Welcome to the 867 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since the last email! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, join 21,217 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

💙 We’re the #11 free newsletter on Substack. Like this email to help break the top 10!

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday! Short week, we got this.

If you told me even a year ago what I do for work today, I wouldn’t have believed you. To whit:

This week, I got to co-write an analysis of a Mexican beer, Coca-Cola bottling, and convenience store conglomerate with the brains behind a wildly popular pseudonymous Twitter account, Post Market, and send it out to over 21,000 people.

And I’m getting paid for it… by a company I wrote about in my analysis on Slack (which may or may not have moved the market) whose Director of Content I coincidentally included a picture of holding a “Hinkie Died for Your Sins” sign in my essay on Sam Hinkie three weeks ago.

And it all started with a tweet:

The internet, ladies and gentlemen…

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Crossbeam.

Crossbeam is the world's first and most powerful partner ecosystem platform. They act as a data escrow service that finds overlapping customers and prospects with your partners while keeping the rest of your data private and secure.

Crossbeam believes that the ecosystem economy will drive the growth of SaaS businesses. If your company uses partnerships to grow, you should map your accounts with Crossbeam, for free (!), today.

FEMSA: The Most Interesting Company in Mexico

A Post Market x Not Boring Collaboration

The C-Store Internet

In Mexico, the road to the Metaverse goes through a convenience store.

Fourteen million Mexican shoppers walk through OXXO’s doors each day to buy everything from a Coca-Cola to Fortnite V-Bucks.

OXXO is the on-ramp for the digital economy in Mexico. Over 60% of Mexico’s population is unbanked, and the Mexican economy is still largely cash-based. Instead of entering a credit card online, millions of shoppers go to the nearest OXXO to pay cash for over 5,000 digital services, from V-Bucks to Amazon to Netflix to electricity bills. Mexican consumers trust OXXO more than they trust the banks, as evidenced by the fact that OXXO’s Saldazo debit card is already the most popular in the country. That puts OXXO in the prime position to build the digital wallet for Mexico.

To a reader in a developed country, the idea that a convenience store (“c-store”) chain could become a fintech powerhouse sounds preposterous. It sounds even more loco when you learn that OXXO’s parent company, Fomento Económico Mexicano, S.A.B. de C.V. (FEMSA), is the 130-year-old descendent of a brewery, Cervecería Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma, founded by five families in Monterrey in 1890. But emerging markets afford opportunities for scope unrivaled in developed markets. When a country’s infrastructure is underdeveloped, the companies that build out the physical and digital logistics and distribution own unimpeachable channels through which they can push a wide range of products and services.

Digitally, WeChat, Gojek, Grab, and other Super Apps are essentially the internet in their respective home countries. Because they own the digital infrastructure, they’re able to build their own services on top or extract rent from the companies that do. FEMSA falls into a related category of companies that, by owning the customer relationship and habits due to physical proximity, may be able to expand into ownership of their digital transactions as well.

If it succeeds, FEMSA will be Mexico’s Super App.

FEMSA is to Mexico as Reliance is to India. Both are old companies, run by descendants of the founders, with histories of vertical integration and unmatched capabilities in distribution in economies that lack strong infrastructure, and a proven ability to push a variety of products through those distribution channels.

Where Reliance dominated polyester, petrochemicals, and refining in India, FEMSA built its empire on cerveza and Coca-Cola. When he took the reins of the family business, Reliance’s Mukesh Ambani’s first new venture was to launch Reliance Retail, which is now the largest retailer by stores in India. FEMSA’s Chairman and former CEO, Jose Antonio “Devil Fernández” Carbajal, took over his family company’s struggling OXXO subsidiary and grew it into the largest convenience store chain by number of stores in the Americas. And now, like Reliance did with Jio, FEMSA is using its legacy assets, and the cash flow they spit off, to build a digital growth engine that might transform the business, and the economy in its home country, yet again.

Today, FEMSA’s value comes from three main businesses: a 47% stake in the world’s largest Coca-Cola bottler, a 15% stake in brewer Heineken, and FEMSA Comercio, which runs pharmacies, gas stations, and most importantly, OXXO convenience stores throughout Mexico and Latin America.

Funds love c-stores. They’re the closest thing the physical world has to the internet. They’re easy to stand up, ubiquitous, offer high returns on capital, sell high-margin products like soft drinks, alcohol, salty snacks, and tobacco, and generate strong brand loyalty by becoming a part of their customers’ daily routine. I start every morning with Wawa, and until Amazon delivers $1 coffee within five minutes, that’s not going to change.

With COVID though, that physical ubiquity, typically a massive moat, became a liability. Mexico has been one of the hardest hit countries in the world, with mortality rates near 10%, and the government has enacted austerity measures instead of stimulus. While the country has largely avoided lockdowns, many people have opted to stay home, and same store sales across FEMSA’s properties have taken a hit.

As a result, FEMSA (NYSE: FMX) crashed from a pre-COVID high of $97.59 all the way to $53.50 in early November, before picking up after Biden’s victory (he’s expected to be friendlier to Mexico) and promising vaccine developments positioned FEMSA as a reopening trade.

Even after its recent move up, FEMSA’s core business is still undervalued and comes with a free option on Mexico’s Super App. Today, FEMSA is like 7-11, the Post Office, Coca-Cola, and Heineken all rolled into one. Tomorrow, if it’s able to fight through the COVID dip and accelerate its digital transformation, it could be all that plus M-Pesa or Gojek.

It will have to act quickly to make that happen. The Latin American digital wallet is a highly sought after prize, and COVID has handed digital-first competitors a drawbridge over its physical moat.

This isn’t FEMSA’s first rodeo, though. Devil Fernández told a Stanford GSB class in 2009:

Mexico has been a typical emerging country with all the typical problems that they have, which is every period of time, we have some kind of political or economic crisis. This (the financial crisis) is the first time the economic crisis wasn’t created by Mexicans!

COVID is the second. Each time FEMSA has faced disaster in its 130 year history -- from devaluation to financial crisis to murder -- it has reset and come back stronger.

The FEMSA Story

The FEMSA story is a cycle of vertical integration, diversification, and re-focusing, all under the guiding hand of its founding families.

In 1890, five men -- Isaac Garza, José Calderón, José A. Muguerza, Francisco G. Sada, and Joseph M. Schnaider -- founded the Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma Brewery in Monterrey, Mexico.

Quickly, the founding families established a governance structure that professionalized the business: one family runs the company and reports to the others as shareholders and board members.

In its first fifty years, the group vertically integrated:

1899: Built a glassworks Fábrica de Vidrios y Cristales to make their own bottles,

1921: Spun up their own bottle cap maker, Famosa,

1926: Established Empaques de Carton Titan, a packaging company,

1929: Established a distributor, Company Comercial Distribuidora

1936: Founded Malta S.A. to supply the malt needed to make the beer, and constituted all of the businesses into a holding company, VISA.

1942: Faced with steel shortages due to WWII, founded a steel mill, Hylsa, to manufacture the steel they needed for bottle caps.

Fifty years in, the small cerveceria was a fully vertically integrated operation. It even produced its own talent. In 1943, Chairman, Eugenio Garza Sada, built a university, Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, modeled after MIT.

“The Tec” is now a top three Mexican University and feeder to the company. Current FEMSA Chairman, Devil Fernández, studied and met his wife, herself the daughter of a former FEMSA Chairman, there.

This paragraph is not relevant to the story but.. In 1969, the geniuses in the bottling business invented a beer bottle that opens other beer bottles, and called them “opening bottles.” (Ed. Note: I cannot for the life of me fathom why every bottle doesn’t do this.)

Beyond genius bottles, the company continued to grow and expand, into synthetic fibers and chemicals, like a Mexican proto-Reliance. And like Reliance, two brothers, Eugenio and his brother Roberto, sat atop the company without a clear “supreme.” In this case, though, it wasn’t acrimonious, and the brothers decided to split the company in two in 1973:

ALFA, under Roberto, would take packaging, steel, fibers, and chemicals.

VISA, under Eugenio, would take the bank, Banca Serfín, and the brewery and the companies in its vertical development.

Tragically, that same year, a political group called Liga Communista 23 de Septiembre killed Eugenio in a failed kidnapping attempt, which the Echeverria government allegedly knew was coming. From here on out, we will follow his side of the company.

1978 was arguably FEMSA’s most important year in the past half-century. That year, VISA went public on the Mexican Stock Exchange and launched its first OXXO store in Monterrey.

Flush with cash at a time when diversification was en vogue thanks to the book In Search of Excellence, VISA levered up and went on a buying spree. Many of the acquisitions were ill-advised. Devil Fernández said that they got into car plastics, flowers, canned food, pizza, cheese (to vertically integrate the pizza), peanuts (to go with beer), Burger Boy (like a small Mexican McDonald’s), homebuilding, and what they called the “cold meat” business, or cemeteries 😬 They even entered into three fishing JVs, with the French, Spanish, and Japanese.

They did make one very smart move: buying the Mexico City Coca-Cola franchise from The Coca-Cola Company for $60 million.

In 1982, though, the government devalued the peso and crushed VISA, which was forced to sell off non-core businesses, including the bank. It even tried to sell its Coca-Cola franchise back to Coke for $22 million. When Coke came back at $19 million, VISA, offended, decided to keep it. That was fortuitous - its stake in the business is worth over $4 billion today.

The company, reconstituted as FEMSA in 1988, re-focused on its beverage businesses, which included Tecate as a result of a 1954 acquisition and Dos Equis and Sol after a 1985 merger. It held on to OXXO as well. Explaining the decision, Devil Fernández said, “50-60% of what we sell in OXXO are beverages. It gives us a lot of feedback from the customers.” In other words, OXXO is FEMSA’s version of the tight feedback loop with customers that modern DTC brands espouse.

When Devil Fernández joined the company in 1987 in the planning division, OXXO was an unloved money-loser with only 500 stores in a company that prided itself on making things. He told his boss, “This business has a lot of potential, it's a pity no one takes care of it,” to which his boss responded, “OK, you go run it then.”

Devil Fernández switched out the team, cut stores in half by dropping underperformers, set a goal of re-growing to 1,000 stores, and focused on OXXO as its own business instead of as the brewery’s ugly younger sibling.

Meanwhile, in 1993, in partnership with Coca-Cola, it spun out Coca-Cola FEMSA as a separate entity and sold shares on both the Mexican Stock Exchange and NYSE. It retained 47.2% of the business, a stake it still owns today.

The Devil became FEMSA’s CEO in 1995 and led the back half of a busy decade. "The Devil has a love affair with his two new babies, Coca-Cola and Oxxo," said Ernesto Canales, a Monterrey corporate lawyer.

In the first clue of FEMSA’s eventual tech ambitions, it had a wild late ‘90s and Y2K, listing its shares on the NASDAQ in 1998 and partnering with Oracle to create Solística.com, an internet based logistic services company, which somehow still operates today!

The next decade, from 2000 to 2010, was defined by acquisitions to expand its core beverage businesses. It bought Panamco, the largest Coca-Cola bottling operation in Latin America to become the second largest bottler in the Coca-Cola system worldwide, bought back the 30% stake in its breweries that it had sold to Labatt, and acquired the Brazilian brewery Kaiser.

In 2010, to further focus on his Coke and OXXO babies, Devil Fernández sold the beer business, FEMSA Cerveza, to Heineken in exchange for 20% of Heineken’s stock (it still owns 15%).

Over the past decade, the company has rapidly expanded its Comercio (especially OXXO) and Coca-Cola businesses. It’s acquired Coca-Cola bottling businesses in the Philippines, Brazil, Guatemala, and Uruguay, while opening over 1,000 OXXO stores per year and adding pharmacies into the mix via acquisitions in both Mexico and throughout Latin America.

In 2018, Devil Fernández retired as CEO (while retaining the Chairmanship) and handed the reins to Eduardo Padilla. Under Padilla, pre-COVID, FEMSA is showing worrying signs of repeating its early ‘80s “diworsifying” mistakes. In November 2019, it paid $750 million to acquire US-based wholesale B2B cash and carry company Jetro, and in March, it paid $900 million for Waxie, a seemingly random US janitorial supply company.

But like devaluation in 1982, COVID might provide a refocusing force. Already, Specialty’s, a Bay Area bakery that FEMSA acquired in 2016, shut down in May due to pandemic-induced closures. That should serve as a sign that FEMSA needs to focus on its core businesses, which are just now rebounding from COVID slowdowns, and expansion into its adjacent digital opportunity.

What is FEMSA Today?

Today, FEMSA is the third largest company in Mexico by market cap at $23.5 billion, behind only Walmart’s Mexico and Central American subsidiary, Walmex ($49.8 billion), and Carlos Slim’s telecom giant América Móvil ($47.0 bn). It employs 320,000 people in 13 countries.

FEMSA’s governance structure enables a long-term view. The families of the cerveceria’s five founders still own 39% of the company. Bill Gates, via his investment firm, Cascade, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is the company’s second largest shareholder with ~9% ownership. Cascade’s CIO, Michael Larson, sits on the board. He’s joined by Robert Denham, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s personal counsel and confidante. The combination of the family’s stewardship with patient capital like Gates’ means that FEMSA is able to take the longest view in the room. It means that a tragedy like COVID is a blip to FEMSA and not an existential crisis.

When asked how FEMSA was handling the financial crisis, swine flu, and drug wars in 2009, Devil Fernández responded:

One of the advantages of family ownership is that the long-term view is there. We are not thinking or worried about next quarter’s numbers. Never. If you asked me how they’re going to be, I don’t know and I don’t care, because we see the long-term potential of the company. We are always making decisions that will influence the numbers in the future, not the next quarter.

Thanks to Devil Fernández’s priorities as CEO, and now as Chairman, the future of the company is beverages and OXXO. What was once a sprawling collection of companies in various quasi-tangential businesses is now cleanly organized into three units.

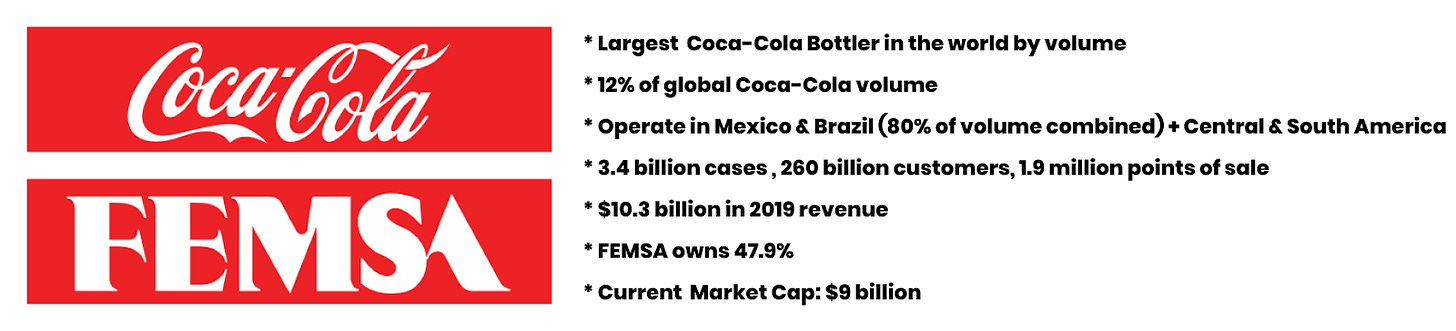

Coca-Cola FEMSA. FEMSA owns 47.2% of the largest Coca-Cola bottler in the world.

Heineken. FEMSA acquired a 15% ownership stake of Heineken in exchange for its beer businesses, which included Sol, Tecate, and Dos Equis.

FEMSA Comercio. OXXO, which falls under Comercio, is the crown jewel of FEMSA’s holdings. It operates over 20,000 c-stores, more than anyone else in the Americas. FEMSA also operates its Health and Fuel divisions under the Comercio business unit.

A fourth unit, Strategic Businesses, mainly serves its other business units with logistics (Solistica!), point-of-sale refrigeration, and plastics.

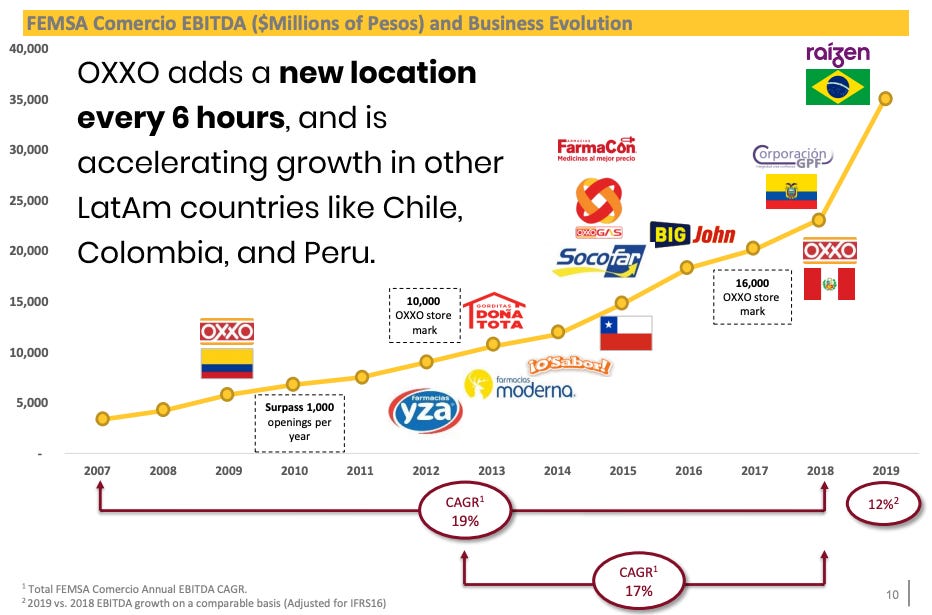

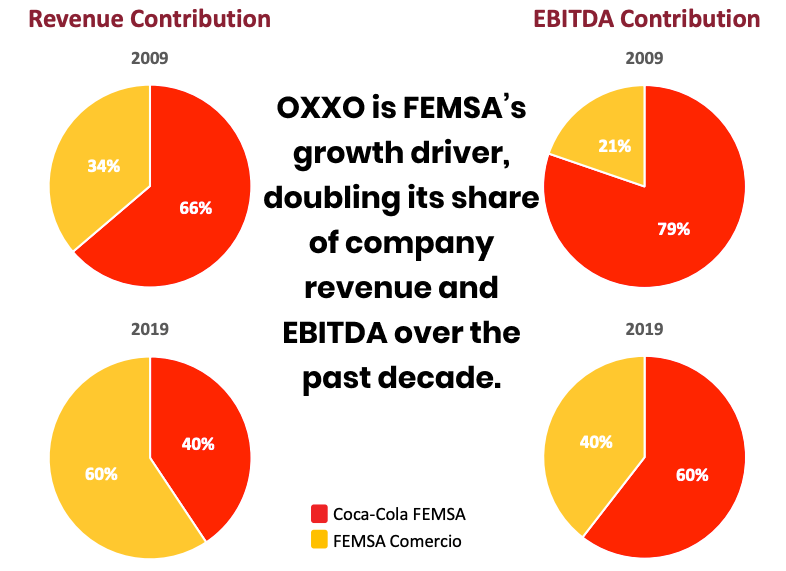

Comercio, and OXXO specifically, is increasingly important to FEMSA’s present and future. It has nearly doubled its share of FEMSA’s revenue and EBITDA over the past decade, and its 20,000-strong network of small-format stores is the company’s most important strategic asset.

The business units work together. Beer money funded the launch of OXXO and the expansion into Coca-Cola bottling, and OXXO now provides distribution and customer touchpoints for Heineken’s beers and Coca-Cola’s beverages, which spit off cash the company can use to expand OXXO and push into digital services.

Breaking apart the three core businesses highlights that despite the synergies, FEMSA trades at a conglomerate discount to the sum of its parts, before even accounting for its digital upside.

FEMSA’s Business Units by the Numbers

Coca-Cola FEMSA

If you wanted to “Buy the world a Coke,” you’d need to actually purchase those Cokes from its 225 bottling partners worldwide. Coca-Cola doesn’t make, bottle, and distribute its own product. Instead, it has a series of contractual relationships with Coca-Cola bottlers throughout the world. Coca-Cola owns a portfolio of brands and their formulations, and sells the bottlers concentrates of its beverages. The bottlers add water, fizz, and packaging, and then sell the finished product in their markets.

Coca-Cola is wildly popular in LatAm, with 5-15x the market share of its closest competitors. Coca-Cola FEMSA (“KOF”), with operations in Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, the Philippines, and other Central American countries, is the largest Coca-Cola bottler by volume in the world. In 2019, it generated $10.3 billion in revenue by serving 3.4 billion cases of Coca-Cola beverages to 260 million customers at 1.9 million locations. That represented 12% of Coca-Cola’s global volume.

Distributing Coke products in Mexico is very different than distributing them in the US. Mexico City has more retailers by number than all of the United States, but drop sizes, which run from 200-400 cases per week in the US, are closer to 2 cases per week in Mexico. That requires a very different set of competencies.

Because of KOF’s scale, unique capabilities, and contractual relationship with Coca-Cola, it is able to approach the partnership as an equal. For example, Devil Fernández has spoken about the importance of dictating the price at which it sells Coca-Cola products instead of allowing Coca-Cola to make that decision.

KOF’s strategic and financial importance to FEMSA comes from its steady growth and the cash it generates. It’s grown revenue at a 7% CAGR and Free Cash Flow at 10% over the past decade. Even through COVID, FCF remained relatively flat, and KOF continues to throw off cash that FEMSA can spend to expand Comercio and push into digital services.

Heineken

In 2010, FEMSA sold its breweries, including popular brands like Dos Equis, Sol, and Tecate, to Heineken, in exchange for 20% of the premium Dutch brewer. (FEMSA currently owns 15%.)

The Heineken stake has been good to FEMSA -- it has grown at around a 10% CAGR for the past decade. Heineken has invested heavily in emerging markets, specifically Africa and China, where it signed a partnership in 2018 with China Resources Enterprise, giving it a 20% stake in the country’s market leader and brewer of its most popular beer, Snow.

Prior to COVID, Heineken reported its strongest period of growth in over a decade, led by double-digit growth in the Heineken brand in emerging markets, including Mexico. But it will face headwinds in Mexico moving forward.

This year, a ten-year exclusive agreement with Heineken is set to expire, and OXXO entered into an agreement with AB Inbev to begin selling its Modelo brands, including Corona, the most popular in Mexico. While it will continue to sell the beers that Heineken acquired from FEMSA, the relationship is less important now and Heineken will take a hit by losing the OXXO exclusive in one of its biggest markets. We wouldn’t be surprised to see FEMSA sell its 15% stake in Heineken now that the stock is rebounding and approaching all-time highs. That would generate roughly $8.5 billion that the company could put towards FEMSA Comercio and the digital transformation.

FEMSA Comercio

FEMSA Comercio, which includes Health, Fuel, and most importantly, Proximity ( mainly OXXO), is FEMSA’s growth engine. Since Devil Fernández took over its operations in the late 1980s, FEMSA has grown from ~500 stores to 20,000, dwarfing its nearest rival 7-Eleven with nearly 10x the number of stores in Mexico and almost twice as many in the Americas.

OXXO stores are margin machines. They’re small, about 100m2 each, cheap and easy to build out, and sell high-velocity, high-margin products like chips, tobacco, and beer. As OXXO continues to expand into digital services, of which it currently offers over 5,000, its margins will benefit from their near-100% margins. As a result, OXXO stores generate an annual after-tax Return on Invested Capital of ~30%.

In 2019, OXXO did $9.4 billion in revenue, but revenue is down 3.8% YoY for the first nine months due to COVID. When COVID passes, there are two big non-digital growth drivers around the corner:

Continued Expansion. The company sees the potential for 30,000 stores in Mexico alone, with additional expansion in other Latin American markets.

Corona. No, not the virus. That’s bad for growth. But OXXO will soon begin selling Corona, Mexico’s most popular beer, with a rollout to all stores expected by 2022.

In addition to Proximity, FEMSA Comercio started its Health Division in 2012, and has grown through acquisition and expansion to become the 2nd largest pharmacy chain in Latin America, with nearly 3,200 points of sale. In 2019, FEMSA added 800 new pharmacies, its biggest growth year to date, and the timing couldn’t have been better.

Due to COVID, Health is the only division within FEMSA that has grown revenue YOY. First nine months revenue grew from $2.2 billion in 2019 to $2.4 billion in 2020, despite mobility restrictions that limited otherwise strong demand.

The Fuel division, which was made possible by the country’s denationalization of state-run Pemex, operates 545 service stations out of approximately 12,500 in the country. After adding 87 stations in 2018, Fuel added only six in 2019, another bit of fortuitous timing as Fuel was the hardest-hit Comercio business, down 27.5% to $1.3 billion in revenue in the first nine months of 2019.

Undervalued at Less Than The Sum of Its Parts

Looking at each of FEMSA’s business lines separately exposes deep undervaluation.

This year, FEMSA has materially underperformed both the Bolsa Mexicana de Valores (“Mexbol”) and its own components (KOF & Heineken). At its trough valuation, the FEMSA “stub” (FEMSA market cap minus the value of its stake in Heineken and Coca-Cola FEMSA) traded at a value of $7.5b or <6.0x EBITDA. For context, Walmex, the largest retailer in the region, has historically traded at 14.0x EBITDA. FEMSA is arguably a better business, and is inarguably growing faster than Walmex (ex-COVID), and it’s trading at half price.

Further, if you reduce the valuation by the $1.7b of investments made in the U.S. ($900M for WAXIE in March 2020 and $750M for Jetro in November 2019) the implied value of the Femsa Comercio business was a meager ~$6 billion. Since its November lows the implied valuation has recovered to $11.5b for the Comercio division ($10b excluding the recent U.S. distribution acquisitions). Of note, the valuation dislocation persisted until November, well past the market lows of March 2020.

While ‘Sum-of-the-Parts’ discounts are worthless without a catalyst to close them, there is reason to believe that FEMSA will monetize its Heineken stake in the coming year. At its current market value, it could monetize its interest in Heineken for ~$8.5b. FEMSA’s ‘conglomerate discount’ has seemingly been exacerbated by the expiration of their lock-up on the Heineken stake (which expired in late 2015), but parking $1.6 billion of cash in cash-and-carry and janitorial distribution in the U.S. has done little to assuage investor concerns around capital allocation. Latin American ECM bankers are salivating at the opportunity to lead the spin-off of OXXO, which would undoubtedly unlock material value; but thus far the family has resisted any approaches. Beginning next year, FEMSA will disclose with a P&L for both the legacy logistics business, which is called Solistica and the acquired Jan-San business, which will further highlight the strength of the crown-jewel OXXO business.

FEMSA’s current business is undervalued, and that’s before even taking OXXO’s potential digital transformation into account.

OXXO’s Strategic Importance

When BlackBerry founder Mike Laziridis first introduced the term “Super App” in his 2010 Mobile World Congress address, he said:

This is what we mean when we talk about super apps: creating experiences that are so seamless to use, that are so well integrated with the core applications that they become a natural part of your daily interactions.

He was talking about BlackBerry as the Super App, which, lol, but the point stands: Super Apps offer convenience. They’re the one, easy-to-access place where you can get most of the things you need every day. In that sense, OXXO is already Mexico’s Super App.

“Convenience store” is one of those phrases that’s so commonly used that it loses its original meaning. But the convenience of the convenience store allows them to grow while much of brick and mortar retail struggles in the face of Amazon and eCommerce more broadly.

OXXO’s 19,000+ locations in Mexico mean that an OXXO is never far away. In fact, in most of the regions in which it operates, there’s more than one OXXO for every 10,000 people, and those OXXO’s have the things people want every day -- chips, cigarettes, beer, soda, and water.

Taken together, that means that Mexicans go to OXXO often. Every day, 14 million, or more than 1 in 10 Mexicans, shop in an OXXO. An average of 735 people frequent each small OXXO per day, and most multiple times per week. When the OXXO is only two minutes away, people can visit OXXO more conveniently and frequently than they visit most websites.

All of those customer touch points serve to build trust with, knowledge of, and proximity to customers, which OXXO has leveraged to expand its offerings. For example, OXXO introduced the Saldazo debit card in 2012, and it has issued over 14 million cards since. The advantage is in the name of the business unit in which OXXO sits: Proximity. With 19,000 OXXO stores and an additional 1,250 pharmacies and 545 gas stations, FEMSA has 50% more retail locations than there are combined bank branches in the country (13,000). If you’re going to the OXXO to pick up beer anyway, why not deposit the cash you earned that day?

FEMSA’s Head of Investor Relations, Juan Fonseca, told the WSJ, “This is the first banking relationship for most of the users of this product,” adding that while the cards don’t generate much revenue from fees, they do generate data that helps OXXO tailor in-store promotions. Launching a low-fee debit card to collect data is a move that only a well-funded, ubiquitous, trusted brand with a long-term focus could pull off. Beyond data, it established a new behavior in customers -- paying cash to OXXO for something other than a physical item right now -- that laid the groundwork for digital payments.

In 2016, FEMSA invested in payment startup Conekta’s Series A, and partnered with the company to let customers pay cash for more than 5,000 digital services in-store. In a country in which 60% of the people don’t have a bank account, OXXO is their “Pay Now” button. For those without a credit card, OXXO is where they go to pay for their Netflix or Spotify subscription, pay their electricity bill, or buy Fortnite V-Bucks. Stripe accepts cash payments made in OXXO stores, meaning that any company that uses Stripe for payments can sell its products via OXXO.

Like a digital Super App, OXXO puts everything customers need to buy in one place. OXXO even works with most retailers’ biggest enemy: Amazon.

Whereas Amazon has crushed most retailers, c-stores are worthy adversaries because their frequent, low average order value purchases are difficult for eCommerce companies to serve economically. Plus, in a country in which home delivery is often difficult or even dangerous, OXXO serves as a network of Amazon pickup points close to customers. Add in the fact that unbanked customers can’t pay for Amazon products without a cash payment option, and Amazon has no choice but to work with OXXO.

“Mexico runs on cash,” Enrique Culebro, head of Mexico’s internet association, told Reuters. “This is the huge advantage of a company like Oxxo.”

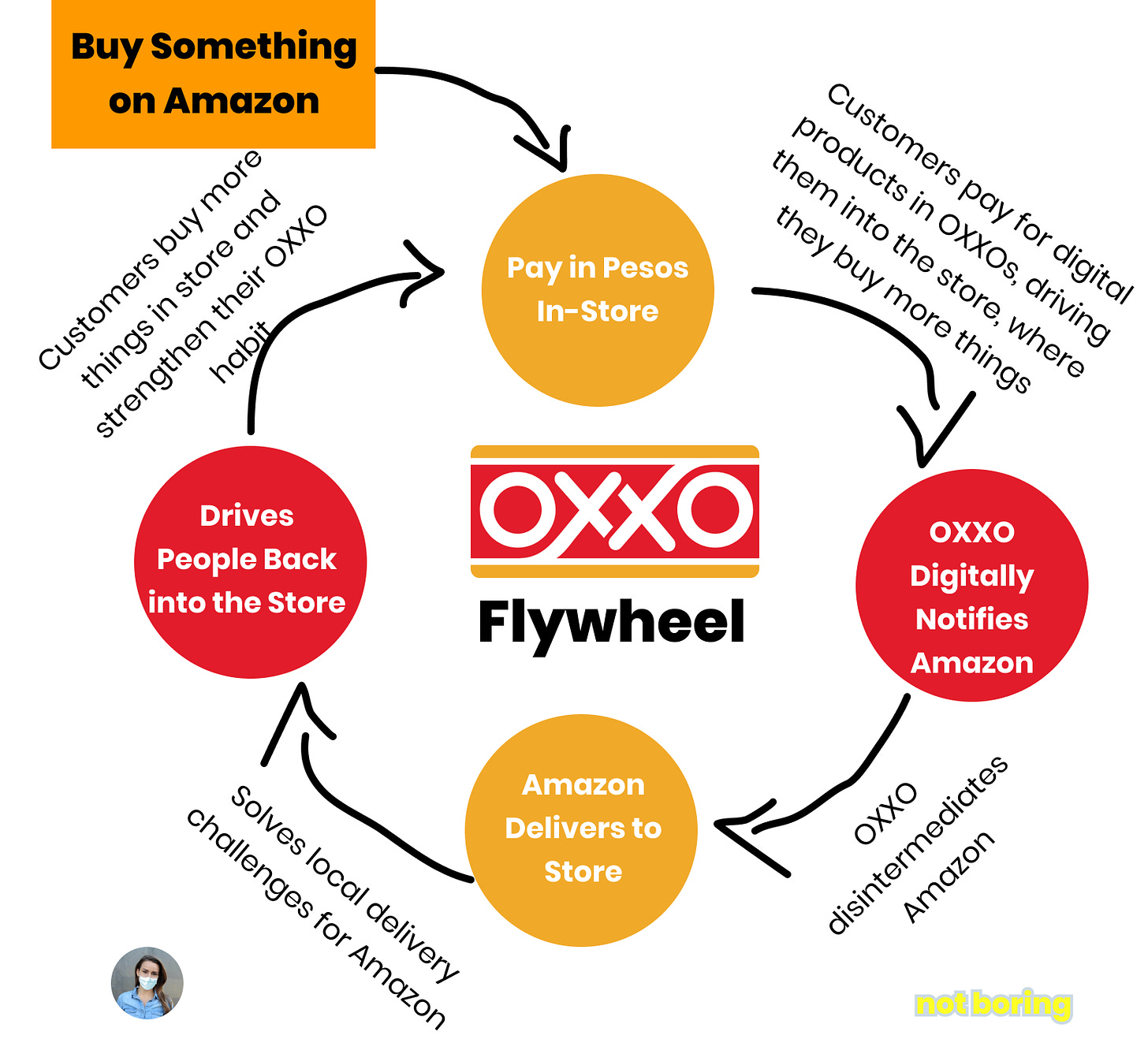

OXXO’s relationship with Amazon and other eCommerce businesses creates this beautiful flywheel:

This same flywheel holds for any digital purchase of a physical product. Customers need to come to OXXO at least twice per transaction, where they buy things (good for revenue short-term) and build more brand loyalty and trust with OXXO, which enables OXXO to push more products and services like debit cards and digital wallets.

By sitting at a crucial point in the value chain, between customers and everything that they want to buy online, OXXO generates revenue from both sides. OXXO Pay’s pricing power evinces its importance to both retailers and customers: retailers pay OXXO 3.5% per transaction and customers pay 10 pesos. That place in the value chain is why OXXO will be able to successfully build a digital wallet.

OXXO’s Digital Wallet and Super App Ambitions

Digital wallets -- apps like PayPal, Apple Pay, Venmo, AliPay, Mercado Pago, and M-Pesa that allow people to store money digitally and pay online and in-person -- are a huge and growing market. Since 2017, the market has nearly tripled from $368 million to $1 trillion in 2020.

They’re also extremely hard to build, because they’re essentially marketplaces. Success requires liquidity -- there need to be enough retailers that accept the wallet that it’s valuable for customers, and enough customers who use it that it’s valuable for retailers.

This is OXXO’s moat: it already has 14 million DAUs and 5,000 supplier relationships, including massive ones like Amazon and Stripe that provide ample supply liquidity. It’s also proven its ability to expand from traditional c-store retail to Saldazo debit cards to OXXO Pay.

By owning Mexico’s digital wallet, OXXO will:

Own the consumer financial infrastructure in the world’s fifteenth largest economy, with the potential to expand throughout Latin America.

Build lending products based on customer transaction history, giving people who previously had no access to credit new opportunities.

Facilitate and participate in the growth of Mexican eCommerce.

Further cement its place in customers’ lives, both online and offline, as the only viable omni-channel solution.

Building the digital wallet is a multi-billion opportunity in its own right. But it also means grabbing the lead position to add more services and build the leading Mexican, and potentially Latin American, SuperApp. Latin America is fertile ground for Super Apps because of its underdeveloped infrastructure and unbanked population. It’s less like the United States, which may be past the point of Super Apps, and more like Asia, where multiple Super Apps sit at the heart of multi-billion dollar companies.

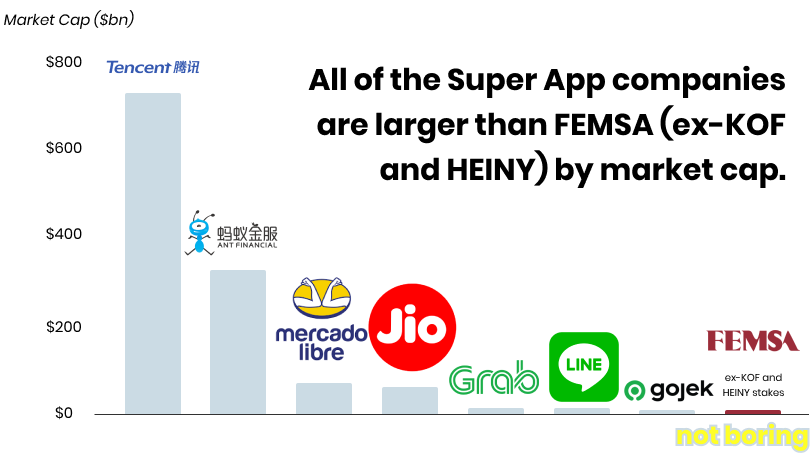

Indonesia’s Gojek is valued at $10 billion, nearly half of FEMSA’s valuation and more than FEMSA’s stub ex-Coca-Cola and Heineken stakes. Indonesia’s GDP is nearly 20% lower than Mexico’s. Gojek is backed by Chinese giant Tencent, whose own Super App, WeChat, is the key to its $726 billion valuation. Also in China, Alibaba spin-off Ant Financial’s digital wallet/SuperApp, Alipay, was preparing to go public at a market cap north of $300 billion before the Chinese government scuttled its plan. That’s over $1 trillion in market cap driven by Super Apps, in just one country.

And then there’s India, where Reliance raised over $20 billion for Jio at a $60 billion valuation, including $5.7 billion from Facebook, in part to grease the wheels for WhatsApp to become the Super App there. Earlier this month, it began rolling out WhatsApp Pay, a big step towards realizing that vision, and confirmation that in emerging markets, partnering, instead of competing, with the local powerhouse is smart business.

There’s a long way to go between where OXXO Pay is today and what even Gojek, Grab, or Line offer, and the larger Super App companies like Tencent, Ant, Mercado Libre, and Jio are a lot more than a Super App, but those companies success show the bull case for FEMSA. Given that the core business is already undervalued, OXXO’s strategic position in the value chain means that investors have a free option on a $10+ billion opportunity.

COVID-Accelerated Risks

Building the winning Super App would be massively valuable to FEMSA. You didn’t think it would be easy, did you?

While COVID created a buying opportunity by tanking FEMSA’s stock price, it also legitimately put a damper on FEMSA’s growth, exacerbating existing political and competitive threats to the business. There are two main categories of risk:

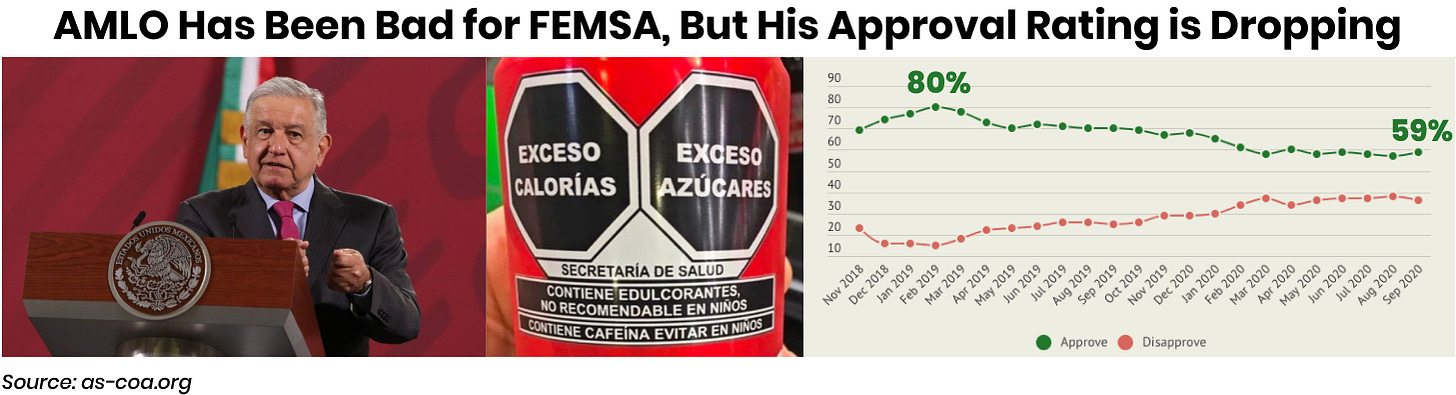

Political. Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (“AMLO”) has proven unfriendly to big business and openly opposes FEMSA in a few key areas.

Competitive. COVID pushed more transactions online, providing a boost to competitors like Rappi and Mercado Libre.

Political

AMLO is bad for business. The President mishandled COVID -- its 9.8% mortality rate is among the highest in the world, and instead of providing stimulus, the government implemented austerity measures. Of specific concern, AMLO’s government blames Coca-Cola for the country’s high mortality rate. More Coke = more obesity and diabetes = higher COVID mortality rates. In October, the government imposed regulations that will force Coca-Cola to put big octagonal black warning labels on its products by December 1st.

That’s bad news for FEMSA’s cash cow. AMLO hit FEMSA’s cash more directly in May, when the company agreed to pay $398 million in taxes to “resolve interpretive differences over taxes paid outside of Mexico.” Walmex also agreed to pay $358 million.

But there’s hope for FEMSA. From a pre-COVID high of 80%, AMLO’s approval rating has dropped to 59%.

Finally, as is often the case with emerging market investments, investing in Mexico comes with significant currency risk. Between February and April, the Mexican Peso / US Dollar exchange rate shot up from $18.54 to $24.99, and the government has intentionally devalued its currency multiple times in recent history.

Competitive

Challenges with government and currency are nothing new to FEMSA. Recall that the 1982 devaluation forced the company to shed non-core businesses to service debt, which left it in a healthier position. The bigger threat to the business comes indirectly from COVID.

As it has around the world, COVID accelerated the growth of eCommerce in Mexico and Latin America. While nothing beats the speed and convenience of paying cash at the local OXXO, many customers were forced to adopt alternatives during restrictions. Essentially, COVID jammed OXXO’s Flywheel, and opened the door for pure-play eCommerce competitors.

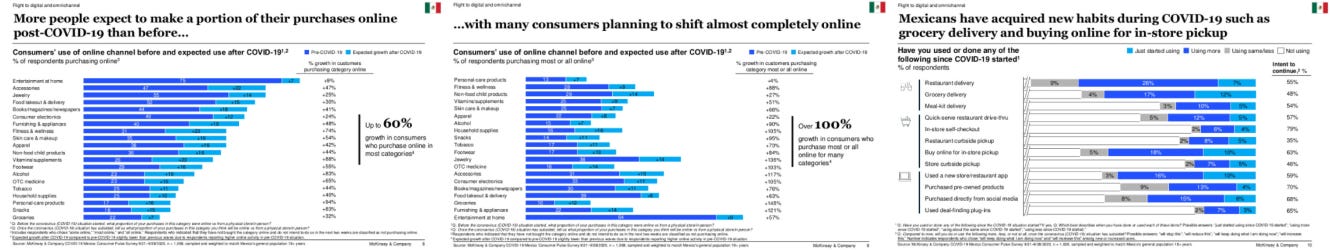

These three slides from a recent McKinsey presentation on Mexican consumer sentiment during COVID present both opportunities and threats to FEMSA, depending on how consumers are transacting online:

McKinsey notes a shift to digital and omnichannel. If consumers are going to OXXO to pay cash for digital services, that should present a short-term boost to margins and an even stronger opening for OXXO to push its digital wallet. Customers don’t want to go to the store every time they need to pay for something online during COVID, so funding a digital wallet once and being able to pay for anything online is a valuable offering.

But less frequent trips to the OXXO jam the flywheel. If people aren’t running out to grab a beer, maybe they won’t pay for that thing on Amazon, then they won’t come back to pick it up and buy more chips and beers.

They may also turn to more pure-play eCommerce businesses like Rappi, a Latin American Super App that offers food delivery, groceries, and retail, Amazon, and Mercado Libre. They may set up a Mercado Pago digital wallet to pay for it all.

OXXO’s 20,000 location footprint, a major moat during normal times, is less impactful when people don’t leave the house as frequently, creating an opening for competitors who don’t want to pay a tax to FEMSA for every online transaction.

Still, as Lindsay Lehr points out, creating liquidity for digital wallets in Latin America is really hard, and OXXO Saldazo’s hybrid approach -- starting with the prepaid debit card, with physical touchpoints, backed by one of Mexico’s most trusted brands -- is the only one that has worked in the country to date.

Latin America will be one of the next decade’s biggest growth stories, and just as Asia and India have seen fierce competition to own customers’ digital lives, Latin America will be a knife fight. Whether FEMSA comes out on top will depend on whether it’s able to leverage its physical advantage before the market gets comfortable with digital-only solutions.

So What Will It Be?

Throughout FEMSA’s 130 year history, betting against the company, particularly when it looked like it was down and out, was never the right call. Now is no different.

In the worst case scenario, FEMSA, an undisputed market leader with an impossible-to-replicate physical network of trusted c-stores, is just a CPG business trading at the multiple of a structural loser.

The bull case for FEMSA is that it leverages its distribution advantage and consumer touch-points to launch the leading digital wallet in Mexico. The Mexican economy should directly benefit from more sanguine relations with a new administration in the U.S. and will continue to benefit from off-shoring of manufacturing from China to Mexico. As a potential key player the digitization and development of an increasingly important economic partner to the United States, FEMSA's strategic assets and distribution know-how position them to play a key role as the toll-keeper of Mexico’s eCommerce ecosystem.

FEMSA takes the long view. As a result, it has smartly and patiently put the right pieces in place over decades. It built bottling and distribution capabilities through its breweries that it parlayed into the world’s largest Coca-Cola bottler by volume and the largest c-store chain in The Americas by locations. It’s leveraged its physical footprint to engrain itself in its customers’ routines and build their trust, which it used to create the country’s most popular debit card and turn itself into the physical manifestation of the Mexican internet.

The company’s patience has given it the tools and opportunity to build the digital wallet and Super App for Mexico, and potentially much of Latin America. But they are in a tight window that COVID tightened, and now they need to move quickly to concentrate their resources on capturing the big, digital prize.

How do we think it’ll play out?

Never bet against the Devil. Viva FEMSA.

Thanks to Post Market for collaborating with me on this, and to Dan and Puja for editing.

Full Disclosure: I own a small amount (<2% of my portfolio) of FMX. This is not investment advice!

Thanks for reading, and Happy Thanksgiving!

Packy

FEMSA (Audio)