Welcome to the 986 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Thursday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 46,119 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Thursday! We’re bringing back one of my favorite formats: the Not Boring Guest Post. And we’re doing it with the most prolific Not Boring Guest Poster of All Time (NBGPAT), Ali Montag.

These Guest Posts are all about getting perspectives and insights that are different from mine. Ali is a perfect counterbalance to me, because she understands tech and has worked at startups, but adds a Texas-sized dose of, “Woah, slow down, there is life beyond tech and between the coasts. Kick back, relax, and enjoy some lasagna.”

Over the past year, Ali has graced your inboxes with essays on Kim and Kanye, JoJo Siwa, and Chip and Joanna Gaines. Today, Ali is back with a piece on the Creator GOAT.

When she’s not writing herself, Ali runs a community for writers called Newsletter Crew, which, of course, has a newsletter on writing and writers. You should subscribe.

Let’s get to it.

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by… UserLeap

If you’ve been reading Not Boring to the bottom, 1. Thank you! 2. You probably noticed the microsurvey I’ve been running to help me make Not Boring better. I built it with UserLeap.

UserLeap is a continuous research platform that makes it easy to build and embed microsurveys into your product to learn about your customers in real-time. Product teams use UserLeap to gather qualitative insights as easily as they get quantitative ones, and automatically categorizes insights so teams can take quick action.

UserLeap is addictive. I check it at least once a day. I love reading what you write, even when it hurts. People and startups can use UserLeap for free, like I do, by signing up here.

Teams at Opendoor, Loom, and Dropbox love UserLeap too. The UserLeap team knows that once teams start using it, they don’t stop, so it’s offering a free onboarding and 30-day trial to any enterprise company (~100,000+ users). Sign up below to reserve your free trial.

Martha Stewart’s Reign of Relevancy

A few weeks ago, my mom handed me an envelope from Martha Stewart Living Magazine.

“It’s on sale,” she said. “I thought you might want it.”

I opened the envelope. It held an offer for a one-year magazine subscription, in print and online, discounted from $49.90 to $10. Tucked with the paper, Martha sent a few gifts: A pocket sized calendar, a recipe for chocolate frosting, a sewing template for “tight, uniform stitching,” and a “Stain Removal Guide,” covering the removal of wax, gum, chocolate, vinaigrette, ball-point ink, and felt-tip ink from delicate fabrics.

I thought: Is Martha Stewart still in business?

Yes. She is. At 79 years old, Martha Stewart launched a CBD gummy brand. She published her 97th book. She debuted a new HGTV show. Her flagship magazine Martha Stewart Living, owned by Meredith Corporation, touted 12 million digital readers and 7 million print subscribers in 2020. Her audience is still buying what she’s selling.

Her brand—perhaps the most famous linear commerce business centered on a single individual—is the original blueprint for Substack writers and TikTok teens today.

“Media leads,” Stewart says. “[I] started writing books first, then a magazine, then television and radio, then product. Media leads and merchandise follows. You build up an interest, a curiosity in your readership and a desire for things, and the merchandise follows.”

But this is not an essay about the creator economy. You can read 15 great Substacks about the business of creators. This is not one of those.

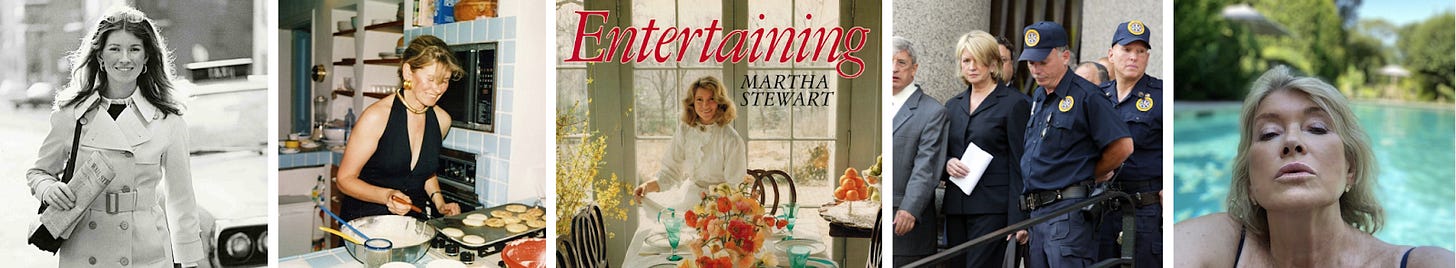

This is a look at a more delicate ingredient in the linear commerce recipe: Relevancy. Martha Stewart has, over the course of a 50-year career, with mystically perfect timing, refashioned herself from Wall Street stock broker to Connecticut catering chef, from the U.S.’s first self-made woman billionaire to a yoga-teaching inmate in federal prison, from a scandal-tainted villain to renewed brand icon, and from the picture of propriety to Instagram’s latest thirst trap.

What explains the unending appeal of Martha Stewart? How is it that no matter what decade we’re in, she still feels relevant? That’s Stewart’s greatest skill: An uncanny ability to do the opposite of what’s expected—just before everyone else does it. It’s also a framework anyone can use.

Let’s dive in.

Appetizers & Hors d'oeuvres

In 1982, Martha Stewart published her first book, “Entertaining.”

She was 41 years old, the mother of a 17 year old daughter, and in her sixth year of operating a catering company in Westport, Connecticut. Before catering, Stewart spent several years as a stock broker at Monness, Williams and Sidel, on Wall Street. Stewart started the catering business in 1976 with a partner, Norma Collier. But the pair split in less than a year.

“I was happy doing parties for 10 or 12,” Collier told New York Magazine in 1991. “If it wasn’t 1,000 it wasn’t good enough for Martha.”

It was at one of these parties, hosted by Stewart’s then husband Andy Stewart, a publishing executive, that Martha met Alan Mirken, the president of Crown Publishing. Mirken was “so entranced” by the catering (according to Martha) that he asked her to write a book on the spot.

But it was soon Mirken opposite Martha’s ambition: “When the Crown staff added up what it would cost to produce Entertaining, the lavish book that she proposed, they balked,” according to New York Magazine. It was a 10 chapter, +300 page book. It was expensive. It included recipes for hors d'oeuvres like cherry tomatoes stuffed with sour cream and red caviar, but it also included sermons on the “reason, type, and time” to host a party. There were four pages on table dressings alone. (If you were curious, “A ruffled pillow sham is a charming table cover for breakfast.”) Nearly every page had big, glossy photography.

Mirken wanted to cut costs. He suggested cutting the book in half. Martha said no. Crown suggested printing the book in black and white instead of color. Martha said no. Crown proposed printing 20,000 copies. Martha told them to double that.

“I didn’t not expect it to be a hit; that was the funny thing,” Martha said in 1991. “I think that sort of bothered people.”

Lo and behold, it was a hit: It sold out immediately. In the decade that followed, Entertaining sold over 500,000 copies. But more importantly, with the book’s success, Martha found herself at the helm of a newly minted media business.

“I became an expert overnight,” she explains. “That’s what a book does.”

And she kept going. Just a year after writing her first book, Martha published Martha Stewart's Quick Cook (with 200 recipes) in 1983, Martha Stewart's Hors D'Oeuvres (with 150 recipes) in 1984, Martha Stewart's Pies & Tarts (with 100 recipes) in 1985, Weddings in 1987, The Wedding Planner in 1988, and Martha Stewart’s Christmas in 1989. The list goes on.

“I was prolific,” Martha says. “I could write a book a year, to great advantage. I kept writing, and writing, and writing, gradually becoming well known.”

Like any good creator, she also diversified her business.

In 1987, Stewart signed a five-year consulting agreement with K-Mart, earning a million dollars a year to consult on new designs and promote products. She taught classes: 35 people at a time would visit her home in Connecticut for $900 per person, coming to look and learn. In 1990, she gave 30 lectures for $10,000 each, according to New York Magazine.

“I used to do catering,” Martha told David Letterman. “Now I do consulting.”

Next came the magazine. In 1990, Martha Stewart and Time Publishing Ventures launched Martha Stewart Living as a quarterly magazine. Then, in 1992, Martha Stewart Living TV launched as a weekly half-hour syndicated show. The massive distribution of cable TV did what cable TV does: The flywheel became unstoppable.

But why?

Martha wasn’t the only person writing books in the 1980s. She wasn’t the only person making TV in the 1990s. What made her uniquely relevant? What did she see before anyone else?

It’s important to consider the context. Martha Stewart graduated college from Barnard in 1963. At that time, the labor force was changing. “The civil rights movement, legislation promoting equal opportunity in employment, and the women’s rights movement created an atmosphere that was hospitable to more women working outside the home,” according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor.

Things were changing for women. In 1965, married and a mother, Martha was no longer interested in posing for swimsuit catalogs, as she had in the 1950s. It was a new era. She was interested in business. Stewart strode out the apartment door and went to work on Wall Street.

“I loved it,” Stewart said of her years as a stockbroker. “It was very aggressive, and the money you made was amazing. I was making about $135,000, which was a lot.” (That’s $1.1 million today)

Stewart was early to the professional class of women in 1965. But by 1970, things exploded: “Between 1970 and 1980, the labor force participation rates of women in the 25–34 and 35–44 age groups increased by 20.5 percentage points and 14.4 percentage points, respectively. No other labor force group has ever experienced an increase in participation rates of this magnitude in one decade,” according to the BLS.

It was a tectonic shift in the labor force. It was also a tectonic shift in American culture. Working women became mainstream, no longer fringe radicals burning bras. What did that mean? The economic implications of the 1980s became the cultural implications of the 1990s: Sex, marriage, dating, kids. Decades of draconian tradition, gone. The guard rails were off. The rules of the game were suddenly very unclear.

“It was a time when we were supposed to be newly empowered,” writes the New York Times’ Taffy Brodesser-Akner. “We were ’90s women. The battles had been fought; we owned property and voted. We worked and talked endlessly about things like balance. The women’s magazines encouraged us to take initiative, to ask the guy out. We were on the pill. Colleges were giving out condoms, not just to the men but to the women. There were so many mixed messages, and the women I knew were at war to maintain their independence but also still traditional enough to think about the families they’d been engineered to want.”

In the late 1970s, after leaving Wall Street for the Connecticut countryside, Martha must have felt the ground shifting. In those years, while renovating her farmhouse, tilling the ground for vegetables, raising her daughter, growing her catering business, applying the same ferocity to her fruitcakes as she did her bond trades, Martha’s ambition never waned. But a question arose: In all this ambition, who was being left behind?

What about the women who still had to pack school lunches? What about the women responsible for cooking Christmas dinner? What about Martha’s neighbors, the other mothers at school?

Was anyone paying attention to them? Didn’t they have ambition too?

The job of full-time, professional homemaker “was floundering,” Martha said in an interview with Charlie Rose. “We all wanted to escape it, to get out of the house, get that high-paying job and pay somebody else to do everything that we didn’t think was really worthy of our attention. And all of a sudden I realized: it was terribly worthy of our attention.”

Here’s some context from Nora Ephron. “Lots of women didn’t feel like entering into the workforce (or even sharing the raising of children with their husbands), but they felt guilty about this, so they were compelled to elevate full-time parenthood to a sacrament.”

A sacrament. That passion, that need to prove value, to prove the worth of something underestimated by the broader market, is exactly what Martha spotted. She identified not just the trend, but the countertrend.

Mark Penn, the author of “Countertrends Squared,” defines the concept this way: “For every trend, there is a countertrend. It is human nature in the Information Age: every move or desire in one direction seems to inspire a countermovement by another group in the opposite direction.”

As information and choice proliferated, American culture began to no longer move in one direction at a time, but two. In the 1980s and 1990s, professional women were becoming an increasingly powerful, important demographic. But in equal and opposite measure, homemakers were important too. They had hopes. They had dreams. They had ambitions. And no one was paying attention.

“It was about filling a void,” Stewart said. “Every time I wrote a book, it was to fill a void that I and my friends had to have filled. When I wrote a book about hors d'oeuvres it was because there wasn’t a great book about hors d'oeuvres.”

How many categories—the hors d'oeuvres of 2021—are we overlooking today by following the trends, but not their counters?

Unpacking Countertrends

We live in a world of diametrically opposed forces: The U.S. isn’t just more conservative, it’s more conservative and more liberal. The wedding industry is bigger than ever, and at the same time, more Americans than ever question the institution of marriage. “One group seeks more technology, another wants to sit in the Amtrak Quiet Car,” Penn writes. “Some can’t sit through a six-second commercial; others spend hours and hours binge-watching TV.”

Taking the inverse of existing trends can be fertile ground for finding underserved audiences.

Put another way by Sari Azout: “The opposite of a good idea can be a good idea.”

“For example, there are two great ways of welcoming people to a hotel,” Azout writes. “One of them is highly automated and impersonal, the other is highly elaborate and involves large degrees of obsequiousness. There are two ways to win in e-commerce. You can give people infinite choice (Amazon) or you can reduce the burden of choice.”

But it’s not as obvious as you may think. One of the best examples I see of countertrend positioning today—following precisely in Martha Stewart’s footsteps—is Simon Sarris.

Sarris, a software engineer, is also a renaissance man. He makes fires. He bakes bread. He spends time quietly writing and reading about philosophy, brewing coffee, taking walks through the snow with his wife and child. He does not live in San Francisco. He does not wear Allbirds. He does not race to answer Slack notifications. Instead, he lives a quiet, calm life, one grounded in commitment and devotion.

It’s directly counter to the Travis-Kalanick-Superpumped-hustle-grind-win-scale-growth-hack tres-comma-club narrative men in tech have been swimming in, wittingly or unwittingly, for the last decade.

“What if you didn’t have to blitzscale to be happy?” Sarris asks with every post.

It’s worth asking why we marvel at his photos. Simon’s life is not that unique: Millions of Americans without Twitter accounts enjoy quiet mornings with their babies every day. They have done this in states like Wisconsin and Iowa and Texas for generations.

Why is a photo by the fire so stirring? Because in a feed full of growth hacks and fundraise announcements, it's not more of the same that is compelling—it’s the inverse.

Therein lays Martha Stewart’s greatest skill: To see both sides of the coin and flip between the two.

Being written off as old and outdated? Get high with Snoop Dogg. Finding yourself the face of misguided anger after becoming the first self-made woman billionaire and falling from grace? Knit a poncho in prison. Being told you’re too frumpy? Post a thirst trap. For Martha, this strategy gave her the rarest value a brand can have: Longevity.

“I have survived the rigors of time, of marriage, of childbearing, of building a business from scratch,” Stewart said in a November interview. “I have survived very nicely, and I think I make the most of it.”

What comes next?

Today, the era of Martha is ending. Things are speeding up. The world is no longer moving in just two directions at a time.

As linear media (cable TV, magazines, books) are replaced by exponential media (TikTok, Twitter, Reddit) trends aren’t bifurcated, they’re moving in every direction—all at once.

Take this analysis of the GameStop phenomenon by Ben Thompson:

There have been a thousand stories about what the GameStop saga has been about: a genuine belief in GameStop, a planned-out short squeeze, populist anger against Wall Street, boredom and quarantine, greed, hedge fund pile-ons, you name it there is an article arguing it. I suspect that most everyone is right, much as the proverbial blind men feeling an elephant are all accurate in their descriptions, even though they are completely different. What seems clear is that the elephant is the Internet.”

No longer are there equal and opposite reactions to GameStop; two different lenses through which to understand the conflict. There are an unlimited number of lenses.

Unlimited choice, proliferated by the Internet, is why “everyone has a story about what happened with GameStop, and why they are all true,” Thompson writes. “The 2019 story was correct, but so was the summer 2020 story, and the fall 2020 story, and the January 2021 story. None of those stories, though, existed in isolation: they built on the stories that came before, duplicating and mutating them along the way.

Think about the most powerful movements this year: GameStop, Bitcoin, $DOGE, Free Britney Spears, QAnon. All decentralized, all vastly open to interpretation, all offering an unlimited number of lenses.

Will there be a time when audiences don’t want to follow a celebrity just for their advice—recipes from Martha Stewart or career plans from Sheryl Sandberg? A time when we ask not for explicit instructions, but for a treasure map?

The Martha Stewart of tomorrow may not look like a single person. It may go even farther than AI influencers like Lil Miquela. It may be a loose collective, a single idea with a million fragments, a trailhead with innumerable paths to wander. It will look less like a cookbook, and more like a choose your own adventure novel.

I often think of this quote by Walter Kirn in Harpers Magazine in an essay on QAnon:

The audience for internet narratives doesn’t want to read, it wants to write. It doesn’t want answers provided, it wants to search for them. It doesn’t want to sit and be amused, it wants to be sent on a mission. It wants to do.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Monday,

Packy

Appreciate this post especially since I had the opportunity to work at Martha's company and interview her about her career path on my careertalk show on her SIRIUSXM channel. I also appreciate the sentiment at the end of the post and it sounds to me like the arrival of "unity consciousness" where each one of us is here to receive information and share information from our unique perspectives. Like individual points of light on a sphere, together we weave together a fuller picture than any of us could do alone. Exciting times!