Welcome to the 2,417 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since the last 2020 email! If you aren’t subscribed, join 29,252 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by…

Pipe is building an entirely new asset class based on recurring revenue contracts. It’s not equity and it’s not a loan. Pipe lets businesses raise money today by selling their monthly or quarterly subscription cash flows directly through its platform, without needing to raise more dilutive venture capital.

Since I wrote about Pipe in October, the company has been busy. Now, you can sign up and run through a self-serve walkthrough to see what it’s like trading your subscription revenue.

For any recurring revenue business, checking how much your recurring revenues are worth on Pipe is a no-brainer. Sign up and find out how much cash Pipe can send you today.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday! I hope you all had a great holiday, and that it’s not too rough getting back into the flow of things this morning.

Every year, on New Year’s Day, I take some time to reflect back on the previous year and set some goals for the year ahead. This time last year, I was in the middle of starting an in-person community business and writing this newsletter’s predecessor as a fun side thing. I set a goal to hit 1,000 subscribers by the end of 2020.

Here we are on the first Monday of 2021, and there are more than 29,000 of us here, and all of my professional focus and goals are centered on this thing.

One of the goals I wrote down is to keep improving the content, pushing myself, and trying new things. In that spirit, why not kick off the year with something I didn’t do at all last year: a bear case.

Let’s get to it.

Bill-A-Bear

It was the fifth email in a long back-and-forth with a sponsor that changed me, made me bearish on a company not named “Quibi” for once.

Here’s how it went down: a company sponsored Not Boring. They wanted to pay me, asked me to invoice them on bill.com. Wham, bam, thank you sir. But they kept trying to pay me and they kept getting notifications that it didn’t work. I kept trying to fix it on my end, even upgraded to a paid plan, kept telling them that it was fixed.

“Should work now!”

“Nope. Maybe you should contact customer support.”

“OK got it, all squared away. Try again!”

“It didn’t work.”

Finally, on the fifth try, we got it, but not before a strange and unusual feeling set in: I was officially bearish on bill.com.

It’s not in my nature to be bearish. When I set out to write a takedown of SoftBank, I came away kind of loving Masa. As I wrote last time, I’m a natural born optimist. I have a really hard time seeing the downside. But every time I have to log into bill.com, a little bear growls loudly on my right shoulder, drowning out the typically ever-present angel on my left.

Finally, the growling got loud enough that I decided to look at the numbers. Surely, if I felt this way, others did too. That must be reflected in the stock price, right? Wrong.

Bill’s stock price nearly quadrupled last year, and the numbers don’t support the move. Bill is a bottom-quartile BVP Emerging Cloud Index company trading like a top quartile one. Its revenue growth is slowing, its revenue multiple: dizzying, its free cash flow: negative. It faces competition from powerful incumbents, fintech darlings like Stripe and Square, and new startups like Settle. And did I mention its product? It feels like something a Salesforce Product Manager would dream up if Salesforce enacted Google-like 20% projects.

(Ed. note: I learned, after writing this sentence, that indeed, bill.com’s first two engineers came from Salesforce and the company bought the domain from Marc Benioff. If it walks like a Salesforce and quacks like a Salesforce, or something.)

Now look, I don’t want to pick on bill.com. The company’s 618 employees are trying their best, and they’ve built a company worth over $11 billion. I, as a reminder, write a free newsletter. It brings me no joy to pop the Bill bubble.

But having a bad experience with bill.com was lucky. It forced me to sharpen my bear claws heading into a year during which sharp bear claws will come in handy.

While 2020 was a year for unbridled tech optimism, I think 2021 is going to be a year for discerning tech optimism. There’s going to be a flight to quality within tech. Market leaders with strong growth, big margins, profitability, and best-in-class products will continue to earn strong multiples, but laggards with outdated products and relatively unattractive numbers will underperform, regardless of sub-sector or market cap.

This whole bear thing is new to me, so we’ll take it one step at a time:

What is bill.com? A just-the-facts look at Bill’s product, business model, and distribution.

The Bill Bear Case. Bill.com touts the highest revenue multiple in the entire BVP Cloud Index, and it has neither the numbers nor the product to back it up.

The Love-Hate Relationship with Work Software. People hate old, locked-in enterprise software, and love the new breed of product-first, consumerized B2B SaaS. Bill.com’s product fits with the old guard, but it hasn’t had as much time as them to dig moats.

Killing a Baby Dictator. Bill.com is still small enough for competitors to defeat before it’s too late.

As always, this is not investment advice. I’m definitely not suggesting that you short a tech momentum stock in this market. The Keynes quote that, “The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent” rings truer every day.

What is bill.com?

Bill.com is founder René Lacerte’s second bite at the apple.

In 1999, Lacerte, a fourth generation entrepreneur, left his job at Intuit to build PayCycle and replace manual payroll with software. It looked like this:

In 2004, five years into the journey and faced with slowing growth, PayCycle’s board removed Lacerte from the CEO role. (PayCycle later sold to Lacerte’s old employer, Intuit, for $170 million in 2009.) After being fired from the CEO role, Lacerte served as CFO for a year before leaving the company to work on his next thing.

Lacerte’s next thing, which he founded in 2006, was originally called “CashView.” When Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff heard about it, he called Lacerte and offered him, for the low low price of $200k, a domain that he happened to own: bill.com.

Bill.com’s mission was and is to “make it simple to connect and do business.” It attempts to do that through cloud-based Accounts Receivable (AR) and Accounts Payable (AP) software for SMBs.

If it sounds unsexy, that’s because it is, but it’s also important. In any business, particularly SMBs, cash is king. A company can improve its cash position without doing a dollar more in sales or cutting any costs by stretching out payables and pulling in receivables. There’s even a formula for it: the Cash Conversion Cycle formula.

Bill’s promise is that by giving customers better tools and data, companies will receive money more quickly and pay out more slowly, shortening the CCC and putting more money in the bank at any given time.

The prize for helping companies simplify AR and AP and improve the cash conversion cycle is large: there are 6 million small or medium businesses (SMBs), those with revenues under $100 million, in the United States, and 75-90% of those businesses still pay for things with checks. Over the next decade, most of that volume will move online.

The question is: how do you capture it?

In tech, there’s a never-ending battle between product (the actual software) and distribution (how a company sells to customers). Bill.com is a distribution play.

Lacerte ran essentially the same playbook at PayCycle and bill.com:

Replace a paper-based finance workflow with software.

Distribute through partnerships with accounting firms and others who own the relationships with SMB clients.

Try to create network effects and switching costs and hold on for dear life.

Because PayCycle and bill.com competed with physically writing out paychecks and invoices, they had a low product quality bar to jump over. So they built something functional and tried to get it in the hands of as many people as possible as quickly as possible in a race to create network effects.

The focus on distribution over product shows. Even bullish articles about the company, like a16z’s When Distribution Trumps Product, concede that “while the company’s UI leaves much to be desired, its core product—sending payments and getting paid—works efficiently.”

I have some thoughts on the UI, but we’ll get to that in a bit. For now, let’s stick to the facts: the product, distribution, and business model.

Product

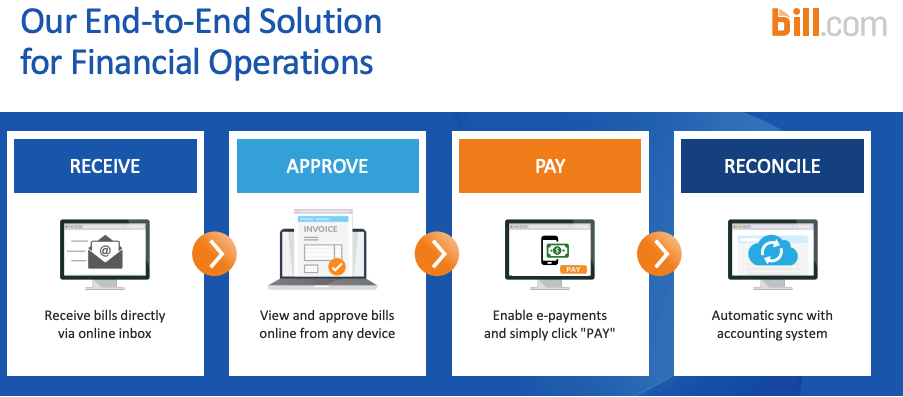

So what does bill.com do? Simply, it lets small businesses pay vendors, and lets vendors invoice small businesses and get paid. According to the company’s November 2020 Investor Presentation, it takes a process that looks like this:

...and transforms it into something clean and easy, like this:

The graphic shows the Accounts Payable perspective. Instead of the finance team receiving a paper invoice, emailing a business lead for approval, writing and mailing a physical check, and manually recording the transaction in the company’s accounting software, they just get a digital invoice, click approve, click pay, and they’re done. Simple!

My experience with the product is on the Accounts Receivable side. When a company sponsors Not Boring, I create an invoice on bill.com, write a message, hit send, and then sit back while I wait for the company to pay. Simple!

Theoretically, it’s all simple and easy. By connecting small businesses with their customers and vendors, bill.com wants to make it easy to pay and get paid, lower cash conversion cycles for its customers, and help SMBs thrive.

Distribution

Bill.com puts most of its eggs in the distribution basket. It’s the weapon with which it’s chosen to go to war against the status quo and new competitors. That distribution comes through four main channels:

In When Distribution Trumps Product, a16z’s Seema Amble writes about the five ways that bill.com fuels network-driven growth, which map to the four channels:

Minimize Friction (Direct to SMB). Bill.com’s online platform removed a ton of friction from the traditional paper and mail process.

Require Low Commitment, Deliver High Value (Direct to SMB). It’s free to start using bill.com, so it can prove value before charging subscription and transaction fees.

Compel Growth Through Design Choices (Direct to SMB). If a customer sends a vendor an invoice, the vendor needs to set up an account to pay online. Similarly, a vendor can invite a payee to create an account to receive payment. This should create virality.

Identify Adjacent Growth Channels (Accounting Firms & Accounting Software Providers) Bill.com sells into accounting firms (of which 4,000 use bill.com), who then get their clients to use bill.com. “More than 50 percent of Bill.com’s customers and 45 percent of revenue are derived from its accountant partners.”

Tackle Larger Distribution Nodes (Financial Institution Partners). Bill.com works with six of the ten largest US banks, who use bill.com to power better AR/AP solutions for their business banking clients. Partnerships like these are only possible with the scale of customers that bill.com built up via Direct to SMB and Accounting partnerships.

Today, 103k customers use bill.com to accept payments from a network of 2.5 million suppliers. This is Bill’s network effect: as more customers and suppliers use bill.com, the experience becomes better for every new company and supplier that joins, because they should be able to easily find and pay each other seamlessly.

Then there’s the switching costs: I’ve actually tried to stop using bill.com twice, and both times, I was brought back into the fold when a sponsor told me, “Sorry, we have to use bill.com here and it would be easier to pay you if you invoiced us there.”

Nothing like the threat of not getting paid to keep you from switching.

Business Model

Bill.com’s business model is straightforward. It makes money in three ways:

Subscription (53% of revenue). Monthly plans start as low as $39/mo/user.

Transactions (33% of revenue). Bill collects fees for every transaction completed through the platform.

Float (13% of revenue). Bill earns interest while payments are clearing. In my experience, that takes about a week each time.

The business model is strong on paper: it combines the predictability of monthly recurring revenue with the upside of transaction fees. It grows as it adds new customers, as its customers add more users, and as they make or accept more payments through the platform.

In the 12 months ended September 2020, it brought in $169 million in revenue, 86% of which came from subscription and transaction fees (float tanked as interest rates did). 86% of that core revenue came from existing customers, thanks to a strong 121% dollar-based net retention rate, a good sign that the company is able to lock in customers and grow with them. The network effects and switching costs seem to be working.

The numbers show a core business that’s solid if not spectacular. Analysts cite potential upside from new products like virtual card issuance, cross-border transactions, and instant transfer. The 121% dollar-based net retention rate is a good signal that the distribution → network effect lock-in strategy is working.

The market seems to like what it sees. Bill.com went public on December 12, 2019 at a $1.6 billion market cap on Q1 2020 revenues of $35.2 million and net losses of $5.7 million. A little over a year later, on Q1 2021 revenues of $46.2 million (31% higher) and net losses of $12.9 million (56% higher), BILL is trading at an $11.1 billion market cap (7x higher)!

Something’s off. I don’t think anyone on Wall Street has ever actually had to use bill.com…

The Bill Bear Case

On paper, bill.com’s strategy is elegant. Through smart distribution, it’s overcome a mediocre product and built a real network effect and switching costs. It worked in the 1990’s, why can’t it work now?

Well, in 2021, BILL is a bubble begging to be popped. As if to invite the dot com bubble comparison openly, it even has “.com” in its name. Who does that anymore?!

BILL is overvalued, and not just in the “oh lol 2020 got a little out of hand” sense. Bill.com is overvalued even relative to all of the other SaaS or fintech stocks that exploded in 2020, and unlike most of them, the product sucks, making its future much dimmer.

Ultimately, the bear case boils down to two things:

The Numbers. This one is so straightforward that I thought I was missing something. Compared to all of its comps, bill.com is too expensive. Normally, I’d squint my way past that and imagine a world in which it grows into the valuation, if it weren’t for…

The Product. Bill.com’s user experience is terrible. I know, I know, AR and AP are really hard. But at an $11 billion market cap in the year of our lord 2020, a good tech company’s job is to abstract away all of that complexity. Bill.com makes it clear that it’s hard. That makes me very skeptical that bill.com will be able to put up numbers that justify that valuation any time soon.

I’ll say upfront here that most analysts who cover the stock are bullish. According to SeekingAlpha, of thirteen sell-side ratings, seven are very bullish, two are bullish, and four are neutral. They get paid to do this for a living, and you should track down their reports for a balanced perspective.

I don’t buy it. Bill.com has already outrun their bullish average $125 targets and the multiples are too damn high!

The Numbers

Bill.com is wildly overvalued because it benefited from some uniquely 2020 tailwinds: namely, the surge in fintech broadly and investors’ ravenous hunger for lower-market cap tech companies.

In FY 2017, bill.com generated $64 million in revenue, growing to $108 million in FY 2018 and $157 million in FY 2019. That’s good (if slowing) growth, but it’s nothing compared to the stock price’s rise. Bill.com shot up 258% in 2020 (and that after a drop; it was up 297% when I started researching this piece).

With returns like that, I thought I must be missing something. The numbers must be great, despite my negative personal experience. So I checked the BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index to see how Bill.com’s metrics stacked up, sorted by EV/Annualized Revenue, and…

My god. At 56.4x, BILL is trading at the highest revenue multiple (LTM or Forward) of any of the 54 companies in the index. It also sports the seventh worst efficiency (21%), slightly below average revenue growth (31%), exactly average gross margins (74%), and the fifth worst LTM FCF Margins (-11%). Despite all of that, its YTD returns are the sixth best in the group.

(While we’re at it, I have a bone to pick with investors who dinged Slack for 49% YoY growth and bid up BILL at 31%.)

I felt like Kevin McCallister in Home Alone.

Even crazier, that outperformance came despite the fact that while COVID accelerated growth in many of the companies in the BVP Index, it hurt or fatally wounded many of bill.com’s SMB customers. As a result, bill.com’s revenue growth slowed while other fintech companies’ soared. Let’s compare it to Square, another fintech focused on SMBs, for example:

Both stocks performed about the same in 2020, with BILL coming out slightly ahead of SQ at 258.7% vs. 241.0%. Unlike BILL, SQ has the numbers to back it up.

Between Q3 2019 and Q3 2020, Square’s revenue grew an astounding 140%. Square’s revenue is weird, because when people buy Bitcoin on Cash App, it books the full amount as revenue, so to be charitable to bill.com, let’s look at gross profits.

Square grew gross profits 59% YoY to $794 million in Q3 2020, accelerating from 41% growth in the same period the previous year. Bill.com’s gross profit, meanwhile, grew 31% YoY, a sharp deceleration from the 62% growth it saw over the same period the year before.

Square was profitable last quarter, with $36.5 million in net income. Bill.com was twice as unprofitable as it was the same quarter the previous year, with $12.9 million in net losses.

Bill.com is growing more slowly than Square (and that growth is decelerating) off a much smaller base. Its product is worse. It doesn’t have the talent density or design focus that Square does. It serves a much smaller customer base, putting it at a distribution disadvantage. It doesn’t have a growth engine like Cash App waiting in the wings. It doesn’t have a $50 million Bitcoin investment that’s doubled since October. It’s losing money. And yet, while BILL’s EV/Annualized Revenue is 54.6x, Square’s EV / Annualized Gross Profit is 30.9x. That’s crazy.

Here’s what I think is happening, and believe me, I know this sounds stupid, but I think it’s also true: investors wanted to buy fintech stocks, saw that BILL only had a market cap of like $4 billion versus SQ at $50 billion earlier in the year, and figured that BILL had a lot more room to run. $1 trillion divided by $4 billion is 250, and $1 trillion divided by $50 billion is only 20, ipso facto, more upside. Or something like that.

To believe that bill.com has a shot at growing into its inflated valuation any time soon, you need to believe that it’s going to re-accelerate growth and that it’s going to keep growing for a long time.

I’m, uhhh, skeptical, because bill.com’s product doesn’t feel like a product built in or for this decade, and it’s going to face competitors whose products do.

The Product

Bill.com is the worst software I use to run Not Boring. It takes something that should be joyful -- getting paid! -- and makes it dreadful. That presents an opening for product-first competitors to cut off bill.com’s growth and pick off customers.

The idea for bill.com’s product sounds simple -- send and receive invoices and payments online -- and the product looks clean enough on the surface, but in my experience, there are a host of little things that add up to a poor product experience.

Poor Communication. When a sponsor pays me, there’s no communication or notification. The money just kind of floats in the ether. To find out where it is, I need to contact them through the “Message Center.”

Confusing UI. Often, a sponsor will pay me outside of bill.com, and the invoice sits there, marked as unpaid and overdue. It took me half an hour of clicking around to figure out how to mark the invoice “Paid.”

Issues with Multiple Bank Accounts. One of my bank accounts was approved, another wasn’t, or something, and when I tried to switch, without warning, I was no longer able to receive payments.

Poor Onboarding and Late Verification. Instead of verifying my identity upfront, I got a message in my Message Center asking me to upload my driver’s license and incorporation docs after I’d already completed a few transactions and was in the middle of another one, delaying payment. This could have been solved by a walkthrough at signup, a very normal feature in modern software.

Hard to Connect Directly with Vendor. Unless you have the right email address upfront when you create a vendor account, good luck figuring out how to connect to the right vendor.

There are more, but you get the point. To be clear, none of these issues is insurmountable, and if I worked in AP I’m sure I’d spend the time to get really good at bill.com, but in 2021, the counterintuitiveness of the product is striking.

Modern software, even B2B SaaS, is supposed to be intuitive. Magical little details that work better than expected are the norm. That’s the promise of the consumerization of enterprise SaaS: finally, work products that we love as much as the products we choose to use as consumers.

Today, a great product experience is table stakes. Or as Composer founder Ben Rollert put it so succinctly:

Product is just something that can’t be off, whereas distribution can be figured out. If there aren’t core product chops or an appreciation of it, a startup is basically fucked. So even if distribution is as important in the end, or even more important, it isn’t as much of a precondition.

While bill.com has chosen a distribution-first strategy typical of early B2B SaaS products, its competitors are building product-first, backed by strong distribution. For bill.com to ever have a shot at growing into its valuation, it will somehow need to fend off those competitors.

A couple of potential threats, namely Square and Stripe, are particularly dangerous for Bill.com because they’re product-first companies that have added powerful distribution to their arsenals. On a 2018 podcast I’ve quoted a couple of times, Patrick Collison told Tim Ferriss:

If they [startups] can create a product that is so much better than the status quo that they start to get organic traction, once you attach a real sales and marketing engine to that, it’s going to be really frickin hard for a big company to effectively compete because this organizational transformation to being good at software is just profoundly hard.

Neither Stripe nor Square focuses heavily on invoicing yet, and neither have built products with the full capabilities of bill.com’s, but both do offer invoicing products and bring an army of existing customers to bear, and can use their own distribution to come after bill.com.

Square had 350,000 active sellers using its Invoices product in Q1 2019, more than 3x bill.com’s, and has shown an ability and desire to offer a variety of products and integrations to help small businesses grow. If invoicing is really a market big enough to support an $11 billion company, I have no doubt Square will make a bigger push into Bill’s territory.

Stripe wants to build the economic infrastructure for the internet, and has millions of customers, all of whom could choose to use Stripe Billing for invoicing instead of bill.com to keep their finances in one place. Even a photographer we just worked with sent us a Stripe invoice. It was lovely and simple. Plus, via API, Stripe could give all of Shopify’s merchants white-labeled invoicing, all within their Shopify account.

And it’s not just the fintech sueprstars. On a recent episode of The Twenty Minute VC, host Harry Stebbings asked Avlok Kohli, the CEO of AngelList Ventures, what his favorite recent investment was. Without hesitating, he chose a bill.com competitor, Settle.

A lot of entrepreneurs will agree with Harry, and many will innovate on bill.com. It has an $11 billion market cap with a product that my friend Dror Poleg compared to “a government website from the 1990s” and of which one of Not Boring’s sponsors told me:

That is catnip to product-focused entrepreneurs. Stripe, Square, Settle, and a wave of new entrants are going to come after bill.com’s slice of the pie or adjacent ones, potentially threatening bill.com’s already-slowing growth prospects.

They’ll be the latest in a long line of entrepreneurs attracted by the Siren Call of building a better version of shitty incumbent B2B software.

The Love-Hate Relationship with Work Software

There’s a risk to the bill.com bear case: the market loves the companies behind the B2B products people hate using.

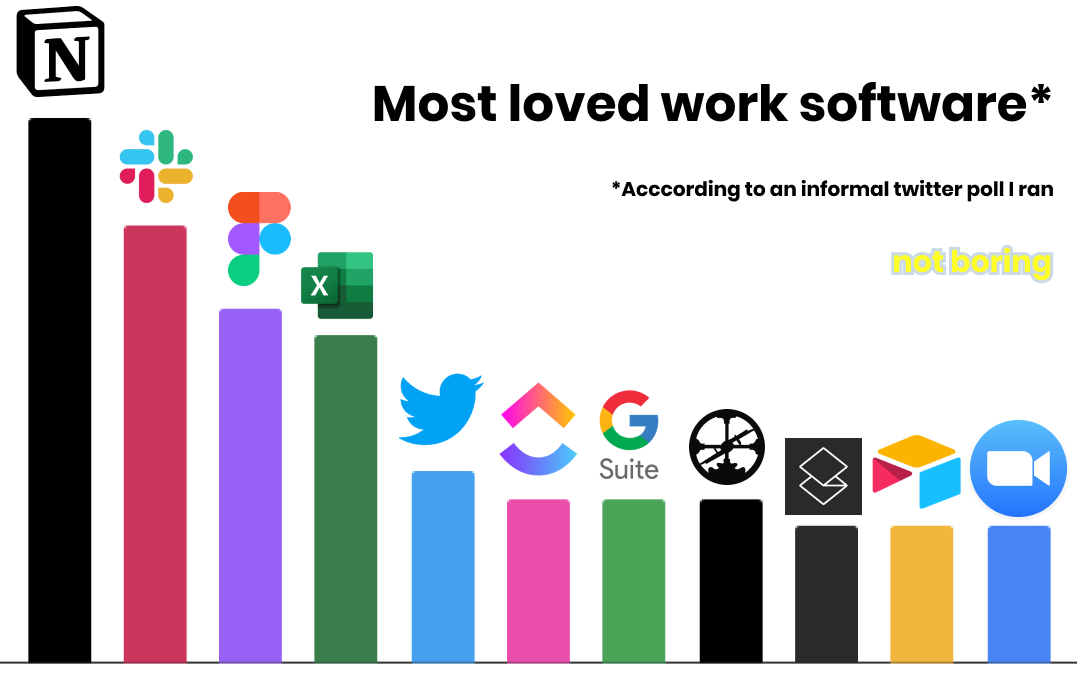

Last week, I asked Twitter for the worst software they have to use for work:

I got a lot of answers. People feel strongly about the shit they’re forced to use at work every day. Out of hundreds of answers, a few leaders emerged. Salesforce is the most-hated single product, but nothing holds a candle to Microsoft’s combined suite - Dynamics, 365, PowerPoint, Outlook, Windows 95, Teams, and myriad other gems got nearly 5x the votes of the next company. Powered by Jira and Confluence, that silver medal goes to Atlassian.

But here’s the thing. Over the past five years, the companies that make the most hated work software have performed really well…

The best performer and second-most-hated, Atlassian (TEAM) is up a whopping 753%. On average, the group is up 231.6%, compared with 82.6% for the S&P 500 and 157.4% for the Nasdaq. The only negative performer on the list, IBM, is only there because it bought Lotus Notes, and people still hate Lotus Notes.

If you bought an equally-weighted basket of the companies that make the software that business users hate the most five years ago (and added when newly public companies IPO’d), you would have outperformed the S&P by 4x and the Nasdaq by half! That’s a good hedge fund. How is that possible?

There are a few reasons.

First things first, to beat the naysayers to it, this data is incredibly messy and imprecise. My twitter universe is not a representative sample. Some of these companies are massive and also make products that people love. Microsoft users hate Windows, Teams, and Dynamics, but they love Excel. Slack is near the top of both the most-hated and most-loved lists. People love Google search and G Suite, even if some don’t like Hangouts.

Secondly, even being included on the list multiple times means that a lot of people use the product. Over a billion people use Microsoft Office; some are bound to hate it. On the flip side, I suspect that bill.com got just two votes because it only has 103k customers. It received no “most-loved” votes.

A bigger reason, though, is that most of the companies on this list are old. The average age of companies on the list is 34. They built moats during an era in which purchasing decisions were made centrally and the end-users, the employees, were just forced to use software that wasn’t very good. Back then, the B2B playbook worked:

Replace a manual process with software that was good enough but not great

Use large and expensive sales forces and partnerships to sell into IT departments

Build moats -- mainly network effects and switching costs -- to lock companies in.

The historical winners in B2B software famously and unabashedly focused on distribution over product.

Oracle famously sold vaporware to companies and governments knowing that the contracts and switching costs would lock customers in long enough that they would be able to actually build something. Listen to this Grubstaker’s podcast to get a sense for Larry Ellison’s priorities.

Microsoft’s big break came via a 1980 distribution deal with IBM, in which it included a clause that allowed it to retain the rights to sell its operating system to other companies. The company leaned on its distribution and bundling so heavily that it lost a 1998 antitrust case for pushing its own products through Windows at the expense of competitors and customers. It recently flexed its distribution muscle to push an inferior Teams product at the expense of Slack.

Salesforce is so locked in that companies buy other, more modern software to make it easier to interact with Salesforce. I’ve seen multiple pitches for companies promising to build better workflows on top of Salesforce recently.

SAP’s switching costs are so high that Hamilton Helmer used the company as the example for switching costs in his book on moats, 7 Powers. As Flo Crivello summarizes it, SAP’s switching costs mean, “Switching to another solution can be a months-long effort costing several millions of dollars, and much more in missed profits if done wrong.”

This is what SAP’s software looks like, for the uninitiated.

It takes some mighty powerful switching costs to keep people using something like that. Those companies have decades of moat-building to protect them against plucky startups.

Today, though, the product versus distribution debate presents a false dichotomy. A product has to be thoughtfully-designed, and increasingly, distribution is built into the product itself. I also asked Twitter for their favorite work software, and the winners are mainly from this new breed (Excel is a rare beast):

For the most part, they’re product-first companies with distribution baked into the product, and later turbocharged by strong sales teams.

Notion is designed for both private and public use. Every time someone exposes a portion of their Notion as a public-facing website, for example, the product spreads.

Slack built Slack Connect to help the product spread from company to company.

Figma’s whole product is designed with growth loops in mind. (If you haven’t, you should read Kevin Kwok’s Why Figma Wins now.)

While most of the companies on the list are still private and don’t report numbers, customer love seems to correspond to venture funding, which should be at least a rough proxy for company performance:

In April, both Notion and Figma hit $2 billion valuations.

Airtable raised $185 million at a $2.5 billion valuation in September.

ClickUp raised $100 million at a $1 billion valuation in December.

Roam raised a seed round at a $200 million valuation in September.

On the public side, Slack was the fastest SaaS company ever to hit $100 million in revenue, and recently sold to Salesforce (SAD!) for $27.7 billion.

We all know what happened to Zoom’s stock in 2020 (just in case: it rose 395%).

Product-first with built-in distribution is the new model. Customers love it. Investors love it.

A distribution-first company like bill.com would never even get off the ground in 2021. We’re past that. That brings us to the concluding question: is it locked in enough at this point that it’s going to stick around forever like Microsoft, Salesforce, and Oracle, or do competitors still have a chance to take it down?

Killing a Baby Dictator

There’s a question that ethicists like to pose over a couple of drinks: if you could go back in time and kill a dictator / terrorist / murderer when they were still a baby, would you do it?

We can’t go back and kill SAP, Salesforce, or Microsoft. The switching costs are too high, the moats are too deep, and companies are too locked in. Those companies’ customers will have to die out for their products to die out. But it’s not too late to stop bill.com.

I think what ultimately offends me so much about Bill’s product experience is that it’s the first time I’ve encountered a new work product that wasn’t well-designed in a long time.

I expect Salesforce to suck. It’s been around for a while, since before the software we use at work was supposed to be good, and it’s too late to do anything but build better interfaces on top. Salesforce got big enough, fast enough that we’re stuck with it.

But bill.com has a 2006-vintage product with slow enough growth that most potential customers are just finding out about it in 2020. It only has 103k customers in a market that it says is 6 million potential customers strong. For anyone, like me and the 5.9 million other target customers just discovering bill.com from today onward, the product experience is jarring. It’s like walking into a Mercedes dealership today and having the salesperson pass off an obviously used 2006 E-Class as the newest model.

Bill.com has left a wide opening for new entrants to come in and build better AR/AP software that makes getting paid fun and helps companies better manage their cash conversion cycles.

To knock off bill.com, Square, Stripe, Settle, or a new, product-first competitor will need to:

Build a seamless product to feature parity with bill.com on the things that matter to customers.

Build distribution into the product workflows.

Build up enough customer demand to attract enough vendors and partners onto the platform that Bill’s switching costs and network effects are rendered obsolete.

With those companies’ product cadence and 5.9 million customers ripe for the picking, many of whom have moved online during the pandemic, I like their odds. When they do, they’ll limit Bill’s upside and make it impossible for the company to grow into its impossibly high valuation.

Even after a wild run in 2020, I’m still incredibly bullish on tech companies. Product-first companies with built-in distribution will create the next generation of $100 billion+ market cap giants. Bet on those companies, even if their market caps are much higher than bill.com’s.

As for bill.com? I’m not shorting, because shorting anything in a market like this is asking to burn money, and there’s always the risk that one of the old guard sees a younger version of itself in bill.com’s product and buys it.

Instead, I’m considering selling long-dated OTM calls. Heads, bill.com tanks or stays flat, I win. Tails, bill.com rockets another 50%, and I lose some money, but I can only imagine how well the other companies in my portfolio would be doing. It’s a small hedge on my very overweight tech portfolio.

Plus, if the trade works out, it will be the easiest time I’ve ever had getting paid via bill.com…

Thanks to Dan and Puja for editing.

Important Note: This is not investment advice. I am not a registered investment adviser. Everything in this essay is for learning and laughs only. I do not have a position in BILL, but may consider putting one on.

On Thursday, I’ll be back to being unabashedly bullish with a Not Boring Investment Memo and a Not Boring Podcast first…

Thanks for reading,

Packy