Antara Health: Natively Integrated Healthcare

The Virtual-First Virtuous Cycle for Emerging Markets Healthcare

Welcome to the 1,089 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you aren’t subscribed, join 30,917 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen here on Spotify.

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Future

This may surprise you, but writing a newsletter from home and having a new baby are not conducive to peak physical fitness. I started running a little bit, and then stopped, and did some pushups, and stopped, and... I may have put on a couple of pounds.

So in December, I signed up for Future, a 1-on-1 remote personal training app. Through Future, I get to work with a world-class coach, Alex, whose clients include NBA players. Alex designs personalized workouts for me, gives daily feedback, and provides much-needed accountability. Since starting with Future, I’ve worked out 19 out of 20 days, and I’m finally getting back in shape. It feels awesome.

In the spirit of accountability, I’m going to post my progress here every couple of weeks. The only thing more motivating than Alex making sure I work out is sharing my progress with all 30,917 of you!

If you, too, could use some direction and accountability, sign up for Future. And if you’d like to try your first month free, reply to this email and I’ll send you a Guest Pass.

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday! And to those of you in the US, Happy Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

Typically, I don’t send on holidays. They’re a day to turn off your brain and not think about work or anything tangentially related for a little while. MLK Day, though, is supposed to be observed as “a day on, not a day off.” It’s the only federal holiday designated as a day of service to encourage all Americans to volunteer to improve their communities.

Now today’s essay isn’t about volunteering, it’s about an investment. And it’s about improving the global community, not my local one. But it’s hard to imagine another startup that, if successful, will have a more positive impact on the world’s emerging middle class than Antara Health.

Today’s Not Boring Investment Memo is going to be a hybrid of a typical Monday essay and an investment memo. Investment memo in that the Not Boring Syndicate has a chance to invest in Antara; Monday essay in that we’re going deep into telehealth and emerging market healthcare.

I’ve avoided writing about anything in healthcare because, frankly, it just seems so messy and confusing, and there are other sectors, so I just kind of moved on. But in the same way that mobile leapfrogged desktop computing in many emerging markets, healthcare solutions in emerging markets have more leeway to build the right thing without legacy baggage.

So today, we’re going to look at healthcare through Antara’s approach to extending lives in emerging markets. And there’s a little something for everyone:

Generally Curious People: an understanding of how healthcare works in markets where there’s not so much red tape that it’s incredibly difficult to innovate.

Founders: Understanding of the opportunities represented by a ballooning middle class, and of a business that uses technology where it should be used so humans can focus where they are best.

Let’s get to it.

Antara Health

Healthcare in emerging markets is broken. Billions of human beings don't see a doctor until it's too late, then get overcharged and treated poorly. There is over $100 billion in private healthcare spend in emerging markets, and 100 million people fall into extreme poverty because of a catastrophic healthcare expense. As the global middle class grows, the problem, and the opportunity to solve it, grows with it.

Antara Health, based out of Nairobi, Kenya, is building the solution: virtual-first primary care for emerging markets. The Antara team is redefining what’s possible in healthcare by combining telemedicine and health navigation into a product that provides better outcomes to patients and better economics to insurance providers.

I’m impressed by Antara Health for six reasons:

Extending and Improving Billions of Lives. Billions of people in emerging markets are uninsured, creating a vicious cycle in which illness leads to poverty.

Radical Changes to a Massive Market. COVID made telehealth more prevalent worldwide, creating an opportunity to radically rethink healthcare.

Antara: Natively Integrated Healthcare. Antara combines Health Navigation, telehealth, and data in a Natively Integrated approach to healthcare.

Strong Early Traction. Antara completed a successful pilot in Kenya that showed strong engagement, scalability, value, and effectiveness.

Antara’s Business Model. Healthcare doesn’t have to be complicated. Antara’s model generates recurring revenue, and it uses technology to lower costs as it scales.

The Antara Team. The Antara team is world-class at exactly the things they need to be to reimagine virtual-first primary care company for emerging markets.

I’ve largely avoided writing about healthcare because the problems are so massive and so complex, but by the same token, the impact that successful innovative healthcare companies can have is equally enormous. In Antara’s case, the problem, and opportunity, is to extend, improve, and save billions of lives.

Extending and Improving Billions of Lives

Solving healthcare for billions of people is a daunting task. It’s even daunting to write about. So let’s break it down and focus on Kenya, Antara’s first market.

Only 2.8% of Kenyans have health insurance. Most of the country’s growing middle class, those who can afford healthcare at all, pay out-of-pocket. Because they’re paying out of pocket and don’t know how to navigate the healthcare system, most people stay away and cross their fingers. It creates a perverse lottery: either you get lucky and don’t get sick, in which case you save what you would have spent on insurance or doctor’s visits, or you get very sick, sick enough to go to the doctor, and accept the real risk that healthcare costs may thrust you back into poverty.

But it’s a reflexive lottery, one in which the odds get worse just by playing. People don’t go to the doctor because they don’t want to pay out-of-pocket, which means they don’t catch things early, which means a higher likelihood of getting very sick, which means a higher likelihood of going broke in a last-ditch attempt to cure an illness when it may be too late.

And Kenya is actually the sixth most insured country of forty-one in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ghana, where my sister lives and runs OZE, ranks 17th at 1.1%. Guinea, where she spent two years as a Peace Corps Volunteer, ranks last: 0.04% of the population there is insured. We (rightly) complain about the broken insurance system in the United States, but 92% of the population here is insured.

Low insurance penetration is a bigger issue now than ever before as the incidence of chronic conditions increases. Today, up to 50% of Kenyans now have or are at risk of developing a chronic condition like diabetes or obesity, many of which are preventable if warning signs are caught early.

The vicious cycle that prevents early detection and pushes individuals into poverty also hurts insurance providers. Without the habit of engaging proactively with healthcare, even insured people seek treatment too late in the game, when care is most expensive to deliver. As a result, almost every health insurance company in Kenya is losing money, and it’s so bad that reinsurers have stopped backing them. Until now, the only things they could do were to charge higher premiums, make more exclusions, and set stricter limits, all of which push people away from getting insurance in the first place, accelerating the downward spiral.

Kenya is not unique. This same vicious cycle plays out over and over again, across the globe. As a result, according to the WHO, about 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty because of healthcare costs worldwide, and insurers struggle to find a business model that works.

The problem is so large as to seem intractable.

Then COVID hit, and presented an incredible opportunity to radically change healthcare in emerging markets.

The Opportunity: Radical Changes to a Massive Market

Telehealth on the front-end combined with intelligent software in the back-end makes previously unfeasible models feasible. COVID has created a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reimagine how healthcare should work.

By pushing people to seek services online, COVID increased market readiness for telehealth from 11% pre-COVID to 76%, according to a McKinsey study.

That represents a dramatic shift in the way that one of the world’s largest industries operates. In its 2020 Global Health Care Outlook, Deloitte pegged the size of the global healthcare market at 10.2% of GDP, or over $13 trillion annually, and it anticipates a 5% CAGR for healthcare spend through 2023. The World Health Organization (WHO) pegged the number at $7.8 billion in 2017 in its 2019 Global Spending on Health report. In either case, healthcare spend is massive.

Increasingly, although it’s still early innings, that spend is going to telehealth and virtual care. Prior to COVID, reports estimated the global telehealth market somewhere between $10-60 billion, still a tiny fraction, of overall spend, and project it to grow at around a 25% CAGR over the next five years. COVID, as it’s wont to do, dramatically accelerated that growth and the financial position of American telehealth and virtual care companies.

Amwell, which makes a white-label telehealth solution, went public in September at a $4 billion market cap, and its shares have risen 63% since, to a $6.9 billion market cap. It just priced a secondary offering in which it will raise over $300 million.

OneMedical, which offers primary care virtually or in-person at its network of 90 physical locations, went public in January at a $2 billion market cap, and has nearly tripled to a $5.7 billion market cap despite its physical footprint.

Hims, which bills itself as “telehealth for a handsome, healthy you,” is going public via a SPAC. At the time of the announcement, the company was valued at $1.6 billion, and it’s risen 80% since to $2.9 billion.

Ro, a “patient-driven telehealth company that aims to be a patient’s first call,” launched a COVID telehealth assessment early in the pandemic, and raised $200 million at a $1.5 billion valuation in July.

In August, Teladoc merged with Livongo to combine Teladoc’s leading telemedicine platform with Livongo’s chronic disease management platform. Teladoc’s stock is up 140% over the past year, and the combined company has a $33 billion market cap.

Nikhil Krishnan of the excellent health tech newsletter Out of Pocket wrote a great analysis of the Teladongo merger, which includes a few points that are particularly relevant to Antara:

Even though Teladoc engagement is low, the buyers - HR departments at companies - like the predictability of the spend and how Teladoc looks on its benefits page.

Combining telemedicine and chronic disease management gives “Teladongo” the ability to increase engagement and cross-sell (“patient steerage”).

“Telemedicine 1.0 was about getting the face-to-face visit online and people focused on how it would make it more accessible for people that found it difficult to physically get to in-person care. But the real promise of telemedicine is to create entirely new workflows, triage the kinds of labor used, and actually change the economics of visits.”

Every single company in healthcare wants to own the “front door” of healthcare and be the point of contact for patients when they need anything.

In America, the spend per patient is much higher than in emerging markets, which means the immediate financial opportunity is greater. But the American market also presents more competition, more deep-pocketed incumbents, and more onerous regulation. Emerging markets present an opportunity to serve billions of people with new solutions built from the ground up.

In many ways, emerging markets present a better opportunity for healthcare startups:

Regulators are welcoming of insurance penetration, given the low levels highlighted above and the fact that insurance is the best way to stabilize a growing middle class.

Emerging markets are often less controlled by incumbents and special interests.

There is a large pool of customers who were previously unserved or deeply underserved. Globally, over 1 billion people entered the middle class over the past ten years.

Healthcare spend is growing faster in emerging markets than developed ones.

According to the WHO, in middle income countries, including Antara’s first market, Kenya, health spending rose 6.3% a year between 2000 and 2017, nearly double the global 3.9% rate, and outpacing the broader emerging market economies’ 5.9% growth.

Reinsurers estimate that there is a $250 billion premium gap for the emerging middle class globally, as insurance penetration rises from current 1-3% levels up to at least 8-10%. The opportunity for HealthTech in emerging markets has double-tailwinds: 1) the economies are growing more quickly than developed countries, and 2) healthcare and insurance spend as a percentage of the total economy is growing.

Zooming in on Africa, the Afrobility podcast (a go-to for me) did an episode on African HealthTech in October that you should listen to if you’re interested in learning more.

The hosts, Olumide Ogunsanwo and Bankole Makanju, highlight some incredible statistics. First, while Africa has 25% of the global disease burden, less than 1% of healthcare spend occurs on the continent. Second, the average life expectancy in Sub-Saharan Africa is 61 versus 77 in China and 78 in the United States.

Third, Kenya spends $76 per citizen per year on healthcare compared to over $10,000 in the US.

But spend only tells part of the story. According to Olumide and Bankole, Healthcare in Africa faces real challenges:

Talent and Brain Drain. Africa has a shortage of healthcare workers (less than 10% of what they need for primary care). There are 8,000 Nigerian doctors in the US compared to 35,000 Nigerian doctors in Nigeria. HealthTech companies need to figure out a way to get more out of fewer doctors.

Logistics and Cold Chain. Drugs and vaccines require cold storage and transportation, which can be difficult when electricity is often unreliable.

Insurance. As covered above, a tiny percentage of people are insured.

There is a clear need for new solutions, and new companies are working on them. HealthTech as a percentage of African venture funding grew from 2-3% in 2018 to 8-9% in 2019. The Afrobility hosts cite examples across a few categories: Patients, Payors (I’m going with the spelling Antara uses), Providers, Manufacturers, Distributors, and others. The most relevant are:

Babyl: Spun out from Babylon Health in the UK, Bably provides chatbot consultation, ML-based diagnosis, doctor visit booking, and live video and audio sessions.

mPharma: The Ghana-based company manages prescription drug inventory for pharmacies to make drugs more affordable. mPharma has raised $55 million in the past five years, including $17 million in 2020.

BIMA Health: Founded in Stockholm in 2010, BIMA offers mobile-delivered microinsurance and serves ten countries, including three in Africa. Members can buy insurance on their phone with airtime credits and book appointments with doctors. The company has raised $200 million.

Zipline: The San Francisco-based company has raised $233 million to develop drones that can deliver medication to remote areas.

MTN Ayo: Like BIMA, Africa’s leading telco offers microinsurance that people can purchase with airtime credits. They can submit claims directly through WhatsApp.

These examples show that there is investor appetite for Africa-focused HealthTech companies. Each one though, tackles only a small slice of the problem. The hosts cite China’s Ping An or Brazil’s Doctor Consultor as examples of what HealthTech could be in Africa. Then Bankole said something that made my ears perk up:

The ones that I’ve seen scale in these emerging markets have been vertically integrated.

Antara Health is building a Natively Integrated company to change how healthcare happens in emerging markets by helping each health professional serve more people and making insurance affordable for a wider swath of the population.

Antara Health: The Natively Integrated Healthcare Company

Antara feels like what Teladongo would build if they could start fresh. It’s reimagining healthcare by leveraging telemedicine, data science, and emerging markets payors’ and regulators’ willingness to try new models. They’re building virtual-first primary care, a new model of healthcare that integrates life and health protection using data.

It’s a Natively Integrated Healthcare Company. In The Rise of the Natively Integrated Company, I wrote that Natively Integrated Companies (NICs):

Leverage technology to integrate the customer-impacting components of their value chain, build relationships with customers, and are willing to commit capital to build products that resonate with them.

The Natively Integrated model works particularly well for problems that have been historically difficult to solve due to challenges with coordination and incentive alignment among different stakeholders. It’s why I’m so bullish on Apt’s approach to real estate development.

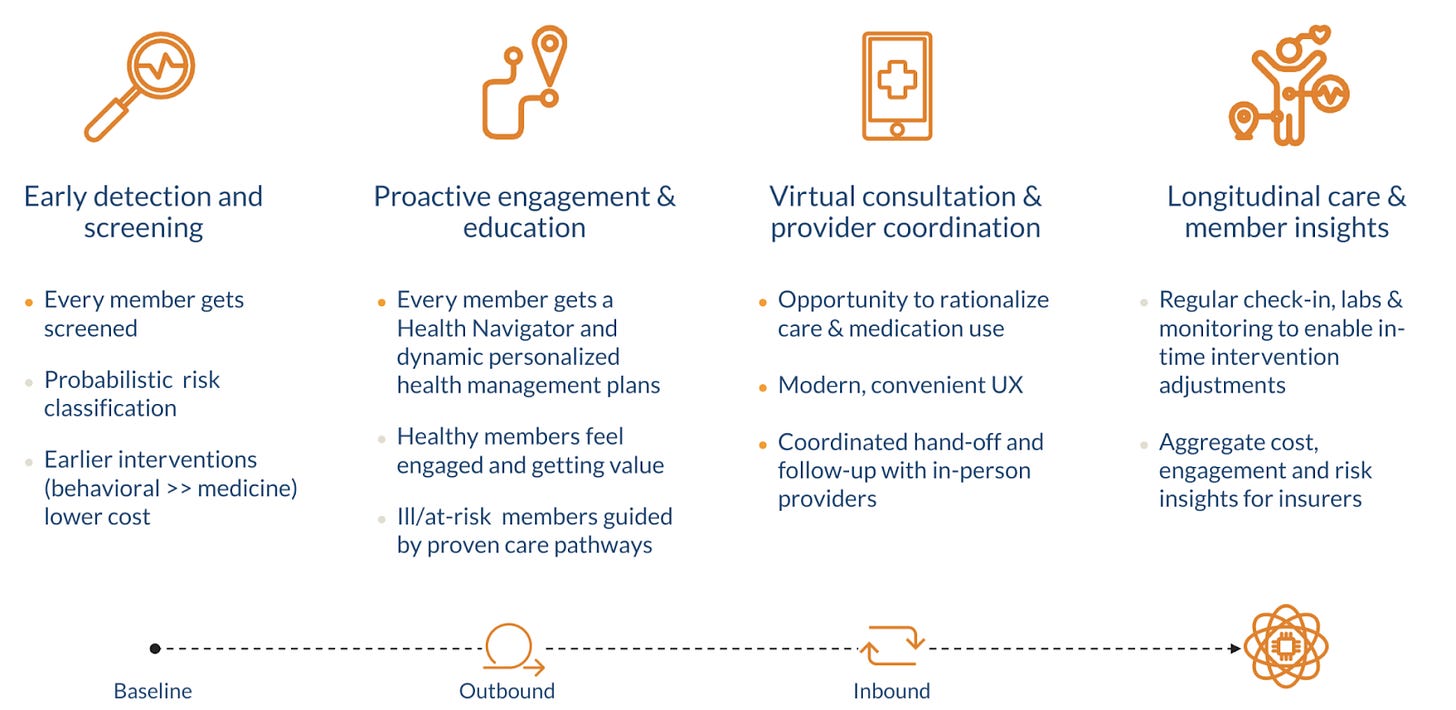

In Antara’s case, the company’s Health Navigation is the missing layer to primary care. Telemedicine, e-triage, care coordination, remote monitoring, digital health counseling, and digital therapeutics all have been proven to improve health, but in piecemeal, struggle or fail to fully address patient needs and realize their potential. Antara’s solution is a strategic slice of all that, integrated.

Antara simplifies all of the complexity to a single trusted source that guides a patient’s healthcare journey, and leverages technology in order to scale the human touch. It even has virtual care doctors on-staff, and can cover 50-70% of primary care cases within Antara’s care. The company specializes in chronic condition management and puts mortality at the forefront as the objective, asking the one question that every health professional should be asking: Are we improving and extending patients’ lives?

Everything the company builds is integrated around that question. Here’s how it works:

Every Antara Member gets assigned a Health Navigator, a trained nurse whose sole job is to coordinate all that complex care for Members in a comprehensible, easily accessible, and cost-effective manner. In the beginning of a Member’s journey, Antara screens them for chronic conditions.

Antara then uses its own risk models and taps into unique mortality models built on data only available within the largest and longest-standing life insurance companies. They're particularly excited about using a quantitative mortality score as an internal indicator to drive the progress of their members. Think of it as introducing a new objective function into healthcare.

If a Member is healthy, Antara will create automated touchpoints to keep them engaged and proactive. If they have or are at risk for a chronic condition, though, Antara’s Health Navigator will understand exactly where their mortality risk comes from, and can build a plan to lower their risk. Health Navigators can order lab tests and medications for home delivery, coordinate care, create personalized health plans, and check in regularly - all over texts, calls, and app-based messaging. Check out the product walkthrough:

Antara is working to scale Health Navigators to be able to take care of over 1,000 patients each. Over time, as the data gets better and the technology automates away more of the time-consuming, backend work like filling out forms, Health Navigators will be able to spend an increasing amount of time doing what humans do best: interacting with Members and guiding their care.

Engagement is key to Antara’s model. Data creates opportunities for engagement, engagement with a Health Navigator builds trust, and trust builds more opportunities to be the first port of call for healthcare. Engagement also lets Health Navigators rationalize care, which keeps patients healthier and prevents the onset of chronic diseases. More engagement creates more data, which allows Antara to continuously update a patient’s mortality score and risk factors, which kicks the loop back off. Instead of the vicious cycle so prevalent in emerging markets healthcare, Antara creates a virtuous cycle that looks something like this:

Through this process, Antara’s Health Navigators are able to triage and stay in touch with the most at-risk patients, and provide specific, actionable recommendations. Instead of “be more active,” they can say, “I know that you take the bus to work, and that you take this route. Instead of getting off at your office, try getting off two stops earlier and walking the rest of the way.”

Those little touches and the relationships that Members build with their Health Navigators mean that instead of being a financially-ruinous, worst-case-scenario nightmare, healthcare can become a delightful and normal part of Members’ lives.

That was Antara’s hypothesis when they set out on this journey in April 2019, and so far, the results are exceeding expectations.

Strong Early Traction

Antara is showing strong early signs of traction, and more importantly, validation that their model delivers the outcomes the team expected.

Today, Antara has 947 members, 100 that they signed up directly and 847 through a pilot with Kenya’s largest HMO, Avenue Healthcare. This no-fee pilot had one goal: to prove that the model works, for patients and insurers. The results point to a resounding YES.

To be successful, Antara will need to keep Members engaged, improve their health, and save payors (largely insurance companies and HMOs) money. They’ve checked all three boxes so far.

The impact Antara’s flywheel shows up in the results:

Members Are Engaged. 98% of members participated in the baseline consult and screening (versus 34% for Livongo in the US) and 60% of Antara members are active quarterly (compared to 13% annual utilization for Teladoc). Antara nearly 3x’ed the health plan baseline with a Net Promoter Score of 49, and 71% of October survey respondents said that they would be ‘Very Disappointed’ if they couldn’t use Antara. That’s product-market fit.

Improved Member Health. Engagement means more opportunities to catch and prevent chronic conditions. Specifically, Antara diagnosed 3x the chronic diseases in the population than were previously known, and drove down markers of hypertension and diabetes among members in the pilot (with better results on the latter than Livongo). They achieved these results through behavior change, largely without medication.

Lower Payor Costs. More engaged, healthier customers and Antara’s virtual delivery model brought down the payor’s average monthly cost by 23 to 43%.

Healthcare sounds complicated -- and when there’s a ton of red tape involved, it can be -- but it can be simple, and it goes back to the main question that Antara is solving for: Are we improving and extending their lives?

If a healthcare company can extend healthy lives, it has a good product. If it can convince payors to pay by providing cost savings, it has a business model.

Antara’s Business Model

Antara started out with a direct-to-member model, in which they sold to individuals or through small businesses and asked the member or their employer to pay. They quickly switched to a capitated model in which insurance companies pay a subscription fee per member per month.

Based on the results of the free pilot, Antara is on the goalline for a deal with a payor in which it would receive $5 per member per month. If signed, the deal would represent approximately $1 million in ARR. The company is also in talks with a number of leading pan-African insurers to sign similar deals.

For now, to grow quickly, collect data, improve the product, and continue to prove results, Antara’s virtual-first primary care services are available as an add on to health insurance plans. The best way to think about Antara’s business model is like a subscription business:

Acquire customers: Antara does this through partnerships with payors, meaning upfront sales costs but $0 marginal Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

Generate Monthly Revenue: Antara generates $5/member/month, paid by the insurance companies.

Keep Costs Low: To generate a positive contribution margin, Antara needs to serve each customer for less than $5 per month. To generate a profit, it needs to serve enough customers at a positive margin to cover fixed costs, like central team and technology.

To that end, Antara uses technology to supercharge staff Health Navigators: nurses, of whom there are many in Kenya at relatively low cost. By streamlining paperwork and automating repetitive tasks, and by focusing on those who need care while keeping healthy members on autopilot, Antara hopes to enable each Health Navigator to serve 1,000 Members.

Antara’s technology also powers staff virtual care doctors, enabling them to serve 50-70% of primary care cases directly through its Virtual MD service. Doctors are in lower supply in Kenya, but are still relatively affordable, particularly since Antara’s technology allows them to serve more Members.

Healthcare doesn’t have to be complicated. Antara’s unit economics look something like this:

Antara will be contribution margin positive from day one. Like any good technology company, with more Members, it will be able to improve the product, drive down marginal costs, improve margins, and cover fixed central costs with contribution margin.

Antara is building towards becoming an integral layer in the healthcare value chain with whom each and every insurer will need to partner in order to provide cheaper, better, and more convenient service. By partnering with Antara, insurers will improve top-line growth, because its differentiated and delightful product, combined with models that decrease underwriting risk, will make it possible to insure a much wider swath of the population and help close the 97% insurance gap in Kenya. Antara will improve their bottom lines, too, by decreasing the monthly cost to serve each Member and making Members healthier.

We talk about Lifetime Value (LTV) a lot here, and normally what we mean is: how long can we get this person or company to keep spending on our product? In the long-term, if Antara is successful, it will increase the LTV of each Member by actually extending their lives.

Over time, as Antara collects more data, improves its models, and drives better outcomes, it will create a product that powers continuous underwriting of insurance, meaning that it should be able to charge lower premiums by better understanding its customers, and intervening to improve outcomes. That, in turn, means it will be able to serve more Members, which will lead to better data and outcomes, and lower premiums. That is a flywheel.

Continuous underwriting is the future of insurance, but it’s currently difficult in markets like the US because of incumbent insurance providers and regulations. In emerging markets, there is more freedom to build the right way, practically from scratch, and insurers can work with Antara to make it a reality.

Ultimately, Antara’s Natively Integrated approach means it is building a product that combines the best parts of telehealth companies like Teladoc, chronic care management platforms like Livongo, and innovative insurers like HealthIQ to serve billions of people across emerging markets.

That’s an incredibly ambitious vision, but this scope is what is needed to bend incentives to achieve improved health outcomes at reduced cost. You can’t do it piecemeal; to solve such a massive problem takes a Natively Integrated approach.

Plus, if anyone can pull it off, it’s the Antara team.

The Antara Team

As you’ve no doubt realized by this point, building a Natively Integrated Healthcare Company to fix seemingly immovable emerging market health challenges by combining primary care, data, payor relationships, and Member engagement is very, very hard. There are not a lot of people in the world who could pull this off.

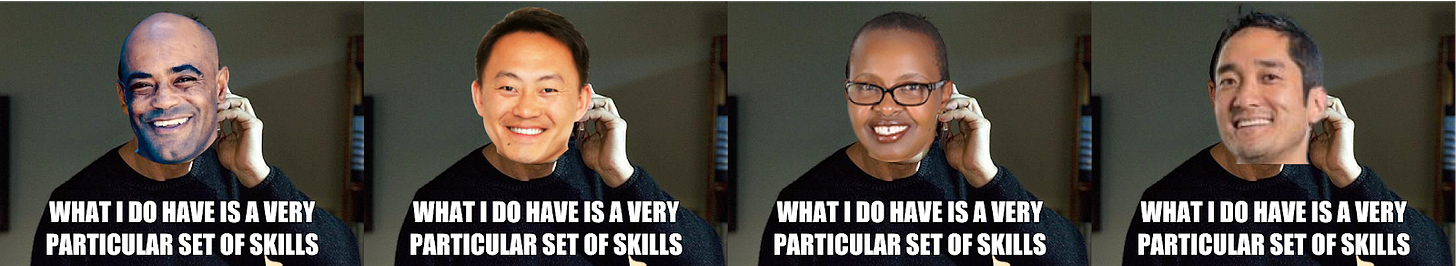

That’s why Antara’s team is the reason I’m most excited about the company. All four co-founders are exceptional, and each has clear ownership over an important piece of the business.

It’s hard to imagine a team better-constructed to tackle this particular problem with Antara’s particular solution.

KebbaJobarteh, Antara’s CEO, was born in Nairobi and grew up in NYC. When he was nine, he told his mom that he was going to go back to Africa and fix healthcare. Between then and now, Kebba went to Princeton, got his MD at Yale, and his MPH at Harvard. He has practiced as a pediatrician in Africa for fifteen years, in urban and rural areas, large and small. He’s built hospitals, clinics, and programs. He launched and ran Remit4Health, and serves on the Board of Directors for Partners in Health, the global healthcare non-profit launched by Paul Farmer.

Kuang Chen, Antara’s Tech lead, has spent his career using technology to improve healthcare and insurance. He turned his undergrad research into a company that does computational workflows for drug discovery, then he read Mountains Beyond Mountains, Tracy Kidder’s book about Paul Farmer, quit, and went to get his Ph.D in Computer Science at Berkeley. He built the world’s best handwriting recognition algorithm, and commercialized the tech in a company that sold into insurance and healthcare, which was acquired last year. In the process, he realized that insurance companies waste so much money, and that he could better align incentives -- so that insurance companies make more money when people live longer and healthier -- with technology.

Nthenya Mule, Antara’s Business lead, is the consummate healthcare operator, who has thrived in every aspect of healthcare that is not clinical. She helped set up Acumen’s East Africa Office and has served as the COO of a large healthcare service company, worked on the finance side of health and microfinance projects, and has a dedication and vision for healthcare that brings together the ambition of a start-up entrepreneur with the savvy of an operator.

Peter Park, Antara’s Product lead, was working in a wind farm after graduating from HBS when he, too, read Mountains Beyond Mountains and quit his job to work on global health. In 2011, Peter moved to Kenya to work in Health Financing and Operations at AMPATH, a non-profit working to “build holistic, sustainable health in Kenya and around the world.” In 2016, he left AMPATH to start ConnectHealth (YC F2), one of the first telemedicine companies in Africa.

The Antara co-founders are impressive on paper, but even more impressive off it. Check out this video to meet the team:

It seems like the kind of team that fate brought together, because it kind of is. Antara is the result of a chance coffee meeting in South Africa and the union of two teams working on two sides of the same problem.

In 2016, Peter founded ConnectHealth, a Y Combinator-backed company building telemedicine software for emerging markets. Two years later, in 2018, Kebba and Nthenya founded Remit4Health, which let members of the diaspora pay for healthcare for family back home, and pioneered the concept of Health Navigation to ensure that the money was spent on care that actually worked. When Peter and Kebba met up in late 2018, they realized that they were both trying to solve the same problem, each with one half of the solution. So Peter popped the question: “Why are we doing this separately?” They brought their respective teams together for a retreat, to see if they would gel, and according to Kebba, “It was incredible.”

During the two teams’ conversations about bringing together telemedicine and Health Navigation, they realized that they needed to use data science and automation to achieve their mission, but had no idea how to do it. Fortunately, a mutual AMPATH connection told Peter about this guy he knew who did machine learning research in east Africa, and just left years of doing automation and data science in insurance/healthcare. He was talking, of course, about Kuang. Turns out, Kuang was traveling the world with his family for the year and just so happened to be in Capetown at the same time as Kebba.

The two met up for coffee, and found they shared a common vision from two very different perspectives. Kuang called one of his best friends back in Berkeley who was also involved in Partners in Health for a backchannel, and serendipity struck again: Kebba was his boss in Malawi, and confirmed to be all-time-good-dude. Kuang cut his family’s circumnavigation six months short to launch Antara with Kebba, Nthenya and Peter.

The result of all of that serendipity is an Antara team bound together by each co-founder’s lifelong quest to use their particular skillset to improve healthcare.

I am fully confident that if anyone can figure out how to pull off virtual-first primary care in emerging markets, it’s the Antara team, but that doesn’t mean it’s without risks.

Risks

Early stage startups come with major risks, and Antara is no different. Here are a few Antara-specific risks:

Emerging Market. Emerging markets can be riskier than developed countries, particularly for investors less familiar with the particular market.

Different Languages and Cultures. Unlike China or India, where over 1 billion people speak the same language and share similar cultures, Africa’s 1.2 billion people live in fifty-four different countries, each with their own language (or many) and cultures. Scaling in Africa, and beyond, is more difficult than scaling in China.

Outcomes. Antara has achieved amazing early outcomes, but they may not replicate them at scale.

Regulation. The regulatory landscape can be challenging, unpredictable, and slow.

Business Model. Antara is early in testing its business model. There’s a chance that the discussions in which they’re currently involved don’t lead to a contract, and that insurers and HMOs are not willing to pay for Antara.

Competition. Competitors, whether new startups or incumbents, may copy or compete with Antara’s business.

There are certainly risks that neither I nor the Antara team is currently aware of that could sink the business. This is not investment advice.

Investing in Antara

Every startup involves risk. The question is whether the potential upside is worth it. And in this case, for me personally, I can’t think of a better shot to take. If Antara pulls this off, we’re not just talking about high ARR and strong margins; we’re talking about making millions of people healthier, happier, and more financially secure.

The beautiful thing about healthcare, when it works, is that you can do well by doing good. When Antara is successful, it will extend and improve the lives of millions of people. It will prevent those people from going bankrupt to pay for healthcare costs, and at the same time, it will save insurers money by making their customers healthier.

Antara, meanwhile, will generate margin on each Member whose life it improves as it continues to dramatically lower the cost to serve each Member. As the first call for people not used to calling their insurer or doctor at all, Antara will own the customer relationship and expand into adjacent, and potentially even more lucrative, opportunities. When it succeeds, Antara could be a multi-billion dollar company like its American counterparts, and a growing number of successful virtual care companies in China, India, and around the world.

I’m most excited about Antara’s potential to change healthcare for the better, but I’m also thrilled to invest in making that future a reality. We’re joined by top investors like Addition (Lee Fixel), Anorak (Greg Castle), A$AP Capital (Teachable founder Ankur Nagpal), Kepple Africa Ventures, Sage Hill, (and one more yet-to-be-announced Silicon Valley VC close to signing), alongside a roster of notable angels.

Thanks to Greg Castle for introducing me to Antara, to Dan for editing, and to Kebba, Kuang, and the Antara team for working with me on the memo and letting us come on this journey!

Enjoy your MLK Day, and I’ll talk to you on Thursday!

Thanks for reading,

Packy