Robinhood Robinhooded Robinhood

Chaos was inevitable. What now?

Welcome to the 517 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 31,873 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen here or on Spotify (in about an hour).

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Future

Two weeks ago, I told you about Future, the 1-on-1 remote personal training app I’m using to fight off the dad bod. I shared my workout stats publicly to give myself some extra accountability, and it worked: I haven’t missed a workout since that email.

Lest I get too comfortable, last week, Future upped the intensity by introducing Challenges, a global competition to hit 21 workouts with your friends. I have a bet going with Future’s CEO Rishi and friend of Not Boring Mario - whoever gets there first gets a share of $RBLX from the losers.

Join in on the Challenge and get your first 45 days of Future coaching free by signing up with my personal Challenge link:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

Last week was not normal. Your mom is asking you to explain Reddit and Gamma Squeezes in the same sentence. The markets feel unstable in the most internet-y way possible. So this won’t be a normal newsletter.

If you write a newsletter that covers tech and finance, you kinda have to write about Gamestop / WSB / Robinhood. That means that plenty of really smart people have written great analyses. See: Jill Carlson, Matt Levine, and Alex Danco for some thorough and thoughtful takes.

But I haven’t yet seen the take that I want to read: that this was inevitable. Given how Robinhood built and incentivized itself, it would have taken a black swan event for the company not to end up in this situation at some point. And it’s only going to get crazier.

Let me get this out of the way upfront: I am clearly conflicted here, on both sides. Public has sponsored Not Boring, the Not Boring Syndicate invested in Composer, I know people who I like and respect who have invested in Robinhood, and I trade some of my money in Robinhood.

None of those facts change the way that I think about this situation. I have the paper trail to prove it. I’ve been expecting this for years!

The Robinhood story is a story about risk and chaos. If you introduce more chaos into the system than you’re ready to handle, the chaos is gonna getcha.

Let’s get to it.

Robinhood Robinhooded Robinhood

Do not be deceived: God is not mocked, for whatever one sows, that will he also reap.

Galatians 6:7.

Financial Chaos is a Ladder

Finance isn’t about good or evil. It’s about risk management. Hedge funds aren’t evil, Wall Street banks aren’t evil, regulators aren’t evil, retail investors aren’t evil. That’s one of the beautiful things about finance. It’s not about value judgments. It’s about numbers.

Robinhood isn’t evil, either, it just made a risky bet with tremendous upside potential, kind of like the bets that many Robinhood traders make every day. Robinhood bet that it could introduce tremendous amounts of risk into the financial system, push all of it onto its users and the market at large, and insulate itself from the consequences.

And it would have gotten away with it too, if it weren’t for those meddling kids!

In the good old days, circa a week ago, when Robinhood was still Robin Hood and st0nks only went up, there was a meme that circulated every so often about what would happen to the market when Robinhood went public and Robinhood traders could trade Robinhood shares on Robinhood. Woah.

It reminded me of that scene in Being John Malkovich, the one in which John Malkovich goes through his own portal and ends up surrounded by other John Malkoviches who can only say, “Malkovich.”

Robinhood Robinhood Robinhood.

There was also a meme, less cartoon and more condescension, among more serious markets types about what would happen to Robinhood traders when they got too long on margin and the market finally turned against them. They’d Robinhood themselves into financial ruin.

Robinhood, this idea went, made it too easy for unsophisticated investors to trade on margin (borrow money to buy stocks or options). That works really well when stocks go up, and really poorly when they go down.

If you own a bunch of stocks on margin, and the price of those stocks drops, you get hit with a margin call, and need to put up more cash, or sell the stock. Margin calls can be a killer, forcing traders to unwind at exactly the wrong time and lose a ton of money.

Robinhood knew that the people who traded on its platforms (I hesitate to call them customers, because “if you’re not paying, you’re the product”) might get hit with margin calls, or might wipe themselves out by trading options without fully understanding them, or do any number of things that could lead to huge losses. And they did. The most infamous and tragic example occurred in June, when 20-year-old Alex Kearns committed suicide after mistakenly thinking he owed over $730k due to margin trading.

But Robinhood, and I hope you’ll pardon my French here, did. not. give. a. fuck.

Until now, Robinhood has been able to push all of the risk it facilitates onto its users and to the market at large, and hide behind language about market democratization.

The markets, it turns out, do not give a fuck either. Numbers are numbers. Words are just words.

The delicious irony of last week is that by encouraging so many of its customers to make risky trades on margin, Robinhood Robinhooded Robinhood. It took on too much risk itself, got hit with a margin call of its own, and was forced to reveal whose side it was really on - its own. Them’s the breaks.

This was bound to happen, and it will happen again. Every move that Robinhood makes seems to increase entropy in the system by encouraging riskier and riskier behavior by retail traders. While it would have been impossible to predict exactly how this would go down, it was very easy to predict that something like it would. That’s the nature of chaos.

Today, we’ll cover:

We’re All Idiots. Me included.And options trading is really hard.

How Robinhood Makes Money. Looking at Robinhood’s incentives.

Robinhood, WSB, and Entropy. A look at Robinhood’s history and chaos.

Robinhood Robinhooded Robinhood. What happened last week?

Where Do We Go From Here? Will Robinhood end up like Uber or Napster?

Please don’t get me wrong here: I firmly believe that people should be allowed to manage their own money. That genie is out of the bottle, thanks in large part to Robinhood, and that’s a good thing overall. It’s just that, if you’re going to facilitate and profit from chaos, don’t be surprised when that chaos turns back on you.

We’re All Idiots

Let me start out with a personal story that colors my views on all of this.

I started my career at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in 2009. When you work at a financial institution, they put all sorts of restrictions on your ability to trade: you need to get approval to buy stock or options on a specific company, you have to hold for thirty days, etc…

The intention of the rules is to protect the bank. Banks don’t want their employees trading on insider information, of which there is necessarily plentiful amounts floating around. But those rules also protected me.

When I quit in the summer of 2013, I owned a portfolio of stocks that I wanted to own for a long time. Facebook at $19, Tesla at $29, Apple at a split-adjusted $15. I even owned 38 Bitcoin at ~$100 because they weren’t subject to the bank’s restrictions. The list goes on, but I’m getting nauseous just writing it out.

Quitting meant no more restrictions. Time to make the real money. I logged into my Merrill Edge account and applied for access to options trading. I checked all the boxes -- good salary, professional experience with options, Series 7 and 63 licensed, recently employed by Merrill itself -- and there was still a bunch of friction, but I finally got approved to trade options.

Want to guess how the story ends?

I got my ass handed to me. I made all of the rookie mistakes, like buying short-dated Apple calls into earnings, as if I had an insight that the millions of traders who watch Apple every day missed. Apple beat earnings - woohoo! - and my calls went to zero. My premium got wiped out by the vol crush. I wasn’t trading; I was gambling. Thankfully, I wasn’t trading on margin, or things could have gotten out of hand quickly.

I tell you all of this for a couple reasons:

No Judgment. I don’t look down on “Robinhood Traders.” I’ve been there.

Options Are Hard. I was relatively sophisticated on paper and still got crushed.

I Know How This Story Ends. Trading naked calls when they’re going up is the most fun thing in the world; when they’re going down, it’s the least fun thing in the world. And Robinhood is in the fun business.

My views on Robinhood are not colored by some patronizing opinion that other people -- retail traders, Redditors, the WSB crew, whoever -- are some special class of idiot not capable of options trading. We are ALL idiots.

Even the hedge funds who trade options don’t do it based on the opinions of some special class of genius. They do it based on systems that allow them to predictably hedge risk, hence the “hedge.”

If you’ve heard about Gamma Squeeze for the first time this week, for example, it’s made possible because hedge funds hedge. Here’s what it means:

If someone is buying a call option, someone else is selling it. That person theoretically has uncapped downside risk, since a stock can theoretically go to infinity dollars.

To hedge that risk, institutional investors who sell call options also buy the underlying stock to offset the risk based on something called “Delta,” which describes how sensitive an option is to a change in the price of the underlying stock. (They also Delta hedge if they buy an option, since they don’t want to take directional risk).

If the Delta is .20, the price of the call is expected to move $0.20 for every $1 move in the underlying stock, so the option seller would need to buy 20 shares to hedge the risk on the contract (options contracts are 100 shares).

With me? Ok. Well as the price of the underlying stock changes, so does the Delta. The rate of change of the Delta is called the Gamma. Roughly, Delta measures speed, Gamma measures acceleration.

All else equal, Gamma increases the closer the price of the stock is to the strike price of the call option, which means that as you get closer to the strike, Delta increases more quickly and the call seller needs to buy more underlying, faster, to stay hedged.

That drives the price up faster, too, as more people buy the stock, which means call sellers need to buy even more underlying to remain hedged, and so on. That’s the Gamma Squeeze.

Still with me? That’s just one thing that happens with options, and probably the sexiest because acceleration is sexy and it works with you if you own the call. But to really understand options, we need to understand more Greeks, too.

Theta deals with time - how the price of the option moves as it gets closer to expiration.

Vega deals with volatility - the more implied volatility, the more expensive the option. Vega explains the “vol crush” that wiped me out when I traded Apple calls.

Rho deals with interest rates - options prices are sensitive to interest rates, too!

I’ll stop, but I hope my point is clear: this shit is complex.

Given all of that complexity, Robinhood’s options interface mayyyy be a level of abstraction or two too high:

Depending on how you look at it, that’s “democratizing options trading” or making it way too easy so Robinhood can make money.

How Robinhood Makes Money

“Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

Robinhood is clearly incentivized to get its users to take on risk; last week’s outcome was inevitable.

Robinhood designed its product to encourage and facilitate margin and options trading, because that’s how Robinhood gets paid. It makes money in five ways:

Selling order flow to hedge funds (“payment for order flow” or “PFOF”). They typically make more by selling options order flow than equities order flow.

Selling Robinhood Gold subscriptions for $5/month.

Providing margin to customers at a 2.5% interest rate (down from 5% in December).

Lending out securities to counter parties who want to short it.

Earning interest on cash balances.

Let’s cover PFOF first, because it’s one of the most controversial and misunderstood issues surrounding Robinhood. PFOF is not inherently bad, and most brokerages do it. Here are two fun bits of history, though:

Know who came up with the idea for PFOF? Bernie Madoff. Yup.

Citadel, the largest buyer of Robinhood’s flows, wrote a letter to the SEC in 2004 arguing that PFOF should be banned. lol.

Additionally, Robinhood makes more money for selling its order flow than most brokerages. FinTech Today asked some experts why that is back in July, and the answer comes down to three things:

The type of trader on Robinhood: easy for funds to assume they’re all unsophisticated given the simplicity of the interface, whereas it’s harder to tell on other platforms.

What they trade: a ton of options, many with wide bid-ask spreads

How Robinhood charges: a % of the spread vs. a fixed fee for most brokerages.

Benn Eifert put it succinctly: “The profitability of order flow determines its pricing power. The product is the user, and high volume of non-toxic (uninformed) order flow in high spread options trades is highly profitable.”

Saying Robinhood traders are unsophisticated isn’t mean; it’s facts. The market puts a price on how bad the trading on each platform is, and it pays Robinhood more than anyone else.

The fact is, value judgments aside, the company is clearly incentivized to get people to trade more often, to trade more options, and to trade on margin. The ideal trader on Robinhood, from a revenue perspective, is a Robinhood Gold subscriber who frequently trades options on margin. That also happens to be the riskiest kind of trading behavior for the individual traders themselves.

When things go wrong, which they inevitably do, and someone criticizes Robinhood, the company hides behind the guise of democratizing access to the markets, saying something like:

It’s a free market! They’re adults! Are you saying they aren’t entitled to the same wealth creation opportunities as the big fancy hedge funds just because they weren’t born rich? We’re on the side of the little guy! Whose side are YOU on anyway? Elite…

This is Silicon Valley 101. It feels wrong, using slick and disingenuous marketing to obscure misaligned incentives, but all of the big tech companies do some version of this. As long as it operates within the legal and regulatory bounds, though, Robinhood is able, and even fiduciarily obligated, to do whatever it takes to maximize shareholder value.

But, as last week showed, Robinhood is also subject to the savagery of the market. It can’t externalize all of the real risk it generates with words alone.

Robinhood, WSB, and Entropy Theory

In 2013, two Stanford grads, Baiju Bhatt and Vlad Tenev, founded Robinhood, based, so the story goes, on two simultaneous events: Occupy Wall Street and the rise of mobile. They set out to build a mobile commission-free trading app that “untethered the financial markets from the typical computer setup with multiple monitors.”

Between 2013 and 2017, Robinhood was a typical Silicon Valley startup. It used technology to make trading easy, and introduced innovations like commission-free trading and fractional shares, which genuinely democratized access to investing.

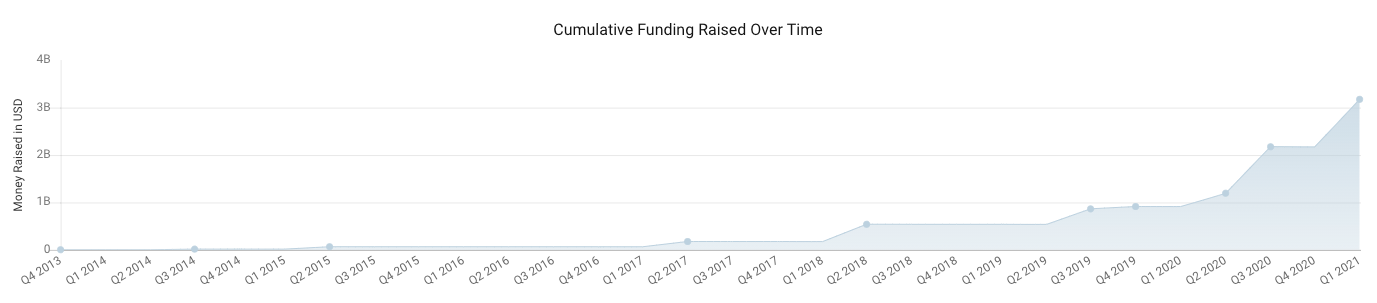

By 2017, Robinhood had raised a little under $70 million. In April 2017, it became a unicorn when it raised a $110 million Series C at a $1.3 billion valuation from DST after crossing the 2 million mark and growing its Robinhood Gold Subscription product. Between the C and D, Robinhood introduced two products that would help fuel its growth - commissions-free options and crypto trading. In December 2017, when they rolled out options, I predicted how this was going to end.

In May 2018, it raised a $363 million Series D at a $5.6 billion valuation. More than 3x growth in valuation in eight months implies that options trading was working well for the company, but it also introduced a whole new level of risk, for users and for the company itself.

Between the Series C in 2017 and the beginning of 2020, Robinhood grew steadily from 2 million to 10 million users. Then COVID hit, and things started to get really interesting. Robinhood added 3 million users in the first three months of the pandemic. By October, akram’s razor estimated it had 16 million users.

Meanwhile, a small subreddit called WallStreetBets, also started in the early 2010s, was growing slowly and steadily, too. Up to this point in the story, WSB and “Robinhood Trader” were practically synonymous. The terms both meant something like “particularly risk-seeking retail YOLO trader.” WSB fed off of Robinhood, and Robinhood fed off of WSB. Robinhood’s growth mirrors WallStreetBets’ almost perfectly.

With Robinhood as their perceived brokerage of choice, in the very beginning of the pandemic, the WSB crowd stopped just talking and started pumping stocks like Lumber Liquidators, using the seeds of the tactics, like buying up OTM calls, they would eventually bring to bear on $GME.

All through 2020, I watched both Robinhood and WallStreetBets. I thought they were both part of a larger shift, not just a temporary blip. The thesis of Software is Eating the Markets, which I wrote in October, was that:

Software is eating the markets. Flush with cash and empowered by new tech platforms that blur the lines between investment, experience, entertainment, and digital assets, a segment of consumer investors are shifting money from consumption to investment.Consumer investors expect different things from their investments than professionals do and value assets differently as a result. New technologies, regulations, social trends, and asset classes mean that this shift is here to stay, and could continue to gain momentum after COVID is gone. This time, maybe it really is different.

Retail traders value different things than institutional investors, and the experience of investing in and rooting for companies together is a non-trivial piece of the equation. In June, in Business is the New Sports, I wrote:

If current trends persist, and retail investors (you, me, and everyone else on Robinhood and Public) continue to move the markets, then stock prices will be impacted more by fandom than fundamentals than they ever have before.

I started getting a little skeptical about Robinhood later that month, though. In The Will Ferrell Effect, I included Robinhood in a group of “Meme Startups,” writing:

Robinhood’s failure to build critical infrastructure and support before it went viral caused the app to fail on the market’s most volatile days, and contributed to a young trader’s suicide.

In July, The Margins’ Ranjan Roy wrote a post called Robinhood and How to Lose Money in which he argued that:

Robinhood had too little friction to encourage good trading

The company, while not intentionally evil, prioritized growth over all else

Robinhood traders were “the gravy,” the unsophisticated counterparties that Wall Street sales people relied on to trade more at worse prices.

He also pointed out that because of Robinhood’s business model, it makes more money the more people trade, which again, is not inherently bad, but colors how you look at everything they do. Robinhood is designed in a way that increases entropy, or chaos, in the financial system.

On July 20th, partially inspired by Robinhood, I wrote a piece called Entropy Theory, in which I argued that markets and industries get more chaotic all the time, and the companies that win are the ones who wrangle the entropy, not the ones who create it. On July 23rd, in my investment memo on Composer, which is admittedly biased but nonetheless honest, I applied it to Robinhood:

I think that Robinhood might be Napster. It’s not wrangling entropy; it’s creating it. It uses game mechanics to get less sophisticated traders to trade more, and makes wacky things happen in the market.

Since then, I watched (and tweeted) as the theory played out:

October 7th: I noticed that Robinhood rolled out recurring investments (they launched in May). There’s nothing unique or wrong about that, and dollar cost averaging is actually smart, but with recurring investments, they can sell funds a calendar of when their users are going to be buying which stocks, weeks and months in advance.

October 16th: Robinhood emailed users to tell them that they were increasing margin requirements due to election volatility the next day and that they would be hitting users with margin calls if they didn’t adjust by the end of the day.

December 11th: Robinhood rolled out a new feature allowing users to buy options on the day they expire. Buying options on expiry day is straight gambling.

December 16th: Robinhood was accused of “gamification” of trading by a Massachusetts regulator.

Throughout the pandemic, Robinhood continued to up the ante and introduce more risk in the name of democratizing access to investing. All of it brings us, predictably and inevitably, to the events of last week.

Robinhood Robinhooded Robinhood

On Thursday, January 21st, I got a text from my friend who spends the most time on Reddit:

The twoposts he sent me have since been deleted (although the comments remain), but the gist was that someone in WSB had this theory that, since GameStop was so highly shorted, they could all start buying up shares and put on a squeeze. It was well-coordinated, with real sophistication masked by tendies, diamond hands, and rocket emojis.

I was already working on my essay for last Monday, so I brushed it off and didn’t write about GameStop before anyone else because, remember, I am an idiot. Then on Friday, it started happening:

The story became the story by Monday, when $GME broke $100 and the Wall Street Journal reported that Citadel and Steve Cohen’s Point72 were injecting $2.75 billion into Melvin Capital, the fund with the most short exposure to GameStop, to save it from insolvency.

Remember Citadel from earlier? They’re the ones that Robinhood sells its order flow to, and maybe the biggest winner in this story. One of the largest, most sophisticated hedge funds in the world made out pretty well for a situation in which the little guys stuck it to the hedge funds:

Citadel generated a record $6.7 billion in revenue in 2020 on increased volatility.

It scooped up $2 billion worth of revenue shares in Melvin on the cheap.

The WSJ reported that 29% of all $GME trading last week went through Citadel, which means it was likely able to make a ton of money on the spread.

This, too, is not evil. It’s just the way the game is played, and Citadel played brilliantly.

It’s also the first crack in the narrative that retail traders are the big winners here and the hedge funds are feeling the pain. Sure, funds like Melvin that were short $GME are hurting, but generally, Wall Street banks and hedge funds profit from and adore volatility. And last week was volatile as hell, with the VIX, an index that tracks volatility, spiking 69% (nice) from $21.91 on Friday to $37.21 on Wednesday.

On Thursday, without explanation, Robinhood halted trading in GameStop, AMC, Nokia, and ten other companies in WSB’s crosshairs. Halting trading stopped the momentum that was building in those companies, gave short funds a chance to get out, and cost Robinhood users money.

People were PISSED. Democrats, Republicans, Chamath, Dave Portnoy, AOC, Ted Cruz. Everyone agreed. Robinhood was bad.

Conspiracy theories abounded: Robinhood was protecting its real clients, the hedge funds. The SEC made Robinhood do it. The Illuminati was somehow involved. Robinhood was about to be insolvent.

On Thursday evening, Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev went on CNBC to try to put out the fire, and totally botched it:

Instead of addressing the issues head-on, Tenev deflected, compared Robinhood to Clorox (too much demand lol!), and touted Robinhood’s #1 App Store ranking. People weren’t impressed.

This morning around 2am est, in a bizarre turn, Elon Musk interviewed Tenev on Clubhouse. His answers were more detailed but equally unsatisfying.

(FWIW, people have pointed out that /u/DeepFuckingValue, the Reddit user behind the $GME trade, looks exactly like Vlad Tenev with a headband, and they have never been seen in the same room...)

Here’s the thing: Robinhood wasn’t the only company that halted trading in those names. The more traditional brokerages did too, as did companies like WeBull and Public that clear trades through Apex. There were legitimate reasons for Robinhood to halt trading in $GME and the twelve other stocks, relating to the way that trades are cleared. This thread is the best explanation I’ve found of the whole thing:

It’s detailed and technical and you should read the whole thing if you want to really understand how it works, but the main takeaway is: by enabling so many people to trade on margin, Robinhood got hit with a margin call of its own. Robinhood Robinhooded Robinhood.

It handled the margin call in two ways:

Raised Cash. Robinhood raised $1 billion from existing investors and drew on a $500 million line of credit in order to put up cash to meet liquidity requirements.

Halted Trading in Those 13 Stocks. To stop the risk from getting more out of hand, Robinhood (and other brokerages) blocked users from trading them.

These were maybe the only moves that Robinhood could have made given the situation. Robinhood wasn’t protecting Citadel (Citadel was doing just fine!), Robinhood was protecting Robinhood.

But even after the conspiracy theories were largely disproved, people were still mad at Robinhood. Chamath tweeted that he passed on Robinhood three times “because integrity compounds and assholes will fuck you” (he is SPAC’ing a competitor, SoFi). And an enterprising Redditor took out an airplane banner that read, simply, “Suck my nuts Robinhood.”

Here’s why I think the wrath persisted: Robinhood encouraged reckless trading among its users with no regards for the consequences for years, all while saying the company was on their side. If a Robinhood trader gets blown up by margin, they’re wiped out. “Too bad, you’re an adult.” But when Robinhood was about to get wiped out by margin itself, it halted trading to protect itself at the expense of the users who held the stock. And it didn’t have the courage to address the situation head on. After claiming that it wanted to democratize trading, and that retail traders should have all the same rights as the institutional guys, it treated its users like idiots as soon as the going got tough.

It created chaos, and then pushed the consequences onto its users. It reaped, users sowed.

The company isn’t evil. It optimized for growth, and it was succeeding. But this whole experience exposed the company for what it is, and lost the us vs. them mystique that was the main thing driving its growth.

So what happens next?

Where Do We Go From Here?

I don’t think Robinhood is going to shut down tomorrow. Some smart people actually think this is a net positive for the company.

The “This is Fine” argument goes something like this: “No press is bad press.” Trading seems fun, if those guys are getting rich, I want to join in, and Robinhood seems like an easy way to do it.

They might have a point. Robinhood is currently the #1 app in the App Store. It was downloaded 177,000 times on Thursday alone according to Apptopia.

The other argument here is that Robinhood has nearly unlimited access to investors who want to give it money. To whit, Sheel Mohnot, the guy from the tweet above, received an email from someone raising a fund to buy Robinhood secondary (which doesn’t actually give the company liquidity but speaks to market appetite) at a $30.3 billion valuation, up 171% since September!

Short-term, I think that’s right. Longer term, I’m not so sure. What makes Robinhood Robinhood is the company’s willingness to sow chaos to grow. Limit that, and the company is a lot less exciting to users and investors. And when users want to leave, there’s not much stopping them: the company didn’t have any real moats beyond counter-positioning and brand, both of which it tarnished in this process.

So what happens to Robinhood long-term?

There are a couple comps to look at: Uber and Napster.

Uber. Uber grew more impressively than any atoms-based company in history by skirting regulations and relying on adoring customers to back them up. It worked for years. The company was on the verge of crushing, and potentially acquiring, Lyft when, in January 2017, the #DeleteUber movement struck. It lost its important customer love, gave its hobbling competitor a new life, and limped into the public markets in 2019 without the winner-take-all unit economics it was on the path to achieving.

It struggled out of the gate as investors worried about its unit economics, but despite a pandemic that slowed down rides, the company is improving and its stock has bounced back. It’s now trading 22% above its IPO price.

There are a couple of key differences between Uber and Robinhood:

Honesty. Uber has always been comfortable in its role as the growth-at-all-costs bad boy of Silicon Valley. #DeleteUber was a hit to the company’s reputation, and competitive advantage, but it didn’t shake the core of what made Uber Uber.

Moats. Uber has honest-to-goodness network effects and moats. It’s the leader in its space, and the product benefits as more riders and drivers use it.

Importance of Product. Uber handles peoples’ commutes; Robinhood handles their money.

How about Napster?

Napster

In Entropy Theory, I wrote about the story of Napster:

Napster increased the entropy of the music industry (creating entropy) and was shut down in 2001 under legal pressure. The music industry (victimized by entropy), wielding lawsuits in an attempt to go back to the way things were, fared no better. Whether via Napster, Limewire, or any other number of online music file sharing services, the genie was out of the bottle and the entropy had increased: people wanted to listen to what they wanted, when they wanted, online.

You know how this story ends. The old way of doing things (CDs, pay-per-album) lost, but so too did the new chaotic force, Napster. A federal judge in San Francisco shut it down, saying that the company encourages “wholesale infringement.” Spotify came in, wrangled the entropy that Napster created, and built what is now a nearly $60 billion business.

So is Robinhood Uber or Napster?

Robinhood will be fine in the short-term. There’s enough money floating around looking for growth that it should be able to remain solvent, and trading right now is incredibly fun.

But I am very skeptical about Robinhood’s long-term prospects for a few reasons.

The Genie is Out of the Bottle. Entropy constantly increases. Anyone who thought 2020 would be the wildest year they’ve ever lived through must be surprised at how January 2021 is going. This current environment is not an anomaly, but part of an unbreakable trend towards increasing entropy. If WallStreetBets is shut down, something else will pop up in its place. If Robinhood survives this liquidity crisis, there will be another, then another, then another. It will either have to add friction to its product, when frictionlessness is the main thing it has going for it, or get run over. Unless the regulators step in…

Increased Regulation. …in which case, Robinhood is going to face regulatory pressure. The SEC has already said that it will “closely review actions taken by regulated entities that may disadvantage investors or otherwise unduly inhibit their ability to trade certain securities.” The company has already run afoul of regulators, and its ability to stay jusssssst inside the lines will be threatened. Plus, under a Biden administration that is all about unity, contempt for Robinhood is the one thing that has actually unified the country. While Robinhood was viewed as a democratizing force and loved by users, it was protected. Now, there are a lot of people who would be happy to see it punished. But I’m not a lawyer or a politician; I just write a business newsletter. So for me, the biggest issue is…

No Moats and Anti-Goldilocks Product. Robinhood has no moats. Until this past week, its brand was a moat. And it counter-positioned against the incumbents well. And its UX is the smoothest in the game. But the brand took a huge hit last week, incumbents have actually matched it on zero commission trading, and last week exposed the dangers of a too-smooth trading UX. If you squint, the company may have scale economies or a cornered resource based on the fact that it built its own trading infrastructure and clearing tech, but the app crashes during high volume, volatile periods, the worst time for it to crash, and too many people trading the same stocks means potential margin calls and trading halts.

Worse, it doesn’t serve any set of users perfectly well. It’s the anti-Goldilocks.

For new investors, the real unsophisticated ones, the product has too few guardrails. It’s too easy to trade options and too easy to take on crushing amounts of margin. That works when the market is hot and trading is fun, but it’s going to be disastrous when the market turns. It’s not mean or patronizing to say this: some people are unsophisticated traders, just like I’m an unsophisticated doctor or lawyer or car mechanic, and they should probably be using an app in which it’s not so easy to lose everything.

But even though we’re all idiots, some retail traders are genuinely sophisticated. Even hedge fund managers are retail traders in their personal accounts, and WallStreetBets has proven that there are stock market geniuses hidden in the unlikeliest of places. Robinhood isn’t powerful enough for those sophisticated retail investors.

On Friday, the WSJ ran an interview with the guy behind all of this, the Redditor called /u/DeepFuckingValue, who, it turns out, is an ex-Mass Mutual marketer named Keith Gill. Right at the top, they ran a picture of the genius retail trader and WSB cult hero:

He’s not on an app. He’s on a “typical computer setup with multiple monitors,” the same kind that Robinhood wanted to free us from in the first place.

There are sophisticated retail traders everywhere. Robinhood isn’t for them, either.

Ultimately, Robinhood’s fate is tied to the roaring market of which it is both a symptom, and to a lesser extent, a cause.

If things turn south any time soon, its users will lose painful amounts of money, growth stage investors will wonder if it’s worth continuing to pour money into an undifferentiated product with no real moats at a $30 billion valuation, and it could get hit with a crippling margin call the next time something like GameStop happens. Maybe even today, during #silversqueeze.

That will open the door for new financial products that wrangle the entropy Robinhood created.

If st0nks continue to only go up, though, a lot of retail traders will make a lot of money on Robinhood, a lot of investors will be willing to pour money into the company itself, it could IPO, and it might have time to wrangle the entropy itself. Tendies for everyone.

Thanks to Dan for editing!

One more thing: WeWork might SPAC! Dror Poleg and I talked about the company on Friday:

Good luck out there this week! See you on Thursday.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Out of the hundreds and hundreds of notes published on this topic, this is the best I've seen by far. Nice work.

Another great piece, Packy!

Just a question about frontrunning. You say that Citadel the hedge fund is the same that Robinhood sells its order flow to. But aren’t Citadel & Citadel Securities ‘just’ sister companies and isn’t there regulation to prevent insider information sharing between them? Also front running would actually be illegal? They’re ‘just’ making money on the spread, right?

Don’t mean to imply anything here - I’m new to this topic and trying to wrap my head around it.