Pinduoduo can make a huge impact, and build an enormous business.

The opportunity is so big that Huang left the company in part to focus on moonshot projects in food science. Bezos and Musk have space, Huang has genetically modified fruit that delivers superior nutrition and man-made proteins. Getting agriculture right is particularly important for a country with 4x the population of the US in the same area of land.

PDD has the opportunity to educate farmers and reorganize how agriculture works. It’s training farmers through Duo Duo University -- in 2019, it trained 500,000 farmers -- and hosting AgriTech competitions to encourage innovation in the space.

Pinduoduo can play a pivotal role in reorganizing how food gets made in China by leaning even more heavily on its C2M skills, help farmers predict demand by aggregating it upfront, and can ensure that there’s a market for whatever they make by selling the products through its interactive ecommerce model. The prize if it succeeds is enormous financially, and just as big politically. The government has been focused on improving food growing in China, particularly as bad weather has driven up prices, and if PDD helps them pull it off, that may give them some much-needed leeway with regulators.

This area is more fascinating than I thought, and if you want to go deeper on what PDD is doing in agriculture, give this podcast a listen (or follow along on the company’s surprisingly good blog):

Beyond the immediate stated opportunities, the company has also sent test balloons into real estate and travel, neither of which have made much noise yet. They don’t seem like natural extensions, but dig a little deeper. Could they run both through the interactive ecommerce + C2M machine?

Travel. At some point in your life, you’ve probably been hit up by that friend who organizes the trip to Cancun and gets a free trip if they convince 30 friends to come. The way that works today is that an intermediary strikes deals with resorts and airlines, and then finds campus reps to sell the deal to their friends. Pinduoduo could bring a similar experience online and cut out the middleman, facilitating group travel directly between hotels and groups of people. That looks a lot like interactive ecommerce and C2M (or C-to-Hotel, as it were).

Real Estate. This one is a little harder to envision, but one of the riskiest things for a developer is figuring out where to purchase land, and what type of units to build on top of the land. What if Pinduoduo could derisk the process by getting people to pre-commit to renting certain apartments and revealing their living preferences before a single shovel goes into the ground. The app already knows where people live, how old they are, and how expensive their tastes are. It can probably make pretty good guesses as to which people would like living near which others. That’s interactive ecommerce on a more permanent basis. The Consumer-to-Developer model would remove risk, cut out brokers, and facilitate communal living experiences… and, by the way, make it easier to fulfill deliveries when groups of hundreds of loyal customers live in one building.

While travel and real estate may be years away for PDD, they highlight just how many categories can run through the interactive commerce + C2M machine.

The machine isn’t necessarily limited by borders, either. Pinduoduo might expand beyond China altogether. At its current growth rates, PDD is going to run out of Chinese customers soon, and relying solely on expanding wallet share feels like the beginning of a slow death. It needs to look outside China’s borders.

While it’s highly unlikely that we’ll see PDD in the US or even Europe, many developing countries in Southeast Asia and Africa have similar market characteristics to China -- high mobile penetration, price-sensitive customers, quirky local delivery infrastructure, local manufacturing, and more -- that would make them attractive targets.

But why limit our imagination to physical boundaries? I’m going to get a little crazy here for a second, but the combination of interactive ecommerce and C2M also lends itself to the digital world, and particularly web3. Groups of people interacting with each other and playing games in order to earn small amounts of money by transacting directly with each other sounds a lot like Axie Infinity.

Axie breeders sell newly-minted Axies directly to new players; Pinduoduo manufacturers sell their products directly to customers.

Axie players play games to earn SLP tokens that they can exchange for fiat; PDD customers play games to earn discounts on products.

Ultimately, both Sky Mavis (the developer behind Axie) and Pinduoduo understand the same thing, which Sky Mavis co-founder Jeff “Jiho” Zirlin explained like this:

The first principle is: in an attention economy, users who give us their attention should be rewarded.

As evidenced by the company’s revenue split, Pinduoduo is an advertising business. It needs attention, and it’s willing to give discounts and subsidies to get it. As long as they continue to earn attention through interactive ecommerce, and channel it through C2M transactions, it has endless ways to monetize.

Ultimately, the bull case for Pinduoduo is this: PDD is too cheap relative to its growth already, and that’s before accounting for all of the products, digital and physical, low-end and high-end, that it’s going to be able to run through the machine it’s spent the last six years building.

The question is: can it continue to innovate, in the face of competition, without its founder?

The PDD Bear Case -- Lillian

Pinduoduo’s concern is the concern all of us face as we move into middle age: we’re no longer buoyed by the optimism of youth, but we’re laden with our prior misdeeds. Much has been accomplished but the tasks at hand are harder. There’s more competition as others learn the tricks that have made us successful, just as we come to face our own limitations. Friends who were with us in the beginning have parted ways to find their own bliss. (Packy and probably everyone else: Lillian, you ok? Lillian: We’re talking about e-commerce right?) And as always in China tech, things are changing fast and we have to ask: can PDD adapt and thrive?

Yes, we’re talking about the Chinese ecommerce market and Pinduoduo. The bear case consists of seven parts. We’ll take each in turn.

Increased e-commerce and fun competition from the existing players and new upcomers.

One of the many surprising things about anti-monopoly regulation could be that PDD has to face its most formidable competitor on what was once its home turf, protected by counter-positioning. To avoid anti-monopoly allegations, Alibaba and Tencent have both pledged to open up their platforms to each other in a reversal of their previous closed garden approach. Users will finally be able to access Taobao links in their WeChat programs, which may present more competition to PDD. At the same time, Taobao is blatantly cloning PDD with their Taobao Special Offer Edition product, their take on C2M.

That’s not to mention the new kids on the e-commerce block, such as Douyin, Kuaishou, and Bilibili. These entertainment apps have all started building out their own e-commerce fulfillment as we speak. While PDD might have started with the “entertainment + shopping” concept, the new kids are really perfecting it. They also have the added benefits of creators with whom shoppers can form parasocial relationships and from whom they want to buy. If nothing else, by winning the entertainment corner of ecommerce, these newcomers will push PDD towards the more utility aspects of the e-commerce spectrum as they take up valuable in-between hours from people’s attention spans. Kuaishou’s average time per DAU is 99 minutes in Q1 2021. Since Pinduoduo thrives on engagement, anything that competes for its users’ time is a real threat.

Unproven ability to transform into an asset-heavy grocery player.

PDD was able to grow at breakneck speed, because it leveraged Taobao’s starting playbook of becoming the abstract ordering layer. But now, as Chinese internet gets more asset-heavy and moves closer to the technology frontier where deep tech expertise is needed to succeed in logistics and food science, new questions arise. Is it within PDD’s management and operational DNA to adapt to this new reality?

Agricultural produce is really hard. There’s a reason why it’s been a focus area for China for decades, and yet Chinese agricultural yields still lag behind the US. PDD has been a great e-commerce asset light platform; now, it wants to go and solve one of the hardest problems that China faces. That’s very commendable, but we must also appreciate how daunting the the task is.

Paradox of cheap customer acquisition with high sales and marketing costs.

Here’s a mystery: given all of the PDD’s talk about social e-commerce and viral customer acquisition, why does the company spend so much money on sales and marketing? Last year, PDD spent $6.5bn on sales and marketing in a mix of brand building and subsidies for users, a ~60% increase over 2019. Will there be a time when PDD can safely taper off S&M, or is it kind of like enterprise sales, a sort of COGS that’s hidden below the line? The bear case here is that PDD can never turn off the fuse and reach profitability at scale.

Leadership uncertainty.

What is PDD after Colin Huang? That is the question that solicits endless anxiety among the investor crowd. Typically, the departure of a founder will see the company be passed on to professional operators who are steady and will keep the ship sailing. However, when that happens, it’s universally acknowledged that companies will tend to take less risk and pursue fewer moonshots. What PDD will be after Colin’s departure is uncertain, though it’s hard to say that means PDD might be a ‘bad’ company, there is a bigger chance that it will be less of a great company.

The boundaries of Chinese market means constrained growth.

As Packy has observed above, at its rate of growth, PDD is going to hit the Chinese population ceiling almost any day now. They see what every other Chinese consumer tech player also sees: a pie with a predefined size. And they’re not the only ones eating the pie. As discussed, everyone is gearing up to compete in everyone else’s territory. So what about other markets? Internationalisation is hard to do; success abroad is uncertain.

Instead, PDD is betting the house on groceries as one of the last undigitalised markets that they can capture, which will take time to yield (no pun intended) even if they get it right.

With competition from Meituan, Alibaba, Douyin and Kuaishou, growth will be taking a hit whichever way you look at it going forward… unless PDD expands their definition of the world to include the Metaverse, and I wouldn’t hold my breath here. (Packy note: I’m holding my breath.)

Long term brand positioning and defensibility.

I get why PDD wants to move deeper into groceries; it’s a way to build a tangible moat that it has not been able to do so thus far. PDD’s success has been about standing on the shoulders of giants: partly Tencent via WeChat, and partly Alibaba, which educated users and logistics providers on how e-commerce should work. Its trajectory has been fast because it’s easy to be a fast-follower, but that’s a less defensible position. Others can use a similar playbook.

If your brand is about being cheap and fun, there are ways to unbundle that. Other platforms can offer cheaper goods or more entertainment. Being focused on cheap goods means that often you’re attracting mercenary users at the expense of the merchants who have to offer cheaper goods and subsidies. In the long term, there might be a departure of both if another platform offers lower prices or better margins. Currently, PDD is in the midst of a large platform struggle to have a concrete moat, while it is trying many things, there’s no strong evidence yet that they’ll succeed.

Spectre of regulation.

As we’ve mentioned in the Bull case (or if you’ve been reading the news), consumer tech has not been in favour with Chinese regulators recently. PDD already got reprimanded for price dumping with Duo Duo Groceries once, and it could always happen again.

I take a relatively nuanced view of Chinese regulation. I think that there are many factors, including political will and societal benefits, driving regulatory action. Most of the tech regulations thus far in China’s short history have been on the side of consumer and societal welfare. (Of course, that term is a difficult and subjective term to define).

There is a future for Pinduoduo in which they are successful at doing what they plan to do -- digitising the agricultural supply in China -- but the government may decide that it’s not in society’s best interest. Agriculture employs up to 25% of China’s workforce, and employment is a core objective for the government. Will higher efficiency in agriculture mean leaving behind workers who have few transferable skills? The fruit and street peddlers can’t just become data scientists overnight, as their backup option. PDD has to navigate a very fine line here and, unlike Didi, work hand-in-hand with the regulators to avoid negative consequences, both for the business and society at-large.

Beyond Pinduoduo, More Metaverse, More Fun

Pinduoduo created a revolutionary new shopping model that took advantage of all the tools at its disposal at the time: mobile, WeChat, algorithmic feeds, mature logistics networks, and a commerce landscape that had been fully single-player. But while the company gets a lot of credit for creating the social commerce category, and introducing fun into the commerce equation… it doesn’t actually seem like it’s that much fun?

There, we said it. Gaming has given way to gamification. The joy of a novel way to save has turned into a chore. Lillian called it a form of price discrimination -- only the people who have a lot of time and really need the discounts would be willing to take the time to understand the complex game dynamics woven throughout ght app.

For over five years, Pinduoduo has been the most entertaining commerce app. Now apps that are entertainment-first, like Kauishou and Douyin, are getting into commerce. Can they get logistics before Pinduoduo can get fun?

Whether it’s Pinduoduo, Kauishou, Douyin, Taobao, JD, or a completely new entrant, we believe that PDD is a glimpse into the future, one in which gaming and commerce, online and offline, are seamlessly woven together. Shopping in the Metaverse will feel more like a game than shopping on Amazon, or even Pinduoduo, does today. And playing games will have more real-world consequences than they do today in games like Fortnite or World of Warcraft. We’ve seen the very beginning of this shift with Pinduoduo and Axie Infinity, and we would be willing to stake all of our Pinduoduo coupons on a future in which everything becomes more blended, not less.

Pinduoduo actually has a lot of the DNA in place to lead ecommerce into the Metaverse. It’s architected for browsing serendipitously, like you would in a virtual mall, instead of searching, and for going on shopping quests in groups as opposed to alone. It has data on who buys what when, where, and for what price. It’s built for the kind of world envisioned by proponents of an open Metaverse in which consumers shop directly from manufacturers without the need for layers of middlemen. It has the logistics network in place to deliver food and physical items to people for as long as people need food and physical items (read: a long time). It’s even half-gaming company by birth.

For now, Pinduoduo seems to be setting its sights on revolutionizing China’s agricultural supply chain. That’s a move back to its roots instead of a leap into the future. But while Pinduoduo’s current leadership is focused on that, it’s largest outside shareholder, Tencent, is loosely pulling together the Metaverse.

As Packy wrote last summer, “Pinduoduo’s C2M and social commerce models are reshaping ecommerce in ways that may work even better in the Metaverse than they do on mobile.”

This seems a little out there, but bear with us. Jeff Bezos, who knows a thing or two about ecommerce and futuristic stuff, said that the more important questions is not “What will change in the next 10 years?” but “What will not change in the next 10 years?”

In China or abroad, in meatspace or the Metaverse, people will always want to have interactive group experiences with their friends, they’ll always want to cut out the middleman when possible, and they’ll always want good value for their money.

If Pinduoduo can deliver those three things, whether on the farm or in the Metaverse, they’re gonna make it.

Thanks to Dan for editing and to Lillian for teaming up!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Monday!

Packy

Hahaha, I can't believe you used the word "gweilo"; so good. Albeit that's mostly used in Cantonese, for the Mandarin equivalent, you can use "Laowai"

Thanks to you both, really liked the bull-bear format.

One note: the FCF mentioned in the bullcase is much, much too high (many articles and investors seem to get this wrong). This is because, much of the payments and deposits of merchants are restricted cash. This is held in excrow accounts and can neither be used for daily operations nor be paid out to investors and is therefore not part of FCF.

Operating cashflow in FY20 was 28bn RMB and capex was negligable. But between FY19 and FY20 restricted cash increased by 25bn RMB (52bn - 27bn). So FCF was more like 3bn RMB (460mn USD).