Lithic's New Customer

Meet the $800M 💳 🚀 Making Issuing Cards as Easy as Accepting Payments

Welcome to the 987 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since Monday! Join 68,700 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring, the whole thing, is brought to you by... Lithic

Lithic is a modern, developer-first, card issuing and processing solution for innovative startups, fintech companies, and brands. They make issuing cards so much easier than you’d expect.

If you want to join an API-first, NYC-based 💳 🚀 with $100 billion ambitions, they’re hiring:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Some companies that just feel like they have it. It’s not just growth, although that’s there too. It’s a combination of a bunch of good things happening all at once.

Lithic is one of those companies.

Lithic, which is really two fintech companies (one B2C, one B2B) under one roof, has announced $110 million in two rounds of venture funding since May. It passed $1 billion in annual processing volume and quadrupled growth on its API platform in the past eight months. It’s on pace to 2-3x again. That’s the growth-y stuff.

Then there’s the less tangible stuff.

Like people. I’ve followed the @regulatorynerd twitter account for a while for his smart takes on fintech from someone who’s been in it, first at Square, then at Stripe. In September, he changed his bio to Privacy.com (it says Lithic now). Or Charlie Kroll, who joined Lithic as CRO after co-founding two fintechs – Ellevest and Andera. And Nikil Konduru, whose measured piece on Banking-as-a-Service Euphoria impressed me last August, when he was a VC at Nyca. He’s at Lithic now, too.

And customer pull. I’ve talked to two Not Boring Capital companies who are signing with Lithic in the past ten days, and my portfolio’s not that big. A third may sign up, too.

Then there’s the je ne sais quoi of everyone just agreeing that the company has it. When Yoni Rechtman at Tusk Ventures reached out in June to ask if I wanted to meet a portfolio founder running a “very cool company with a ton of momentum and a really complex model/backstory,” it was a no-brainer yes. After I met with Lithic founder and CEO Bo Jiang, I got the hype, but I wanted to double-check with Mr. Fintech Today, Ian Kar, to confirm. Green light:

After a few more glowing reviews, we decided to go ahead with a Sponsored Deep Dive, and I asked Bo if Not Boring Capital could invest. So this is my favorite kind of Thursday post: a Sponsored Deep Dive x Investment Memo.

Since I invested, I’ve started bringing Lithic up in conversation with other founders and investors. Universally, the responses are positive, almost like, “Yeah, duh, that’s a great company.” It’s the same vibe I got when I talked about MainStreet or Ramp a year ago.

Yoni was right: Lithic has a ton of momentum and just the right amount of complexity for a compelling Not Boring piece.

Let’s get to it.

Lithic’s New Customer

I’ve been on a bit of a tech essay classics spree recently. There are fundamental concepts about which others have written beautifully that we should all understand if we want to grok what’s going on in the world.

Last week, I dove into two of Tim Urban’s on exponential growth. On Monday, I went deep on Eugene Wei’s Status-as-a-Service. And today, we’re turning to the King: Ben Thompson.

Thompson has written so many of my favorite pieces in Stratechery. My very first piece when I started writing was about some of my favorites. And right there in my five favorite BT posts and podcasts is one called Amazon’s New Customer (and the follow-up podcast, Valuing Value Chains).

I remember when I first heard that Amazon was buying Whole Foods in 2017. I was on the golf course, and I don’t golf (it was for a friend’s wedding), so it was particularly memorable. I remember that grocery stocks tanked, and that none of us were really sure what Amazon was doing. Ben Thompson did though.

A year earlier, Thompson had written The Amazon Tax, detailing Amazon’s overarching strategy across e-commerce (Amazon.com) and enterprise (AWS). When Amazon bought Whole Foods, he was ready. He called that they were running the same playbook that they’d run with e-commerce, enterprise, and even logistics.

I loved that piece because it distilled so much complexity down into an easy-to-understand framework… which we will get to in a little bit.

I bring that up because Lithic made an Amazonian move recently. If you haven’t heard about the company, that’s OK. It just became Lithic. Before that, it was Privacy.com.

Privacy.com issues single-use virtual cards to people who want to keep their payment information safe as they buy things across the internet. If hackers breach a site you’ve bought something from and steal all of the credit card information, that’s fine. The Privacy.com card you used there already self-destructed after that one use and you’re on to the next.

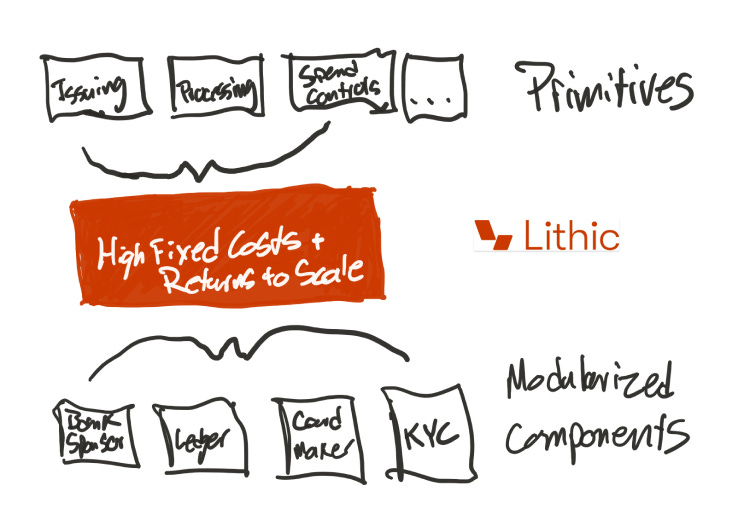

When they started in 2014, single-use virtual cards weren’t a thing. Virtual cards were barely a thing at all. To get the card product off the ground, they worked with i2c, a 20-year-old issuing company. But by 2018, CEO Bo Jiang and team realized that they needed to build their own infrastructure to support the unique needs of their own product. They rebuilt everything from the ground up as a set of issuing primitives.

Turns out, their unique needs weren’t that unique. Scores of modern fintech companies were also looking for a more flexible and modular card issuing API.

Last year, after a year of beta testing, Privacy.com launched its own Card Issuing API, making the issuing infrastructure it built for itself available to anyone. In May this year, Privacy.com announced a $43 million Series B, led by Bessemer Venture Partners, and that it was rebranding the API-first business to Lithic and moving Privacy.com under the Lithic umbrella. Two weeks ago, the company announced a $60 million Series C led by Stripes (Not Boring Capital invested in this round).

The Series C brings the company’s total funding to $110 million, with the vast majority announced within the past four months, and its valuation to $800 million. That’s rapid funding, and it matches Lithic’s rapid growth.

While Privacy.com continues to grow, Lithic is exploding. In just over a year since announcing its Card Issuing API, Lithic is handling ~20x the total payments volume (TPV) that incumbent Marqeta did in its first year with an API (2015). It’s on pace to 2-3x TPV by the end of the year.

When a company pivots its strategy and finds enormous success out of the gate, it’s worth studying. This piece is about Lithic, but it’s also chock-full of lessons on primitives, first and best customers, APIs, market segmentation, growth, and how card payments work.

Operators, investors, and the fintech-curious should all be able to learn a thing or two from Lithic. We’ll cover:

The Anatomy of a Payment

Privacy.com

The Amazon Playbook

Lithic

The Issuer Landscape

The Size of the Prize

To understand Lithic’s opportunity, we need to start in the nitty gritty: by understanding how payments work.

The Anatomy of a Payment

Moving money around is complex.

We make payments all day, every day. It’s early on the east coast, so I haven’t made one yet this morning, but judging by my credit card statement, I’ll make between three to five payments by the time I go to sleep tonight. Most of us never think about what goes on behind the scenes; we just swipe our card or enter our card details online and trust that the balance will go down in our account and the balance will go up in the account of whoever we’re buying from.

In between those two events, though, a bunch of stuff happens. In fact, there are at least five layers between the buyer and the merchant. I say “at least,” because many of these layers have multiple parties involved. Finix did a great job of breaking it down in Understanding the Payments Stack.

Broadly, there are two sides of the transaction, with rails in between:

Issuing is on the side of the person making the purchase

Acquiring is on the side of the seller.

Card networks like Visa, MasterCard, and American Express sit in between and connect the two sides.

When a transaction occurs, each party in the stack talks to the party above and below it to decide in seconds whether to accept payment, and then move money around.

Here’s how it works: when you swipe a card, it goes from the merchant acquirer to the card network to the issuer processor who decrypts and then approves or denies the transaction. Then the issuing bank pays the acquiring bank, who pays the merchant.

Let’s break it down.

Card Networks. When you hear about card payments moving over Visa or MasterCard’s “rails,” this is what it’s referring to. It means that they move money from payer to payee, from buyer to merchant. Card networks sit in an important spot in the payments value chain and they have the market caps to prove it. Visa and MasterCard’s market caps are $506 and $363 billion, respectively. They also have all sorts of power; for example, the card networks set the interchange rates, which determine how much the issuing side of the stack makes on transactions.

Acquiring. When you think about the large fintech companies, chances are you’re thinking about the merchant acquiring side of the business. Historically, when you swiped your card at a store, the payment processor gave a thumbs up or thumbs down, then facilitated money moving from the issuing side through the card network and to the acquiring bank, which then sent the money to the merchant.

Fintech giants like PayPal, Square, Adyen, and Stripe represent a recent addition to the stack called payment facilitators. They either sit on top of the payment processors, or replace the payment processors and work directly with the acquiring bank (see: Stripe + Wells Fargo) to let merchants accept online and digital payments. Stripe has a good overview of “payfacs” here.

Most of the innovation in payments over the past couple of decades has happened on the acquiring side. For the internet to live up to its promise, online merchants needed to be able to easily accept payment, and PayPal, Square, Adyen, Stripe, and others have built large businesses making that possible. In doing so, they have dramatically expanded the market. It’s no coincidence that Stripe’s mission is to “increase the GDP of the internet.”

Issuing. On the issuing side, there are two main parties: issuing banks and issuing processors. Issuing banks are banks that issue cards on behalf of the card networks. Issuer processors work with the card network and issuing bank to approve transactions in real-time at the point of sale. Issuer processors -- including incumbents like i2c and TSYS, newer players like Galileo and Marqeta, and Lithic -- don’t issue cards themselves. They work with issuing banks who do.

Legacy issuer processor giants like TSYS work with big banks who are both issuing banks and own the customer relationship. In this case, the bank has the power. Newer players work with sponsor banks, issuing banks who provide the Bank Identification Number required but don’t own the customer relationship. Marqeta, for example, uses Sutton Bank to issue most of its cards, whereas Lithic can work with any issuing bank its clients use.

Adding one layer to the stack, issuer processors like Lithic allow neobanks and other non-bank companies to embed financial products into their offering -- “embedded finance” -- adding another player on the issuing side: the client. Together, the client, Lithic, and a sponsor bank perform the function of a card issuer. In this model, the clients have the power and the banks are modularized.

To date, there has been a ton of innovation on the acquiring side. Stripe, Square, PayPal, and Lightspeed are worth over half a trillion dollars combined. They made it possible to enter a traditional credit card, or connect a bank account and pay via ACH, on nearly any website to purchase items.

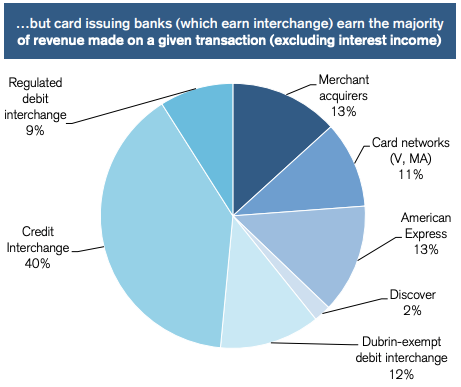

There has been less innovation and value creation on the issuing side. But the issuing side is actually where more of the value is captured in the transaction. Check out this chart from Finix:

Whereas the acquiring side takes a 50-100 bps “markup,” and card networks grab ~15 bps on pretty much everything, ~175 bps in each transaction go to the issuing bank and processor in the form of interchange—the lifeblood of fintech. As I wrote in Ramp’s Double-Unicorn Rounds:

Ramp makes money on interchange. Like a normal credit card company, it takes a 1.5%-2.5% fee on transactions (paid by merchants/card networks) when customers spend using the card. Unlike a normal credit card company, it doesn’t reward users with points; it rewards them with better software. Better software drives more usage, which drives more revenue, which drives better software, and so on.

The challenge was: banks like Chase and Bank of America have historically owned the customer relationship and therefore captured most of the value from interchange, leaving little room for issuing-side fintechs. No financial opportunity, no innovation.

But embedded finance changed that. On the internet, whoever owns the customer holds the power. When tech companies with millions of customers started offering financial products directly to those customers, without needing to go through Chase or Bank of America, they shook loose a ton of interchange to split among the client and the issuer processor.

Thanks to Marqeta’s recent IPO and corresponding S-1, we have some visibility into how that ~175 bps of interchange is split up in this emerging world order (it’s a little lower than 175 here because debit and prepaid card transactions have lower interchange):

Lithic exists to help its clients capture their bps and to capture some bps itself for making it easy for any company to issue physical and virtual cards and process transactions.

Where does the money come from? The merchant ultimately pays the fees for both sides of the transaction, with the ~3% of revenue coming out of gross margins. That 3% on everything funds an entire industry full of unicorns, decacorns, and centacorns.

OK, so now that we understand how a payment works, we can turn our attention to Privacy.com and begin to understand why they needed to build their own infrastructure.

Privacy.com

Before Lithic, there was Privacy.com, and before Privacy.com, there was … Bitcoin?

Bo Jiang, Lithic’s founder and CEO, is smart. He graduated from MIT with a BS in Applied Mathematics, worked in the famed MIT Media Lab, and then went to work for IAC. While he was at IAC in the early 2010s, he started getting really into crypto, and he decided to strike out with his co-founders, Jason Kruse and David Nichols, to build a Bitcoin-backed debit card.

The problem was, the banks hated the idea, and as we learned above, you need to work with a bank to do anything in payments. As Bo told Anthony Pompliano:

We talked to 50 banks at the time. The responses from the banks fell into two categories. You had banks that didn’t know what Bitcoin was, who were naturally risk-averse, who were like, ‘No this isn’t for us—let’s wait a few years.’ Then you had banks that were more forward-looking and knew what Bitcoin was, who were like, ‘Definitely no. The door is there. Get out.’”

Turns out, Bitcoin didn’t fixes this. So he went back to the drawing board and thought about what value Bitcoin provided: security, privacy, and pseudonymity. Even without using Bitcoin itself, he realized that he could deliver those values to customers with virtual cards. Privacy.com was born.

With Privacy, users connect a funding source and installed a plugin or mobile app, and Privacy auto-generates and autofills a new card number and details every time you purchase something online. If the website on which you’re shopping is hacked, you’re safe. If you want to cancel a subscription on one of those sites that makes it really hard to cancel, just cut off the card.

Privacy was very early to the virtual card game. Marqeta didn’t have APIs when Jiang founded Privacy in 2014. Stripe was still exclusively focused on the acquiring side. So Privacy was forced to go with a legacy issuer processor, i2c, to get off the ground. The process was long (12+ months), expensive (half a million dollars), and full of paper work and price obfuscation. There were no publicly available APIs. It didn’t move at the speed of the internet like Privacy needed. Worse, it wasn’t even that stable.

At that point, Privacy sat at the edge of the payments stack in the “Client” role between the issuer processor and the buyer. It needed to go deeper down the stack.

So in 2018, Privacy decided to build its own issuer processor infrastructure. The decision meant investing in high fixed costs that would ultimately improve performance and lower marginal costs. It needed to establish a relationship with a sponsor bank and write software to authorize transactions, route and orchestrate settlement and clearing messages, and handle reporting, reconciliation, and movement of funds between all relevant parties.

It essentially built a whole issuer processor to serve just one customer: itself.

The Amazon Playbook: Primitives and First & Best Customer

Ben Thompson kicked off The Amazon Tax with a section on AWS’ history that so perfectly fits what Lithic is doing that I’m going to copy it here (and bold some key words):

As Brad Stone detailed in The Everything Store, by the early 2000s Amazon was increasingly constrained by the fact the various teams in the company were all served by one monolithic technical team that had to authorize and spin up resources for every project. Stone wrote:

At the same time, Bezos became enamored with a book called Creation, by Steve Grand, the developer of a 1990s video game called Creatures that allowed players to guide and nurture a seemingly intelligent organism on their computer screens. Grand wrote that his approach to creating intelligent life was to focus on designing simple computational building blocks, called primitives, and then sit back and watch surprising behaviors emerge.

The book…helped to crystallize the debate over the problems with the company’s own infrastructure. If Amazon wanted to stimulate creativity among its developers, it shouldn’t try to guess what kind of services they might want; such guesses would be based on patterns of the past. Instead, it should be creating primitives — the building blocks of computing — and then getting out of the way. In other words, it needed to break its infrastructure down into the smallest, simplest atomic components and allow developers to freely access them with as much flexibility as possible.

The “primitives” model modularized Amazon’s infrastructure, effectively transforming raw data center components into storage, computing, databases, etc. which could be used on an ad-hoc basis not only by Amazon’s internal teams but also outside developers:

This AWS layer in the middle has several key characteristics:

AWS has massive fixed costs but benefits tremendously from economies of scale

The cost to build AWS was justified because the first and best customer is Amazon’s e-commerce business

AWS’s focus on “primitives” meant it could be sold as-is to developers beyond Amazon, increasing the returns to scale and, by extension, deepening AWS’ moat

This last point was a win-win: developers would have access to enterprise-level computing resources with zero up-front investment; Amazon, meanwhile, would get that much more scale for a set of products for which they would be the first and best customer.

OK, back to my own words.

This describes what Privacy did, and why, almost perfectly, with a few unique twists:

Privacy was constrained by using one monolithic provider (i2c)

It built its own infrastructure using a set of primitives that could be used by Privacy’s internal teams

Building its own infrastructure had high upfront costs and benefits from economies of scale

After using its new infrastructure itself in 2018, Privacy noticed something interesting happening: external developers were trying to reverse-engineer its internal APIs.

That was a pretty strong early signal that they had a unique solution that others might want to buy, so they decided to experiment with exposing them to outside developers, starting with a small beta in 2019. They launched the Privacy Card Issuing API in 2020, and found more similarities with Amazon:

Its API is used on an ad-hoc basis not only by Privacy’s internal teams but also outside developers

When developers got their hands on Privacy’s APIs, surprising behaviors emerged

The cost to build the Card Issuing API was justified because Privacy would become its first and best customer

Its focus on speed, modularity, and API-first model meant that it could be sold to developers beyond Privacy, increasing returns to scale

Customers loved the API. The pull was so strong that Privacy decided to make the API its main focus. In May, in conjunction with its $43 million Series B, Privacy announced the launch of its card issuing platform, Lithic, and the rebranding of its main enterprise from Privacy.com to Lithic. Then it quickly raised an additional $60 million in July’s Series C at an $800 million valuation to lean into the market pull. Lithic was born.

Lithic

Privacy.com, Lithic’s B2C product, is a strong, cash-efficient business that serves a niche of people who care about privacy and security well.

Lithic, the card issuing platform, is an absolute card rocket. 💳 🚀

In its S-1, card issuing incumbent Marqeta included a chart highlighting its strong TPV growth from the launch of its API in 2015 through 2020. It’s an impressive chart with the kind of compounding growth that investors love to see: 10x, 3x, 4x, 3x, 3x.

Lithic is crushing Marqeta’s early numbers. Now, to be fair, Lithic was born into a perfect market. Both ecommerce and embedded finance have exploded over the past year. But still, it’s about to cross $1 billion in TPV a little over a year in. It expects to end the year 2-3x higher. Developer love for the product, a huge indicator of success for API-first companies, has been incredibly strong.

So what makes Lithic special?

Lithic is a modern, developer-first card issuing and processing solution for startups, fintech companies, and brands. Issuing a card used to take 6-12 months and $500k - $1 million. Legacy players are built on top of old infrastructure, like Oracle databases, that make them slow and unwieldy. Lithic is built from the ground up.

Lithic’s Card Issuing API took the primitives that the company built internally -- issuing, processing, spend controls, just-in-time funding, auth stream access -- and lets customers mix and match what they need, when they need with modularized components that they can get elsewhere, like sponsor banks, ledgers, card manufacturers, or KYC tools.

To hammer this point home: the fact that this structure modularizes sponsor banks is massive. It means most of the interchange big banks keep for themselves is now up for grabs.

Lithic’s structure is incredibly flexible. Lithic’s beauty is in its modularity.

For young startups, developers can spin up Lithic’s turnkey Starter program to issue real money cards in as little as one day. In the Starter plan, Lithic acts as the program manager and handles the relationship with the sponsor bank for the Client.

For larger fintechs and companies with more custom needs, Lithic can be fully modular. If an Enterprise client wants to use their own sponsor bank and Know Your Customer (KYC) tool, like Alloy, they can. Enterprise clients also take a higher revenue share -- more of the interchange goes to the client.

In fact, Bo told me that he thinks the API-first fintech companies that win are going to be the ones that play well with others in the ecosystem and “spike” in one or two areas. Alloy spikes on KYC. Wyre spikes on crypto. Sila spikes on money storage and ledgering. Lithic spikes on issuing and processing. Many larger neobanks and startups that want to offer financial products might use a combination of best-in-breed products to build out a suite of financial products tailored to their customers needs.

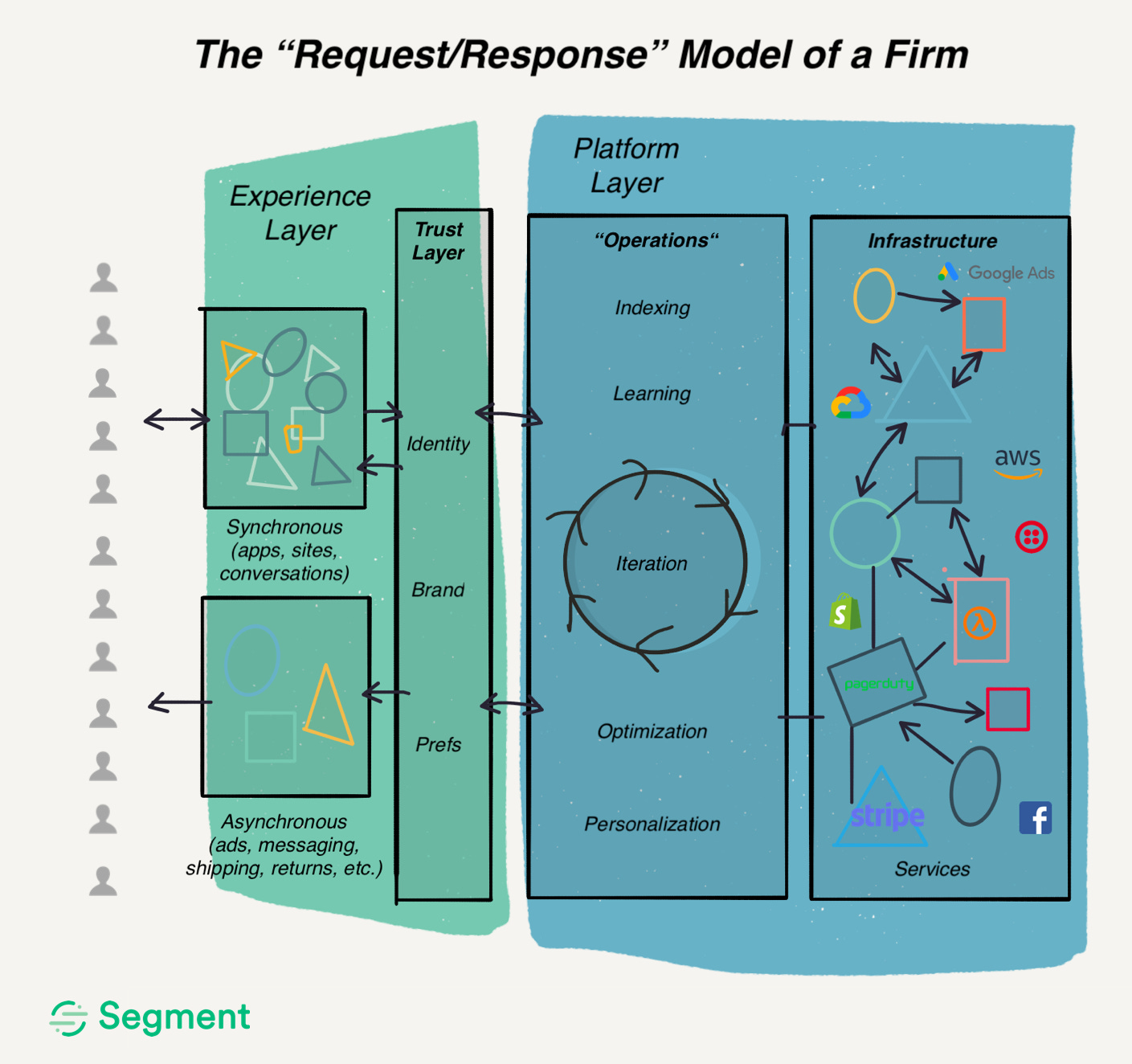

The ability to mix and match APIs changes the nature of the value chain. Stripe’s Chris Sperandio calls it the “Request/Response Model of a Firm.”

It means that, when you can call all sorts of superpowers via API, there is a competitive advantage to be gained from how you combine APIs and create workflows to build your company and product. The important skill is no longer the ability to build everything in-house; it’s figuring out the best way to combine best in breed off-the-shelf products while focusing in-house resources on points of differentiation.

API-first companies like Lithic are so powerful for a few reasons that I covered in APIs All the Way Down.

First and foremost: focus. A neobank, budgeting app, or BNPL might focus on building certain products that are specifically tailored to young people who need to build credit, or immigrants, or gamers, or any number of targeted groups of people. By working with Lithic and other API-first fintech companies, they can focus on building the things that differentiate them instead of needing to hire engineers and project managers to spend months integrating with legacy issuer processors (and years and years maintaining them).

Lithic just makes sure that their users get the physical and virtual cards they need, and that the cards work fast when needed. That requires focus in its own right: Lithic’s team is obsessed with the specific problems related to issuer processing and can spend the time and resources required to anticipate all of the little nuances and edge cases that build up to one great experience. For example, they just rolled out real-time, granular spending controls that let clients choose who can spend how much where. They call it Auth. Stream Access.

Another beautiful thing about API-first companies is that, by creating primitives and making it quick and easy to build with them, they enable new use cases. As Stone wrote in The Everything Store, they can “sit back and watchsurprising behaviors emerge.”

On its site, Lithic highlights some of the many ways that its clients are using its product.

Some were obvious -- like digital banks and expense management -- but others, like insurance or media & ad buying only happened because Lithic made it easy. Those clients didn’t shift from another solution. Lithic enabled them to embed payments for the first time.

On Fintech Today’s Tux Time podcast, Bo told Julie VerHage-Greenberg about an unexpected use case:

We’re seeing a proliferation of use cases in different industries that we couldn’t have anticipated even six to twelve months ago… We work with a commercial fleet warranty provider… Historically, if your truck breaks down, you take your truck to the mechanic, and you pay the mechanic out of pocket, it’s $10 or $20k, and you file the claim and get paid back 30 days later. With our API, the warranty provider is able to generate a card on the fly and pay the mechanic directly.

A decade ago, Stripe changed the game on the acquiring side by making it easy for anyone to accept payments online with a few lines of code. There are likely thousands or millions of businesses that would not exist without Stripe. Stripe wasn’t the first company that let companies accept payments online; in fact, many people at the time wondered why Stripe was entering the race when PayPal existed and payments were a “solved problem.” But by making it dead simple for developers, Stripe greatly expanded the market and built a $100 billion+ business.

A decade later, Lithic is hoping to do the same thing to the issuing side in the face of incumbent competitors… including Stripe itself.

Embedded Finance and the Issuer Processor Market

In July of last year, a16z’s Angela Strange said that every company will be a fintech company.

While legacy players in the issuer processor space, including Lithic’s old flame i2c and TSYS, sold technology systems to banks to help them issue cards and process transactions, Lithic, Marqeta, Galileo, and Stripe Issuing sell infrastructure that helps any technology company become a bank*. (*Hello regulators, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean that, I meant non-banks.) This trend towards technology companies embedding financial products within their offerings is called, you guess it, embedded finance.

Fintech Today’s Ian Kar defined embedded finance like this:

Embedded finance is when a non-financial services company creates financial services products for their users, embedding them into its existing products. Companies with massive distribution and powerful data moats use these assets to create unique financial products that can be easily marketed to users. By delivering more value, this becomes a useful way to increase the lifetime value of each customer.

Embedded finance covers all sorts of products:

Quip’s dental insurance is embedded finance

Shopify Balance is embedded finance

Benepass’ HSA reimbursements are embedded finance

Bank accounts, insurance, lending… if a financial institution does it, chances are, a tech company can embed it. Within embedded finance, the issuer processor side—which lets neobanks and tech companies issue cards to employees, partners, and customers and process transactions—is heating up. Lithic is one of four main competitors in the space, alongside Marqeta, Stripe Issuing, and Galileo.

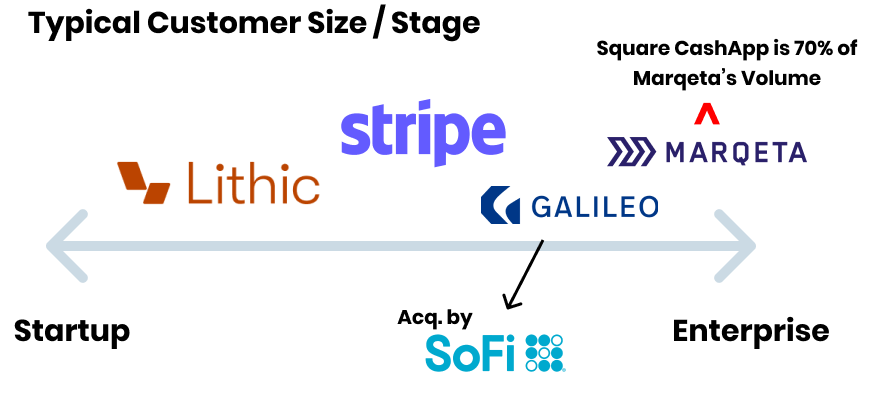

This is a sponsored post, and I’m a Lithic investor, but I’m not here to tell you that Lithic is the best option for every company that wants to issue cards. Each company is best at certain things for certain customers (and the market is absolutely enormous). According to Nikil Konduru, who heads up GTM Strategy at Lithic, there are four primary vectors along which to differentiate the players: Typical Customer Size/Stage, Use Cases, Flexibility, and Pricing.

Typical Customer Size/Stage. Lithic differentiates by focusing on earlier-stage companies than any of its competitors. It does that by reducing the traditional frictions associated with card issuing. In a product category where banks, networks, and regulators end up constructing ten-foot-tall barriers to entry, Lithic simplifies the various compliance requirements and provides a streamlined path for startups to quickly launch a card program.

Use Cases. Each company focuses on slightly different use cases:

Marqeta: Leans heavily towards digital banking because Square is 70% of its volume, but also does a good deal of Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) volume. Their earnings call yesterday (their first as a public market company) effectively confirmed that these were the two verticals driving most of their growth.

Stripe Issuing: Mostly commercial card programs -- they don’t support consumer programs yet -- including expense management platforms like Ramp.

Galileo: Supports a lot of fintech 1.0 companies, with logos on its homepage from Dave, Monzo, and MoneyLion. SoFi acquired Galileo last year, and is a big user.

Lithic: Because Lithic is the most flexible and developer-friendly on the market, and serves commercial and consumer use cases, it seems to have the widest use case mix, from insurance/warranty providers and digital banks to expense management companies and incentives & rewards programs.

Flexibility. Marqeta offers a full-suite product with everything built in, which is perfect for certain use cases that want everything in one package. Stripe Issuing is well-integrated with the rest of the Stripe Product suite. Galileo and Lithic are the most modular, but I’d stop short of calling Galileo “flexible” because they’re known to have an onerous onboarding and issuing process that includes giant due diligence checklists, which may work for larger companies but are tough for startups.

For the right type of customer, flexibility is one of the areas in which Lithic shines most brightly. The team at Lithic has built the product to pair well with best-of-breed infrastructure providers elsewhere in the fintech ecosystem: Alloy for identity verification, Plaid for open banking data and auth., Sila for money storage and ledgering, Wyre for fiat to crypto on/ off-ramps.

Pricing. Galileo appears to be the cheapest option in the category, with clean pay-as-you-go pricing for its issuer-processing technology. That said, given onerous onboarding, integration, and maintenance, all-in costs for working with Galileo are likely much higher than the list price.

Marqeta, Stripe, and Lithic all offer favorable interchange revenue share with their clients (like Square getting 80 bps per transaction from Marqeta in the illustration earlier in the piece), with Marqeta and Stripe offering better rev shares to companies at very large scale, and Lithic offering better rev shares to startups and low-volume/high-growth clients. For Enterprise clients, Lithic facilitates their going direct to any sponsor bank of their choice to really optimize their interchange revenue capture.

Interestingly, as Tanay Jaipuria pointed out, Marqeta gave options to some of its larger customers based on milestones.

Stripe takes the opposite approach: they’ve shown a willingness to invest in fast-growing startups that could be potential Issuing customers and provide last-mile touchpoints with customers.

Lithic’s Strategy

Issuer processing is not a winner-take-all market. Each major player has its own target customer and strategy to acquire and serve them well.

Lithic’s strategy is clear: go after startups with a flexible, developer-friendly product at a fair price, expand the market, and move upmarket as startup customers turn into the next generation of massive companies. It’s a smart strategy, and, ironically, one that Stripe used to great success. In Stripe: The Internet’s Most Undervalued Company, I wrote:

It began by serving an overserved segment of the market -- engineers at startups -- with a product that traded features for simplicity and speed. And it’s grown with them. Like Slack and Snap, Stripe takes advantage of the compounding effects of young users. At an increasing rate, startups become big companies, and young people become decision makers. While incumbents and other competitors focus upmarket, on the most lucrative opportunity in the present, Stripe focuses on compounding over time.

On the merchant acquiring side of the business, Stripe started with small companies and expanded with them. Now, Patrick Collison said in 2019, “Our strategy is very deliberately to serve both ends of the continuum (startups and enterprises), and every point in between.” On the issuing side, however, Stripe, the only other competitor built on modern infrastructure, seems to be focusing more upmarket, leaving room for Lithic to Stripe Stripe in issuer processing by compounding alongside smaller users as they, and the market, expand.

And the market is expanding rapidly.

Size of the Prize

Most of the innovation and value creation in the payments stack to date has been on the acquiring side. While PayPal (& Braintree), Square, Stripe, Adyen, and Lightspeed all do more than just merchant acquiring, they’ve focused most of their efforts on making it easier for businesses to accept payments.

Lithic believes there’s an opportunity for the same type of outcomes on the issuing side this decade. On Tux Time, Bo said:

I think there’s still a Stripe-, Square-, or Adyen-scale business on the issuing side. There’s no one that is really focusing on building accessible and really, really modern infrastructure around card issuance.

The market would certainly seem to support large outcomes. According to Credit Suisse’s Q1 2021 report, Payments, Processors, & Fintech, “US payment card volumes are approaching $8 trillion in total.” Who are the biggest beneficiaries? Not Visa and MasterCard, but “the card issuers themselves, with card issuers earning interchange on each transaction equivalent to ~130bps.” Interchange makes up nearly 60% of revenue in a given card transaction.

Now today, most of that goes to the banks. Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and other issuer banks work with incumbent issuer processors like TSYS, fiserv, and their own in-house processing, and the economics look very different than they do for Marqeta and Square.

Marqeta, which has a $16 billion market cap but less than 1% of the issuer processing market share, shows that clients and issuer processors capture more value than sponsor banks in the new model.

That’s an important shift. And it comes down to who owns the customer relationship.

In the old model, banks own the customer relationship and use largely commodity issuer processor technology, so banks capture most of the profits.

In the new model, which is still in its infancy, clients like Square, Uber, DoorDash, neobanks, and the thousands of other technology companies that embed card products into their offering own the customer relationship. They capture most of the value in the transaction in the form of higher interchange take. Issuer processors like Marqeta and Lithic enable new experiences with modern tech and capture the second most value. Sponsor banks are a modularized input and capture the least value.

The Credit Suisse report (p. 167) estimates a TAM for issuer processors: $15 billion. That’s tiny. But look closely, they base the estimate directly off TSYS’ market sizing.

TSYS is in a weak but comfortable spot in the value chain, taking small cuts of the banks’ interchange on 40% of all US transactions. That TAM estimate underestimates the power shift.

If companies like Lithic can shift power from the banks to new offerings that offer users better, more tailored, more transparent solutions, then the opportunity is the ~130 bps of interchange that the banks take on an $8 trillion payments market that will likely grow to eat much of the $25 trillion B2B payments market in the coming decade as well. That’s a $100 - $450 billion TAM for Clients and Issuer Processors to divide up.

Obviously, this is purely illustrative. The banks aren’t going away any time soon, and B2B payments are a tough nut to crack. But the new three-headed card issuer -- Client + Lithic + Sponsor Bank -- will steal existing share over the coming years, and create entirely new opportunities.

Successful API-first companies don’t just steal share, they expand markets. Stripe did it. Twilio did it. NexHealth is doing it. And AWS certainly did it. Tech would be a much different, smaller industry without the ability to spin up servers in a few lines of code and pay-as-you-go.

By internalizing the fixed costs and delivering flexible, developer-friendly primitives to builders as-a-service, API-first companies give thousands of people the opportunity to build creative new solutions that grow the pie by providing novel and superior user experiences.

That’s Lithic’s opportunity: to make issuing and processing as easy as accepting payments is today, and to grow with its clients as they create more and more value. In other words, to keep building new primitives and watch surprising behaviors emerge.

Go build surprising financial products.

Thanks to Yoni for the introduction, and to Bo and Nikil for demystifying payments!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Monday!

Packy

The biggest takeaway is Square is a monster: 80bp!

Nice article - one thought I had on the opportunity around cutting into the interchange banks are taking is well, is that so great an opportunity? As the banks compete very aggressively for customers with cash back offers etc which chew into those interchange profits. Looking at Capital One's most recent earnings supplement (they are largest bank issuer it appears, or at least one of the largest), their non interest card earnings is about ~$1b/quarter over the last year. However the non interest expenses are $2 to 2.3b / quarter! Obviously this doesn't break down the granular details but it seems like there is a good chance the interchange revenue is actually a loss leader to generate credit card interest income, which is around $3b/ quarter. So I'm wondering if this opportunity may prove to be a very tough nut to crack, as consumers are actually capturing much of this value here in the form of credit card rewards etc, and therefore the incentive for the average person to switch to a new platform may be low. Not to say there aren't other interesting opportunities Lithic can target, but TAM may be far smaller unless they can break into B2B, which does feel very ripe for disruption given backwards ACH/check payments.