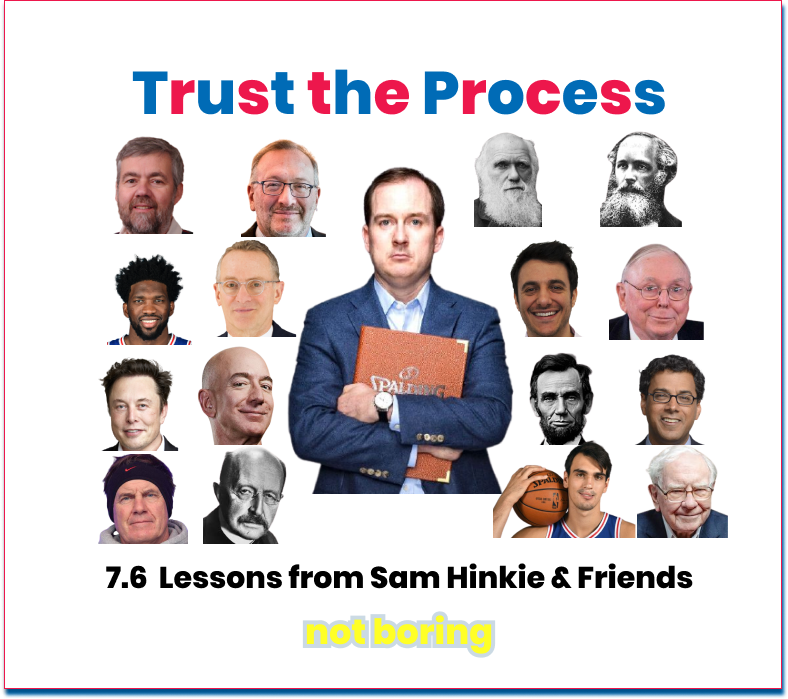

Trust the Process

7.6 Lessons from Sam Hinkie & Friends

Welcome to the 577 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since the last email! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, join 19,190 smart, curious folks by subscribing here!

🎧 If you want The Process in your ears, listen here or on Spotify.

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday! This is, uhh, an important week here in the United States. With nearly 100 million early votes already in, tomorrow is officially Election Day. If you haven’t voted already, let this serve as one of hundreds of reminders you’ll get today across the internet: VOTE. Find the nearest polling place or early voting locations here:

Because it’s not a normal week, I’m not going to write a normal post today. I’ll keep it short(er) and sweet and highlight leadership lessons from my favorite piece of writing: former Philadelphia 76ers GM Sam Hinkie’s Resignation Letter.

I’m a huge Sixers fan, so I’m biased, but I promise you don’t even need to know what basketball is to appreciate Sam Hinkie, The Process, and the courage to do the hard thing in the face of ridicule. As one former Sixers colleague told SI, Hinkie’s approach “could be applied to a draft or an apartment search or a dating website.”

I’ve been wanting to write about the letter for a while, and this week is right for two reasons.

First, last week, the Sixers hired former Rockets GM, Daryl Morey, to become their President of Basketball Operations. Morey made waves last year when he tweeted in solidarity with the Hong Kong protestors, but for our purposes, what’s relevant is that Hinkie was Morey’s protege in Houston before he joined the Sixers. As ESPN’s Pablo Torre put it, “The Philadelphia 76ers kind of just hired their ex-wife’s older sister.” With Morey and new coach Doc Rivers, the post-Process era is officially over, and The Process is back!

Second, tomorrow, the United States is electing a (hopefully new) President. It’s a good time to reflect on what makes a good leader, and Hinkie’s stoicism and peaceful transition out of the Sixers organization is an example that I hope Trump follows. Of course, I abhor Trump because I think he’s morally bankrupt and is willing to destroy Democracy for personal gain. But even if you’re willing to accept his personal flaws, he’s also an inexcusably short-term thinker, constantly trading what’s popular with his supporters today even for what’s in their best interest tomorrow. He’s the opposite of Sam Hinkie. No complex organization can survive a leader incapable of recognizing the long-term implications of their actions, including the United States. Vote.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by…

MainStreet is free money for startups. You sign up and plug in your payroll, MainStreet finds tax credits and incentives that apply to your business, and then they send you money now.

I wrote about MainStreet in September, and maybe you didn’t believe me then. I get it. But since then, MainStreet has found over $1 million for Not Boring readers. That’s $1 million of government money in Not Boring companies’ pockets — an average of $50k — for like 20 minutes of work each.

If you run or work for a US business that does anything technical, you need to check out how much money MainStreet can send you today. You don’t owe them anything unless you get paid.

Now let’s get to it.

Trust The Process

For 1,062 painful and glorious days, between May 10, 2013 and April 6, 2016, my hometown, Philadelphia, transformed.

Known as the type of people who booed Santa Claus, Philly fans started talking about such highbrow concepts as undervalued assets, probabilities, and compounding. Always the heart of pro sports, Philly became the brain.

The reason? Sam Hinkie and The Process.

In Two Ways To Predict the Future, I compared two different types of leaders: Worldbuilders and Shotcallers.

Shotcallers attack big, obvious markets and use brute force and big budgets to win. Shotcallers are like athletes -- Joe Naimath guaranteed a Super Bowl victory, Babe Ruth literally called his shot, and the Yankees spend their way into contention every year. In the business world, Quibi was a Shotcaller. It thought it could use a $1.75 billion war chest to storm in and own mobile video.

Worldbuilders see the way the world should be in the future, lay out a clear vision and unintuitive plan to get there, and patiently execute for years or decades to achieve it, often in the face of vociferous criticism. Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Carta’s Henry Ward, and Stripe’s Collison Brothers are Worldbuilders.

Hinkie is a Worldbuilder.

Hinkie’s Process, his three year term as the Sixers’ GM, is textbook Worldbuilding. He had a vision for an NBA Championship in Philadelphia, charted a probabilistic path to get there, and then did the unconventional, criticism-attracting things required to make it happen. More impressively, he was a Worldbuilder in a league full of Shotcallers. Tech CEOs are supposed to be crazy and future-focused; NBA GMs are supposed to win now.

If Hinkie’s Process is textbook Worldbuilding, his Resignation Letter is the Worldbuilding Textbook. It’s a rare glimpse into the thinking behind a genius leader’s strategy mid-stream, at a moment in time in which The Process was ongoing and the outcome still to be determined, but when Hinkie had no NDA to honor (the letter was supposed to be private) and no fucks to give.

The letter doesn’t seem like it was written by a sports guy. It’s more like a Jeff Bezos or Warren Buffett letter, if Bezos and Buffett retired and no longer had any trade secrets to protect. The lessons in it are as applicable to investing and company building as they are to building an NBA contender. That makes sense. Sam Hinkie isn’t like most sports guys.

Who is Sam Hinkie?

Sam Hinkie sits at the center of my personal interest Venn Diagram: Philly sports, tech, and investing.

Hinkie’s path isn’t like most NBA GMs’. He didn’t play pro ball, or even college. He didn’t work his way up through the ranks. He wasn’t a traditional “basketball guy.” His path looked more like an investor’s, a skillset he brought to bear on a league full of basketball guys.

After graduating from the University of Oklahoma in Y2K, Hinkie spent two years consulting at Bain and another in private equity before getting his MBA at Stanford and heading to the Houston Rockets. There, he served as Special Assistant to the GM, Daryl Morey, the founder of the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference that is the heartbeat of the advanced metrics movement. Morey and Hinkie built a culture and strategy around using statistics and analytical thinking in a league in which most decisions were made based on “eye tests” by “basketball guys.”

Hinkie took his talents to the Philadelphia 76ers in 2013, where he undertook one of the most ambitious experiments in NBA history: The Process.

When the Sixers hired Hinkie, it turned rooting for the Sixers from an exercise in futility, frustration, and boos into a quasi-intellectual pursuit. In the eyes of the fans, Hinkie transformed from a stats guy to a cult hero. Hinkie is a larger-than-life legend among a certain type of Sixers fan (seriously, read this Ringer piece or listen to an episode of The Rights to Ricky Sanchez to understand) who “got it” before anyone else. Any time we landed a high draft pick, or won a game, or advanced in the playoffs, that group shouted, “We were right,” proud that we could understand the long game when no one else could.

The league and Sixers ownership, on the other hand, did not get it. Fed up with losing, after 2.91 years in Philly, they pushed Hinkie out. But people in other fields did; he’s crossed over seamlessly into the world of tech and investing, where he now runs a venture capital firm.

I remember where I was when I knew he’d crossed over: walking across the Manhattan Bridge on my way home from work on a sunny May day, smiling as Hinkie dropped bombs on Invest Like the Best.

It felt like my worlds colliding. Investors appreciate our guy, too. We were right.

On Friday, after the Sixers hired Hinkie’s friend and former boss Daryl Morey, Hinkie did a rare interview, with Pablo Torre from ESPN:

Worlds collided again. Startup people appreciate our guy, too. We were right.

Lux Capital co-founder Josh Wolfe tweeted, “Trust the podcast. Trust the process.” Ludlow Ventures’ Blake Robbins tweeted that Hinkie is by far one of the smartest and most genuine people that he’s ever met, and said that “there is no one better at identifying (and betting on) young talent.” It’s that skill, along with a freakishly analytical mind and a humble courage, that translates so well from sports to tech and investing.

Now, he’s putting those skills to the test in a new arena. In April, he raised $50 million for a new venture fund called Eighty-Seven Capital, which he will manage while continuing to teach courses on Negotiation and Sports Business Management at Stanford GSB.

Hinkie’s approach translates across industries, from sports to tech to investing, and beyond. His tenure with the Sixers and the Resignation Letter he wrote to end it are chock full of lessons for anyone operating or investing in a competitive environment with limited resources. Take the long view, differentiate, and, of course, Trust the Process.

The Process

When Sam Hinkie arrived in Philadelphia, the Sixers were the worst thing an NBA team could be: mediocre. They finished the 2012-2013 NBA season with 34 wins and 48 losses. Even worse, the team had a barren roster and no hope. As Sam Hinkie told ownership, reflecting back three years later, “Your crops had been eaten.”

The Sixers’ owners, private equity people themselves, brought in an unconventional savior to shake things up: Hinkie.

Hinkie’s approach in Philadelphia was as unconventional as his background. SI described it like this: “Hinkie shed his best players and built the Sixers to lose, and then lose some more.” For his first act, on the night of the 2013 Draft, he traded away the Sixers’ one All-Star, Jrue Holiday, for Nerlens Noel, a rookie center coming off an ACL injury, and a future draft pick. Not a popular way to start!

The trade was emblematic of Hinkie’s approach the next three years, which players and fans alike began calling “The Process.” The goal was excellence, not in the moment, or the next season, or even the one after that -- franchises don’t turn that quickly -- but at some point, when the probabilities overwhelmed luck. Good today was out; terrible today for the chance to be excellent in the future was in.

That long-term thinking led Hinkie to do things that critics thought crazy and even wrong, including but not limited to:

Trading away good veterans to make the team worse in the short-term, increasing the probability of landing high draft picks that could turn into franchise-changing superstars.

Stockpiling tons of second-round picks, which Hinkie viewed as one of the most undervalued assets in the league, and maintaining cap space.

Signing injured players who wouldn’t be able to play for entire seasons.

Drafting foreign players and stashing them overseas, where they would continue to develop for years before even potentially playing a game for the Sixers.

The Sixers during The Process were terrible. They set a league record of 28 straight losses during the 2014-2015 season. They were even worse in 2015-2016, racking up just ten wins. But being terrible gave the Sixers hope.

The NBA strives for parity, so the worst teams get more ping pong balls in the draft lottery, giving them a higher probability of picking first. The Cavs were terrible in 2002-2003, too, and that got them LeBron James. Hinkie was gunning for a similar outcome. The Sixers landed the #3 pick in 2014 and 2015 and the #1 pick in 2016 and 2017. They drafted Joel Embiid, Jahlil Okafor, Ben Simmons, and Markelle Fultz - two busts, and two superstars.

Before Hinkie could see the fruits of his labor blossom, though, he was out. Sixers ownership, prodded by a league office fed up with the losing, pushed Hinkie out in April 2016. He was partially to blame; he didn’t even attempt to control his narrative, shying away from the media in order to keep his “light under a bushel” and his secrets away from competitors. But he was also right.

After he left, something magical started happening. While the team botched the Okafor pick (under Hinkie) and traded up to pick Fultz (under Bryan Collangelo in a move that Hinkie never would have made), The Process landed them two cornerstone superstars in Embiid and Simmons. In 2017-18 and 2018-19, the Sixers made the Eastern Conference Semifinals, and were a Kawhi Leonard lucky bounce away from the Eastern Conference Finals.

The Sixers win chart looks like a J-Curve, which occurs when a company spends upfront on something that will take a long time to pay off, but when it does pay off, it pays off really well.

The Process worked. The Sixers haven’t won an NBA Championship (yet), but the probability of their winning one has been higher over the past few seasons than if they had kept fighting conventionally from a position of mediocrity.

(If you want to go deeper on The Process, I got you. One of the first things I ever published online in May 2019 was The First Online Course on the Process.)

Because sports are so public, and the outcomes so clear, The Process provides a clean case study in Worldbuilding. Let’s dive into its lessons.

7 Lessons from Sam Hinkie’s Resignation Letter

On his way out, Hinkie wrote a letter to Sixers ownership explaining the thinking behind The Process. He included ideas from diverse influences, from physicist James Clerk Maxwell to investor Seth Klarman to evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin because, he wrote, “cross-pollinating ideas from other contexts is far, far better than attempting to solve our problems in basketball as if no one has ever faced anything similar.”

The reverse is also true. Cross-pollinating ideas from Hinkie’s time in basketball is far, far better than attempting to solve all of our problems in business as if no one has ever faced anything similar. Fortunately, someone leaked Hinkie’s Resignation Letter.

Here are my seven favorite lessons from the letter and six quick hits from more recent interviews with Hinkie.

1. Take the Longest View in the Room

Taking the longest view in the room means acquiring underpriced assets and building underappreciated capabilities today knowing that they’ll pay off far in the future, when it’s too late for everyone else to catch up. It’s the most important lesson, because the long view unlocks all of the other moves we’ll discuss.

My favorite companies take the longest views. Amazon, Snap, Slack, Spotify, Stripe. In Stripe: The Internet’s Most Undervalued Company, I quoted Stripe CEO Patrick Collison, who said of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos:

There’s something quite deep about the notion of using time horizons as a competitive advantage, in that you’re simply willing to wait longer than other people and you have an organization that is thusly oriented.

Taking the longest view in the room shifts the field of play. As Hinkie wrote, “to take the long view has an unintuitive advantage built in—fewer competitors.” Everybody is trying to sign LeBron James today; very few teams are trying to build up the assets that might give them a chance to draft the next LeBron James in five years. Everyone wants to buy customers via Google and Facebook ads today; very few companies built proprietary growth channels five years ago that are paying off today. Less demand means that those assets are relatively underpriced.

Hinkie also uses Bezos as his example of someone willing to take the long view, writing, “Jeff Bezos says that if Amazon has a good quarter it’s because of work they did 3, 4, 5 years ago—not because they did a good job that quarter.”

Taking the longest view in the room is also just mathematically advantageous. In his book, The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel illustrates the power of time as clearly as I’ve ever seen. He points out that much of Warren Buffett’s success is due to the fact that he’s been compounding money since he was 10, and is still doing it at 90. If he had retired at 60, he’d be worth $11.9 million, not $84.5 billion that 30 extra years of compounding at 22% earned him. If RenTech’s Jim Simons had earned his 66% annual returns for as long as Buffett, he would be worth sixty-three quintillion nine hundred quadrillion seven hundred eighty-one trillion seven hundred eighty billion seven hundred forty-eight million one hundred sixty thousand dollars. Compounding, man.

Worldbuilders take the longest view in the room. They know that to build enduring advantages, they have to accumulate small, non-obvious advantages over time that compound into an unimpeachable competitive position by the time that everyone else catches up.

2. Don’t Get Caught in a Zugzwang

Last week, everyone watched The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix, and now everyone is a Grand Master. So you’ll probably know that in chess, zugzwang is a situation in which having to make a move leads to disadvantage.

At the end of his letter, Hinkie writes, “So many find themselves caught in the zugzwang, the point in the game where all possible moves make you worse off. Your positioning is now the opposite of that.”

To avoid zugzwang, increase optionality. That’s what Hinkie did with the Sixers.

He got rid of expensive, pretty good players and flipped them for high-optionality assets like more cap space (room under the salary cap), draft picks, and young players with cheaper, more flexible contracts. All of that cap space meant teams that needed to dump expensive contracts had to run to Hinkie, who was waiting with open arms, taking contracts off their hands in exchange for more draft picks, cash, and young players.

The canonical example is the 2015 trade with the Kings in which the Sixers took on Jason Thompson and Carl Landry’s expensive contract in exchange for Nik Stauskas, a first-round pick, and the right to swap two first round picks. Hinkie loved pick swaps, which allow a team to swap draft slots if the other team has a higher pick. They’re the kind of nerdy asset that Process fans adored. Take advantage of a team in zugzwang by retaining optionality.

It’s important to note that Hinkie’s strategy worked because he played on a different timescale than opponents. He was happy to lose today to get high draft picks tomorrow, which meant that he was comfortable with a roster full of mismatched parts. A worse roster actually helped his long-term goals!

Cap space and assets represent optionality, and mean that you’re never stuck in zugzwang but can keep playing until the ping pong balls bounce in your direction.

3. Cultivate a Contrarian Mindset

Hinkie cites a 1993 Howard Marks letter to Oaktree’s clients titled The Value of Predictions, Or Where Did All That Rain Come From? In it, Marks laid out an idea that has become Silicon Valley gospel: in order to perform better than everyone else, you need to be both non-consensus and right.

To illustrate his point, Hinkie paints a picture of an investment manager whose job is to grow his clients’ money in a market that’s flat for 30 years. That’s what the NBA is. Every team is fighting for the same fixed pool of wins with the same fixed salary cap. In a zero-growth industry, the only way to grow is to steal share from competitors. To do that, you need to be a contrarian.

With all due respect to all the people who call themselves contrarians, there’s nothing quite like making the hard, unpopular call over and over again while being mercilessly heckled by Philadelphia sports fans. Hinkie was born to handle that pressure. Discussing Joel Embiid’s emergence as a superstar, he told Pablo Torre:

Isn’t that fun to see the world come around to a secret you know that not everybody knows, or a conviction you have that you hold alone from the crowd, and that over time more and more people come to agree?

By taking the longest view in the room and holding contrarian beliefs, Hinkie both secured a high enough pick to draft Embiid and had the courage to draft him despite a navicular bone stress fracture that scared other teams away. Now, the Sixers have a rare superstar (who will hopefully one day get in shape and lead the team to a Championship).

4. Build an Intellectually Humble Organization

The Process got its name from Hinkie’s focus on processes, not outcomes. He would rather his team be wrong for the right reason than right for the wrong reason. Over time, the probabilities favor those who get the inputs right.

It’s easy to get high on yourself when things go right: a big PR hit generates a ton of signups, everyone on Twitter is buzzing about your product, an enterprise client commits to a million dollar contract as long as you change a few things in the product. But Worldbuilders, those focused on a big, crazy long-term vision and the millions of small steps that it takes to get there, need to focus on getting the process and the inputs right. To do that requires the intellectual humility to understand if your early successes are repeatable, and why, and to adjust if not, even if things seem like they’re going well.

To build an intellectually humble organization, the Sixers hired aggressively for people with humility about what’s knowable and what they know. They encouraged a few specific characteristics and actions among the staff:

Be curious, not critical.

Ask questions until you understand something truly.

Don’t be afraid to ask the obvious questions that everyone seems to know the answers to.

Be willing to say, “I don’t know.”

To make sure that your thinking is sharp and that you’re right instead of lucky, Hinkie advocates keeping a decision journal.

Keep score. Use a decision journal. Write in your own words what you think will happen and why before a decision. Refer back to it later. See if you were right, and for the right reasons. Reading your own past reasoning in your own words in your own handwriting time after time causes the tides of humility to gather at your feet.

Checking your reasoning is hugely important for Worldbuilding organizations and for investors. Being right for the wrong reasons leads to overconfidence, and bigger bets based on the same faulty reasoning can lead to ruin.

5. Tolerate Uncertainty

Hinkie is a self-proclaimed Bayesian, referring to a theory in statistics in which you start with an estimated probability of a certain outcome and then keep updating based on new information. When you hear people on podcasts talking about “updating their priors,” this is where it comes from.

In any organization that deals with complex decisions, from an NBA team to a startup, “uncertainties are savage. You need to find a way to get comfortable with the range of outcomes.” That means moving from the three settings that Amos Tversky says most people have when dealing with probabilities -- “gonna happen, not gonna happen, and maybe” -- to the better-defined numerical probabilities that they use in the Hinkie household.

Because most people can’t tolerate uncertainty, they simplify by treating low probability things as impossible. That shuts those options off and decreases optionality. Instead, according to Hinkie, they should apply a numerical probability to an outcome and update as more information becomes available.

This goes from academic sounding to life altering in basketball team building, though. Looking at a player with an estimated 10% or 20% chance of being a star over the next three or four years can’t be written to zero—that’s about as high as those odds ever get.

The name of the game, then, is shrinking the gap between 10% and 20%, and then accumulating as many assets with as high a probability as possible. This is why Hinkie hoarded draft picks instead of trading them all away for one star player. Five players with a 10% chance at becoming a star is better than one player with a 30% chance.

This is the same reason that I’m such a huge fan of Tencent’s approach - investing in a portfolio of promising companies instead of trying to build everything in-house - and why I think that Reliance should follow suit.

It’s also why great early stage venture funds can generate outsized returns despite the fact that 80-90% of their investments will fail. If investors wrote everything with a 10-20% chance of success off as impossible, nothing would get funded, and the huge winners would never get a chance.

6. Maintain a Healthy Respect for Tradition

Hinkie caught a lot of flack during his tenure for getting lost in spreadsheets and not actually watching basketball, to which he responded:

Maybe someday the information teams have at their disposal won’t require scouring the globe watching talented players and teams. That day has not arrived, and my Marriott Rewards points prove it from all the Courtyards I sleep in from November to March.

Hinkie put the burden of proof on the new ideas. He told O’Shaughnessy that if the team’s models told them something, they would check to see if the Spurs did that thing. If the Spurs, the smartest organization in the NBA over the past two decades, did the opposite, he assumed that his models were wrong unless proven otherwise.

Or as he wrote in the letter, “Conventional wisdom is still wise. It is generally accepted as the conventional view because it is considered the best we have.”

In an interview with Tim Ferriss, Stripe’s Patrick Collison said something similar, that while new models of management like Holocracy seemed interesting, most companies should just steal best practices from companies like Google and Amazon and the other proven winners and innovate in the areas like product where doing so would give them a competitive advantage.

7. … and a Reverence for Disruption

In a beautifully patronizing jab, Hinkie told Sixers ownership, “I can imagine that some of these sound contradictory: contrarian thinking, but respect for tradition, while looking to disrupt.”

The yin and yang resolves thusly: knowing where to copy and where to innovate saves energy that can be focused on disruption. Citing the extinction of a flightless bird in New Zealand, Blackberry’s demise, and AI’s ability to beat humans in AlphaGo, Hinkie highlighted that the traditional way of doing things works, until it doesn’t.

Instead of professionalizing the organization and playing it safe, as new management often does, Hinkie told ownership:

We should concentrate our efforts in a few key areas in ways others had proven unwilling. We should attempt to gain a competitive advantage that had a chance to be lasting, hopefully one unforeseen enough by our competition to leapfrog them from a seemingly disadvantaged position. A goal that lofty is anything but certain. And it sure doesn’t come from those that are content to color within the lines.

That’s an important lesson for any NBA team not named the Lakers or any startup going up against a better-funded competitor. When you have fewer resources and are attacking from behind, you need to focus on a few key areas in which they can’t compete.

Hinkie’s whole tenure was a case study in the counter-positioning power from Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, doing something so crazy that competitors are structurally unable to match you. Before Hinkie proved that it was feasible, the Lakers, Celtics, Heat, Spurs, and other perennial superpowers couldn’t tank or trade away superstars to acquire assets in hope of future glory. They were already successful, so they couldn’t take the longest view in the room. The Sixers, though, were permanently mediocre, they had no choice but to mix things up.

.6. Six More Ideas

Hinkie doesn’t talk to the press much, but when he does, he’s verbose and full of wisdom. The seven lessons from the letter skew organizational; six from his more recent profiles and interviews skew more personal -- they’re about how to be the type of person who can lead an innovative, contrarian organization with a long view.

7.1. Figure Out Whose Opinions Matter. Then Ignore Everyone Else. “If you want a few peoples’ opinions to mean a lot, the rest have to mean little. By definition, they have to mean little. If you want these three or thirty people to massively influence your thinking, then these 3 million or 30 million have to be weighted smaller.”

7.2. Be Long Science. Follow Wait But Why author Tim Urban’s three objectives to think like a scientist: be humbler about what we know, more confident about what’s possible, and less afraid of things that don’t matter.

7.3. “Lifelong Learning is Where It’s At.” As is abundantly clear from Hinkie’s website, he likes learning so much that he’s on the hunt for tools that will help him learn even faster. His whole approach is predicated on consuming and making sense of more and better data, and that applies professionally and personally.

7.4. Compound Trust Over Time. Trust grows over years of trust-building decisions. When Torre asked him when he knew that the Sixers were hiring Morey, he replied, “Oh Pablo, the nature of compounding trust with people over a long period of time is being careful about what you say and what you know. I’ll say this, it’s important to me to earn trust with people.”

7.5. “You don’t get to the moon by climbing a tree.” Hinkie patiently bided his time, accumulating assets and increasing the probability of future success. But when big opportunities presented themselves, he went all-in. Two examples: drafting Joel Embiid despite concerns about his health, and dropping everything to focus on his future wife once he met her. He describes choosing who to marry as the most important decision you can make, because it shapes who you will spend most of your time with and what your kids will be like.

7.6. Don’t Repeat the Process

If Sam Hinkie took the reins of the Sixers today, his actions would be different than they were in 2013. The league arbitraged away the advantages he saw back then, the team is in a different position, and he’s evolved.

The Process isn’t about tanking, acquiring second round picks, and stashing players in Europe. It’s about taking the longest view in the room, balancing analysis and wisdom, continuously learning, and having the courage to be truly contrarian with the knowledge that to be better, you need to be different.

That’s why the letter focused not on a prescriptive recipe for re-building The Process, but on a way of thinking about thinking that applies broadly to investing, innovation, and leadership. It’s a handbook for developing your own process.

Trust The Process.

Thanks as always to my brother Dan for editing. What a guy.

It’s been a busy few weeks at Not Boring, and Substack has had some deliverability issues, so if you’re behind and you want to read anything but election coverage:

Thanks for reading, vote, and see you on Thursday,

Packy

this was awesome, thank you

This was such a delight to read.