Welcome to the 403 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Thursday! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, join 5,900 smart, curious folks by subscribing here!

Hi friends 👋🏻,

Happy Thursday! We here at Not Boring HQ always want to keep you on your toes, mix things up, try new things. Today is no different.

Let’s get to it.

Apt: The Natively Integrated Developer

🎧 If you prefer my smooth, smooth voice: Apt: The Natively Integrated Developer (Audio)

Building the Future

When I quit my investment banking job to join a startup, I thought I would be living in the future every day. But Breather is a real estate startup, and most of my time in the early days was spent begging landlords to let us lease office space, assembling furniture, and leaving Saturday night dinners to go clean up after a reservation.

That’s why I still remember the day I met Fed and Petr Novikov so clearly.

When I got to Fed and Petr’s duplex office on the outskirts of Williamsburg, the Novikovs showed me what they were building: robots that build rooms. They were living in the future.

Their ambition was inspiring. Their company, Asmbld, didn’t find traction in the office market, but they attracted Airbnb co-founder Joe Gebbia’s attention, and Airbnb brought Fed and Petr in to run its Backyard project.

Last year, when I wrote a post on Natively Integrated Companies (NICs), Fed reached out to tell me two things: 1) I got the capitalization wrong in AirBnB (it’s Airbnb now), and 2) he wanted to do a deep dive into NICs.

A year later, Fed is the first to actually go out and use something I’ve written to build a company: Apt. I was enamored for three reasons:

It solves the housing shortage in a creative, tech-based, financially savvy way.

It’s a Natively Integrated Developer (NID), a real estate interpretation of NICs.

Fed, Petr, and Apt have perfect Product-Founder Fit.

I loved Apt so much that I invested, making it my first angel investment ever.

Since Apt builds on something I wrote, Fed and I decided to come full circle and do a write up on his company. Today’s post is something new - a Not Boring Investment Memo!

A NBIM (not to be confused with NIMBY) is my thoughts on an early-stage private company, its industry and business model, the investment opportunity, and an invitation for you to check out a syndicate investing in the deal. I’ll only write them on companies I’m willing to invest in myself.

Apt is the perfect first NBIM. To understand why it’s building something special, let’s begin with the state of real estate.

1. How Real Estate Works Today

Enter The Matrix

Real estate as most of us understand it is like the simulated reality in The Matrix - pleasant to look at, relatively easy to understand, and surface level. People need a place to live or work, so they buy or rent a house or office that’s within their budget, size range, and location. But that’s not the whole story. I’m giving you a choice right now, take the blue pill and go back to browsing listings on Zillow for fun, or take the red pill, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.

(If you want to go even deeper, you should read Dror’s book, Rethinking Real Estate.)

You took the red pill. Good choice. Here’s the simple thing that will change the way you think about real estate:

A building has two core customers: its end users (people and organizations that occupy the space) and its financial backers (real estate investors and lenders).

With single family homes, the end user and the investor can often be the same person. That’s why we are so used to judging homes not only by their architectural style and neighborhood, but also their Zestimate. But when was the last time you casually checked the Zestimate of a 50-unit apartment building?

For multifamily residential buildings, there’s almost no overlap between end users and owners. According to Harvard, that leading online university, 93% of new multifamily buildings are developed as pure rentals. Over time, we tend to lose sight of how these buildings came to be and forget about their initial customers — real estate investors.

To see the world as a real estate investor is to look past the building as a physical object and see it for what it really is — a financial product. Once you master that skill, you’ve entered the Matrix: the walls are made of floating dollar signs. You live in someone’s stream of cashflows.

Each apartment building is an enterprise unto itself, and its market value is often determined by a real estate equivalent to the P/E ratio: cap rates. All things being equal, the higher the net operating income (all collected rents - operating expenses) of a building, the higher its market price in a given market.

Most real estate investment by private equity shops, family offices, and public REITs concentrates on the existing building stock. But if you’ve been to any city, from Austin to NYC, you’ve seen those cranes in the sky that indicate one thing: for developers, IT’S ALWAYS TIME TO BUILD.

Why Do Developers Exist?

As the population grows, people migrate, and old structures become obsolete, we need more new homes to be built. Actually, we really need new homes to be built. Since 2011, the U.S. has underproduced housing by 260,000 units annually. For context, that’s more than an entire city of Miami not built every year.

Creating a new building from scratch is extremely complicated. It involves finding and buying land, doing a bunch of legal and environmental due diligence, running market research to confirm the best use, getting entitlements and permits, securing investment and loans, commissioning design and engineering, overseeing construction, calming angry neighbors, doing a brand and marketing strategy to attract tenants, doing background checks, unclogging toilets, and ultimately selling the building to another real estate investor… You get the idea.

The whole process is much more taxing than investing in an existing building, and it requires someone to help coordinate it. That’s why developers exist – they get their hands dirty on behalf of passive real estate investors and lenders to see the whole project through.

Developers make their money primarily in two ways:

Collecting fees for finding the land and coordinating the project.

Receiving equity, which can generate a large payout upon the sale of the property.

Additionally, developers are often incentivized by bonuses if the project outperforms the returns promised to investors upon the project inception.

The World is Built by Shotcaller Developers

The profit of a new apartment development is the difference between the market value of a leased up property and the total cost it took to build it. Typically, development is complicated - there are a lot of moving pieces - but it’s not complex - it doesn’t call for innovative solutions to new problems. It’s a tame problem, not a wicked one.

That attracts Shotcallers. In Two Ways to Predict the Future, I wrote that Shotcallers guarantee victory, attack tame problems in big, obvious markets, and grow through brute force and big spend.

It sums up development almost perfectly. A developer’s success depends on his or her ability to do a few things:

Initial Market. Predict which people want to live in which neighborhood with what unit mix and amenities, and how much they’ll be willing to pay in rent.

Pronouncement. Raise money from equity and debt investors by providing pro formas that predict certain returns in a certain time frame.

Grow the Building. Turn the money they raise into an occupied building by managing permitting, hiring contractors to build, and marketing to potential tenants.

There is nothing wrong with Shotcalling in development! Most of the time, it’s the right approach. At this very moment, there are hundreds of developers sitting on yachts while I sit at my computer writing a free newsletter. This model has been proven by decades of successful completions, mitigated risks, fortunes for investors, and new homes for people to live in.

For the industry as a whole, though, the business model of Shotcaller developers leads to disintegration and in turn, creates barriers to innovation.

Disintegration Limits Innovation

Development is risky. The assumptions that developers make help estimate the future market value of a development and thus determine the maximum development costs they can incur. Miss the mark on that forecast, and even a flawless execution of the whole process won’t save them from failure.

The risky nature of individual forecasts leads to two things:

Developers treat all projects as independent startups to isolate the individual downside risk (if you’ve wondered why signs outside of construction projects say things like “Bond Street 273, LLC” instead of “Developer Name Inc.”, this is why).

Developers customizing every building to match their latest specific prediction and maximize profit per site.

Over time, by repeatedly treating every development project separately, the industry as a whole moved towards extreme degrees of vertical (design, construction, operations) and horizontal (specialization by trade) fragmentation. Every part of the building value chain from finance and legal, to architecture, engineering, construction, and property management has been split.

Again - this generally makes sense for each party involved! But disintegration has created a barrier for innovation in the industry as a whole. To coordinate design and construction, all industry players rely on often outdated standards and processes (some decades and even centuries old). Stanford researcher Dana Alice Sheffer found that odds for integral innovations to be implemented in the building industry are 84% lower than for modular innovations. In other words, you’re much more likely to get developers to use your new wall material than to use a product that completely transforms the way that they work.

In tech, we’re used to large companies like Apple or Google acting as industry coordinating agents. They define and frequently update platform standards for both hardware and software.

There are no Googles or Apples in the construction industry. Ironically, even though developers are coordinating agents for specific projects, they are not the coordinating agents on an industry-level, because their business model requires that they treat every project as bespoke.

That lack of integration has contributed to notoriously low productivity in the building industry, slow to non-existent meaningful innovation, and growing construction costs.

Practically, that means that we’re building fewer housing units than we need. And like any big problem, housing has attracted a wave of entrepreneurial interest.

Housing and Entrepreneurs

In the last decade, the housing crisis has become a common conversation topic. There is not enough housing, and housing development is often too expensive to make financial sense. This flashing-neon problem attracted a new wave of tech entrepreneurs and venture capitalists interested in changing the world.

The only way to significantly reduce housing development costs is to radically standardize development and harness all the economies of scale by sharing costs between multiple projects as well as leveraging industrialization and prefabrication, the same way it’s done in manufacturing.

Building prefabrication is not new, and there are many large builders in the space (e.g. Katerra) trying to get to some level of standardization. But the prefab manufacturers still have to cater to the needs of their developer clients who optimize for squeezing inches from each specific project by making them bespoke, instead of optimizing for cost reduction at a scale. In turn, this limits prefab manufacturers’ ability to standardize their building systems and reach true economies of scale.

Like so many SoftBank-backed Shotcallers that have tried to spend their way to success, Katerra is facing some challenges after raising over $1 billion from Masa. It recently laid off 400 employees - which is mind-blowingly only 7% of its staff.

Spend anything, growth-at-all-costs startups have fallen out of favor since WeWork’s downfall. Investors now focus more on unit economics and profit margins. At the same time, taking a pure software approach to the development process requires buy-in from many fragmented pieces of the development value chain, doesn’t afford the company enough control over the process to build a world-class final product, and doesn’t capture enough of the value it theoretically creates.

Luckily, there’s a model that I wrote about, and that Fed and I have spoken about many times, that fits development perfectly: NICs.

2. Apt: The First Natively Integrated Developer

In The Rise of the Natively Integrated Company, I defined a NIC as one that:

Leverages technology to integrate supply, demand and operations from day 1

Builds relationships with customers to build products that resonate

Takes principal risk to achieve 1) and 2) and capture larger share of profits

Examples include companies like Harry’s, which bought its own razor factory to improve the product and capture more margin while building direct relationships with consumers.

Apt is a Natively Integrated Developer, and its model is potentially more powerful than the NICs I wrote about. Here’s how it works.

Apt is creating a nationwide housing development chain by standardizing its products on a building level. If it is successful, it will create thousands of housing units at affordable prices by facilitating the development of low-rise apartment buildings on lots that are currently used for single-family homes. Unlocking those lots means that eight families might be able to live where only one does currently, that eight tenants might split high property taxes, and that municipalities can continue generating much needed tax revenue.

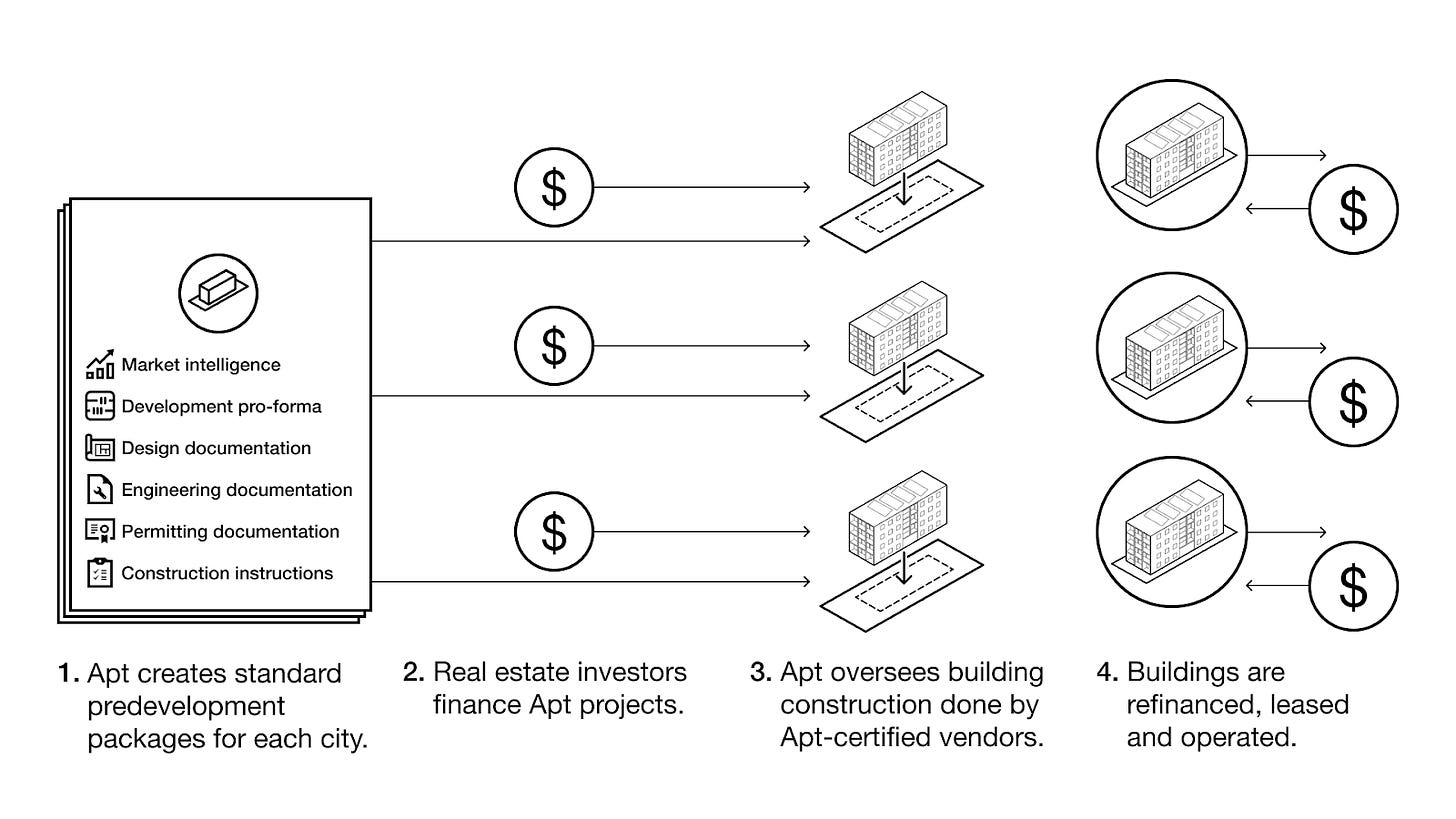

Apt’s magic is that it creates a standard pre-development package once (design and engineering development, financing terms, permitting documentation generation, construction instructions and prefabrication) for every market it operates in, and then develops multiple copies of the same building. It works the same way that software does: high upfront costs, low marginal costs. This approach has the potential to reduce building costs by over 20% and, more importantly, cut the development timeline in half. This is what a typical deal looks like:

Through its proprietary technology, Apt finds a promising lot, automatically generates pro-formas, and proposes the project to real estate investors. Apt provides its standard predevelopment package as equity contribution alongside the investors.

Once the project is financed, Apt coordinates the development, submitting the designs to the city and to certified manufacturers and general contractors (GCs).

Once the project is completed, Apt leases the building and manages the property. Learning from the building performance, Apt updates its initial pre-development package.

Looking at the real estate development value chain, Apt is the only company that integrates investment management, development coordination, and design and engineering, while modularizing (no pun intended) manufacturing and construction.

New development has the highest annualized returns potential among real estate investment alternatives, but comes with the highest risk. By making the process more repeatable and predictable, Apt reduces the risks of ground up development, while maintaining a high yield for investors.

Apt makes money from one-time development fees, recurring property management fees, and most importantly, long-term equity in the buildings. Its model is a hybrid between franchisor, operator, and investor. As Apt receives equity in buildings for each in-kind copy of its pre-development package, it’s incentivized to hold and operate the buildings and form long-term relationships with people who live in them.

Apt started with an insight that in order to integrate the value chain in the building industry and allow for innovation, you need to start by working directly with a building’s first customers — real estate investors.

In practice, that means creating a new kind of a developer with a business model designed around repeatable, not bespoke, projects, which allows Apt to fully control the level of product standardization across the end-to-end value chain.

In other words, Apt is a NID because it:

Leverages technology to source lots, and standardize design, engineering, and construction processes.

Builds direct relationships with both of its customers: investors and tenants.

Takes principal risk by creating a standard development package for each city, for which it receives equity in every project.

Apt partners with certified prefab manufacturers and GCs instead of building those capabilities in-house, primarily focusing on developing software, finance, and management tools and processes. It’s integrating the customer-facing and scaleable pieces, and modularizing the most capital-intensive, least scaleable pieces.

To start, Apt is focusing on investors, but the relationship with the renters who will live in each building is no less important for a NID.

In a traditional model, the developers tend to sell off the building as soon as it reaches stable occupancy. They don’t build lasting relationships with their tenants and don’t care what happens with the building after it’s sold. There’s no feedback loop to improve the way buildings are built and operated, and some developers get away with creating low quality products (putting lipstick on a pig) that last long enough to sell.

For a NID, it’s crucial to learn from the end-users of a building and create a feedback loop that continuously improves their product. Apt’s approach incentivizes the company and its partners to get the designs, tools, and processes right, because they will scale each of those over hundreds and eventually thousands of projects.

3. Investing in the Future of Real Estate

There are three main reasons I’m so bullish on Apt as an investment.

1. Housing Opportunity

The US housing market is so big it’s hard to wrap your head around - $33.6 trillion, according to Zillow, or 22 Amazons. More specifically to the segment of the market Apt is attacking, there are hundreds of thousands of lots zoned for multifamily that currently have single-family homes on them. 57,000 of them in are in Apt’s first market, Los Angeles. With a traditional development process, building multifamily homes on those lots wouldn’t be feasible - they’re small projects, each of which needs new plans and engineering, and takes too long for the numbers to make sense. By cutting project costs by 20% and timelines by 30%, Apt makes 2.5x more projects possible, expanding the opportunity and building much needed housing.

2. Natively Integrated Model

Apt is the first company built with the Natively Integrated framework in mind, and they’ve improved on the model. Whereas NICs take principal risk to capture a larger share of the profits, Apt takes principal risk in developing its predevelopment package, and captures a share of equity in each project. It can develop that package once in each city and use it to develop, and receive equity in, multiple copies of the same building. At thirty buildings, Apt makes $4.5 million in development fees, $1 million in recurring revenue, and owns equity in the buildings worth $15 million. Real estate is massive, and this is one of the most elegant models I’ve seen to extract high-margin revenue from the value chain.

3. Product-Founder Fit

Fed and Petr are technologists who have become real estate people and strong businessmen. When I first met them, they were entrepreneurs building incredibly cool tech too early. Since then, they’ve learned about the business side of real estate and running an at-scale startup by leading a team inside of Airbnb. When I first spoke to Fed about Apt, it was clear that he had developed a pragmatism and strategic savvy to go with his deep technological knowledge. It’s a killer combination.

Certainly, as with any startup, and particularly one that’s taking on a complicated, atoms-based industry, there are risks. Construction is messy and prone to delay, NIMBYists might fight multifamily in their neighborhoods, and customer preferences change rapidly. I created a Google Doc with five things that could go wrong, and opened it up for comments so you can add your thoughts. Check it out:

Those challenges are real, but Fed and Petr are taking a thoughtful approach towards addressing them, and they’re not enough to scare me away.

When I write about public companies in Not Boring, I get so excited that I put my money where my mouth is and invest. I’ve either started or added to positions in Snap, Spotify, Slack, Disney, and Zillow after writing about them, and built a live-updating Not Boring Portfolio to keep myself honest.

Typically, that’s not an option when I write about private companies. This is a special one though, because I believe so much in what Fed and Petr are doing that I made my first angel investment ever in Apt.

Verified Not Boring

Since last Thursday, five new people have become Verified Not Boring - huge thanks to each of you, and to Hunter Walk, the first person to cross the century mark 💯.

Gilang Ramadhan, David Namdar (Abound Capital), Tommy Gamba (Not Boring), Roman Tsegelskyi (Kalon.Tech), Rob Litterst (Good Better Best)

To become Verified Not Boring, head to our referral page and enter your email at the bottom to get your unique code. Then share away - the race to 10k is on!

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Updated the link to Jonathan's syndicate: https://angel.co/jonathan-wasserstrum/syndicate

This is absolutely correct at so many level:

1. the developer creates a "failure" in the capital market by preventing adequate feedback to capital: those that use the space cannot directly feedback to those that create it what they would be happy to pay more for. The housing market is organised like a centrally planned economy: the result is that consumers are being served bad products (car equivalent of Lada)

2. the creation of space could be much more efficient if it had a stable demand; this is possible once the demand aggregator is a long term supplier, rather than a project-based demand. In that context the creation of space will become a supply chain vs supply chain competition (as in every other industry) leading to re-organisation and optimisation: think lean, think electronic, think Apple.

Society and consumers are the winner.