The Laboratory for Complex Problems

web3 as a simulation

Welcome to the 3,851 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since pre-holidays! Join 96,486 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts (soon)

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Masterworks

I have a confession to make: I can't stop investing in art. It started small. I invested in Basquiat’s Loin in 2020. And I got hooked.

Today, there are 10 paintings in the Not Boring portfolio. I recently added the Picasso masterpiece from the striking image above. Instead of breaking my addiction, my New Year's resolution is to double down and buy as much art as possible, because I believe that art is a key part of a balanced portfolio. Here's why:

UBS reports that two-thirds of high-net-worth collectors buy art for an expected ROI

Real assets like art appreciate well during periods of high inflation

Blue-chip Art prices outpaced the S&P 500 from 1995 to 2021, according to Citi

But even though I’m bullish, I didn't throw down $100 million at auction. I just used Masterworks. They're the fintech unicorn that lets you invest in multimillion dollar works at a fraction of the cost.

And Masterworks has results: they've sold two paintings that netted their investors a 30%+ IRR in 2020 and 2021.

Their offerings tend to sell quickly. Last week, I tried investing in their new $7.4M Banksy painting, but it sold out in less than three hours (and I missed out 🥲). No time like the present.

If you want to join me on the platform and get priority access – click this Not Boring link *

Hi friends 👋,

Happy new year! Hope you all enjoyed your holidays, got to relax and recharge a little bit, and, if you live in New York, that your COVID wasn’t too bad.

Last year, for the first piece of the year, I came out swinging with my only-ever bear case on Bill.com. I was hilariously wrong on the stock: it opened that morning at $137.46 and a year later, it’s up 81.25% to $249.15. It handily outperformed the NASDAQ (+22.3%) and the BVP Cloud Index (-1.8%). It grew revenue 151.9% last year, faster than any other BVP Cloud Index company by far (Snowflake is second at 109.5%). Just clobbered me.

I learned a few lessons from that:

Never underestimate strong distribution, even in the face of a shitty product.

Kick the year off optimistically.

And whew, there’s a lot to cover! I go away for a couple weeks and an all-out war over what web3 is and isn’t, who owns it and who doesn’t, and whether or not it’s total bullshit breaks out.

You know where I come out on this, but words are words. Actions speak louder.

Let’s get to it.

The Laboratory for Complex Problems

2022 is the year that web3 starts making a meaningful impact on atoms-based challenges like healthcare and climate.

Thus far, web3 has been focused on bits, on creating a user-owned internet by infusing physical properties like scarcity, uniqueness, ownership, and self-custody into digital items. That’s an important track; as more of our time, money, relationships, and work goes digital, it’s important that we have the right to own as well as rent.

But all of the wild shit in web3 also serves another purpose. In the immortal words of Allen Iverson…

“We talking about practice. Not a game. Not the game that I go out there and die for and play every game like it's my last. Not the game. We talking about practice, man.”

Expensive Apes? Practice. ConstitutionDAO? Practice. KrauseHouse? We talking about practice. $OHM? Practice. Memecoins? Not the game, we talking about practice, man.

Will the world be a better, more fair and equitable place if my friend Brett succeeds and FriesDAO buys a Subway? No, almost certainly not. But we might learn something about organizing groups of people around a shared mission on the internet that we can apply to the real game. And we might make some more internet millionaires who can fund new projects. Practice.

Every time a new NFT project comes together and falls apart, every time people ape into a seemingly worthless meme, and every time a DAO makes a subtle innovation in an attempt to circumvent some constraint, the whole system evolves and it produces new tools and tricks that entrepreneurs and policy makers can use to attempt to solve large, thorny problems, both digital and physical.

This view of web3 is different than the idea of owning the internet. It’s less about decentralization and censorship-resistance, and more about rapid experimentation of governance and incentive models. It harnesses greed and speculation for good.

In this view, web3 is a global, real-money economic and social simulation, a digital laboratory for complex problems.

To date, the focus and excitement around web3 has been on the bits side: specifically around ownership of digital items and governance among large groups of internet strangers.

Meanwhile, an added benefit is that every new NFT project, novel DAO, DeFi mechanism, and even memecoin is a digital experiment being run in real-time that can also feed back into the world of atoms to help coordinate and incentivize large groups of people to solve hairy challenges.

Bits: building a new digital economy, each attempt is also an experiment.

Atoms: pull the best mechanisms in to solve challenging physical world problems.

Importantly, the digital pieces have value. The total crypto market cap passed $3 trillion this year. ConstitutionDAO raised $47 million. These three pictures are worth over $18 million. There’s real money on the line, which makes people behave like it’s the real thing.

The fact that these are high-price but ultimately low-stakes (the world won’t end if the Bored Ape Yacht Club disappeared) projects is a feature, not a bug. These projects combine internet iteration speed with real-world-huge sums of money to let humanity speed-run simulations on group coordination, all while picking up specific tools to help address hard problems.

Web3 is certainly good at one thing: hurtling large groups of people and money at arbitrary causes. Time to harness that superpower.

From Squiggles to a cure for cancer, Apes to carbon reduction, Punks to saving the fishes.

That’s a big leap. How’d I get here?

Complexity

Over the break, I asked people on Twitter for the one book or essay they’d recommend reading to get ready for the next decade. I wanted to zoom out, think about atoms more than bits for a change, and shake my brain up a little bit.

Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos by M. Mitchell Waldrop, won.

On the surface, it’s a funny winner of the “prepare for the next decade” contest. Waldrop wrote the book thirty years ago, in 1992. It’s not new enough to be expressly written for the next decade, and not old enough to sit among the timeless classics that work in any decade. But the crowds are wise; it was an excellent pick.

Complexity tells the early history of complex systems science through the stories of the founders of the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), “a research institute in Santa Fe that is devoted to the study of complexity in all its forms.” Thirty years later, SFI is still running and complex systems science is still relevant. In October, the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics went to three scientists, “For groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of complex systems" used to create more accurate models of the effect of global warming on the climate.

Complex systems are everywhere, from the climate to the human brain to the power grid to the economy to the beginning of life on this planet from the primordial stew of molecules. They’re devilishly hard to capture in models and differential equations, but crucially important to understand.

Before complex systems science, the prevailing approach to understanding these complex systems was reductionism: breaking them down into their component parts and trying to build a complete picture by adding together each piece. Challenge is, complex systems do all sorts of things that can’t be predicted by looking at each piece. They’re emergent: the whole is greater, and different, than the sum of its parts.

(Incidentally, I think many of the anti-web3 arguments miss by being overly reductionist. I’m actually pretty sure the midwit meme is just reductionism vs. complexity.)

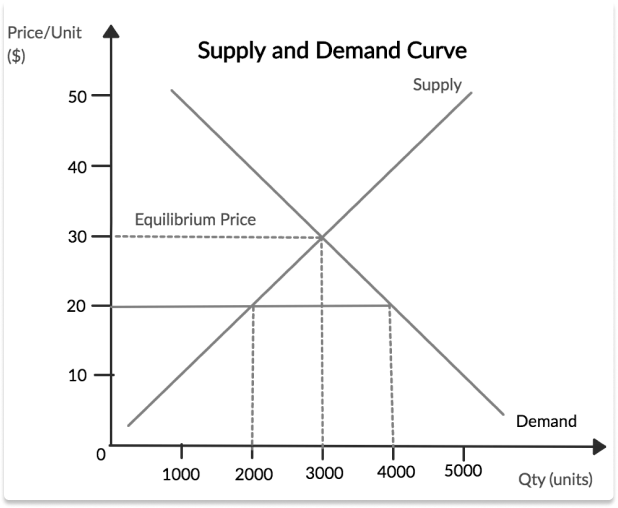

Take economics. The economics that I studied in college, except for one frisky Behavioral Economics course, assumes that “economic man” is perfectly rational and seeks to fit the economy into a series of differential equations and supply-demand curves on top of those assumptions. It seeks equilibrium. It’s mathematically elegant, all fits together, and… is pretty much entirely disconnected from reality.

The real economy, like most complex systems, doesn’t reach equilibrium. It evolves, based on the actions, rational and irrational, of its billions of individual participants.

Grokking the status quo’s shortcomings, and armed with the heretical idea of increasing returns – a concept familiar to all of us in tech today but much less accepted in the early 1980s – Stanford economist Brian Arthur set out to create a new economic framework at Santa Fe.

The stakes were more than academic. The world was coming out of a painful period of stagflation in the 1970s that called into question the Keynesians’ ability to stabilize the economy. A more realistic economic framework would help policymakers and financiers design interventions that would stimulate growth and employment, stabilize the market, and better achieve the goals of their fiscal and monetary programs.

So instead of differential equations based on assumptions, Arthur proposed agent-based simulations:

I had this notion that you could have within your office in the university a little peasant economy developing under a bubble of glass. Of course, it would really be in a computer. But it would have to be all these little agents, preprogrammed to get smart and interact with each other.

Then in this dreamlike idea, you’d go in one morning and say, ‘Hey, look at these guys! Two or three weeks ago all they were doing was bartering and now they’ve got joint stock companies.’ Then the next day you’d come in and say, ‘Oh – they’ve discovered central banking.’ Then a few days later you’d have all your colleagues clustered around you and you’re peering in: ‘Wow! They’ve got labor unions! What’ll they think of next?’ Or half of them have gone Communist.

In practice, there was no Sims-like economic simulation running in Arthur’s office. It was just that, instead of this…

Arthur would let the agents in his simulations run wild, resulting in graphs that look like this:

Complexity Economics: A Different Framework for Economic Thought, Brian Arthur

Beyond math versus simulation, there were a number of major differences between Arthur’s complexity economics and neoclassical economics. In a January 2021 Nature article, Foundations of Complexity Economics, he laid those differences out, feature-by-feature.

In Complexity, Waldrop explained Arthur’s economic agents further: “They would be no more governed by mathematical formulas than human beings are. As a practical matter, of course, they would have to be far simpler than real human beings…”

The Every Icon NFT project that I used in the cover art captures the images I have in my mind for these simulations. Set the starting conditions and a few parameters, and watch what these little dots do.

But what if they didn’t have to be little dots or bits of code, simpler than human beings? What if they could be human beings?

I got the vague sense reading the book, and it slapped me in the face when I saw the table in Nature: Web3 is a complexity economics simulation played out with real human agents and real money.

The Web3 Simulation

Last night, as I was writing this and trying to pull this bizarre idea together, NFT collector and NounsDAO core team member Punk 4156 tweeted this:

Allow me to translate.

2021 was the year of profile picture (PFP) NFTs. Depending on how you value them, both CryptoPunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club have total market caps (# of NFTs * price per NFT) of around $3 billion each. More than just a disconnected network of owners, though, the humans behind the NFT PFP formed communities, online and IRL. First, they met in Discords. Then, they met in-person, at Ape-only events at NFT NYC and Art Basel. They’ve even discussed plans to open up a hotel for Ape owners only.

Now, according to Punk 4156, those communities of people that have come together based on ownership of similar expensive jpegs will start pooling money and investing in other things together. They’ll compete with crypto VCs, using access to the community as potential customers, liquidity providers, and advocates as a competitive edge.

Brian Arthur would be proud. To modify his earlier quote:

Then in this dreamlike idea, you’d go in one morning and say, ‘Hey, look at these guys! Two or three weeks ago all they were doing was trading jpeg pictures of monkeys and now they’ve got a community.’ Then the next day you’d come in and say, ‘Oh – they’ve discovered collective bargaining.’ Then a few days later you’d have all your colleagues clustered around you and you’re peering in: ‘Wow! They’ve got venture capital! What’ll they think of next?’ Or half of them have gone bananas.

Or take the rapid evolution of DAOs. In less than two months, we’ve gone from ConstitutionDAO proving it was possible to raise $47 million from 17,000 people in less than a week to LinksDAO raising $11.8 million to buy a golf course and create an online/offline membership experience. OpenAccessDAO wants to buy and open source academic research papers. BlimpDAO wants to buy one of the world’s 25 blimps. KrauseHouse wants to buy an NBA team. FriesDAO wants to buy fast-food franchises. GasDAO airdropped tokens to people based on how much they’ve paid in gas on Ethereum – a proxy for usage – and wants to turn that group into a coordinated body with a say in the future of Ethereum.

On the surface, existing DAOs range from potentially important to silly to downright dumb. But each one is an experiment in coordinating large groups of strangers around a shared mission, and many add new tricks to the pot.

Do we need a DAO to buy a Subway? Probably not. But FriesDAO is pushing the boundary on how to structure and operate a decentrally owned and governed group of real-world businesses, each with their own P&L.

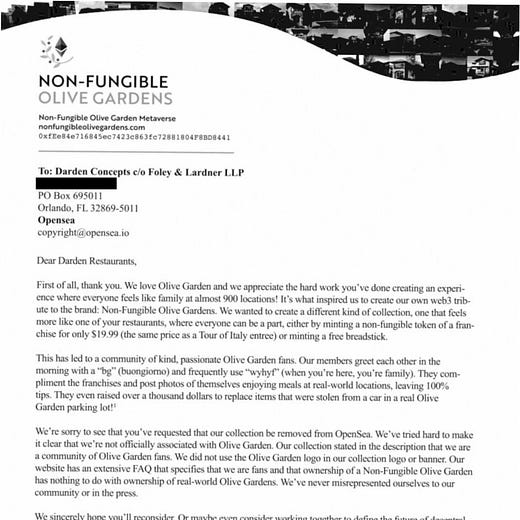

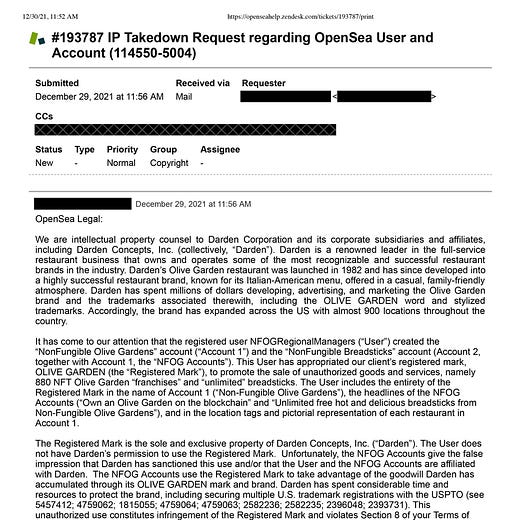

Are Non-Fungible Olive Gardens – literally just NFTs representing each of the world’s Olive Gardens – patently absurd? Yeah, but wyhyf (when you’re here you’re family), and they’re also fighting back against OpenSea taking them down after a takedown request from Olive Garden’s parent company, Darden.

Are many of the people who join DAOs doing it purely for speculation and the hope that the governance token, which confers no ownership rights, irrationally moons? Fuck yeah, 100%.

A reductionist interpretation of all of this might be that most DAOs are kind of illegal and feigning decentralization to get around the law, or that you don’t actually own your jpegs and anyone can right-click save them anyway. A purist might say that speculation isn’t the point, that purely decentralized governance and censorship resistance are the goal and anything else is just a silly distraction.

But a complexity scientist might look at DAOs and NFT communities as a series of real-money, real-incentive experiments that are more accurate to human nature than anything they could build in a machine, and they would learn what levers to pull in order to coordinate internet-native groups of strangers around shared beliefs and shared missions.

And a pragmatist might look at the fact that people have pumped over $3 billion worth of meaning into something as seemingly silly as pixelated jpegs of CryptoPunks, or pushed the value of the $PEOPLE token to $650 million despite losing the bid for the Constitution, or any number of these other things as an opportunity.

They might look at the learnings, tools, software, and money as legos.

And they might look for ways to apply those learnings, and appeal to the same human desires to solve big, complex problems in both the digital and physical world.

The DAOs for the Future

I read two other books over the break, too.

The Code Breaker by Walter Isaacson

Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

The Code Breaker is a biography about Jennifer Doudna, a 2020 Nobel Prize winning CRISPR gene editing pioneer. Ministry for the Future is a fictional novel about the world in the near future if we don’t get our act together on the climate. Both are about complex, atoms-based challenges that we won’t be able to solve with software alone: curing disease and fixing the planet.

In Ministry for the Future, the solution that the titular Ministry devises to the rapidly worsening climate crisis circa 2030 is a carbon-backed global reserve currency, supported by all the world’s central banks, with a guaranteed payout over time. It was a way, the Minister argued, to “go long humanity.”

Life imitates art. We’ve talked about $KLIMA here before, the “carbon-backed algorithmic digital currency” that wants to be a black hole for carbon offsets, making it more expensive to buy offsets, and therefore to pollute. EdenDAO wants to apply a similar mechanism to “future” carbon removals and reductions.

I get to cheat a little bit here, too. Investing in early stage startups lets me glimpse the future. Over the break, I invested in one company working to help a group with a large environmental footprint reduce that footprint using data science, NFTs, and a liquid, open market. I committed to another that’s using a Parent-Child DAO structure to hopefully save lives. (Those are both painfully vague descriptions, but they’re both in stealth so that’s all I can say).

Both have taken bits and pieces from objectively silly past DAO and NFT projects and are applying them in really smart ways. Both understand the fact that open, liquid, global capital markets are a hugely important piece of the puzzle. Neither resorts to high-minded language.

They’ve simply watched the simulations, learned, and taken those learnings to tackle really big challenges. This is why they’ll succeed where previous attempts to “put X physical thing on the blockchain” have failed. It’s not about the blockchain. It’s about the simulations.

Those simulations – played out over thousands of iterations, millions of transactions, and billions of dollars – tell us that greed can be good, that speculation can serve a purpose, that memes have value, and that people are willing to spend money to be part of something bigger than themselves (particularly if there’s the potential for a return).

The fun part about this is that all of it matters: whether you’re trying to solve world hunger, just fucking around and trying some new mechanism, or aping into a project because you like the art, you’re feeding the simulation, adding tools to the toolkit, and pushing future projects forward.

That’s the thing I’m most excited about in 2022: to see all this wacky, wild stuff we’ve been up to online turn into solutions to complex physical challenges.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you next week,

Packy

*See important disclosures and offering circular

The book Complexity was a big influence on Dee Hock, founder of Visa. He writes about it in his book, One from Many: "...I excitedly shared my amazement that concepts now emerging in science were surprisingly similar to organizational concepts that I had been working with for decades."

And if anyone foreshadows web3, it's Dee Hock. Here's what he wrote in 2005:

"If electronic technology continued to advance, and that seemed certain, two-hundred year old banking oligopolies controlling the custody, loan, and exchange of money would be irrecoverably shattered. Nation-state monopolies on the issuance and control of currency would erode."

"...people are willing to spend money to be part of something bigger than themselves (particularly if there’s the potential for a return). " This was the meta lesson that can be duplicated you summed up really well, great article loved it.