Playing Solo Games

Not Boring Capital: Fund I, Update II

Welcome to the 193 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since Thursday! Join 80,476 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… MarketerHire

Work is becoming more liquid. You no longer need to limit your company to whoever happens to be available and willing to work full-time at the time you’re hiring, nor do you need to spend months and your team’s valuable time finding that “good-enough” marketer. With MarketerHire, you can bring in world-class marketers a la carte.

MarketerHire matches your business with expert marketers perfectly suited for the task at hand -- the kind of marketers that you might not be able to find, hire, or afford on your own. Even better? They do the heavy lifting, and deliver you one hand-picked marketer tailored to your requirements. And it works. MarketerHire’s expert marketers have tripled their customers’ revenue in a matter of months.

In fact, your feedback on MarketerHire has been so strong that I invested in the company.

Just set up a call with MarketerHire, tell them what you’re looking to accomplish, and they’ll match you with the one right marketer for you.

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday! Three months ago, I announced that I was raising an $8 million venture fund, Not Boring Capital. In the announcement, I shared both the memo that I used to raise the fund and the quarterly update that I’d just sent to LPs.

One more quarter down, $9.9M raised, and Fund I mostly deployed, I want to share an inside look at running a small fund during one of the wildest markets in history.

Just like companies need to send updates to their investors, investors need to send updates to their investors. Part of what I want to do with Not Boring is to make all of this more accessible and less closed off, so I’m opening up the LP Update I sent this weekend, with stats on the last quarter and an outline of my strategy as a Solo GP of a small fund, with everything but company updates and any confidential company details.

Everyone is becoming an investor, and if you’re reading Not Boring, chances are you’re investing in something. Hopefully there are some takeaways in here that are useful as many of you go on (or continue) that journey. If you’re not investing, and are actually doing real things like building companies, I hope it’s useful as a way to think through your own strategy given your own unique circumstances.

Let’s get to it.

Playing Solo Games

Two of my favorite essays this year were Everett Randle’s Playing Different Games and Dror Poleg’s Andreessen Pulls a Bezos. The essays break down the strategies employed by two of the world’s largest and best venture capital investors, Tiger Global and a16z, respectively.

Before this year, I’d never given much thought to venture capital firms as businesses. Most people probably hadn’t, except for the people managing the funds (and often, probably not them, either). When capital was harder to come by and funding rounds were less competitive, funds focused more on their investment strategy -- we invest in seed stage fintech deals, we’re a multi-stage fund focused on emerging markets, we’re early stage investors -- than their competitive strategy -- an action plan to gain competitive advantage over rivals as evidenced by superior performance, often measured in Return on Investment (ROI), or in venture capital’s case, Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC) or Internal Rate of Return (IRR).

They hadn’t spent time digging moats, which Flo Crivello defines as “those barriers that protect your business’ margins from the erosive forces of competition.” As Redpoint’s Logan Bartlett satirized:

Dror put the same idea in non-tweet format:

Venture capital investors are big fans of the word "strategy," but they hardly give it much thought in their own business... As Michael Porter points out in the book about strategy, acting strategically means "doing different things" rather than "doing the same things better."

VCs can’t just try to be “better,” they need to be different. The rules of the game have changed. In The Cooperation Economy, taking inspiration from both Randle and Ben Thompson, I drew up The VC Smiling Curve:

As a Solo GP (short for General Partner), I’m clearly biased in thinking that differentiated funds -- quite literally, funds who do different things, like Tiger or a16z -- and Solo GPs are going to do great while commodity funds get crushed. That makes sense for the differentiated funds, and their strategies have been well-covered.

It’s less intuitive why Solo GPs, like me, could outperform, given that we have far fewer resources, smaller (or, in my case, no) teams, and often less track record. I’ve seen less written about that topic other than the “Everyone is an investor” and “Someone with a TikTok Account is a VC Now LOL” articles, so I figured I’d share my strategy.

This whole thing is a work-in-progress, and it’s way too early to tell if this strategy will work, but that’s part of the fun. Let’s pull back the curtain and dive in!

Not Boring Capital: Fund I, Update II

Welcome back for Not Boring Capital, Fund I, LP Update II.

I hope you all enjoyed your summer and the start of your fall, and that most of you got the chance to rest and relax. Not Boring Capital did not.

In Q3, we have invested $6.0 million into 59 companies (60 investments including a follow-on), for an average $100k per company. We had our first markups (all of which are yet to be publicly announced) and our first public token sale.

Braintrust launched its token and is currently worth $2.3 billion — our first company to go public and a 14x return in a couple of months. Adam and the team at Braintrust are building something special, and did a fantastic job with the public sale, with $BTRST already trading on Coinbase. Short-term prices post-public token sales are always a little bumpy, but that’s noise. In the long-term, I believe that Braintrust’s community-owned model is going to wipe the floor with companies like UpWork. Braintrust will be a reference point and playbook for how to use tokens to supercharge existing business models.

It feels good to get the first markups and public sales under our belt, but we’re obviously just getting started. In the first update, I mentioned that I was a little self-conscious about the pace of deployment in Q2. We did 20 investments. I thought that was fast. In Q3, we tripled that pace.

That was faster than even I anticipated, but I’m thrilled with where we’ve landed and the portfolio we’ve built. The thesis is working better than I could have anticipated or even hoped. We’ve been seeing a ton of great deals, and have been able to win allocation in them.

This update will have three sections:

Portfolio Stats. High-level overview of the portfolio.

Not Boring Capital’s Strategy. Or, how I’m thinking about operating as a small, non-lead fund.

Investments. A selection of Not Boring Capital’s Q3 investments.

Let’s get to it.

Portfolio Stats

We invested in 79 companies in the first two quarters, with 16 more closed in Q4 or in process. When those deals close, we will have deployed Fund I.

It’s very early -- the average investment is 73 days old -- but already, there are good signs of progress:

First Public Token Sale

First Closed Markup

A big handful of others in closing or with signed term sheets

There are two obvious caveats here -- this market is wild and markups aren’t cash -- but I’m happy with how things are starting to shape up.

Stage Mix

In the Fund I Memo, I wrote that I was aiming to invest ⅓ in Pre-Seed and Seed, ⅓ in Series A, and ⅓ in Series B and beyond. Round names have become a little meaningless, but breaking it down by valuation at the time of investment (and yes, I know, as Lan said after the last update, “I LOLed when seeing your definition of preseed valuation :-)”), here’s what it looks like:

As of the end of Q3, as with Q2, we are leaning a little earlier than anticipated, with 84% of our dollars going towards investments from Pre-Seed - Series A (as defined by the valuation ranges) and 16% going towards Series B deals and beyond. This will shift a little later as some of the pipeline closes. Here’s a look at our investments by stage (stage name, not valuation) today:

Vertical Mix

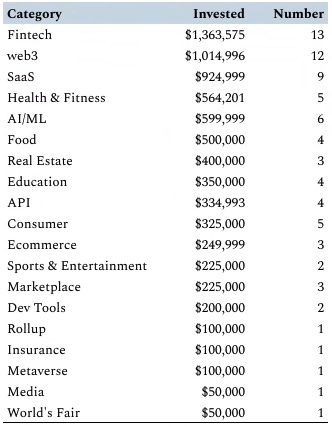

Fintech remains the leading vertical for Not Boring Capital, by both number of investments (13) and dollars invested ($1.36 million) with new additions like Ramp, Unit, Lithic, Modern Treasury, Flexbase, Equi, and Zage joining the fold.

If you’ve been reading the Not Boring newsletter, you won’t be surprised to see that the fastest-growing category is web3. In Q2, we made only one web3 investment, Mirror, and in Q3, we invested just under $1 million in 11 web3 companies and projects, including Rainbow, Eco, XMTP, Braintrust, Massive, Optilistic, Alongside, Meow, Rare Circles, Syndicate, and Anima.

Web3 will continue to be our biggest category for the remainder of Fund I, with 6 of the 16 to-be-closed deals squarely in web3 and three more web3-adjacent, and certainly into Fund II. This shift reflects both my bullishness on the space and the increased dealflow we’ve seen as a result of going deeper down the rabbit hole and writing more about web3.

That said, I’m happily continuing to invest in both web3 companies and in companies that have never even heard the word crypto. I’ve gotten the question many, many times over the past couple months: “Why don’t you just become a registered investment advisor and go all-in on web3 investing?” There will be massive winners that incorporate web3 tools, and massive winners that don’t, and shouldn’t. Companies like ScienceIO, NexHealth, Kingdom Supercultures, Fount, and many more wouldn’t make any sense as web3 companies, at least for a long time, and most of the fintech companies in the portfolio, with whom web3 theoretically competes most directly, work far better without tokenizing, even if they might incorporate certain web3 features and work with web3 clients down the line.

Not Boring Capital’s strategy involves investing in as many of this generation’s great companies as possible, which means leaning in hard to web3 but not being dogmatic and recognizing which business models and technology stacks give which projects the highest likelihood of success.

Speaking of Not Boring Capital’s strategy…

Not Boring Capital’s Strategy

In its first six months, Not Boring Capital invested nearly $8 million in 79 companies from Pre-Seed to Series E across 19 verticals and three continents. We have a pipeline of deals we’ve committed to that are closing imminently that take us to the full $9.9M. That’s not, as I understand it, a typical approach to venture capital, even for a solo GP. I was self-conscious about the pace and breadth in Q2, but as I’ve thought about it more, I believe that this is the best strategy for us.

I spend a lot of my life writing about other companies’ strategies. It’s only fair to turn the lens on myself. This isn’t a “How to do Venture Capital” -- I wouldn’t be the right person to write that -- but a “Here’s how I’m thinking about my own strategy given the specific position I’m in.”

I had a rough outline when I set out to raise the fund in April, but it’s taken me six months of experience to fill in some of the details and figure out how it all fits together. I’m certain that Not Boring Capital will continue to evolve as both I and the market do.

In the memo I wrote to help raise this fund, I wrote that I needed to do three things for us to be successful:

Pick the Right Investments

Get Allocations

Help Portfolio Companies Succeed

And that the Not Boring Flywheel helps with all three:

That still applies, and it’s working better than anticipated, so since then, I’ve refined the approach a little bit, and I’ll analyze it here using the strategy kernel framework from Richard Rumelt’s Good Strategy, Bad Strategy.

According to Rumelt, good strategy has a basic underlying logic, which he calls the kernel. “The kernel of a strategy contains three elements:

A diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge,

A guiding-policy for dealing with the challenge, and

A set of coherent-actions that are designed to carry out the guiding-policy.”

For Not Boring Capital, there’s a three-part diagnosis:

Maximize winners > minimize losers.

The rules of the game are different for a small solo fund like Not Boring Capital.

The newsletter is our unfair advantage; I need to protect time to make it good.

The first part is well-known to everyone reading this: power laws drive venture returns -- i.e. the couple biggest winners deliver most of the returns for a fund. The job is to invest in and support as many of them as possible. It’s not about minimizing losers; it’s about maximizing winners.

(On the most recent Acquired episode, Michael Mauboussin explained a lot of this better than I can, and you should definitely listen. Great episode, Ben and David!)

This piece can’t be overstated. It sets the base rate for the whole strategy. The data backs this idea up, too.

In late 2019, the AngelList Ventures data science team released counterintuitive study results that found that, “At the seed stage, investors would increase their expected return by broadly indexing into every credible deal.” The logic was simple: missing the best seed deals comes with theoretically infinite regret, whereas investing in a loser only costs you your investment.

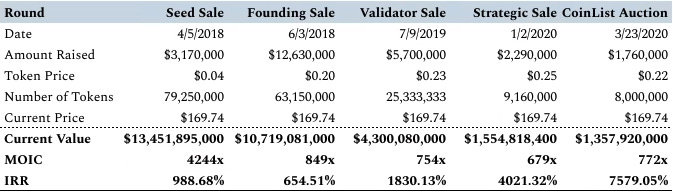

As an extreme example, let’s look at the Solana seed round, which I wrote about in Solana Summer:

At current prices (when I wrote this part a week ago), investing in the 2018 Solana seed sale has returned 4,244x for an IRR of 988.68% (not even including the impact of staking in the intervening 3.5 years). It was not an obvious investment. Many top funds passed, others committed and then pulled out when the market turned.

Let’s say Not Boring Capital had been around back then, and I decided to invest $100k into Solana out of a $10 million fund. That $100k investment would be worth $424.4 million today. Even if every other investment in the fund went to $0, the fund would have returned 42x at a 191.9% IRR pre-fees. That breaks the charts, like this one from AngelList’s VC Fund Performance Calculator, which only goes up to 8x Net TVPI (Total Value to Paid In). In other words, you would have had one of the best performing funds of all time even if you were completely wrong 99% of the time!

Now the Solana example is obviously extreme. That’s one of the best performing investments of all time, and it was very non-obvious. Honestly, it would take some mental gymnastics to convince myself I would have invested. But there will be more Solanas; companies (and protocols) are getting bigger, faster than ever before.

When I sent the Q2 LP Update, I mentioned that there were 750 unicorns on CB Insights’ Real-Time Unicorn Tracker. Today, 90 days later, there are 866. Let’s update our Apple vs. Unicorns chart:

The unicorns have overtaken Apple as, over the past quarter, more than one new unicorn was born every single day.

It’s not just private market mania fueling valuations, either. Crunchbase reported that 83 unicorns went public in the first nine months of 2021 at a combined market cap of $958 billion, for an average public valuation of $11.5 billion at IPO.

That seems … high. More soberly, The Information reported that there have been over 100 tech IPOs worth more than $300 billion combined so far this year, and we have the better part of a quarter left.

Companies are getting bigger, faster, and investors, having seen how big tech companies can get, are giving them more credit for future growth. That means higher valuations at earlier stages, which would mean compressed returns if outcome sizes were static… but they’re not. In Compounding Crazy, I looked back at the Nasdaq’s combined market caps since 1971. They’ve grown at a 10.5% CAGR over that period. If you looked backward at nearly any point, you would have felt like you were at the top, and then the market kept growing. If you project out the next decade at the same 10.5% CAGR, the combined market cap of the Nasdaq 100 Index will grow from $20 trillion today to $54 trillion in 2031.

A lot could go wrong. There will be ups and downs along the way. But the rate of innovation is increasing, companies are getting bigger, faster, and investors are beginning to internalize the impact of compounding better than ever before. Over the life of Not Boring Capital, outcomes are likely to get bigger, not smaller, and there will be more Solana-like opportunities that we don’t want to miss.

The second piece of the diagnosis is that the rules of the game are different for a small solo fund like Not Boring Capital. We are structurally set up to be able to invest in a lot of the most credible companies. We don’t lead deals. We don’t sit on boards. The newsletter generates strong dealflow. If we invest a little bit in companies that can break out, I can often pull the “Deep Dive” arrow out of the quiver to write bigger checks in later rounds. We can often get $250k allocation but rarely $1 million. Time isn’t a constraint, but allocation often is.

At the same time, the biggest funds are getting bigger, which has been well-covered. What’s less appreciated is that, counterintuitively, the bigger and better the big funds get, the better it is for small funds like Not Boring Capital. Bigger funds mean more management fees going towards bigger teams and better tooling to better diligence and support investments. They can meet and spend time on more companies, in a more sophisticated way, particularly in a world in which Zoom means getting days back that would have been spent on travel. Then, they get to put more resources to bear on their portfolio companies’ behalf. As a small, solo fund that’s no threat to lead and is a friend to all, we get to piggyback on all of that work for free, which saves time and lets us meet with, invest in, and write about more companies.

The third part of the diagnosis is that without the newsletter, I would be a very average venture investor at best. I probably wouldn’t be doing this. I would see fewer deals, spend less time thinking deeply enough about companies and markets to put my thoughts out there, and win very few allocations in more competitive deals. No Not Boring, no Not Boring Capital.

All of those inputs combine into a guiding policy for Not Boring Capital: set Not Boring Capital up to see and invest in as many great companies as possible by increasing high-quality dealflow and time spent with companies while protecting time to write.

I want to put particular emphasis on the “great companies” piece here. Seeing and investing in as many great companies as possible does not mean investing in as many companies as possible. It doesn’t mean investing in everything. I say no a lot more than I say yes. If I invested in every company, even every “credible” company, it would mean less when I did invest. But since we invest in companies across stage, vertical, and geography, we can say yes to a lot of companies while keeping the bar high.

The diagnosis and guiding policy are interesting to write about, but the rubber hits the road in the coherent actions, the actual things we do to execute on the strategy. Coherent actions are coherent because they work together to create something that a competitor can’t just copy-paste. Walmart is a canonical example here: to profitably match Walmart’s everyday low prices, you’d need to recreate their whole supply chain, distribution centers, inventory management, retail footprint, and more. If a competitor simply lowered their prices, they’d lose money and go out of business.

A good test of a coherent strategy is whether you could publish it online for all to see and still feel confident that others wouldn’t be able to replicate it. So here we go.

For Not Boring Capital, the coherent actions I use to carry out the guiding policy need to involve trade-offs and take advantage of my comparative advantage. I can’t be the best at everything, so I need to focus on areas where I have the most leverage and de-emphasize areas where I don’t. Specifically, that means more time writing and talking to founders, and less time doing diligence and in-person coffee chats. Here are a few of the actions:

Write about the spaces I want to invest in. Writing about the things that I’m most excited about is like a bat signal to companies in that space. Most of our dealflow comes inbound and is concentrated around spaces and themes I write about, like web3, fintech, and future of work. That means seeing more companies, and it also means I’m prepared when I do.

Share deals with other solo GPs and funds. When I wrote The Cooperation Economy, the thing that sparked the idea was that so many solo GPs have been so generous to me and are generally very collaborative with each other. A lot of the deals you’ll read about below came from intros from other solo GPs (Ankur and Sriram deserve a special callout for sharing the most deals we’ve invested in), many of you, and other investors big and small. It’s a more collaborative space than I was anticipating, and less time fighting means more time to do all of the other things.

Write Sponsored Deep Dives on great later stage companies. Great later stage companies don’t need money — everyone wants to give it to them — but they always need customers and employees. Writing Sponsored Deep Dives helps us get into competitive deals because they help me form stronger relationships with the founders and understand the companies better than most other people. Ramp, Unit, Lithic, Modern Treasury, and Scale are great recent examples here, as is Sky Mavis (although that piece wasn’t sponsored).

Don’t worry about % ownership. I don’t want to miss out on deals just because we don’t hit some ownership target. For leads and other funds who are constrained by time and bandwidth, it might make sense to stick to ownership targets to properly allocate that time and bandwidth, but given our approach, the name of the game is just to invest in great companies at whatever level we’re able to (within reason).

Apply a strong filter upfront. I only take meetings with companies if I think that there’s a very good chance I’d want to invest. That means it’s either in a space I know about and have a thesis on, or if it’s not, that it comes from someone I trust who I’d consider to be an expert in their space. I probably only take meetings with about 20% of the companies sent to me. That might mean missing some winners, but I would drown otherwise.

Spend less time poking holes in companies. This might be a controversial one to say out loud, but I think it’s important to show that there are trade-offs to my approach. I’m a one-person, generalist shop. I am not going to be doing as much diligence as a lead investor, or a sector-focused investor, might. I am happy to trust diligence from top funds and more knowledgeable friends. I understand that this approach may lead to more mistakes (although it may also be helpful to not talk myself out of deals), but in order to both write and invest in more great companies, two areas where we have a competitive advantage, we need to make trade-offs in places where we don’t.

Amplify portfolio companies using my reach. It would be impossible to pursue the high-volume strategy I’m pursuing as a one-person shop without leverage. Our leverage comes from the fact that I’m able to move the needle for companies with the newsletter, Not Boring Founders podcast, Pallet job board, and my twitter. Whether helping explain Equi to a wider audience (see below), interacting with Party Round on Twitter, listing portfolio company jobs on the job board, or turning the mic on for a conversation with a founder, we can have a high helpfulness:time spent ratio. I’m particularly excited about the Not Boring Founders podcast, which I’ve started doing recently. It’s a great way to catch up with our founders and give them exposure at pivotal moments, and it doesn’t take a lot of time.

Work with companies behind the scenes. That said, I don’t just want to be a pretty Twitter profile. I’ve really enjoyed digging in with portfolio companies behind the scenes on how they tell their stories, working with them on decks for their next rounds (which also gives us early visibility), introducing them to investors or potential hires, or digging into a strategic challenge. I was an operator for the past six years, and love getting to dust off those skills, and at the very least, share all of the mistakes I made. Plus, writing about and meeting the amount of companies I get to meet gives me intel on the market that can be useful to other founders and helps make strong introductions. (Never other companies’ private information though -- the one thing that could blow this all up quickly is tarnishing my reputation).

Of course, things could go wrong with my approach. The most obvious risk areas are:

Investing in a lot of companies and still missing the winners

Less time diversification

Inability to raise future funds

Investing in a company that looks like the leader in a competitive set now when the ultimate winner has yet to be built and conflicting myself out

I can’t be helpful enough to this many portfolio companies and lose reputation (this one’s in my control and I’m always developing more channels to help)

There are certainly others. This strategy could be completely wrong; it’s going to take a very long time to learn if it worked. For now, the only thing I have to go on is the companies we’ve invested in, and I couldn’t be more excited about them.

Investments

Now for the fun part: meet the Not Boring companies. As with the last update, I’ll take Gaurav’s advice and break investments down into three buckets -- Core, Explore, and Growth. As a reminder, this is how I’m splitting up the categories:

Core: Each has the potential to return the fund in the bull case. This should be about 75% of the total dollars invested.

Explore: Smaller investment in order to get a seat in the next round or increase deal flow. High upside, but investments too small to reasonably expect they’ll return the fund. This should be 5-10% of invested dollars.

Growth: Later-stage or otherwise safer investments with lower ceiling and higher floor. This should be about 20% of invested dollars, and that 20% should be able to collectively return the fund once.

We’re tracking roughly in line with that split:

We have a few Growth deals in Q4 that will bring that % of dollars invested up.

[Note: I’m removing company writeups to keep company information confidential.]

You can see all of the companies in the Not Boring Capital Fund I portfolio as of the end of Q3 here:

Go learn about these companies, buy their products, and apply for their jobs, and mark up their next round :)

Looking Forward

This is new, not from the LP Update

I feel incredibly lucky to get to run Not Boring Capital. I wasn’t sure how I was going to like being a VC coming into this, but with two quarters under my belt, I can tell this is going to be something that I want to keep doing for a long time (as long as the strategy works, LPs continue to trust me with their money, and founders are willing to take it from me).

As I go, I want to keep getting the Not Boring community more involved in the process. I’d give myself a “C” on that so far: on the positive side, I’m trying to share as much behind-the-scenes as I can to demystify VC, I’m writing about our portfolio companies, and many of you are LPs, but on the negative side, I haven’t been able to make it as inclusive as I want.

My biggest miss so far is that I haven’t been able to get more of you involved in Not Boring Capital. When I opened it up, I expected something like 50 people to apply. I was off. 742 people submitted over $36 million of interest, which completely blew me away… and overwhelmed me. I accepted as many people as I could, focusing on women and people of color, and ended up with 133 Limited Partners (LPs), which is a lot but not as many as I would have liked, before running up against the $10 million limit set by the SEC.

Here’s how it works: if you have over 100 LPs in a fund, all accredited, you can only raise $9.999999 million, and can only go up to 249 LPs max. I think the rule is completely nonsensical -- if you have fewer than 100 LPs, you can raise more than $10 million, and these are all accredited investors, who the SEC deems sophisticated enough to invest. A cap on the number of those investors seems odd and arbitrary (leaving aside how confusing it is that people can trade in options but not invest in startups altogether). But rules are rules (and I’ll keep trying to find ways around them). “Number of Not Boring Reader LPs” will be a key metric for me, and as regulations open up and there’s more clarity on what I can do with DAOs and tokens, I’ll find other ways to share upside with as many of you as possible.

In the interim, I’ll keep sharing what I learn (misses and all). There’s more opportunity for individuals to invest in startups and in funds than there ever has been -- through AngelList, PartyRound, Republic, Syndicate. Web3 means more opportunities to invest in tokens earlier in companies’/DAOs’/protocols’ lives. Hopefully you can apply some of what you read here to your own investing.

That’s actually the biggest tail risk to all of this that I didn’t mention in the original LP Update: that over time, individuals outcompete even solo GPs for allocation in earlier rounds, that even the Solo GP structure is too heavy because of the check sizes I need to write to have a meaningful impact on the fund. I’m in the middle of a deal right now in which about half of the investors are pseudonymous twitter accounts. Syndicate will only make this easier. A good strategy is a flexible guide; as the diagnosis changes, so must the guiding policy and coherent actions. It’s going to be fun to stay on top of it so that I don’t get disrupted. I’m excited to put Clayton Christensen to work alongside Richard Rumelt.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

We’ll be back to our regularly scheduled web3 programming on Monday!

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Wow what a great read. Thanks, Packy.

One question, if you're fully deployed, how are you going to do follow ons? Looks like you invested $7.8m already, and have some more deals to do in Q4. Are you reserving very little for follow ons?

Will SEC rules let you start funds simultaneously? Like Fund 2A, 2B, 2C with 100 LPs each?