Ramp's Double-Unicorn Rounds: Behind the Scenes

What's it like to raise at $1.1 and $1.6 billion valuations from D1 and Stripe within a day

Welcome to the 1,239 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Thursday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 43,175 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today's Not Boring is brought to you by ... The On Deck Investing Fellowship

Software is eating the markets, and more people are investing than ever before. That’s a great thing overall, but in this environment, it can be hard to separate the signal from the noise.

Determining your ideal strategy requires understanding risk, psychology, and your own preferences. Investing is simple, but not easy. There are core components of the investing process that you can learn to give yourself a better shot at building long-term wealth. They should teach this stuff in high school, but they don’t.

Enter On Deck Investing (ODI)!

On Deck Investing is a ten-week, remote program for investors who want to deepen their knowledge of public markets, sharpen their investor psychology, and accumulate practical tools for sustainable long-term wealth creation alongside a network of thoughtful peers. As an On Deck investor and alum, I know it will be high-quality.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday!

If you’re interested in startups and venture capital, today’s post might be more lesson-packed than any I’ve written. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at one of the world’s fastest-growing startups, how big funding rounds come together, why valuations make more sense than it seems in headlines, and how Stripe invests.

I’ve told you that I’m an optimist, and that I’m going to be effusive about my favorite companies. That’s certainly going to happen in this piece. The idea here isn’t to pump up Ramp -- they don’t really need my help -- but to give you a glimpse at what makes a truly exceptional company truly exceptional, even in its earliest days. I hope it’s instructive for people building companies, and investors thinking about where to put their time, attention, and money.

Disclosure: This is not a sponsored piece, but I am a small investor in Ramp (this round) and they previously sponsored.

Let’s get to it.

Ramp’s Double-Unicorn Rounds: Behind the Scenes

^^ Click this to just read the whole thing online

Ramp’s Double-Unicorn Rounds: Behind the Scenes

Ramp is the fastest company to cross the $1 billion valuation mark in New York City history. And it did it twice, within a day.

Stripe just valued the two-year-old company at $1.6 billion, right after D1 Capital and other investors valued it at $1.1 billion. All in, Ramp has raised over $300 million. It has never made a fundraising deck.

Rounds like the ones Ramp just raised don’t come together often. Peeks behind the curtain when they do are even more rare. Ramp’s co-founders, Eric Glyman and Karim Atiyeh, agreed to share how it all went down. They know that the whole thing is a little crazy, and that a double-round like the one they just put together is uncommon. That’s what makes it worth telling.

Headlines like “Two-year-old company raises two unicorn rounds within day” leave you with a lot of questions. What does it feel like to be at the center of a feeding frenzy? What metrics do you need to get a $1 billion valuation two years in? How do you decide which investors to bring onto your cap table? Why two rounds? Luckily, we have answers.

Today, we’ll cover:

Has Venture Capital Lost Its Mind?

Ramp’s Ramp: Trajectory and Velocity

Behind the Scenes of Ramp’s Double-Round

Round Construction: Don’t Optimize for Price

Stripe Invests in Ramp

What’s Next?

This is a story about people, trajectory, and velocity, played out over a long time horizon. It’s about why it makes sense for investors to pay up for the best companies, and why the best companies care less about price.

The market seems frothy, but in many cases, like this one, it’s more thoughtful and rational than it looks.

Has Venture Capital Lost Its Mind?

Let’s start with the facts:

In December, Ramp, the NYC-based spend management platform and corporate card company, announced a $30 million round led by D1 Capital Partners and Coatue Management. I wrote about it here.

In February, it announced $150M in debt financing from Goldman Sachs.

Today, Ramp is announcing (themselves) that they’ve raised $115 million in two back-to-back rounds:

One, a $65 million round led by D1 Capital Partners, with participation from Goldman Sachs, Founders Fund, Coatue Management, Thrive Capital, Redpoint Ventures, Box Group, Neo, Contrary Capital, and a roster of angels valuing the company at $1.1 billion.

The second, a $50 million round led by Not Boring favorite Stripe at a $1.6 billion valuation.

The gut and easy reaction to that is, “Wow, investors have really lost their minds. This is just a sign of the times -- low interest rates during a pandemic -- and it’s not going to end well.”

Yes, interest rates are low. Everyone is raising a mega fund. SoftBank was mocked, but it was just the beginning. Tiger Global just closed a $6.7 billion venture fund. Crossover funds like Coatue, D1, Altimeter, and Greenoaks are going earlier and earlier. Startups themselves are investing in other startups, none more than Stripe. There is more demand (investment dollars) chasing supply (fast-growing startups) than ever.

But if you’ve been reading Not Boring, you know I don’t think that’s the whole story. None of these funds are dumb. They’re not trying to light their LPs’ money on fire. They’ve seen that tech companies with the right stuff can get faster and bigger than ever before.

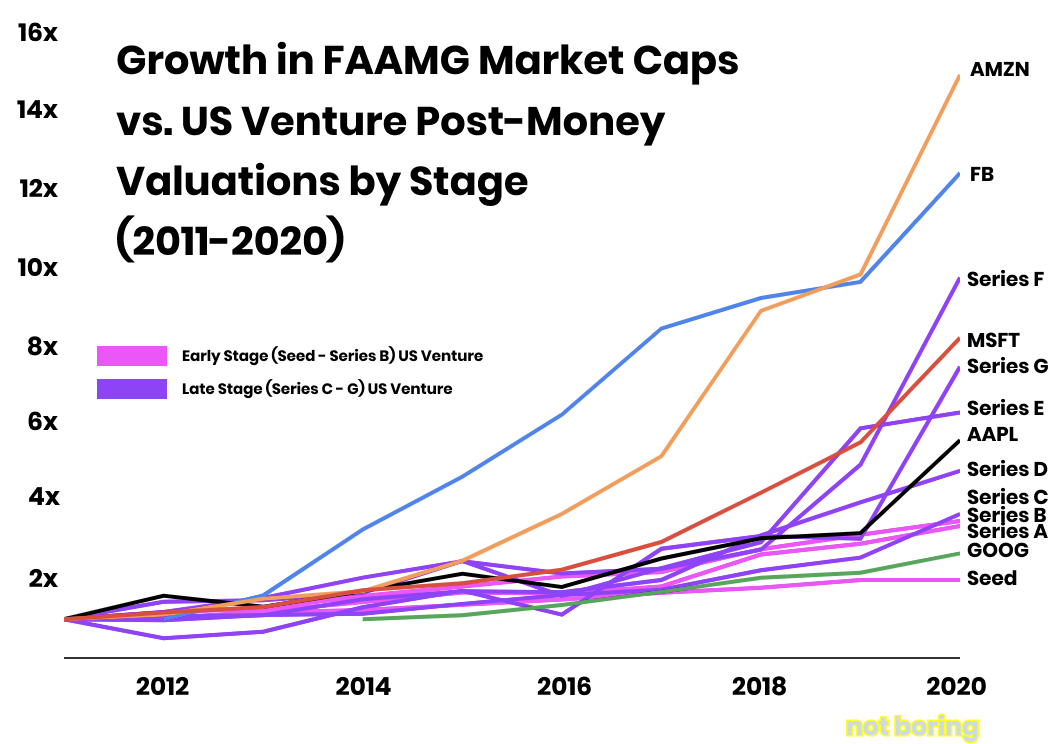

In Dreams All the Way Up, I wrote that valuations for the best early stage tech companies might actually be low if you look at startup valuations as a probability that the companies become as big as the biggest tech companies, or at least the biggest companies in their categories. If Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are fairly valued, and their market caps have grown faster than startup valuations over the past decade, then either startups have a lower probability of becoming as big as the biggest companies, or they’re undervalued.

That’s a numbers-based argument, but there’s a common sense reason that the best startups today should be worth more than the best startups a few years ago were at the same age and stage. As Eric told me, “There have never been so many people in and around this ecosystem who get what scale looks like, and have been part of a ride on the way up.”

Plus, new startups have advantages over startups built just a few years ago:

Examples of successful exits show that it can be done.

Investors have seen those exits and are willing to make bets earlier.

Talent with experience building products at scale.

Tools that make it easier to build great products more quickly.

Today, a top engineering team can take so much good software off the shelf that development timelines have been dramatically compressed. Logan Bartlett, a VC at Redpoint, guessed that just a decade ago, it would have taken seven or eight years for even a great company to build what Ramp did in two. And Ramp did it with a team of less than 100 people. Of course Ramp is worth more, faster today than a similar company would have been before.

Companies are getting really big, really fast, and that’s altering the markets. Let’s say, with all those advantages, that if it would have taken Company A four years to get to $100 million in revenue five years ago, it takes a similar company, Company B, three years to get there today.

That seems minor, but it’s a completely different trajectory: Company A is growing at 115% per year and Company B is growing at 216% per year. Over time, that difference gets dramatic.

By each company’s fifth year, Company A, the older one, will be at $215 million in annual revenue. Company B will be at $1 billion. Obviously, a lot of things can change: growth can slow, an early market may get saturated, customers can churn. But it illustrates that trajectory really matters, and it matters more than you can easily comprehend.

Company B shouldn’t just fetch the same valuation as Company A when they’re both at $100 million in revenue; it should be worth more, because it’s growing so much faster. Having seen similar scenarios play out successfully, investors now have a better sense for the impact of compounding at hypergrowth companies, and are more willing to underwrite against it. They’re willing to pay more, earlier, because they trust the trajectory.

Lest you think I’m a valuation maximalist, my willingness to apply this logic only extends to the very best companies, the ones that are actually on that trajectory. I think Clubhouse’s rumored $4 billion valuation pre-revenue is fucking bonkers, and even though I love Stripe, I do not understand its investments in Fast.

For companies like Ramp, though, and there aren’t many, trajectory and velocity are driving high valuations that may look cheap in even a few months.

Ramp’s Ramp: Velocity and Trajectory

I wrote Ramp: The Card-Sized Finance Team in December, and if you’re interested in more of the Ramp story and strategy, you should check it out. For this piece, I want to highlight the things about Ramp that are relevant to this double-round coming together in the way it did: velocity and trajectory. They’re Ramp’s Ramp.

Ramp can move faster than other payments companies because of how it’s built and what it’s building: it’s an engineering and product-driven company slash corporate card (and not the other way around).

Ramp’s corporate card is where it makes most of its money today, but really, it’s just a Trojan Horse into the CFO Suite.

Ramp’s goal isn’t to make the world’s best corporate card; it wants to help companies spend less money. Seriously, this is what they’ve been telling investors, too, from the beginning. Here’s an email from Karim to Keith Rabois and Delian Asparouhov at Founders Fund in May 2019.

Ramp’s strategy is to align itself with customers, decrease spend, and build healthier businesses that can reinvest in growth. It’s the long-game, but it’s already working. Ramp is in the driver’s seat to own spend management for mid-market companies, and from there, to move upmarket. After wedging into companies with the corporate card, Ramp gives them new software products to help control and manage spend at an astonishing rate.

You need both -- the card and the software -- to win.

Companies that stay software-only, like Expensify, are getting picked off by companies like Ramp that turn its whole business into a free feature, while companies that focused too heavily on corporate card sales and marketing at the expense of product, like Brex, were caught flat-footed as the card itself became table stakes.

Software companies are just faster, and that’s a major advantage in a massive market with essentially uncapped upside. In a market like that, winning is all about trajectory and velocity. New features help acquire new customers, and retain and delight existing ones by saving them money.

How does Ramp ship so fast? People.

When Karim, Eric, and I had our first conversation about this piece, Karim highlighted how they think about hiring: “We hire people for potential and growth trajectory, slope over intercept. We make bets on people. The goal is not zero defects, but 10x potential.”

The team today, at 85 employees, is absurdly talented. One-third of the team are former founders, and at least five people on the team graduated with perfect GPAs from MIT, Stanford, Harvard, and other top schools. The team also includes a few dropouts. Overall, the team skews heavily towards engineering and design. That, plus conversation with angels and customers, has allowed them to ship at an unbelievable cadence.

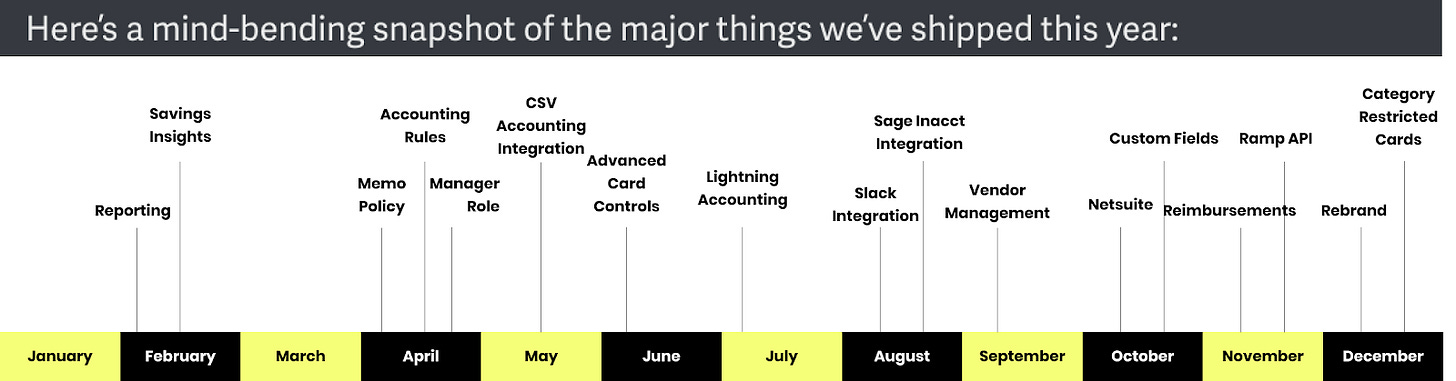

In an internal email, “2020 Product Recap,” Ramp’s Head of Product, Geoff Charles, wrote (and I beautified using my Figma skills):

And Ramp just keeps building. Since that December email, Ramp has introduced custom spend controls, more accounting automations, multiple expense policies (i.e. an exec needs a receipt for anything over $100, an intern needs a receipt for anything over $25), more savings insights, more benchmarking, and an integration with 1Password. They’re not slowing down.

Talent density and product velocity are the difference between excellent and world class. Corporate card competitor Brex has an excellent 4.6 star average rating on G2. Ramp has a perfect 5.0.

Not a single one of Ramp’s 62 reviews rated it less than a perfect 5.0. That’s absurd.

Ramp’s strategy depends on that customer love. Happy customers tell other customers. They tell investors. And they’re not just willing but eager to use every new product and feature that Ramp rolls out. When I last wrote about Ramp, I highlighted Ramp Reimbursements, the company’s Expensify-killer. Who among us doesn’t hate using Expensify?

Since then, over the past four months, more than 90% of customers adopted Ramp as a comprehensive spend management platform, replacing Expensify, Concur or manual solutions. People stopped spending money on whole, expensive products and switched over to Ramp. As Ramp adds more features that outcompete entire companies’ products, and as those products save customers more money, the case for Ramp grows stronger.

Ramp makes money on interchange. Like a normal credit card company, it takes a 1.5%-2.5% fee on transactions (paid by merchants/card networks) when customers spend using the card. Unlike a normal credit card company, it doesn’t reward users with points; it rewards them with better software. Better software drives more usage, which drives more revenue, which drives better software, and so on. The faster the flywheel turns, the further ahead Ramp pulls.

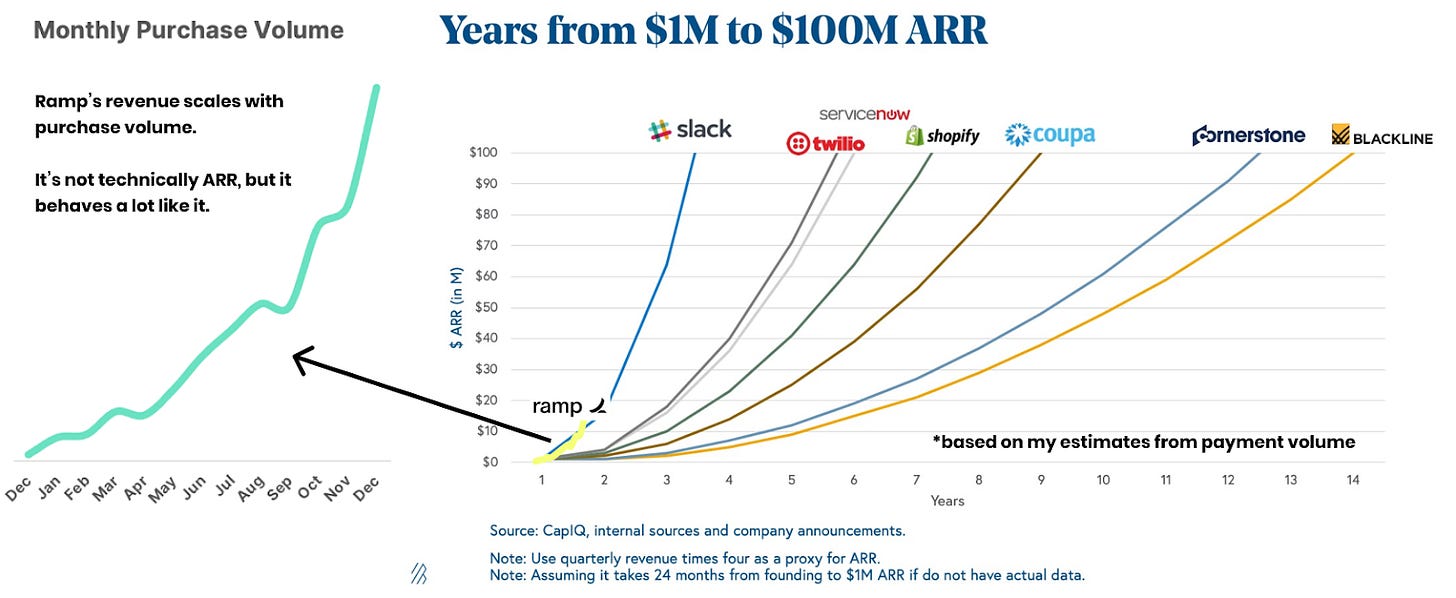

That velocity is already showing up in Ramp’s total purchase volume (TPV) and revenue numbers today. The company is aptly named. Look at this ramp up:

Ramp grew monthly purchase volume 60x in 2020, and 47% MoM in December alone. That means that customers spent 60x more on Ramp cards in December than they did in January, which roughly translates to 60x the revenue. Those kinds of numbers bring the investors to the yard.

Behind the Scenes of Ramp’s Double-Round

This is where this piece goes from analysis to full behind the scenes. It’s very unusual to be able to pull back the curtain like this, to get the oral history of a typically secretive process in real-time, but Eric and Karim were down to share how it all went down.

I should have known that Ramp was going to raise again soon when, after writing about the company in December, I got a text from my friend Logan at Redpoint: “How well do you know Eric from Ramp? I’m obsessed with them. Like legit am going to do some crazy shit to get involved.”

And that was before it really started heating up. Three things happened between the time Ramp announced a $30 million round in mid-December and the double-round that ultimately came together in February: revenue growth, Goldman, and the December 2020 Investor Update.

First, revenue growth. Ramp’s revenue grew a combined 68% in December and January. Growth accelerates everything. It’s easy to talk about the market being frothy because rounds are coming together so soon after previous ones close, but the growth Ramp saw between November and January would be a strong full year growth rate for a lot of companies. When growth is faster, it’s natural that funding rounds come faster.

Second, in February, Ramp announced that it raised $150 million in debt financing from Goldman Sachs. That facility made Ramp’s balance sheet much more scalable. More balance sheet means more credit which means both more transaction fees, and more customers to whom it can eventually sell software. Plus, the Goldman Sachs stamp of approval means something.

Third, the email: December 2020 Investor Update and Ask, sent on January 12th. This is what really kicked things off. Put yourself in the investors’ shoes here. Imagine you put some money into a company, and people keep saying great things about it, and it recently raised, and then you get an email that starts out like this:

The email induced animal spirits, the sister of “deal heat,” the momentum that builds in a round when a bunch of investors get interested at the same time. Often, founders try to manufacture it by bunching investor meetings together and setting artificial deadlines. Eric and Karim have been playing the long game.

After they sold their first company, Paribus, they invested in and advised over 30 companies, many of whom became early sounding boards and customers.

They seeded the money for Ramp, and then brought in Delian Asparouhov and Keith Rabois at Founders Fund as the first outside investors (that round was scooped by the same Information reporter as this one).

They also brought in a host of founders, CEOs, CFOs, and product leaders as angel investors. Those angels gave product feedback, became customers, and introduced Ramp to customers. They also talked. That was intentional.

When Ramp sent the December update, they sent it to a lot of people. Angels aren’t competing to lead the round, they have nothing to lose from talking about Ramp’s progress, and they have social capital to gain. That was intentional, it helped create a buzz.

This is where the animal spirits really start to kick in. People got the sense that something special was happening, and the vibe was out that a round might come together quickly.

Eric told me that after the email went out, things started picking up almost immediately. Phone calls and texts started coming in more frequently. People seemed unusually eager to grab a virtual coffee or to be helpful in any way. Luckily, the team recorded it and shared with me:

Call it animal spirits. Call it deal heat. Whatever you call it, it was on. Turns out, a lot of investors were willing to “legit do crazy shit to get involved.”

Side Note: Logan did end up doing some crazy shit to get Redpoint involved. He sent Ramp a 130-page deck on the product compared to competitors, customer surveys, and strategy. He made over a dozen introductions to top sales and marketing leaders in four weeks. He flipped the “Let me know how I can be helpful” trope into “Let me show how I can be helpful.” While Redpoint didn’t get the lead, it got a meaningful allocation in the round. When I asked him what he loved about the company (after I had already written the last section) he said: “Velocity.” I don’t think Ramp’s heard the last of Logan.

While there was a lot of interest, there was only a small group of serious contenders for the lead spot, including Redpoint and many of Ramp’s existing investors.

D1 Capital, which co-led Ramp’s $30 million last round, ended up winning. They had the first conversation about leading a new round in early/mid January, aligned on terms on January 29th, and had a signed term sheet by February 5th.

The deal stayed quiet for nearly two months, and almost made it to the official announcement day, when Eric and Karim got this email from a reporter at The Information:

The Information published the story later that afternoon.

Leaks happen, and no one’s going to feel bad for a two-year-old company that just raised $115 million, but it also kind of sucks. That’s big news for the people involved -- Ramp’s team and the investors who competed to get in the deal -- and a headline by a reporter you haven’t spoken with on a random Monday drop is a pretty unceremonious way for the world to find out.

But the news is one thing. The Information got the what, but not the why or how.

Why did Ramp ultimately choose to go with an existing partner instead of bringing in someone new at a much higher price? When you have that much interest at such dizzying valuations, what do you do? How do you decide whose money to take?

Round Construction: Don’t Optimize for Price

Picking among a group of world-class investors, all of whom are willing to outbid and out-crazy-shit each other to give you money, is a champagne challenge. But it’s a challenge nonetheless. Eric and Karim described it as a “weird dance,” and view cap table allocation (which investors you choose and how much they invest) as a strategy and a means to compete.

Here’s their first tip: picking the highest price is almost always the wrong answer.

Over the first months of the year, as the energy grew and the animals got more spirited, rumors began to swirl that investors were willing to go up to valuations as high as $2 billion+. Instead of pursuing those, Ramp chose to sell 6% of the company in a D1 led round for $65 million, valuing the company meaningfully below what the high end of the market was seemingly willing to pay.

That’s a little counterintuitive. Picking the option that allows you to sell the smallest piece of the company for the most cash seems like the right move on paper. But it’s usually not, not in the long-run.

Not raising at the highest prices leaves room for three important things:

Operating Error. If you don’t set unattainable expectations, you can make some mistakes along the way and everyone comes out fine. You also don’t look like a pig.

Excess Demand. If you don’t sell the max amount you’re comfortable with at the time, there’s room to add aligned investors as opportunities arise. (See Stripe below)

Employee and Investor Upside. More upside attracts better employees and investors, and makes them happier, which leads to better results over time.

Not optimizing for price in the short-term means that you can optimize for terminal value, the only number that really matters.

Eric acknowledged that they feel really fortunate to be in a position to be able to do right by people and that Ramp’s situation is unique, but he quickly added:

At another level, it's not. It's an iterative thing, hopefully you play out over many years and decades. Because of availability of capital, the constrained thing is people. If you can unlock helping people achieve their goals, that speeds up the rest -- talent, excitement, and luck -- you maximize the probability of things going right over time.

Maybe because they’ve been through it before and have an exit under their belt, Eric and Karim are taking a long view with Ramp. Very few companies can pull that off, but one in particular comes to mind… Stripe. In a 2016 interview with Ezra Klein, Patrick Collison said:

There’s something quite deep about the notion of using time horizons as a competitive advantage, in that you’re simply willing to wait longer than other people and you have an organization that is thusly oriented.

Stripe and Ramp understand the seemingly magical power of combining high velocity and trajectory, positive sum interactions, and long time horizons better than almost anyone. That’s not the only thing they have in common.

Stripe Invests in Ramp

At the same time the D1 round was coming to a close, Stripe was also talking to Ramp about a separate round at a higher valuation. Stripe invested $50 million at a $1.6 billion valuation, a nice quick markup for the investors in the D1 round.

On the surface, the benefits are obvious.

Ramp gets to use what it sees as the best-in-class issuing platform (Stripe) and benefit from the velocity of Stripe's ongoing development. “Using Stripe Issuing will in itself be a competitive advantage," explained Eric. And an investment from Stripe, particularly since Stripe has its own Corporate Card, is a little like the fintech equivalent of a knighting.

Given the advantages Stripe gives Ramp, the 50% markup is a head scratcher. It makes more sense when you understand what Stripe is building, and how Ramp fits in.

What is Stripe building?

Stripe’s mission is to increase the GDP of the internet. At its core, it does that by building payments infrastructure for the internet. Its APIs are the highway on top of which money zips around the world.

In August’s Stripe: The Internet’s Most Undervalued Company, I wrote:

Longer-term, Stripe is building not just the infrastructure on top of which money moves -- what it calls the Global Payments and Treasury Network -- and the platform on top of which companies are built. It is moving to own every piece of the journey.

In December, Ben Thompson wrote Stripe: Platform of Platforms after Stripe announced Treasury and a deeper partnership with Shopify. That announcement, and Thompson’s piece, helped bring Stripe’s strategy into tighter focus: it’s the platform on top of which other platforms build.

Stripe builds the back-end, its customers build the front end. Stripe builds APIs that anyone can use, its customers use them to build tailored experiences for a particular target audience. Stripe’s products proliferate, and its business grows, when it makes it easy for all sorts of online businesses -- those serving merchants and barbers and writers and CFOs -- to offer their customers better, more reliable, payments experiences, and increasingly, financial products.

Stripe is the highway, and its customers are the last mile.

When those customers are last-mile fintech startups, Stripe might even invest.

How does Stripe invest?

I think Stripe is the closest thing the United States tech ecosystem has to Tencent.

Tencent invests capital in startups, and then sends them traffic. It’s not afraid to admit when it’s been beat, and invest in companies building a better version of something it tried to build itself.

Stripe’s investment strategy seems to be similar. It launched corporate cards in 2019, but corporate cards aren’t the company’s core focus, let alone spend management and all of the adjacent CFO-suite tooling that Ramp builds. So instead of diverting focus from the core, Stripe can invest in companies whose products orbit its core, providing capital, software, and potentially even traffic.

As its own valuation has climbed, Stripe has ramped up (pun intended) its investing in 2021. According to Crunchbase, it made seven investments in Q1 of 2021, just one shy of the eight investments it made all of last year.

All of its investments are focused on increasing the GDP of the internet. Its biggest investments are in fintech companies like Monzo, Check, and Step that provide last-mile financial services instead of core payments infrastructure (well, and Fast, which 🤷🏻♂️ .) Kind of like Ramp…

Why did Stripe invest in Ramp?

Stripe and Ramp have known each other for a while. In 2019, Ramp evaluated working with Stripe Issuing when it was just getting started, and even though they went with Marqeta, the two teams stayed close. As the D1 deal was coming together, D1 encouraged Ramp to reach out to Stripe. Since Ramp didn’t take the highest price for the D1 round, and sold only 6% of the business, there was room left for Stripe to invest as much as it might like, and for Ramp to sell more of the company without a painful amount of dilution.

But why did Stripe invest? Eric and Karim were open books about the entire process, except when it came to Stripe’s thinking. So I’ll have to speculate here, and I think I see why it makes sense:

Stripe and Ramp are both similar and different enough in just the right ways.

Stripe’s investors and partners include Founders Fund, D1 Capital, Redpoint, Thrive, Goldman Sachs, Coatue, and others. There’s a lot of overlap on the cap table.

Both companies succeed when more economic activity happens online.

Stripe was a model for Ramp in thinking about building a nexus of talent in a company since the earliest days, and both companies are very focused on hiring the highest potential engineers and designers in the world. These are similar cultures.

Ramp just hired its Chief Business Officer, Colin Kennedy, from Stripe, where he was the Global Head of Partnerships.

Both companies have very nice co-founders who play the long game.

Both are in the top 0.1% of companies when it comes to product velocity. When I first called that Stripe would be worth more than Goldman in September 2019, I highlighted Stripe’s product velocity as a reason:

But the two companies are just different enough.

Stripe builds infrastructure, Ramp builds customer-facing software.

Stripe offers an Issuing API that businesses like Ramp can use to let their customers spin up virtual and physical cards.

Stripe doesn’t have a big customer support or sales team. They’re an enabler.

Stripe serves companies that build software. Ramp is a software company that serves finance teams, and puts all of its energy into solving for that particular audience.

Stripe is the highway, Ramp is the last-mile.

The two businesses look competitive, but they’re complementary.

When I wrote about Stripe in August, I predicted it might, “Augment or replace large portions of finance teams with software, improving profits for its businesses.” It wants online businesses to survive and thrive, and building tools that help finance teams increase profits seemed like a logical extension. I was right on the what, wrong on the how.

At the time, I wasn’t as familiar with Ramp, but that’s exactly what Ramp does: augments the finance team and helps make businesses more profitable. By investing in Ramp, Stripe gets a step closer to its goal -- making internet businesses bigger and more profitable -- without Stripe having to actually build customer-facing software in-house.

Why did Stripe pay a 50% markup?

Stripe brings a lot to the table for Ramp. Why did it pay half a billion dollars more than other investors?

If you’ve watched Shark Tank, you’ll often hear the Sharks beat founders up on valuation by saying something like, “I’m going to make your company 100x more valuable. Wouldn’t you rather own 10% of $1 billion than 100% of nothing?” Sharks know their value, they’re on their home turf, and they have the leverage, so they squeeze founders to get the best deals for themselves.

That works for first-time founders from the middle of nowhere selling magnetic glasses holders. It doesn’t work on Ramp in the middle of unprecedented growth and a hypercompetitive round.

So in this case, with two parties playing the long game, I think the opposite happened. Stripe probably said, “Look, we can make you at least 50% bigger almost immediately, so that means that we can afford to pay 50% more.” They identified Ramp as the best product in a space in which they want to play, saw its product as complementary, and sharpened their pencils to make a deal happen. Backed by, and partnered with Stripe, Ramp should be able to grow faster than it could on its own.

It’s like an inverse Schrödinger's investment: is a 50% markup really a 50% premium if the investment makes the company 50% more valuable?

What’s Up Next for Ramp?

After a crazy month, Ramp has $115 million more in the bank, committed investors, and the best partners a fintech company could ask for. When you have all that, what do you do with it?

First things first: if you have a lot of money in the bank and Founders Fund on the cap table, you need to open a Miami office.

Kidding. That would make it far too easy for Logan to find them.

The answer, of course, is that Ramp will use the money and support to increase its velocity and steepen its trajectory by hiring more top people. Remember, it left some valuation on the table to make Ramp’s equity attractive to new hires. And they’ll have no shortage of things to build.

Now that Ramp has Trojan Horsed its way into the CFO’s office, where all of the money sits, there are all sorts of things it might do. Businesses spend about $1.5 trillion on corporate and small business cards every year, but B2B spend overall is a $130 trillion market.

It could automate savings, like a B2B Paribus or DoNotPay, by recognizing when companies are overspending on products and reaching out to vendors to negotiate on their behalf.

It could build the bill.com killer for its customers, bringing AP and credit cards into the same place.

It could build APIs to connect all of a company’s financial software and automate workflows.

It could team up with fellow Stripe/Thrive portfolio company, Check, to offer payroll through Ramp.

The Stripe investment hints at something bigger, though. Remember that Stripe is the Platform of Platforms. Ben Thompson Drew it up, and I added a Ramp logo…

Could Ramp become Shopify for the CFO and Finance Suite? Already, Ramp customers will be able to issue virtual and physical credit cards through Stripe Issuing. It’s not hard to imagine that Ramp could:

Offer bank accounts (like Shopify does with Balance) through Stripe Treasury.

Offer financing to customers through Stripe Capital.

Handle more B2B payments through Stripe Invoicing and ACH, giving it the ability to play in the full $130 trillion market more quickly.

As Stripe builds new products and improves existing ones, Ramp’s customers benefit. For the price of an interchange fee that they’d have to pay to use any corporate card, they get two of the world’s best and fastest product teams building software to help them make their businesses more profitable.

Ramp is playing the long game. If its customers wins, it wins. With Stripe on its side, a fresh $115 million in the bank, velocity and trajectory at its back, and all of business spending to go after, I think these rounds are going to look very cheap, very soon.

Thanks to Eric and Karim for letting me behind the curtain, and to Dan for editing.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Monday,

Packy

Witnessing Eric and Karim execute on their vision has been incredible. Ramp and Tesla give me hope for a future where the largest companies in the world practice conscious capitalism.

This is the best fundraise announcement I've ever read. Thanks Eric & Karim for doing letting us behind the curtain & packy for being packy :)