Welcome to the 1,018 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, join 16,200 smart, curious folks by subscribing here!

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: Secure the BaaG (Audio) or on Spotify

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by…

As you’ll read today, one of my most strongly-held beliefs is that we are in the earliest innings of a movement towards more accessible, democratized investing across all asset classes. The lines between finance, gaming, media, and social are only going to get blurrier from here. Saying “I don’t really follow the markets” is no longer an option.

But it can also be hard to understand where to start, and to build up a portfolio in a responsible way. That’s where Public comes in. Public makes the stock market social by letting you buy and discuss stocks and the companies behind them with thousands of smart, curious people.

I’ll be discussing today’s essay and the companies behind the trend over on Public. Join me.

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday!

I read a lot -- from sci-fi to 10-Ks to Twitter -- and a bunch of seemingly disconnected ideas float around in my head and interact with each other and sometimes form the fuzzy outline of something that I can’t quite clearly articulate but that feels important to explore. Occasionally, I’ll try to put some of these concepts into words. Today is one of those days.

Today’s essay isn’t meant to be the final or complete picture, but a way to shake up our collective brains and see what insights fall out. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this format, idea, and implications in the comments.

So throw on some Daft Punk…

… and let’s get weird.

Secure the BaaG

Life Imitates Sci-Fi

Would it be possible to run a real business in a way that feels like playing a video game?

This question has been swimming around in my head for the past few weeks, probably because I’ve been reading too much sci-fi.

Before it was a terrible movie, Ender’s Game was one of my favorite books. You should read it, but here’s the plot:

A talented six-year-old kid and two-time murderer named Ender goes to Battle School to train to fight an alien enemy known as “Buggers.” He excels and advances through the tests rapidly. For his final test, a war hero named Mazer Rackham puts Ender through a simulation, first solo and then in command of his classmates, in which his fleet is surrounded by Buggers protecting their Queen’s planet. Ender decides to blow up the planet and wins the simulation, only to find out that he was fighting the real war all along.

That stuck with me since I first read the book twenty years ago. Imagine thinking you were playing a game only to discover that you were commanding armies of real people. Treating war as a video game abstracted away a lot of things -- pressure, moral complexity, fear, individual people -- and turned it into a game that a ten-year-old could win.

Orson Scott Card wrote Ender’s Game in 1985, the same year that Nintendo released Super Mario Bros. on the original Nintendo Entertainment System. When the most advanced video game system was 8-bit, single-player, and 2D, it wasn’t obvious that video game skills would translate to battlefield success.

But thirty-four years later, in 2019, the US Army began actively recruiting video gamers. It even put together an all-Army esports team to compete in Call of Duty, Fortnite, and League of Legends tournaments across the country. As war-based Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs) become more realistic and war is increasingly fought via drones, the skills required to be good at each are converging.

Business has a history of following defense. Many of the once-advanced technologies that underpin the economy today, from the internet to GPS, computers to digital cameras, were first developed for the military before being commercialized by private industry.

Just as Ender’s Game predicted video games’ growing importance in war way back in 1985, Daniel Suarez’s Daemon novels described a future in which an artificial intelligence runs the economy by controlling humans like video game characters. You should read that one, too, but here’s the PacksNotes:

When video game developer Matthew Sobol dies, he unleashes a computer program, the Daemon, on the world. It infiltrates the computer systems of major corporations and governments, crippling them, while simultaneously coordinating the actions of Daemon-sympathetic humans on the Darknet, an Augmented Reality layer that turns the physical world into a video game. By incentivizing humans with points, status, and credits, the Daemon turns civilization into a video game and rebuilds a new economy from the ground up.

Today, three trends are converging to make a version of Suarez’s predictions possible:

Video Games are Eating the World. Video games are worth more than the film industry already, and games are spawning thriving virtual economies.

Business-in-a-Box (BiaB). Software is replacing more pieces of every industry’s value chain, and making it easier to operate businesses at higher levels of abstraction.

Everyone is an Investor. As more assets become more investible by more people, we move up another level of abstraction, to the point where more of our work is a capital allocation game.

Together, these three trends mean that Suarez’s vision is possible, but instead of AI controlling humans like video game characters, humans will run Business-as-a-Game (BaaG). That means:

Game-like Environment with Real-World Implications. One digital interface through which an operator or operators can run a business and lead people, like a MMOG.

High Level of Abstraction. The business should operate at a high enough level of abstraction that goals are understood and important metrics are trackable and actionable, like numeric attributes, health scores, and points in games.

Persistent Environment, Liquid Resources. Because of clarity around goals and metrics, players should be able to join and leave companies on-demand, like Uber drivers with specialized skills, aiding in the quest when most useful.

Rewards Based on Skills and Contributions. People should be able to join companies semi-anonymously, via an avatar tied to a confirmed real identity that is not necessarily visible to the employee (Crucible is making this possible). People will be hired and rewarded based on trackable contributions instead of traditional credentials.

At the simplest level, BaaG is just a shiny new interface on top of existing tools that makes work feel more fun. One way to think of it is, “What if developers built business-in-a-box software in the Unreal Engine?”

As it evolves, BaaG can mean new ways of allocating human, digital, and financial capital to projects, more seamless employment, and new ways of crowdsourcing, prototyping, and simulating products and business models.

While the work will feel fun, challenging, and game-like, the consequences will be real. Money won and lost in the game will be real currency, and real products will be delivered to real customers. That said, Business-as-a-Game is only possible in a world of relative abundance, where basic needs are met and we can afford to spend more time on creative and financial pursuits.

Already, more business runs through software than ever before, and already, virtual economies are real and massive. According to SuperData, virtual marketplaces generated $109 billion in 2019, 85% of which came from the purchase of virtual goods. Virtual economies will only get bigger, and a Metaverse like the one I described in Tencent’s Dreamsseems like an inevitability.

Even before a full-blown Metaverse, though, which may be decades away, software and financialization have already abstracted away so much complexity that certain businesses could be played like Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) today. Instead of quick reflexes, though, the most prized skill will be capital allocation.

BaaG seems far-off, but the pieces are already in place. We just need to tie them together.

Video Games as More Than Games

Video games are having a moment. There are a few obvious reasons, some of which we’ve discussed before:

We’re all stuck at home due to the Coronavirus, and video game usage increased 75%

Unity, the gaming engine that powers 53% of the top 1,000 mobile games, went public at a $20 billion market cap and revealed eye-popping numbers (check out the S-1 Club’s breakdown here)

Epic Games, which makes both Fortnite and the Unreal Engine, is in a battle with Apple over the tech giant’s 30% App Store cut

Matthew Ball has been evangelizing and people in finance are listening

Fortnite has been an absolute monster, with over 350 million players and $1.8 billion in 2019 revenue.

More importantly, Fortnite hints at the possibility for games to be more than games.

Fortnite popularized in the west a popular Chinese business model that we discussed in Tencent: The Ultimate Outsider, namely making games “free to play”and monetizing through in-game purchases of digital items like stickers, skins, and dance moves. In the game, Epic brings together brands and media companies like the NFL, Jordan Brand, DC Comics, Marvel, and more in one digital marketplace. It’s also shown that a game environment can host activities that go beyond playing a game, from premiering the Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker trailer in the game to hosting the Travis Scott: Astronomical concert attended by over 12 million people simultaneously.

While the in-game events are eye-popping and hint to a future in which games are much more than games, in-game purchases are more economically important today.

The $109 billion in virtual marketplace revenue goes both to the platform or game developers, and to individuals and small companies that create digital items for purchase in-game. In games like Roblox and Manticore, users create and monetize not just in-game items, but their own games and their own worlds. In 2020, Roblox expects that its creators will generate over $250 million, and Epic just led a $15 million round for Manticore, a Roblox for grownups.

The definition of a video game is evolving beyond the OED’s: “a game played by electronically manipulating images produced by a computer program on a television screen or other display screen.”

Increasingly, video games and work will blur, and video game dynamics will be an abstraction layer on top of the real world. Just as Ender was able to make decisions without worrying about the details and the Daemon built an economy by incentivizing thousands of participants with Darknet credits, I think that we will be able to run businesses a layer of abstraction up from the way we run them today. Kind of like playing a game.

On the consumer side, there are a few ways in which business and games interact already:

Business Simulation Games

Games like Virtonomics, Capitalism II, and MIT’s Business Simulation Games let players pretend that they’re running a business. I’m as big a business nerd as anyone, and these games seem dull even to me. Job Simulator is funny, at least. It’s based in the year 2050, when humans no longer need to work and instead simulate the jobs of old through video games.

Gamification

Back when I was looking to leave finance to join a startup, I took a Gamification course on Coursera. The Verification I got for completing it is still on my LinkedIn page.

Gamification, as I am now officially qualified to explain, is the application of game elements and digital game design techniques to non-game problems, like business challenges. This means techniques like giving users badges for doing things you want them to do.

We’ve evolved since then, at least according to Superhuman’s CEO Rahul Vohra, who shared “how to move beyond gamification” with a16z. Instead, today, Superhuman uses elements of game design to make the experience of using its product rewarding for users.

Sounds a lot like gamification to me. Either way, since so many companies building consumerized SaaS follow Superhuman’s lead, game design née gamification is once again in vogue. That means that while running a business itself isn’t exactly like a video game yet, the consumer’s experience increasingly is.

Virtual Workplaces

COVID put the burgeoning virtual workspace movement in overdrive. In Zoom, Unity, and the Quest to Scale Corporate Drudgery, Mario Gabriele wrote about the three approaches to replicating what the office does, virtually.

But simulations, gamification, and virtual workplaces aren’t exactly what we’re after. Business simulations are just that - controlled environments with a small set of variables and no real-world consequences. Gamification simply uses game mechanics to make customers (and occasionally employees) do the thing you want them to do. And VR in the workplace is just another environment in which humans can do the work they would typically do in an office.

The question we’re after is whether it’s possible to run an actual business, with consequences outside of virtual worlds, in the same way that you would play a game.

What It Takes to Run a Business Today

As more entrepreneurs build more and better software products to help companies launch, manage, and grow, more of the value chain becomes commoditized. For example, there are multiple software and services companies that handle each piece of the DTC Value Chain.

In Shopify and the Hard Thing About Easy Things, we discussed the idea that the commoditization of the DTC value chain means that it’s harder than ever to stand out from the crowd.

More software has another implication that we’ll focus on today: operators are running their businesses at ever-higher levels of abstraction.

What does that mean? Just like video games allow players to control their characters’ moves by pressing some buttons, B2B software lets operators track and control things that entire teams of employees once did with a few clicks.

But it’s not just ecommerce. Venture capitalist Nikhil Basu Trivedi recently wrote about Business-in-a-Box Platforms (BiaB), including but not limited to Shopify, that “enable new businesses to be started, managed, and grown using their products.” These BiaB companies all take a set of products someone would need to start a business in a particular vertical, bundle them together, and sell them to aspiring entrepreneurs. They abstract away the complexity of building a business, and narrow the set of choices an entrepreneur needs to make.

For Phyllis Schlafly to send her anti-feminist newsletter, she needed to maintain a list of addresses, type up hundreds of copies, stuff and lick envelopes, and send them out through the postal system. For me to send you this newsletter, all I have to do is open a new Substack post (spend 30-50 hours researching and writing) and hit send.

Want to teach people guitar? You no longer need to start a school, rent a space, or put up flyers all around New York City. Just set up a Teachable account, record what you know, set it live, and start making money.

Even massive multinational businesses far too complex to run entirely out-of-the-box are now designing products as involved as cars and buildings within the Unity and Unreal engines, avoiding the time, expense, and imprecision of many rounds of physical prototypes.

Modern software allows business owners and employees to do an increasing percentage of the things they need to do through software, and direct an ever-larger amount of resources at the click of a button. Take Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, for example.

Previously, if you wanted people to perform a task, you had to source, hire, train, and pay each person separately. Today, you can access thousands of peoples’ labor by typing a few keys. This same dynamic plays out in a more personalized way across platforms like Fiverr and Dribbble.

Each of the pieces alone doesn’t seem revolutionary. We’ve been able to contract small amounts of peoples’ time for a while. Digital prototyping isn’t new. We communicate with humans and bots in the same Slack window all the time. Software and automation are integral to modern business and have been for decades.

From inside the day-to-day progress, it’s hard to grasp a paradigm shift. But when you zoom out and look at all of the pieces coming together, the possibilities get exciting. We’re getting close to Business-as-a-Game.

So what would a Business-as-a-Game Look Like?

Business will start to feel like a video game in simpler, single-player industries first, and evolve towards more complex, multiplayer industries over time. Just as video games evolved from text-based single-player games to the visually rich MMOGs popular today, I believe the types of businesses we will be able to run as if they were video games will start simple and single-player and become massively open over time.

In some industries, we’re almost there.

Media

Ben Thompson has written about the idea that media businesses are the first to respond to new paradigms because of their relative simplicity.

Take a single-person media business like Not Boring. What I do is kind of like a game. Every week, I sit at a computer for hours, hit keys trying to unlock combinations of letters that people will enjoy. If I do it well, I get more subscribers, or points. If I do it poorly, I lose points.

The amount of income I generate is correlated with the number of points I have. I can choose to trade my points in today for prizes (by going the paid subscription route) and limit my ability to earn more points in the future, or choose to try to find patrons (sponsors) to support my continued quest for points (thanks, Public!).

I also need to figure out the best way to keep getting more points. Today, I choose to do that by spending more time trying to make the content good and sharing what I write on Twitter, where I pick up another set of points that I can trade for points in this game.

See, it’s kind of like a game. Because it’s just me, and because the metric is so clear, there’s already so little complexity that it’s not hard to imagine what I do as a game. The only difference is the interface.

Because I use a suite of tools, from Substack to Roam to Figma to Twitter to LinkedIn, I know that I’m not in a game. In media, for a new writer or content creator more broadly to think that they’re in a game would mainly just require a new UI on top of all of those tools.

Ecommerce

In my essay on Shopify, I wrote that if I wanted to start a DTC business:

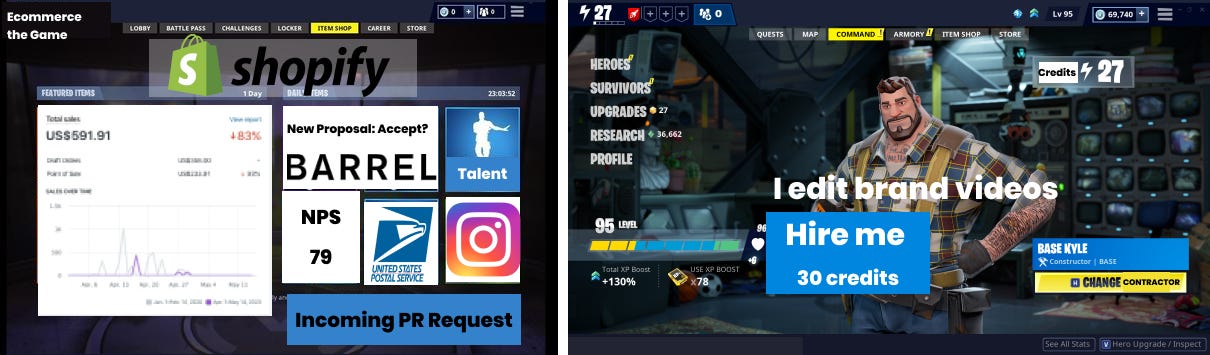

I could find and order product wholesale on Alibaba, set up a store on Shopify, drive customers to the site by buying ads on Facebook, Google, and Instagram, either myself or by hiring a growth marketing contractor on Marketerhire, take payments via Stripe, drop ship directly from China with Boxc or import with Flexport and ship with USPS, answer customer questions on Zendesk or Kustomer, and return items via Returnly.

For a simple product like a t-shirt, running an ecommerce business as a game would also largely be possible today with an abstraction layer on top of all of those pieces of software packaged as a game. I could choose which t-shirt I want to sell from a virtual store, pick a price at which to sell it, create a digital storefront more easily than designing an island in Animal Crossing, and raise points to fund advertising and production by selling digital versions of the t-shirts or presenting my pitch to other players in the game. Once I had enough to allocate towards ads and physical production, I could choose which platform to advertise on and adjust in real-time based on how many points it takes me to find buyers. I might even deal with angry customers whose shirts don’t fit right through in-game chat.

As the company gets bigger and the product gets more complex, so would the game. With a more involved supply chain, more sophisticated marketing, and more angry customers, players could recruit other players to join their team and share in the profits. Jobs would be more fluid, more akin to Mechanical Turk or Fiverr than full-time employment, aided by simplified metrics that new teammates could easily understand.

To get from where we are today to Ecommerce the Game would require:

A rich virtual world in which players could design and render products (Unity or Unreal)

Scoreboards that track CAC, LTV, attribution, costs, and other inputs, respond to user decisions and customer feedback in real-time, and present them simplified as points

An interface that abstracts away administrative complexity - Stripe Atlas presented as “Name Your Business and Pick Your Global HQ” and Ramp presented as a way to spend points and earn rewards

APIs to connect all of the tools that businesses currently use, from Shopify to Stripe to Facebook Ads Manager to USPS, and allow in-game actions to control real-world results

Shopify’s CEO Tobi Lutke is a big gaming fan, crediting some of his success in business to the time he spent playing Starcraft. Might Shopify be the first to develop Ecommerce the Game?

Beyond Ecommerce

Over time, more and more businesses will be able to be run as if they’re games, from real estate to SaaS and even to large-scale manufacturing. As robots replace labor (each robot replaces 3.3 human jobs according to MIT), more business is run via software, and complexity is continually abstracted away, there are very few businesses that won’t be able to be run as if they’re games.

I’m actually surprised that no one has developed game interfaces for running a business yet. When you start to think about all of the disparate, 2D tools we use to work as compared to the rich, contained environments in which gamers play, the way we do things seems bland. And we’re getting to the point at which developing game interfaces for work is technically feasible.

Unreal and Unity make game development relatively cheap and easy

More of the value chain in nearly every industry is run through software and connected via APIs

Looker and other business analytics tools turn messy data into scoreboards that anyone in the business can manipulate and track

Plus, with games being such an unpredictable hits-driven business, many developers would line up for the steady cash flows and high upside represented by B2B SaaS businesses, particularly given those businesses’ recent public market success.

As more of the discrete things we do at work begin to look more like games with persistent scoreboards and simplified decisions, and more of the complexity gets abstracted away, the decisions we’ll make look like investing. Capital allocation will become an increasingly important skill.

At the meta level, this is a manifestation of a growing trend: everyone is becoming an investor.

Everyone is an Investor

At its most abstracted, business is about resource allocation. I invest in thing X, it produces return Y.

The technical trends on the gaming and BiaB software side are converging at the same time that everyone is becoming an investor. Some call it the “Financialization of Everything,” some blame Robinhood, and ex-Coinbase CTO and investor Balaji Srinivasan recently tweeted:

The reason he might be right is that it’s becoming easier and easier to meet basic needs with less effort. Instead of spending months growing and harvesting corn, we spend a second deciding to allocate some of our money to buying corn. According to Our World in Data, over the past two centuries, as we have moved from spending most of our effort on farming, to manufacturing, and now towards investing, our condition has improved:

Extreme poverty declined from 89% to 10% of the world population

Literacy increased from 12% to 86%

Only 4% of infants die within their first five years compared to 43%

That frees up time for higher-leverage pursuits. We spend more of our time at higher layers of abstraction, having gone from extracting raw materials for our own consumption, to trade, to manufacturing, to management, and now, to investing.

We’re essentially playing a video game every day as investing across various asset classes in real-time through digital interfaces becomes more mainstream. We have a certain number of points, and with increasing frictionlessness, we allocate those points to businesses or products that we think will put them to the best use.

Just as operators can run more of their business by clicking buttons, investors can allocate capital to those businesses by looking at numbers. Increasingly, investors means all of us and numbers are real-time. For example, getting a loan used to mean reams of paper, in-person interviews at the bank, credit checks, and auditors. Today, a small business or startup can take out a loan near-instantaneously through Square Capital, Stripe Capital, Clearbanc, or Pipe, all of which read and lend against digitally legible cash flows in real-time.

As regulations relax, software improves, and numbers become instantaneously available, more people are able to invest in more asset classes. Put another way, when everything is financialized, business increasingly becomes a game in which the goal is to maximize the return on allocated resources. As a few examples:

No-Fee Trading Apps. Public makes the stock market social, allowing users to help each other decide where to allocate their money. Robinhood makes stock and options trading feel more like a game.

More Sophisticated Investing Strategies. Soon, Composer will let anyone build, test, and manage automated hedge-fund style portfolios through a simple UI.

Syndicates and Rolling Funds. Syndicates like the Not Boring Syndicate and Rolling Funds, like Jonathan Wasserstrum’s and Austin Rief’s make it easier than ever for accredited investors to invest in startups.

Peer-to-Peer Lending. On P2P lending platforms like Lending Club, people can lend each other money, boosting returns for lenders and lowering rates for borrowers, albeit at higher risk.

Reg A+. Part of the 2012 JOBS Act, Reg A+ lets businesses raise money from a wider range of investors, both accredited and non-accredited, to fund the business itself, raise investment funds, or invests in specific projects. Fundrise is like a real estate private equity fund for all of us who aren’t ultra-high-net-worth, and Rally Rd. and Otis offer investments in cultural items and collectibles like exotic cars, rare baseball cards, and sneakers.

SPACs. Love ‘em or hate ‘em, SPACs mean that companies are going public earlier in their life than they would through a traditional IPO, giving retail investors more exposure to their upside or downside.

Crypto and DeFi. Another love/hate, crypto and decentralized finance enable decentralized funding of companies and projects (remember ICOs?!?), a currency not reliant on central banks, and, let’s be real, the chance to speculate. In the bull case, crypto will mean that money moves at the speed of information, making investing more seamless, which would accelerate the promise of Business-as-a-Game.

As more information, and better tools for interpreting that information becomes available, investment decisions that once required a tremendous amount of time and research require less. As that information becomes more and more legible, and the labor behind the numbers more automated, it becomes easier to think about everything as a potential investment opportunity, and business increasingly becomes a game of capital allocation.

Business-as-a-game won’t entirely be about capital allocation. There are things that humans do extraordinarily well, and the people who do those things will be in high-demand on the receiving end of the allocated capital.

Our time and skills are becoming more liquid and legible. Just as people completed tasks for Darknet credits in Daemon instead of holding down corporate jobs, we will behave more like players in video games, with our skills on offer to those who need us to complete their quests. In a liquid enough market, that means more earnings potential for us and more efficient resource allocation for the people running Businesses-as-a-Game.

This is kind of dystopian, no?

A world in which we operate as characters in a game seems kind of dark, but as technology changes and gets more high-fidelity, norms change with it. Two centuries ago, when farming was the most common profession, it would have been unfathomable to think about a world in which most people sat inside, hit a metal box all day, and rarely touched the product of their labor. Even ten years ago, it would have seemed crazy to do everything over video, or chat cross-company on Slack, or build businesses on YouTube or Instagram or Twitch. But we evolve and adapt. We keep the best parts, throw out the worst, and keep going.

Ultimately, I think that business needs to become more gamelike, for three reasons:

First, in time, it will seem barbaric that we didn’t enjoy going to work. As more of our basic needs are met automatically, we should be able to spend more time on things that we enjoy doing.

Second, when our basic needs are met, we will need a sense of purpose. The beauty of games is that they lend importance to the objectively trivial. If we reach a level of abstraction in which we all become investors, sending money back and forth, wrapping it in a game will make it feel more meaningful.

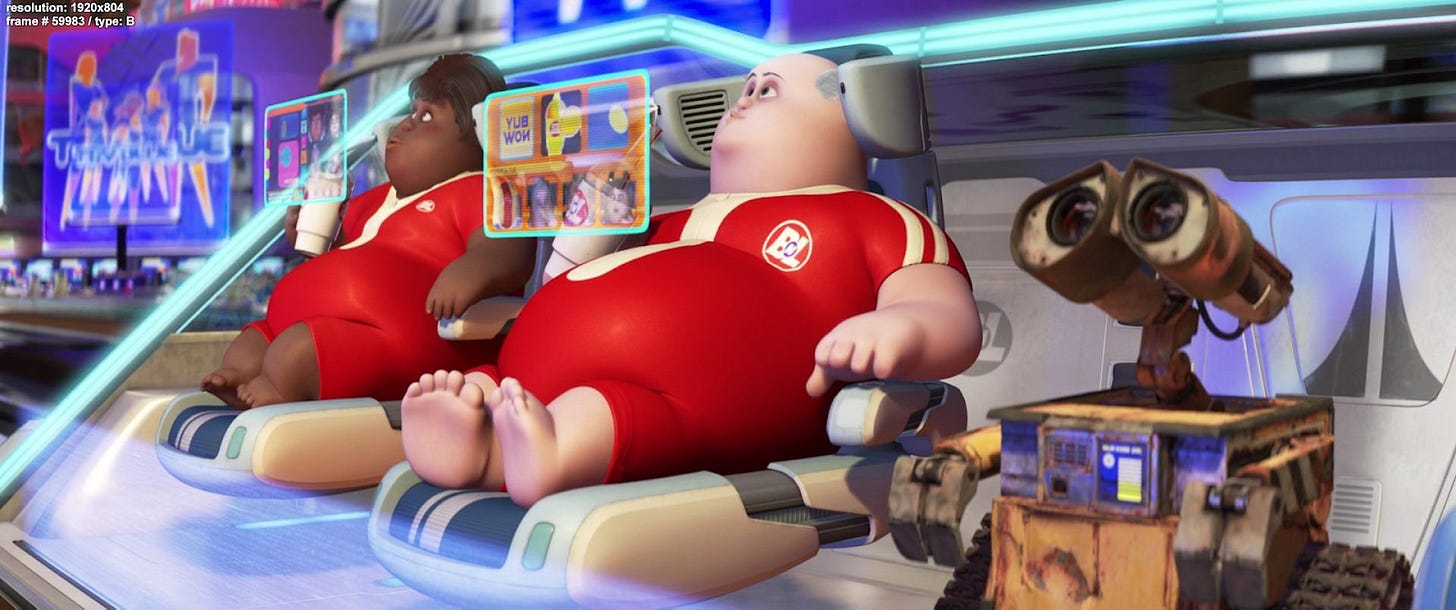

Third, BaaG gives humans more agency than a future in which AI and robots are able to do everything that humans do now, however far in the future that day may be. By becoming part of the game, we can avoid the Wall-E future that I constantly dread.

I’m a techno-optimist, which is why I think that the march towards evermore abstraction is generally a positive, but I do think we will need new ways to find meaning as business becomes decreasingly life-or-death. Business-as-a-game is one path.

BaaG is also one of the reasons I’m so bullish on tech, and that I really believe many category-leading tech stocks are still undervalued. Companies like Tencent, Shopify, Snap, Stripe, Google, NVIDIA, Unity, Amazon, and many more will benefit tremendously as not just the way we shop, but the way we run businesses continues to evolve and move online.

I don’t think that we’ve even scratched the surface of their potential, or that people fully appreciate how big the leading tech companies are going to become. That’s why it’s fun to get a little weird and expand our universe of possibilities.

Thanks as always to Dan and Puja for reading some truly terrible first drafts and helping me write something I’m excited (but still a little nervous) to share with all of you.

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday,

Packy

As long as equitable resource allocation isn't a reality the gamification of business represents a clear and present danger of amplifying things that businesses already do poorly - namely accounting for external offsets and addressing the ethical questions of capital allocation.

The part about warfare seems emblematic here - the goal of war isn't, and shouldn't be, to hit kill metrics or make bombing fun. The goal of war is to win. But the current drone warfare paradigm can't lead to a "win" because it's ameliorative not decisive - its targeted nature against suspected terrorists keep US criticism of the effort to a minimum while ensuring its use as a policing tactic. Because it is less visible for American citizens the abstraction of war into its constituent parts reduces awareness of its costs economically, politically, and socially. The result: 20 years after 9/11 the US has bases all over the Middle East and North Africa deploying drone bombings against suspected terrorists every day. Abstracting the process of war-making into its constituent parts has led us to abdicate the more fundamental question: what the hell are we doing here and what are we trying to achieve?

My point: To continue the analogy, you're going to need two games, the game of the business and the game of the leader, whose domain must be substantially larger than that of the business. Look at how the oil market is going - in the real world you can hit all of the metrics in your game, and still lose. The leader's role is to look at the metrics being used at the business level and assess them against their broader implications for the goals, health, and direction of a business. The leader's role isn't to hit metrics, it's to endlessly create and optimize the businesses metrics while answering to the demands of the shareholders and broader society. Two social impacts of import seem immediately apparent - fair labor and climate impact.

If you turn J Crew into a clothing company simulator, for instance, you ratchet up abstraction of business processes to the point you might lose the map of where your corporation exists within the social milieu entirely. Conventional financial models ostensibly make this game exclusively about producing clothes, shipping them to retailers, and marketing them effectively. What are the odds that such a game can answer questions like: Who's making the clothes, where, and for how much money? What's the climate impact of product lifecycle? Where do the clothes go when consumers are done with them? If your focus is on maximizing profitability within the conventional financial model your business risks adverse effect from unintentional offsets and stringent regulation.

In the end, businesses must play two games to avoid abstracting away social responsibility - anything less will be at the cost of all stakeholders. The viability of the biggest game, the economic game we play to ensure everyone an equitable distribution of resources in the first place, is at stake.

Inevitably, responses to a post like this turn into a hobbyhorse. I'll try not to.

My background is in user research, including how people interact with systems, and I'm also an expert on game design: not video, but tabletop, including a lot of economic, conflict, and "serious" modeling sims. The main problem with "business as game," by no means a new idea, is that games of the type you propose here are finite, not infinite; discrete, not continuous. They are interfaces that are contiguous with models. This is an excellent way to understand a problem space, but not to engage with or transform a problem space. Put another way, it's suicide to run a business AS a model. You use biz models to UNDERSTAND the business. If your business is contiguous with its model, it's trivially easy to copy or, increasingly, to automate away. So in this regard, yes, you could put together a (really unfun) "game" of your glued-together martech and newsletter and IFTT stack. The reason nobody copies it is that it's too small-time, until you get the brilliant idea to sell it to other people via an online course and becomes the industry SOP overnight, incidentally destroying the (small) value of your initial newsletter-guy-stack advantage and ensuring your course will quickly become free. So it goes.

Larger spaces, actual corporations, are intractable to this kind of modeling for hundreds of reasons. The main reason, hard to talk about in our supposedly egalitarian age, is that if you can actually put this kind of thing together--it is nontrivially difficult if you want nontrivial results--"business" is probably the last place you want to be. Actual game companies, think tanks, university research centers, your own unicorn...vs. trying to automate the bureaucracy of people who are indifferent or actively hostile to your efforts, for trivial sums of money. The career of Jim Dunnigan is especially enlightening in this regard.