Gone in 60 Quibis

The Eagerly Anticipated Follow-up to Shotcallers v. Worldbuilders

Welcome to the 96 new subscribers since Monday’s e-mail! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed yet, it’s easy! Just sign up, sit back, and enjoy, and maybe even learn a little bit.

Hi friends 👋🏻,

Happy Thursday!

I set a goal to get to 1,000 subscribers by the end of quarantine, and we blew through it on Tuesday 🎉 Thanks to all of you for making that happen. I hope you’re having as much fun as I am.

Today’s post is a follow-up on Monday’s Two Ways to Predict the Future. If you haven’t read that, start there and then come on back.

With that framework in place, we can do something super fun and en vogue in the sophisticated guise of a strategy discussion: dunk on Quibi.

Gone in 60 Quibis

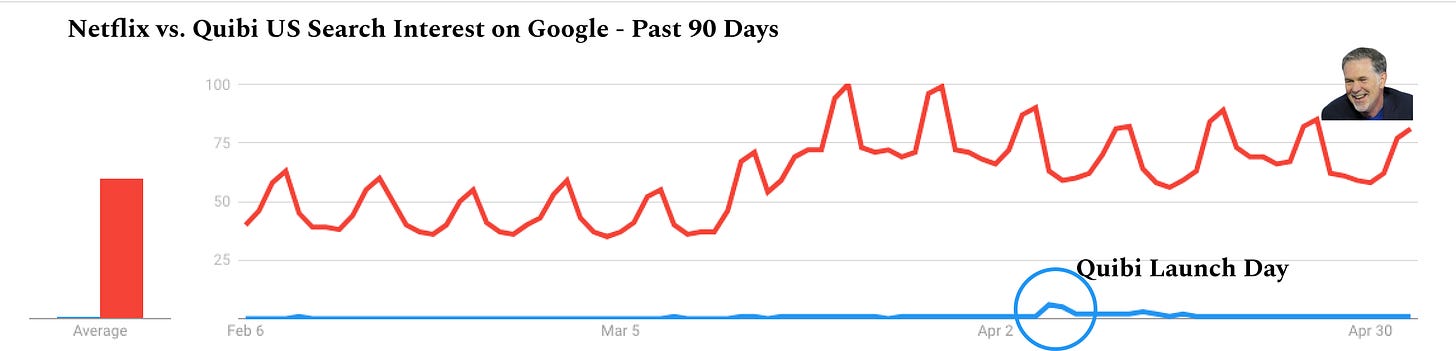

Netflix and Quibi are competitors in the Streaming Wars, the battle to get all of us to pay a monthly subscription to watch streaming video. Netflix has been at this for 23 years, building its way up from a DVD delivery service to a full-stack studio/distribution/technology powerhouse. Quibi celebrated its one month anniversary yesterday, and it is struggling. The Shotcaller vs. Worldbuilder framework can explain why one is succeeding while the other is the butt of countless jokes, like this funny one that I made:

The best jokes are the ones you need to explain. So let me explain Quibi.

Quibi is a mobile streaming company founded by former Disney Chairman and Dreamworks co-founder, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and former eBay and HP Enterprise CEO and California gubernatorial candidate, Meg Whitman.

Quibi, short for “Quick Bites,” creates maximum 10 minute mobile-only video content for millennials. Unlike YouTube or TikTok, it’s Hollywood-level production with expensive Hollywood talent.

Quibi has raised $1.75 billion, which Divinations argues is just table stakes in the streaming against with Netflix, Apple, Amazon, Peacock, Disney, HBO, etc.

Quibi said it would spend $470 million in marketing in the first year.

Quibi generated 300k app installs on its launch day, compared with 4 million installs for Disney+ on its own. That day, it was the 4th ranked free app in the Apple App Store. As of a couple of days ago, it was at #159, just below the Silicon Valley powerhouse: Lowe’s Home Improvement App.

Two weeks ago, Quibi’s most senior marketing exec left. A week ago, it caved and put some of its shows on YouTube. On the same day, a report revealed that it was leaking data to advertising and analytics companies.

On Monday, activist hedge fund Elliott Management financed a lawsuit against Quibi by Eko, claiming that Quibi violated Eko’s patents and stole its trade secrets in building Quibi’s one cool feature, Turnstyle.

Just one last piece of info: in its advertising, Quibi has tried to turn “a Quibi” into a unit of time somewhere south of 10 minutes. As in, “Popping out for a walk, I’ll be back in a Quibi!”

Back to the joke. A month after launch, it seems like Quibi is dead. Gone in 60 Quibis. Get it?

Anyway, dunking on Quibi just to dunk on Quibi would be mean, and it would be tired. People have been predicting Quibi’s demise since it was but a gleam in Katzenberg’s eye.

I’m dunking on Quibi for a reason. Comparing Quibi and Netflix is the perfect way to explain the difference between Shotcallers and Worldbuilders.

Netflix: From Red Envelopes to Envelopes Stuffed with Cash

Long before its successful foray into streaming, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings showed his Worldbuilding skills by betting on the future of another unproven technology: DVDs.

Hastings and his co-founder, Marc Randolph, launched Netflix as a DVD sales and rental company. At the time, DVDs were a brand new, tiny market. Only 437,000 people bought a DVD player in 1997, the year that both Netflix and DVDs launched in the US. But the economics worked, so Hastings and Randolph went for it.

At first, DVD sales made up 97% of revenues. The co-founders realized, however, that DVD sales were an undifferentiated business in which Amazon and Walmart would crush them. They scrapped the sales business to focus on the more defensible rentals, limiting the market even further.

Focus allowed Netflix do rentals really well, and the business grew. At the same time, the market was already eagerly anticipating streaming video, which Hastings and Randolph knew was years away from being viable.

They realized that instead of becoming the best at delivering video content through either DVDs, which was great in the present but terrible for the future, or streaming, which would be great in the future but wasn’t ready in the present, they needed to position themselves as the platform-agnostic best way to find the movies you love.

The most important thing they did to make that happen was building Cinematech, which would become Netflix’s fabled recommendation algorithm. That served the company well in DVD rentals while positioning it for success in streaming, and ultimately, in creating its own content.

It worked.

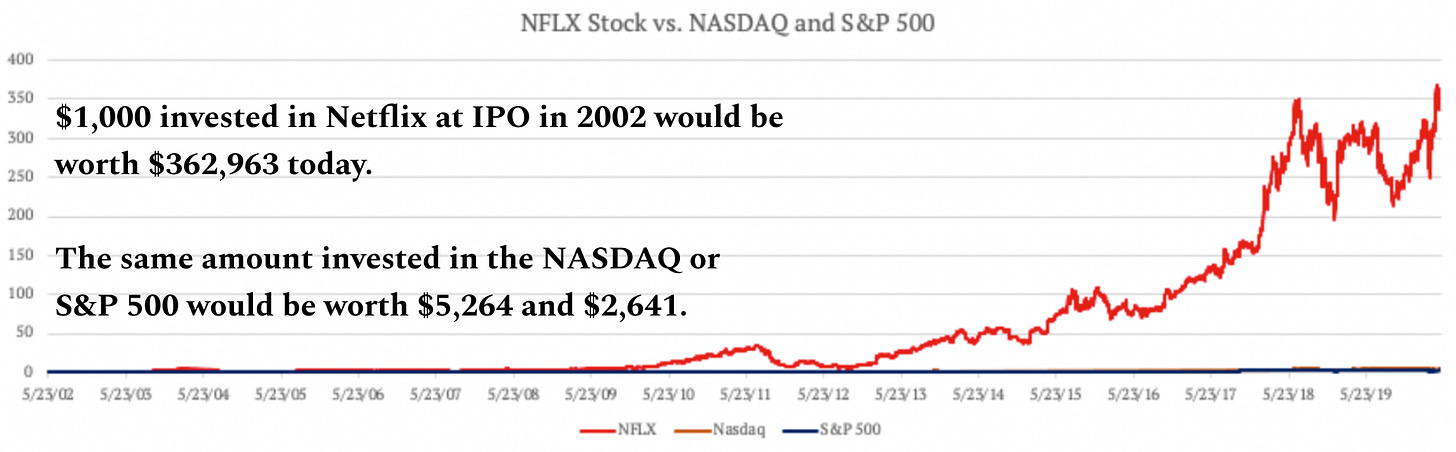

At the turn of the millennium, Netflix had 110k subscribers and sent DVDs to your house in little red envelopes. Today, Netflix spends $17 billion creating its own content and serves 182 million subscribers worldwide across 800+ devices.

If you had invested $1,000 in Netflix at its IPO in 2002, it would be worth $362k today.

Netflix used a tiny piece of the video sales and rental market as a wedge into the bigger opportunity of delivering consumers video based on a deep understanding of their preferences. They started small to become massive.

By building strategically from humble beginnings over the past 23 years, Netflix has built a moat comprised of advantages in technology, personalization, a deep library of licensed and original content, the ability to amortize new content over a large and growing subscriber base, and distribution.

Reed Hastings is a Worldbuilder.

Quibi

And then there’s Quibi.

Quibi is what you get when veteran tech and entertainment industry execs look at a bunch of stats about Millennials, Snapchat, mobile usage, Netflix, podcasts, and a bunch of other buzzwords and decide to brute force spend and connection their way into a product that ticks all of the boxes. It’s “movie-quality shows designed for your phone” featuring famous celebrities, aimed at a phone-addicted generation.

Unlike Netflix, Quibi is explicitly focused on one format - mobile - and one content type - well-produced short-form. They solve for one Job to be Done: something to watch while commuting or waiting in line.

But there’s a problem Quibi’s approach to doing that job: we don’t do any one thing on our phones for 6-10 minutes straight. Podcasts are great because I can listen while checking my e-mail or scrolling Twitter. Video, on the other hand, commands my full attention. No matter how well-produced the content or who’s in it, I’m switching apps as soon as I get the notification that someone followed me on Twitter. I do longform on my computer and I do ADHD on my phone.

In addition to being out of touch with your target market, one of the challenges you face when you’re two seasoned vets with a combined $5 billion net worth is that at that point, you can’t start small. You can’t pick a clever wedge and patiently grow. You can’t spend years waiting for a master plan to fall into place. You can’t, in other words, be a Worldbuilder.

Instead, like a cocky quarterback, Quibi tried to call its shot. It saw a massive and obvious market, video streaming, came up with a moderately differentiated value prop, and tried to spend its way to victory. Blending metaphor and reality, it even bought a Super Bowl ad.

(A $5.6 million commercial about a bank heist from a company that raised $1.75 billion and hadn’t yet released product is so on the nose and easy to make fun of. I’m just going to leave it.)

Quibi isn’t starting small and growing into a big market. It is spending a ton to acquire customers into a business with no real moat and competition on all sides. And it is building a product that no one seems to be asking for. At the low-end, YouTube and TikTok have good enough content, and if we can’t sit still enough to watch a 10-minute video all the way through on our phones anyway, why not watch a 30-minute show on one of the many platforms we already use.

Thus far, Quibi does not look like it will be a successful Shotcaller like Joe Naimath, Mark Messier, or Muhammed Ali. Quibi is the worst kind of Shotcaller - a wrong one.

Quibi is the latest in a line of failed Shotcallers like:

Carlos Zambrano, the Cubs pitcher who guaranteed a World Series victory in 2007 (they didn’t)

Rex Ryan, the Jets coach who predicted a Super Bowl victory in 2011 (they didn’t make the playoffs)

Dan Gilbert, the Cavs owner who said his team would win an NBA Championship “BEFORE THE SELF-TITLED FORMER 'KING' WINS ONE” with the Heat (caps his; lol)

If early trends are any indication, Quibi is going to go the way of so many Shotcaller startups - spectacular, expensive failure.

It’s easy to blame the Coronavirus for what’s happening to Quibi. We don’t commute, we rarely stand in line. That’s when we were supposed to be watching Quibi!

But the fact of the matter is, Quibi tried to skip all of the hard stuff that is takes to build a business with sustaining advantages.

If only Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman had subscribed to Not Boring, they could have done this:

That’s the beauty of a good framework. It can save you years worth of heartache in a Quibi.

If you enjoyed that analysis of Netflix vs. Quibi, do me a big favor and share it with a friend.

How to Spot a Fake

I was going to write about a company that I had originally thought was a Worldbuilder before digging a little bit deeper and realizing that they had actually pulled a post-hoc “we meant to do that.” Then I realized that I actually like the product and company, that companies evolve, and that their inability to perfectly predict the future is not a reason to put them on blast. Faced with this choice…

I decided to not be a dick.

But I still think it’s useful to figure out how to spot a fake. You’ll hear or read a company say something like “When we started this company five years ago, we knew that by starting with [X small thing] and making our customers happy, we would one day be able to [do Y big thing]. It’s wonderful to see our plan start to pay off.”

The cool thing about being alive in 2020 (optimism!) is that there’s a record of everything. If you’re as into this stuff as I am, when you hear a statement like that, you can:

Google "[Company Name] Launch Announcement” or “[Company Name] Series A” or something that will return articles on Company A’s early days.

Scan the article to find quotes from the founders or investors on why they’re excited about the long-term vision.

Assess whether the company:

A. Predicted what they ended up doing.

B. Might have had the plan all along but was keeping its cards close to its chest

C. Had no idea that they were going to end up where they ended up and decided to make up a clean story after the fact.

Don’t do this to be a dick or to put companies on blast. Plenty of successful companies have made it through a series of reactions, iterations, and pivots. Learning while you go is a great thing.

Do it because you want to know whether a particular CEO is actually a Worlbuilder. In this context, past ability to Worldbuild is a good predictor of future ability to Worldbuild. When you find a Worldbuilder that survives this stress test, figure out how to join or bet on it as it shapes the future.

Your Favorite Worldbuilders

On Thursday, I asked you for your favorite examples of Worldbuilders in business and in sports and pop culture. I’m sharing a few of the best, starting with someone I think has the chance to be a Worldbuilder by starting with a humble wedge to change the way offices are built.

Brian Chen - CEO, ROOM

Favorite Worldbuilder: ROOM 😎💪🏻

Initial market is the very humble office phone booth. Problem of office build-out is a wicked one that as you know involves a tangle of stakeholders from landlords to general contractors to facilities managers and furniture dealers.

The end goal is a new paradigm for building out offices that fundamentally changes the way that commercial real estate operates (tenant improvements, fixed construction, 10 year leases, etc.) and the way that we work.

Nikil Konduru - Investor, Nyca Partners

Favorite Worldbuilder: V G Siddhartha, Café Coffee Day

He had the rare combination of larger than life vision and indefatigable execution. For more than a billion Indians he turned coffee from a lowly export commodity into a modern Indian cultural artifact that an entire industry could be built around.

Eric Jorgenson - Product Strategy, Zaarly

Favorite Worldbuilder: Ray Kroc, McDonald’s

Invented "Fast Food" as a category, taking the inventions of the McDonalds brothers and seeing an enormous vision for expanding it.

Cultural Worldbuilders: Barstool Sports, Arnold Shwarzeneggar, Kim Kardashian

Links & Listens

🏙 Walt Disney - The City Architect | Suthen Siva

Along with David Perell, Suthen ran the Write of Passage Fellowship that I am a part of while writing an excellent essay of his own. His essay describes how Walt Disney was both a figurative and a literal Worldbuilder. If Disney had been able to design all of our cities, they would be much more … magical places than they are today.

Bonus: Walt Disney is Brett Jaffe’s favorite Worldbuilder

🔮 How to Build a Breakthrough | Mike Maples Jr.

Tina He sent this over after reading Monday’s newsletter, and it’s an excellent companion piece to Two Ways to Predict the Future. Early stage investor Mike Maples Jr. writes about the process of Backcasting - instead of starting today and making projections, start with what the future might look like and work backwards. It’s kind of a how-to manual for Worldbuilding.

👾 The Minimum Viable Metaverse | Marc Geffen

The metaverse - where “citizens jack-in and roam a parallel reality with video game topography” - has long been prophesied by technologists. Geffen argues that we are already kind of living in it. He previews three things that will happen in the near future to usher in a richer quotidian metaverse:

Video games will guide the way

Spatial software is coming soon

The Metaverse will rise out of abstraction & intersectionality

Geffen is a really talented writer. He makes the complex seem straightforward, and uses charts and images to clarify. 👀 for more from him in your inbox soon.

♻️ Don’t Waste the Reboot | The Yak Collective

As the son of two Indie Consultants, I loved this presentation by The Yak Collective, a group of very online independent consultants including my friends Paul Millerd (a Lead Editor on the presentation) and Tom Critchlow. The presentation offers “25 creative and unexpected provocations, ideas, and action frameworks to navigate the Covid-19 crisis.” I particularly like the idea that traditional consultants are like LinkedIn and Indie Consultants are like Twitter.

That’s what I try to do with the Not Boring newsletter - combine more traditional concepts and frameworks with some weirdness to make learning more fun.

Paul Millerd, who I mentioned above, wrote in his newsletter, Boundless, that “Packy McCormick seems to be having more fun than any newsletter writer right now.” This isn’t a competition, but I am.

It’s a blast to get to write to you a couple of times a week in a big blend of all the things I’m interested in, and it’s been so exciting to see so many new people sign up to come along for this ride. Since last Thursday’s e-mail, 221 new smart, curious people have joined us!

We hit the 1,000 subscribers by end of quarantine goal with room to spare, so let’s up it: I think we can get to 2,000 by June 15th.

Ask Puja - nothing gets me more excited than getting a new subscriber e-mail. If you know someone who loves learning about business and tech trends and likes getting a little weird, invite them to join this nerdy party 🤓🎉

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Excellent post. Going to re-read it later.

Also, might be a trivial point, but Quibi is possibly the dumbest brand name I’ve heard in a long time. It means nothing, it’s hard to know how to pronounce or spell it, and it reminds me of “quibble”, which hardly seems like a good brand association.

In my view, the decision-making apparatus that allowed a multi-BILLION-dollar startup to launch with this name is probably responsible for a bunch of other dumb choices that sank this company before it started. I suspect that decision-making-process is something like “no one knows how to tell the billionaires no”, but who knows.