Welcome to the 665 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 31,114 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday! It’s been a good week. Let’s keep that momentum going!

Sponsored deep dives have become one of my favorite parts of writing Not Boring, and not just because they mean that this newsletter is a financially viable way to make a living (although that part is great!). What I enjoy most is that they give me access to the people building companies that are re-shaping the industries that you and I are interested in. I’m able to write in more depth on these topics with their guidance than I can alone. I know I seem very fancy and cultured, but I didn’t know nearly as much about the art market as you might expect.

Obviously, being paid to write something means that there’s a potential conflict of interest. Earning and keeping your trust is the only thing that keeps this newsletter going and growing, and I’m confident I haven’t written a single thing in a sponsored post that I wouldn’t have written anyway, but I want to give you a peek into my process. You can read how I think about it here:

I told you that I’d let you know how I’m being paid for each sponsored deep dive — CPM (paid a certain rate no matter what) or CPA (paid for each person who signs up for the product). Since I’m writing about an investment product, and this isn’t advice, I’m being paid on CPM.

Today, I’m writing about a company that I’ve written about before. It’s a leader in one of the spaces that fascinates me most: alternative investing. Software is eating the markets, and democratizing previously opaque and inaccessible markets. Maybe no asset class fits the bill better than blue-chip art.

Let’s get to it.

Masterworks: Demystifying & Democratizing Art

The Case of The Missing $450 Million Mundi

In November 2017, Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi became the most expensive piece of art ever when it sold at Christie’s for $450 million. The buyer, at first anonymous, turned out to be Saudi Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud, who was, in turn, allegedly serving as a proxy for Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). When the painting’s planned exhibit at the Louvre Abu Dhabi was delayed indefinitely, it set off wild conspiracy theories involving the Saudis, Russians, and the Trump campaign. According to Vox:

Narativ published a theory that placed Salvator Mundi at the center of an international money laundering scheme implicating the royal families of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, along with Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign staff, the Israeli intelligence firm Psy-Group, and the Russian potash fertilizer magnate Dmitry Rybolovlev, the painting’s previous owner.

Rybolovlev, the Narativ post claimed, put the painting up for auction knowing that the Saudis and the Emiratis would bid for it, artificially inflating its value. Narativ posits the funds from the sale were then funneled to Psy-Group, which, according to a report by the Daily Beast, had ties to the Trump campaign.

That theory has been debunked -- if you’re going to launder money, why do it via the highest-profile art sale in history? -- but it highlights how blue-chip, or investment grade, art has historically been:

Limited to the wealthiest of the wealthy

Shrouded in opacity bordering on mystery

Three years later, half a world away from the United Arab Emirates, another art transaction proved just how much those two things have changed.

I hate to brag, and it feels a bit gauche to talk about this publicly, but we’re all friends here so I’ll tell you: I, like MBS, am kind of an art collector.

I own Agnes Martin’s Untitled #1, Lucio Fontana’s Concetto Spaziale, and, yes, a Basquiat, Loin, which the artist painted in his pivotal year, 1982.

Well, I own a small piece of each, at least, which I bought via the subject and sponsor of today’s essay: Masterworks.

Meet Masterworks

Masterworks, founded in 2017, is the first company to make it possible for everyone to invest in blue-chip art, from Monet to Warhol. It’s a part of the class of startups taking advantage of regulatory and technological advances to bring investing in alternative asset classes to the masses. There’s Fundrise for real estate, and Rally Rd. for collectibles, AngelList for venture capital, and Republic for equity crowdfunding. I wrote about this group in Software is Eating the Markets, saying of Masterworks:

Masterworks takes art collecting digital and makes it accessible to regular investors. Investors can buy shares in works by Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Picasso, Banksy, and Monet. Even a digital portfolio of blue-chip art is more tangible than a bond, is something buyers can brag about to friends, and provides an excuse to learn art history, and returns from blue-chip art have doubled the S&P 500’s over the past twenty years.

Art is the archetypal alternative asset class in a world in which rates remain low and software eats the markets. It provides social status, entertainment, education, and a digital asset that’s beautiful to look at and to display. Plus, unlike, say, Bitcoin, which uses math to create scarcity, each classic piece of artwork is truly one-of-a-kind.

It’s also compelling enough to own that it should attract some retail investment dollars away from stocks and help investors create more diversified and less correlated investment portfolios. In fact, using Masterworks’ data, Citi found that art has a minuscule 0.01 correlation factor with the S&P.

Blue-chip art should be an aesthetically pleasing part of most diversified, long-term investment portfolios, and indeed, art has long been a mainstay in the portfolios of the ultra-wealthy. But until very recently, art investing has been out of reach for the average investor. With art, maybe more than any other asset class, the best investments are often the most expensive, and investing in art, until now, meant buying the whole damn piece.

Masterworks is changing that, and making rare art attainable for regular people. I, for example, write a free newsletter and I own a Basquiat. So with Masterworks’ help, today, I’ll serve as your curator and guide through the wonderful world of blue-chip art.

Masterworks’ Price Database. Masterworks built the most complete repeat-sale pair database, which underpins everything it does.

Art as an Asset Class. Strong returns, low volatility, low correlation, and declining supply.

Digitizing and Democratizing Art Investing. Masterworks gives anyone the opportunity to purchase shares in blue-chip art.

Investing on Masterworks. It took me 15 seconds to invest in a piece of art. I’ll show you.

Art Market Tailwinds. Blue-chip art is a classic investment, and one that should be particularly well-suited for the world today.

Build Your Portfolio. Once you’ve read today’s essay, you’ll get your Art Connoisseur Diploma and can skip the waitlist to start investing on Masterworks.

If you’ve always wanted to invest in art and just want to get to it, you can sign up to start investing on Masterworks right now. Not Boring readers can jump the waitlist at this link:

If you want to sound smart and cultured at your next socially distanced dinner party, put on your top hat and monocle and come explore the wonderful world of art with me.

Masterworks’ Price Database

To understand the art market, we need to start with Masterworks’ Price Database. Much of the data we’re going to use throughout this essay, and Masterworks’ own buying process, is based on the Database. Normally, I would look for data from a diverse set of sources, and I did for this essay as well, but the fact is Masterworks’ data is the most complete picture there is. Even leading investment banks like Citi rely on Masterworks’ data.

So what is it and why’d they build it?

The art market has historically been opaque. If you’re one of the small handful of people in the know, that’s a feature. If you’re putting up your own money to bring art investing to the masses, like Masterworks is, that’s a bug.

Since Masterworks takes principal risk by purchasing works of art itself, and qualifies each offering with the SEC, it needs hard numbers. But hard numbers only existed scattered across old paper auction catalogs, which meant that it was impossible to get a sense for each artist and work’s historical performance. So Masterworks built the world’s most comprehensive repeat-sale pair database in order to understand how the market performs broadly, and by artist and work.

Masterworks’ research team built the Price Database by compiling over 3 million datapoints from over 300,000 auction transactions going back to 1960, often by painstakingly going back through paper auction catalogs by hand. By putting all of that data in one place, and plotting sale prices for paintings that have sold at least twice, they’re able to understand how artists and their specific works perform over time.

This 1982 Untitled piece by Basquiat, for example, has returned 5,286x since its first public auction purchase in 1987 after selling for $110.5 million in 2017, a record for an American artist.

The Price Database is a really fun consumer-facing tool, and the best way for someone who’s more numbers-driven than beauty-driven, like yours truly, to learn about art. Here’s what a search for Monet’s history looks like:

You should go play around with it by searching your favorite artists. Compare Banksy to Monet to Murakami. Read the descriptions of the artists and their work at the top of each page, and then compare paintings by Returns or Sale Price to start to understand which pieces collectors value most.

You’ll notice, though, while you’re exploring, that not every artist or work is in the database. To ensure accuracy and consistency, and to generate a return metric, Masterworks doesn’t include paintings that haven’t been sold at auction at least twice.

For example, when I read about Salvator Mundi, I obviously searched Leonardo da Vinci, but came up empty-handed. I thought there was an error, so I reached out to Jason Papodopoulos, who runs data science at Masterworks to ask about the omission. His answer was more fascinating than I could have hoped for, and I’ll repost it here in full:

Regarding da Vinci, we have not identified any da Vinci auction results except Salvator Mundi, meaning not even works that have been sold once. We have, however, identified multiple works by followers or artists of his circle. His works never come at auction, and when they do, you see what happens.

In the case of Salvator Mundi (see: Christie’s ), its Provenance (list of prior ownership) does mention 2 public sales. One may think that this makes the work a repeat-sale pair. However, a major factor in the Old Masters market is attribution and authentication. In the past, the work was attributed to Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, and was sold for £45. After research, specialists concluded that it was actually a da Vinci. Hence, the assumption that you can calculate the return of a work because an artwork doesn't change is challenged in such cases.

Under our research framework, we do not include works that faced issues with attribution and/or authentication. This is one of the reasons why we are also not involved in the Old Masters market.

There’s so much in that answer. No da Vinci painting has ever changed hands twice in a public auction, and Salvator Mundi is the only known da Vinci to sell at auction. That explains why it was the most expensive sale of all-time. The only other time the work went up for sale at auction, it was actually under another artist’s name, which allowed it to slip under the radar and sell for £45. Once da Vinci was confirmed as the artist, the price shot up over 7 million times!

The answer also shows the rigorous approach Masterworks takes to its price database. It’s more than just a fun and educational tool for exploration; that’s a byproduct. More importantly, it underpins the transformation of the art market from a wealthy collectors’ playground to an investable asset class.

Art as an Asset Class

Art is a $1.7 trillion asset class that most of us don’t think of as an asset class.

It’s also one of the oldest. Before Patrick Drahi (a billionaire art collector, of course) took it private last year for $3.7 billion, auction house Sotheby’s was the oldest company on the NYSE.

$68 billion worth of art changed hands in 2019, but unless your friends are particularly artsy or particularly wealthy, you probably don’t know the people attached to many of those hands. I polled my Twitter followers this week, and only 13% allocate to art.

I asked those who do own art to reply with the percentage of their portfolio they allocate to it, and very few replied… because investing in art is synonymous with being really rich, and no one wants to come out and say, “I’m really rich.” In fact, the first reply to the tweet was, “I’m not rich.”

It’s a shame that art, like many of the best performing asset classes, has been unattainable to all but the wealthiest of the wealthy. Particularly at a time when people are piling into Bitcoin and gold to hedge against inflation with rates at all-time lows, blue-chip art is a smart piece of a diversified portfolio.

According to Citi, “Art could gain increasing recognition as an investment asset class over time given its rate of return and lack of correlation with major asset classes.”

On Panic With Friends, Masterworks founder and CEO Scott Lynn told Howard Lindzon:

We fundamentally believe in this world where just like people have allocations to real estate, they should have some allocation to art. It’s a similar asset class, performance we think is arguably better… We’ve definitely seen more investors on the platform that are just doing it purely based on historical returns and the risk profiles that we publish, and are frankly less focused on the individual art itself. They’re just viewing it as a diversifier to enhance returns on their existing portfolio.

That quote gets at three of the four main reasons that art makes sense in an average long-term investor’s portfolio:

Blue-chip art has historically generated equal or better returns than public equities,

With relatively low volatility,

The lowest correlation to equities of any asset class, and

Scarcity driven by declining supply.

Let’s look at each.

Strong Returns

Blue-chip art breaks down into four main categories: Contemporary, Post-War, Impressionist, and Modern. Contemporary, the best-performing and the main category on Masterworks, has performed well against equities for decades.

Using Masterworks’ data, Citi’s Private Bank showed that the broad art market has, “Risen at an annualized rate of 5.3% since 1985, similar to the return of developed investment grade fixed income (6.5%) and high yield fixed income (8.1%).”

Looking at just the past twenty-five years, Masterworks’ Contemporary Art Index has outperformed the S&P, generating 13.6% annualized returns compared to the S&P 500 Total Return at 8.9%. That sounds like a relatively small difference, but it means that $100 invested in Contemporary Art in 1995 would be worth $2,423 today while the same amount invested in the S&P 500 would be worth $842. That’s nearly 3x outperformance.

Since blue-chip Contemporary art has traditionally been available only to the ultra-wealthy, art has contributed to widening the wealth gap even relative to the roughly half of the US population that owns equities.

Low Volatility

Contemporary art is also less risky than equities, or even housing or gold, as measured by loss frequency and depth over three-year investment horizons.

Since 1995, Contemporary Art has lost money only 4% of the time over three-year periods. When it does lose money, it has lower drawdowns. The maximum annualized loss over three years for Contemporary Art is (0.5%) versus (16.4%) for global equities. The worst year in recent history was 2016, when art prices declined 10-15% due to capital controls in China and Brexit.

Part of that stability is due to who owns art: the ultra-wealthy are less likely to need to sell art when prices drop, so they just don’t sell. Since the market doesn’t open every day, like the market for equities or gold, it makes sense that the drawdowns wouldn’t be as deep. If you owned practically any stock in late February, performance would have looked brutal if you measured performance from March, but would have looked fine if you’d closed your eyes until April.

Even still, for those who are able to allocate a small portion of their portfolio to art with the understanding that they’re going to hold for multiple years, history says that there’s less of a chance of losing large sums of money.

Low Correlation

In Fundrise & The Magic of Diversification, I boiled Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio’s seminal paper, Engineering Targeted Risks and Returns, down to the following sentence:

Allocating money across a diversified portfolio has historically generated better risk-adjusted returns than concentrating in just stocks, bonds, or even the traditional 60/40 split.

People calculate diversification in a portfolio using a measure called the “correlation coefficient,” which quantifies how two assets move in relation to each other on a scale of -1 to 1. A correlation of -1 means that they move in exactly opposite ways: Asset A goes up by $1, Asset B goes down by $1. A correlation of 1 means that they move in lock-step.

In 2019, Citi partnered with Masterworks to measure art’s correlation to ten other asset classes.

Citi concluded that:

Perhaps art’s most attractive investment quality over the long run has been its diversification potential. Strikingly, the broad art market’s highest correlation with any other asset class was 0.34, which was with cash. It has showed low or even negative correlations with many others, including the fixed income asset classes, whose return profile was similar. Adding art market exposure to a portfolio of other assets, therefore, would have helped improve diversification over time.

On The Pomp Podcast, Masterworks CEO Lynn said that if anything, art is most correlated to the concentration of wealth in ultra high net worth individuals’ (UHNWI) hands. It’s also negatively correlated with real interest rates.

Those are two correlations that are perfect for the present moment. Historically, adding art to your portfolio would have improved risk-adjusted returns by increasing diversification, and current conditions seem to support art’s performance more than usual.

Scarcity

Art’s fourth investment characteristic is perhaps its most unique: the supply of works from blue-chip artists decreases over time. The pool of blue-chip artists is small -- according to Artprice, 62% of the $68 billion in 2019 transactions were of the top 100 artists -- and shrinking.

All else equal, lower supply means higher prices. Bitcoin fanatics are enamored of the fact that there is a mathematical limit to the number of Bitcoin that will ever exist. Plus, as the New York Times recently pointed out, as Bitcoin holders lose their wallets or forget their passwords, supply decreases, making the existing supply, theoretically, more valuable.

Art is kind of like Bitcoin in this respect.

Take da Vinci. As Jason pointed out, despite the fact that da Vinci created many works of art in his lifetime, there has only ever been one da Vinci sold at auction.

There are a couple of reasons:

Artists Die. This is obvious, but once an artist passes away, there can never be any other works created by that artist (with the possible exception of Tupac).

Museum Donations and Lost Works. Collectors often donate their collections to museums, taking those pieces off the market for good. Nearly all of da Vinci’s major extant works belong to museums around the world, from the Uffizi in Florence to the Louvre in Paris. Many others are simply lost.

According to the TEFAF Art Patronage Report, Ultra High Net Worth Individuals donated $19.5 billion worth of art to institutions in 2018 alone, cutting the available supply by 1%. While some of these donations come from a place of genuine charity, many are doing it for financial reasons. Artsy points out that donating art is a high-profile way to get tax write-offs against capital gains. After a 2020 in which capital gains for UHNWIs were so high, expect to see more donations.

Because of death and donation, when you buy a de Vinci (or a Basquiat, Monet, or the work of any other deceased blue-chip artist), you can be sure that the supply will remain flat or decrease over time.

Risks to Investing in Art

Those four features -- strong returns, low volatility, low correlation, and scarcity -- suggest that blue-chip art makes sense in most people’s portfolios. It’s not without risks, though. Citi highlights a few key risks that investors should be aware of:

While broad-based indices like the Masterworks.io Total Art Index may be a good representation of the art markets as a whole, investors can’t easily gain that kind of exposure. Portfolio performance is based on what you own.

There’s no established tracking product for art. You can’t buy the equivalent of SPY, the S&P tracking stock, for art.

Art is less liquid than equities or fixed income and more similar to real estate, and requires longer transaction times and higher transaction costs than other asset classes.

Additionally, Artsy’s Martin Gammon writes about the “Dark Matter” of private collections that remain underwater off-the-record, as owners don’t sell losers. That may lead to sample selection bias in which only the paintings that have appreciated show up in the repeat-sales numbers. This 2013 art economics paper provides a good analysis on the size of that effect.

Citi cites one last property of art that’s riskier than equities, too:

Gaining exposure to the art market requires the purchase of physical artwork, with the ‘blue-chip’ segment of the market typically exceeding multi-million dollar price points.

Masterworks is changing that.

Masterworks: Digitizing and Democratizing Art Investing

Until now, art hasn’t really been investible the same way that stocks, bonds, gold, or even real estate are. Buying art has traditionally meant buying a whole piece of art. That’s like saying the only way to invest in the stock market is to buy an entire company.

Sure, you can buy more affordable art, like a print or a piece from a local artist. I’ve bought that kind of art before. But that kind of art is not a good investment. The best risk-adjusted returns are in blue-chip art by artists whose names you’d recognize even if you weren’t that into art. Picasso. Basquiat. Warhol. Haring.

Until now, buying blue-chip art, the kind that exhibits all of the qualities I wrote about above, cost millions of dollars. It was something that regular people never even considered. There’s a reason that so many heist movies are about stealing blue-chip art: some convoluted and complicated scheme was probably the only way that most of us had to acquire it.

Enter Masterworks.

Masterworks is the first platform for buying and selling shares representing an investment in iconic artworks. Founded in 2017, Masterworks takes advantage of SEC Regulation A to securitize works of art and sell shares to regular investors.

Here’s how it works:

Find the Best Artists

Masterworks employs a team of researchers (the crack staff that worked to digitize sixty years worth of physical art auction catalogs to create the Masterworks Price Database), who use proprietary data and models to identify which artist markets have the best momentum. They look at a combination of quantitative and qualitative factors like:

Which artists have a significant enough track record at auction to have meaningful pricing data - less data, riskier artist

Whether there’s a global collector base interested in the artist

The cultural relevance of an artist

How many museums and public collections support an artist

Take it from the Masterworks team (and take notes, these are the best in the biz):

Last year, the team identified 40-50 artists it was interested in buying. Masterworks Target Artists have outperformed even their blue-chip Post-War & Contemporary peers since 1996.

Purchase the Best Art

Masterworks’ acquisition team drills down on the things that drive the price of specific works within target artists’ portfolios:

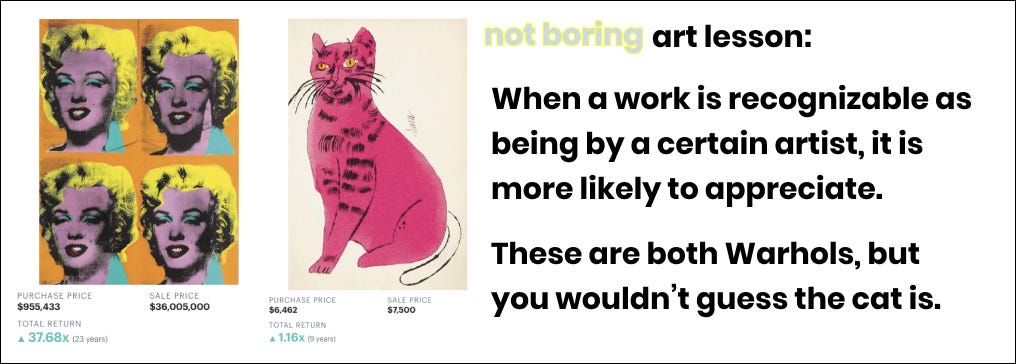

Recognizability. How recognizable is a piece as being by a certain artist. A Marilyn Reversal from Warhol will be worth more than a sketch of a cat, because the former is obviously a Warhol.

Medium. Many artists express themselves across a variety of media, but paintings will typically perform better than sketches or photos.

Size Matters. Typically, the bigger the better. A lot of people who buy art are doing so to show it off, and a larger painting makes a louder statement.

Year of Creation. Artists go through good periods and bad. Basquiat painted Loin, the one I own shares in, in his best year, 1982. That’s the same year he painted Untitled, the skull painting that sold for $110 million.

They then set out to locate the best examples of those paintings currently available at the best prices. They do so armed with Masterworks’ Price Database, offering a more complete comp set than any on the market.

Once the acquisitions team identifies the work, they use Masterworks’ own balance sheet to acquire the painting.

Securitize the Art

Lynn originally came up for the idea of Masterworks during the ICO craze, when people were using crypto to sell shares in all sorts of things, most of them no more than air. He quickly realized that to democratize art legitimately, he needed to work within the regulatory frameworks.

Luckily, under the JOBS Act, regulation moved closer towards giving regular people access to investments previously available to only the wealthiest. Regulation A+, part of the JOBS ACT, is the main piece of regulation that makes Fundrise, Rally Rd., AngelList, and Republic possible.

So in accordance with Reg A+, Masterworks creates a separate LLC for each work that it purchases, registers it with the SEC, and releases an Offering Circular (like a company issues an S-1 before going public). It then sells shares in the LLC, which give each holder ownership of a piece of the LLC that owns the asset.

The fact that it’s regulated offers investors protection. It can’t mislead, and it can’t run away with the paintings. Even its salespeople are regulated by FINRA, the same body that regulates financial institutions.

After issuing the Offering Circular, Masterworks launches the offering on its website. That’s where we come in.

Investing on Masterworks

On Masterworks, anyone can become an art investor.

Once you sign up for Masterworks (and skip the 25,000-person waitlist with the Not Boring link), you’ll schedule a call with someone from the Masterworks team who will get a sense for your goals and risk appetite, and answer any questions you have about purchasing shares on Masterworks.

From there, buying a share in a piece of art on Masterworks is really easy. In the middle of writing this, I got an email from Masterworks: “Invest Now: Fontana (15.3% historical appreciation).” I clicked to learn more, got an overview of the painting, and read Masterworks’ thesis. If I wanted to, I could read the full Offering Circular, the Reg A equivalent of an S-1 for art.

Then, just to show you how fast the process is, I recorded a gif of myself going from Overview to purchase.

Within the 15 second gif limit (after doing my research, of course), I bought shares in a work of blue-chip art. How cool is that?

Each share in a primary offering costs $20, and I can buy as many or as few as I’d like from the available supply. Once I own shares in paintings, there are two ways I can make money:

Masterworks Sells. Masterworks plans to hold paintings for 3-10 years, monitor the market, and sell when the artist or comparable works are performing well. At that point, Masterworks takes its fees - like a hedge, PE, or VC fund, it takes 1.5% annual management fees and 20% carry.

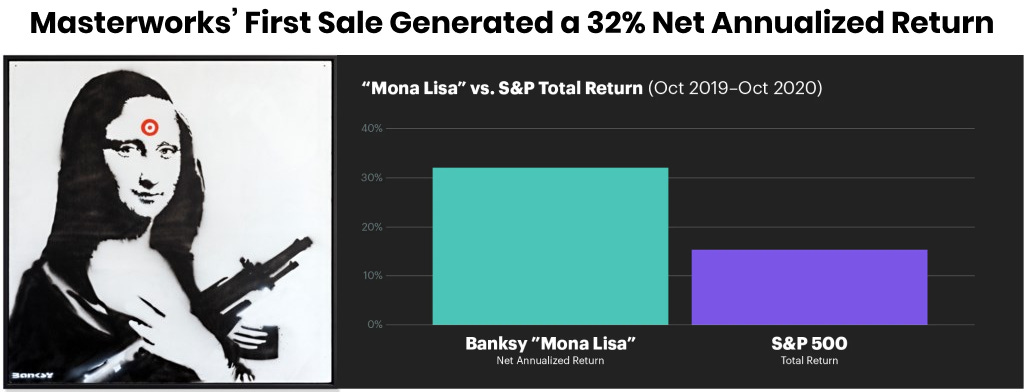

This isn’t just theoretical. In October 2020, Masterworks sold Banksy’s Mona Lisa for $1.5 million after offering the painting to Masterworks investors the prior October at $1,039,000. Mona Lisa was the second work that Masterworks offered and the first painting it sold, netting investors a 32% Net Annualized Return.

Secondary Market Trading. In 2020, Masterworks launched a secondary market in which buyers and sellers of shares of art offered on Masterworks can trade with each other. That means that if you missed an offering, you can buy shares from someone who owns them, and if you own shares and don’t want to hold until Masterworks sells, you can get liquidity from other members.

Currently, Masterworks members are offering shares in works by Monet, KAWS, Banksy, Cecily Brown, George Condo, and Warhol, at prices set by the people offering them. Among the current offers, markups to the original $20 purchase price range from 1% to 8.75x for earlier offerings, including the first work sold on Masterworks -- Andy Warhol’s 1 Colored Marilyn (Reversal Series) -- and Banksy’s Monkey Poison.

Beware: buying art on Masterworks is a little bit addictive. I’ve bought shares in each new offering since signing up late last year. It’s an addiction I’m comfortable with, though, because I think the art market is set to benefit from the convergence of some major trends.

Art Market Tailwinds

The art market, which has already outperformed other asset classes, has some serious tailwinds behind it that are set to expand the demand pool, while the supply of investment grade art, as we now, as new art scholars, know, declines.

First, there are the macroeconomic factors. Interest rates are at all-time lows and likely to remain there for a while, UHNWIs hold more wealth than ever before, and there are trillions of dollars seeking anything that will give them safe returns above the rate of inflation. Art, historically, has fit that bill.

Second, if Masterworks is successful in democratizing access to art at scale, both by allowing regular people to invest and by helping institutions view art as an investible asset class, it will expand the amount of dollars seeking the same supply of blue-chip art. Imagine if only the world’s billionaires could buy stocks -- not even hedge funds, or banks, or endowments, let alone retail investors -- and then all of a sudden, everyone could buy stocks. The rush in won’t be as violent as that would be, but a similar dynamic should play out on a slower, smaller scale.

Third, art is the perfect asset for the type of investing that is becoming increasingly popular, the type that I wrote about in Software is Eating the Markets.

While Masterworks highlights art as a useful slice of an intelligent portfolio, I think it’s more than that. It has each of the characteristics that retail investors care about when they buy an asset.

Social Status. Owning art has always been a status game. While buying shares in a work of art doesn’t confer quite the same status boost that buying a whole multi-million dollar painting does, there is still an aura around art that makes those who own and understand it seem sophisticated and cultured. Online or in-person, knowing the difference between Monet and Rembrandt or KAWS and Kusama says something about you.

Education. One of the things that I enjoy most about investing is that it forces me to learn. I never took an art history class in college; it seemed too subjective, too complex to just casually understand. But attach a price to something and allow it to move with the market? I’m in. Even just buying shares in a few paintings on Masterworks taught me more about art than I ever thought I would care to learn. Did you know, for example, that Impressionist artists’ paintings only appreciate in line with the rate of inflation, partially because their style has gone out of... style?

Entertainment. It’s hard to imagine tens of thousands of people getting excited about something as otherwise dry as a company releasing a spreadsheet full of numbers every three months without owning stocks. Art is naturally entertaining -- millions of people who don’t own art go to galleries and museums every year -- but owning shares in certain artists’ works means that every auction and new exhibit involving that artist is an event worth following.

Digital Asset. Right now, this is the least developed of the four, but I think there’s a ton of potential here. I’m spitballing (read: this isn’t coming from the Masterworks team), but I could see Masterworks giving each investor on the platform their own public-facing gallery showcasing the pieces in which they own shares. They could even offer digital art backed by Non-Fungible Tokens to each investor in a work, giving them ownership of a digital asset tied to the physical one.

Ultimately, in a world in which alternative assets are gaining tremendous popularity, art’s unique characteristics make it the perfect asset for a new generation of investors. Those three factors -- macroeconomics, democratization, and Software Eating the Markets -- should combine to drive up the price of the very best art, and with its data and expertise, Masterworks will be the first to know.

Build Your Art Collection

Congratulations! You’re an art connoisseur now.

Next time you’re playing trivia, you can answer “What was the most expensive work of art ever sold?” with confidence, and give the wild backstory. You know all about art as an asset class, down to its correlation with the S&P. You understand what makes art valuable, and which pieces by which artists have gained the most value over time.

And now, unlike any other time in the past century, you’re able to invest in blue-chip art without putting up millions of dollars to purchase an entire painting.

So put your newfound knowledge to use. Go to the Masterworks Price Database and explore. Search your favorite artist to understand how their works have appreciated over time. Compare Banksy to Basquiat. And please, take your top hat and monocle off. You can finally be an art investor without being a snob.

As a Not Boring reader, you can skip the waitlist and start investing in rare art now.

Important note: this is not investment advice. Please do your own research before considering investing in art or any other asset class mentioned in this piece.

Thanks to Dan and Puja for editing, and Michael and Scott for partnering with me!

That’s all for this week! We’ll be back next week with two topics I’m giddy to explore.

Have a good life, we’ll talk to you soon,

Packy