Welcome to the xxx newly Not Boring people who have joined us since the last email! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, join 20,xxx smart, curious folks by subscribing here!

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday!

There are over 20,000 of us here now — thank you for making that happen 🙌

If you’ve been here for a while, you know that Slack is my favorite investment. The market, thus far, has not agreed with me.

You didn’t think I was going to go down without making my 6,900 word case, did you?

But first, a word from our sponsor.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Barrel

Barrel is a creative and digital marketing agency run by my friend Peter Kang. The Barrel team has worked with clients like Barry’s, Dr.Jart+, Bare Snacks, ScottsMiracle-Gro, Rowing Blazers, Hu, and many more to build their Shopify Plus sites and marketing strategies across email, paid, and SEO.

Please don’t waste your marketing dollars on poorly done ecommerce websites and paid social campaigns. Work with Peter and the Barrel team to create experiences that deepen your relationship with your customers.

Now let’s get to it.

Slack: The Bulls are typing…

Imagine you haven’t read the title of this post and I told you about an unnamed public SaaS company that:

Builds an essential WFH software product,

Has the second highest gross margins of any of the 54 companies tracked in the BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index,

Is the eighth fastest-growing company in the index, which has outperformed the Nasdaq by nearly 3x YTD.

Bet you’d say, “Sounds like an awesome company. I’d love to buy it, but it must be so expensive at this point. Damn, bummed I missed it.”

And then I’d say, “Nope! You didn’t miss it. It’s actually deeply underperforming the Nasdaq this year.”

“Ahh,” you’d reply, “Underperforming. Now I know what company you’re talking about. Slack!”

From Day 1, I’ve known Slack was a long-term play. It acquires customers slowly, but is incredibly good at retaining and growing with them once they’re hooked. That takes time to pay off. I’ve owned shares in Slack since the day it IPO’d direct listed on June 20, 2019 at $38.50 based on that thesis.

As it tanked, I bought more. It kept dropping, I kept buying. Over time, Slack became my biggest position (full disclosure etc...), all based on the thesis that it would just keep compounding and compounding until one day, everyone woke up to the fact that it was a juggernaut.

When it became clear that we would all be working from home for a long time, I thought I was a genius. I was picturing early retirement and yachts and islands (or at least a trip to an island and a boat cruise). But then, as I wrote about in May, Zoom Zoomed, and Slack slacked.

It was only a matter of time. Slack just had to pick up, right? Wrong. Other than one brief, glorious run leading up to Q1 earnings on June 3rd, it kept sinking. And I kept buying. Any time the market tanked, and I had my pick of “discounted” stocks, I chose Slack. It got so bad that my friend texted me this last week when I took advantage of the Vaccine-Induced Tech Selloff to, you guessed it, buy more Slack:

The Not Boring Portfolio -- the fake portfolio I made to track the companies I write that I’m bullish on -- has done incredibly well, outperforming the S&P 500 by 2.6x and the NASDAQ by 1.8x, except for Slack.

Like Carrie Mathison in Homeland, “I have never been so sure, and so. wrong.”

But I’m not quitting on Slack. Partially because it’s underperformed SaaS so badly during COVID, I think it’s one of the best opportunities in tech. Wall Street hates it because of the threat from Microsoft Teams, but that’s our opportunity. Slack is the rare chance to be contrarian and right by betting on a fast-growing public SaaS company with extremely high gross margins.

I’m openly and unabashedly bullish on Slack. But to keep myself honest, I’m going to lay out my bull case for Slack and would love to hear your counterarguments in the comments or over on Public.

The Slack Thesis

I’ve written about Slack twice before:

Slack co-starred in both essays, but I’ve never given it the solo performance it deserves. I’ve never laid out my bull thesis in toto. So here it is:

Slack is already a top quartile SaaS company trading like a bottom quartile SaaS company because of that age-old worry that “Microsoft will just crush it.”

It’s one of the fastest-growing public SaaS companies in the world with eye-popping gross margins. Slack is world-class at acquiring, retaining, and growing with the fastest-growing companies in the world. As they grow, Slack grows, and revenue compounds while costs stay relatively flat. Slack Connect will turbocharge that compounding by allowing non-Slack companies to try Slack in a lightweight way, and more seamless integrations weave Slack more deeply into the fabric of work.

The narrative about Slack doesn’t even match today’s numbers, let alone its clear compounding potential. A misplaced narrative is my favorite kind of investment.

Slack is hated, and one paragraph plus a question isn’t going to change that. So we’ll need to lay out the case in some more detail. Luckily, writing thousands of words about tech companies is what I do best, and I’m fired up about this one. So let’s go bear hunting:

What is Slack? Most of us probably use Slack, but we’ll try to put it into words. That’s surprisingly hard, even for Slack itself.

Connecting Slack’s Strategy. Slack Connect is crucial to Slack’s strategy.

# by the #s. Slack’s numbers are among the most impressive of any cloud-based SaaS company, and they keep getting better.

The Bear Case: Teams, Mostly. The market thinks Team is an existential threat to Slack. That narrative is wrong, and there’s no better opportunity than an incorrect narrative.

ARK Invest and The Power of Compounding. ARK Invest is long Slack because it understands the impact of compounding over time.

Stickiness, Net Dollar Retention, and Free Cash Flow. Slack’s customers stay Slack customers, and grow with Slack at an industry-leading rate. That’s starting to produce positive Free Cash Flow, and it’s all upside from here.

The Real Threat. Since Slack’s upside is predicated on its ability to acquire and retain young, fast-growing companies, the real bear case is that startups skip the channel-based communication for tools that allow them to collaborate in-app.

Picking Up the Slack. When will Slack stock stop slacking?

A bet on Slack is a bet that technology companies are going to grow, that a platform will beat the inferior monolithic solution, and that communication is at the heart of productive collaboration. Ultimately, it’s a bet that the market is telling itself the wrong story. When the narrative changes, so will Slack’s trajectory.

What is Slack?

“Six and a half years and it’s still kind of hard to explain,” Slack’s CEO Stewart Butterfield told Jim Cramer on Mad Money in early October.

That challenge is reflected in the ever-evolving way Slack describes itself. In March, right before most US companies decided to work from home, Slack defined itself by what it replaces:

In August, Slack defined itself as “where work happens.”

By October, Slack landed on the framing that it’s going with now: Slack is your new HQ.

Stewart explained it to Cramer on Mad Money:

I think maybe the pandemic times make it a little bit easier because we can say Slack is your office when you don’t have a physical office anymore. It’s where work happens. But I don’t know how helpful that ultimately is. It’s always been the kind of thing that people don’t know they want, but once they have it, they can’t live without it.

The difficulty describing itself is core to Slack’s challenges to date, and the idea that once companies start using Slack, they can’t live without it is core to its promise.

At the most basic level, Slack offers channel-based workplace communications software. The company believes that as companies grow, most of the work they do becomes communicating with each other. Its software allows companies to set up channels for each of the teams, projects, and workflows that comprise their business, and to integrate external software to smooth those workflows. It’s maniacally focused on making communication more effective.

It does that by working on the little things that make the overall experience of using Slack delightful. For example, it was the first workplace chat tool to sync your place in a channel across devices, meaning that the conversation on the desktop app would pick up where you left off on mobile. It puts an enormous amount of thought into something as simple as when to send which notifications, as exemplified in this now-famous notification decision tree:

I could keep going and compare Slack and Teams feature for feature, but no one disagrees that Slack is a better product (unless your company does everything in Office, in which case Teams’ tighter integration with its own products is an advantage).

One caveat, lest I come off as too much of a fanboy: Slack can be incredibly distracting and make it seem as if “work,” or something that feels like work because it’s in Slack, follows you everywhere. If you don’t manage your notifications properly (I turn mine off except for @ mentions), you can get sucked into an endless hole of HAPPY BIRTHDAY!!!s, @channels, and cat gifs. Plenty of Slack users hate Slack.

Done right, though it can greatly enhance a company’s productivity by organizing conversations, making anyone reachable at the tap of a keyboard, enabling easy document sharing, and automating workflows via integrations. It can be a company’s OS.

To be the OS, it needs partners. Slack realizes that it can’t build the best of everything. It doesn’t even use its own video product internally; it uses Zoom. Instead, it wants customers to choose the software that works best for them for each thing that they do, and then make that software work better by integrating it into the company’s workflows and communications.

As Butterfield puts it:

For whatever software our customers already use, or whichever software they use in the future, we’d like to make their experience of those tools better because they use Slack… Slack with Slack Branded Feature X is probably less valuable than Slack with Competitive Branded Feature X in the same slot, because now you’re using Slack and you have an integration set up.

And then there’s Microsoft, whose bet is that you’re willing to take a bunch of pretty good software as long as it comes with Excel and Outlook.

Three points illustrate Slack’s commitment to the open platform approach:

Integrations. On page 5 of its most recent earnings presentation, Slack highlighted that there are 2,300 apps in its directory, 700k custom apps and integrations used weekly, and 820k developers actively building for Slack. It’s running Microsoft’s old Office playbook.

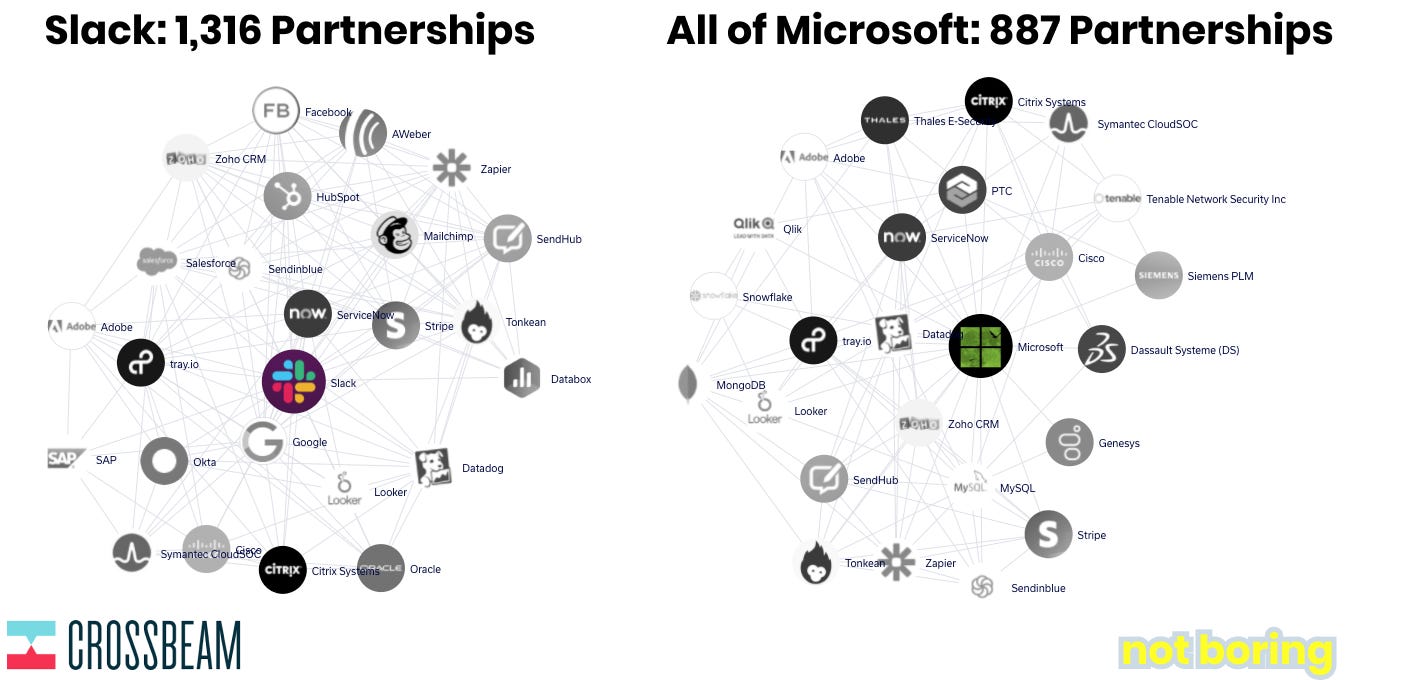

Partnerships. According to Crossbeam, Slack has 1,316 publicly announced technology and channel partnerships, almost 50% more than the 887 Microsoft has across the whole company.

Slack Fund. Slack not only partners and integrates with companies, it invests in them. Slack launched the fund at the end of 2015 in partnership with leading VCs like Accel and a16z to encourage developers to build apps on top of Slack. Today, the fund invests in some leading companies in the productivity and collaboration space. Most notably, Slack invested in:

Asynchronous video company Loom’s Seed through its $30 million Series B,

Buzzy collaborative presentation software Pitch’s Seed and $19 million Series A,

Leading password manager 1Password’s $200 million Series A

Virtual events company Hopin’s Seed, Series A, and Series B

Partnership management company Crossbeam’s (remember them from the last bullet?) Series A and Series B.

All of Slack’s investments have or will have Slack integrations, and it’s not hard to squint and see a loose association of products that, collectively, can take on Microsoft.

While Slack’s product and partner ecosystem can be hard to explain, its business model is straightforward: it is a software-as-a-service (SaaS) business that charges companies a monthly rate for every employee that uses it.

The name of the game for Slack is to acquire companies, keep them happy, and grow with them as they grow. The more people a company hires, the more people use Slack, the more money Slack makes.

It’s so focused on customer retention over short-term revenue maximization that it actually scans how many people at a company actively use the product daily, and proactively refunds companies for people who have been inactive for a certain period of time.

Slack is horizontal software in an enterprise software market full of vertical players. Until recently, that meant that it built the chat layer across all of the vertical-specific things that a company does by integrating third-party software. As Ben Thompson pointed out, that focus on chat allows Slack to work not just between different teams in the same company, but across companies as well.

Connecting Slack’s Strategy

In July, Slack rolled out Slack Connect, which lets companies collaborate with each other via Slack. Say you’re working on a fundraise. Instead of emailing the internal team, external counsel, and banks, you can put everyone in one Slack workspace, set up channels for each piece of the project, and share documents seamlessly.

This is brilliant for the obvious reasons:

It makes the product go more viral.

It’s another step towards replacing email.

It allows Slack to build what Thompson called an “enterprise social network.”

But it’s brilliant for a less obvious reason that ties into Butterfield’s quote at the top of this section: “It’s always been the kind of thing that people don’t know they want, but once they have it, they can’t live without it.” Slack Connect uses the forward thinking companies that already use Slack as salespeople into the slower-moving, longer sale, Microsoft-using organizations, and it gives those companies a very specific reason to use Slack i.e. “If we want to win Stripe’s business, we’d better try this Slack thing.” It uses greed as a Trojan Horse through which it can prove Slack’s softer, ineffable benefits.

Phase I -- getting companies to use Slack Connect and invite their partners seems to be working.

Connects help Slack grow leads exponentially. Since introduction in Q2 2020, Slack Connect has grown at a 27% Compound Quarterly Growth Rate (CQGR), and connected endpoints, the number of companies connected to each workspace, is growing even faster. In Q2 2020, six companies connected to each workspace; a year later, 7.3 companies connect to each workspace. That means that there’s a double compounding happening as more companies set up Slack Connect workspaces and invite more partners into each. Slack doesn’t yet report conversion from an invite to a Slack Connect workspace into paying customer, but watch out for that number once they do -- it will mean that Slack is able to expand into new customers at a near-zero Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

Connect creates the Slack Flywheel:

Acquire forward-thinking, fast-growing companies,

Build core chat functionality that works so well that customers love the product,

Let companies set up integrations with all of the other software they already use, creating high switching costs,

Make Slack such a core part of the workflow that companies would rather work with outside partners via Slack than over email, creating network effects,

Get groups of companies to set up workflows and integrations that allow them to work more easily together, creating even higher switching costs,

By experiencing the product through Slack Connect, convince new customers to join Slack, love the product, set up workflows and integrations, and invite new companies to join them via Slack Connect, kicking the loop back off.

Slack Connect looks like a silly sideshow if you’re looking for reasons to be bearish on Slack, but it’s core to solving a challenge Slack knew it had since the beginning. In July 2013, two weeks before Slack’s preview release, Butterfield sent the team a memo later titled We Don’t Sell Saddles Here. In it, he talked about the challenge and opportunity incumbent in building a product in a new category. Because people didn’t have a frame of reference for the product, Slack needed to show them what the product could help them do and become instead of listing off a set of features. They needed to build a product that was “really fucking good,” listen to customers, and evolve in order to “build a customer base rather than gain market share.”

Slack Connect is the latest evolution of that thinking -- software that is so “fucking good” that companies convince their partners to use it, and help it build a compounding customer base.

That’s a lot of words, though. The beautiful thing about Slack is that the strategy shows up so clearly in the numbers.

# by the #’s

If you want to build a product so good that your customers will stick with you, grow with you, and acquire new customers for you, you do a couple of things: spend on research & development (R&D) and sales & marketing (S&M). That’s exactly what Slack has done, and it means that for now, unlike Zoom, Slack is unprofitable.

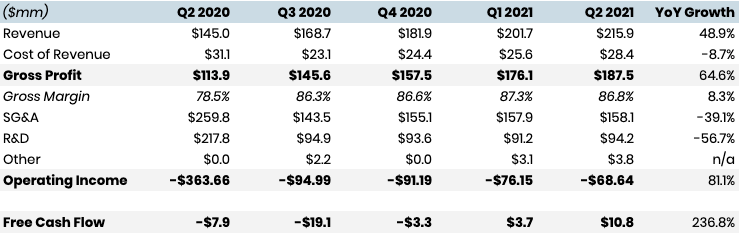

Slack has reported numbers as a public company for five quarters, meaning we can compare YoY numbers for the most recent quarter to its Q2 numbers a year ago.

In its first year public, Slack:

Grew revenue 49% from $145 million to $215.9 million

Decreased the cost of revenue from $31.1 million to $28.4 million as gross margins improved by 8.3% from 78.5% to 86.8%

Reduced SG&A, which includes S&M, by 39.1% (up 10% compared to the first non-IPO quarter)

Reduced spend on R&D by 56.7% (down 1% compared to the first non-IPO quarter)

Shrunk Operating Losses from $363.7 million to $68.6 million (or $26 million compared to first non-IPO quarter)

Improved Free Cash Flow by $18.7 million from -$7.9 million to $10.8 million.

That’s phenomenal performance, showing Slack’s ability to get operating leverage out of the business over time.

But since IPO, Slack’s stock price is down 33%, while the Nasdaq is up 47% and the BVP Emerging Cloud Index, which tracks public cloud Saas companies, is up a nice 69%. Maybe its numbers aren’t as good as its peers?

John Street Capital did an analysis on Slack’s performance versus the other 53 companies in the BVP Emerging Cloud Index on November 6th. (I’ve updated Slack’s rankings from JSC’s analysis based on new companies reporting and Slack’s updated price, pulling from BVP’s website.)

Even among some of the best performing stocks of the past year, Slack shines! Second best gross margin, eighth fastest growth rate, fifth best net dollar retention, and fifteenth best sales efficiency! It’s putting up top quartile numbers, but it’s trading like an average company based on multiples and a bottom quartile company based on performance.

This relative performance surprised even me, the biggest of Slack bulls. The narrative around Slack has been “If it can’t grow quickly and can’t generate a profit even during WFH, it’s a dog.” But it has grown faster than almost any SaaS company and has a clear path to profitability!

Slack’s currently trading at $25.75 with an Enterprise Value (EV) of $14.1 billion. If it traded at average BVP Emerging Cloud multiples, it would trade 20% higher, at $31.05 and a $17 billion EV. If it traded at top quartile multiples, as its numbers suggest it should, it would trade 75% higher, at $45.10 and a $24.7 billion EV. And if its stock had performed in line with top quartile YTD stock performance, it would be trading at $51.96 and a $28.4 billion EV, 102% higher than it is today.

It’s dragged down by three things:

A below average LTM Free Cash Flow Margin and unprofitability, which can be explained by its desire to pump money into S&M and R&D in order to acquire customers who it will retain and use to acquire new customers over time.

Investors fed up with underperformance who have given up on the stock.

A painfully lazy bear narrative that goes something like this:

The Bear Narrative

As much as we like to pretend that markets are fairly efficient, sometimes the market as a whole writes a story about a company and then looks for confirmatory evidence. That’s exactly what’s happening with Slack.

Maybe as a punishment for going the Direct Listing route instead of going through a traditional IPO, maybe because most banks are Microsoft Office users, maybe because Slack went public as a money-losing company right around the time that other unprofitable, unloved stocks like Uber and Lyft went public, or maybe because the street decided that it collectively just didn’t like the cut of Slack’s jib, the stock has been beaten down ever since it went public in June 2019.

The bear narrative around Slack focuses mainly on Microsoft Teams. The market views Teams, backed by superior distribution, a limitless balance sheet, and the fact that it’s bundled in free with Office365, as an existential threat to Slack’s growth.

Each and every time Teams releases new usage numbers, Slack drops. And Teams’ growth has been impressive. From 13 million Daily Active Users (DAUs) in July 2019, Teams recently reported 115 million DAUs in October.

Two things are important to keep in mind, though:

Office365, of which Teams is a part, has 258 million paid seats. Teams’ growth is just a function of getting its existing customers (which is a lot of customers) to use another one of its products.

Teams DAUs includes Skype and video conferencing, which are easier to grow quickly than the channel-based communications piece of the product. In fact, Teams highlights its video capabilities ahead of chat on its own website -- it’s there in plain sight, that it’s as much a Zoom competitor as a Slack competitor.

But the market doesn’t squabble over those details! Because the narrative around Slack is bearish, the market views anything Slack reports through shit-colored glasses.

It believes that Teams is an insurmountable threat, and it’s constantly on the lookout for confirmatory evidence.

When Slack reports Operating Losses, it views Slack as another unprofitable startup versus one investing in sales & marketing and research & development today to acquire customers it will retain forever.

When Slack reports 49% YoY revenue growth, it compares Slack to Zoom’s 355% growth instead of the rest of the BVP Emerging Cloud Index’s 27% median growth.

When Slack announces net dollar retention of 125% (down from 132% last quarter), it says, “Look, knew it. Slack must be losing customers to Teams!” instead, “Wow, that’s top quartile among emerging cloud companies! Of course it’s down a little, companies had to lay people off because of COVID. It’ll bounce back”

To be fair, Slack isn’t helping itself on the Teams narrative. While Butterfield talks about Teams as if it’s a non-issue and says that the company has never lost a customer to Microsoft, Slack brought an antitrust complaint against Microsoft in the EU in July, claiming that “Microsoft has illegally tied its Teams product into its market-dominant Office productivity suite, force installing it for millions, blocking its removal, and hiding the true cost to enterprise customers.”

Between July 21st, the day before the complaint, and August 11th, Slack dropped 15%. “We knew Teams was killing you,” the market gloated, “or else why would you have called your daddy?”

Of course Teams is a threat. It’s free, it comes pre-installed with Office and auto-opens when users open Office, and Microsoft has gotten its groove back under Satya Nadella.

But Mr. Market is dramatically overestimating the threat by missing a few important things with respect to Slack vs. Teams:

They Do Different Things. Teams is more about video than it is about chat. In fact, Teams limits the number of channels and employees that can be in any one workspace to a level that’s lower than most large companies need.

Companies Often Buy Both Slack and Teams. A gain for Teams isn’t necessarily a loss for Slack.Because Slack and Teams do different things, many companies big and small use both Slack and Teams. Ben Thompson said that he uses both, and Butterfield has said that many of Slack’s largest customers use both Slack and Teams.

Slack has Tripled Revenue Since Microsoft Released Teams. Microsoft released Teams in 2017, and Slack has tripled revenue, including strong growth in enterprise customers. This hints at the truth of points one and two.

Microsoft is Converting Its Own Users to Teams. As mentioned above, Teams’ DAUs are less than half of the total paid Office365 users.

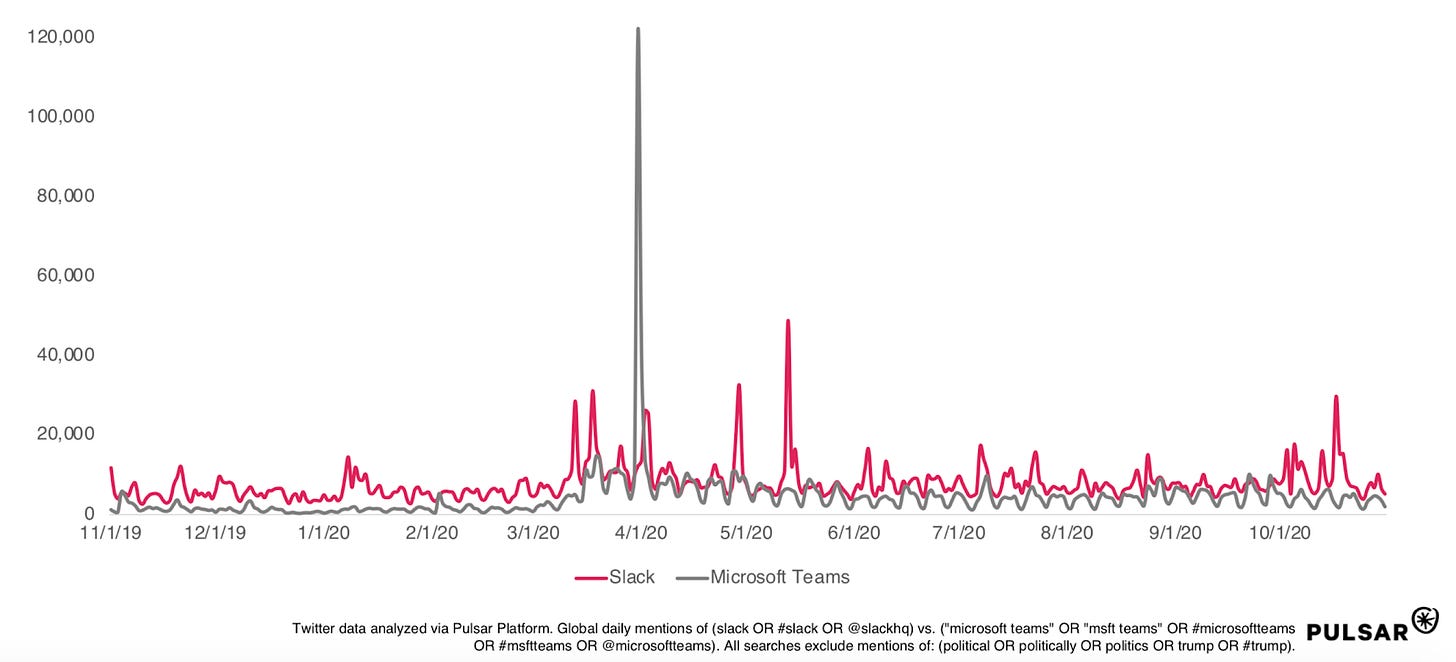

Data from Pulsar Platform supports that third point. More people talk about Slack more on Twitter than they talk about Microsoft Teams:

Despite more DAUs, Slack has more buzz. What’s more interesting, though, is who talks about Slack and Teams.

Pulsar is able to look at which types of people talk about each product based on their bios and their interactions on Twitter. Most of the people who talk about Microsoft Teams are Microsoft Loyalists, IT pros, and educators, while the people who talk about Slack are designers, product people, entrepreneurs, young professionals, software engineers, marketers, media pros, and hackers.

As a simple rule of thumb: the type of people who use PCs use Teams, and Apple users use Slack. Have you tried using Excel on a Mac?

Microsoft is winning its own users. 😴 Slack is winning startups and growth companies. 🚀

I could go on and on about why the Teams argument is bullshit, but Butterfield does a great job of picking it apart starting at 28:12 in this interview with the Verge. Give it a listen:

Two quotes summarize it well:

Or as Regina from Mean Girls’ would put it, “Why are you so obsessed with me?”

The market has bought Microsoft’s narrative hook line and sinker, and it’s wrong. There is nothing I like more than finding a bearish narrative that the market tells about a stock and that I think will break over time.

After Facebook IPO’d, the market didn’t think it could figure out mobile. I bought shares at $19 (of course, I’m an idiot and sold at $45).

In March, I wrote that Spotify would break out when it shifted more earshare to podcasts and reversed the narrative that the market told about its structurally poor margins. When it signed Joe Rogan a couple of months later, the stock popped and it hasn’t looked back.

In June, I wrote that Snap was coming out of the trough of disillusionment that it was in because the market didn’t think it could attract older users or monetize. It’s doubled since.

Slack is the next big narrative breaker. As its numbers continue to get better, the market will realize that Teams isn’t as big a threat as it thought. And the numbers are going to get much better, thanks to the Compounding Power of Young Users.

Ark Invest and The Compounding Power of Young Users

Cathie Wood built her fund, ARK Invest, on the belief that disruptive innovation is very inefficiently priced. On Invest Like the Best in 2018, she told Patrick O’Shaughnessy, “If you give us a long enough time frame, we will call ourselves a deep value manager, that’s how undervalued these innovation platforms are right now.”

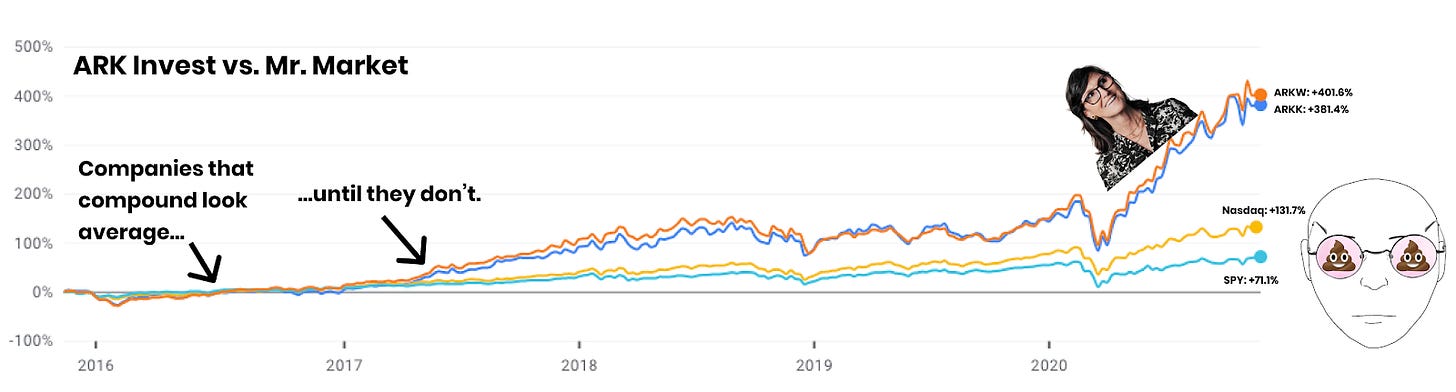

Why should you care? Because Cathie Wood has beaten the pants off of Mr. Market over the past five years.

ARK’s Innovation ETF and Next Generation Internet ETF have outperformed the NASDAQ by 3x and the S&P 500 by 5.5x over the past five years.

And while Mr. Market hates Slack, Cathie Wood loves it. Slack is the 9th largest holding in ARK’s flagship Innovation ETF ($388 million), the 11th largest in its Next Generation ETF ($97 million), and ARK even owns a little bit in its Fintech Innovation ETF ($13 million). One of the world’s best performing funds over the past five years owns nearly half a billion dollars worth of Slack.

So what does Cathie Wood understand that Mr. Market doesn’t? As O’Shaughnessy summarized in the interview, “Markets just tend to do a poor job extrapolating exponentials, they’re not good at pricing in exponential growth over a multi-year period.”

Wood put it even more succinctly: “The power of compounding over time is massive.”

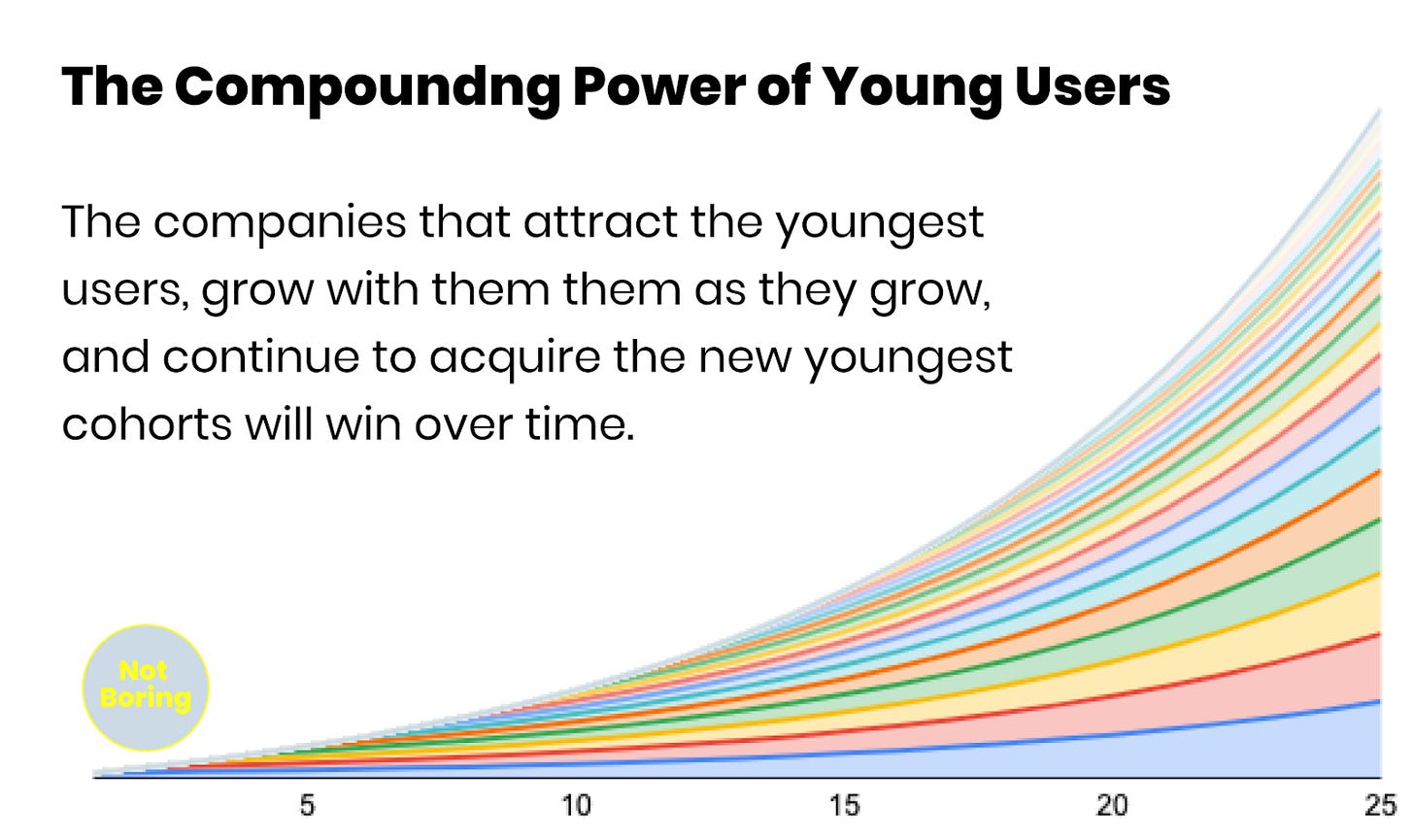

This is what makes Slack special and why I’m so bullish: Slack is a bet on the tech industry continuing to grow and compound over time. It generates revenue on a per seat basis, which means that its best play is to acquire customers that are going to add more seats over time.

To that end, Weng of Revealera, which provides alternative data for job openings and tech trends, put together an incredible analysis that confirms what I intuitively felt and what Pulsar picked up on: growing companies use Slack.

Weng highlighted three particularly relevant stats:

Slack Users Are Twice as Engineering Focused. Among companies that use Slack, 20% of job openings are for engineering roles. Only 11% of Teams companies open roles are for engineers. As I highlighted in the SkillMagic memo, according to LinkedIn, the five fastest-growing jobs in the world are engineering related.

The Biggest Startups Use Slack. Not only do startups use Slack generally, the biggest, most valuable startups in the world do. 65 of the 100 private companies by valuation according to CB Insights use Slack, including 8 of the top 10.

Slack is a Hireable Skill. Slack is mentioned in twice as many job openings as Teams, and the gap is widening. As the world moves remote, Slack is more than a tool, it’s a skill companies are hiring for.

Check out some of the companies that use Slack:

The only reason there aren’t more impressive logos in that image is because I had to stop. Every time I searched for a company, it hit, and then I saw two more multi-billion companies around the one I searched for. It even has MIT and Stanford so they get the next generation of unicorn founders when they’re young. In Q2 alone, it won Stripe, Shopify, Peloton, Unity, DoorDash, and Wayfair. Add in its June deal with Amazon, and it’s hard to imagine a portfolio better positioned to grow over the next decade.

In fact, Slack’s roster of customers really is like owning a portfolio: as they grow, Slack grows with them, with no additional acquisition marketing spend. This is the Compounding Power of Young Users, one of my favorite ways to think about companies like Snap and Stripe who take the longest view in the room.

Stealing customers from Microsoft would be great, but it’s not necessary. Slack just needs to acquire young and fast-growing users and make sure they stick around.

Stickiness, Net Dollar Retention, and Free Cash Flow

Riding the Compounding Power of Young Users is a two-step loop:

Acquire Young, Fast-Growing Users. As shown above, Slack destroys Teams here.

Retain Those Users and Grow With Them. This is all about stickiness and Net Dollar Retention.

Net Dollar Retention refers to how much existing customers spend over time, after accounting for churn. It is the most important metric to look at when considering a company’s ability to compound over time, and Slack is world-class. According to John Street Capital, the top quartile of the BVP Emerging Cloud Index averages 121% net dollar retention.

Slack, in its worst Net Dollar Retention quarter since going public, had 125% net dollar retention, which means that the group of customers that Slack had in Q2 last year spent 25% more on Slack this year. For Slack, net dollar retention over 100% comes three ways:

Customers add more of their existing employees to Slack.

Customers grow, hire new employees, and add them to Slack.

Customers upgrade from Standard ($6.67/seat/mo) to Pro ($12.50/seat/mo) or Enterprise (>$12.50/seat/mo).

As I covered in While Zoom Zooms, Slack Digs Moats:

Fader and McCarthy inferred (Part I and Part II) that only 10% of Slack customers churn within the first year, and that Slack retains a shocking 80% of its paying customers over 5 years. For comparison, according to Profitwell, the median monthly churn rate for SaaS businesses is 5-10%. Proportionally, most SaaS businesses lose as many customers in a month as Slack loses in a year.

For 100 companies that are using Slack today, 80 will still be using Slack in year five, and those 80 will spend 2.4x (100*1.25^4) as much as the original 100 did in year one.

That chart says more than meets the eye. On the surface, it shows that Slack will grow its revenue from its existing customers over time. One layer down, it shows why Slack is going to be a Free Cash Flow machine.

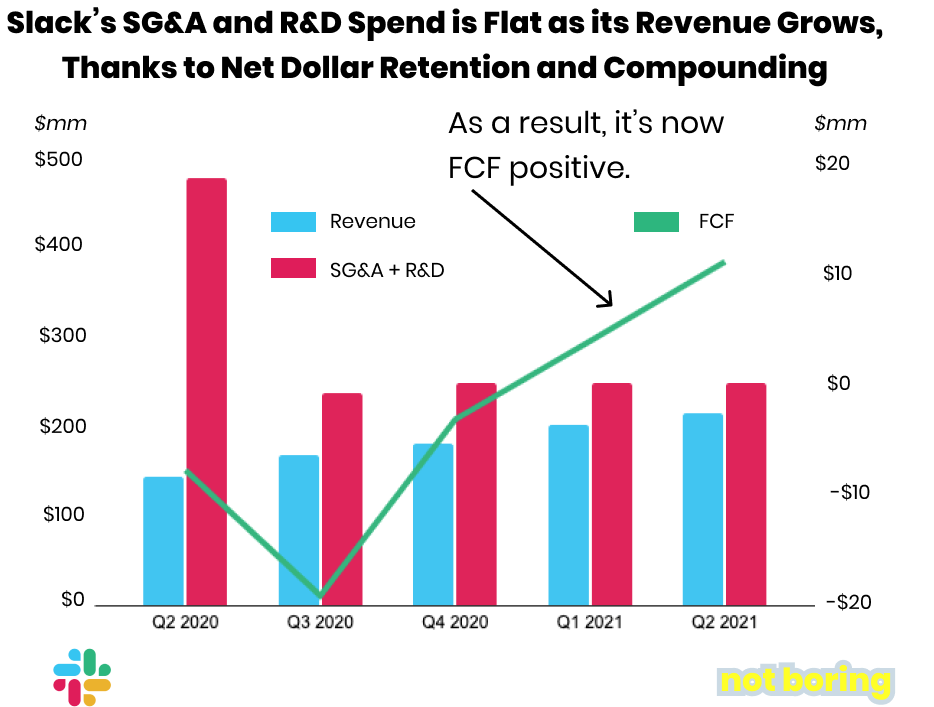

Currently, despite having the second best gross margins of any Emerging Cloud company, it has slightly negative Free Cash Flow (FCF), -1% over the last twelve months. It’s one of the bear’s biggest knocks, particularly when compared with Zoom and its 27% FCF margin. But look more closely, and see its Net Dollar Retention working its magic:

As revenue has grown, SG&A and R&D have stayed largely flat. That’s called operating leverage. And it means that over the past year, Slack went from an Operating Loss of $363.7 million and FCF of -$7.9 million in Q2 2020 to an Operating Loss of $68.6 million and positive FCF of $10.8 million in Q2 2021, the most recent quarter.

Put another way, unless it makes a conscious decision to spend more on Sales & Marketing or R&D in the future, the gains from compounding revenue growth are going to drop straight to the bottom line.

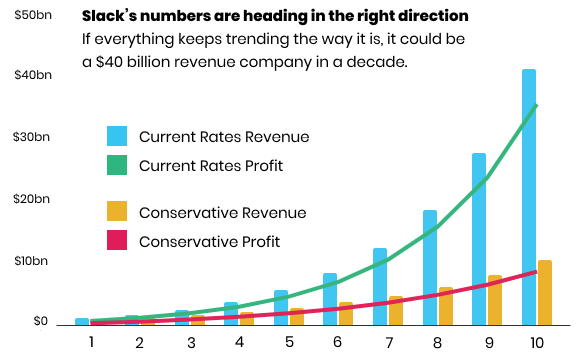

If it keeps up its revenue growth and gross margins while keeping SG&A and R&D relatively flat, in five years, it will be generating over $4 billion in profit on $5 billion in revenue. In another five years, that’s $35 billion in profit on $41 billion in revenue. More conservatively, if it grows revenue by a more modest 30%, keeps gross margins stable, and doubles spend on SG&A and R&D, it will generate $2.7 billion of profit on $3.7 billion in revenue in five years and $8.7 billion of profit on $10.6 billion of revenue in a decade.

At the BVP Index average ~20x revenue multiple, that means an EV of $70-100 billion in five years and $200-800 billion in a decade. Compounding comes at you fast.

That’s the magic of compounding, and it’s enabled by the two things Slack does best: acquiring fast-growing users and getting them to stick around. Getting that for $14 billion today seems like a steal.

The biggest threat to that growth isn’t Microsoft’s dinosaur ass. It’s Slack’s inability to continue feeding the next generation of young, fast-growing companies into the loop.

The Real Bear Case

While I don’t take Wall Street’s bearishness on Slack very seriously because it’s based on a lazy thesis followed up with confirmation bias, I take Kevin Kwok very seriously.

In The Arc of Collaboration, Kwok argued that instead of becoming the central nervous system for collaborative productivity, Slack is actually the “911 for whatever isn’t possible natively in a company’s productivity apps.”

By that, he means that as more software like Figma, GitHub, Jam, and Salesforce allows people to communicate and collaborate directly within the app they’re using to get work done, Slack is a mere backup plan. If a designer and a PM can chat within Figma or a PM and an engineer can collaborate on the website within Jam, Slack becomes the place where people go when their regular processes break. In that world, it’s not the company’s central nervous system, and loses its crucial spot in the value chain.

There’s still room for a “meta-coordination layer” in a world in which collaborative productivity tools eat each piece of the work companies do, but Kwok doesn’t think it’s Slack, at least in its current form. “If you have to switch out of a product to use Slack,” he argues, “then it is not the layer tying them altogether. Instead, the layer needs to exist a layer above.”

Kwok used Discord, which is a meta-layer of text, audio, and video chat that exists a layer above all games, as the best analog. At the time he wrote the piece in August 2019, Discord was purely gaming focused. But during quarantine, Discord has repositioned itself as a more general “place to talk.”

Discord isn’t yet positioning itself as a workplace collaboration tool, and there are all sorts of integrations and gnarly compliance work it would need to do to get there, but Discord, or something like it, is a bigger threat to Slack than Microsoft Teams is. If Slack’s ability to grow into its potential is predicated on its ability to attract the youngest, fastest-growing users and grow with them, then Discord, which targets younger users than Slack does, could cut off the loop that fuels Slack’s growth.

Indeed, according to Pulsar, the entrepreneurs and designers who are Slack’s most vocal users are beginning to talk about Discord, too.

So what should Slack do? The easy answer would be, “buy it,” but at the $3.5 billion valuation it received in June and Slack’s depressed stock price, it would have to spend over a quarter of the company to acquire Discord. Plus, Butterfield has said that the two companies do very different things, and don’t want to do what the other does. And yet, buying Discord might be the smartest move Slack can make to protect its future and grow the customer base it’s able to serve. But that’s a topic for a different essay.

For now, Slack needs to take Discord seriously and steal its tricks in order to truly become the meta-layer that enhances peoples’ ability to do their best work instead of the distraction that it can often become. It should do three things to improve its customers’ ability to do work and dig a deeper moat to prepare for the inevitability that Discord or a similar work-focused product comes after it.

First, it should consider opening up its API to power the next wave of collaborative productivity tools. Call is Slack-as-a-Service (“SlaaS”). Imagine Airtable or Webflow with Slack voice calls and chat built in, for example. Teams could chat directly within the software while working in it, and even employees who aren’t in the software could participate in the conversation from inside of the Slack app, just like Discord users can be a part of the conversation with their friends whether or not they’re playing the game.

Extending its position as the hub for thousands of integrations, it might even serve as the pipe that allows products that integrate with Slack to integrate with the products that embed Slack-as-a-Service. So if Loom integrates with Slack, and Airtable uses Slack-as-a-Service, Loom could integrate with Airtable via Slack.

Second, like Tencent, it should double down on leveraging its position in the value chain to identify the workplace collaboration and productivity tools that its customers love the most, and provide capital via an expanded Slack Fund and traffic via its app directory and integrations.

Finally, it should double and triple down on Slack Connect to acquire more customers more quickly and efficiently, and create network effects that new entrants can’t compete with. If Slack can serve as both the connective tissue among companies, and between companies and the products that they use, all within their existing workflows, it will be in a position to compound its advantage for years to come.

(Update: Butterfield went on 20 Minute VC with Harry Stebbings this morning (!!) and said that Slack is working on Huddles, always-on audio channels (like Discord!), Stories (like Instagram), and allowing companies to host code within Slack. He said, “Slack five years from now will function much more like the lightweight fabric for systems integration that we’ve always believed it can be on the platform side, and will come to encompass most of the people you communicate most frequently with even if they’re outside of your organization, because that’s something that’s exploding right now.” Slack is executing on points one and three, smart.)

Picking Up the Slack

Look, I’ve been wrong on Slack so far. I have no idea if I’m right now, and if I am right, I don’t know if that will express itself in Slack’s stock price in the next week, the next month, or even the next year. Compounding is slow before it gets fast.

What’s worse, even though Slack has not benefited from the WFH stock rally to the same extent that Zoom or most other cloud-based SaaS companies have, it’s still vulnerable to drop with those stocks on any news about a potential vaccine or reopening.

But the fundamentals are there. Slack doesn’t care if you’re working from home, working from an office, or doing some combination of both. Unlike Zoom, Slack is just as useful in any of those scenarios. Slack’s numbers are good, improving, and underappreciated. The Teams narrative is loud, overdone, and puts shit-colored glasses on all of the good things that Slack is doing.

I’m taking every opportunity I can to pick up more Slack, because once the narrative shifts, I think it’s going to take its rightful place amongst the most valuable SaaS companies in the world.

If you’ve read this far, here’s a bonus: I teamed up with Switchboard to give $500 to charity:water and get you access to an incredible event.

Switchboard makes it possible to learn with the world’s leading experts while doing good.

They are hosting a closed door chat with Ryan Graves on Giving Tuesday (12/1) where attendee proceeds support Ryan’s charity of choice, charity:water, a non-profit that directly funds water projects that impact health, education, and women empowerment outcomes.

To celebrate Giving Tuesday, Switchboard is matching the first $5,000 in raised funding.

I’m covering the 10 tickets for Not Boring readers. Mention NotBoring in the Q&A submission form, and if you’re one of the first 10, your $50 ticket is on me.

Social trends data was brought to you by Pulsar, the Official Audience Intelligence Sponsor of Not Boring. Big thanks to Marc and the Pulsar team for helping pull signal from the noise.

Thanks to Dan and Brett for your feedback and input.

Thanks for listening, and see you Thursday,

Packy