Absolute Unit

The Banking-as-a-Service rocketship bringing banking to where people are

Welcome to the 545 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since Monday! Join 77,171 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring, the whole thing, is brought to you by… Unit

Unit is a banking-as-a-service platform that lets tech companies embed financial features into their products. Developers can sign up for Unit’s Sandbox to start building banking into your product in days, not months. In the background, the Unit team keeps making the product better; in just the past two days, they shipped white-labeled UI and an integration with Plaid Exchange. (If that’s your kind of shipping cadence, check out their jobs here).

If you’re a tech company with a loyal audience that wants to make your customers’ lives more convenient and create new revenue streams, you should sign up for Unit today.

Hi friends,

Happy Thursday! After a few weeks’ hiatus, we are back with another Sponsored Deep Dive x Investment Memo.

As a reminder (or an introduction for the Not Boring Newbies) I’ve always said that I only write Sponsored Deep Dives about companies I’d want to invest in — the whole point is to expose you to some of the most exciting and innovative startups out there before anyone else does — and now that Not Boring Capital exists, I put my money where my mouth is whenever possible. You can read about how I select Sponsored Deep Dive subjects here, and increasingly, I plan to write them about portfolio cos.

You might be able to sense a theme in these deep dives. Software has eaten the world; now, it’s finance’s turn. We’re programming money into everything. One of the manifestations of that is web3 -- crypto makes everything ownable. Another that I’ve been fascinated by is fintech, and particularly fintech infrastructure. Better infrastructure is redefining who can offer and access financial products and shifting the balance of power in favor of companies with audiences.

Let’s get to it.

Absolute Unit

Last year, I was discussing a consumer fintech company with Byrne Hobart, the author of The Diff, who’s way smarter than I am on fintech (and all subjects tbh). He made an observation that’s obvious in hindsight, but that was particularly succinctly-put and has stuck with me since:

For any fintech product the question always comes down to: do they have a sustainable advantage in low CAC? Robinhood does, but almost every automated wealth management company ends up with a CAC/LTV model that's super sensitive to long-term returns and user churn, so they have to pay a ton to compete with whoever has the most optimistic assumptions in that regard.

We were talking about a wealth management product, but the argument applies to fintech companies more generally. Here’s what he meant.

Businesses spend a certain amount of money to acquire each customer -- the Customer Acquisition Cost, or CAC -- and they hope to make many multiples of that money back over the time that the customer continues to use their product -- the Lifetime Value, or LTV. The lower the CAC and the higher the LTV, the better. Put starkly, spending $1 to acquire a customer who pays you $100 over time is better than spending $100 to acquire a customer who pays you $1 over time.

(This post by Ro CEO Zach Reitano and CFO Aron Susman, DTC Metrics Explained, goes in depth if you’re interested in learning more.)

Byrne’s point was that when everyone is going after the same customer via the same channels with similar products, the company that can convince itself that it can make more money per customer will pay more to acquire those customers. The most optimistic company gets the most customers, even if the optimism was misplaced. If they’re too optimistic, they lose money. The more accurate companies lose customers. Everyone loses.

In the beginning of a new industry, when there’s less infrastructure and less competition, the battleground is product: can you actually build the thing you say you’re building? Over time, as a space matures and the building blocks become standardized, the battleground moves to audience. When anyone can sell some version of the same thing, acquiring customers becomes the hardest part. That’s why Google and Facebook make so much money. As more competitors vie for the same customers, CAC goes up, and companies need to either accept a lower CAC/LTV ratio, or increase LTV by increasing prices, cross-selling more products, or improving retention.

This is true across industries, and it’s particularly true in consumer fintech. There are only so many financial products that most people buy -- bank accounts, debit cards, credit cards, loans, investing, transfers, wires, and a few other things here and there -- and the market is enormous. That means lots of companies offering similarish products and either competing for the same customers directly or going after ever-more-targeted niches. Starting from scratch today, it’s nearly impossible to profitably build a neobank. There are too many competitors converging on the same product suite targeting the same customers. The CACs are too damn high.

But what if you could go where the customers already are?

That’s the bull case for Unit, a banking-as-a-service (BaaS) platform that lets tech companies embed financial features into their products. It improves the CAC/LTV ratio from both sides of the equation:

Sustainable Advantage in Low CAC: Non-fintech tech companies (think Etsy, Uber, Mindbody, etc…) already have engaged, often large, audiences to whom they can provide financial products, instead of competing for new customers on the open market.

Generate More Revenue: Financial products give tech companies tools to increase retention and generate more revenue per customer. There are five revenue streams that companies can tap into by embedding financial features, and Unit built a handy tool companies can use to see the potential revenue impact of each.

Unit flips fintech economics on its head by teaming up with the companies that have already won the trust of their customers. No additional CAC, more LTV. In some cases, Unit can even reduce its clients’ CACs, like it did for Wethos:

That’s how you build profitable financial products.

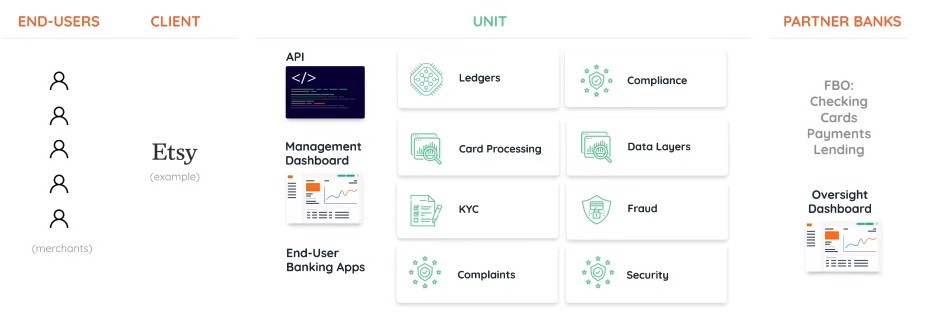

Unit offers a single platform of APIs, Dashboards, SDKs, white-labeled UIs, plus third-party integrations with best-in-class financial products, built on top of partner banks. It abstracts away all of the complexity; the client just deals with Unit, a one-stop shop for tech, compliance, and security.

By making it easy for a wider range of companies to offer financial products to their customers, Unit doesn’t really steal share; it expands the pie. Customers win. Tech companies win. Unit Wins. Even Unit’s partner banks win. Google, Facebook, and big banks lose.

That’s resonating with customers and investors. In June, Unit announced a $51 million Series B, led by Accel. I’m pumped that Not Boring Capital got a chance to participate in the round.

Unit is spreading like wildfire. Since I last spoke to Itai one week ago, Unit has grown its client roster by 17%. Today, I’ll explain why I’m so excited about Unit by covering:

The Fintech Apps-Infrastructure Cycle

Meet Unit

Standing out in the Competitive BaaS Space

Unit’s Growth and Opportunity

To understand Unit’s opportunity today, we need to look back at fintech’s recent history.

The Fintech Apps-Infrastructure Cycle

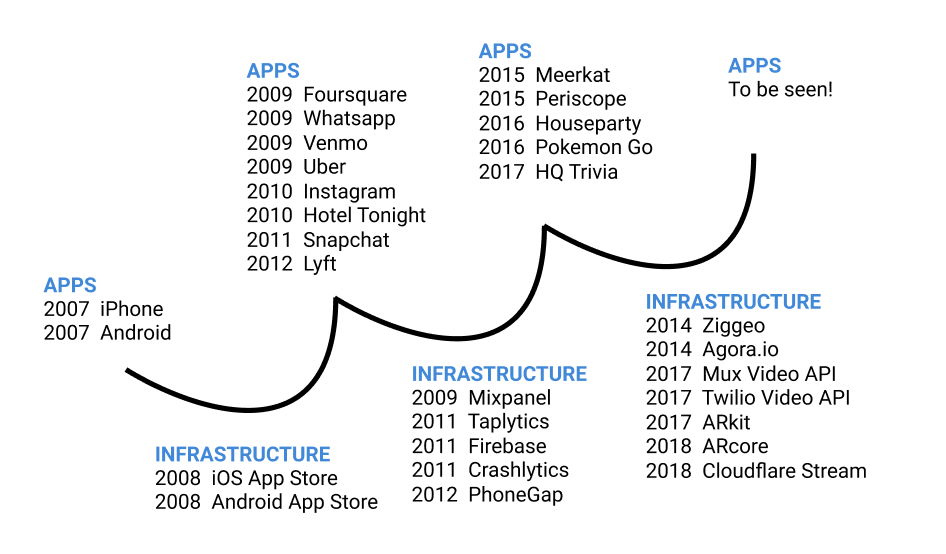

Last week, in The Interface Phase, we talked about the apps-infrastructure cycle, a framework proposed by USV’s Dani Grant and Nick Grossman to explain how apps necessitate new infrastructure, and infrastructure enables new apps.

Fintech has been in its own apps-insfrastructure cycle since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Fintech wasn’t really a thing before the GFC. There were companies that made it easier to do financial things online, like PayPal, but the industry didn’t really exist. Listen to any podcast with a fintech investor and they’re bound to say something like, “Look, I was just interested in how technology could [payments, lending, wealth management]. When I started, ‘fintech’ wasn’t a category like it is today.” Banks were dominant; tech companies were just hanging around the edges.

The 2008 Financial Crisis created a chink in the banks’ armor, and entrepreneurs took advantage by building a wave of end-user-facing financial apps -- neobanks, trading apps, roboadvisors, lending platforms, and the like. While it’s not a perfect proxy, the number of fintech companies in each Y Combinator batch rose dramatically from one in 2005 to 24 in 2016. Spot the leap: coming out of the GFC, fintech companies spiked from one in 2008 and 2009 to six in 2010, and never looked back.

Some huge apps were built during this era, which Unit co-founder Itai Damti calls Fintech 1.0: Robinhood, Venmo, SoFi, and Chime are four representative winners.

Early Fintech 1.0 apps had to do a ton of hard work themselves to get their businesses off the ground -- compliance, underwriting, clearing, connecting to banks, moving money, and much, much more. A new group of entrepreneurs saw the number of new apps, noticed that all of the Fintech 1.0 companies were doing the same hard things over and over, and set out to build infrastructure.

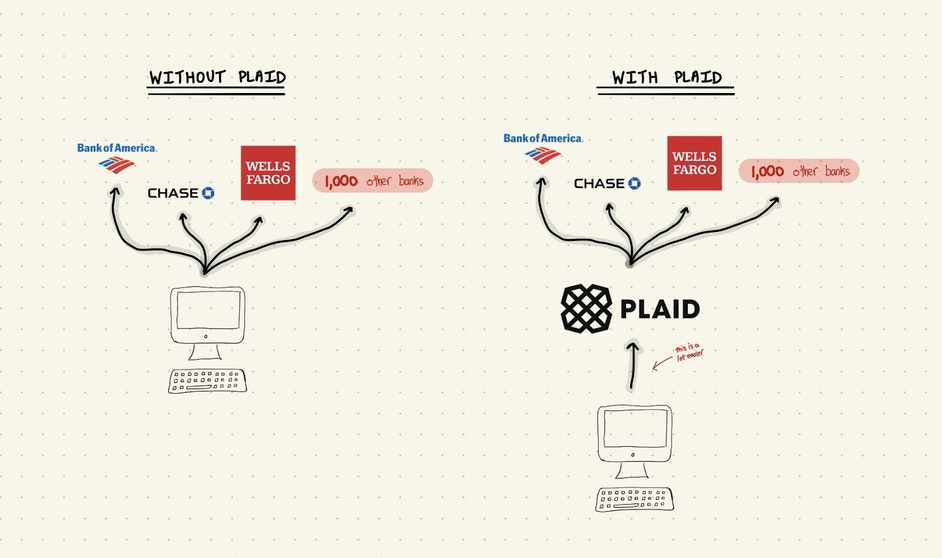

Plaid, launched in 2013, is an API-first company that lets developers connect their apps to peoples’ bank accounts. It sounds simple, but before Plaid, integrating with banks and then maintaining those integrations was a massive pain and resource drain.

Plaid started out working with existing players who felt the pain -- Venmo represented 40% of Plaid’s revenue in the early days -- but Plaid’s existence also expanded the market. By taking on the responsibility of one of the biggest headaches, Plaid made it easier for new entrepreneurs to build fintech products.

Plaid was the beginning of fintech’s first infrastructure phase, and today, there’s a whole host of infrastructure players that form what Alloy’s Charley Ma (also an investor in Unit) captured in “the 2020 fintech stack”:

a16z’s Sumeet Singh replied to Charley’s tweet with a table capturing many of the fintech infrastructure leaders in one clean table:

New apps highlighted the need for new infrastructure, and new infrastructure begot more apps.

Today, there’s a challenger bank, or neobank, serving every demographic you can think of, in the US and around the world. This 2018 market map from CB Insights highlights sixty of them that were around then.

Today, there are more. Neobanks.app lists 57 in the United States alone. Ads for Current are plastered to the construction site across the street from my apartment.

All of which brings us back to CAC. Last August, in Shopify and the Hard Thing About Easy Things, I wrote:

Here’s the hard thing about easy things: if everyone can do something, there’s no advantage to doing it, but you still have to do it anyway just to keep up.

When building product is easier, the competition moves to customer acquisition. That was the core insight behind Unit: Fintech 1.0 was about products; Fintech 2.0 is about audiences.

This is what happens, like a law of nature. On a long enough time horizon, all tech products will revolve around audiences. Vertical tech companies will bundle everything a particular audience needs in one place, including banking… until something else comes along and unbundles it all again. As Jim Barksdale said, “There’s only two ways I know of to make money: bundling and unbundling.”

Vertical tech companies have already spent tons of money acquiring those customers, and years of work building product and trust. They know more about their customers or workers than anyone else. They want to leverage that effort and understanding to provide more of what they need in one place. They want to offer financial services, but they certainly don’t want to think about becoming a financial service provider. Meet Unit.

Meet Unit

I knew I liked Unit when I first met Itai Damti, the company’s co-founder and CEO, but I didn’t know we were soulmates until I learned that before writing a single line of code, they first floated the idea for the company with a blog post. My kind of people.

Before Unit, co-founders Itai Damti and Doron Somech spent a decade building Leverate, a trading infrastructure company they co-founded in Israel. After Leverate, they knew they wanted to work together again, but they weren’t quite sure what they wanted to build. Sheel Mohnot, a fintech seed investor who runs Better Tomorrow Ventures (BTV) with NerdWallet co-founder Jake Gibson, told me:

Itai and Doron were thinking about different ideas for businesses they wanted to start. I wanted to work with them so much that I flew out to Israel to spend a couple of days brainstorming with them to convince them to build a fintech company so BTV could be involved.

BTV didn’t actually exist when Sheel flew to Israel, but Itai and Doron decided to build a fintech product, and Sheel committed to co-leading whatever they started. Then he started to fundraise for BTV so that they could invest in the deal. Itai had been an EIR at their previous fund, and they were eager to partner with him. “We knew we would back Itai in anything.”

So back to that blog post. On July 14th, 2019, Itai and Doron dropped Request for Bankers on Medium. They wrote:

After a few months of ideation at the intersection of fintech and dev tools, we believe we have landed on a complex problem we’d like to work on: building a US bank that helps technology companies launch rich, branded banking experiences.

Their thesis was clear from day zero. Banking was changing, new winners would emerge, and while they didn’t know who the winners would be, they “placed their bets on established tech firms.”

It’s common to distill all consumer fintech to the trillion dollar question “will startups get distribution before incumbents get innovation?”. Tech firms are positioned to win because they have the best of both worlds: the distribution and data of an incumbent + a startup’s obsession with product, user experience and growth.

Itai and Doron realized that tech companies have a “sustainable advantage in low CAC” for financial products, but that tech companies didn’t want to, and couldn’t, run and own an actual bank, for two reasons:

It’s expensive and complex. It took Simple (acquired by BBVA) 2.5 years and about $10 million to launch a bank, as their full-time focus! And that was just to get it off the ground; actually running a bank is also incredibly complex and painful.

Limits imposed by the US Bank Holding Company Act. The 1956 act “generally prohibited a bank holding company from engaging in most non-banking activities or acquiring voting securities of certain companies that are not banks.”

At the time of the blog post in July, Itai and Doron wanted to build a tech-first bank. Like, an actual bank bank. By the time they went out to raise their Seed round a few months later, in late 2019, the cover slide called what they were building, “Fintech as a Feature.”

Instead of a bank, they decided to build a platform. They realized that the access layer is the important piece, not the underlying financial institution. Point in case: Stripe is built on Wells Fargo. When’s the last time you heard anyone mention Wells Fargo’s contribution to the growth of online payments?

This diagram from the 2019 deck, which they used to raise a $3.6 million seed from BTV and TLV Partners, looks a lot like how Unit works today. As a platform, Unit sits in between the clients and partner banks.

Clients bring the audience, data, and products.

Partner Banks bring the bank licenses, checking accounts, cards, payment, and lending.

Unit brings a clean bundle of tech, compliance, models, and support, delivered to the client via a suite of APIs and dashboards.

With Unit, clients can launch a wide range of banking services in as little as four weeks for as little as $50k instead of 18 months and $2 million. Companies like Benepass, Invoice2go, MOS, and Lance can offer their customers any of the following products…

Checking accounts

ACH

Debit cards (physical or virtual)

Lending and cash advance

Wires

International payments

Checks

Bill pay

Credit cards

Fee-free ATM access

Tax calculation

… by integrating a few lines of code.

All of the individual components that go into banking are totally standard. Accounts, cards, and payments have been around for a long time, and there’s a finite list of ways to move money. Itai and Doron built Unit based on the belief that software is where banking can differentiate, by putting the building blocks in context, instead of in a separate banking app.

Unit packages up the building blocks, handles compliance, and gives clients APIs, SDKs, and dashboards. It’s up to Unit’s clients to figure out what they want to build for their customers with those primitives, how to put them in the right context.

As an example, Lance, a bank for freelancers, offers four accounts, each with a unique meaning to its customers. Lance’s software distributes any income between them automatically. The IRS bills one of them, the tax account, at the end of each quarter. As a sole proprietor myself, I can’t tell you how much existential dread I experience not having my taxes automatically deducted from a paycheck, like I would as a W-2. That bill is just hanging over my head. Lance knows its audience; I’d consider switching to Lance for that feature alone.

“Every company makes sense of finances for its own audience,” Itai said, “using the same building blocks.” With Unit, companies like Lance could get all of that built in as little as five weeks. And Unit just made it even faster.

With the recently launched Unit Go product, developers can spin up bank accounts and issue physical and virtual cards in five minutes instead of five weeks, so that they can test quickly and cheaply before going all in on offering banking products. That’s never been done before in fintech. It’s finance at software speed.

Of course, Unit isn’t the only Banking-as-a-Service player. It’s not the only embedded finance company. But it’s faster and easier, thanks to a strategic decision that sets Unit apart: it bundles everything together, including compliance.

Standing Out in the Competitive BaaS Space

Banking-as-a-service is a competitive space. Sheel from BTV broke it down into three buckets:

Banks with Fintech Programs. Some banks will work directly with fintech and other companies who want to build on top of them. Thanks to the Durbin Amendment to Dodd-Frank, banks with under $10 billion in deposits can charge higher interchange, which makes large banks uncompetitive here.

BaaS Providers That Sell Tech Solutions To Banks. These middleware companies, like Treasury Prime and Synctera, partner with both banks and fintech companies to make it easier for the two sides to partner.

Turnkey BaaS Providers. This is where Unit plays, alongside well-funded competitors like Bond and Rize. These companies make it faster to launch and easier to scale.

Unit will not be the only winner. While banks with fintech programs are losing ground to new, tech-first entrants, the other two categories provide stiff competition. BaaS providers that sell tech solutions to banks theoretically give more control to fintechs, because they can choose who to work with. Other BaaS providers offer different value propositions. Moov, for example, can be layered on top of any bank and maintains a commitment to its open source roots, but is mainly focused on payouts.

Unit offers one, packaged solution. For some companies, that won’t work. “If you’re building the next Chime,” Itai readily admitted, “you might want to use a less bundled approach.” Unit’s bet is that most tech companies will be happy to take the bundle, and that in the year of our lord 2021, no one wants to build (or fund) the next Chime. That era is over, its winners locked in.

Since BaaS isn’t a winner-take-all market, the key is figuring out which customers to serve and how to best serve them in order to win the most market share. The fun part about writing about strategy for a living is that there’s rarely one right strategy, but there is a way to do good strategy.

Richard Rumelt lays that way out in my favorite practical strategy handbook: Good Strategy, Bad Strategy.

In it, he writes that good strategy starts from the three-part strategy kernel:

Diagnosis. Identify the one or two key issues in a situation.

Guiding Policy. “outlines an overall approach for overcoming the obstacles highlighted by the diagnosis and tackles the obstacles identified in the diagnosis by creating or drawing upon sources of advantage.”

Coherent Actions. The set of interconnected things that a company does to carry out the guiding policy, each reinforcing the other to build a chain-link system that is nearly impossible to replicate.

In Unit’s case, everything stems from the diagnosis that tech companies with built-in audiences are best positioned to deliver embedded financial services and vertical banks to their customers.

The guiding policy based on that diagnosis might be to make it as fast and easy as possible for tech companies to build financial products into their main offering. There’s a trade-off here: fast and easy means clients can’t pick and choose every aspect of the banking stack. Unit’s software is flexible and programmable -- it built its own banking ledger from the ground up to let clients respond to transactions in real-time, take actions programmatically, and set flexible terms for different users -- but clients can’t bring their own sponsor bank or choose which card manufacturer to work with. Unit believes that most tech companies will care a lot more about convenience, speed, and programmability than which sponsor bank they build on.

Based on that guiding policy and diagnosis, Unit’s coherent actions link together to create a smooth experience and dig moats where they matter. Since most tech companies are not fintechs and not used to dealing with all of the specific complexities being a fintech entails, smooth means bundling everything together, doing the heavy lifting, handling compliance, and delivering everything via clean APIs and dashboards and banking apps.

Those actions work together. At the heart of Unit’s differentiation is the fact that it owns compliance for its clients.

Before Unit, companies that wanted to offer financial products had to find and cement the banking relationship, write software, and then write, maintain, and enforce 15-20 compliance policies on everything from privacy to infosec to KYC and KYB to AML to complaint management. Unit handles all of that, and condenses clients’ responsibilities to the things that they actually control, like the language on their website. (You can’t write that you offer 50% APY when you in fact offer 1% APY, for example.)

Unit can handle everything from beginning to end, starting with its white-labeled UI for applications. These are optional, because most companies do care about controlling every aspect of their user-facing experience.

Using Unit’s pre-made applications does three things:

Reduces friction and increases conversion by optimizing based on experience across dozens of clients.

Ensures that applications are compliant.

Collects the right information to fight fraud.

“We’re becoming a fraud powerhouse,” Itai told me. “All exploitable financial products, including bank accounts, get attacked by the same few hundred thousand fraudsters. We know how they work and what to look for.” Fraud patterns constantly change and evolve. In 2020, it was unemployment check fraud. This week, it’s something different. With dedicated teams, Unit can stay on top of the changes in the market on behalf of its entire customer base.

That’s just one example among many small decisions that add up to a coherent strategy and a smooth user experience. All in, handling compliance just makes life so much easier. To that end, Charley Ma told me:

Building on top of a BaaS provider is often marketed as being - hey here are all the APIs you need to open bank accounts, issue cards, etc it's super easy! But what's often underemphasized is that at some point, you get hit with the - “also here's a bunch of documents you need to figure out as to what are the compliance and regulatory requirements given down from your sponsor bank that you now also need to meet.”

We like to think that embedding fintech is as simple as integrating with "just a few lines of code," but the moment you're moving money on behalf of a customer in and out of bank accounts, the game changes.

Tech companies have other things to worry about. They want to make money. They don’t want to do compliance. So Unit abstracts all of that away.

Last summer, Unit hired Amanda Swoverland, a former bank regulator and Sunrise Bank’s Chief Risk Officer, to build out a compliance juggernaut. Today, compliance is the largest team at the company. Because compliance is so core to what Unit does, because it has so much data, and because it can spread compliance costs across a growing number of customers, it can hire the best people in compliance, build out their tooling, and stay on top of any developments. Because of its bundled approach, it can ensure that its customers are compliant when anything changes. That’s exactly what an API-first company is supposed to do.

In APIs All the Way Down, I wrote that:

The magic of companies like Stripe and Twilio is that in addition to elegant software, they do the schlep work in the real world that other people don’t want to do. Stripe does software plus compliance, regulatory, risk, and bank partnerships. Twilio does software plus carrier and telco deals across the world, deliverability optimization, and unification of all customer communication touchpoints.

Unit does software plus compliance, its own ledger, bank partnerships, and fraud detection. Giving software companies software and asking them to handle compliance is backwards. They can do software; often, they have no idea where to even start on compliance. By bundling it all together, they make it easy for the types of customers they want to serve to launch and scale.

That’s not the right approach for every customer. In Lithic’s new customer, I wrote that they were taking a different tack:

For the right type of customer, flexibility is one of the areas in which Lithic shines most brightly. The team at Lithic has built the product to pair well with best-of-breed infrastructure providers elsewhere in the fintech ecosystem: Alloy for identity verification, Plaid for open banking data and auth., Sila for money storage and ledgering, Wyre for fiat to crypto on/ off-ramps.

Many fintech companies take the best-of-breed approach in order to control which partners they get to work with. Unit might not be right for them (although Sheel points to the Braintree (modular) vs. Stripe (bundled) fight as evidence that companies ultimately choose convenience). But the thing about a good strategy is that it’s not about serving everyone; it’s about making the best choices to serve the type of customer you want to serve.

Unit’s strategy is centered around the belief that software companies will eat fintech. Its implicit bet is that every company is becoming a fintech company, the ones with loyal audiences and great software will win, and that those companies care more about convenience and a fast, clean experience than they do about controlling every aspect. History is on their side.

Just as Plaid made it easy to connect to users banks and expanded the market for fintech products, and just as Stripe made it easy to accept payments online and increased the GDP of the internet, Unit wants to make it easy to build financial products into any software product and pull forward a world in which “every company will be a fintech company.”

Unit’s Growth and Opportunity

It’s early. Unit launched less than a year ago. But the company’s early trajectory suggests that they’ve made a smart bet.

In December 2020, Unit launched and announced an $18.6 million Series A, led by Aleph, with participation from BTV, TLV, Operator Partners, and 30 angels, including Charley. TechCrunch included a chart that made Unit’s value prop clear:

Since launching, Unit’s approach has resonated with customers. Already, it’s signed over 70 clients (ten since last week). It’s grown revenue from $0 at the beginning of the year to multiple millions in under year. It’s created 40k new cards on behalf of clients in the past month alone.

Remember, the company has been live for ten months.

That kind of growth attracts investors, like me. In June, less than two years after its initial blog post, Unit raised a $51 million Series B led by Accel. Not Boring Capital participated.

More important than early growth or funding, though, is the fact that Unit’s thesis is playing out. Its customers are either pure-play software companies or fintechs from other categories (like wealth management or benefits) who want to expand into banking. Itai told TechCrunch that only 20% of its clients are true fintechs, whereas 80% are software companies that want to embed BaaS into their product. Unit is acquiring clients, like Wethos, Invoice2Go, Benepass, and Lance, who have already acquired large groups of specific customers.

And its clients are about to get a whole lot bigger. Major deals have not been announced, and I can’t break them, but Unit has signed major companies you’ve heard of and have likely used, and that I’ve written about, across investing, real estate, events, and medical. It’s even supporting a major Instagram influencer in launching a new kind of bank 👀

Unit has grown by focusing on what it does best -- tech, compliance, security, partnering with companies like Plaid and Alloy where useful, and letting its customers bring all of their benefits to the table: distribution, data, software, and trust.

There is a lot left to prove. Embedded finance is still a fraction of fintech, and fintech is a fraction of the overall financial markets. Many software companies might choose to turn to crypto instead of, or in addition to, traditional banking products, limiting the opportunity size. The space is incredibly competitive. Unit’s strategy is sound, but it needs to play out in practice.

Personally, I invested in Unit for a few core reasons:

We are still in the very early stages of the financialization of everything.

I believe strongly in the thesis that, across industries, going audience-first is the right strategy.

I believe that most companies, particularly most non-fintechs, want speed and convenience from their BaaS partner; API-first is about doing what you do best, and letting other people focus on the rest.

This is a massive opportunity, and Itai, Doron, Amanda and the Unit team are the right group to pull it off.

It’s impossible to grok how big the opportunity for embedded finance is today, just like it was impossible to predict the magnitude of the impact of software eating the world a decade ago. Already, tech companies are building roadmaps of financial features, just like they have roadmaps for their core software. Finance is becoming part of the stack.

Fintech is eating the world; Unit is bringing silverware.

If you’re a tech company with an engaged audience, you should check out Unit:

Stytch x Not Boring: The 0 to 1 Journey TODAY

As a reminder, I’m co-hosting a fireside with Thrive’s Gaurav Ahuja and Stytch founders Reed McGinley-Stempel and Julianna Lamb today at noon ET. Join us!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday,

Packy

So does the financialization of everything mean that I’m going to have as many financial accounts as I have media/streaming services? Not looking forward to that.

As a Canadian who values staying ahead in technology, I took pride in my savvy investments, especially in Bitcoin. Over the years, I managed to accumulate a significant amount, $400,000 stored in a wallet that I believed was secure. However, my confidence was shattered one day when a routine security update locked me out of my wallet. I tried everything I could think of to regain access, but nothing worked. To make matters worse, my wallet provider was of no help; they informed me that they couldn’t reverse the update and left me feeling completely helpless.

Desperate and anxious, I began searching online for solutions. That’s when I came across Cyber Constable Intelligence. Their glowing reviews from others who had experienced similar issues immediately caught my attention. I felt a flicker of hope and decided to reach out to them.

From my first interaction, it was clear that Cyber Constable Intelligence was different. Their team was prompt, professional, and genuinely interested in helping me regain access to my funds. They patiently listened to my predicament and assured me that they had successfully handled cases like mine before. Their confidence gave me the courage to trust them with my situation.

Within just a few days, I received the incredible news I had been longing for: they had found a way to bypass the security update and restore full access to my wallet! The relief I felt was overwhelming, like a weight lifted off my shoulders. I had nearly lost hope, but their expertise turned my situation around in ways I never thought possible.

Cyber Constable Intelligence proved to be a lifeline when I needed it most. Their dedication and commitment to customer satisfaction are truly remarkable. If you ever find yourself locked out of your wallet—regardless of how it happened—I wholeheartedly recommend Cyber Constable Intelligence. They possess the skills and knowledge to get you back in control of your funds.

Thanks to them, I can now breathe easily again, knowing that my investments are safe and secure. In the world of cryptocurrency, it’s reassuring to know that there are professionals like Cyber Constable Intelligence who can help when technology goes awry. Trust them to restore your peace of mind.

Contact info:

Website info https: cyber constable intelligence. com,

Whatsapp: 1 ( 2 5 2 ) 3 7 8 ( 7 6 1 1 )