Hi Friends 👋🏻,

Happy Monday!

This week’s essay is about oil, Zoom, podcasts, and glut. I could explain what’s going on with some supply and demand curves, but that would be boring. Instead, I turned to my old friends Hey Arnold and Positional Scarcity. It’s a walk down memory lane and a strategy for the present and future.

One quick thing: welcome to the 87 of you who have joined us since last Monday’s e-mail! If you’re here but you haven’t subscribed, it’s fun and easy. Just enter your e-mail and join us.

Now let’s get to it.

Wackos and ZoomGlüts

No one gives Hey Arnold enough credit for explaining economics. But “The High Life,” Season 2, Episode 10, of the 90’s Nickelodeon cartoon about a football-headed middle schooler, describes what’s going on right now with oil, Zoom events, and Clubhouse.

It’s about supply gluts and scarcity, and it is surprisingly instructive for creators figuring out how to deal with the current environment.

But first, let’s look at the granddaddy of gluts: oil.

Oil Glut

On 4/20, while others were getting high, oil got low. Historically low.

The price of a front-month (May) futures contract for WTI Crude Oil (the price that you hear whenever someone quotes the price of oil) went negative for the first time.

To buy a barrel of oil, the seller would pay you $37.63.

If you want the full story, listen to today’s The Daily. For now, I offer an oversimplified explanation of how a negative oil price is possible:

We are consuming less oil, too much is still being produced, and there is nowhere to store it. It’s actually cheaper for oil producers to pay you to store it for them than it is for them to stop producing.

As a result, oil is in the middle of a Coronavirus-induced supply glut.

General Gluts

In macroeconomics, a General Glut refers to situations when there is a lot more supply than demand across the whole economy. The supply/demand imbalance causes prices to fall, causing producers to miss their revenue targets. In response, they actually produce more in order to “make it up in volume,” even though volume was the problem in the first place! This leads to more oversupply, lower prices, and so on.

For centuries, economists have debated whether General Gluts are possible. A Frenchman named Jean-Baptiste Say came up with a law that says that “Supply creates its own demand” (it’s the Field of Dreams Law: If you build it, they will come). Keynes argued that you can solve general gluts by increasing demand through fiscal stimulus (which God knows we are trying). The Austrians disagreed with the premise altogether; they believed it was impossible to have too much of everything.

It’s all quite fascinating if you’re an economist or a policy maker, but I am neither. If you want to learn more about General Gluts, you can head to Wikipedia or Econlib.

As is the case with oil, gluts also happen on a micro level - the glut of specific products instead of a glut of all products. The micro examples are more relevant, instructive, and actionable for people like you and me.

Professor Arnold

For the micro, we’re going to turn away from those eggheads Keynes, Say, and Malthus and turn to the football head, (Hey) Arnold.

In the classic 1997 episode “The High Life,” Arnold’s best friend, Gerald, desperately wants to buy the new B.O.M.B. Rollerblades, but he doesn’t have any money. Instead of mowing lawns or waiting tables like most ambitious 9-year-olds, he responds to an ad promising big bucks for selling Wacko watches.

When he sells his first box out in minutes, Mr. Wacko invites him into the Golden Circle, reserved for the “best salesman.” The Golden Circle entitles Gerald to weekly shipments of boxes that he can then sell at a profit to customers.

Life is good. Gerald is selling watches to everyone and making good money. He gives his sister a dollar because he likes her face, sets up two phone lines in his room, orders business cards, and tells his friends to buy whatever they want from the ice cream truck, on him.

That, though, is when things start to sour. Gerald has already sold watches to everyone in town. His dad has two of them. He even sold a watch to a baby. All of a sudden, he’s stuck with a neverending supply of boxes that keep coming, and no one left to buy them.

Fueled by his own success, he finds himself in the middle of a Wacko watch supply glut. Unsure what to do, he invites his friend Arnold to his house to problem solve.

We’ll come back to the Wacko glut in a minute, but first, let’s look at a real-world example of supply glut happening in real-time.

ZoomGlüt

Virtual event hosts and podcast creators are Gerald.

When shelter-in-place first took effect, creators, community leaders, companies, fitness instructors, chefs, teachers, your friends, your mom, random guys with an idea, and the recently laid-off all had the same thought:

“Everyone is stuck inside. I bet they would love it if I put on virtual events.”

I know because I was one of them. And for a hot minute, I was right.

The first week of quarantine, I hosted five Not Boring Club virtual events. The second week, I hosted eight.

Things started out well for a small, new community. Fifteen people showed up for the first WFH Lunch Club, twenty-five for Trivia, another fifteen for Powerslides.

Riding high, I enlisted the expertise of a few Not Boring members to share their knowledge with people through online events. But even before the first of those started, attendance began to slow. Trivia went from twenty-five to fifteen. WHF Lunch Club went from fifteen people to about four. By the time we got to the knowledge-sharing events, Not Boring members were putting on excellent events to audiences of only seven or eight.

I was bummed. Attendees loved the events, there just weren’t that many of them. I was charging nothing, prostituting myself on social media, spending hours coordinating, building landing pages, designing unique logos for each event, and no one was showing up.

I thought that I was doing something wrong, that the content just wasn’t resonating, that maybe I needed to put on more events - if I built it, they would come.

But then I talked to other people hosting online events, and looked at my own feelings towards yet another Zoom happy hour, and I realized something:

People were overwhelmed by choice, facing Zoom fatigue, and when they did want to engage, they faced a smorgasbord of unbelievable options, for free.

Because virtual events are virtually free to create, everyone rushed to create them. Families hosted weekly happy hours, musicians hosted free concerts, children’s book authors read children’s stories. Even Michelle Obama is reading children’s stories.

Even at zero dollar cost, people didn’t want to attend most Zoom events, because they had to pay with something even more valuable: their time. And, unlike oil, there’s no way to price a Zoom event at negative time. (Well, actually, paying people to attend Zoom events does have a name: work.)

The problem wasn’t with the specifics of the events that anyone was hosting - the events were creative and communal and a lot of fun.

The problem was that together, we created a ZoomGlüt: a dramatic oversupply of Zooms relative to demand.

Just as some oil is still being consumed, some Zoom events are still very popular. But unlike oil, who is throwing the event really matters.

In Status-as-a-Service, Eugene Wei writes about how difficult it is for people new to existing social platforms (like Twitter or Instagram) to build followings without pre-existing follower bases. In a matter of days, Zoom adopted the mechanics of an existing social platform, growing from 10 to 300 million users, nearly as many as Twitter.

And the same thing is happening on Zoom that happens on Twitter: people with a built-in audience are succeeding in attracting people to their Zooms; those without are having difficulty attracting new followers. Michelle Obama would have no problem getting people to watch her read an instruction manual; I would have a hard time getting people to watch me land on the moon.

Zoom events aren’t uniquely glutty. People are producing anything with low upfront and zero marginal costs like it’s going out of style. Podcasts provide a stark example.

At a time when podcast listening is down by 25%, Amazon sold out of podcast mics. Production is increasing even while demand plummets.

This is what happens in a glut - people produce more even as their increased production overwhelms demand. Producing more is clearly not the answer, we need a better idea.

Hmmm… 🤔 what would Arnold and Gerald do in our shoes?

Selling Mr. Wacko His Wackos Back

When we left them, Gerald and Arnold were sitting in Gerald’s box-of-watch-filled bedroom. As they discussed options, they heard a knock on the door. Another week’s worth of watches! Gerald had even more supply, no place to store it, and a customer base that was already full on watches. The glut was on.

Luckily for Gerald, though, his friend Arnold understands people and behavioral economics, and he came up with a plan.

Gerald marched confidently into Mr. Wacko’s office and asked him for more watches. He told him that he couldn’t fill all of the demand he was seeing, that he was selling watches for three times the list price, and that he needed to get more any way he could. He made Mr. Wacko think that there weren’t enough watches to meet all of the demand.

Gerald created the perception of scarcity.

And Mr. Wacko fell for it. Desperate to get his hands on more watches, he bought all of Gerald’s back at double the price, saving the 9-year-old entrepreneur from financial ruin before his 10th birthday.

The Unlikely Success of Clubhouse

So would you believe me if I told you that in a time of supply glut in both virtual events and podcasts, the buzziest new app is one that combines podcasting and virtual events?

It’s true, it’s called Clubhouse, and its success was predictable to students of scarcity.

In Positional Scarcity, the essay that I cite the most, Alex Danco writes that “in conditions of abundance, relative position matters a great deal.” Something fascinating has happened during COVID: digital abundance combined with the disappearance of most of the sources of scarcity.

Porsches, Rolexes, Real Estate, and Fashion don’t mean what they used to. The LA Times is soliciting donations to keep itself alive. Google paid search pricing is 50% or less of its pre-COVID levels. Aggregators like Airbnb and Uber are struggling. Attending Harvard doesn’t mean the same thing when Harvard is on Zoom. (McKinsey Ass-Covering, however, is still going strong.)

In fact, the loss of the traditional sources of scarcity without replacements is one of the reasons we are experiencing digital glut.

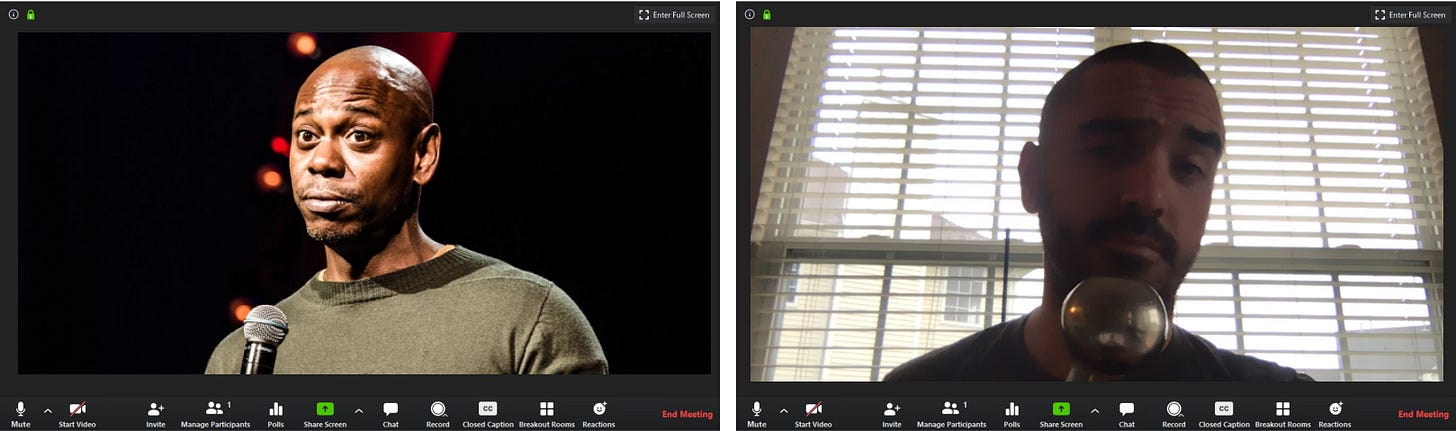

For example, real estate normally acts as a governor on the amount of live comedy shows at any given time. There are only so many stages in New York, and a comedian’s appearance on one of them signifies that they are worth watching. Zoom rooms, on the other hand, are infinite. I’m not funny, but if I wanted to, I could put on a comedy show right now in the same format that Dave Chappelle can.

Without many of the traditional sources of scarcity, the remaining ones become that much more valuable.

The diagram above shows that the only category of scarcity that has survived largely intact is curation. Because of that, curation is even more important than usual. When I talked to him about digital glut last week, my friend Casper ter Kuile, who hosts virtual events and a Harry Potter podcast, said, “I think what we need right now are excellent curators.”

Abundance creates demand for curation. In times of glut, like we are seeing in podcasts or virtual events, curators cut through the noise to tell people what they should spend their time and money on.

Which brings us to Clubhouse.

Clubhouse is an “an audio-based social network where people can spontaneously jump into voice chat rooms together”. Nathan Baschez, a writer and early Clubhouse invitee, describes it as “halfway between a podcast and a party” (or in our case, a Zoom party). But somehow, while both of those are struggling, Clubhouse is thriving!

It’s thriving for the same reason that Gerald was able to offload his watches: the perception of scarcity.

Clubhouse’s founder Paul Davison carefully curated the first group of users from among the most Twitter-famous people in tech and VC. These are not only people he knew others would want to hang out with, but people he knew would signal their involvement to millions, creating a strong sense of FOMO.

Davison’s careful curation created the perception of scarcity by making Clubhouse seem exclusive.

While everyone else is begging “please!” Clubhouse is telling them “no.” It’s the one velvet rope in a world of two-for-one happy hours hawked by overeager promoters.

If Davison had begged everyone on Twitter to join a live virtual conversation, they would have declined. Because he told them they weren’t invited, they wanted in.

FOMO turns people into Mr. Wacko. We want what we can’t have, particularly if we think that others want it, too.

The Takeaway

To recap:

We are facing supply gluts in oil, Zoom events, and podcasts.

The oil glut is caused by a lack of demand; the digital glut is caused by simultaneous overproduction and diminishment of traditional sources of scarcity.

Luckily, Arnold’s friend Gerald faced this problem before, and his response is instructive: in periods of glut or abundance, creators need to create the perception of scarcity.

When I was in high school, I had a crush on this girl. I could tell she kind of liked me, so I leaned in, taking her on coffee dates, buying flowers, and generally making myself abundant. Against all odds, it wasn’t working. I told my dad; he told me to stop talking to her, to make myself scarce. It seemed crazy, but I was desperate so I tried it. And it worked.

COVID or no COVID, the world is becoming increasingly abundant. This crisis has just accelerated pre-existing trends. The rapid acceleration to fully virtual lives has created a digital glut, but the slow and steady progress of technology has already been creating abundance for years, and will continue to do so when this is all over.

And abundance rewards curation and scarcity.

A year before Clubhouse, there was Superhuman, a luxury e-mail service that used a long waitlist to create scarcity and build demand. Fifteen years before Superhuman, Google launched Gmail with a limited beta to only 1,000 users, creating a frenzy for invites. And 44 years before Gmail, in response to increasingly abundant oil, OPEC formed in Baghdad to increase the price of oil by limiting supply.

Even through this turmoil, humans are behaving comfortingly predictably. Whether barrels of oil, e-mail software, or Zoom events, humans devalue what we can have and overvalue what we can’t.

We’re in the midst of a powerful lesson in the power of scarcity, and we do well to remember Gerald and his Wacko watches as we create, build, and sell products and experiences for the remainder of this pandemic and into the abundant future.

Scarcity alone isn’t enough, though. It can get the flywheel going, but it needs to be paired with quality and meet a real need for which customers have real demand. Gerald wouldn’t be able to trick Mr. Wacko twice. It remains to be seen if Clubhouse will be the next great social network or go the way of so many once-exclusive clubs.

The most fun part of being related to me is editing these - thanks Dan, Meghan, and Puja!

Love this essay? Hate it? Have some thoughts? Share your feedback in the comments section. If you enjoyed Wackos and ZoomGlüts, I’d really appreciate it if you shared it with a friend.

Giant COVID Survey

The Giant COVID Survey has been live for four days and we’ve already had over 500 people participate! We’re already seeing some early results that surprise me, and they’ll only get more interesting and representative as more people take the survey.

So far, the feedback has been excellent. People have said “Fun!”, “I actually enjoyed filling that out,” and “I can’t wait to see if people have worn pants more or less than I have!”

Many of you have taken and shared the survey - thank you! For those who haven’t, I’m making the same ask as last week:

We’d love for you to take the survey here

Share publicly: LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Slack groups, your own newsletter - all of it helps!

Share with your family: those overactive family text chains? Drop the link in there and ask your family to participate.

What’s Next

Since no one unsubscribed or called me names, I’ll be sending out another Thursday Edition of Not Boring this week 🥳

We’re going meta, talking about the newsletter business and interviewing someone who recently wrote an excellent post on where it’s heading.

Plus, links, listens, and a book recommendation.

Finally, for accountability (and because I’m having way too much fun with this)…

This week was a great week for the Not Boring newsletter. There are 815 of us now, up 281 (53%!) from 534 just a month ago. Our family grew from 700 to 800 in just 5 days!

We’re getting so close to the 1,000-subscriber-by-the-end-of-quarantine goal that I can taste it. Sooner we hit it, sooner the quarantine ends. I don’t make the rules.

I’m not going to try to create the perception of scarcity on you, you’re too smart for that. I’m just going to ask you to help spread the word by sharing this e-mail with your smartest friends. And once we’re over 10,000 subscribers, you can always say, “I was one of the first 815 and I’ve been here since before it was popular.”

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Man, your writing is fantastic. I was both educated & entertained. Subscribed!

Some of this is also bullwhip effect. While we are facing a “shortage” of things such as toilet paper and sanitizer, we will soon see a glut. This is also happening with the food chain (the glut that is) and producers are throwing out milk and eggs.

On scarcity the book was written by diamond manufacturers. Everyone else is copying it.