Welcome to the 854 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! Join 81,328 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… On the Tape

If you like reading Not Boring, you'll love listening to On the Tape. Every Friday, CNBC Fast Money's Dan Nathan and Guy Adami, along with former hedge fund manager Danny Moses (of The Big Short fame) break down the biggest headlines impacting your money in the financial markets, demystifying the volatility in stocks, bonds, commodities, and of course, crypto. You'll leave with a nonconsensus perspective on financial markets and business news from three experienced voices whose goal is to provide listeners with the intellectual framework to think critically and make smarter investment decisions.

In each episode, the co-hosts go Off The Tape with a guest from the world of finance, media, or sports. Recent guests have been former "Top Cop of Wall Street" Preet Bharara, NFL Star and financial literacy activist Ndamukong Suh, CNBC's Melissa Lee, Meltem Demirors and Raoul Pal on crypto, and Yours Truly. I'm about to make my third appearance 👀 To stay smart about your money, subscribe and tune in on every Friday.

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Monday! I hope everyone had a great weekend and has their Halloween costumes squared away. I am supposedly going to be Aladdin. I have 6 days to get in vest-no-shirt shape. I’m ngmi.

In May 2020, a couple of months into the pandemic, I wrote my longest essay ever on a concept called scenius. Now, a year and a half later, we’re in the midst of a history-bending one.

Let’s get to it.

Sc3nius

We live in exceptionally rare times. We’re a part of the first global, internet-native Scenius.

Throughout history, a handful of time-place combinations have punched so far above their weight in terms of contribution to human progress that their existence befuddled academics.

In 1997, historian David Banks argued in “The Problem of Excess Genius” that, “The most important question we can ask of historians is ‘Why are some periods and places so astonishingly more productive than the rest?’"

Figure out why, the logic goes, and we should be able to reproduce those productive periods and places on-command. But in his essay, Banks concluded that no one had sufficiently explained the phenomenon, in part because “essentially no scholarly effort had been directed towards it.”

Twenty-three years later, Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison identified the same phenomenon in their 2020 essay, We Need a New Science of Progress:

Looking backwards, it’s striking how unevenly distributed progress has been in the past...the discoveries that came to elevate standards of living for everyone arose in comparatively tiny geographic pockets of innovative effort.

They called for a new scholarly discipline, Progress Studies, which “would study the successful people, organizations, institutions, policies, and cultures that have arisen to date, and it would attempt to concoct policies and prescriptions that would help improve our ability to generate useful progress in the future.”

The list of challenges facing humanity is long and complex: climate change, inequality, natural disasters, travel, education, and more. We can’t leave solving those hard problems to chance. Understanding those productive periods and places might give us insight into organizing ourselves in such a way as to maximize our chances of solving them.

The same periods come up over and over again in these conversations because they were so head-scratchingly productive. Ancient Greece. Renaissance Florence. Elizabethan England. Northern England during the Industrial Revolution. Silicon Valley. These time-place combinations produce new ideas, new art, new economic structures, and new technology of astonishing breadth, quality, and staying power.

Was it just random chance? Were an exceedingly large number of historical geniuses randomly born in the same small place in the same short timespan?

Across the pond, British ambient musician Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno RDI (henceforth, “Brian Eno”) was scratching at the same question, focusing less on scholarship and more on vibes. He sought to push back on “the notion that gifted individuals turn up out of nowhere and light the way for all the rest of us dummies to follow.”

In a letter to his friend Dave Stewart, published in his 1996 book A Year With Swollen Appendices, Eno wrote:

I became (and still am) more and more convinced that the important changes in cultural history were actually the product of very large numbers of people and circumstances conspiring to make something new. I call this ‘scenius’ - it means ‘the intelligence and intuition of a whole cultural scene’. It is the communal form of the concept of genius.

I would prefer to believe that the world is constantly being remade by all its inhabitants: that it is a cooperative enterprise.

In the letter, Eno cited cultural examples like Dadaism in France, American experimental music in the late 50’s and 60’s, and punk in the 70’s, but also suggested that it would be “interesting to include scenes that were less specifically artistic - for instance, the history of the evolution of the internet.”

Turns out, scenius shows up throughout history in those astonishingly productive places. It’s the best explanation I’ve seen for excess genius. According to Kevin Kelly, whose framework for scenius we’ll dive into shortly, “Scenius is like genius, only embedded in a scene rather than in genes.”

To clear up some terms we’ll use here, “scenius” is the concept of communal genius, but we’ll use Scenius with a capital S to describe those magical time-place combinations. Scenius is the proper noun; scenius is the common one. Ancient Greece was a Scenius. The Renaissance was a Scenius. Silicon Valley was a Scenius.

Historically, scenius had been tied to, and limited by, place. Early last year, pre-pandemic, I set out to write my longest essay to date on whether there could be an Internet Scenius that removed the physical boundaries and therefore unleashed more progress than any previous Scenius. There were about 100,000 people living in Florence during the Renaissance… if you multiply that by 79,000, do you get 79,000x the good ideas? Do you get even better ideas, thanks to more connections and better intellectual sparring?

I started research for the essay in February 2020, and quickly became disavowed of the notion. There were three reasons I didn’t think we’d been able to conjure Scenius online:

We have been unable to replicate the magical camaraderie of in-person collaboration online.

There has been no common mission or common enemy strong enough to unite people around the world (I see you, crypto people. We shall see.) [Ed. Note: I was ngmi]

Until now, we have not experienced a global catalyzing event that has necessitated new modes of creating, communicating, and collaborating.

Then, of course, COVID hit. COVID is the greatest catastrophe the world has experienced collectively since World War II, and it’s taken a terrible toll on human lives and the global economy. But I’m an optimist, and as I was writing Conjuring Scenius, I realized that it might also get us unstuck and create the conditions for an internet-scale scenius. Reading it back, a lot of the writing in the essay is cringey and overwrought, but I think I fucking nailed this prediction:

When it is all said and done, I believe that historians will look back at the Coronavirus pandemic as the greatest catalyst for progress and creativity in human history.

Seventeen months after I hit publish, we’re in the middle of a Holy Grail Scenius: global instead of local, with the internet as the scene, bound only by time but no longer by space. During COVID, we successfully moved large parts of the way we work and communicate online, unbound genius from geography, created new economic models and incentive structures, and made meaningful advances in healthcare, climate, finance, education, and more. This Scenius is also building the tools that will make other Scenia more common in the future.

Part of the reason that we’re more productive now than ever before is just that we’re on an exponential curve, following the Law of Accelerating Returns, as I covered in Compounding Crazy. But I think it’s something bigger than that, a step change instead of a smooth curve.

Since February, I’ve been writing an accidental series on how web3 is impacting culture, work, and the way that we all interact with each other. If Power to the Person was about how technology is empowering individuals as the new atomic units of commerce, The Great Online Game was about how the internet blurs the line between work and play for those individuals, and The Cooperation Economy was about how we play the game as teams of individuals or small groups, this essay goes one layer up to figure out how it all fits together: we’re all part of a great global Scenius. We’re all gonna make it. Let’s call it the WAGMI Scenius.

I had a vague idea that web3 was at the core of a new Scenius when I started researching this piece, but what I didn’t appreciate is that web3 seems to be a toolkit for conjuring Scenius. More than financial speculation, web3 offers a set of tools that can align incentives in ways that allow groups to tap into their communal genius. We’ll focus mainly on web3 in this piece because it fits the Scenius framework so beautifully, but the WAGMI Scenius isn’t limited to web3.

The conditions are ripe for progress, and the culture is coalescing around the same ethos that has defined Scenia of the past, but this time, the whole globe is participating. The outputs are unpredictable, but when all is said and done, I still believe historians will look back at this period as the most productive and creative in human history to date. Plus, the models we develop today might play a critical role in shaping how we govern our new frontiers: space and the Metaverse.

This essay is an attempt to put … gestures broadly at everything … into historical context and guess at where it’s headed. To understand what’s going on, why, how, and how to contribute, we’ll cover:

Deconstructing Scenius

Is This a Scenius?

WAGMI Scenius

Scenius is a vibe -- one of those, “you know it when you see it” things -- but there’s also a framework of exogenous and endogenous factors that nurture scenius and help us identify it.

Deconstructing Scenius

There are two sets of factors that make for a productive Scenius:

Exogenous factors are the pre-conditions, outside of the control of the scene itself.

Endogenous factors are those things the scene does and how it behaves, its rituals and norms.

The first part is luck -- whether the environment is right for Scenius at a given time -- and the second part is what the people in the scene do with that luck to make the most of the opportunity. Let’s start with the Exogenous.

Exogenous Factors

David Banks ended The Problem of Excess Genius with disappointment that so little, well, progress, had been made in understanding why intellectual hot spots appear on the map when and where they do.

Finally, fifteen years later, in a 2012 Wired article, Cultivating Genius, author Johah Lehrer proposed an answer to Banks’ question, citing Nobel Laureate Paul Romer’s work on meta-ideas, or ideas that support the spread of other ideas. He suggests three that have been present in eras of excess genius, like Renaissance Florence and Elizabethan England:

Human Mixing. Past talent clusters were all commercial trading centers, which allowed a diversity of people to share ideas.

Education. Each of the “flourishing cultures” Lehrer examined “pioneered new forms of teaching and learning.” In Florence, it was the rise of the apprentice-master model; in Elizabethan England, it was the government’s effort to educate middle-class males, like William Shakespeare, the son of an illiterate glover.

Institutions that Encourage Risk-Taking. Florence had the Medicis, and “Shakespeare was lucky to have royal support for his odd tragedies.” Wealthy benefactors gave creatives room to flourish. (This one sits between exogenous and endogenous).

In Conjuring Scenius, I tried to add some ingredients to the pot, and one in particular seemed to appear before most of history’s great Scenia: catastrophe.

Take a look:

Ancient Greece followed the Greek Dark Ages, a 350 year period after the collapse of the Bronze Age. You can draw a direct line from World War II to Building 20 at MIT, Bell Labs, and ultimately, Silicon Valley. The Junto came out of the Revolutionary War. The Renaissance emerged from the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Bubonic Plague. The two above that didn’t emerge from catastrophe rode the momentum from a previous Scenius and used its outputs as building blocks.

Why does Scenius emerge from catastrophe?

For one, catastrophe focuses energy, attention, and talent. The US Government pulled the brightest minds in the nation together to develop new technology to power the war effort, and those technologies, like the transistors that came out of Bell Labs, formed the foundation of Silicon Valley.

Second, crisis shakes and breaks and calls for new solutions. When everything is burnt to the ground, there’s room for new ideas and institutions to grow. Ben Franklin’s Junto created the first volunteer fire company, public library, and philosophical society in the young United States of America, along with the University of Pennsylvania.

Third, catastrophe brings people together in ways that are difficult to accomplish in peacetime. In Tribe, Sebastian Junger wrote:

Disasters, he proposed, create a “community of sufferers” that allows individuals to experience an immensely reassuring connection to others. As people come together to face an existential threat, Fritz found, class differences are temporarily erased, income disparities become irrelevant, race is overlooked, and individuals are assessed simply by what they are willing to do for the group.

Even after the catastrophe ends, there seems to be an afterglow, during which newly-formed channels of collaboration continue to bear fruit.

Those four factors -- human mixing, new educational models, institutions that encourage risk-taking, and catastrophe -- set the stage for Scenius. Then the endogenous factors take over, and it’s up to the scene to make its impact.

Endogenous Factors

A little over a decade after Brian Eno named and defined scenius, Wired’s Kevin Kelly popularized the term in the tech community and put a framework around it. In a 2008 blog post, Scenius, or Communal Genius, Kelly looked at some historical examples and came up with four factors that nurture scenius once it takes root:

Mutual appreciation: Risky moves are applauded by the group, subtlety is appreciated, and friendly competition goads the shy. Scenius can be thought of as the best of peer pressure.

Rapid exchange of tools and techniques: As soon as something is invented, it is flaunted and then shared. Ideas flow quickly because they are flowing inside a common language and sensibility.

Network effects of success: When a record is broken, a hit happens, or breakthrough erupts, the success is claimed by the entire scene. This empowers the scene to further success.

Local tolerance for the novelties: The local “outside” does not push back too hard against the transgressions of the scene. The renegades and mavericks are protected by this buffer zone.

Kelly’s four factors are present in any scenius, from the purely artistic to something as local and specific as Yosemite Park’s Camp 4. In Conjuring Scenius, I added four ingredients that seem to be present in all of the examples of the great Scenia that had a lasting impact on the world. One was emergence from catastrophe, described above, and the remaining three are endogenous factors that can be used to strengthen the Scenius:

Competition: Healthy competition sharpens the blades of new ideas within the safety of the scene, and pushes participants to achieve bigger and better things. The Ancient Greek philosophical schools competed in a “marketplace of ideas,” and competition between Michaelangelo and Leonardo (the artists, not the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles) raised the status of art in culture, and pushed both men to advance the craft.

Place-Based Ritual: A scene needs a setting. The Junto met in a bar, The Inklings in The Eagle and Child Pub, Motown’s artists in Detroit houses, and Renaissance artists in le botteghe. Informal meeting places enable all four of Kelly’s ingredients.

Diversity of Thought and Experience: New ideas form at the intersections of existing ones, and the mashup of people from diverse backgrounds, with diverse thoughts and experiences, provides fodder for the new. This is both an exogenous factor -- diverse people need to be in a certain place at a certain time for their ideas to mix -- and an endogenous one -- the scene needs to be welcoming to new people, ideas, and perspectives.

Those eleven factors -- four exogenous and seven endogenous -- can turn groups of individuals into a Scenius, a community that accomplishes much more, across a range of disciplines, than would otherwise be expected from a group of people with the same talents.

There have certainly been groupings of people as intelligent as those alive in Ancient Greece or Florence during the Renaissance who lived in the same place around the same time; without the right underlying conditions, however, they weren’t able to combine their talents in any way meaningful enough that we remember and build upon their contributions today.

When they are in place, though, magic happens. And they’re in place right now.

Is this a Scenius?

Individuals immersed in a productive scenius will blossom and produce their best work. When buoyed by scenius, you act like genius. Your like-minded peers, and the entire environment inspire you.

-- Kevin Kelly, Scenius, or Communal Genius

We’re in the middle of a new Scenius now, one global in scale and broad in scope. I can feel it. To put that feeling to the test, let’s run our current situation through those eleven factors.

Exogenous Factors

Scenia bloom in environments high in human mixing, new forms of education, institutions that encourage risk-taking, and ones that are emerging from catastrophe. That perfectly describes this moment in time.

Catastrophe

COVID is obviously the worst for many, many reasons... and it’s also been excellent for nurturing scenius.

It’s hard to remember, but two years ago, meeting people on Zoom was a bit of a novelty, Twitter friends were not real friends, and Discord was a chat room for gamers. Despite the fact that we had global connectivity, we hadn’t developed the cultural muscle memory to work together online as naturally as working in-person. Online meant lossy.

Then COVID changed everything. Within days, the world went from IRL to URL. Every single one of you has spent time on a Zoom happy hour, for better or worse, and more importantly, you’ve learned how to work with teams remotely, make friends on Twitter, play the Great Online Game, and team up in the Cooperation Economy. In the course of two years, we’ve become nearly as good, and in some cases better, at communicating, collaborating, and creating online as we were in-person.

It also gave people the chance to pursue the things that they were really interested in doing -- either instead of their old job, or on the side with no manager at their back. There would be no web3 renaissance without all of that time and attention seeking novelty and distraction online. We formed new habits that will outlast a return to normalcy.

Plus, COVID shocked the system and woke us back up. While people are still tribal, and there are plenty of idiots out there digging in deeper in counterproductive positions, most of us banded together around a shared mission. In Fritz’s parlance, we’re a “community of sufferers,” our differences temporarily erased and replaced by a hierarchy based on ability to contribute.

Human Mixing

If past clusters of genius were all local commercial trading centers, the internet is the world’s trading center. It’s hard to overstate or even understand the impact of pulling people from around the globe onto one big playing field.

In an interview with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Tyler Cowen said that, “the bringing together of different ideas and cultures and the new clash of opposing perspectives has been correlated with a lot of these Viennas [scenia] in world history.” Cowen pointed out that even in the Scottish Enlightenment, the immigration of people from the Scottish islands to Edinburgh was a bigger change than moving from “Mexico to Los Angeles today.” That human mixing created sparks that led to capitalism and a celebration of human reason, and we’re talking about going from the Scottish Isles to the mainland.

Now, anyone with an internet connection from Scotland to Mexico to Vietnam to Nigeria to India is able to build products that find global audiences and contribute to existing ones. They can be global creators and consumers.

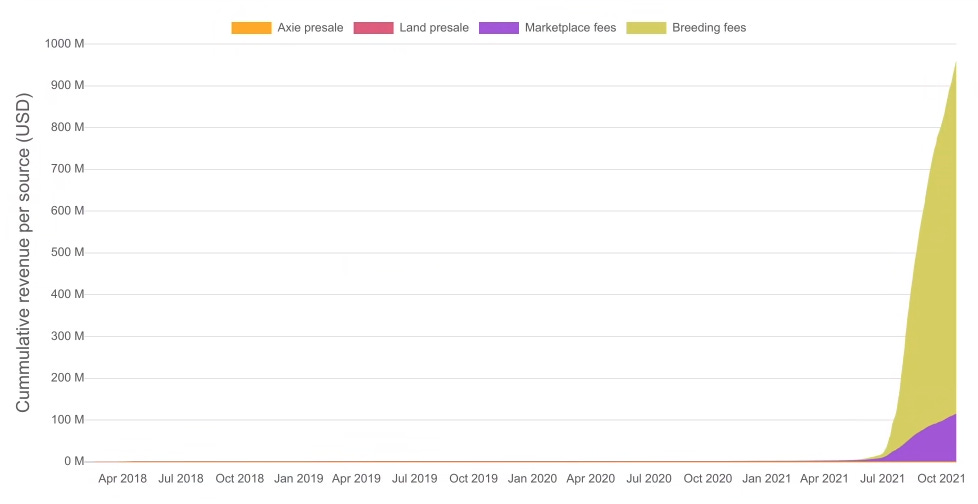

Friends with Benefits, the popular DAO with a $114 million market cap, has local channels for SF, Berlin, NYC, Asia & Australia, Miami, Canada, Lisbon, Paris, and more. Axie Infinity was started by a small team in Vietnam and is on track to do $1 billion in revenue, shake up the business model of gaming, launch the x-to-earn movement, and change employment in large countries from the Philippines to Brazil. Talent is evenly distributed, and opportunity is beginning to catch up.

Imagine the sparks that are going to fly as we get better at working together across borders. This global marketplace of talent and ideas might be the single biggest shift in the past half-century, and we’re just beginning to see the earliest implications.

Education

Another underappreciated impact of COVID is how dramatically it’s shaken up education.

That’s obvious on the surface -- millions of students shifted their education online for at least a year -- but there’s something bigger afoot. The sometimes tragically comical educational situations students found themselves in called the whole system into question. If our current educational system is largely a product of the Industrial Revolution, it’s about to be reshaped to fit our modern revolution.

The most important shift may be that credentials matter less than they have, and proving that you can do the work matters more. Between YouTube, Udemy, Replit, Optilistic, and a wide range of online educational resources, anyone smart and motivated enough can learn practically anything they want. They can participate in DAOs to get hands-on experience, and even earn while learning with products like RabbitHole.

It’s a callback to the apprenticeship model that helped shape the Renaissance in Florence, supercharged by giving students access to the world’s knowledge from their phone or laptop and the opportunity to experiment with different courses of self-directed study.

Less focus on credentials and more focus on doing the work means that the participants in a new scenius will potentially skew younger, infusing new creativity and energy into the scene, and blurring the lines between work and play.

Anish Agnihotri built PartyBid, for example, while a student at the University of Waterloo, and has more demand for his talents than any degree could bring him (he’s now an associate at crypto VC, Paradigm):

Institutions that Encourage Risk-Taking

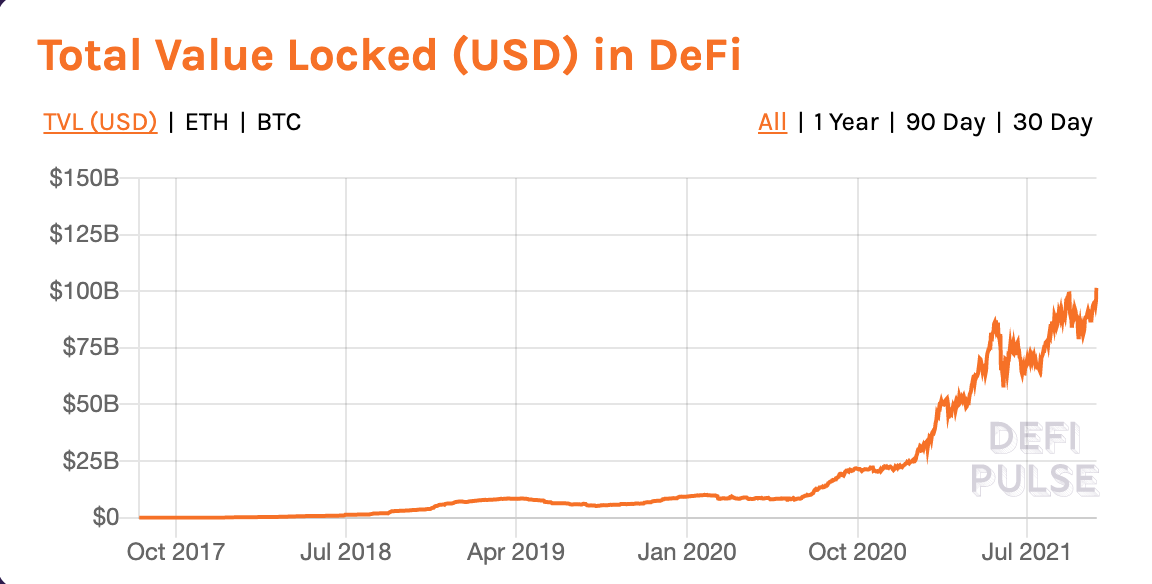

Florence had the Medicis. We have armies of well-funded VCs, institutions, and individuals clamoring for risk in search of yield. In this environment, any half-decent idea will get the money it needs to maximize its chances of success. In web3 specifically, my friend Rhys Lindmark points out that crypto VCs and hedge funds have $52.4 billion under management...

...that VCs have invested roughly 3x as much in crypto projects in 2021 as they did in 2020, and 5x what they invested in 2019…

… and that there’s 10x as much money locked in DeFi protocols, $100 billion, as there was in the beginning of the pandemic.

We are all Medicis. Shit, even Snoop Dogg revealed himself as pseudonymous NFT whale Cozomo de’ Medici:

There’s never been a better time to be a risk-taker. The cost of trying something new is less than zero; chances are, there are investors willing to give you a lot of money to do it.

So the scene is set. We’re comfortable collabor-ape-ing online, are less constrained by where we live and who we live near, have access to resources to learn anything and people to teach us, and operate in an environment in which financial institutions not only don’t discourage risk but actively covet it.

Getting all of those factors to line up is rare. Getting them to line up globally is rarer still. Are we taking advantage of our good fortune? Yes, yes we are.

Endogenous Factors

Once the conditions are in place, it’s up to the participants, all of us, to make scenius happen. While Kelly says that “Although many have tried many times, it is not really possible to command scenius into being,” there is a playbook for nurturing it once it’s in place.

The web3 community (aside from trolls and maxis) has been running that playbook to perfection, collectively, without realizing that that’s what they were doing. In fact, web3 seems perfectly suited as a model and set of tools to enable future scenia.

Mutual appreciation

Spend even an hour on Crypto Twitter and you’ll develop a sense of the power of mutual appreciation. Kelly wrote that mutual appreciation means that, “risky moves are applauded by the group, subtlety is appreciated, and friendly competition goads the shy.” Writing before Satoshi dropped the Bitcoin whitepaper, Kelly was describing the meme culture that now permeates web3.

When someone shares an NFT that they bought, others approvingly tell them it “looks rare.”

There’s a whole channel in the Wanderers Discord where Wanderers enthusiasts appreciate the subtle differences in each others’ NFTs.

Aping into new projects is applauded, and being early is often rewarded with airdrops, token grants to projects’ earliest supporters.

Friendly competition to build up unique NFT collections, earn the most yield, and contribute the most to DAOs encourages participation from even otherwise shy people, often hidden safely behind pseudonymous accounts and NFT pfps.

There’s never been a safer time to take risk, or such a large community welcoming risk-taking.

Rapid exchange of tools and techniques

This one is so on the nose it feels like I’m cheating. One of the core components of web3 is composability, the idea that pieces of software are lego blocks that builders can snap together to build new products, faster. As Chris Dixon wrote:

Examples of the impact of composability abound:

In a little over a year, we’ve moved from DeFi Summer to DeFi 2.0.

OlympusDAO, the poster child of DeFi 2.0, opened up its core tech and is licensing it to other protocols via Olympus Pro, which has already spawned projects like Klima DAO (on which more later).

Earlier this month, web3 publisher platform and so much more Mirror opened up its suite of tools, including Editions, Splits, Auctions, and its famed Token Race, to the public for anyone to build on top of.

Loot released lists of items as NFTs and allows anyone to build games and in-game items based on those lists.

The rise of DAOs has created an ecosystem of new projects, often led and funded by the DAOs themselves, building DAO tooling and easier ways for DAOs to collaborate.

NounsDAO, which is itself built on a fork of Compound Governance, opened up its intellectual property (the NFTs that it drops daily) under cc0, which gives up copyright and relinquishes control to the public domain, allowing projects like the ones that Jack Butcher describes in this thread:

The list goes on and on. And it’s not just software composability. The web3 ethos encourages open dialog, exchange, and education. As people learn, they share, and the scene’s knowledge compounds. My friend Dror Poleg is launching a hype-free crypto course to help onboard more people from the traditional business world. Station is building the infrastructure for people to find and participate in web3 projects. I’m part of the Crypto, Culture, and Society DAO, a crowdfunded learning DAO that seeks to solve the educational trilemma:

If successful, it will serve as a building block that others can use to create new educational experiences and accelerate the exchange of tools and techniques.

Network effects of success

Part of the magic of the Silicon Valley Scenius is that whenever a company has a good exit, that company’s founders, employees, and investors usually take their gains and invest in other startups. As good things happen for some, they help good things happen for others.

That happens on steroids in web3.

Cycles are shorter, people are getting rich faster, and they’re plowing their money back into new projects, mainly to make even more money, but often because they’ve quickly become the internet’s philanthropists and want to allocate resources to new art, culture, and governance that they want to see in the world.

Further, done right, tokens align incentives in such a way that network effects of success are baked in. That’s true on a local level -- a project’s builders and users do well when that project does well -- and on a more macro level. What’s good for the web3 ecosystem is often good for all of its participants, financially and emotionally. Even people who don’t own CryptoPunks celebrate when Punks sell for record prices; it means they were right about this whole NFT thing, after all.

If you need further proof, look no further than wagmi. Thousands of times per day, web3 folks tell each other wagmi across Twitter, Discords, Telegrams, and WhatsApp whenever anything remotely good happens. We’re all gonna make it is network effects of success in pure form.

Local tolerance for the novelties

Web3 is different than previous Scenia in a lot of ways, but maybe the biggest is that it began its life with money baked in. While other Scenia proposed radical new ideas, it was easier for them to hide away, for a while at least, and not draw authorities’ attention. Not so for web3.

China has banned crypto too many times to count at this point. Over the summer, US regulators proposed overly broad crypto legislation as part of the Infrastructure Bill that would cripple certain players, or at least force teams to set up shop overseas. When that happened, the whole community came out united and pushed back on the legislation; while the House still passed the bill, it showed that the most powerful players, and erstwhile competitors, are willing to fight together to protect the industry.

Earlier this month, a16z launched its web3 policy website and gave lawmakers a proposed policy agenda titled How to Win the Future: An Agenda for the Third Generation of the Internet.

In the face of obstacles, the biggest players in the space are putting their resources behind protecting the space’s novelty.

Competition

Web3 is cooperative, and it’s also competitive. It’s fueled by positive-sum competition in three main ways.

First, there’s the obvious: there is a global scoreboard running 24/7/365. While a continuous focus on the numbers can be unhealthy, it also means that projects are always competing with each other, or against their own records. If total value locked (TVL) in Saber were to drop, everyone would know about it immediately, and when the floor price of a popular NFT project drops, everyone knows about it.

Second, with users and contributors able to easily jump between projects, there’s a constant competition for the scarcest resource: attention. There are more great opportunities in crypto, openly accessible, than there is time in the day. Users’ assets are stored in their own, portable wallets, which they can take anywhere. There’s 24/7 liquidity. If one project is more exciting than another, or offers higher yields, people will jump.

Third, and most uniquely, there’s always the threat that a competitor, or even an unhappy community member, can fork your code and build a new, competitive version of the project. The most famous example of this is Chef Nomi, the pseudonymous team behind SushiSwap, forking Uniswap in a dispute over Uniswap’s resistance to issuing tokens to participants (Uniswap would later airdrop tokens to early users).

The threat that a competitor could copy-paste code and steal users, who can themselves bring all of their assets over since they live on the blockchain, and that all of this competition is out in the public, trackable on 24/7 scoreboards, means that teams need to constantly push to build better products and satisfy their users’ demands.

Place-Based Ritual

When I wrote Conjuring Scenius, this was the factor that I was most worried about, the one I thought would translate most poorly online. There’s no replacement for meeting in-person and grabbing a beer. But faced with no alternative, humans did what humans do: we adapted. We learned how to create ritual in online places.

The most clear example is gm. Every morning, across Twitter and in thousands of Discords, tens of thousands of people greet each other with a simple “gm,” short for good morning. Most of the Discords I’m in have dedicated “#gm” channels in which people wish each other gm all day, every day (remember, this is global, it’s always a good morning somewhere). There was even a short-lived gm app.

Each community has its own online rituals: AMAs, Town Halls, conversations that run non-stop across the globe. Twitter and Discord have become the bars and taverns of the WAGMI Scenius.

That said, place still has a place. Last week, thousands of web3 people went to Lisbon for LisCon, an Ethereum conference. Next week, they’ll be in NYC for NFT NYC. Then they’re back to Lisbon for Solana’s Breakpoint. As a dad who can’t travel as much, the amount of FOMO that I feel every other week speaks to the fact that the WAGMI Scenius has built place-based ritual that moves fluidly between online and IRL.

Diversity of Thought & Experience

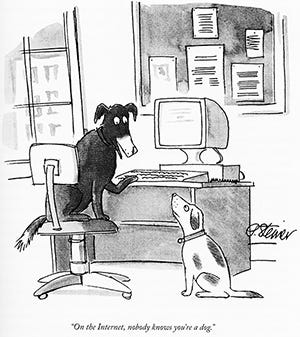

“On the internet, no one knows you’re a dog.”

In 1993, The New Yorker ran a Peter Steiner cartoon poking fun at the fact that people in internet chat rooms could use fake names and say whatever they wanted without revealing their true identity.

That worked for chat rooms, and as the internet evolved, people built followings on Twitter and built up karma in Reddit under pseudonyms, but until web3, it was impossible, or exceedingly difficult, to turn that clout into cash or to run a company pseudonymously. But pseudos are everywhere in web3; instead of a red flag, building up a following as a pseudonymous account is probably a signal that you know what you’re doing.

That levels the playing field. My friend Julia Lipton tweeted a few months ago about meeting the people behind some of those accounts:

Last week, I committed to invest in a protocol run by a really smart college kid who only identified himself by his pseudonym. Half of the investors in the round were pseudos who I’d seen on Twitter. And that made me feel more comfortable with the investment.

Combine that with the fact that web3 is global, open, and permissionless, and it means that there are more voices from more places mixing together and adding their contributions. The best ideas win, no matter who or where they come from, and those ideas are mashed up and remixed into more and more novel ideas. That’s contributed to an explosion of creativity in the space and will lead to enormous outcomes for the protocols and projects that embrace diverse participants.

Eleven factors, eleven checks. This is a Scenius, one that’s global, always-on, and ravenous for fresh ideas. So what’s the WAGMI Scenius up to?

WAGMI Scenius

After going through all eleven factors, it’s clear that the WAGMI Scenius is indeed a Scenius, and that it has all of the makings of those all-time impactful ones. In the moment, it feels bizarre to compare our lived experience to Ancient Greece or the Renaissance, but this has the potential to shape the next millennia like those have shaped history to this point.

Any great Scecnius is cross-disciplinary, and the WAGMI Scenius is no different.

Web3 is reshaping the internet, and putting ownership in the hands of the people who build and use it. Customer Acquisition Cost that would have gone to Google and Facebook is being redeployed as upside for participants. As we spend more and more time online, the significance of that will come to be fully appreciated.

In the next decade, let alone the next century and beyond, web3 will change how many people make a living. Already, Axie has 1.9 million users, many who rely on the game for their income, and has generated nearly $1 billion in revenue on nearly $2.5 billion in volume.

More play-to-earn games are coming, like Star Atlas and Wilder World, as are entrants to the broader category of “x-to-earn,” the set of projects that directly reward users for their attention and participation. For many, “work” will look a lot different, and more fun, in the next ten years.

It’s also reshaping arts and culture. More than half a million people have spent over $9 billion dollars on NFTs via OpenSea alone in the past three months.

In less than a month since announcing, Coinbase has over 2 million people on the waitlist for its NFT project. The corporates are coming. This is just getting started.

Those numbers are eye-popping, but they also mean that more artists are able to make a living selling their art and building communities around their work. As with the Medicis in Florence, more benefactors will mean that more artists can focus full-time on pushing the boundaries of their art. I’m particularly excited to see how the Wanderers universe evolves, and how the Aku story unfolds.

Aku is the story of a young black astronaut, created by former MLB player Micah Johnson after he heard his nephew ask, “Mom, can astronauts be black?” It’s done $10 million in volume, and Visa just announced that Micah will be its first sponsored artist.

NFTs are also paving the way for more digitally-native art, like the generative art scene, as seen in Art Blocks. Manifold lets creators put apps into their contracts, pushing NFTs beyond visual art.

Music NFTs are coming, too, and letting artists keep more of the money they generate instead of giving it to labels. The whole time I’ve been writing this piece, I’ve had Netsky on repeat on Audius, and new projects like Royal and Sound.xyz will push the boundaries of NFT music even further. If past Scenia are a guide, new models and benefactors won’t just mean a redistribution of profits, it will mean more musicians pushing the boundaries and creating new forms of music.

Web3 tools are also being used to help solve previously intractable problems, like climate change. Last week, Stew Bradley told me about Klima DAO, which is building a “black hole for carbon.”

Klima, built on top of Olympus Pro, incentivizes people to buy carbon offsets and lock them up, driving up the cost of the offsets, and therefore, of polluting. Klima launched last week and it’s already locked up nearly 6 million tons of carbon.

Already, its market cap its hovering around $1 billion, and participants are earning a 0.53% “rebase” every eight hours, which would compound to a ~32,000% APY. It’s a prime example of that Benjamin Franklin mantra of doing well by doing good, and an early example of leveraging web3 tools, norms, and money to incentivize and coordinate people to tackle the world’s biggest problems.

Klima is also a convenient literary bridge to use to point out that while we’ve focused on web3 because it so clearly fits the definition of Scenius, historians will obviously remember this Scenius for more than web3. In the next decade, we’re going to make leaps towards saving the planet, fixing healthcare and extending healthspans, changing the nature of work, traveling to space, and tackling myriad big problems. Many of the same exogenous and endogenous factors that contribute to web3’s flourishing are also present in those fields. Someone more embedded in those scenes should write about the amazing progress happening there; otherwise, I got some ‘sploring to do.

We live in fertile times, inside a testing ground for new economic and governance models. Web3 lets us run thousands of real-world experiments in economics, incentive design, and governance simultaneously, with tracking visible on-chain and open to all. We’re not going to replace democracy in the US with some new model that we discover in a Discord, but we’re pushing new frontiers, and those new frontiers will need new models.

In the next decade, we’ll have something that feels like a fully-functioning Metaverse, and many people will spend more of their time in these virtual worlds. They require new, open governance models and economic structures, and the experiments we’re running on web3 now will influence how those worlds run. The Ancient Greek Scenius gave us democracy, what models will the WAGMI Scenius give virtual works?

Beyond that, as space travel becomes more common and, ultimately, whether in 50 years, a century, or beyond, people will live off-earth, in space stations or on other planets far, far away. Those will have a clean economic and governmental slate, too, and they’ll need new models. It feels like a leap to draw a line from what we’re doing online today and how we’ll govern outer space, but don’t be surprised if your great great grandchildren live in a system influenced by the outputs of this Scenius.

So what should you do to contribute to the Scenius and help shape the future?

If you haven’t jumped in yet, as always, my advice is just to get involved and start learning, experimenting, participating, and building. Realize that things that might seem like novelties now, like tokens, NFTs, DAOs, and DeFi, are building blocks that future generations will build on, and that you have the potential to put your skills to work wherever they can do the most good.

If you’re already a part of the scene, realize that what you’re doing might have an impact far beyond this week, month, year, or even decade. Don’t get too serious, don’t crush the magic, but realize the magnitude of the opportunity and responsibility in front of you.

There are many roles to play in a Scenius -- from the Source who identifies the scene and expresses it, to the Charismatics who make it legible, the Artists who develop the palette and style of the scene, and even the Fans who bring the excitement and activation energy.

Scenius is kind of a silly word, but the exercise of zooming out and putting what we’re living through in the context of astonishingly productive periods in history is useful. With hindsight, I would have wanted to be a philosopher in Ancient Greece or an artist in Florence or an inventor during the Industrial Revolution.

This is one of those rare opportunities, with a difference: it’s open to anyone in the world with an internet connection. Get involved. We’re all gonna make it.

Thanks to Dan and Puja for editing!

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad

Thanks for reading and see you on Thursday,

Packy

I think this one finally put me down the rabbit hole...

2021 has been a historic year, and I finally feel like I'm an actor in it. Two moments:

1) getting vaccinated at Javits Center. Reminded me of WW2 rationing or women helping out in the factories.

2) witnessing web3 flourish everywhere. Similar to Enlightenment Paris, Renaissance Italy, early 20th century Detroit etc. Scenius. Love it. Read Edward Glaeser's "Triumph of the City" for another discussion on how

Loved reading every line of this!