Prescription Drug Commercials: Why Are You the Way You Are?

A Not Boring Out-of-Pocket Guest Post

Welcome to the 1,912 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Thursday! Join 48,356 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by … Secureframe

Secureframe helps companies get enterprise ready by streamlining SOC 2 and ISO 27001 compliance. Secureframe allows companies to get compliant within weeks, rather than months and monitors 40+ services, including AWS, GCP, and Azure.

Whether you’re an enterprise or a small startup, if you want to sell into enterprises, you’re going to need to be compliant. Secureframe makes the process faster and easier, saving their customers an average of 50% on audit costs and hundreds of hours of time.

Secureframe’s team of compliance experts and auditors are happy to help answer any questions and give you an overview of SOC 2 or ISO 27001, even if you don't need it today. Schedule a demo and learn how:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday!

There are a lot of things that confuse me, but maybe none more than prescription drug commercials. People eating ice cream while a voiceover talks about herpes. The Cialis couple in the bathtubs in a field (backstory revealed below). The long list of side effects that seem much worse than whatever disease the advertised drug claims to cure.

I’ve been curious about why prescription drug commercials are the way they are forever; challenge was, I don’t know very much about healthcare. I haven’t been to the doctor in years. I’m not the guy to solve this mystery. But I know the guy.

Nikhil Krishnan’s twitter profile says it all: “Thinkboi. Making healthcare understandable through memes, shitposts, and novelty products.” He writes the funniest healthcare newsletter out there, approachable for newbies (like me) and deep enough to be valuable to industry professionals. You should subscribe:

He’s the perfect guy to explain something as simultaneously ludicrous and technical as prescription drug commercials. Mystery solved.

Let’s get to it.

Prescription Drug Commercials

As the Meghan/Harry + Oprah interview aired in March, Americans were shocked. How could the British Royal Family treat them that way?

Meanwhile, people in the UK watching the interview were also shocked. At the fact that pharmaceutical companies were advertising during the interview.

There are only two countries in the world that allow for direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: the US and New Zealand. The only other thing these two countries share are people buying a lot of property in New Zealand.

But why exactly do pharmaceutical companies advertise to us? Does it work or affect care? What’s the deal with the million side effects they list at the end?

I’m here to talk to you about the world of pharma marketing and how it works. But I actually want to get into how pharma marketing is evolving with technology, look at whether consumer advertising is definitively bad, and suggest that we should actually be focusing our scrutiny on physician marketing.

Why Do Pharma Companies Market to Consumers?

The first question is an obvious one. It’s the one the Brits had. Why do pharma companies market to the consumers when the consumers need to go to the doctor, and the doctor’s going to decide anyway?

Pharma advertising has largely two main goals.

First is for undiagnosed patients. Increasing general awareness about a disease is going to make you more likely to see a doctor in the first place, which increases the chance of you getting the drug prescribed. For example if you hear a commercial that says, “If you suffer from insomnia, hot sweats, or are having nightmares that you have no idea where your social security card is,” you might suddenly realize that you have those issues and there might be something to fix them. You’ll especially see that for disease areas which are lifestyle hampering or easily self-diagnosed (sexual issues, skin and hair issues, pain, mental health, sleep issues, weight issues, stomach problems, and more). Below is some data on advertising spend by disease area.

Fun fact, Claritin was really one of the first significant direct-to-consumer pharma campaigns with their “blue skies” campaign in the mid 1990s. Now allergy meds are all over-the-counter, so the spend has dropped like crazy.

For already diagnosed patients, these ads are helpful for patients who are especially active in looking for different treatments for their diseases. This happens a lot in diseases for which there’s high variance in physician recommendations. Areas like cancer or rare diseases want to arm you with information about a drug so you actually ask your doctor if the drug might make sense for your cancer type. As personalized advertising gets more targeted and the therapies themselves target smaller and smaller patient segments, ads for these drugs become a better investment. They have exploded accordingly.

What Are the Rules Around Marketing to Consumers?

As you can imagine, pharma marketing is murky and there are tons and tons of rules around what you can and can’t do. But I thought I’d just go into a few.

Rule 1: The product name has to be memorable for consumers but cannot be even close to confused with any drug that’s already on the market.

Quick game, which of these is a drug name and which are Lord of the Ring Characters? Galadriel, Horizant, Zestril, Elendil, Denethor, Afinitor. Be honest, you got less than 50% right.

Drug companies want you to remember the name (feat Fort Minor) but also will 100% get sued for trademark issues by other drug companies if you even slightly seem to be riding the coattails of their brand success. Plus, the FDA obviously doesn’t want consumers to get two drugs confused; taking the wrong one can cause serious health issues. That’s why you have these very strange sounding, un-Googlable drug names, advertised directly to consumers.

Rule 2: The advertisements need to say the name of the drug (brand and generic), at least one FDA-approved use for the drug, and the most significant risks of the drug.

While there are some nuanced differences between print, television, radio, etc. the general gist is that drug manufacturers need to give a “fair and balanced” view of the drug. That means including the major side effects.

This is usually the most jarring part of pharma advertising. When an ad airs, it sounds like the drug is just as likely to kill you as it is to help you, and the side effect listing will happen over some lovely couple running through a field of tulips or whatever so it doesn’t actually seem that bad. Non-US residents can see an example here.

Rule 3: There are different rules between “product claim” advertisements, “reminder” advertisements, and “help seeking” ads.

I was on the subway the other day and I saw what I thought was possibly the worst advertisement I’ve ever seen. Oh you wanna know what this product is? F*** you.

This is an example of a “reminder” advertisement. It’s not actually making any claims about what the product does. It’s just reminding people who might already know about the product that it does in fact exist. Really high-risk products will still have to include a “boxed warning” on these ads. These are different from the “product claim” advertisements I’ve been talking about where the drug actually says what it treats and how well it works.

So those are two types of pharma ads, but to make it even more confusing there’s a third called “help seeking” ads. These are ads that actually aren’t about a product at all, they’re just talking about symptoms of a condition generally and HAPPEN to have the logo of a drug company on it without talking about the drug itself, and will say things vaguely like, “There is help, ask your doctor today.” These kinds of ads actually fall under the FTC instead of the FDA.

Pharma Marketing is Evolving

Like every part of healthcare, eVeRyThinG ChAngEd WiTH TeCh. Here are some examples.

Ads shifting to the point-of-care: Every ecommerce native company salivates at the thought of getting an ad as close to the checkout cart as possible. Pharma is no different. Wouldn’t it be great if they could advertise to you right when you’re about to talk to your doctor? Outcome Health installs TVs in physicians offices to display ads, Phreesia has sponsored content during the check-in process at a doctor’s visit and sends follow up messaging, and Semcasting would use Wi-Fi in physician offices to serve up information about pharma products. Even virtual waiting rooms for telemedicine are getting ads, in case you missed the experience of sadly sitting at a doctor’s office and reading the pamphlets.

Pharma site telemedicine plug-ins: One shift is to bring ads to the point of care, but another is to bring the point-of-care to pharma itself. This happens by adding buttons on the drug brand website that can link you out to a telemedicine consultation in one touch. A person looking at a drug’s website is pretty high intent, so the telemedicine buttons make it easy for you to connect with a doctor to get a prescription written if you want. The physicians are usually part of a separate company unaffiliated with the pharma company, but if you came from the website you’re probably going to request that brand of drug during the visit.

Shifting the marketing to D2C pharmacies: Why do the marketing yourself if you can work with a company that specializes in it? Companies like Ro are partnering with the generic divisions of pharma companies like Greenstone to supply medications to patients exclusively. Thirty Madisonpartnered with Biohaven to create the Cove brand for their migraine drug, Nurtec. The pharmacies build up the branding, spend on marketing, and acquire customers while the pharma company gets the distribution for their drug.

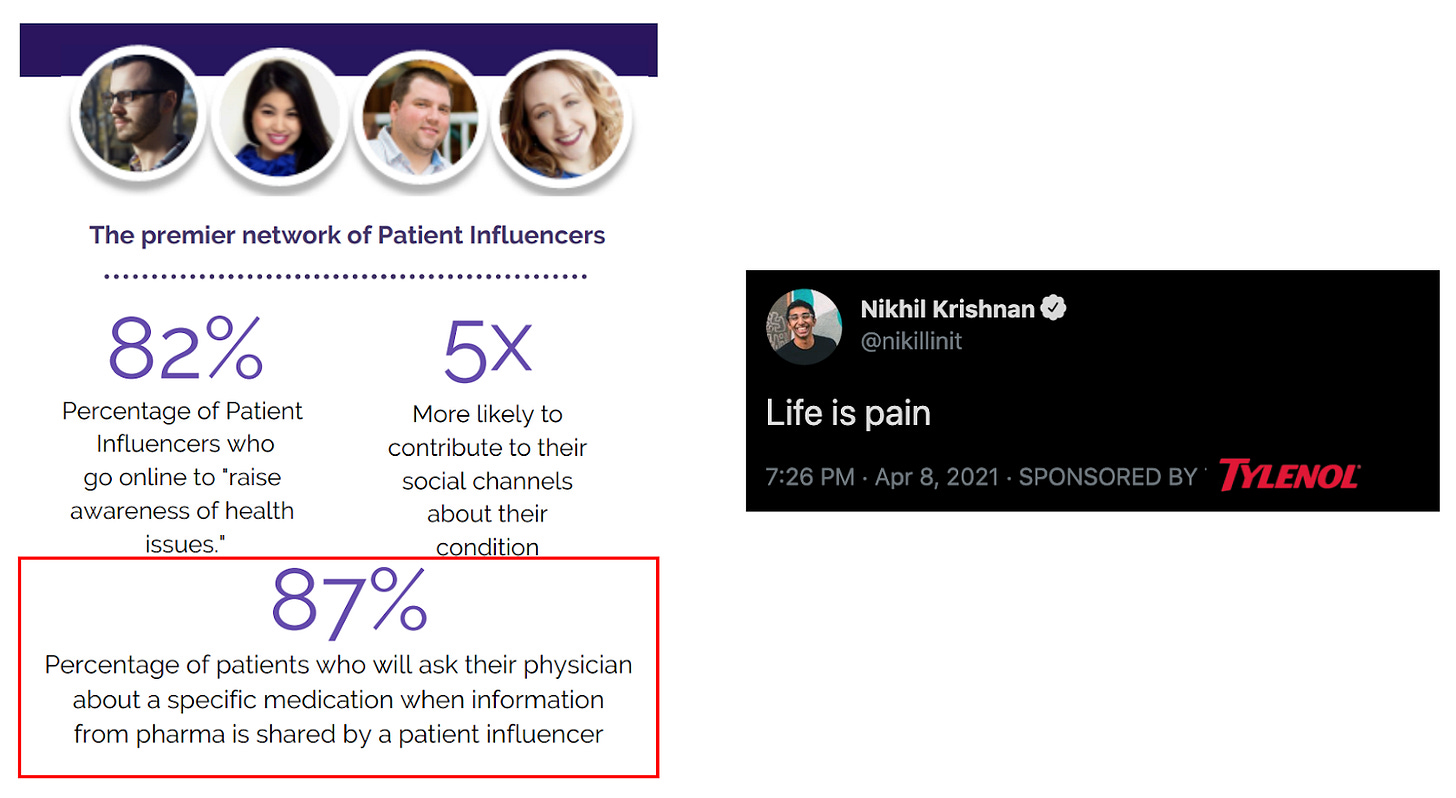

Patient influencers: Along with the rise of social media, influencers in different disease areas have risen to fame. They’ll typically talk about living with their disease and attract followers that tend to have the disease as well who are looking for tips and a community. Even everyday influencers like the Kardashians are getting in on the pharma action, with the FDA being less than pleased. These influencers are becoming ad channels for pharma companies, with companies like WeGo Health connecting pharma companies to the different influencers.

Memes: I cannot believe this, but pharma companies themselves have now discovered advertising with memes. Below are some examples I’ve seen. Imagine asking the compliance department if you can fire these off lmao. The Nurtec one isn’t even using the meme correctly! What’s doubly funny about this is that they’re still still trying to include the side effect profiles so they comply with the “fair and balanced” view, but as you can imagine, it’s super difficult to do that in 280 characters or an Instagram square format.

So... Is Marketing to Consumers Bad?

The popular stance to take is “pharma marketing bad”, and it’s frankly not super hard to argue. Why should pharma companies be spending money to induce consumer demand when they could instead take that money and reinvest it into R&D?

Just for fun and my love of angry emails, I’ll play a little devil’s advocate.

One question is whether these ads are a net negative societal cost. This means that the dollar cost going into these ads (and the value of where they could be otherwise invested) is higher than the benefits they provide.

Here’s a paper that found prescriptions for statins, a very important cholesterol lowering drug, dropped when there were less statin ads due to the 2008 political campaign taking up all the ad space. And we want relevant people to take statins; it’s bad if they don’t! Another paper argues that a 10% increase in antidepressants ad spend demonstrated an 0.3% increase in antidepressant prescriptions followed by a decrease in workplace absenteeism (they estimate worth $770M).

This is a very hard area to study but in general you can probably argue there are some beneficial effects of ads to get people to take useful drugs. On the flipside, a dollar invested into pharma R&D has gotten steadily much worse over time, dropping to 1.8% return on a dollar invested.

So, is it possible that pharma ad investment might have a higher societal benefit than we think? I’m not going to say definitively yes, but I don’t think it’s as black and white as people say.

Another question is whether pharma marketing is misleading patients or disrupting the physician visit where the prescription decision is made. The FDA themselves actually ran a survey in 2002 to understand this.

73% of physicians indicated that their patient in this encounter asked thoughtful questions because of the direct-to-consumer ad exposure.

91% of physicians reported that the particular patient they recalled did not attempt to influence their treatment in a manner that would have been harmful to the patient

58% of physicians thought direct-to-consumer ads made patients more involved in their health (“somewhat” + “a great deal”).

On the flip side, 65% believe the ads confuse patients about the relative risks and benefits of prescription drugs and 22% of primary care physicians felt “somewhat” or “very” pressured to write a prescription.

So I think there are pros and cons that are more reflective of healthcare in America as a whole, where our ethos is to give patients as much information as possible. This inevitably leads to some tensions with physicians. This is not dissimilar to the tensions that exist with physicians and patients Googling their symptoms before they come for a visit. Not saying either way is right, it’s just an ideological difference on whether we want consumers armed with information when talking to their doctor (even if their information might be biased).

The final point I’ll argue is that at least we KNOW when we’re being advertised to if we see a TV commercial. Patients are pretty clear about the motivation of the company doing the advertising. However, in 2016, $20.3B was invested into advertising to physicians. That’s more than 2x the spend going directly to consumers. I would argue this is actually much worse, because consumers are less privy to the fact that their physicians are ALSO influenced by drug company marketing. A disproportionate amount of the conversation focuses on the direct-to-consumer advertising aspect, when physician marketing is more problematic (though tackling one doesn’t mean we can’t also be addressing the other).

In Part 2 of this series I’ll talk about the more opaque world of pharma marketing to physicians and how that’s also changing as well. Sign up for Out-Of-Pocket to get it.

Just to reiterate: I’m not some sort of pharma shill lol, but just wanted to surface some of the less common viewpoints on this issue. And hopefully you learned a bit more about why some of the ads you see are the way they are.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka “pharma I’ll help you with your memes, call me”

P.S. Everyone definitely remembers that Cialis commercial with two people sitting side-by-side in bathtubs. Turns out that was a decision made last minute on set and I guess they just had two bathtubs laying around??? Now they just roll with it because it’s so iconic.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Monday,

Packy