Minimally Extractive Meta

Why Zuck Might Have to Actually Contribute to the Open, Interoperable Metaverse

Welcome to the 1,316 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! Join 82,644 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts (shortly)

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by…. Masterworks

Once you realize what’s happened in the past week, the only thing you can say is: HOLY SH*T

Someone made $8 billion buying Shiba Inu coins

Tesla surpassed $1T market cap

Bored of reality, Zuck officially went all in on the Metaverse

Quality chaos does keep things interesting. But when it comes to your financial well being, less is more. Despite popular belief, you don’t always need to take big risks to get big rewards.

Recently I added one of the most consistent and overlooked investments in history to my portfolio. It’s one that billionaires have used to grow but also protect their wealth for generations. This is an asset class that will explode by over $1 trillion dollars in under 5 years. And, it beat the S&P 500 by three fold from 1995-2020 with nearly 0 correlation to public equities.

Most billionaires are bullish on this asset class. In fact, they allocate roughly 10-30% of their overall portfolios to it.

This might shock you, but this asset class I’m talking about is contemporary art. New York City’s newest $1B fintech unicorn, Masterworks.io, has revolutionized the lucrative art market by making multimillion-dollar paintings investable like a company’s stock.

With already over $250M AUM, Masterworks is off to the races. I’ve invested in eight of their offerings and will be allocating more soon.

Use my private link to skip the waitlist today.*

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday!

On Thursday, when Mark Zuckerberg announced that his company was changing its name from Facebook to Meta, I missed it. I was filming a video with a portfolio company, talking about, of course, the Metaverse. Whether it should be open or closed. What its currency might be. How web3 ties into the whole thing.

When I got out of the shoot, I opened up Twitter and saw that it had happened. My whole feed was Meta jokes. I didn’t want to miss out, I quickly fired off a Meta joke myself.

In the intervening four days, many of my favorite tech writers have put out Meta content; Ben Thompson and Matthew Ball both got direct access to Zuck himself. My first instinct was: don’t write something on Meta. It’s been done, everyone did it, they did it well, and Zuck didn’t even slide into my DMs.

But who am I kidding? There’s no way I’m not writing about Meta.

This isn’t a piece about whether it’s a good name, or whether Facebook just wanted to change the narrative to get out of trouble after another recent scandal. Those have been written.

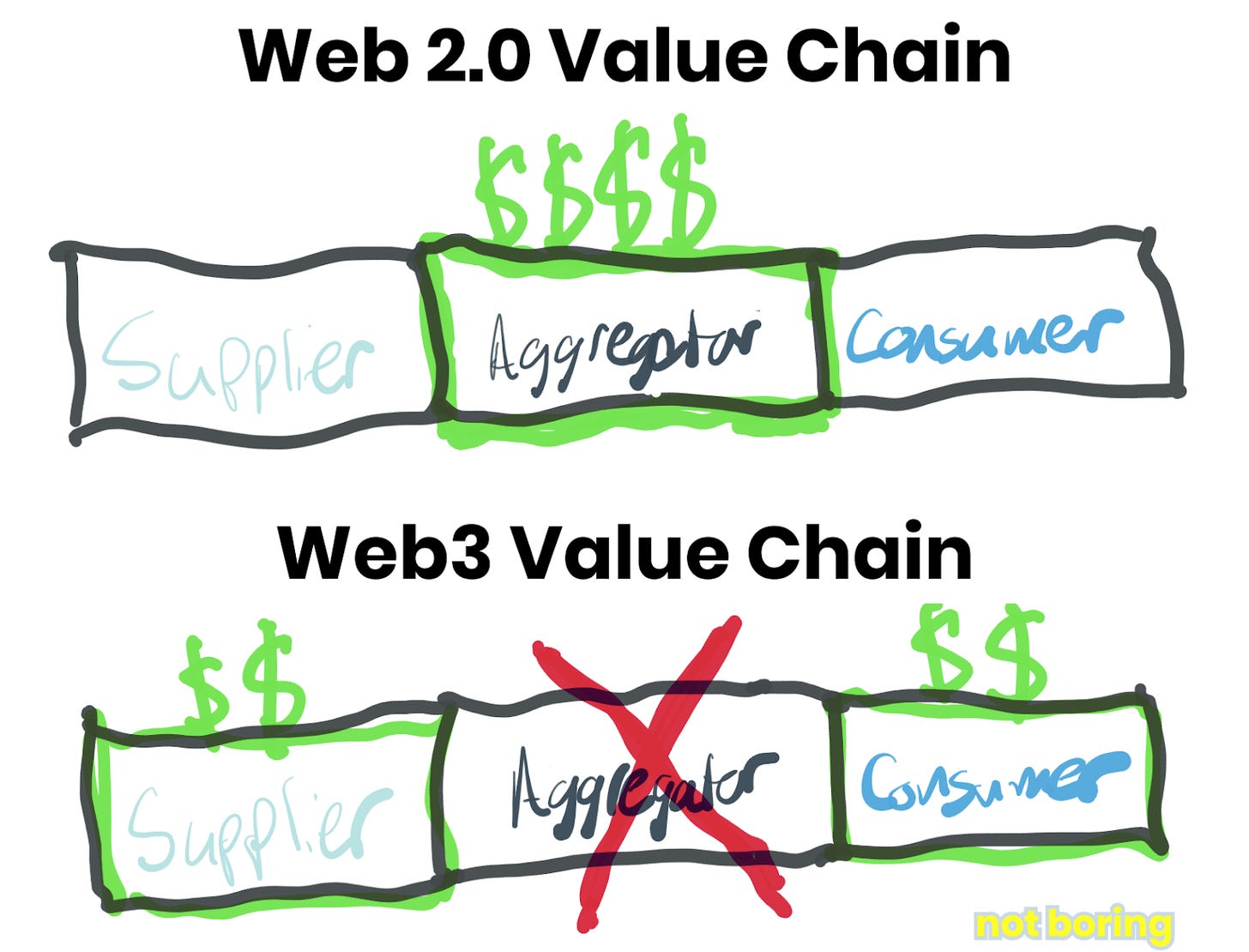

But I’ve written about the Value Chain of the Open Metaverse and have defended Facebook’s business even though Everybody Hates Facebook, and this is a major development on both of those fronts.

Maybe the question isn’t whether the Metaverse will be open or Facebook-run, but whether there’s room for Meta in the Open Metaverse.

Let’s get to it.

Minimally Extractive Meta

It’s unbelievable how much better AI has gotten in the past decade. Look.

Here’s Mark Zuckerberg on-stage with Kara Swisher and Walt Mossberg talking about Facebook’s privacy issues back in 2010:

And look at the most recent demo this past week:

Badum tiss. I’ll be here all week.

Jokes aside, Zuck (with the help of the hardest-working Comms team in the business) has gotten so much better at playing the media game that it feels like he’s learning at the speed of AI. Just going direct to Ben Thompson and Matthew Ball in the first place was a savvy move, and the content of both conversations demonstrated at minimum a stronger understanding of the issues at play and the right things to say. At best, he’d have you believe, we’re seeing a new techno-philanthropic Zuck who’s using his company’s vast resources for the betterment of the virtual world.

The picture of the Metaverse that Zuck painted, in the Connect Keynote and subsequent interviews, seems pretty fun, and the role he wants to carve out for Meta feels more than fair. Watching the keynote, I almost felt like we, the citizens of the internet, were taking advantage of poor Zuck. He’s willing to lose $10+ billion per year, all in the hope that his company might be able to take its small and hard-earned sliver of the Metaverse economy one day? Canonize this patron saint of the immersive internet!

But this is Facebook we’re talking about! Or Meta, whatever. And it’s Zuck. We’ve heard his stilted smooth talk before. Can we trust him now?

That’s actually the least interesting question, and one that’s impossible to answer without seeing into his mind, current and future (although we can guess based on the past). The more interesting thought exercise is to assume the worst -- that Meta has the most selfish intentions -- and to ask “So what?”

I think that Facebook’s hard pivot into Meta is a good thing for us citizens of the internet, not because Meta is good -- this isn’t a value judgment piece -- but because the entire system is moving in a direction such that being a good actor is the value-maximizing strategy for Meta, and we could use its vast centralized resources to solve a lot of hard problems.

It’s hard to imagine Meta as good for us if you just look at Facebook today, statically. Taking Facebook and making it 3D and immersive would blow. Imagine living inside this hellhole (no offense to ClickUp, which seems great, congrats on the C!).

Left to his own devices, that 3D, immersive walled garbage can might be what Zuck would have built. It might be the full-stack data ownership play -- from commerce to eyeballs -- that the perma-dystopians have spent the past few days tweeting about. But things aren’t static, and the world is moving towards decentralized ownership and control. This is why web3 matters.

In a world in which people are more used to ownership of their digital assets and identity, Meta’s best strategy will be to operate more like a Minimally Extractive Coordinator than an extractive platform. To reach its full potential, Meta needs to disrupt Facebook by turning itself into something that behaves more like a protocol than a platform.

With an internally omnipotent founder at the helm willing to lose $10+ billion annually, it might have the organizational will to do it. It’s already built the best and most popular hardware in the market, an impressive new act from a social media company with a bloated and terrible core product.

Meta shouldn’t and won’t be the Metaverse. But it can play an important role in “expanding the GDP of the Metaverse” and participate in the upside it creates. Someone’s gotta build all of this incredibly expensive tech over many, many years, and Meta’s a better people’s champion than Apple. (Seriously.) Fresh competition among the giants is a good thing for creators and consumers.

But I know, you probably don’t believe me yet. You’ve been burnt before. I get it. So put on your Quest II and hop down this rabbit hole with me:

The Value Chain of the Open Metaverse

Minimally Extractive Coordinators

Facebook’s VR / AR Strategy

The AppleVerse

Meta’s Metaverse Strategy

Power to the Person

It starts with understanding the how the Metaverse economy will work.

The Value Chain of the Open Metaverse

Back in January, I wrote my first essay on web3: The Value Chain of the Open Metaverse.

After a few conversations with Crucible founder Ryan Gill, the future clicked into focus. I thought crypto was interesting as an asset class then, but I’d realized that if you zoom forward to a time when more of our time is spent immersed in the internet, web3 would become more than a nice-to-have, it would become a necessity.

To understand why, it’s useful to think about the Metaverse as a virtual version of the real world, a place in which people work, play, shop, and socialize as avatar versions of themselves, or many, depending on the context. Just like we buy outfits for our physical bodies and just like gamers buy skins in Fortnite, everyone will buy outfits for their avatars. Just like people want to buy nice homes and decorate them to reflect their personal taste, we’ll buy and decorate virtual spaces. And on and on.

We will spend real time and real money in virtual worlds. Shaan Puri had a viral thread over the weekend that the Metaverse isn’t a place, but the time at which our digital life is worth more than our physical life to us.

If the Metaverse operated like the internet does today, though, we wouldn’t actually own any of those things. They’d be tied to whichever platform we bought or earned them in. Platform changes its mind, lose the items or see their value deflated. Leave the platform, lose the items.

Web3 gives digital items physical characteristics, and as the virtual and physical worlds blend, that will just get more and more important. Specifically, tokens give people property rights in the virtual world. Just like it would be absolutely insane if Nike took back the shoes we bought as soon as we left the store, OpenSea can’t hold your NFTs hostage. Buy an NFT of a digital shirt on OpenSea and it lives in your wallet, to which only you have the keys. You can bring it with you across the internet, and put it on whenever you feel like it.

Platforms and marketplaces have a place in web3 -- OpenSea is a multi-billion dollar company -- but it charges only 2.5% fees on transactions. More value accrues to the creator and the consumer.

Web 2.0 platforms and marketplaces charge a lot more than 2.5%. Airbnb takes roughly ~15% from both sides combined. eBay, which is apparently like an OpenSea for physical stuff, charges a 10% seller fee on most items. Apple and Google take 30% in their app stores.

While Facebook monetizes through ads, and therefore doesn’t have an explicit take rate, its ads business is essentially a tax on anyone who wants to sell online. Plus, the company is very guilty of flexing its muscle and changing rules at the expense of the developers and journalists who built on top of its platform.

In Why Decentralization Matters, Chris Dixon wrote about why centralized platforms always do this. In the early days, centralized platforms do anything they can to attract users, developers, and businesses in order to build up multi-sided network effects.

Once they’ve built those network effects, though, and they know that users, developers, and businesses are locked in, they switch from “attract” to “extract.” The easiest way to grow revenue is to start charging businesses and developers to reach customers, and to serve customers ads or products based on the data they’ve accumulated.

This isn’t evil. It’s just how the incentives work. Users and creators are free to move, although currently, moving to a new platform does mean leaving behind the data, friends, points, followers, likes, assets, and other digital artifacts they’ve created on the platform.

It would be easy to look at Connect and say that we’re in the “attract” stage of Facebook’s Metaverse development, and that they’ll once again switch to “extract” as soon as humanly possible. Which is probably true, except that it might not be possible.

Companies and protocols exist inside of a broader ecosystem. Web 2.0 platforms could extract because all of the other Web 2.0 platforms were extracting, and because users and builders are loath to give up everything they’ve built there. There was nowhere else to go, and even the alternatives that looked attractive had no built-in guarantees that they wouldn’t make their heel turn one day, too.

Crypto, as they say, fixes this.

In some cases, on a local level, web3 means that strong commitments are written into the code itself. The web3 version of Facebook might not be able to arbitrarily change algorithms on which entire businesses and industries had come to rely. That’s important.

But there’s an equally important force, the one that keeps OpenSea in line: competition combined with portability of assets. If OpenSea were to start charging 5% or 10% or certainly 30% to sit in between sellers and buyers, people would move their business to another platform immediately. For decentralized protocols, which are open source by default, the threat of being forked serves as an incentive to treat both the supply and demand side well, and to keep fees as low as possible.

Protocols aren’t businesses themselves. Protocols are minimally extractive coordinators.

Protocols as Minimally Extractive Coordinators

In 2019, Chris Burniske wrote one of the most useful essays out there for understanding web3: Protocols as Minimally Extractive Coordinators.

In it, he laid out a short but compelling argument that protocols will need to extract as little value as possible or risk being abandoned or forked (essentially copied). You should take a couple of minutes and read it, but this summarizes it well:

Protocols provide structure for businesses, but are not businesses themselves; they are systems of logic that coordinate exchange between suppliers (businesses) and consumers of a service. As coordinators of exchange, protocols should be minimally extractive, whereas businesses are incentivized to be maximally extractive (that’s profit, and a business is valued as a multiple of its profit).

From this angle, protocols can be seen as routers of economic activity. Just as the routers of the internet are as lean and efficient as possible, so too should crypto’s protocols trend. The less extractive a protocol is in coordinating exchange, the more that form of exchange will happen.

Protocols can still charge fees. They shouldn’t lose money. They can become incredibly, incredibly valuable (see: Bitcoin, Ethereum, Uniswap, and on and on). But if they charge fees that are too high, they’ll lose. As Burniske put it, “Any unnecessary extraction from the process of exchange is a tax that will ultimately be weeded out by copy-paste competition in the world of open-source protocols.” This applies to fees directly, and also to the protocol’s decision and actions.

When Tron’s Justin Sun bought Steemit, the people who ran the Steem blockchain executed a soft fork of the blockchain to keep him from being able to control it. When some Uniswap users were unhappy that Uniswap hadn’t issued a token, they forked it and created SushiSwap. After both forks, users were free to vote with their feet and dollars between alternatives.

This is the same way that Epic CEO Tim Sweeney, the closest thing we have to a Godfather of the Metaverse, believes that the platforms underpinning the Metaverse should operate. In a July 2020 interview with Deconstructor of Fun, he made the case for open app stores that are subject to the forces of competition instead of the closed and “fake open” app stores that Apple and Google, respectively, run today. Sweeney thinks that platforms in the Metaverse should essentially charge enough to cover their costs plus a reasonable margin, but that they should be subject to market forces:

I think the key is that the economics be completely transparent... I think transparency and open competition there are the critical elements of it.

Sweeney is a missionary for the Metaverse, but he’s also a capitalist, and one fiduciarily obligated to increase Epic’s long-term shareholder value. He wants Epic to make a lot of money, he just understands that in a transparent and open system, the platforms and protocols on top of which the most activity occurs will be the ones that are minimally extractive.

Interestingly, that’s the language that Facebook is using to describe its own plans. Zuck laid out his philosophy for the business model in the Connect video (right around minute 35):

We plan to either subsidize our devices or sell them at cost to make them available to more people. We’ll continue supporting side-loading and linking to PCs so consumers and developers have choice, rather than forcing them to use the Quest Store to find apps or reach customers. And we’ll aim to offer developer and creator services with low fees in as many cases as possible so we can maximize the overall creator economy, while recognizing that to keep investing in this future, we’ll need to keep some fees higher for some period to make sure that we don’t lose too much money on this project.

In his interview with Thompson, Zuck explained the logic:

Our next goal from a business perspective is increasing the GDP of the metaverse as much as possible, because that way you can have, and hopefully by the end of the decade, hundreds of billions of dollars of digital commerce and digital goods and digital clothing and experiences and all of that. And I think the best way to increase the GDP of the metaverse is to have the fees be as low as possible and as favorable as possible to creators.

Zuck sounds like the fourth Collison brother without the charming Irish accent.

Stripe’s mission is “To increase the GDP of the internet,” and this isn’t the first time Zuck’s copied good ideas from other companies, but the same logic that applies to Stripe (and web3 protocols) applies to Meta. If you’re providing crucial infrastructure in a booming space, the move is to get into the right spot in the value chain, lower costs, and do everything in your power to increase the amount of economic activity happening on top of you.

The question is, once you get into that position, do you switch from attract to extract or do you keep fees low?

Zuck, too, is a capitalist, and if he is a missionary, he’s certainly taken a Crusades-like approach to the task. Methods aside, he’s a world-class strategist, technologist, and tactician. If he’s truly planning to make Meta more open than Facebook, it’s because he sees that as the best way to generate the most value for Meta in the market environment he’ll enter when Meta really starts hitting its stride in three to five years.

In such an environment, Meta would be incentivized to be minimally extractive. That would represent a shift in its approach to the Metaverse since at least 2015, pushed no doubt by web3’s growing popularity and influence.

Facebook’s OG VR / AR Strategy

It’s clear that Meta has changed, if nothing else, the way that it talks about its Metaverse ambitions, in response to web3 and individuals’ increased leverage. For starters, it calls it the Metaverse now. It used to just call it VR / AR.

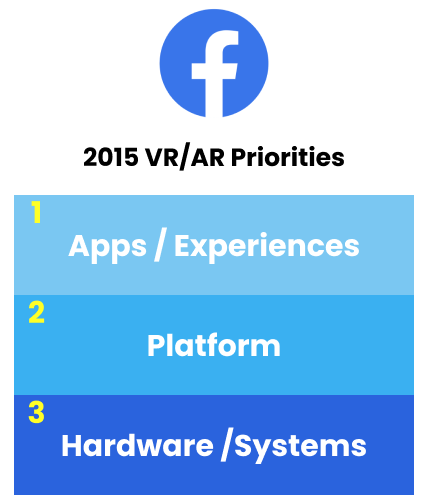

In 2015, when the company formerly known as Facebook was considering acquiring game development platform Unity, Zuck wrote a letter to the internal team working on the deal that has since leaked. In it, he laid out his vision for VR / AR and Facebook’s role in the space (another must-read if you’re interested in tech strategy):

Our vision is that VR/AR will be the next major computing platform after mobile in about 10 years. It can be even more ubiquitous than mobile -- especially once we reach AR -- since you can always have it on.

He also laid out strategic, brand, and financial goals for the company’s investment in the space, spending the most time on financial goals, which includes a discussion of “which aspects of the VR / AR ecosystem we want to open up and which aspects we expect to profit from.”

I think you can divide the ecosystem into three major parts: apps / experiences, platform services, and hardware / systems. In my vision of ubiquitous VR / AR, these are listed in order of importance.

There was nothing minimally extractive about the strategy.

In Apps and Experiences, Facebook wanted to build social communication and media consumption apps, particularly immersive video. This is the most similar to Facebook’s current Family of Apps strategy today, and while Zuck didn’t say it explicitly, I’d expect them to monetize these apps via ads like they do today and build a very large business.

In Platform, Facebook planned to own the “key services that many apps use: identity, content and avatar marketplace, app distribution store, ads, payments, and other social functionality” because “these services share the common properties of network effects, scarcity and therefore monetization potential.” More developers → better products → more money.

Importantly, Zuck wrote that instead of building a full operating system (OS), Facebook’s platform services should be cross-platform, since the advantage for modern OSes comes less from the OS itself and more from “advantaging the OS provider’s own platform services on the devices where its OS is installed.” If Facebook could own the core platform services across all devices, it would get the advantages of being an OS provider without the limitations, and the right to extract value from all participants.

In Hardware / Systems, like “headsets, controllers, vision tracking, low-level linux and graphics APIs,” Zuck admitted that it would be the most difficult part of the ecosystem in which to build a large business. But hardware and systems were still important to Facebook because it would help them accelerate and influence the development of VR/AR, integrate its platform services across all systems, and “if we do consistently great work, it could potentially become an important revenue driver like it has for Apple.”

Overall, Facebook’s vision for the space was that they would:

Be completely ubiquitous in killer apps

Have very strong coverage in platform services (like Google has with Android)

Be strong enough in hardware and systems to at a minimum support our platform services goals, and at best be a business itself.

Facebook essentially wanted to own social, content, and communications apps, like it already did, get stronger on platform in order to reduce dependence on Apple and Google and extract more money from the ecosystem, and build or acquire whatever hardware and systems it had to to support the other two and accelerate the arrival of the next computing platform.

Because there’s just one more thing… the strategic goal:

The strategic goal is clearest. We are vulnerable on mobile to Google and Apple because they make major mobile platforms. We would like a stronger strategic position in the next wave of computing. We can achieve this only by building both a major platform as well as key apps… We are better off the sooner the next platform becomes ubiquitous and the shorter time we exist in a primarily mobile world dominated by Google and Apple.

That goal hasn’t changed. If anything, it’s become more pronounced. Throughout the Connect video, Zuck made thinly-veiled references to Apple and Google and the challenges for creators, developers, and Facebook itself that have arisen from their control of the mobile ecosystem. Apple seems to be particularly top-of-mind. Near the end of the video, Zuck led into the announcement of the company’s name change with a poke at Apple: he used Steve Jobs’ patented “One More Thing.”

For Facebook, Apple is the enemy. And as crazy as it sounds to say: they’re right. Facebook’s biggest contribution to the Metaverse might be making sure that Apple doesn’t control it, or at least introducing enough healthy competition that Apple can’t get up to its old tricks.

The AppleVerse

Despite Facebook’s early lead, many smart people believe that Apple will ultimately build the dominant hardware and operating system for AR and VR, just like they did with the iPhone. That would be a bad outcome.

Given the press surrounding both companies, particularly after the recent Facebook leaks, it’s weird to suggest that the Metaverse would be better off if Facebook had more influence than Apple. According to the 2021 Verge Tech Survey, people have a higher opinion of Apple than Facebook…

… and more than 3x as many people think that Facebook has a negative impact on society than that Apple does:

Apple is the most valuable company in the world. It’s beloved by consumers. I’m writing this takedown on my new MacBook Pro, while wearing an Apple watch, with my iPhone and iPad next to me. When Apple launches its AR/VR/MR glasses, I will in all likelihood buy them. I appreciate the hypocrisy in all of this. But there is also a very strong case to be made that Apple’s involvement in the Metaverse would be far more destructive than Meta’s.

Last week Alex Danco tweeted a series of questions that were ostensibly about Amazon’s Audible…

… but were really about Apple’s take rate.

The reason that you can’t buy Audible audio books, Amazon books, Netflix subscriptions, and all sorts of other things that you should be able to buy on your phone, on your phone is that Apple charges developers 30% to sell their apps in the App Store and charges 30% for all in-app purchases. Whether or not you think it’s technically monopolistic -- Android exists, you might argue, if you don’t like Apple, go there! -- it is fucking absurd and it undoubtedly hurts margins for creators and developers and creates sub-par consumer experiences (see: Audible).

The pain is most apparent in gaming. According to The Wall Street Journal, Apple earned $8.5 billion in profits from its 30% take on mobile games in its app store, “$2 billion more than the operating profit generated in the sector during the equivalent 12-month period from gaming giants Sony, Activision, Nintendo and Microsoft.”

Higher app store fees mean lower profits for game developers and in-game creators. Roblox is a stark example. According to the company, 27% of every dollar spent via Robux goes to developers, 25% to app stores, 12% to invest in and support the platform, and 27% to Roblox itself.

Apple and Google take as much of each dollar spent on Roblox as the company itself and the independent creators and developers who build games and in-game items. That feels off.

Epic recently sued Apple over its App Store practices, and while Apple mainly won, the judge did rule that Apple would need to at least let developers advertise other payment options within the app. This would mean, for example, that Audible could at least explain in the app why you need to use credits and where to buy them. It’s a tiny crack in Apple’s armor.

Matthew Ball wrote an excellent breakdown of the situation in Apple, Its Control Over the iPhone, and The Internet. He convincingly argued that regulators should require Apple to loosen its grip on the app ecosystem, concluding that:

It may feel unfair to force Apple to loosen the controls that led it to such unprecedented success and adoption. Yet problems arising from Apple’s controls are becoming larger every day, as is the company’s unprecedented strength. The future of the global economy is digital and virtual. Broad prosperity depends on platforms that compete to create value for developers and users, and that give birth to new platforms that do the same. Apple is not meeting the moment.

Now, Apple has its sights set on the next computing platform, too. In February, The Information reported that Apple was far along in the development of a mixed reality headset that would “combine virtual reality experiences with games and other applications that use real-life objects surrounding the person wearing the headset.” Based on prototype images The Information saw, they drew this sketch of what the device might look like.

The Information reported that the device could launch as early as 2022. (MacRumors has an updated roundup of all of the news and rumors surrounding Apple Glasses here.) And who am I kidding? I’m almost definitely going to buy a pair when they come out.

But Apple cannot be allowed to run away with the Metaverse. In the Deconstructor of Fun interview, Tim Sweeney laid out what’s at stake:

This Metaverse is going to be far more pervasive and powerful than anything else. If one central company gains control of this, they will become more powerful than any government and be a god on Earth.

If Sweeney is correct, along with the growing number of people who believe that the Metaverse economy will one day be larger than the meatspace economy is today, letting Apple control the Metaverse App Store would essentially give it the ability to tax a large portion of the world’s wealthiest users 30%.

While Apple has been characteristically tight-lipped about any potential Glasses, nothing it’s done to date would suggest that it has any plans to build an open ecosystem. That’s not what Apple does. Closed means incredible products, but it also means that Apple has incredible leverage over everyone in the ecosystem, from the smallest developer all the way up to Meta itself, and the demonstrated willingness to be maximally extractive.

That’s not how the Metaverse should be built. Apple will face pressure from all sides, particularly from Epic whose Unreal Engine will power many of our virtual worlds and Epic’s largest shareholder, Tencent, which has its own Metaverse ambitions. If nothing else, Facebook’s all-in effort to ensure that Apple doesn’t control the next computing platform will be a check on its power and on its ability to tax.

To be fair, if Facebook had been able to control the mobile OS, there’s a good chance it would have done what Apple and Google did. Facebook has never been shy about doing whatever it takes to make profits. It didn’t, though, and as a result, it’s built up a different set of muscles that may fit the current paradigm better than either of those companies. It’s also competing with Apple using a healthy dose of counter-positioning. It’s taking a “moral” stand for selfish reasons.

At the very least, Meta has openly laid out its plan for the Metaverse and paid lip service to interoperability, user ownership, and low fees. Apple has not. Even if Meta doesn’t live up to its words, a world in which it builds hardware and experiences that compete with Apple’s would be better for developers, creators, and users.

But it seems that Meta does understand that one company shouldn’t, can’t, and won’t control the Metaverse, and that the best strategy is to use its resources to make sure that it gets here soon and pulls us away from our phones, grows the GDP of the Metaverse by being minimally extractive, and take a small piece of as much of that growing pie as it can.

What Meta is Building

A lot has changed since Zuck wrote that strategy memo in 2015, both inside of Facebook and around it.

Most importantly, web3 has evolved dramatically and proven its staying power. NFTs in particular have added an entire new part to Zuck’s original ecosystem stack: assets.

The existence of assets that are independent of any one app or platform, that sit above them all in a Superverse, changes the game. Users will be able to log into virtual worlds with their wallets, bring the things they own with them from world to world, directly connect with and message any other wallet and build up their social graph independent of any one app, build an on-chain resume, and own their data. Developers and creators can transact directly with their fans and retain ownership and control over their own work. They can make royalties when their work is resold. That changes everything.

In 2015, when crypto was just Bitcoin and a little Ethereum, Zuck was right to suggest that the Apps and Experiences layer would be the most valuable. Six years later, the Assets layer will be the most valuable, and it will be owned by the users, developers, and creators themselves.

In Who Disrupts the Disrupters, I wrote that web3 would reduce the dependence on Aggregators, like Facebook, and alter where and how developers build.

If the code can make strong commitments, you don’t need central platforms to make and enforce the rules. They just create economic drag. Instead, you can allow creators and consumers to share more of the profits that Aggregators and Platforms previously captured.

Blockchains can make commitments to developers, too. Unlike Apple’s App Store, or Facebook, or Twitter, the rules are known from the start and they don’t change when a company decides it needs to increase profits. If you’re building a new app on top of the Ethereum or Solana blockchains, you know what you’re getting. You can plug into a growing number of superpowers with confidence that they’ll always be there, even if the people behind them go away.

Web3’s skeptics ask its believers to show them the real-world use cases. They’re getting it backwards. Shifting the power dynamics online is web3’s killer use case. Centralized platforms and Aggregators will have less power in web3 than in Web 2.0.

Zuck, to his credit, noticed the shift and seems to be leaning into it. Throughout the Connect video, he called for interoperability over and over again.

When Ben Thompson pushed him on what he meant by interoperability, Zuck responded:

I think we’re each building different infrastructure and components that go towards hopefully helping to build this out overall and I think that those pieces will need to work together in some ways.

We’re trying to help build a bunch of the fundamental technology and platforms that will go towards enabling this. There’s a bunch on the hardware side — there’s the VR goggles, there’s the AR glasses, the input EMG [electromyography] systems, things like that. Then there’s platforms around commerce and creators and of course, social platforms, but there will be different other companies that are building each of those things as well that will compete but also hopefully have some set of open standards where things can be interoperable.

I think the most important piece here is that the virtual goods and digital economy that’s going to get built out, that that can be interoperable. It’s not just about you build an app or an experience that can work across our headset or someone else’s, I think it’s really important that basically if you have your avatar and your digital clothes and your digital tools and the experiences around that — I think being able to take that to other experiences that other people build, whether it’s on a platform that we’re building or not, is going to be really foundational and will unlock a lot of value if that’s a thing that we can do.

The answer demonstrates an understanding that the Asset layer is now the most important, that companies will need to compete on experience to attract creators’ and developers’ efforts and users’ attention, and that interoperability will create a much bigger pie than walled gardens.

I think the logic goes something like this:

Interoperability and ownership increase the value of digital assets. An NFT of a pair of sneakers should be more valuable than a pair of sneakers you buy in Fortnite, because you can use the NFT sneakers in many more places and because they have resale value.

The more valuable the digital economy becomes, the more valuable advertising within digital worlds becomes. Businesses can afford to pay more to acquire a customer if they know they’re going to spend more. And Meta primarily makes money through ads.

Meta wants as many creators and developers building Metaverse products as possible, because more products mean more advertising opportunities and potentially small marketplace fees, so it can keep fees very low to encourage creation.

Unlike Facebook’s products today, it’s anticipating that Meta’s users, developers, and creators will be able to pick up and leave -- or “rage quit” -- more easily, and take all of their assets with them, if Meta shifts from attract to extract.

So it needs to create a model in which it takes a smaller piece of a larger pie in order to do what it does best: aggregate and monetize attention and commerce.

Importantly, Apple likely cannot create a similar model. Apple isn’t a big interoperability fan.

Apple is enemy number one. Zuck realizes that Meta won’t have as much power in the Metaverse relative to suppliers and users as it has in social media. Instead, it wants to make sure that it has more power relative to Apple and Google than it’s had in Web 2.0. Being the first Web 2.0 giant to lean into openness and interoperability in the Metaverse lets it set the rules and influence the playing field on which it will compete against its biggest foes.

Zuck is willing to spend a lot of money to make sure that he can set those rules, and Meta is building an impressive suite of hardware products to accelerate the Metaverse’s arrival.

Amazingly, after flopping on a phone, Facebook has become a very good hardware company.

As I type, my sister is talking to my son on the Portal. She’s in Ghana, he’s in Brooklyn and they’re talking like they’re together (well, she’s talking, he said “car” once). The camera tracks him as he calls around the room. She can even read him stories with interactive on-screen graphics. It’s really good.

I have an Oculus Quest II sitting behind me in my office. While the app ecosystem still needs to be built out, the experience is impressive. It really does feel immersive and magical from the moment you drop into your Home space.

Oculus initially required users to login with their Facebook accounts, but after user outrage, the company relented and lets people login without Facebook’s identity layer, breaking one of the core components of the platform services suite that Zuck identified as crucial in the 2015 memo.

Meta’s recently released AR Ray Bans have limited functionality for now, although early reviews are good, but the video showed a future in which AR would let friends play chess, ping pong, and even attend concerts together just by throwing on a thin pair of glasses.

Ctrl-Labs, which Facebook acquired in 2019, is like sci-fi come to life. Using electromyography, which reads the electrical activity of muscle tissue, it allows users to manipulate digital environments with as little as a twitch. In the Connect video, Meta showed a researcher writing a text by scribbling his finger on his leg and sending with a slight click of the fingers.

On the Apps / Experiences side of the house, Meta seems to be trying to build the places in which we hang out, gather, and work. It announced Horizon Home, a soon-to-be customizable and social starting point for the VR Metaverse journey:

And showed off Horizon Workrooms, the VR office product it released earlier this year.

While there are and will continue to be many, many products competing to be our virtual home and workspace, the Horizon products at least seem to be much better than the core Facebook product, a signal that Meta realizes it needs to compete for its users’ time instead of taking it for granted.

Interoperability means that those competing spaces will be available on Meta’s hardware devices, either through the Quest Store, side-loading, or direct download from websites, and that assets that users accumulate in one space can move freely from one to the other. Being first means that Meta will have an important seat at the table in the discussion around the standards that make the Metaverse interoperable. While that could be a chilling thought, my guess is that they’ll want those standards to be written in a way so as to disadvantage Apple and force it deeper into its own walled garden. Zuck mentioned Epic during Connect and in subsequent interviews; the two companies seem like they’ll ally themselves against a common enemy in shaping the rules for the Metaverse.

Meta will need to compete for developer, creator, and user time, attention, and business in the Metaverse. It knows that. That should force it to build better products, keep fees low, and keep the promises it made at Connect in order to attract its fair share of Metaverse activity.

Power to the Person

In Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, a salesman named Gregor Samsa wakes one day transformed into a giant insect. Will Facebook’s Meta-morphosis turn a giant insect into a more human company?

I don’t think it will have a choice, and everything it said at Connect point to the fact that the company realizes that (or at least realizes that interoperability and openness is the right PR stance).

The involvement of the big companies in the Metaverse is inevitable. In The Metaverse, Matthew Ball wrote, “it’s hard to imagine any of the major technology companies being ‘pushed out’ by the Metaverse and/or lacking a major role.”

As a coordinator of economic activity competing with a default-closed enemy, and as unlikely as it sounds, Meta is the most likely of the tech giants to help build the Metaverse in a way that’s good for creators, developers, and users. Portable assets and interoperability, plus increased media and regulatory scrutiny, should mean that it is limited in its ability to do what it did with Facebook and change the rules on its suppliers to extract more value for itself.

Getting all worked up about Meta controlling the Metaverse is a stale, beta stance to take. It forgets that people have agency and choice.

Over the weekend, Ball tweeted something germane to this whole conversation:

Zuck himself made the same point, in his conversation with Ball and here, in his interview with Ben Thompson:

I think that there’s a real intellectual battle, if you will, about what will be the default package of things that is in our VR experience or our AR experience. We’re trying to propose our set of ideas for how we think that’ll go. Of course, if that ends up not being useful to people, then it’ll go in a different direction, but I think that there’s a good chance that it will be, and I think that that will basically just influence, hopefully, the direction that this whole next platform evolves in, not just for the devices that we’re building, but for the ones that other companies build as well.

There’s a whiff of “that’s exactly what a monopolist would say” in that framing, but there’s also a lot of truth. I’ve made this point repeatedly when people have asked whether the entire concept of a Metaverse is a bit of a dystopian nightmare: we’re not going to be forcibly compelled to enter the Metaverse. People have agency, now more than ever. We’ll use VR, AR, and web3 when they provide a better experience on the dimensions that matter to us; we won’t when they don’t. If Meta extracts more value than it creates, people will leave. And we’ll take our stuff with us.

Obviously, concerns remain. Meta might be able to collect even more data on us if we spend time in its corner of the Metaverse, and it hasn’t proven to be the best steward of that data. And Zuck might be a sociopath with designs on world domination. But he’s a smart, profit-driven one, and I think he really does realize that any closed platform that doesn’t let creators, developers, and users own the fruits of their labor is …

Zuck would probably prefer a Metaverse like the one he envisioned in 2015, one over which Meta has more control and from which it’s able to extract more value. But you have to play the game on the field. There won’t be a closed Metaverse controlled by one company as Ernest Cline imagined in Ready Player One, but an Open Metaverse built by stitching together millions of virtual worlds, apps, experiences, and assets, accessed via VR headsets, AR glasses, mobile phones, laptops, headphones or whatever happens to be most convenient for each user at any given moment.

Cyber, a Not Boring portfolio company, envisions a Multiverse, one in which users can easily jump from world to world, carrying their assets with them wherever they go. Each door in this screenshot I took of something they’re cooking up now represents a rabbit hole into a new world.

You might access Cyber on a Quest II or Cambria headset and jump into your Horizons Home from the Cyber terminal, or you might jump in from your laptop and enter any number of virtual worlds, galleries, games, events, and experiences. Meta will have to compete to build the hardware and systems through which some people experience the Metaverse, and the worlds, apps, marketplaces, and experiences where they spend their time.

It will have to do so by being minimally extractive. It will need to let people show up with their avatars and assets from other virtual worlds, and to let them take them with them when they choose to leave. At best, it can build a set of protocols, literal and metaphorical, that coordinate economic activity and take its fair cut when it adds value.

In his conversation with Ball, Zuck compared Meta to Bell Labs and Xerox PARC, two institutions that developed technology in the pursuit of a particular goal that ended up creating much more value for other players in the ecosystem than they captured for themselves. Bell Labs created the transistor in its efforts to make long-distance calling better. They made money, but the larger computer industry made a lot more of it. Xerox PARC developed, among other things, the Graphical User Interface that Steve Jobs applied to the Macintosh. PARC developed a lot of technology that helped Xerox sell more printers, but Apple made a lot more money than Xerox. The positive externalities that spawned from those institutions’ research created far more value for the world than any one company could ever capture.

The hope for Meta’s involvement in the Metaverse is that something similar happens this time around. Meta is one of the very few organizations in the world that has the resources and capabilities to build foundational technology to accelerate the arrival of the Metaverse. Simultaneously, web3 is helping to coordinate the resources and efforts of millions of people who want to build a more open virtual world. Already, that’s influenced the way that Meta talks about its ambitions. If you believe what Zuck has said over the past few days, it’s influenced how and what Meta is going to build.

Questions still abound. We’re talkin’ about Zuck. Meta might put itself in a position to be the world’s most popular wallet. We haven’t even talked about Libra/Diem and all of the challenges it’s had with its first foray into crypto. Facebook will know more about our eyeballs than Worldcoin, and will know even more about us, down to the twitch of our muscles. The list of concerns is long and growing and hundreds of journalists and thousands of tweeters have covered them well.

The most important question might be whether Meta will build in such a way that people can own and monetize their own data, not just their assets. I would love to see a world in which Meta is forced to build a protocol in which users are directly compensated for their attention and Meta just takes a minimally extractive cut. It might not have a choice.

You don’t need to believe that Mark Zuckerberg has become a virtual philanthropist out of the goodness of his heart to believe that Meta will build Metaverse products that create more value than they capture. You need to believe that the rules of the game have changed so dramatically from Web 2.0 to web3 that the long-term profit-maximizing move for the company is to build minimally extractive open and interoperable products that assume that people own their digital assets, identity, and data. If Zuck wants to make sure that he’s no longer dependent on any other platforms, he will need to weaken the power of platforms themselves.

Centralized institutions are losing power to individuals. The institutions that survive will be the ones who accept and embrace that, and adapt their models to fit the new reality. There won’t be a Meta Metaverse; Meta will be one, well-resourced contributor to the Open Metaverse.

Maybe web3’s greatest accomplishment will be that it aligns even Mark Zuckerberg’s interests with the developers, creators, and users who will make the Metaverse what it ultimately becomes.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Thursday,

Packy

*See important disclosures at Masterworks

well-thought out...me thinks ZUCK is far more greedy for power/control/domination

Excellent analysis many thanks. Not sure I understand the notion that competition and portability of assets will keep Facebook (and other Web 3.0 developers) in line. If you create sticky/superior services or DApps for users while making money off the underlying eyeballs/data that is very similar to what resulted in the controversies associated with Facebook and other tech giants in Web 2.0. Lowering switching costs doesn’t necessarily solve the issue or am I missing something?