Cityblock Health

The Vertically-Integrated, Value-Based Arbitrageur Fixing Healthcare

Welcome to the 585 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since Monday! Join 56,218 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is a Sponsored Deep Dive on…

Cityblock is solving huge challenges that make a difference in peoples’ lives, at scale. They’re growing fast and hiring across tech, product, operations, finance, legal, real estate, and more.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Healthcare has always scared me, both as a patient and as an analyst. I don’t go to the doctor nearly enough (read: ever) and I’ve only covered one healthcare company in Not Boring, Kenya’s Antara Health. But when Cityblock Health co-founder Bay Gross reached out to me to talk about a piece, I was very curious.

First, because healthcare was a blind spot of mine, and it’s too important not to understand. Many of the next decade’s biggest innovations, and returns, will come from healthcare.

Second, because unlike many healthcare companies, I’d actually heard about Cityblock, and heard good things. It was born in 2017 in DUMBO, a short walk from my Brooklyn apartment, spun out of Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs. I have smart friends who work there. I knew it was building something ambitious, and something in healthcare, but I just didn’t know what, exactly.

Third, because of the money. Cityblock has raised $462 million from very smart investors, including Alphabet, Thrive, Redpoint, General Catalyst, and Tiger.

When I talked to Bay and co-founder Toyin Ajayi, I knew I had to write about the company. It’s a healthcare company that’s doing a lot of things we talk about in Not Boring and helping a segment of the population that’s often overlooked by startups.

Today’s post is a Sponsored Deep Dive -- you can read more about how I select which companies to work with here -- but it’s different than a normal Sponsored Deep Dive. Cityblock doesn’t want you to buy anything; it gets its members from payers. They just want to make people in tech aware of the hard problems and huge opportunities involved with what they’re doing. They want smart, talented people to come join them in helping make healthcare equitable and accessible, and luckily, Not Boring readers are all smart, talented people. Check out Cityblock jobs here.

Let’s get to it.

Cityblock Health

In June 2017, Keith Rabois tweeted the formula for startup success:

Three months later, in September, inside Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs, co-founders Iyah Romm, Dr. Toyin Ajayi, and Bay Gross, launched Cityblock Health.

Coincidence? Yes, almost certainly. But what they’re doing fits Rabois’ formula pretty darn cleanly:

Large Market: Cityblock is operating in a $613.5 billion market. Its market represents 3% of US GDP.

Highly Fragmented: Not only was the industry itself fragmented, but the pieces needed to deliver an impactful experience to customers were fragmented.

Low NPS: The industry hadn’t even tracked NPS, and customers hated the experience so much that they often avoided it unless they absolutely had to use it.

Have you guessed the market?

It’s Medicaid and people who are dual-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Cityblock Health works with some of the most at-risk, medically complex, lowest-income people in the country to deliver comprehensive care that addresses the tangled web of root causes that leave them coming back to the ER time and again, and leave taxpayers footing the ballooning bill.

To fix the market, improve peoples’ outcomes, and save payers (insurance companies and governments) money, Cityblock is taking an approach that’s as vertically integrated as it gets.

The three biggest drivers of healthcare costs are unmet medical, mental health, and social needs, which express themselves as high medical bills when it’s too late. Existing providers treat medical and mental health separately, and don’t deliver social care at all. They wait for the sequelae of unmet social needs to wash up on the shores of the emergency room and then treat symptoms with expensive and avoidable medical interventions.

What does that look like in practice? Maybe the person who is food insecure develops dangerously low blood sugar, which causes a fall, which lands them in the emergency room. Instead of feeding people and educating them on how to manage their needs within the community, traditional healthcare waits until the fall, calls 911, and delivers thousands or tens of thousands of dollars worth of medical care. It’s a tragic game of whack-a-mole.

Cityblock is taking a holistic, vertically integrated approach, addressing the medical, mental, and social needs of its members, treating them like whole people.

It has physical clinics, teams full of primary care providers, pharmacists, psychiatrists, therapists, geriatricians, social workers, and other care providers on staff (with equity and Slack access), and a growing tech team building custom tools to scale Cityblock’s approach to millions of members.

For both sides of the market -- patients and payers -- neither of whom is happy or thriving right now, Cityblock Health is simplifying the value prop.

To payers, it’s saying: give us your most challenging patients at a fixed price, we got this.

To patients, it’s saying: anything you need to improve your life and health, we got you.

Cityblock is exploiting two arbitrages for good: an experience arbitrage that allowed them to see opportunity where others didn’t and a care delivery arbitrage through which they deliver lower-cost care upstream to save on expensive costs downstream.

Healthcare seems scary because it’s regulated and slow and there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. Medicaid and low-income Medicare patients seem like a particularly difficult group to target. But really, Cityblock Health’s approach isn’t different from other companies, like Opendoor, that realized that the only way to win large, fragmented, atoms-based markets was to go vertically integrated, powered by a combination of experienced humans, strong operational systems, and technology.

If it succeeds, Cityblock Health will have solved one of the biggest challenges out there: how to provide quality care to low-income people who need it most and halt America’s ballooning healthcare costs.

This is a big enough opportunity, and fascinating enough business, to get investors excited. In the past seven months, Cityblock raised $352 million in two rounds, $160 million at a valuation north of $1 billion led by General Catalyst in December 2020, followed quickly by $192 million at a healthy step up valuation led by the one-and-only Tiger Global in March.

It’s also a big and important enough opportunity to cure my healthcare-phobia, and digging in, while the product is different than the startups I’m used to covering -- Cityblock is literally keeping people out of the hospital and saving lives -- the things that make the company tick are the same: big market, business model with positive unit economics, and an innovative product, powered by technology. We’ll use that framework to understand Cityblock:

The Market: Demystifying Medicaid.

The Business Model: Value-Based Care.

The Product: Treating the Whole Person.

Strong Early Results

Challenges

The Future of Cityblock, and Healthcare

It all starts with tackling a challenge very few startups have ever dared to face.

Demystifying Medicaid

There may be no category with a higher TAM:Funding ratio than Medicaid.

Medicaid is the joint state-federal health insurance program that provides coverage to millions of Americans including low-income people, children, pregnant women, and people with disabilities. Today, there are 72.2 million Americans on Medicaid, including 50% of all babies born in the US and one out of every three New Yorkers.

In 2019, state and federal governments spent $613.5 billion on Medicaid, and according to a Pew report, many states spend 20-25%+ of their revenue on Medicaid, representing billions of taxpayers’ money. The averages even obscure the extremes; in Massachusetts, that number is over 50%.

From the outside, Medicaid is hairy and scary. It’s a lot of things that startups like to avoid: regulation, government, healthcare, and low-income populations. Plus, dealing with Medicaid has a built-in CAC:LTV challenge. On the CAC side, Medicaid patients are harder to find and sign up than Medicare or commercially insured patients -- statistically, they move addresses more often, and are significantly more likely to be homeless. Medicaid populations often face significant structural barriers when it comes to receiving regular preventative doctor visits:

They may live in primary care deserts

Face transportation barriers and childcare barriers

Lack of employment hours flexibility

On the LTV side, if things go really well, and patients’ lives improve, they may cross the poverty line and churn out of Medicaid. That’s the dating app problem: success leads to churn.

Still, the lack of funding in Medicaid relative to Medicare is stark. Before Cityblock launched, the team identified about $3-4 billion in recent VC funding that had gone into startups tackling Medicare, which covers older Americans, but only $20-30 million in VC funding for Medicaid startups. Medicare is a slightly larger market -- $799 billion versus $613.5 billion in 2019 -- but that doesn’t explain the two-orders-of-magnitude funding gap.

With all other variables accounted for, it seems that the low-income piece accounts for the gap. Which, as a healthcare outsider, seems a little crazy. It’s all the same payer. The government pays for Medicare and it pays for Medicaid. It shouldn’t matter who the ultimate recipient of the care is if Uncle Sam and his Stately progeny are footing the bill.

This is Cityblock’s first arbitrage: deeply understanding an opportunity that others missed.

Most founders, and certainly most investors, are unfamiliar with Medicaid. VCs aren’t typically on Medicaid. They don’t know many people on Medicaid. In a 2017 article titled “Silicon Valley is too focused on taking the easy path in healthcare,” Christina Farr wrote:

Health care startups face regulatory hurdles, long sales cycles and a high burden of proof — and that means it can take more than a decade to make a return. As a result, many venture-backed entrepreneurs are looking instead at opportunities on the fringes of the health care system, such as cash-only health services that don’t require insurance or tests and apps that aren’t regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

It’s easier to focus on consumers who are able to pay out of pocket and deliver unregulated point solutions. That approach is similar to most of the other categories in which startups thrive. Medicaid seems incredibly foreign and hairy and unprofitable in comparison. But Cityblock’s founders are intimately familiar with it. Toyin Ajayi, Cityblock’s President, spent more than a decade working with vulnerable Medicaid patients. Co-founder Bay Gross told me that Toyin “is a top ten expert in the country for behaviorally complex Medicaid groups.”

Complex is the medical term, and it’s also an understatement. Cityblock works with the highest-risk portion of the population, people whose medical and social complications feed off of each other. In their flagship Brooklyn market, the average member:

Has 8-10 diagnoses at any given time

Is on upwards of 12 medications

80% don’t live with nuclear family members in the same household (low social support structures)

20% are housing insecure

Almost all have experienced trauma and/or other behavioral health challenges

Tragically, these New Yorkers are falling through the cracks, and getting left behind. That’s a failure on society’s part, and it’s costing society in equal measure. While investors may not have been paying attention to Medicaid when Cityblock got started, they’re certainly familiar with one important dynamic at play: power laws.

The most expensive 5-10% of the population drives 60% of the costs. These individuals are in and out of the ER all of the time, and they’re disengaged and mistrustful of the system (for good reason!). “They don’t like going to the doctor,” Toyin told me, “because the doctor makes them feel like shit.”

In Antara Health, I wrote about the Vicious Cycle of Uninsurance:

In Kenya, where only 2.8% of the population has health insurance, people avoid going to the doctor to avoid paying out-of-pocket costs, which means that they don’t catch things early, which means they don’t go to the doctor unless things are really bad, at which point out-of-pocket care is so expensive that it’s likely to push those who need to pay for it into poverty.

There’s a very similar dynamic at play here, only the payer is different. In the US, Medicaid and low-income Medicare recipients face a host of issues that combine to make them avoid the doctor. They may be housing insecure, behind on their bills, confused about how to work with the medical system, and work multiple jobs to stay afloat. There’s no time for the doctor, particularly when that doctor won’t address the root issues anyway, and when, as Toyin told StartUp Health, the “person leaves feeling judged and unable to explain that they eat McDonald’s three times a week because they can’t afford to buy leafy vegetables.”

Plus, because Medicaid is a hassle for doctors, many just don’t accept it, which makes it even harder for Medicaid recipients to find someone to treat them. A NBER paper released in April found that billing and administration hassles caused doctors to miss out on 16% of Medicaid revenue, versus 7% for Medicare and 4% for commercial payers. That may be another reason that startups don’t focus on Medicaid. A 16% revenue loss rate is awful in any industry.

This all combines into the Vicious Cycle of Low-Income Healthcare in the US.

The system is broken, inefficient, and ineffective. Paying a lot of money at the bottom of the vicious cycle is expensive, and it doesn’t fix any of the issues that got the person there in the first place.

To fix those issues, you need to rebuild the whole system.

The Business Model: Value-Based Care

One way to try to serve individuals on Medicaid is to work within the system by fixing one thing at a time. Maybe you build clinics, like a One Medical for Medicaid, that treat patients where they are. Maybe you build apps that make it easier for people on Medicaid to communicate with their doctors. Maybe you try to provide healthy meals in the communities in which people on Medicaid live.

Those solutions all sound good, but they’d all fail. The financial incentives are too far out of whack for any one player to sustainably make an impact, and as highlighted above, even collecting revenue from Medicaid can prove to be a challenge.

What if, instead, you said, “Fuck it. Hey states and insurers, just give me all the money you’d spend on Medicaid patients upfront, and I’ll do the whole thing myself.”

That’s essentially what Cityblock does. It’s called value-based care, and the way Cityblock does it is vertical integration to the extreme. If Cityblock makes patients healthier, it makes money. If it doesn’t, it loses money. It’s fully up to Cityblock to figure out how to spend the money in the way to maximize outcomes and lower costs.

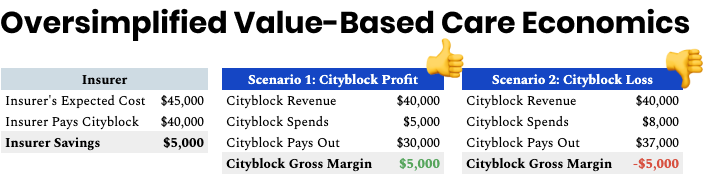

Here’s how it works:

It costs states and insurers a certain amount on average to care for its highest-risk Medicaid patients, say $45k per patient per year.

Cityblock works with states and insurers to find the highest-risk people that it can help, and insurers pay Cityblock a certain amount, call it $40k per patient per year, to take full responsibility for those people. (This is called a capitation payment.)

Cityblock spends some amount on services that it provides to improve the patient’s health and life, and pays out some amount to hospitals and other care providers.

If Cityblock can spend less than $40k on average to treat its patient population during the year, it keeps the difference.

If it costs more than $40k on average to treat its patient population during the year, it’s on the hook for the losses.

The name of the game, financially, for Cityblock is to use the money it spends to decrease the money it pays out, and to keep the total of those two below the money it receives from insurers.

(Note: I am clearly leaving out a lot of nuance here. For example, in some cases, Cityblock splits some of the savings with insurers.)

Obviously, this would be a risky trade to make on a single patient. If that person ends up in the ER a couple of times, the economics are shot. Instead, Cityblock focuses on total populations and total outcomes. It works with plan partners like EmblemHealth to identify populations of people within the plan partners’ coverage group that Cityblock can help and negotiates the amount of payment per month per member with the plan partner to take over their coverage and care. Instead of being at risk $40k for each member, they might manage $400 million on a population of 1,000 members.

Cityblock uses data science to determine which segment of the plan partner’s population it’s most likely to be able to deliver results for (it spun out of Alphabet, after all). Patients with super high pharmaceutical spending, for example, are expensive, but there isn’t much Cityblock can do to help them, whereas patients with behavioral health issues, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension would benefit from a holistic approach. The goal then is to keep the total cost to serve that group below $400 million while improving quality outcomes, reducing ill-health and disability, and delivering a respectful and valuable experience. Cityblock needs to solve for all of those goals; it has quality, access, and experience guardrails in place to ensure that cost savings don’t occur at the expense of health outcomes.

What Cityblock has at that point is a list of people it can work with. Then, it needs to convince those people to become Cityblock members. The pitch: we’ll help you more, but you don’t owe any more.

Once members opt-in, Cityblock effectively becomes both insurer and care provider for thousands of people with the most complex situations. Its job is to find solutions that make those people healthier and keep them from needing to go to the ER.

I love this model. Instead of insuring someone and hoping for the best, or making the member choose from a limited menu of existing healthcare options that are covered by Medicaid, Cityblock puts itself on the hook. It takes the money upfront and full responsibility, then simplifies a ton of complexity, limits the traditional downsides to dealing with Medicaid, and greatly expands the tools at its disposal. If it thought the best way to make patients healthier was to buy them all NFTs, it could do that. (I don’t think that’s the answer, btw, I haven’t gone that far down the rabbit hole. Just saying.)

Ultimately, value-based care circumvents limitations in the system and gives Cityblock license to treat the whole person in the way they see fit.

The Product: Treating the Whole Person

Cityblock’s product is a combination of people, technology, and data that it uses to deliver care to handle all of the complexity it needs to in a way that’s ultimately scalable and repeatable.

Numbers are clean and simple. Get $40k, spend $35k, make $5k. Everything that goes on behind the scenes to deliver results for members is not.

Toyin remembers the day they signed up the first Cityblock member. It was, I kid you not, July 4th, 2018. If Cityblock fixes healthcare in America, it will seem like they went back and rewrote the story, so I’m just putting it down here for posterity.

Anyway, Cityblock had signed its first plan partner a couple of months after launching. The plan partner gave them a list of its 1,500 highest-risk members in central Brooklyn, the ones with all of the challenges, and left it up to the Cityblock team to find them, and convince them to opt-in.

On July 3rd, the team hit the streets to find them. For some, they only had a name or an address. They knocked on doors. On the second day, Independence Day, they saw their first member. He was an older gentleman, in his eighties, living in the basement of his family’s home in East New York. He was blind, didn’t have medications, was living in a “dark cave,” and hadn’t seen his healthcare provider for years. The team did a three hour comprehensive assessment, right there, in the basement. They told him they could help, and they asked him to opt-in to working with Cityblock. He did.

He was first, but he wasn’t unique.

The normal member is minding his or her own business when they get a knock on the door or a call on the phone. Someone from Cityblock explains that they’ve partnered with the member’s insurance to provide a bunch of additional services at no additional cost. That their job is to help them figure out how to achieve their goals.

But it’s not an easy sell. Remember, these individuals are often rightfully mistrustful of the system, and of healthcare institutions. They’re used to people chasing them down for exploitative payments. And mostly, so few of the things that the healthcare system has done have actually helped in a permanent way.

So Cityblock does everything they can to not feel like a healthcare institution. They hire “Community Health Partners” from within the communities they serve. They give them lots of latitude to get the job done. Community Health Partners build a direct relationship with members. They give them their cell phone numbers. Members don’t deal with “Cityblock,” they deal with “Joe,” a person from their community who’s on their side.

Once the member opts-in, the real work begins. Now that you’ve acquired some of the hardest-to-serve customers out there, what do you do?

In 2011, Atul Gawande wrote a piece for The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters.” The subtitle asked a question: Can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care?

In the piece, Gawande told the story of Dr. Jeffrey Brenner and The Camden Coalition. If you’re interested in value-based care and healthcare costs, you should read it. It set off a decade of investment and experimentation around the idea that we can lower healthcare costs by identifying hot spots -- areas where people with the highest healthcare costs lived -- and throwing the kitchen sink at helping the most at-risk, highest cost people. The Camden Coalition didn’t just treat symptoms, they tried to fix the root causes.

One patient, for example, wasn’t taking his blood-pressure pills. “His finger-stick blood sugar was twice the normal level.” The nurse practitioner assigned to this patient realized the problem was his living environment -- ant-infested, covered in trash, with fruit rotting on the table -- so she and the team found him a new place to live with support on-site to make sure he took his meds. Instead of liver failure and dialysis, which would have cost tens of thousands of dollars, he had a new living situation and more support. An ounce of prevention to save a pound of cure.

The Camden Coalition and other projects like it -- Romm and Ajayi met at the Commonwealth Care Alliance in Massachusetts -- proposed a new model, one that takes advantage of the second arbitrage: it’s cheaper, and more effective, to take care of people upstream than to deal with the consequences downstream.

As Bay put it, “There’s an extreme emergency medical safety net, and almost no social safety net.” The government is willing to spend almost anything to keep a person alive when they come into a hospital, but is much less willing to spend the money it takes to address the issues that lead to their hospitalization in the first place.

Cityblock makes the opposite trade. It believes that by spending some of the money it receives from insurers upfront, on improving peoples’ lives, it can decrease downstream costs by limiting the most expensive events, like ER visits and dialysis.

So how do they do it?

It seems like there’s a path that Cityblock is on:

Find and build trusted relationships with the folks they serve, delivering high-touch services that drive down total cost of care,

Then find the right balance between productivity and member experience and outcomes,

Then expand to new populations and different risk profiles,

Then scale everything up.

In Phase I, Cityblock is focused on doing everything it can to improve outcomes and lower total cost of care. To do that, it puts together cross-functional Care Teams each responsible for about 1,000 members. Care Teams include pharmacists, physicians, therapists, social workers, Community Health Partners, geriatricians, and more. They’re all employed by Cityblock. They all have equity in the company. They work together on Slack and in Cityblock’s own system, Commons.

These teams do all the normal things you’d expect from a care coordinator and healthcare provider. They schedule appointments, they facilitate payments and handle insurance paperwork. They staff heavily: for instance, a clinic serving 4,000 members might be staffed with 120 staff, while for comparison, a One Medical clinic of the same size would employ about 10% of that. That’s how much more complex Cityblock’s members’ needs are.

But they go further. Prior to COVID, 80% of Cityblock’s visits happen in members’ homes, because they’re more difficult to engage and it’s important to meet them where they are. The best way to make sure someone shows up to an appointment is to bring an appointment to them.

The Cityblock team knows all of its members’ doctors. When members need to see specialists, they show up to the appointments with them. They act as surrogates. They make sure their members are getting all the treatment they need, and not paying for treatments they don’t. When disaster does strike, and a member ends up in the ER, Cityblock’s network gives team members a real-time feed of admissions. Cityblock team members show up to handle care transitions; at times, they are the only relationship in the member’s life who shows up in the ER with them.

Cityblock goes beyond doctors appointments, too. They have full-stack behavioral health and social workers in-house. Cityblock’s team helps members get on food stamps, handle their mail, and reconnect with their pastor or next of kin. When members face legal issues, Cityblock is there in court alongside them.

When COVID struck last year, Cityblock moved quickly to continue to serve its members. The company is based in central Brooklyn, among the hardest-hit zip codes in the country. The team built an 80-person call center in under three months. With in-person appointments limited, it switched to 99% video consultations. First, Cityblock tried asking members to access telemedicine appointments from their devices, but they didn’t all have devices. So Cityblock sent them tablets, but they didn’t all have reliable internet. Ultimately, Cityblock hired paramedics, rented cars, and told members, “Call us. We will be at your door in 90 minutes.” And they were. Paramedics showed up to handle members’ needs on-site and connect them with doctors for telemedicine consultations.

Technology was crucial to Cityblock’s survival during the pandemic, but it also plays a much larger role in the company’s plans. It’s what separates the company from the other, more local, value-based care organizations that have struggled to scale. The team knows the model works, they’ve seen it work at sub-scale. They need tech to make it scale.

On the front-end, they’re meeting members where they communicate, which is typically via text or call. Some members use a beta version of a Cityblock app for telehealth consultations over video or text, but many still choose to text their Community Health Partner directly. That’s cool, too. The real magic happens on the back-end.

Running Cityblock is like running an on-demand service like Uber, but with full-time employees and fewer, more complex interactions. It reminded me a lot of running Breather’s operations, with nodes all over the city and employees handling a variety of tasks for members in real-time, but instead of meeting space, Cityblock delivers healthcare and social services on-demand. That requires a ton of coordination and quick, smart decisions, and that’s what Commons helps Cityblock do.

In a 2019 blog post, Cityblock’s product team wrote that Commons has been particularly impactful for care operations in the field in four areas:

Measurable member & care team communications. The Cityblock team can easily communicate with each other and with members. Members can text their Community Health Partner directly, and feel that 1-1 relationship, and on the back-end, Cityblock can make sure that even if that person is unavailable, the member gets timely attention.

Task-driven personalized care plans.Gawande would be proud. This is the Checklist Manifesto in the field, with a Member Action Plan customized to each member.

Multi-source, data-driven decision support. Commons acts as one central point for all of a member’s data, from prescription refills to insurance claims and even social and behavioral factors, which help update the Member Action Plans in real-time.

Real-time care transitions. As highlighted above, when a member is hospitalized, Cityblock knows immediately and can intervene to improve care.

Cityblock’s tech will be crucial in allowing the company to scale and benefit from economies of scale. The goal is better, cheaper, more immediate and responsive care with fewer employee hours per patient. As with any labor-heavy services business, it will need to intelligently triage and coordinate labor, and improve operating efficiency with scale.

All of this sounds incredibly expensive, and it’s certainly not cheap, but the preventative work that Cityblock is doing is still cheaper than the existing model of waiting until a series of very expensive events. Cityblock is reducing the total cost of care in its existing population.

The Early Results

It’s still early -- Cityblock has done a lot, but it’s still less than four years old -- but the results thus far are incredibly promising.

Cityblock is experiencing 3x year-over-year revenue growth and serves about 75,000 members, mostly in New York, and across Connecticut, Massachusetts, Washington, DC, and North Carolina. More states are coming next year.

But the most important thing is delivering health outcomes. Toyin shared this theory of change framework to describe how they’re doing against that goal:

Find and Engage. Once Cityblock finds its members and gets them to opt-in, it needs to keep them engaged, just like any tech company (or newsletter). Health plans typically have single-digit engagement after a year. Cityblock has 70% engagement at a year.

Intervene. The name of the game in this model is to avoid expensive hospitalizations. Data from its first cohort suggests that Cityblock members have 20% fewer hospitalizations. That’s huge from both a medical and financial perspective.

Brand and Experience. To keep people engaged and interacting with Cityblock over time, and to get them to vouch for Cityblock with other hard-to-reach and mistrustful target members, it needs to create a positive experience for its members. The results there are eye-popping. Cityblock’s NPS is consistently in the high-80s and low-90s. That’s absurd for any company -- Apple’s NPS is in the 70s -- particularly absurd for a healthcare company, and particularlyparticularly absurd when you consider most members’ starting feelings towards healthcare.

Just as importantly, and especially promising for Cityblock’s long-term ability to scale, it seems as if the move to more virtual care resulted in lower costs for the same outcomes. In May, the American Medical Association (AMA) put out a case study on Cityblock. They found that during COVID, when Cityblock was forced to move to more virtual care:

Cityblock was similarly effective in reducing ER and inpatient utilization (hospital and doctor’s visits) with the virtual model,

Kept in contact with 85% of all members every 90 days,

Improved NPS from 77 in January 2020 to 91 in January 2021,

No-show rates dropped from 50% to 5% (the power of showing up to members’ homes),

Per member per month cost of care was lower in the virtual model.

These are absolutely incredible results, demonstrating that this model can work. But if Cityblock is trying to build a new healthcare system and improve care for marginalized people nationwide, it still needs to tackle some major challenges.

Challenges

So about The Camden Coalition, the organization that set the spark for the hot-spotting and value-based care revolution… it may not have actually worked.

As Olivia Webb points out in her excellent piece, Cityblock Health and The Camden Coalition:

A randomized, controlled study of the Camden Coalition model published by the New England Journal of Medicine showed no significant decrease in readmissions between the group that received high-touch, coordinated care and the control group.

In a response to the piece, Alina Schnake-Mahl, MPH, ScD, a former Evaluation Scientist at Cityblock and Pooja Mehta, MD, Cityblock’s Women’s Health Lead, wrote about their takeaways, and the differences between Cityblock and Camden, which Webb summarized as:

Cityblock is its own health system of sorts. Cityblock has more physicians, providers, and health “hubs” than the Camden Coalition did; rather than referring out to a network of doctors in the community, Cityblock handles most of its patients’ care within a single system.

Structural changes take time. The Camden Coalition study took place on a short time frame with providers who were limited in their referrals.

There’s more leverage available in treating a broader “rising-risk” population, rather than simply focusing on superutilizers. This is the big one. The Camden Coalition study focused on the extreme outliers, people who were already on a cycle of regular hospitalizations. The Cityblock team writes—accurately I think—that the best interventions happen before a patient enters a cycle of recurrent hospitalizations.

This last one is the most important. The Camden Coalition study focused just on superutilizers -- the people who go to the hospital over and over -- but Cityblock serves both people who would be considered superutilizers and “rising risk” patients, the ones who show signs of potentially becoming superutilitizers but aren’t yet.

Cityblock’s outcomes thus far actually show promising improvements for the highest-cost, most complex members -- that makes sense, there’s a lot more room for improvement when the baseline is so high. The Camden Coalition results were surprising and potentially anomalous for this group. The real question is how Cityblock can prevent others, particularly rising risk members, from becoming superutilizers in the first place, and whether they can do so on a reasonable enough time frame to have a meaningful impact.

The even broader question is how wide of a spectrum Cityblock can serve well and cost-effectively.

On the high-complexity end, will it be able to stop the cycle that superutilizers are in and decrease their utilization?

On the low-complexity end, will it be able to drive down costs to serve lower-risk members? Even if it is able to provide better care for lower-risk, lower-complexity populations by leaning on technology to acquire, engage, and retain members more cheaply, and provide more scalable care through telemedicine, will it be able to convince insurers of its impact?

In other words, if Cityblock saves insurers money in a decade by treating lower-risk people today, before they start costing insurers a lot of money, will it be able to convince insurers to pay?

What about churn? What if Cityblock’s approach, helping members improve every aspect of their lives, is so successful that they’re able to earn enough money to no longer qualify for Medicaid? To be sure, that would be an incredible problem to have, but unit economics are important for any business, particularly a multi-billion dollar startup with public market ambitions.

Finally, as Cityblock transitions from Phase I -- proving that they can lower total cost of care by throwing everything at the problem in a handful of markets -- to building a nationwide business at scale, it will need to balance Care Team productivity with member experience and outcomes. How can Cityblock deliver the same results with a lower Care Team member per patient ratio as it grows? The value-based care model is about generating gross margins, but to build a sustainable business that will attract enough resources to revolutionize healthcare, the entire business will need to become profitable at some point.

These are all real challenges and real question marks, and I’m not an expert, I’m sure I’m missing a bunch more.

That said, what Cityblock has accomplished in just four years is spectacular. It no longer needs to answer the question “Will this work?” It’s answering “Just how big, impactful, and transformative can this become?”

The Future of Cityblock, and Healthcare

There are two broad categories of reasons that people might think what a startup is trying to do is crazy and impossible:

It actually is crazy and impossible, or

They just don’t see how it’s possible yet.

In either case, operating in a space that others think can’t work gives you a head start. In the former, that’s a head start to nowhere; in the latter, it’s an incredible and nearly insurmountable advantage.

It’s beginning to look a lot like it was the latter in Cityblock’s case. Now, the company has a four-year head start and a vertically integrated machine comprised of tech, ops, medical chops, experience, payer relationships, and hundreds of millions of dollars that will be nearly impossible to catch. If anyone is going to make Cityblock’s vision a reality, it’s Cityblock.

This was likely already true after Cityblock thrived through COVID and accelerated the development of its virtual care model. Tiger cemented it in March.

Cityblock didn’t need the $192 million. After General Catalyst’s investment in December, the team had a couple hundred million in the bank, 4-5 years of burn, and a plan to double the size of the tech team to 100 people and total markets to ten. Unlike startups like Uber or DoorDash or WeWork that could use venture capital to acquire customers with poor unit economics in a bid for all-out growth, the #1 thing Cityblock needs to prove is that its unit economics work, and improve at scale. It can’t just light the money on fire in pursuit of growth like other startups. There’s too much at stake.

But the money certainly makes it a lot harder for new companies to come in and compete, and likely makes Cityblock an even more attractive partner to states and plan partners. Cityblock is here to stay. And expand.

Cityblock will continue to bring new members on the platform, from the 75,000 members it has today to its goal of 10 million by 2030. To do that requires working all of the ways that it brings lives onto the platform: through health insurers, states, the federal government, patients themselves, and even through some provider systems.

It also means expanding who Cityblock can help, from the high and rising risk Medicaid and dual-coverage population today, to children, pregnant mothers, lower-risk populations, more behaviorally complex individuals tomorrow, and to people with risks of specific medical conditions, like heart problems, in the future.

It might be able to use its data and expertise serving high-risk members to build digital-only products for lower-risk members, maybe even commercially insured. I would love a personalized Member Action Plan for myself; it might get me to go to the doctor.

It will need to learn new skills, adding more traditional low-cost customer acquisition and engagement channels to the mix in order to be able to serve communities with potentially lower risk and lower margins.

In some cases, the model might work immediately, driving down total cost of care, improving lives, and earning a profit on the population level. In others, it will need to learn, adjust, and continue to refine the model.

In the future, Cityblock might go deeper into serving high-risk people with complex needs across Medicare and potentially the commercially insured. Treating the whole person should work in other populations beyond Medicaid recipients, which would open up massive new markets. Medicare is a $799 billion market, and the combined Medicaid and Medicare markets are growing fast.

It’ll run into competition there. Companies in the Medicare space have received more funding. Some have even gone public recently, led by Oak Street Health. Oak Street, like Cityblock, is a value based care provider, with a couple of key differences: it’s more focused on Medicare recipients, and less focused on tech. The company’s S-1 highlighted a management team without any tech leaders.

Oak Street went public in August at a $9.6 billion valuation, and its shares have risen 45% since. It currently trades a $14 billion market cap on projected FY21 top line revenue of $1.3 billion (that’s the number states and insurers pay it to manage patients). Its performance is more of a market validation of the value-based care model than a temptation for Cityblock, which says that it’s interested in a similar outcome someday, but that it’s very heads down for the years to come.

That’s what they all say, but there’s so much left to build and so much money in the bank that I believe them. There aren’t many (read: any) other categories out there that measure TAM in the double-digit percentages of GDP and have so much opportunity left. Healthcare is pretty much it, and it’s ripe for improvement.

Some of that improvement will come from point solutions that address one condition or another. Others will come from enabling tech solutions that make it easier for a new generation of entreprepreneurs to build in the space. There are incredibly exciting developments in biotech, and the COVID vaccines were a triumph for mRNA.

But to drive down ballooning and out-of-control healthcare costs, much of the improvement is going to come from Cityblock and other companies like it that are willing to take on risk to show that there’s a better model that starts further upstream, treats the person, and drives savings downstream.

If Cityblock succeeds in its mission, it will save and improve millions of lives, change the model of care in the country, and save taxpayers trillions of dollars that can be put to better use proactively growing the nation instead of reactively applying band-aids. It’s hard to think of any other companies with the potential to do as much good.

So if you’ve read this far and are feeling inspired, here’s the ask:

The system isn’t going to fix itself. Cityblock needs the best and brightest on its side to fix it. If you or someone you know wants to help fix healthcare and knock basis points off of the US government’s largest spending category at a well-funded company led by kind, brilliant leaders, Cityblock is hiring. Join them. It’s a career arbitrage, of sorts: do well by doing good.

Thanks to Bay Gross, Toyin Ajayi, Gil Kazimirov, and Bridget Halligan for working with me on this piece and teaching me about Cityblock, and to Nikhil for the input!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Thursday,

Packy

I really, really hope this works and can be scaled across the country, though it does sound too good to be true.

The US can easily get 2% GDP savings by doing healthcare better and smarter. Those gains could be invested in so much else or used to pay down debt.

[I can't believe I am the only commenter!]